Castrato

As castrati are singers called that before puberty a castration were subjected to the change of voice to stop and a beautiful soprano - or Alt also get -voice in adulthood. They sang in church and chamber music as well as in Italian opera performances . In the 17th to early 19th centuries, some castrati who had attained special virtuosity through early and targeted vocal training and who appeared in opera, achieved great admiration and fame. Castrato voices were used in numerous works by most of the great composers of the time, including Monteverdi , Alessandro Scarlatti , Handel , Mozart and Rossini .

history

Practice and consequences of castration

In late antiquity , later in Byzantium, and especially from the late 16th to the 19th century in Italy , boys with beautiful soprano or alto natural voices were sometimes castrated with the aim of enabling them to pursue a career as successful singers. In Italy the castrati were called musico (musicians), virtuoso (virtuoso) or sopranista (soprano) during this period . France was the only European country in the baroque period that officially and radically rejected not only castration, but also the castrati themselves and the castrato singing. Germany and Austria, on the other hand, were strongly influenced by Italian music and opera , especially in the 17th and 18th centuries , so that there were castrati there too. These were not all "imported" from Italy, but sometimes also operated on site. This is shown by the example of the composer Joseph Haydn , who would have almost been "sopranoized" in Vienna if his father had not refused his permission. At that time, even a castrato employed at the court advised against the intervention.

The parents or families had to give their consent for the operation, which probably often happened out of the hope of a financially profitable career for their son. According to the barber, the mostly 8 to 12 year old child had to ask for the procedure himself. Rosselli mentions a number of cases in which boys actually asked for an operation themselves for fear of losing their beautiful voices; There are even some letters of petition received in which boys wrote to various princes so that they would pay for the operation costs. In some families there were several neuters. A well-known and extreme example is the family of the composer Alessandro Melani , who had four brothers and two cousins who were all castrati, including Atto Melani .

The surgical procedure was not a major operation, but it did involve risks, as it was often carried out under non- sterile conditions and antibiotics were not yet known. Therefore, it is believed that some boys did not survive such an operation due to postoperative complications. However, more detailed information does not exist, especially since the operations were usually carried out in secret and there are no contemporary surveys. According to Rosselli, the sources give the impression that the surgical procedure itself was routine and normally proceeded without major problems.

After a castration, it wasn't just the vocal cords that stunted their growth. In the crucial pubertal developmental phase, the male body lacked both the important increase in the male sex hormone testosterone produced in the testes and the associated physical changes in the development of secondary sexual characteristics . For example, they had no beard growth, no male pattern baldness and were of course unable to procreate. Since the sex hormones are also responsible for the timely completion of longitudinal growth, some castrati were excessive (= eunuchoid high or gigantism). Another typical consequence of the lack of sex hormones was a relatively early onset of osteoporosis .

But they kept a relatively high or medium speaking voice, which probably resembled that of a high tenor . Depending on their predisposition, they tended to become full-bodied in advanced age, sometimes with a clearly perceptible breast attachment ( gynecomastia ).

But even a survived castration was no guarantee of a career as a famous and highly paid singer. Since the operation had to be carried out before the onset of puberty , usually between the ages of seven and twelve, there was no telling how the existing singing voice and musical talent of the boy concerned would develop.

Very few castrati made a great career on the opera stage. These enthused their audience beyond measure with an “unearthly voice”. Most of the castrati, however, were in the service of the Church, and sometimes they sang both in church and in opera. Others were looking for a job at the courts of cultivated and music-loving nobles (also in Germany). Not infrequently they also worked as music teachers or singing teachers (sometimes, but not always, after a great career, such as Pistocchi or Bernacchi ).

Some castrati did not achieve the hoped-for career as singers, and such men without sexual maturity probably had a difficult life. It was relatively common for castrati to enter the clergy or to go to a monastery as a monk (including Filippo Balatri , also Pistocchi or Giovanni Antonio Predieri (1679–1746)).

Training

It was not enough just to castrate a boy with gifted voices to make him a great singer. In order to achieve this, sound musical and vocal training was necessary, which also had to be financed. Some children were supported from the outset by a noble patron who had his own castrato singers trained as an ornament to his court music (example: Filippo Balatri). The Dukes of Mantua and Modena or the Grand Duke of Tuscany called important singers to their courts and awarded them titles such as virtuoso di camera , with which the singers also adorned themselves when performing in the opera houses of other cities. German nobles such as For example, the electors of Bavaria, Saxony, the Palatinate, or the King of Prussia “bought” young castrati in Italy through negotiators in order to have them trained at their own court.

Some official educational institutions in Italy played an important role, especially the famous conservatories in Naples : the Santa Maria di Loreto (founded 1535), the Pietà dei Turchini (founded 1584), the Poveri di Gesù Cristo (founded 1589) and the Sant'Onofrio a Porta Capuana (founded around 1600). All four institutions were originally orphanages and schools for poor abandoned boys. In the 17th century they specialized particularly in music and each set up a separate department for the training of small eunuchs. Because of their particularly precious and sensitive voices, they received a certain preferential treatment compared to the other students, for example heated rooms and something more sumptuous and better food. Many famous musicians and composers, some of whom had been students of such a conservatory themselves, such as Francesco Provenzale , Nicola Porpora and Francesco Durante, taught at the Conservatories of Naples . Porpora also gave private singing lessons and is considered to be one of the most important singing teachers of the era. From his school such famous castrato emerged as Giuseppe Appiani , Antonio Hubert “il Porporino” , Farinelli and Caffarelli .

In addition, there were other training centers all over Italy and of course private teachers, who were not infrequently castrati themselves. For example, the singing schools of the famous alto Francesco Antonio Pistocchi and Pier Francesco Tosi in Bologna were famous . The latter also left a rare and valuable treatise on song.

In their training, the castrati learned the perfect mastery and control of their breath , which was the foundation of their singing skills. In addition, there were singing exercises that specifically trained the softness, strength, fluency and coloratura ability of the voice, and especially the trill . If everything went well, in the end a small, gifted eunuch with a beautiful voice would have become a perfect singer of bel canto in its highest form, who could control his voice like an instrument: a virtuoso .

frequency

It is not known how many castrati there were or how many castrations were carried out, as the operations were kept secret and no precise surveys exist. This unclear documentary situation has caused some authors such as B. Franz Haböck is not prevented from making sometimes drastic estimates, which, however, have no real foundation. For example, there are statements that in Italy, despite official bans in the 18th century, an estimated "several thousand castrations per year" took place in secret.

On the other hand, Rosselli (1988), after careful and very objective investigations (including from church choirs at the time and opera singers known by name), came to a total of "only" several hundred castrati "at any time between approx. 1630 and 1750". Rosselli also concludes from available documents that the number of living castrati fell as early as 1740 or 1750. There is a certain tension between this and the fact that today's most famous castrati lived in the 18th century (probably for the simple reason that the music of Handel , Mozart and others, as well as their interpreters, are better known than the rather forgotten composers of the 17th century) .

The lack of clarity of the documentary also means that reliable and objective statements about how many (or whether most) castrati “did not succeed in a hoped-for great career as a singer” are simply not possible. Due to the lack of statements by those affected and because of the completely different socio-cultural historical situation, it is also not known whether a great operatic career was always the goal of the hopes, or whether it was not enough for poor parents to have a son cared for as a singer in a church was. Because it was still quite normal and above all honorable in the late 17th or at the turn of the 18th century that even famous singers like Cortona , Siface , Matteuccio or Nicolino , and later Caffarelli , Venanzio Rauzzini or Giuseppe Aprile , in churches or oratorios sang.

Relationships

A popular topic of speculation, in specialist literature and especially in popular scientific publications or novels, is the question of the castrato's erotic charisma and sexual ability to relate. The erectile function of neuters is also controversial. Since the singers rarely commented on their private life and left almost no biographical information, first-hand statements are extremely rare. An exception is Filippo Balatri , who in his memoirs admitted quite frankly with regard to sexuality: “ Questo non posso ” (“I can't do that”); and elsewhere: “I tell you honestly: if I were a man, a real man - I would have had many lovers! But you have ... put this dog on the chain in time. I can bark, but I can't bite ”. The famous Farinelli wrote similarly about the bride and groom (and himself) in a letter to a confidante on the occasion of a wedding at the Spanish royal court:

"So led to bed, you stayed in the dark to do what everyone did on the first night, only the one who writes you cannot get to know such pleasant dark nights."

On the other hand, there are a number of anecdotes about the amorous adventures of well-known castrati, mostly with women of higher society, who were often so enchanted by the singing of the castrati that it could degenerate into violent enthusiasm (similar to in more modern times with pop stars like the Beatles and others). However, whether all of these romance fantasies were really real, or how far they really went, will forever remain their mysteries. Some women are said to have hoped for the fulfillment of their sexual desires from neuters without exposing themselves to the risk of "shame" through pregnancy. The fact that the soprano Matteuccio , who was considered a heartthrob in his youth, was referred to in the register of deaths as “ virgine ” shows that there is not necessarily a lot to be said about such fantasies from the outside world .

A very tragic love story is that of the famous Siface , who was murdered by her brothers because of a relationship with a noblewoman. There are also some rare known cases of neuters who wanted to get married. In Catholic Italy this was impossible because the Church only allowed marriages if the man was able to procreate. Well known is the case of the famous castrato Cortona , who appealed to Pope Innocent XI. (1676–1689) asked for permission to marry, and the answer was: "... then you'd better neuter him".

In the Protestant north, however, some castrati actually managed to marry, e.g. B. 1666 Bartholomeo Sorlisi, who worked at the Dresden court, and in 1761 Filippo Finazzi , who settled in Hamburg as a composer in 1745. Often these cases also ended tragically, mostly because of resistance from society or the family of the woman concerned.

Some castrati had male admirers, especially when they appeared in female roles as adolescents. In general, it is not known exactly how far such relationships have gone, and some of them may just be rumors. Cardinal Antonio Barberini was said to have had a liaison with the soprano Marc'Antonio Pasqualini , whom he sponsored - as a substitute, so to speak, for the singer Leonora Baroni , who had previously rejected the cardinal. Also known is the case of the castrato Francesco de Castris called "Cecchino", who was " più femmina che uomo " ("more woman than man") and a not only musical favorite of the music-loving Prince Ferdinando de'Medici ; de 'Medici, like Barberini, is said to have a love affair with the prima donna Vittoria Tarquini .

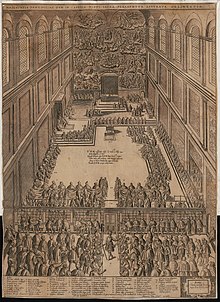

Castrati in church music

Since about the 4th century women have been banned from participating in polyphonic church chanting without such instructions being followed to a large extent. Castrati singing was firmly established in religious ceremonies in Byzantium in the 11th and 12th centuries at the latest. Up to the 16th century, falsettists or boys' voices were used in Europe and Italy for the high voices (soprano and alto) of church singing . The origin of the phenomenon in Italy is obscure. It is known, however, that by the middle of the 16th century at the latest there were castrato singers in Spain, presumably a legacy of the Islamic culture of the Spanish Middle Ages. Rosselli also reports that in the 1550s at least two or three Spanish castrati sang in the chapel of the Duke of Ferrara (under Ercole II and Alfonso II d'Este ), and that not much later the Duke of Modena, Guglielmo Gonzaga , was looking for castrato singers for his band.

In the papal chapel in Rome, Spanish singers had had the privilege to play the cantus since the 6th century. H. to sing the upper part. However, they were not listed as “ eunuchus ” in the Vatican files , so it is assumed that they were falsettists. The Spaniard Francisco de Soto is considered to be the first castrato to become a member of the papal chapel in 1562. The first two originally Italian castrati, who were also officially listed as " eunuchus ", were Pietro Paolo Folignati and Girolamo Rosini, who were hired in 1599 under Pope Clement VIII . This caused a scandal among the Spaniards: they saw their centuries-old privilege in danger; less because they were castrati than because of their Italian origins. However, the question also arises as to where these two Italian castrati came from so suddenly, if there is supposed to have been no Italian tradition of castrato singing up until then. As a result, all falsettists of the Capella Sistina were gradually replaced by castrati until 1625 , as they were far superior to the falsettists in terms of vocal beauty and abundance and were able to sing especially in the soprano range. An adult castrato singer also had an advantage over the boy's voices, musically and in terms of stamina, and he did not suddenly fail like a boy whose voice broke .

In Germany, the first castrati can be traced from 1572 at the latest in the Munich court chapel under Orlando di Lasso , from 1610 at the latest in the chapel of the Württemberger court, from 1637 at the latest in Vienna and from the middle of the 17th century in Dresden .

The need for castrati was increased by the fact that from the end of the 16th century popes introduced women to the Roman stages and in the Vatican States (at that time an area that included all of Lazio , Umbria , the Marche and Emilia ) was banned for reasons of "morality". This was especially true from the late 1670s (according to Rosselli). As a substitute, the female roles were then filled with boys or castrati "in travesti ".

Although castration was forbidden by papal decrees in the 18th century at the height of the castrato fashion and officially punished with excommunication , the popes did not dare to dismiss the castrati from the choirs of the Church. Not least because they would have simply had to abandon thousands of "cut" singers. In order to combat the preference for castrated singers and the widespread practice of castration at the root, Clement XIV (1769–1775) finally allowed women to sing the soprano parts in the churches and to appear again on the stages of the Vatican states. Nevertheless, around 1780 there were still more than 200 castrated singers employed in the churches of Rome alone, and secret castrations continued to take place in Italy. However, their number decreased at the turn of the 19th century. This, together with the slow decline of education at the conservatoires and the ideas of the Enlightenment and the French Revolution , which were also slowly taking hold in Italy, led to the slow extinction of the time of the great castrati. They first disappeared from the opera stage around 1830; however, in the mid-19th century there were still castrati in church choirs and in the papal chapel.

After the dissolution of the Papal States in 1870, the operations carried out to win castrati votes were finally abolished. It was not until November 22nd, 1903 that Pope Pius X wrote in his Motu proprio Tra le sollecitudini ( “On Church Music ” ) that only boys should be used for soprano and alto voices , and thus practically forbade the employment of castrati ( castrati ) in Church choirs. This ban deprived the castration practice of promoting a singing career the ultimate basis.

Alessandro Moreschi , the last castrato of the papal chapel, died in 1922. Sound documents have been preserved from him. In their assessment, however, these are not entirely unproblematic: on the one hand, because of the very imperfect recording technique of the time, which, above all, could only reproduce high voices poorly (and the higher up, the worse); on the other hand, because Moreschi was already stylistically influenced by verismo and therefore often allowed a "sobbing" song to be heard.

Castrati in secular music since the baroque

The castrati are an integral part of the European musical life of the Baroque and Classical periods, and they were often highly regarded. Most of the castrati sang in church, but in the course of the 17th century there were more and more appearances in the opera , where they were among the first superstars of music.

In baroque opera, there was a particular liking for the beauty and flexible softness of the high voices, soprano and alto, that is, female and castrato voices. In addition, there was a preference for the wonderful, the extraordinary and the supernatural, which the castrati met with their voices, but also through their unusual and, at least in their youth, often angelic appearance. Since the opera was the most important musical genre of the Italian Baroque and the whole of Italy, especially from the 17th to the 19th century, lived in an operatic frenzy, to which some other genres also owed their lives ( cantata , serenata , oratorio , motet, etc.) huge demand for male sopranos and altos.

These sang by no means subordinate roles, but usually the main male roles, Italian: Primo uomo (first gentleman or man) and the somewhat less important Secondo uomo (second gentleman or man). Whether someone could advance to Primo uomo depended on various qualities, above all on the power and volume of the voice, which of course were not the same for all singers. Furthermore from other musical qualities such as agility , expressiveness and scope, but not from the absolute height of the voice. So you don't necessarily have to be a soprano, although this was welcome.

In baroque opera it was completely normal for warlike heroes or kings, some of whom were real historical figures, such as Julius Caesar in Handel's Giulio Cesare (1724), or Emperor Nero in Monteverdi s L 'Incoronazione di Poppea (1651) and many others. , or mythological figures and gods, such as B. Apollo , sang in the high soprano or alto register. In many Italian or Italian-influenced operas of the 18th century, such as by Johann Adolph Hasse , Scarlatti , Vinci , Leo and others. a., there were almost exclusively roles for soprano and alto voices. It was also normal in a love duet for the higher voice to be sung by a man and the lower voice by a woman.

A famous example of this was the appearance of the young soprano Farinelli in 1725 at the side of the contralto Vittoria Tesi in a serenata by Hasse, where Farinelli sang the female role of Cleopatra and the Tesi her lover Marc 'Antonio . This is also an example of the custom of the time that young castrati made their debut in a female role in travesti and at the beginning of their career sometimes continued to sing female roles for a while before they switched to the hero roles that were actually intended for them. Very seldom did a castrato specialize in female roles throughout his entire career, like Giacinto Fontana , who worked in Rome and known as Farfallino .

The most famous castrati of the 18th century include Nicolino , Senesino , Farinelli , Carestini , Caffarelli and Antonio Bernacchi . Those who had an opera career could say they were lucky, especially financially, because the fees were a multiple of what one could earn in church services, although the competition of the theaters also drove up the prices for the sopranos of the church. This is attested, for example, for San Marco in Venice , where the castrato sopranos earned considerably more than the deep tenor and bass voices . Nevertheless (or perhaps because of it) many castrati sang both in the opera and in the church, such as Loreto Vittori (1600–1670), who shone both in the papal chapel and on the opera stage, or Giovanni Battista Minelli (1689–1762 ), who, in addition to a great operatic career throughout Italy, mainly served as a church singer in S. Petronio in Bologna and entered the clergy in 1735. Another example is Venanzio Rauzzini (1746–1810), who sang Cecilio in Mozart's Lucio Silla in Milan in late 1772 and early 1773 (Milan 1772/1773) and for whom the young composer also composed the famous motet Exsultate, jubilate for a church performance .

The last appearance of a great castrato on the opera stage took place in 1833, when Giovanni Battista Velluti (1780–1861) was on stage for the very last time in Meyerbeer's Il crociato in Egitto at the Teatro della Pergola in Florence. The vocal perfection and bravura, but also the expressiveness of the great castrati, had shaped the entire epoch of bel canto until then. The last great castrati Girolamo Crescentini , Luigi Marchesi , Gaspare Pacchierotti and Velluti passed on their art as singing teachers . Her students included important singers of the early 19th century such as Angelica Catalani , Isabella Colbran , Rosmunda Pisaroni , Luigia Boccabadati and Adelaide Tosi .

With the disappearance of the castrati from the opera stage, however, the art of singing gradually declined. This is how Gioachino Rossini expressed himself , who is said to have been saved from castration himself through the intervention of his mother as a child, in a conversation with Richard Wagner in 1860 :

“One cannot imagine the charm of the voice and the perfect virtuosity that - for lack of a certain something - these good people (= the castrati, author's note) possessed as a benevolent compensation, they were also incomparable singing teachers ... So the castrati disappeared and the custom of blending ceased. But this was the cause of the inexorable decline of the art of singing ... "

Rossini himself wrote his late work Petite Messe solennelle in 1863 for "twelve singers of the three sexes" , a strange, ironic utterance by a man at the age of his "sins of old age" (Péchés de vieillesse) .

Replacement in the 20th and 21st centuries

Since the practice of castration was finally discontinued, the casting of male roles in soprano or alto positions has posed a particular problem for early music performance. In the 20th century, it was customary for a long time to transpose such roles into typical male positions in order to achieve that of works from the 19th Century to meet listening expectations (→ Heldentenor ). With the development of historical performance practice, it has become accepted that changing the pitch of the voice affects the structure of the music. Especially in love duets in baroque operas, in which the two voices are often interwoven in the same position. Therefore, one makes do with female voices or countertenors , whose falsetto sounds clearly different from a castrato voice and was not accepted on the opera stage itself in the Baroque period. In the Italian Baroque, all voices that sang in their normal, natural register were called voce naturale . That was the alto and soprano registers for women, children and castrato voices (and of course also the tenor, baritone and bass registers for men). For technical vocal and physiological reasons, however, the voice of the falsettists was called voce artificiale , an “artificial voice”. Most falsetto (or countertenor) voices have a relatively breathy and not very voluminous sound that does not carry very far and is well suited for choral and consort music (and was used that way in historical times), but not good for the opera stage. At high altitudes they often appear forced. In contrast to the “natural” voices, falsetto voices usually sound much higher (up to a fourth or fifth) than they actually sing. This also applies to the relatively rare singers with a well-trained, voluminous and beautifully timbred falsetto voice (e.g. Philippe Jaroussky or Andreas Scholl ).

Women's voices were already a well-known substitute in the Baroque period, especially when a secondo uomo (second man or second man) in an opera could not be cast with a castrato. Singer Maria Maddalena Musi (especially in operas by Bononcini and Alessandro Scarlatti ) and contralto Vittoria Tesi ( e.g. in operas by Predieri , Sarro or Leo ) were among the singers who are known as performers of male roles and even primo uomo parts . . Handel also frequently used women in male roles in his operas and oratorios, including the mezzo-soprano Margherita Durastanti (title role in Radamisto , Sesto in Giulio Cesare ), Diana Vico (in Amadigi , Rinaldo ), Francesca Bertolli (in Poro , Sosarme , Esther ), Maria Caterina Negri (including in Ariodante , Arminio , Berenice ), or Caterina Galli (including title roles in Solomon , Alexander Balus ). This practice became even more relevant at the beginning of the 19th century, at the time of Rossini, when the last roles were still being written for castrati, although there were only a few left (only velluti from around 1812). Not least from this, the practice of so-called “ trouser roles ”, which is still known in Meyerbeer's Huguenots (1836), Verdi's Masked Ball (1859) or Richard Strauss ' Rosenkavalier (1911), developed .

In the film about the castrato Farinelli (1994) by Gérard Corbiau, modern possibilities of digital sound manipulation were used to mix a synthetic “castrato voice” from the voices of a soprano and a countertenor . The basis for this were audio documents of the last castrato Moreschi and contemporary descriptions. Even so, the result is of course not a real castrato vote.

Famous and important castrato singers

Unless otherwise stated, the following chronological list is based on information from the relevant book by Patrick Barbier and on a list of castrati (with further literature) on the website of the University of Bologna.

- Francisco Soto de Langa (1534–1619), is considered the first (Spanish) castrato of the Papal Chapel (since 1562).

- Giacomo Spagnoletto (16th century), Spanish castrato in the Papal Chapel

- Girolamo Bacchini (also: Fra Teodoro del Carmine) (active between approx. 1585 and 1607), singer and composer in Mantua; possibly sang in Monteverdi's Orfeo

- Pietro Paolo Folignati, first Italian castrato of the Papal Chapel (since 1599)

- Girolamo Rosini, second Italian castrato of the Papal Chapel (since 1599 or 1601)

- Giovanni Gualberto Magli (* before 1607–1625); sang u. a. in Monteverdi's Orfeo

- Loreto Vittori (1604–1670), famous soprano of the papal band, opera singer, composer, music teacher

- Baldassarre Ferri (1610–1680), famous soprano with career a. a. in Warsaw and Vienna.

- Marc'Antonio Pasqualini , called “Malagigi” (1614–1691), soprano of the papal band, opera singer in Rome and Paris

- Giovanni Andrea Bontempi (actually Angelini ; * around 1624–1705), singer, music writer and composer, active in Venice and Dresden

- Atto Melani (1626-1714), et al. a. in Paris; was also a diplomat

- Carlo Mannelli , known as Carlo del Violino (1640–1697), best known as a violinist and composer, active in Rome

- Vincenzo Olivicciani , called Vincenzino (1647–1726), soprano, worked mainly in Florence and at the Viennese imperial court

- Domenico Cecchi , called “il Cortona” (approx. 1650–1717/18), soprano, highly paid singer with a great career in Italy, Munich and Vienna.

- Giovanni Francesco Grossi, called " Siface " (1653–1697), alto, career a. a. in Rome, Modena and London; was murdered because of a love affair with a noblewoman.

- Pier Francesco Tosi (1654–1732), famous above all for his singing school: Opinioni de 'cantori antichi, e moderni o sieno osservazioni sopra il canto figurato (Bologna 1723)

- Clemens Hader von Hadersberg, called “Clementino” (around 1655–1714), soprano; active in Vienna, Munich, Venice, Brussels

- Francesco Antonio Pistocchi , called "Pistocchino" (1659–1726), contralto and singing teacher

- Andrea Adami da Bolsena (1663–1742), maestro di coro of the papal chapel from 1700

- Valeriano Pellegrini , called "Valeriano" (approx. 1663 (?) - 1746), soprano, career in Italy, Germany and England with Handel

- Matteo Sassano, called “ Matteuccio ” (1667–1737), famous as the “Nightingale of Naples”, soprano, a. a. active in Naples, Vienna and Madrid

- Giovan Battista Tamburini (approx. 1669 - approx. 1719), career as a secondo uomo, historically significant correspondence

- Valentino Urbani (proven 1690-1722), old, active in Italy and England, collaboration with Handel

- Pasqualino Tiepoli (around 1670–1742), mezzo-soprano, famous singer of the papal band , collaboration with Handel 1707-1708

- Nicolò Grimaldi , called "Nicolino" (1673–1732), famous soprano, sang a. a. Leading roles in operas by Alessandro Scarlatti, Handel and later in works by Hasse.

- Domenico Tollini, called "Domenichino" († 1720?), Soprano, career in Vienna and Italy

- Filippo Balatri (1682–1756), soprano, worked a. a. in Russia and Munich and left significant biographical records; later became a monk

- Pasquale Betti († 1752), alto, singer of the papal band, collaboration with Handel 1707-1708

- Francesco Finaia (1683–1753), famous soprano of the papal chapel, collaboration with Handel 1707-1708

- Antonio Bernacchi (1685–1756), contralto and singing teacher, sang a. a. some leading roles in operas by Handel

- Francesco Bernardi, called " Senesino " (1686–1758), famous contralto, sang numerous leading roles in Handel's operas

- Benedetto Baldassari (verified 1706–1739), soprano, active in Düsseldorf, Italy and in London with Handel

- Gaetano Berenstadt (1687–1734), alto, sang a. a. some supporting roles in Handel operas

- Matteo Berselli (proven from 1708 to 1721), high soprano, career in Italy, Dresden and London

- Giovanni Battista Minelli (1689–1762), in addition to a great operatic career throughout Italy, he served primarily as a church singer in S. Petronio in Bologna , and later as a clergyman

- Andrea Pacini , called " Il Lucchesino " (approx. 1690–1764), old, important career a. a. in Venice, Naples and in London with Handel; later entered the monastery

- Antonio Baldi (proven 1710–1735), Alt, secondo uomo; sang u. a. at Handel in London from 1725 to 1728

- Giacinto Fontana, called “ Farfallino ” (Perugia, 1692 - Perugia, 1739), soprano, famous as a female actor in Rome

- Domenico Annibali (* between 1700 and 1705–1779), old, in Dresden, but also with Georg Friedrich Händel

- Giovanni Carestini , called “il Cusanino” (approx. 1704 – approx. 1760), mezzo-soprano, a. a. Leading roles in Handel operas of the 1730s.

- Carlo Broschi, called " Farinelli " (1705–1782), the most famous of all castrati, career in Italy, London, Madrid

- Filippo Finazzi (1705–1776), soprano, conductor, singing teacher and composer, a. a. in Germany and Austria. Was also a soldier and got married in Hamburg (!).

- Angelo Maria Monticelli (approx. 1710 or 1712–1758), career a. a. in Vienna, London and Dresden

- Gaetano Majorano, called " Caffarelli " (1710–1783), one of the most famous castrati, also sang in late Handel operas, a. a. the so-called Largo “Ombra mai fù” in Serse

- Giuseppe Appiani (1712–1742), Alt, a. a. in Hasse's Demetrio

- Giovanni Bindi († 1750), career as a secondo uomo in Dresden and Berlin

- Felice Salimbeni (1712–1755)

- Giuseppe Belli († 1760), soprano, active a. a. in Dresden

- Giovanni Battista Mancini (1714–1800), soprano, singing teacher and writer, active a. a. in Vienna.

- Gioacchino Conti, called " Gizziello " (1714–1761)

- Antonio Uberti, called " Porporino " (1719–1783)

- Giovanni Manzuoli (approx. 1720–1782), a. a. Title role in Mozart's Ascanio in Alba (Milan 1771)

- Gaetano Guadagni (1728–1792), alto or mezzo-soprano, first Orfeo in Gluck's Orfeo ed Euridice (Vienna 1762), great career all over Europe

- Niccolò Peretti (around 1730 – after 1781) alto and impresario, a. a. in Italy, Hamburg and London.

- Giuseppe Aprile (1732-1813)

- Gaspare Pacchierotti [also: Gasparo Pacchiarotti] (1740–1821)

- Domenico Bedini (around 1745 - after 1795), a. a. first sesto ( primo uomo ) in Mozart's La clemenza di Tito (1791)

- Pietro Benedetti, called "Sartorino" (18th century), a. a. first sifare ( primo uomo ) in Mozart's Mitridate (1770/1771)

- Venanzio Rauzzini (1746-1810), a. a. Cecilio ( primo uomo ) in Mozart's Lucio Silla (Milan 1772/1773)

- Tommaso Consoli (approx. 1753-1810), u. a. Leading roles in the world premieres of Mozart's La finta giardiniera and Il re pastore (both 1775)

- Luigi Marchesi (1754-1829)

- Vincenzo dal Prato (1756-1828), u. a. first Idamante ( primo uomo ) in Mozart's Idomeneo (Munich 1781)

- Girolamo Crescentini (1762–1846)

- Giovanni Battista Velluti (1780–1861), is considered the last great castrato on the opera stage (1830 in Venice)

- Domenico Mustafà (1829–1912), soprano, director of the Papal Chapel.

- Alessandro Moreschi (1858–1922), last castrato of the Papal Chapel

Neuters as a subject in literature

Neuters have often been a topic in literature in recent decades, but a certain degree of caution is advised when it comes to imaginative speculations about their love life. In spite of some historical anecdotes, most castrati probably never had a love life, especially no sex life, and that was one of the reasons why they entered the monastery or the clergy relatively often.

- In the novel Melodien by Helmut Krausser , the figure of the castrato and composer Marc Antonio Pasqualini (1614–1691) is described with a real and fictional vita, and his path of suffering and his position in society are particularly addressed.

- Honoré de Balzac : Sarrasine in the Gutenberg-DE project .

- Novel The Virtuoso by Margriet de Moor (German 1994).

- In the detective novel Das Poison der Engel by Oliver Buslau (2006), a musicologist in a remote property trains an operated boy to become a castrato singer .

- In the historical crime novels Imprimatur , Secretum and Veritas by the Italian author couple Rita Monaldi and Francesco Sorti , the (historically documented) castrato Atto Melani is one of the central figures.

- In the novel Falsetto by Anne Rice , the story of Marco Antonio Treschi, called Tonio, is told, who was discovered in Venice at the age of 15 and became a castrato through an intrigue. Having become successful and famous, he seeks revenge.

- Roman Porporino or The Secrets of Naples by Dominique Fernandez (German 1976).

- The novel Der Kastrat by Richard Harvell (German 2011).

- Novel Der Kastrat by Lawrence Louis (German 1974).

- Novel Die Hyacinthenstimme by Daria Wilke (2019).

See also

- eunuch

- Conservatorio dei Poveri di Gesù Cristo

- Conservatorio della Pietà dei Turchini

- Conservatorio di Santa Maria di Loreto

- Conservatorio di Sant'Onofrio a Porta Capuana

literature

- Friedrich Agricola: Instructions for the art of singing. (after Tosis Opinioni de 'cantori antichi e moderni… Bologna 1723) . Berlin 1757. New edition in facsimile, ed. v. Thomas Seedorf . Bärenreiter, Kassel 2002.

- Patrick Barbier: Historia dos Castrados. (Portuguese version; title of the French original: Histoire des Castrats. ) Lisbon 1991 (originally Editions Grasset & Fasquelle, Paris, 1989).

- Cecilia Bartoli : Sacrificium. (Double CD and book). Decca Records 2009. (With her album, the mezzo-soprano Cecilia Bartoli recalls the suffering and art of the castrato singers of the 18th century).

- Rodolfo Celletti: History of Belcanto. Bärenreiter, Kassel 1989.

- Christian von Deuster: How did the castrati sing? Historical considerations. In: Würzburg medical history reports. Volume 25, 2006, pp. 133-152.

- Martha Feldman: The Castrato: Reflections on Natures and Kinds (= Ernest Bloch lectures. ). University of California Press, Berkeley 2015, ISBN 978-0-520-27949-0 .

- Wilhelm Ruprecht Frieling : Killer, art fart, castrato. Reports on unusual fates. Internet-Buchverlag 2011, ISBN 978-3-941286-69-6 , Chapter: The jubilating castrato.

- Hans Fritz: castrato singing. Hormonal, constitutional and educational aspects . Schneider, Tutzing 1994, ISBN 3-7952-0797-5 , (= anthology of music . Volume 13, also dissertation University of Music and Performing Arts Graz 1991).

- Franz Haböck : The singing art of the castrati. Universal-edition ag, Vienna 1923.

- Franz Haböck: The castrati and their art of singing, a singing-physiological, cultural and music-historical study. German publishing company, Stuttgart 1927.

- Michael Heinemann : Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina and his time (= great composers and their time. ) Laaber-Verlag, Laaber 1994, ISBN 3-89007-292-5 .

- Corinna Herr: Singing against the “order of nature”? Neuters and Falsettists in Music History. Preface by Kai Wessel , Bärenreiter, Kassel u. a. 2013, ISBN 978-3-7618-2187-9 (also revised version of the habilitation thesis Universität Bochum 2009, under the title: Highly singing men - singing against the “order of nature”? ).

- Silke Herrmann: Looking for traces: castrate singers between anecdote and archive: body, voice, gender. Kulturverlag Kadmos , Berlin 2014, ISBN 978-3-86599-197-3 (also dissertation Uni Erfurt 2008).

- René Jacobs : There are no more neuters, what now? Booklet text for the CD: Arias for Farinelli. Vivicagenaux , Academy for Early Music Berlin, R. Jacobs, published by Harmonia mundi, 2002–2003.

- Wilhelm Keitel , Dominik Neuner : Gioachino Rossini. Albrecht Knaus, Munich 1992.

- Hubert Ortkemper: Angels against their will. The world of the castrati. Another opera story. Henschel, Berlin 1993, ISBN 3-89487-006-0 .

- Ank Reinders: neuters. Origin, heyday and decline. Wißner, Augsburg 2015, ISBN 978-3-89639-976-2 .

- Juliane Riepe: singer in the church. For practice in 18th century Italian music centers . Academia; accessed on January 1, 2020

- HC Robbins Landon (Ed.): The Mozart Compendium - his life his music. Droemer Knaur, Munich 1991, ISBN 3-426-26530-3 .

- John Rosselli: The Castrati as a Professional Group and a Social Phenomenon, 1550-1850. In: Acta Musicologica. Volume 60, fascicule 2, May-August 1988, pp. 143-179.

- John Rosselli: Castrati. In: John Rosselli: Singers of Italian Opera. The history of a profession. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1992, ISBN 0-521-41683-3 , pp. 32-55.

- Piotr O. Schulz: The emasculated Eros. A cultural history of the eunuchs and castrati. Artemis & Winkler, Düsseldorf / Zurich 1997, ISBN 3-538-07056-3 , in particular pp. 251-256.

- Richard Somerset-Ward: Angels & Monsters. Male and Female Sopranos in the Story of Opera, 1600-1900. Yale University Press, New Haven CT et al. a. 2004, ISBN 0-300-09968-1 .

- Christine Wunnicke : The Tsar's Nightingale. The life of the castrato Filippo Balatri. Claassen, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-546-00248-2 (see also the author's website, accessed on October 9, 2017).

Results of exhumations

- Maria Giovanna Belcastro, Antonio Todero, Gino Fornaciari, Valentina Mariott: Hyperostosis frontalis interna (HFI) and castration: The case of the famous singer Farinelli (1705–1782). In: Journal of Anatomy , July 2011, PMC 3222842 (free full text) (English)

- Kristina Killgrove: Castration Affected Skeleton Of Famous Opera Singer Farinelli, Archaeologists Say , June 1, 2015, summary of the results of Farinelli's exhumation from Forbes / Science, accessed October 4, 2019

- Alberto Zanatta, Fabio Zampieri, Giuliano Scattolin, Maurizio Rippa Bonati: Occupational markers and pathology of the castrato singer Gaspare Pacchierotti (1740-1821) , in: Scientific Reports , Article No. 28463 (2016), accessed online on 4. January 2020

Web links

- Sound sample: Ave Maria sung by Alessandro Moreschi

- Michael Malkiewicz: castrato . In: Oesterreichisches Musiklexikon

- Joachim Risch: Rossini's last sin of old age. ( Memento from October 24, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Collegium Cantorum Cologne

- Falk Häfner: The music of the castrati. Cecilia Bartoli: "Sacrificium"

- "Sacrifice and seducer". focus.de, German / Italian TV documentary, ZDF, August 6, 2010, 11.45 p.m.

- Castrati e falsettisti . Archivio del canto, 2014; extensive listing of literature about neutered people in general and individual neutered people in particular; accessed on November 7, 2015.

Individual evidence

- ^ Patrick Barbier: Historia dos Castrados. Lisbon 1991, pp. 213-231.

- ↑ This is what Haydn reported to his biographer Griesinger; the term “soprano” is original. HC Robbins Landon : Haydn . Molden, Vienna a. a. 1981, p. 36.

- ^ Patrick Barbier: Historia dos Castrados. Lisbon 1991, pp. 32-33.

- ^ John Rosselli: Castrati . In: Singers of italian Opera: the history of a profession. Cambridge University Press, 1995, Chapter 2, pp. 32–55, here: 38–39, Google Books (English)

- ^ Charles Ancillon (1659-1715), Robert Samber: Eunuchism display'd, describing all the different sorts of eunuchs ... Written by a person of honor [ie Charles Ancillon]. (Original work translated into English by Robert Samber) E. Curll, London 1718, ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive ) (Original work: Charles Ancillon: Traité des eunuques. 1707 [reprinted: (publié par) Dominique Fernandez, Ramsay, Paris 1978, ISBN 2-85956-070-X .]) NLM Catalog .

- ↑ a b c Video Stefan Schneider, Cristina Trebbi: Sacrifice and seducer. German / Italian TV documentary, ZDF, August 6, 2010, 11:45 p.m. in the ZDFmediathek , accessed on February 2, 2014. (offline)

- ^ John Rosselli: The Castrati as a Professional Group and a Social Phenomenon, 1550-1850. 1988, p. 152.

- ^ Patrick Barbier: Historia dos Castrados. Lisbon 1991, pp. 35-37.

- ^ John Rosselli: Castrati . In: Singers of italian Opera: the history of a profession . Cambridge University Press, 1995, Chapter 2, pp. 32-55, here: 37; Google Books (English)

- ↑ An examination of Farinelli's remains revealed a size of about 1.90 m. Maria Giovanna Belcastro, Antonio Todero, Gino Fornaciari, Valentina Mariott: Hyperostosis frontalis interna (HFI) and castration: The case of the famous singer Farinelli (1705–1782). In: Journal of Anatomy , July 2011, PMC 3222842 (free full text) (English)

- ↑ Kristina Killgrove: Castration Affected Skeleton Of Famous Opera Singer Farinelli, Archaeologists Say , June 1, 2015, summary of the results of the exhumation from Forbes / Science (English) accessed October 4, 2019

- ↑ Pacchierotti was also exhumed and was about 1.91 m tall. Alberto Zanatta, Fabio Zampieri, Giuliano Scattolin, Maurizio Rippa Bonati: Occupational markers and pathology of the castrato singer Gaspare Pacchierotti (1740-1821) . In: Scientific Reports , Article No. 28463 (2016), nature.com (English), accessed on January 4, 2020

- ^ Maria Giovanna Belcastro, Antonio Todero, Gino Fornaciari, Valentina Mariott: Hyperostosis frontalis interna (HFI) and castration: The case of the famous singer Farinelli (1705–1782). In: Journal of Anatomy , July 2011 (English) PMC 3222842 (free full text)

- ^ Alberto Zanatta, Fabio Zampieri, Giuliano Scattolin, Maurizio Rippa Bonati: Occupational markers and pathology of the castrato singer Gaspare Pacchierotti (1740-1821) . In: Scientific Reports , Article No. 28463 (2016), nature.com (English), accessed on January 4, 2020

- ↑ Statements about the speaking voice of castrati are rare and contradicting. Horace Walpole claimed after meeting Senesino in 1740 that Senesino had spoken “like a shrill little pipe” (“... we thought it a fat old woman; but it spoke in a shrill little pipe, and proved itself to be Senesini”) . This seems at least doubtful, on the one hand because Senesino was not a soprano but an alto, and a shrill voice is therefore improbable; on the other hand, because Walpole obviously harbored a very negative attitude or aversion to the castrato, and therefore apparently chose particularly spiteful words.

- ↑ Christian von Deuster: How did the castrati sing? Historical considerations. 2006, pp. 133-152; here: p. 136.

- ^ John Rosselli: The Castrati as a Professional Group and a Social Phenomenon, 1550-1850. In: Acta Musicologica. Volume 60, fascicule 2, May-August 1988, pp. 143-179, here: pp. 158-173.

- ↑ In any case, significantly more Europeans and Italians (both in relative terms and in absolute numbers) lived in monasteries at that time than at the beginning of the 21st century.

- ^ John Rosselli: The Castrati as a Professional Group and a Social Phenomenon, 1550-1850 . In: Acta Musicologica. Volume 60, fascicule 2, May-August 1988, pp. 143-179, here: p. 173.

- ^ Patrick Barbier: Historia dos Castrados. Lisbon 1991, p. 39.

- ↑ Christine Wunnicke: The Tsar's Nightingale. The life of the castrato Filippo Balatri. Munich 2001.

- ^ Patrick Barbier: Historia dos Castrados. Lisbon 1991, p. 38.

- ^ Patrick Barbier: Historia dos Castrados. Lisbon 1991, pp. 54-56.

- ^ Patrick Barbier: Historia dos Castrados. Lisbon 1991, pp. 57-58.

- ^ Rodolfo Celletti: History of Belcanto. Bärenreiter, Kassel 1989, p. 79.

- ^ Patrick Barbier: Historia dos Castrados. Lisbon 1991, pp. 69-74.

- ^ Opinioni de 'cantori antichi, e moderni o sieno osservazioni sopra il canto figurato (Bologna 1723). German translation by: Johann Friedrich Agricola: Instructions for the art of singing. Berlin 1757. New edition in facsimile, ed. v. Thomas Seedorf . Bärenreiter, Kassel 2002.

- ^ Patrick Barbier: Historia dos Castrados. Lisbon 1991, pp. 64-69.

- ^ Rodolfo Celletti: History of Belcanto. Bärenreiter, Kassel 1989, pp. 9-12.

- ^ John Rosselli: The Castrati as a Professional Group and a Social Phenomenon, 1550-1850. In: Acta Musicologica. Volume 60, fascicule 2, May-August 1988, pp. 143-179, here: pp. 156-158.

- ^ A b Franz Haböck: The singing art of the castrati. Vienna 1923, pp. 236-238.

- ↑ a b Fritjof Miehlisch: Contribution to the endocrinology of castrate singers. Medical dissertation, Cologne 1974, p. 10.

- ↑ a b Christian von Deuster: On the pathology of the human voice. Medical historical considerations on castrato singing. In: Würzburg medical history reports. Volume 23, 2004, pp. 39–60, here: pp. 39 and 43.

- ↑ d. H. in each year of this period. Please note that this cautious formulation also implies that within 20 years (within this period) the same people will be involved to a not inconsiderable number of times per year.

- ^ John Rosselli: The Castrati as a Professional Group and a Social Phenomenon, 1550-1850. In: Acta Musicologica. Volume 60, fascicule 2, May-August 1988, pp. 143-179, here: pp. 147, 158.

- ^ John Rosselli: The Castrati as a Professional Group and a Social Phenomenon, 1550-1850. In: Acta Musicologica. Volume 60, fascicule 2, May-August 1988, pp. 143-179, here: p. 158.

- ^ John Rosselli: The Castrati as a Professional Group and a Social Phenomenon, 1550-1850. In: Acta Musicologica. Volume 60, fascicule 2, May-August 1988, pp. 143-179, here: p. 145.

- ↑ Christine Wunnicke: The Tsar's Nightingale - The life of the castrato Filippo Balatri. Allitera-Verlag, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-86906-125-2 , p. 90.

- ↑ Patrick Barbier: Farinelli, the castrato of kings. Econ, Düsseldorf 1995, p. 136.

- ↑ It was about the wedding of the Infante Philip with Louise Élisabeth of France, a daughter of Louis XV. Like almost all princely weddings, it was not a love marriage and Louise Élisabeth in particular was very unhappy in this marriage.

- ^ John Rosselli: The Castrati as a Professional Group and a Social Phenomenon, 1550-1850. In: Acta Musicologica. Volume 60, fascicule 2, May-August 1988, pp. 143-179, here: p. 162.

- ^ Patrick Barbier: Historia dos Castrados. Lisbon 1991, pp. 157-159.

- ^ Patrick Barbier: Historia dos Castrados. Lisbon 1991, p. 162.

- ^ "A dí 15 ottobre 1737 - Matteo Sassano, di anni 80, abitante al Rosariello di Palazzo, vergine, sepolto al Carminiello di Palazzo" (Napoli, Parrocchia di S. Giovanni Maggiore, Liber Mortuorum , c.431). In: U. Prota-Giurleo: "Matteo Sassano ...", ..., p. 118. Here after: Grazia Carbonella: "Matteo Sassano il rosignolo di Napoli". In La Capitanata. Volume 21, 2007, pp. 235-260; bibliotecaprovinciale.foggia.it (PDF accessed on October 17, 2017.

- ↑ Luca Della Libera: Grossi, Giovanni Francesco, detto Siface . In: Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani. Volume 59, 2002, Treccani (Italian). Retrieved October 17, 2019

- ↑ Tim Ashley: Filippo Mineccia: Siface; L'amor castrato. CD review on the website of: Gramophone (English; accessed October 17, 2019).

- ↑ On June 7th, 1587 Pope Sixtus V ordered with the impotence decree that a man had to have real semen, that is, from the testicles, otherwise he was not allowed to marry, and thus demanded the ability to procreate ( potentia generandi ) for marriage. Uta Ranke-Heinemann: Eunuchs for the kingdom of heaven . Complete paperback edition, 5th edition, Droemer Knaur, Munich 1996, ISBN 3-426-04079-4 , p. 258 ff.

- ^ Patrick Barbier: Historia dos Castrados. Lisbon 1991, p. 143 and p. 163.

- ^ Patrick Barbier: Historia dos Castrados. Lisbon 1991, pp. 163-164.

- ^ Patrick Barbier: Historia dos Castrados. Lisbon 1991, pp. 174-179.

- ↑ Georges Dethan: The Young Mazarin. Thames and Hudson, London 1977, OCLC 878082988 , pp. 63f.

- ^ A b Roger Freitas: The Eroticism of Emasculation: Confronting the Baroque Body of the Castrato. in: The Journal of Musicology. Volume 20, No. 2, Spring 2003, pp. 196–249, here: pp. 215–216.

- ↑ Francesco de Castris dit Cecchino and Vittoria Tarquini dite la Bombace on the Quell'usignolo website (French; accessed October 27, 2019) -

- ↑ Christian von Deuster: How did the castrati sing? Historical considerations. 2006, p. 133 f.

- ^ Patrick Barbier: Historia dos Castrados. Lisbon 1991, pp. 14–15 and p. 143.

- ^ A b John Rosselli: The Castrati as a Professional Group and a Social Phenomenon, 1550-1850. In: Acta Musicologica. Volume 60, fascicule 2, May-August 1988, pp. 143-179, here: p. 146.

- ↑ This is not necessarily synonymous with “soprano”, since the upper part was also in the alto range in many vocal polyphony works of the 15th and especially the early 16th century.

- ^ Patrick Barbier: Historia dos Castrados. Lisbon 1991, p. 15.

- ^ Patrick Barbier: Historia dos Castrados. Lisbon 1991, pp. 14-15.

- ^ A b Michael Heinemann: Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina and his time. Laaber-Verlag, 1994, p. 32.

- ↑ a b Patrick Barbier: Historia dos Castrados. Lisbon 1991, pp. 15-16.

- ↑ a b Patrick Barbier: Historia dos Castrados. Lisbon 1991, p. 143.

- ↑ Uta Ranke-Heinemann: Eunuchs for the kingdom of heaven. Munich 1996, p. 263.

- ^ A b c Rodolfo Celletti: History of Belcanto. Bärenreiter, Kassel 1989, p. 113.

- ^ A b John Rosselli: The Castrati as a Professional Group and a Social Phenomenon, 1550-1850. In: Acta Musicologica. Volume 60, fascicule 2, May-August 1988, pp. 143-179, here: p. 147.

- ↑ Peter Browe: On the history of emasculation. A study of religious and legal history. Breslau 1936, p. 96.

- ↑ The Osservazioni per ben regolare il coro dei cantori della Cappella Pontificia (Rome 1711)

- ^ Patrick Barbier: Historia dos Castrados. Lisbon 1991, p. 144.

- ↑ a b c Patrick Barbier: Historia dos Castrados. Lisbon 1991, p. 145.

- ^ Patrick Barbier: Historia dos Castrados. Lisbon 1991, p. 146.

- ↑ Christian von Deuster: How did the castrati sing? Historical considerations. 2006, p. 134 f.

- ↑ Christian von Deuster: How did the castrati sing? Historical considerations. 2006, pp. 140 and 145.

- ↑ Tra le sollecitudini. Section V “The Singers.” 13. vatican.va; Retrieved September 4, 2013.

- ↑ Jürgen Kesting : The great singers. Volume 1. Hoffmann and Campe, Hamburg 2008, ISBN 978-3-455-50070-7 , p. 57 f.

- ↑ Patricia Howard: The Modern Castrato: Gaetano Guadagni and the Coming of a New Operatic Age. Oxford University Press, 2014, ISBN 978-0-19-936522-7 , pp. 192 f. doi: 10.1093 / acprof: oso / 9780199365203.001.0001 .

- ^ John Rosselli: The Castrati as a Professional Group and a Social Phenomenon, 1550-1850. In: Acta Musicologica. Volume 60, fascicule 2, May-August 1988, pp. 143-179, here: pp. 162-169.

- ^ Rodolfo Celletti: History of Belcanto. Bärenreiter, Kassel 1989, pp. 8–9, also pp. 13–14.

- ↑ René Jacobs: “There are no more castrati, what now?” Booklet text for the CD: Arias for Farinelli. Vivicagenaux, Academy for Early Music Berlin, R. Jacobs, published by Harmonia mundi, 2002–2003, p. 41.

- ^ Patrick Barbier: Historia dos Castrados. Lisbon 1991, pp. 103-104.

- ^ Patrick Barbier: Historia dos Castrados. Lisbon 1991, pp. 146-147.

- ^ A b Giovanni Andrea Sechi: Minelli, Giovanni Battista. In Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani. Volume 74, 2010 ( accessed October 11, 2017 at treccani.it ).

- ↑ a b H. C. Robbins Landon: The Mozart Compendium - his life his music. Munich 1991, p. 278.

- ^ Don White: Meyerbeer in Italy. Booklet text for CD Giacomo Meyerbeer - Il crociato in Egitto. Opera Rara (ORC 10), 1991/1992, p. 41. See also the list of performers on p. 3 in the printed libretto for this performance ( I-MOe: Modena Biblioteca Estense Universitaria, Collocazione: MD.H.04.15 on the Corago information page of the University of Bologna; accessed on October 20, 2017).

- ↑ The Grove Music article wrongly claims that Velluti's last appearance was in Giuseppe Nicolini's Il conte di Lenosse at the Teatro La Fenice in Venice. See Elizabeth Forbes: Velluti, Giovanni Battista. In: Grove Music Online (English; subscription required; free preview ).

- ↑ Barbier also writes that Velluti retired from the stage in 1830 and only gave a concert in the following year. Patrick Barbier: Historia dos Castrados. Lisbon 1991, p. 269.

- ^ Wilhelm Keitel, Dominik Neuner: Gioachino Rossini . Albrecht Knaus, Munich 1992, pp. 222-223.

- ↑ Rossini in Paris-Passy 1863, quoted from Joachim Risch: Rossini's last old sin ( memento of October 24, 2007 in the Internet Archive ).

- ↑ René Jacobs: There are no more neuters, what now? Booklet text for the CD: Arias for Farinelli. Vivicagenaux, Academy for Early Music Berlin, R. Jacobs, published by Harmonia mundi, 2002–2003, pp. 45–51, here pp. 47–48.

- ^ Patrick Barbier: Historia dos Castrados. Lisbon 1991, p. 9.

- ↑ René Jacobs: There are no more neuters, what now? Booklet text for the CD: Arias for Farinelli. Vivicagenaux, Academy for Early Music Berlin, R. Jacobs, published by Harmonia mundi, 2002–2003, pp. 45–51.

- ↑ a b Patrick Barbier: Historia dos Castrados. Lisbon 1991.

- ^ Castrati e falsettisti on the website of the University of Bologna; accessed on October 9, 2017.

- ↑ Elena Gentile: Cecchi, Domenico, detto il Cortona . In: Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani. Volume 23, 1979, accessed on treccani.it on October 13, 2017.

- ↑ Francesca Fantappiè: academia.edu .

- ↑ a b c Juliane Riepe: Singer in the Church, On Practice in Italian Music Centers of the 18th Century . Online at Academia , pp. 74-75.

- ↑ Dagmar Glüxam, article "Tollini, Domenico", in: Österreichisches Musiklexikon online : musiklexikon.ac.at accessed on October 11, 2017.

- ↑ Christine Wunnicke: The Tsar's Nightingale. The life of the castrato Filippo Balatri. Munich 2001.

- ^ Giovanni Polin: Monticelli, Angelo Maria. In Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani. Volume 76, 2012, online on Treccani website: treccani.it, accessed October 11, 2017.

- ↑ Gabi Maria Volkmann: Bindi, Giovanni (called Porporino). In: Saxon Biography. ed. from the Institute for Saxon History and Folklore e. V., arr. by Martina Schattkowsky, online edition: saebi.isgv.de, accessed on October 13, 2017.

- ↑ HC Robbins Landon: The Mozart Compendium - his life his music. Munich 1991, p. 277.

- ↑ HC Robbins Landon: The Mozart Compendium - his life his music. Munich 1991, p. 291.

- ↑ HC Robbins Landon: The Mozart Compendium - his life his music. Munich 1991, p. 276.

- ↑ HC Robbins Landon: The Mozart Compendium - his life his music. Munich 1991, pp. 279-280.

- ↑ HC Robbins Landon: The Mozart Compendium - his life his music. Munich 1991, p. 282.

- ↑ Illuminating on this topic are the autobiographical statements of Filippo Balatri, which can be considered to be almost unique in the history of the castrati. See Christine Wunnicke: The Tsar's Nightingale. The life of the castrato Filippo Balatri. Munich 2001.