Arbace

| Work data | |

|---|---|

| Original title: | Arbace |

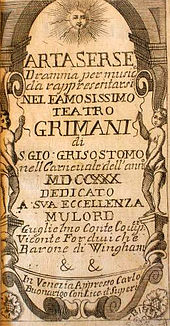

Title page of the libretto, London 1733 |

|

| Shape: | Opera seria |

| Original language: | Italian |

| Music: | Leonardo Vinci , Johann Adolph Hasse a . a., editing: Georg Friedrich Händel |

| Libretto : | Pietro Metastasio , Artaserse (Rome 1730) |

| Premiere: | January 4, 1734 |

| Place of premiere: | King's Theater , Haymarket, London |

| Place and time of the action: | Susa , 465 BC Chr. |

| people | |

|

|

Arbace ( HWV A 10 ) is a dramma per musica in three acts. The pasticcio is the arrangement of the successful libretto Artaserse by Pietro Metastasio , based on the opera Leonardo Vinci , by Georg Friedrich Händel . In the 1733/34 season it was the third pasticcio at the Royal Theater on Haymarket in London.

Emergence

Less than a month after the last performance of the Orlando on May 5, 1733, the famous castrato Senesino left Handel's ensemble, after having worked with a competing opera company that was being planned on June 15, 1733 and soon as an opera of the Nobility ("Adelsoper") should become known, had negotiated a contract. Identical June 2 press releases from The Bee and The Craftsman state :

“We are credibly inform'd that one day last week Mr. H – d – l, Director-General of the Opera-House, sent a Message to Signior Senesino, the famous Italian Singer, acquainting Him that He had no earlier Occasion for his service; and that Senesino reply'd the next day by a letter, containing a full resignation of all his parts in the Opera, which He had performed for many years with great applause. "

“As we know from a reliable source, Mr. Handel, the general manager of the opera house, sent the famous Italian singer Signor Senesino a message last week informing him that he has no further use for his services; and that Senesino replied by letter the next day that he was giving up all of his roles in the opera, which he had played with great applause for many years. "

Senesino joined almost all of Handel's other singers: Antonio Montagnana , Francesca Bertolli and the Celestina . Only the soprano Anna Maria Strada del Pò remained loyal to Handel. After returning from Oxford from a successful series of concerts in July 1733, Handel wrote a new opera, Arianna in Creta , for the coming season. and prepared three pasticci with music by the “more modern” composers Leonardo Vinci and Hasse , perhaps to defeat the rival aristocratic opera and its musical director Nicola Porpora at their own guns.

Meanwhile, London was eagerly awaiting the new opera season, as Antoine-François Prévost d'Exiles, author of the famous novel Manon Lescaut , writes in his weekly Le Pour et le Contre (The pros and cons) :

«L'Hiver (c) approche. On scait déja que Senesino brouill're irréconciliablement avec M. Handel, a formé un schisme dans la Troupe, et qu'il a loué un Théâtre séparé pour lui et pour ses partisans. Les Adversaires ont fait venir les meilleures voix d'Italie; ils se flattent de se soûtenir malgré ses efforts et ceux de sa cabale. Jusqu'à présent ìes Seigneurs Anglois sont partagez. La victoire balancera longtems s'ils ont assez de constance pour l'être toûjours; mais on s'attend que les premiéres représentations décideront la quereile, parce que le meilleur des deux Théâtres ne manquera pas de reussir aussi-tôt tous les suffrages. »

"The winter is coming. The reader is already aware that there was a final break between Senesino and Handel, and that the former sparked a split in the troupe and leased his own theater for himself and his followers. His opponents got the best votes from Italy; they have enough pride to want to continue despite the machinations of Senesino and his clique. The English nobility is currently split into two camps; neither of the two parties will be victorious for a long time if they all stick to their point of view. But it is expected that the first performances will put an end to the dispute, because the better of the two theaters will inevitably attract everyone's support. "

Handel and Heidegger hastily put together a new troupe and a new repertoire. Margherita Durastanti , now a mezzo-soprano, over three decades earlier in Italy Handel's prima donna , in the early 1720s - before the great times of Francesca Cuzzoni and Faustina Bordoni - the mainstay of the Royal Academy of Music , returned from Italy, although she was her last appearance the season ended on March 17, 1724 with the sung lines of an English cantata:

"But let old Charmers yield to new, Happy Soil, adieu, adieu."

"But let the old wizards give way to the new one, good-bye, good-bye, lucky soil!"

Due to the almost complete change of his ensemble, Handel had very little time to prepare for the new season. Then there were the oratorios in Oxford, which kept him busy throughout July. It can be assumed that he had planned the new season earlier without suspecting that his singers would be terminated, because the five-year contract he had signed with Heidegger in 1729 was still running, albeit in his own last year. But now the new situation demanded that Handel had to produce more operas than he had done in recent years. This led to the unusual situation that three pasticci were produced at the Haymarket this season. After the Semiramide riconosciuta and the Caio Fabbricio , Arbace followed .

At the beginning of the season, Handel had his entire new line of singers. Two new castrati, Carlo Scalzi and Giovanni Carestini , had been hired, and so on October 30th, the birthday of King George (a day usually celebrated with a princely ball at St James's Palace ), Handel was able to give the pasticcio Semiramide open the season: two months before his competitors, although he had new singers, the aristocratic opera, on the other hand, his old troupe. Then there was a resumption of his Ottone (November 13th) and the adaptation of an opera by Johann Adolph Hasse , Caio Fabbricio (December 4th 1733). However, his answer to the premiere of Porporas Arianna in Nasso on January 1, 1734 at the competing aristocratic opera was not his own Arianna - although it was long overdue - but Arbace - under the original title Artaserse, the most popular opera material in Italy. The choice of the piece was certainly related to the fact that the part of Arbace in Vinci's successful opera had been composed for Carestini, so that the singer was able to build on his great success here: in order to satisfy the hierarchy of roles, Handel probably changed it also the title and named it after the role of its first protagonist. But he had an even more far-reaching strategy: he consciously did not want Porpora's new music and the current taste of aristocratic opera, but rather the modern, melody-dominated and less contrapuntal spelling of the "opposing" camp, as well as their most popular chants of recent years, oppose. That is why he had already brought two pasticci on stage in the current season, but they only had a few performances. So if this calculation didn't work out well at first, Arbace had made a certain impression with at least nine performances (six evenings in January and three more in March). John Walsh edited a small collection of arias, The Favorite Songs in the Opera call'd Arbaces . Overall, however, the hope of being able to keep the competition in check with their own weapons was disappointed. Handel's supporters were fixated on his compositions, while those whom he hoped to win with the music of the new Italians stayed away, not least out of loyalty to the competition.

- Cast of the premiere

- Arbace - Giovanni Carestini , called "Il Cusanino" ( castrated mezzo- soprano )

- Mandane - Anna Maria Strada del Pó ( Soprano )

- Artaserse - Carlo Scalzi , called "Il Cichione" (Soprano Castrato)

- Artabano - Margherita Durastanti (mezzo-soprano)

- Semira - Maria Caterina Negri ( Alto )

- Megabise - Maria Rosa Negri (mezzo-soprano)

Six months later, the Opera of the Nobility responded with a pasticcio arrangement of Johann Adolph Hasse's Artaserse , the second famous setting of the Metastasio text, and achieved an extraordinary success. The famous castrato Farinelli (who never sang under Handel) achieved his breakthrough in London and sang one of his most famous arias here: Son qual nave ch'agitata .

libretto

The text for the opera is Pietro Metastasio's successful poem, his "dramma per musica" Artaserse , performed for the first time during the carnival season on February 4, 1730 in the Teatro delle Dame in Rome with the music of Leonardo Vinci, his last opera before his mysterious death. Just seven days later, Hasse's Artaserse premiered in Venice . It was - as in the case of Ezio (1728/29) and Semiramide (1729) - a "double premiere" of Metastasius' latest poetry in Rome and Venice, the text of which the poet himself copied well before the "official" Roman premiere Venice must have sent, for which he - according to the “Bilanzo” of the 1729/30 season of the Teatro San Giovanni Grisostomo - received the respectable sum of £ 3,300.

In Artaserse is one of the most popular opera materials of the 18th century and one of the meistvertonten Libretti: There are more than 90 known musical settings. After Vinci and Hasse, there are Giuseppe Antonio Paganelli (Braunschweig 1737), Giovanni Battista Ferrandini (Munich 1739), Christoph Willibald Gluck (Milan 1741), Pietro Chiarini (Verona 1741), Carl Heinrich Graun (Berlin 1743), Giuseppe Scarlatti (Lucca 1747 ), Baldassare Galuppi (Vienna 1749), Johann Christian Bach (London 1760), Josef Mysliveček (Naples 1774) and Marcos António Portugal (Lisbon 1806). The original libretto was often edited and also translated into other languages: Thomas Arne composed his Artaxerxes in English in 1762. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart's aria for soprano and orchestra Conservati fedele (KV 23, 1765) is a setting of the farewell verses by Artaserse's sister Mandane at the end of the first scene.

action

Historical and literary background

The plot refers to the historical figure of the Persian great king Artaxerxes I in the 5th century BC. Chr., The son of Xerxes I and Amestris , which according to the transmission of Diodorus ( Diodori Siculi Bibliotheca Historica , 11 Book, 71, 2) after the assassination of his father in a palace coup, this under not completely clarified circumstances young succeeded on the throne. Plutarch, in turn, reports on Artaxerxes in his Bíoi parálleloi (Parallel Descriptions of Life) and emphasizes the gentleness and nobility of the Persians ( Artaxerxes 4, 4). In Themistocles (27-29), Plutarch provides evidence of the noble disposition and political foresight of Artaxerxes, as he honored his father's opponent, Themistocles, who had to flee Greece. Even Strabo treated the Great King in his Geographica under the name of Eratosthenes (the first book, Chapters 3, 4). Nepos praises his beauty and describes him as a strong and brave warrior ( De Regibus Exterarum Gentium 1, 4), Diodorus also emphasizes the efficient, but nevertheless mild reign of Artaxerxes I, who is said to have been in high regard among the Persians. In fact, during his long reign he has proven himself to be a capable and energetic king who, despite his youth, consolidated the Persian world power position when he came to power. The reputation of this king is quite positive in Greek tradition.

content

Artabano confesses to his son Arbace, Serse, who killed the king of the Persians. His son and heir to the throne Artaserse is said to be overthrown in order to bring Arbace to power. Arbace, who was banished by Serse because of his love for Mandane, Artaserse's sister, does not want to support his father's intrigues, as he has been friends with Artaserse since early childhood. Artaserse has his brother Dario killed as a parricide, but this soon turns out to be a misunderstanding and Arbace comes under suspicion. To protect his father Artabano, Arbace doesn't defend himself against the allegations. Artaserse appoints Artabano to be the judge over his son and the latter sentences him to death. Artaserse, who himself is not convinced of Arbace's guilt, helps him to escape. Artabano, together with his ally Megabise, prepares the people for a coup and prepares a poisoned drink for Artaserse to kill him. But Arbace can prevent the coup. Artaserse, now convinced of Arbace's innocence, hands him the (poisoned) potion as an oath. Artabano intervenes, saying he couldn't bear to see his son poisoned - and admits his guilt: he is the murderer of Serse and the traitor. Artaserse has him sentenced to death, but Arbace begs for mercy for him. Artabano is sent into exile and Arbace receives mandane as his wife, while Artaserse marries Arbace's sister Semira. Righteousness and goodness prevail.

Argomento

“When the power of the Persian monarch Xerxes, after various defeats which he had suffered from the Greeks, decreased more and more every day; so an ambitious confidante of the same, the colonel of his bodyguard, Artabanus, was tempted to swing himself on the Persian throne in the place of his master, and at this end to get him out of the way, along with the rest of the royal family. To do this he needed the privilege of his post, directly to be the king, once went into Xerxes' bedroom at night and killed him. Now he incited the two princes he had left behind against each other, aroused in the oldest, Artaxerxes, the suspicion that the younger, Darius, was to blame for the murder of their father, and he knew how to go so far that Artaxerxes had Darius killed . Now the faithless lacked nothing more than to get the Artaxerxes out of the world in order to achieve his goals completely. He had already taken all steps to do so, the execution of which were first halted by certain incidents (which are used for intermediate acts in the present drama), but finally even reversed when the betrayal came out, and Artaxerxes made sure of it. This discovery and the rescue of Artaxerxes is the main subject of current drama.

The setting is in Susa, the residence of the Persian monarchs.

The poetry of Abbot Metastasio. "

music

To set up his pasticcio, Handel used a manuscript that he had recently acquired (together with the collection of arias for Caio Fabbricio ) from his friend and later librettist Charles Jennens . This manuscript, now in the Sibley Music Library at the University of Rochester (USA), is a complete score of Vinci's opera. Handel's pencil notes in this score give indications of his rearrangements and strokes. If one studies this and the final director's score, one comes to the conclusion that it was probably his original plan to change as little as possible in the Vinci opera. For the first five scenes, he had the recitatives (in a shortened and slightly reworked form) from Smith sen. copy from the Jennens score, but already in the third scene the copyist began to leave some passages blank, as he had already done in the hand copy of Lucio Papirio dittatore . The role of Artabano, for example, which was initially to be occupied by bassist Gustav Waltz , was then taken on by Margherita Durastanti as the trouser role. Therefore her recitatives and her first aria are still notated in the bass clef and have not been rewritten for reasons of time. Only then does the part appear in the director's score according to the actual scoring in the mezzo-soprano. The same applies to the exchange of the role of Semira between Durastanti (mezzo-soprano, initially notated in the soprano clef, including Aria No. 4) and Maria Caterina Negri (alto, later recitatives notated in the alto clef), whose role of Megabise was finally given by her sister Maria Rosa Negri was acquired. After changing the line-up, which apparently emerged at the time Smith was copying the sixth scene, Handel wrote all the recitative notes by himself, while Smith had previously only transcribed the text. He also took over many of Vinci's passages unchanged, so that it is very difficult to tell the two composers apart in the director's score.

Schmidt must have started copying into the director's score as early as October 1733, before Waltz left, who had entered into a double engagement and also appeared in a piece by Johann Friedrich Lampe at the Drury Lane Theater . (This also necessitated changes to the score of the Semiramide , which premiered on October 30th.) The final version then contained four arias by Hasse and two by Giovanni Porta . Fourteen arias, an arioso , a duet, the final chorus and three accompaniment recitatives remained of Vinci's score . Carestini had sung the arbace in Vinci's opera in Rome, but since his voice had dropped a bit , Handel had to replace his aria Mi scacci sdegnato with another and delete the second half of the Arioso Perchè tarda (No. 19). But Carestini got, as in Semiramide and Caio Fabbricio , a “last song”. At first he wanted to sing Son qual nave che agitata (No. 9b), an aria of unknown origin (not to be confused with the aria by Hasse performed by Farinelli in Lucca and London at the competition), but later it became Di te degno non sarai (No. 26b) was replaced by Giovanni Porta and Son qual nave was moved to the end of the first act, where it replaced the famous Vo solcando un mar crudele (No. 9a) by Vinci. Similar to Scalzi, who wanted to exchange his aria in the third act, Nuvoletta opposta al sole , which was too high for him, with an aria by Hasse ( Potessi al mio diletto , No. 17, from Dalisa , 1730). But the pages that had been left blank in the score were then replaced by another, Se l'amor tuo mi rendi (also Hasse, No. 20, from Siroe , 1733) and the Dalisa arie moved to the second Act. Since Handel had already used Vinci's Sinfonia ( overture ) as an introduction to Semiramide riconosciuto , he chose the Sinfonia to Alessandro Scarlatti's Hirtenspiel II pastore di Corinto (Naples 1701) as a replacement , contrary to his custom when composing the pasticci, a very old-fashioned piece .

Handel and the pasticcio

The pasticcio was a source for Handel, of which he made frequent use at this time, as the competitive situation with the aristocratic opera put him under pressure. They were nothing new in London or on the continent, but Handel had only released one in previous years, L'Elpidia, ovvero Li rivali generosi in 1724. Now he delivered seven more within five years: Ormisda in 1729/30, Venceslao 1730/31, Lucio Papirio dittatore in 1731/32, Catone 1732/33, and now no less than three, Semiramide riconosciuta , Caio Fabbricio and Arbace in 1733/34. Handel's working method in the construction of the pasticci was very different, but all materials are based on libretti by Zeno or Metastasio , which are familiar in the European opera metropolises and which many contemporary composers had adopted - above all Leonardo Vinci , Johann Adolph Hasse , Nicola Porpora , Leonardo Leo , Giuseppe Orlandini and Geminiano Giacomelli . Handel composed the recitatives or adapted existing ones from the chosen template. Very rarely did he rewrite an aria, usually in order to adapt it to a different pitch and tessit . Wherever possible, he included the repertoire of the singer in question in the selection of arias. Most of the time the arias had to be transposed when they were transferred from one context to another or transferred from one singer to another. They also got a new text by means of the parody process . The result didn't always have to make sense, because it was more about letting the singers shine than producing a coherent drama. Aside from Ormisda and Elpidia , which were the only ones to see revivals , Handel's pasticci weren't particularly successful, but like the revivals, they required less work than composing and rehearsing new works and could well be used as stopgaps or the start of the season or step in when a new opera, as was the case with Partenope in February 1730 and Ezio in January 1732, was a failure. Handel pasticci have one important common feature: the sources were all contemporary and popular materials that had been set to music in the recent past by many composers who set in the “modern” Neapolitan style. He had introduced this with the Elpidia of Vinci in London and later this style merged with his own contrapuntal working method to the unique mixture that permeates his later operas.

Success and criticism

Handel's Brook Street neighbor and lifelong admirer Mrs. Pendarves (formerly Mary Granville) was a regular correspondent for the news of London musical life to her sister and she wrote:

“I went with Lady Chesterfield in her box. [...] 'Twas Arbaces, an opera of Vinci's, pretty enough, but not to compare to Handel's compositions. "

“I accompanied Lady Chesterfield to her box. [...] There was Arbaces , an opera by Vinci, very nice, but not to be compared with Handel's compositions. "

orchestra

Two oboes , bassoon , two horns , trumpet , strings, basso continuo ( violoncello , lute , harpsichord ).

literature

- Reinhard Strohm : Handel's pasticci. In: Essays on Handel and Italian Opera. Cambridge University Press 1985, Reprint 2008, ISBN 978-0-521-26428-0 , pp. 183 ff. (English).

- Bernd Baselt : Thematic-systematic directory. Instrumental music, pasticci and fragments. In: Walter Eisen (Ed.): Handel manual: Volume 3 , Deutscher Verlag für Musik , Leipzig 1986, ISBN 3-7618-0716-3 , p. 385 f.

- John H. Roberts: Arbace. In: Annette Landgraf and David Vickers: The Cambridge Handel Encyclopedia , Cambridge University Press 2009, ISBN 978-0-521-88192-0 , pp. 47 f. (English).

- Winton Dean : Handel's Operas, 1726-1741. Boydell & Brewer, London 2006. Reprint: The Boydell Press, Woodbridge 2009, ISBN 978-1-84383-268-3 , pp. 128 ff. (English).

- Pietro Metastasio : Arbace. Drama. Da rappresentarsi nel Regio Teatro d'Hay-Market. Reprint of the 1734 libretto, Gale Ecco, Print Editions, Hampshire 2010, ISBN 978-1-170-92403-7 .

- Steffen Voss: Pasticci: Arbace. In: Hans Joachim Marx (Hrsg.): The Handel Handbook in 6 volumes: The Handel Lexicon. (Volume 6), Laaber-Verlag, Laaber 2011, ISBN 978-3-89007-552-5 , p. 560.

Web links

- further information on Arbace. (haendel.it)

- further information on Arbace. (gfhandel.org)

- Original libretto by Metastasios Artaserse (Italian; PDF; 222 kB)

Individual evidence

- ^ Editing management of the Halle Handel Edition: Documents on life and work. In: Walter Eisen (Ed.): Handel Handbook: Volume 4. Deutscher Verlag für Musik, Leipzig 1985, ISBN 3-7618-0717-1 , p. 208.

- ↑ David Vickers: Handel. Arianna in Creta. Translated from the English by Eva Pottharst. MDG 609 1273-2, Detmold 2005, p. 30.

- ↑ Winton Dean : Handel's Operas, 1726-1741. Boydell & Brewer, London 2006. Reprint: The Boydell Press, Woodbridge 2009, ISBN 978-1-84383-268-3 , p. 133.

- ^ Editing management of the Halle Handel Edition: Documents on life and work. In: Walter Eisen (Hrsg.): Handel manual: Volume 4. Deutscher Verlag für Musik, Leipzig 1985, ISBN 3-7618-0717-1 , p. 225.

- ↑ a b c Christopher Hogwood: Georg Friedrich Handel. A biography (= Insel-Taschenbuch 2655). Translated from the English by Bettina Obrecht. Insel Verlag, Frankfurt am Main / Leipzig 2000, ISBN 3-458-34355-5 , p. 202 ff.

- ↑ Commerce Reference Database. ichriss.ccarh.org, accessed February 7, 2013 .

- ↑ a b Reinhard Strohm : Handel's pasticci. In: Essays on Handel and Italian Opera. Cambridge University Press 1985, Reprint 2008, ISBN 978-0-521-26428-0 , pp. 183 ff. (English).

- ^ A b c John H. Roberts: Arbace. In: Annette Landgraf, David Vickers: The Cambridge Handel Encyclopedia. Cambridge University Press, 2009, ISBN 978-0-521-88192-0 , pp. 47 f. (English)

- ↑ a b c Steffen Voss: Pasticci: Arbace. In: Hans Joachim Marx (Hrsg.): The Handel Handbook in 6 volumes: Das Handel-Lexikon , (Volume 6), Laaber-Verlag, Laaber 2011, ISBN 978-3-89007-552-5 , p. 560.

- ^ Roland Dieter Schmidt-Hensel: La musica è del Signor Hasse detto il Sassone ... , Treatises on the history of music 19.2. V&R unipress, Göttingen 2009, ISBN 978-3-89971-442-5 , p. 51.

- ↑ Carsten Binder: Plutarchs Vita Des Artaxerxes: A Historical Commentary, Verlag Walter de Gruyter , Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-11-020269-4 , p. 82 ff.

- ↑ Leonardo Vinci: Artaserse. parnassus art productions, accessed June 10, 2013 .

- ^ Artaxerxes a Singspiel. digital.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de, accessed on June 10, 2013 .

- ^ Bernd Baselt : Thematic-systematic directory. Instrumental music, pasticci and fragments. In: Walter Eisen (Ed.): Handel manual: Volume 3 , Deutscher Verlag für Musik , Leipzig 1986, ISBN 3-7618-0716-3 , p. 385 f.

- ↑ Winton Dean : Handel's Operas, 1726-1741. Boydell & Brewer, London 2006. Reprint: The Boydell Press, Woodbridge 2009, ISBN 978-1-84383-268-3 , pp. 128 f.

- ^ Editing management of the Halle Handel Edition : Documents on life and work. In: Walter Eisen (Ed.): Handel Handbook: Volume 4 , Deutscher Verlag für Musik , Leipzig 1985, ISBN 3-7618-0717-1 , p. 239.