Caio Fabbricio (Handel)

| Work data | |

|---|---|

| Original title: | Caio Fabbricio |

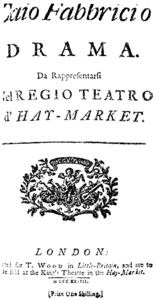

Title page of the libretto, London 1733 |

|

| Shape: | Opera seria |

| Original language: | Italian |

| Music: | Johann Adolph Hasse u. a., editing: Georg Friedrich Händel |

| Libretto : | Apostolo Zeno , Cajo Fabrizio (Vienna 1729) |

| Premiere: | December 4, 1733 |

| Place of premiere: | King's Theater , Haymarket, London |

| Place and time of the action: | Tarent , 279 BC Chr. |

| people | |

|

|

Caio Fabbricio , also Cajo Fabricio or Cajo Fabrizio ( HWV A 9 ) is a dramma per musica in three acts. The piece, based on Johann Adolph Hasse's opera of the same name, is an arrangement by Georg Friedrich Handel and the second pasticcio of three in the 1733/34 season at the London Theater am Haymarket .

Emergence

Less than a month after the last performance of the Orlando on May 5, 1733, the famous castrato Senesino left Handel's ensemble, after having been with a competing opera company that was being planned on June 15, 1733 and soon as an opera of the Nobility ("Adelsoper") became known, had negotiated a contract. Identical June 2 press releases from The Bee and The Craftsman state :

“We are credibly inform'd that one day last week Mr. H – d – l, Director-General of the Opera-House, sent a Message to Signior Senesino, the famous Italian Singer, acquainting Him that He had no earlier Occasion for his service; and that Senesino reply'd the next day by a letter, containing a full resignation of all his parts in the Opera, which He had performed for many years with great applause. "

“As we know from a reliable source, Mr. Handel, the general manager of the opera house, sent the famous Italian singer Signor Senesino a message last week informing him that he has no further use for his services; and that Senesino replied by letter the next day that he was giving up all of his roles in the opera, which he had played with great applause for many years. "

Senesino joined almost all of Handel's other singers: Antonio Montagnana , Francesca Bertolli and the Celestina . Only the soprano Anna Maria Strada del Pò remained loyal to Handel. After returning from Oxford from a successful series of concerts in July 1733, Handel wrote a new opera, Arianna in Creta , for the coming season and prepared three pasticci with music by the more “modern” composers Leonardo Vinci and Hasse , perhaps around the to beat rival aristocratic opera and their musical boss Porpora at their own arms.

Meanwhile, London was eagerly awaiting the new opera season, as Antoine-François Prévost d'Exiles, author of the famous novel Manon Lescaut , writes in his weekly Le Pour et le Contre (The pros and cons) :

«L'Hiver (c) approche. On scait déja que Senesino brouill're irréconciliablement avec M. Handel, a formé un schisme dans la Troupe, et qu'il a loué un Théâtre séparé pour lui et pour ses partisans. Les Adversaires ont fait venir les meilleures voix d'Italie; ils se flattent de se soûtenir malgré ses efforts et ceux de sa cabale. Jusqu'à présent ìes Seigneurs Anglois sont partagez. La victoire balancera longtems s'ils ont assez de constance pour l'être toûjours; mais on s'attend que les premiéres représentations décideront la quereile, parce que le meilleur des deux Théâtres ne manquera pas de reussir aussi-tôt tous les suffrages. »

"The winter is coming. The reader is already aware that there was a final break between Senesino and Handel, and that the former sparked a split in the troupe and leased his own theater for himself and his followers. His opponents got the best votes from Italy; they have enough pride to want to continue despite the machinations of Senesino and his clique. The English nobility is currently split into two camps; neither of the two parties will be victorious for a long time if they all stick to their point of view. But it is expected that the first performances will put an end to the dispute, because the better of the two theaters will inevitably attract everyone's support. "

Handel and Heidegger hastily put together a new troupe and a new repertoire. Margherita Durastanti , now a mezzo-soprano, over three decades earlier in Italy Handel's prima donna , in the early 1720s - before the great times of Francesca Cuzzoni and Faustina Bordoni - the mainstay of the Royal Academy of Music , returned from Italy, although she was her last appearance the season ended on March 17, 1724 with the sung lines of an English cantata:

"But let old Charmers yield to new, Happy Soil, adieu, adieu."

"But let the old wizards give way to the new one, good-bye, good-bye, lucky soil!"

Due to the almost complete change of his ensemble, Handel had very little time to prepare for the new season. Then there were the oratorios in Oxford, which kept him busy throughout July. It can be assumed that he had planned the new season earlier without suspecting that his singers would be terminated, because the five-year contract he had signed with Heidegger in 1729 was still running, albeit in his own last year. But now the new situation demanded that Handel had to produce more operas than he had done in recent years. This led to the unusual situation that three pasticci were produced at the Haymarket this season. After the Semiramide riconosciuta and the Caio Fabbricio , Arbace was to follow.

At the beginning of the season, Handel had his entire new line of singers. Two new castrati, Carlo Scalzi and Giovanni Carestini , had been hired, and so on October 30th, the birthday of King George (a day usually celebrated with a princely ball at St James's Palace ), Handel was able to give the pasticcio Semiramide open the season: two months before his competitors, although he had new singers, the aristocratic opera, on the other hand, his old troupe. It is possible that his original plan was to open the season with all of his seven singers in the Caio Fabbricio , but since the actor in the title character, Gustav Waltz , was temporarily unavailable (he had a parallel engagement at the Drury Lane Theater ), Handel probably had to reschedule. The adaptation of Hasse's opera had its premiere on December 4, 1733 in the King's Theater on Haymarket. Like Semiramide before , this pasticcio also failed and also only achieved four performances.

- Cast of the premiere

- Pirro - Giovanni Carestini , called "Il Cusanino" ( castrato mezzo- soprano )

- Sestia - Anna Maria Strada del Pó ( Soprano )

- Volusio - Carlo Scalzi , called "Il Cichione" (Soprano Castrato)

- Caio Fabbricio - Gustav Waltz ( bass )

- Bircenna - Margherita Durastanti (mezzo-soprano)

- Turio - Maria Caterina Negri ( Alto )

- Cinea - Maria Rosa Negri (mezzo-soprano)

The question arises as to why Handel brought so many operas by other composers onto the stage instead of his own. After the opening of the season with Semiramide there was a resumption of his Ottone (November 13th). According to Caio Fabbricio, however, his answer to Porporas Arianna in Nasso (on January 1, 1734 at the aristocratic opera) was not his own Arianna - although this had long been completed - but Vinci's Arbace on January 5. He deliberately wanted to oppose Porpora's new music and the current taste of the aristocratic opera, not his, but the modern, melody-dominated and less contrapuntal spelling of the "opposing" camp, and their most popular chants of recent years. But Handel's calculation does not seem to have worked out completely on this point, because only Arbace - under the original title Artaserse , it was soon the most popular opera material in Italy - had made a certain impression with eight performances. The hopes of being able to keep the competition in check with their own weapons were therefore disappointed. Handel's supporters were fixated on his compositions, while those whom he hoped to win with the music of the new Italians stayed away, not least out of loyalty to the competition.

libretto

The original text for the opera is Apostolo Zeno's "dramma per musica" Cajo Fabricio , first performed on November 4, 1729 in the Vienna Court Theater with music by Antonio Caldara . The text version reproduced in the libretto for this performance corresponds largely, but not in every detail, to the text of the Zeno work edition "Poesie drammatiche" from 1744. Hasse's opera, premiered on January 12, 1732 in Rome, the basis for Handel's version, was after Only the second setting of this text is evidence of the preserved libretti. A comparison of the libretto for Hasse's opera with the libretto of the first setting, which was performed just over two years earlier, shows unusually extensive deviations; The author of these changes was the Roman poet Niccolò Coluzzi , who received a fee of 30 scudi for this . As usual, Coluzzi deleted individual recitative passages up to an entire scene in many scenes; the deleted verses are partly printed in the usual Virgolette in the Roman textbook , partly omitted entirely. In addition, he changed the wording of numerous verses. The spectrum ranges from the selective exchange of individual words to the substantial revision and rewrite of longer passages, and in part also concerns sections that were not set to music by Hasse and are marked accordingly in the libretto. In addition, Volusio at the end of the second act and Cajo Fabricio in the third act each received an additional solo scene. After all, most of the aria texts have been exchanged. The choir and ball scene that opened the second act was also completely rewritten; However, Hasse only set the first two verses of the new, rather extensive text to music, while the remaining verses in the libretto are provided with Virgolette. Overall, this text processing differs significantly in quality from the usual way in Italy of setting up older text books for new settings and performances. It should be borne in mind, of course, that the model is a poem by Zenos, whose vocabulary may have seemed a bit antiquated even then, so that Coluzzi may find a more thorough treatment and "modernization" desirable. Zeno's model was later set to music by Pietro Antonio Auletta (Turin 1743), Paolo Scalabrini (Graz 1743), Carl Heinrich Graun (Berlin 1746) and Gian Francesco de Majo (Livorno 1760), among others . Another episode in Pyrrhus' life deals with his libretto Pirro , which was set to music by Giuseppe Aldrovandini (Venice 1704) and Francesco Gasparini (Rome 1717).

action

Historical and literary background

The historical framework for the largely invented plot of the opera goes back to the Rômaïkề Archaiología (19th book, chapter 13) of Dionysius of Halicarnassus , the biography of Pyrrhus in Plutarch's Bíoi parálleloi (Parallel Descriptions of Life), the 9th book of Ab Urbe Condita of Titus Livius and the Historia Romana (9th book, fragment 39) by Cassius Dio .

Lower Italy was in the third century BC. Populated with numerous Greek villages and cities ( Magna Graecia ) and thus a sphere of interest for the Greeks . After Rome had consolidated its rule in central Italy, it tried to expand its influence in southern Italy. When Rome came to the aid of the Thurii , Locri and Rhegium settlements , they violated Taranto's sphere of interest . In 282 BC There was an attack on the Roman fleet in the port of Taranto (which according to a treaty of 303 BC it was actually not allowed to call), which triggered the Pyrrhic War . Taranto then called upon King Pyrrhus of Epirus for help, who saw an opportunity to expand his kingdom. Pyrrhus landed with 20,000 mercenaries, 3,000 Thessalian riders and 26 war elephants in southern Italy and took over the supreme command. After the Romans 280 BC. After having been defeated at Herakleia in the 3rd century BC , Gaius Fabricius Luscinus was the leader of the Roman legation that negotiated with the king. He refused the peace conditions of Pyrrhus and probably also the ransom and the exchange of prisoners. Plutarch reports that Pyrrhus was so impressed that he could not bribe Fabricius that he even released the prisoners without a ransom. The war that took place between 280 and 275 BC Raged, was a significant harbinger of the Punic Wars , as Rome established itself as a major military power through its eventual victory, and thus inevitably headed for a confrontation with the other great power in the Mediterranean, Carthage ( Pyrrhic War ).

The later Roman historians praised Fabricius as a virtuous figure of light of ancient Roman moral rigor and decorated his biography accordingly. His diplomatic activities around King Pyrrhos and the negotiations initiated by Cienas after the battle of Asculum (279 BC) were particularly emphasized . The episode in which a traitor wanted to poison the foreign king, but Fabricius sent him back with a warning, was highlighted as particularly indicative of his righteousness, incorruptibility and his fearless audacity. His counterpart Pyrrhus was generally regarded as a highly talented general and strategist. However, his victories against the Roman troops were associated with high losses (hence the term Pyrrhic victory ), in the end he had to ask the defeated for peace. This request was rejected by the Roman Senate. In the battle of Beneventum , 275 BC. The tide turned and the Greeks suffered a decisive defeat that caused Pyrrhus to leave Italy and return to Epirus.

Rome looked back with pride on the generally successful defensive battle against Pyrrhus. Pyrrhus was not denigrated by the Roman historians , like many other opponents of Rome, while the Greek world became aware of the new power of Rome through this event.

content

Pirro, King of Epirus, is the leader of the Tarentines and other Italian Greeks in their war against Rome. After a great Greek victory, Rome sends the esteemed statesman Caio Fabbricio to negotiate with Pirro. Among the Roman prisoners is Fabbricio's daughter Sestia, with whom Pirro falls in love. After an unsuccessful attempt to bribe Fabbricio with treasures, Pirro suggests that he could marry Sestia, which the latter indignantly refuses. In this situation, Fabbricio sees suicide as the only way out for his daughter and so he slips her a dagger. When Sestia wants to commit suicide in a hopeless situation, her beloved Volusio, who is believed to be dead, saves her from death. He now wants to kill the tyrant, but out of jealousy (i.e. a sensual affect), not for moral reasons. Therefore Sestia refuses him the act. Pirro's fiancée Bircenna, disguised as "Glaucilla", allies herself with Turio, a Tarentine who hates Pirro for his disturbances of customs and traditions in Taranto. Turio makes Fabbricio the offer that he can betray Pirro after all; Fabbricio would like to have this offer in writing. Volusio is exposed when he intervenes in an assassination attempt ordered by Bircenna and Turio and in this way even saves the tyrant's life. Turio helps Sestia and Volusio escape, but Fabbricio brings them back to Pirro and Volusio is captured again. On Pirro's orders, Fabbricio now has to pass judgment on Volusio. After learning that Volusio wanted to kill the tyrant out of jealousy and not for moral reasons, he passes the death sentence on his potential son-in-law who is guided by blind affect. Everything seems lost until Fabbricio gives Pirro the letter, which reveals his betrayal and murder plan. Pirro is impressed by so much Roman virtue and pardons everyone. He releases Sestia and Volusio, as well as the other Roman prisoners, and there are even indications of a future reconciliation with Bircenna.

Argomento

'Pirrus, King of Macedonia and Epirus, was called to aid by the Tarentines and other Italian peoples who were waging war against the Romans, and fought the Romans a bloody battle in which he was victorious with difficulty. He himself would have been killed in the same by a brave Roman knight (who was called Volusius), if he did not use caution, one of his friends, the Megacles, with the royal. To clothe coat, which was slain in his place by Volusius. After the battle he had the famous speaker Cineas offer peace to the Romans, who however stubbornly refused it. Soon after his return to the Pirrus, the Cienas was followed by the Roman ambassadors, whose head was Cajus Fabricius, a famous Roman councilor who, although he had gone through all the levels of honorary positions, was nevertheless in the extreme poverty. Pirrus tried to win him over by offering great treasures, but in vain; Rather, the virtue of this man compelled the king to accept the peace that the Romans wanted it to be. All of this is based on history. Everything else that is used to involve the drama is an invention.

The scene is in front of the Apulian stand Taranto in Italy.

The time is the day when the Saturnial Festival was held.

The play originally comes from the famous Mr. Apostolo Zeno. "

Plot structure

The main plot of the opera is developed from the opposing characters of two characters: On the one hand, there is the decadent tyrant Pirro, who wages war against the Romans on behalf of the Republic of Taranto, which has also sunk into decadence. Roman virtue, on the other hand, is embodied in Caio Fabbricio. These two figures create a value opposition between tyranny and freedom or between sensuality (love) and virtue. A superficial examination could give the impression that the love theme, for which Zeno is also drafting a subplot, in which Turio, the head of Taranto, falls in love with Bircenna, Pirro's bride, and not the opposition virtue - sensuality is the center of the opera form. Zeno's libretto would thus correspond to the classic Venetian scheme of a double triangular constellation. Although this constellation can actually be identified (Pirro - Sestia - Volusio / Pirro - Bircenna - Turio), love is introduced in these figure constellations not as a dramatic end in itself, but as a passion to be overcome. Turio overcomes his love for Bircenna, he prefers fame. Through his love for Sestia, Volusio must recognize that it is not passions but reasonable virtue that should be the guideline for action. Nonetheless, Caio Fabbricio remains arrested by the implied double triangular constellation of traditional Venetian opera. The tyrant's sudden mildness at the end of the opera, which offends his character and is a clear concession to the lieto-fine aesthetic of Italian opera, remains questionable.

music

Handel's score is based on a manuscript which he had recently acquired from his friend and later librettist Charles Jennens . This manuscript, now in the Newberry Library in Chicago , contains all twenty-eight of Hasse's arias (noting that Volusio's aria is Nocchier che teme assorto , No. 14, by Porpora), but it lacks the overture, two choirs, and the recitatives.

Handel's pencil notes in this score give indications of his rearrangements and strokes. In essence, he kept the music from Hasse's original score, which only had to be transposed and arranged according to the requirements of his ensemble, which is not always correctly recorded in the director's score due to lack of time. At first Handel probably wanted to use most of the Hasse arias, but in the end only thirteen remained, while seven arias by Tommaso Albinoni , Francesco Corselli , Hasse, Leonardo Leo and Leonardo Vinci were recorded at the request of the singers . Carestini sang two arias that Vinci had composed for Caffarelli and, as in Semiramide , he also got a “Last Song” in Caio Fabbrico ( Vorrei da lacci scioglere , No. 21, by Leo). In return, three Pirro arias by Hate fell victim to the red pen. The title role, originally sung by the castrato Domenico Annibali , was cut to a single aria by Handel for the bassist Waltz, who was not so outstanding in his voice. A planned second aria had to be omitted because it had previously been inserted into Semiramide . Already at an early stage, the assignment of the roles of Bircenna and Turio to Margherita Durastanti and Maria Caterina Negri was reversed after the Durastanti had probably contradicted the dramatically less important role of Turio. Nevertheless, her new role was shortened to only three arias, while the Negri was reduced to two. Almost all of the recitatives were set to music by Handel and entered into the director's score by hand. As in Semiramide , these are exceptionally well done and contain many skillful dramatic moments. The overture (“Sinfonia”), which is only handed down as a basso part in the director's score, comes from an unknown model and has not yet been identified (like the final chorus); it was added to the score afterwards.

The fundamental difference to Semiramide in terms of the procedure is that Handel took a third of the arias from other operas from the outset, whereas in Caio Fabbricio he did not intend to do so and was only forced to do so later when roles and special requests were made by the singers.

Handel and the pasticcio

The pasticcio was a source for Handel, of which he made frequent use at this time, as the competitive situation with the aristocratic opera put him under pressure. They were nothing new in London or on the continent, but Handel had only released one in previous years, L'Elpidia, ovvero Li rivali generosi in 1724. Now he delivered seven more within five years: Ormisda in 1729/30, Venceslao 1730/31, Lucio Papirio dittatore in 1731/32, Catone 1732/33, and now no less than three, Semiramide riconosciuta , Caio Fabbricio and Arbace in 1733/34. Handel's working method in the construction of the pasticci was very different, but all materials are based on libretti by Zeno or Metastasio , which are familiar in the European opera metropolises and which many contemporary composers had adopted - above all Leonardo Vinci , Johann Adolph Hasse , Nicola Porpora , Leonardo Leo , Giuseppe Orlandini and Geminiano Giacomelli . Handel composed the recitatives or adapted existing ones from the chosen template. Very rarely did he rewrite an aria, usually in order to adapt it to a different pitch and tessit . Wherever possible, he included the repertoire of the singer in question in the selection of arias. Most of the time the arias had to be transposed when they were transferred from one context to another or transferred from one singer to another. They also got a new text by means of the parody process . The result didn't always have to make sense, because it was more about letting the singers shine than producing a coherent drama. Aside from Ormisda and Elpidia , who were the only ones to see revivals , Handel's pasticci weren't particularly successful - Venceslao and Lucio Papirio dittatore only had four performances each - but like revivals, they required less work than composing and rehearsing new works could well be used as a stopgap or start of the season, or step in when a new opera, as was the case with Partenope in February 1730 and Ezio in January 1732, was a failure. Handel pasticci have one important common feature: the sources were all contemporary and popular materials that had been set to music in the recent past by many composers who set in the “modern” Neapolitan style. He had introduced this with the Elpidia of Vinci in London and later this style merged with his own contrapuntal working method to the unique mixture that permeates his later operas.

orchestra

Two oboes , two horns , strings, basso continuo ( violoncello , lute , harpsichord ).

literature

- Bernd Baselt : Thematic-systematic directory. Instrumental music, pasticci and fragments. In: Walter Eisen (Ed.): Handel manual: Volume 3 , Deutscher Verlag für Musik , Leipzig 1986, ISBN 3-7618-0716-3 , p. 381 f.

- Reinhard Strohm : Handel's pasticci. In: Essays on Handel and Italian Opera , Cambridge University Press 1985, Reprint 2008, ISBN 978-0-521-26428-0 , pp. 183 ff. (English).

- Winton Dean : Handel's Operas, 1726-1741. Boydell & Brewer, London 2006. Reprint: The Boydell Press, Woodbridge 2009, ISBN 978-1-84383-268-3 , pp. 128 ff. (English).

- John H. Roberts: Caio Fabbricio. In: Annette Landgraf and David Vickers: The Cambridge Handel Encyclopedia , Cambridge University Press 2009, ISBN 978-0-521-88192-0 , p. 113 f. (English).

- Apostolo Zeno : Caio Fabbricio drama. Da rappresentarsi nel Regio Teatro d'Hay-Market. Reprint of the 1733 libretto, Gale Ecco, Print Editions, Hampshire 2010, ISBN 978-1-170-15632-2 .

- Steffen Voss : Pasticci: Caio Fabbricio. In: Hans Joachim Marx (Hrsg.): The Handel Handbook in 6 volumes: The Handel Lexicon. (Volume 6), Laaber-Verlag, Laaber 2011, ISBN 978-3-89007-552-5 , pp. 559 f.

Web links

- further information on Caio Fabbricio. (haendel.it)

- further information on Caio Fabbricio. (gfhandel.org)

Individual evidence

- ^ Editing management of the Halle Handel Edition: Documents on life and work. In: Walter Eisen (Ed.): Handel Handbook: Volume 4. Deutscher Verlag für Musik, Leipzig 1985, ISBN 3-7618-0717-1 , p. 208.

- ↑ David Vickers: Handel. Arianna in Creta. Translated from the English by Eva Pottharst. MDG 609 1273-2, Detmold 2005, p. 30.

- ↑ Winton Dean : Handel's Operas, 1726-1741. Boydell & Brewer, London 2006. Reprint: The Boydell Press, Woodbridge 2009, ISBN 978-1-84383-268-3 , p. 133.

- ^ Editing management of the Halle Handel Edition: Documents on life and work. In: Walter Eisen (Hrsg.): Handel manual: Volume 4. Deutscher Verlag für Musik, Leipzig 1985, ISBN 3-7618-0717-1 , p. 225.

- ↑ a b c Christopher Hogwood: Georg Friedrich Handel. A biography (= Insel-Taschenbuch 2655). Translated from the English by Bettina Obrecht. Insel Verlag, Frankfurt am Main / Leipzig 2000, ISBN 3-458-34355-5 , p. 202 ff.

- ↑ Commerce Reference Database. ichriss.ccarh.org, accessed February 7, 2013 .

- ↑ a b c Reinhard Strohm : Handel's pasticci. In: Essays on Handel and Italian Opera , Cambridge University Press 1985, Reprint 2008, ISBN 978-0-521-26428-0 , pp. 183 ff. (English).

- ^ Roland Dieter Schmidt-Hensel: La musica è del Signor Hasse detto il Sassone ... , Treatises on the history of music 19.2. V&R unipress, Göttingen 2009, ISBN 978-3-89971-442-5 , p. 222 f.

- ^ Dionysius of Halicarnassus (English) .

- ↑ Plutarch (English by John Dryden )

- ^ Pyrrhus in Titus Livius (English).

- ^ A b John H. Roberts: Caio Fabbricio. In: Annette Landgraf and David Vickers: The Cambridge Handel Encyclopedia , Cambridge University Press 2009, ISBN 978-0-521-88192-0 , p. 113 f. (English)

- ↑ a b Bernhard Jahn: The senses and the opera: sensuality and the problem of their verbalization. Max Niemeyer Verlag GmbH, Tübingen 2005, ISBN 3-484-66045-7 , p. 225 f.

- ^ Cajo Fabricio: Dramma per musica. digital.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de, accessed on September 3, 2013 .

- ^ Bernd Baselt : Thematic-systematic directory. Instrumental music, pasticci and fragments. In: Walter Eisen (Ed.): Händel-Handbuch: Volume 3 , Deutscher Verlag für Musik , Leipzig 1986, ISBN 3-7618-0716-3 , p. 381.

- ↑ Winton Dean : Handel's Operas, 1726-1741. Boydell & Brewer, London 2006. Reprint: The Boydell Press, Woodbridge 2009, ISBN 978-1-84383-268-3 , pp. 128 f.