The Rosenkavalier

| Work data | |

|---|---|

| Title: | The Rosenkavalier |

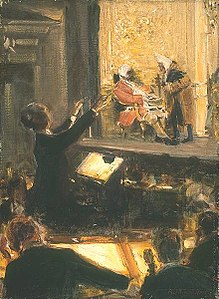

Robert Sterl : Ernst von Schuch conducts the Rosenkavalier (scene from the 1st act, ox / notary) |

|

| Original language: | German |

| Music: | Richard Strauss |

| Libretto : | Hugo von Hofmannsthal |

| Premiere: | January 26, 1911 |

| Place of premiere: | Royal Opera House Dresden |

| Playing time: | approx. 3 ½ hours |

| Place and time of the action: | Vienna around 1740 |

| people | |

|

|

The Rosenkavalier. Comedy for Music (op. 59) is an opera in three acts . The music comes from the German composer Richard Strauss , the libretto from the Austrian writer Hugo von Hofmannsthal . The work was on 26 January 1911, the Royal Opera House Dresden premiere .

action

The opera is set in Vienna during Maria Theresa's first reign , around 1740.

first act

In the bedroom

Maria Theresa Fürstin Werdenberg, wife of a field marshal, has fun with her seventeen-year-old lover, Count Octavian Rofrano, in the absence of her husband. The scene is disturbed by a knock on the door, but it's not her husband, but her cousin, Baron Ochs auf Lerchenau. In a hurry, Octavian disguises himself as a chambermaid and in this masquerade can hardly avoid the intrusiveness of the baron, who brags about his insatiable lust. The baron is in financial difficulties and intends to marry the young Sophie, the daughter of the recently ennobled, nouveau riche Herr von Faninal. The field marshal offers him Octavian - of whose presence the baron does not suspect - as bridegroom leader ("Rosenkavalier"). The lever , the morning reception in the princess's bedroom with a large mess of supplicants, schemers, staff and others, is woven into this course of action , which is shaped by a quodlibet .

Second act

In the house of the Lord of Faninal

Sophie, daughter of Herr von Faninal, is preparing for the arrival of the Rosenkavalier, who is to ceremonially bring her a silver rose, thereby announcing the arrival of the bridegroom. The Rosenkavalier is Octavian; when he faces Sophie, he falls in love with her. The baron who then appears is characterized by a rowdy demeanor, which repels his future bride. When Octavian and Sophie secretly kiss, they are betrayed by Valzacchi and Annina, an Italian intriguing couple. The baron is not worried about this, but Octavian tells him to let go of Sophie. Finally he wounds the baron with the sword. Sophie's father intervenes and threatens to send her to the monastery for life if she refuses to marry. The injured baron finally receives a letter from Annina in which the princess' maid invites him to a rendezvous.

Third act

In an inn

The baron meets with the supposed chambermaid in a tavern. However, Octavian, Valzacchi and Annina set a trap for the baron. While the baron is intrusive, the veiled Annina appears with four children who are supposed to be from him. A police officer intervenes, whereupon the baron completely loses his composure. Finally, Sophie and her father join in, who is now against the planned marriage alliance. The field marshal also appears, appeases the policeman and chases the baron away. But she has no choice but to release Octavian for the connection with Sophie.

layout

libretto

Hofmannsthal's libretto on the Rosenkavalier is based on the novel The Adventures of Chevalier Faublas by Jean-Baptiste Louvet de Couvray and Molière's comedy The Lord from the Province ( Monsieur de Pourceaugnac ). The dramatic figures in Hofmannsthal's poem come partly from the novel, but also have models in the figures of the Italian Commedia dell'arte . They are types and lively, realistic characters. Hofmannsthal later describes the beginnings of the Rosenkavalier in retrospect as follows: “The figures were there and acted before us even before we had names for them: the Buffo, the old man, the young woman, the lady, the 'Cherubin'. (...) The story arose from the eternally typical relationship between the characters, almost without knowing how. ”( Der Rosenkavalier. Zum Geleit, 1927)

Together the figures also form a complex network of relationships. “One needs the other, not only in this world, but also in a metaphysical sense, so to speak. (...) They all belong to one another, and what is best lies between them: it is instantaneous and eternal, and here is room for music, ”wrote Hofmannsthal in the unwritten epilogue to“ Rosenkavalier ” (1911). Through the art of speaking that he put into the mouths of the characters, Hofmannsthal created realistic characters with human features, with humor, with a certain fate, more than he himself suspected. Therefore, the viewer is not indifferent to the plot and the characters. As a spectator, you take part in what is happening on the stage, as is the case with very few pieces. This may be the secret of the audience's success and love for this masterpiece on the music stage. Hofmannsthal invented his own language for this piece, which is close to the Viennese dialect. The text itself is now part of world literature, and that is very rare among texts for the music stage.

Hofmannsthal also emphasized that the text did not want to try to revive the historic Rococo period ; rather, "more of the past is in the present than one suspects". “Behind this was the secret wish to create a half-imaginary, half-real whole, this Vienna around 1740, a whole city with its stalls that stand out against one another and mix with one another, with their ceremonies, their social classifications, their way of speaking or rather their ways of speaking differently according to the classes, with the anticipated closeness of the great court above all, with the always felt closeness of the folk element ”( to the escort ).

The Rosenkavalier is definitely a contemporary piece , based on the Austria of the time around 1910. It can be read as a criticism of the customs of the Danube Monarchy - which Hofmannsthal himself certainly adhered to - or as an apology of the sacred marital status: hidden in the piece is a conservative tendency to expose and dismantle the depravity of the adulterer and lascivious, in order to finally let conjugal love triumph. Before the Baron's arrival, Sophie prays to God: “The mother is dead and I am all alone. I stand up for myself. But marriage is a sacred state ”. The relationship between libertinage and marital ties in the piece is not as clear as it may first appear. The young Count Octavian also bears certain features of the voluptuous Baron Ochs, and Sophie is not a chaste bride, but lets herself be seduced, although she was promised to marry. It remains to be seen whether the marriage between Sophie and Octavian will actually be concluded in the end. Hofmannsthal himself once said that what he had to say about marriage he said in his comedies. For him marriage was the Christian sacrament.

Another approach is the fact "time". Hofmannsthal lets the Field Marshal reflect on time, how it flows and what it causes, in the fate of people and in people themselves.

music

After his revolutionary advances in the operas Salome and in particular Elektra , Strauss chose a noticeably more moderate pace in Rosenkavalier. The harmonic sharpness that leads to the limits of tonality in Elektra is largely eliminated . In terms of tonal color, too, after the brutal outburst in Elektra, he again approaches the more supple sound ideal of Salome . The Viennese waltz plays a special role in the second and third act. Strauss adopted a theme from the waltz Dynamiden - Secret Attraction by Josef Strauss . The musical idea thus coincides with the Hofmannsthals, who does not want to try to revive the historic Rococo period. It is not the typical rococo dances such as the minuet, the lander and the polonaise that are processed, but the Viennese waltz, which actually belongs to the 19th century. Richard Strauss has been repeatedly accused of not having waltzes in the 18th century. Apparently, the waltz was only supposed to give local flavor, that is, to symbolize the Vienna scene, at least not to create any proximity to the operetta .

After the drama in Salome and Elektra , Richard Strauss longed for a cheerful subject; Strauss pays homage to his greatest role model Mozart with a lively musical comedy in the style of opera buffa . Even the plot of the mistaken comedy about a nobleman chasing after a maid is reminiscent of Le nozze di Figaro . Of course, Strauss remains a child of his time in his tonal language, especially because of his lush, sensual instrumentation (the orchestra needs around 100 musicians).

Orchestral line-up

3 flutes (3rd also Piccolo ), 2 oboe , 1 English horn (also 3. oboe), 2 clarinets in B (in A and C), 1 clarinet in D (also in it, B and A), 1 Bassetthorn ( also bass clarinet), 3 bassoons (3rd also contrabassoon); 4 horns , 3 trumpets , 3 trombones , 1 bass tuba ; Timpani (1 player), percussion (3 players: bass drum , cymbals , triangle , tambourine , glockenspiel , large ratchet , stirring drum , small military drum , bells , castanets ), 1 celesta , 2 harps ; 16 violins I, 16 violins II, 12 violas , 10 cellos , 8 double basses .

Incidental music in the III. Act: 2 flutes, 1 oboe, 1 C clarinet, 2 Bb clarinets, 2 bassoons; 2 horns, 1 trumpet; snare drum, 1 harmonium, 1 piano; Violins I and II, violas, cellos, double basses (string quintet one or more times, only not two each)

Work history

Emergence

In 1927 Hofmannsthal wrote a foreword to the Rosenkavalier, which at that time had already become the most successful piece of the collaboration with Strauss. According to him, the scenario was created in March 1909 in Weimar in conversation with his friend Harry Graf Kessler , to whom the first edition is also dedicated. At this dedication , the friendship between Kessler and Hofmannsthal almost broke. Kessler, who (presumably rightly) valued his contribution to the creation higher than Hofmannsthal wanted to admit, insisted on the designation "employee", while Hofmannsthal had only apostrophized him as "helper" in the first version. Hofmannsthal finally managed to say: “I dedicate this comedy to Count Harry Keßler, whose collaboration it owes so much. HH "

Hofmannsthal carried out the text alone. Kessler only received text excerpts, gave advice, which Hofmannsthal did not necessarily implement or heed. Richard Strauss probably had a greater influence, especially through his wish for a more theatrical redesign of the second act after the handing over of roses to the duel between Ochs and Octavian and a lot more.

Hofmannsthal downplayed Kessler's share to Richard Strauss. After the libretto was written, Hofmannsthal went to Berlin to present Strauss the plan for a comic opera. “His listening has been truly productive. I felt how he distributed unborn music to the hardly born figures. ”The further collaboration took place by letter; On May 16, 1910, Strauss reports that he will now begin composing the third act. The text version was ready in June 1910; then Hofmannsthal reworked them in places for the opera version. In January 1911, the work was then premiered at the Royal Opera House in Dresden under the direction of Ernst von Schuch and in a production by Max Reinhardt .

The final text differs in some places from the first version; it is shorter, some things have been rearranged and rewritten; Parts have also been expanded for the sake of the music. Two drafts for the text from 1909, some with stage sketches, have been preserved; also an early version of the first act.

The title was controversial until shortly before going to press. Different names were suggested, so the ox on Lerchenau and the silver rose should appear in the title. Hofmannsthal also suggested the name Rosenkavalier , which Strauss and Kessler rejected. Female acquaintances in the Hofmannsthal area advised against Ochs auf Lerchenau in the title and also advocated Rosenkavalier . Richard Strauss' wife made the final decision; Finally, Strauss commented: “So Rosenkavalier, the devil will get him”.

Strauss had a knowledgeable trustee for the premiere in the conductor Ernst von Schuch in Dresden. He mentioned the “new play opera” for the first time in a letter to the conductor in May 1909 (letter dated May 9). Schuch had previously conducted the premieres of the Strauss operas Feuersnot , Salome and Elektra in Dresden. Strauss wrote to him again and again in order to provide precise ideas about the line-up, the instrumentation and even the rehearsal planning. He wished for a premiere in December 1910 and tried to achieve this through the most precise suggestions for the rehearsal process. Finally, the premiere took place on January 26, 1911. Strauss also conducted some rehearsals himself to give the singers his interpretation of the characters.

The Rosenkavalier required high acting skills from the singers. The director Georg Toller, originally commissioned with the production, was not up to this claim. It was Hofmannsthal who, with Max Reinhardt as director and Alfred Roller as stage and costume designer, put first-class artists through to the scenic realization. Reinhardt headed the Deutsches Theater Berlin from 1905 and was one of the leading directors of the stage. Strauss was a regular guest in Reinhardt's performances, and it was Reinhardt who had given him the encounter with Hofmannsthal. The stage designer Alfred Roller and the composer Gustav Mahler had carried out decisive reformatory innovations in the scenic quality of opera performances at the Vienna Court Opera since 1903 . The collaboration with both theater men proved to be extremely fruitful in the future as well: in 1920, Strauss founded the Salzburg Festival together with Reinhardt and Roller .

For the Dresden Rosenkavalier production, Roller produced extremely detailed drafts of scenes in close collaboration with Hofmannsthal, which at the time were unprecedented in the field of opera. Max Reinhardt, on the other hand, was initially only approved as an advisory director. He was not allowed to enter the stage, but had to give his stage directions from the backdrop. Strauss did everything in his power to get Reinhardt through as a director against apparently existing anti-Semitic resentments at the Dresden court opera, which he finally succeeded in doing. Nevertheless, Reinhardt's name was not mentioned in the program booklet.

The first performance of the Rosenkavalier was an overwhelming success, with the audience responding more enthusiastically than the critics, who were particularly astonished by the anachronistic waltzes.

The Dresden artistic director Nikolaus Graf von Seebach found the work to be too long and feared negative reactions from the Dresden court, especially when Baron Ochs in Lerchenau described his love life in the first act. Strauss gave his consent to deletions, which then turned out to be much more extensive (and, as Strauss complains: destroying the musical structure) than he had assumed. His relationship with the Dresden Opera clouded over, and Strauss also complained heavily to Schuch about these interventions, which he had not authorized (letter of May 1, 1911). He attacks the director of Seebach because of his opportunism: “You write that the lines in the Rosenkavalier only last 15 minutes. Is it worth destroying the architecture of a work of art in order to save a full 15 minutes? Is everything wrong. The reason lies elsewhere. A nobleman who behaves on the stage as many nobles behave at court and in agriculture is not pleasant in the eyes of the noble gentlemen general managers. "

After the success of Dresden, other opera houses quickly followed suit. By the end of the year, the work had been performed on more than forty stages at home and abroad, including outstanding productions such as in Munich (direction: Felix Mottl ), Milan (direction: Tullio Serafin ) and Berlin (direction: Carl Muck ). Performance concepts in the spirit of Reinhardt and Roller dominated for a long time. It was not until the sixties that there were performances among others. in Wiesbaden (director: Claus Helmut Drese ), in Stuttgart (director: Götz Friedrich ), in Frankfurt (director: Ruth Berghaus ) and Salzburg (director: Herbert Wernicke ) other conceptual approaches.

Cast of the premiere

| role | Pitch | Conductor : Ernst von Schuch |

|---|---|---|

| Field Marshal of Werdenberg | soprano | Margarethe Siems |

| Baron Ochs on Lerchenau | bass | Carl Perron |

| Octavian | Mezzo-soprano | Eve from the East |

| Faninal | baritone | Karl Scheidemantel |

| Sophie | soprano | Minnie Nast |

| Head butcher | soprano | Riza Eibenschütz |

| Valzacchi | tenor | Hans Rudiger |

| Annina | Old | Erna friend |

| Police superintendent | bass | Julius Puttlitz |

| Steward / singer | tenor | Fritz Soot |

| notary | bass | Ludwig Ermold |

| Landlord / animal dealer | tenor | Josef Pauli |

| milliner | soprano | Elisa Stünzner |

| Three noble orphans | Soprano, mezzo-soprano, soprano | Marie Keldorfer, Gertrud Sachse, Paula Seiring |

| Lark Exchange Leiblakai | bass | Theodor Heuser |

| The marshal's lackeys | 2 tenors, 2 basses | Josef Pauli, Wilhelm Quidde, Rudolf Schmalnauer, Robert Büssel |

Film adaptations

The treatment for the first film adaptation of the Rosenkavalier as a silent film comes from Hofmannsthal himself, the opera plot only forms part of the film. Directed by Robert Wiene . The first performance took place on January 10, 1926 in the Royal Opera House in Dresden; Richard Strauss conducted the orchestra himself.

- 1926 - Robert Wiene - Der Rosenkavalier (1926)

- 1962 - Paul Czinner - Der Rosenkavalier (1962)

- 1984 - Hugo Käch - Der Rosenkavalier (1984)

In addition to the movies, there are several TV versions, including:

- Der Rosenkavalier , with Benno Kusche , Brigitte Fassbaender , Gwyneth Jones , Lucia Popp , Manfred Jungwirth , Anneliese Waas, David Thaw, Gudrun Wewezow, Francisco Araiza ; Director: Otto Schenk , Conductor: Carlos Kleiber , Orchestra and Choir of the Bavarian State Opera ( Bayerische Staatsoper 1979)

Trivia

For the opera, which was created under the working title Comedy for Music , there was speculation in 1910 about the final name of Ochs von Lerchenau .

After the success of the premiere in 1911, a “Rosenkavalier” special train traveled from Berlin to Dresden. Cigarettes were given the name "Rosenkavalier", and in a carnival parade Rosenkavaliers rode on horseback, behind which Richard Strauss and his stage characters followed weeping. Satirical poems were written - in other words, this work was on everyone's lips.

Hugo von Hofmannsthal was the first - and only - Picasso collector in Austria. From the royalties for his libretto for the Rosenkavalier he bought the early self-portrait “Yo Picasso” in Heinrich Thannhauser's gallery in Munich.

Text output

- Dirk O. Hoffmann (Ed.): Der Rosenkavalier: Text versions and line commentary. Hollitzer, Vienna, 2016, ISBN 978-3-99012-348-5 .

- Joseph Kiermerier-Debre (ed.): Der Rosenkavalier. Comedy for Music (Dtv Library of First Editions). Dtv, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-423-02658-8 .

- Hugo von Hofmannsthal (text), Richard Strauss (music): Der Rosenkavalier. Comedy for music in 3 acts . Fürstner Verlag, Berlin 1911 (opera version)

- Willi Schuh (ed.): Hugo von Hofmannsthal, Richard Strauss, Der Rosenkavalier. Versions, film scenarios, letters . Fischer, Frankfurt / M. 1972, ISBN 3-10-031533-2 .

- Hugo von Hofmannsthal: Opera poems . Residenz-Verlag, Salzburg 1994, ISBN 3-7017-0885-1 (also contains the text versions)

- Kurt Pahlen (Ed.): Richard Strauss "Der Rosenkavalier". Text book with explanations . Atlantis Musikbuchverlag, Mainz 1997, ISBN 3-254-08018-1 .

- Rudolf Hirsch, Clemens Köttelwesch, Heinz Rölleke, Ernst Zinn (eds.): Hugo von Hofmannsthal. Complete Works. Critical edition . Organized by the Free German Hochstift. S. Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt / M.

- Vol. 23. Opera poems 1: Der Rosenkavalier. Text, text genesis and explanations, additional materials (unwritten afterword; for guidance; director's sketch); Certificates and letters about the origin; Sources . Ed. V. Dirk O. Hoffmann and Willi Schuh. 1986, ISBN 3-10-731523-0 (research results on the work)

literature

- Christian: Beck-Mannagetta: The ox from Lerchenau. A historical consideration of "Der Rosenkavalier" . Edition present, Vienna 2003, ISBN 3-7069-0229-X .

- Matthias Viertel (Ed.): Der Rosenkavalier or is it still possible to compose a comedy in the 20th century? (Hofgeismar Protocols; Vol. 321). Evangelical Academy, Hofgeismar 2000, ISBN 3-89281-230-6 .

Discography

- Vienna Philharmonic , Vienna State Opera Choir (conductor: Robert Heger ) 1933, with Lotte Lehmann , Elisabeth Schumann , Maria Olczewska , Richard Mayr , Hermann Gallos , Viktor Madin , Bella Paalen , Karl Ettl and Aenne Michalsky

- Bavarian State Orchestra (conductor: Clemens Krauss ) 1944, Preiser Records, with Viorica Ursuleac , Georgine von Milinkovic , Adele Kern , Ludwig Weber , Georg Hann

- Staatskapelle Dresden (conductor: Rudolf Kempe ) 1950, Gala GL 100.633, with Margarete Bäumer (Marschallin), Tiana Lemnitz (Octavian), Ursula Richter (Sophie), Kurt Böhme (Ochs), Hans Löbel (Faninal)

- Wiener Philharmoniker (Conductor: Erich Kleiber ) 1952, Decca 25025-D, with Maria Reining (Marschallin), Sena Jurinac (Octavian), Hilde Güden (Sophie), Ludwig Weber (Ochs), Alfred Poell (Faninal), Anton Dermota (singer )

- Philharmonia Orchestra London (Conductor: Herbert von Karajan ) 1956, EMI 7 49354 1, with Elisabeth Schwarzkopf (Marschallin), Christa Ludwig (Octavian), Teresa Stich-Randall (Sophie), Otto Edelmann (Ochs), Eberhard Waechter (Faninal), Nicolai Gedda (singer)

- Wiener Philharmoniker (conductor: Georg Solti ) 1968-69, Decca 417 493-2, with Régine Crespin (Marschallin), Yvonne Minton (Octavian), Helen Donath (Sophie), Manfred Jungwirth (Ochs), Otto Wiener (Faninal), Luciano Pavarotti (singer)

- Vienna Philharmonic (conductor: Karl Böhm ) 1969 ( Salzburg Festival , live), Deutsche Grammophon 445 338-2, with Christa Ludwig (Marschallin), Tatiana Troyanos (Octavian), Edith Mathis (Sophie), Theo Adam (Ochs), Otto Wiener (Faninal)

- Munich Philharmonic Orchestra (Conductor: Christian Thielemann ) 2009, Decca DDD 001620102, Video 0440 074 3340 9 DH 2, with Renée Fleming (Marschallin), Sophie Koch (Octavian), Diana Damrau (Sophie), Franz Hawlata (Ochs), Jonas Kaufmann ( Singer)

Web links

- The Rosenkavalier in the Gutenberg-DE project

- Der Rosenkavalier : Sheet Music and Audio Files in the International Music Score Library Project

- Plot and libretto of Der Rosenkavalier in German at Opera-Guide

- Discography of Der Rosenkavalier at Operadis

- Group picture: Alfred Roller with Richard Strauss, Ernst v. Schuch, Max Reinhardt, Hugo v. Hofmannsthal, Nikolaus Graf von Seebach and others.

- Satirical poem Der Rosenkavalier , from the Kladderadatsch of February 5, 1911

- Rosenkavalier satire from the Kladderadatsch of April 2, 1911 (makes fun of the censorship of the "offensive passages" of the opera, which despite the great success of the Dresden premiere in Berlin had not yet been performed)

Individual evidence

- ↑ (see the correspondence between Strauss and Hofmannsthal)

- ↑ For guidance , 1927

- ↑ a b Ernst von Schuch - Richard Strauss: A letter exchange . A publication by the Richard Strauss Society, ed. by Julia Liebscher and Gabriella Hanke Knaus. Henschel Verlag, Berlin 1999. ISBN 978-3-89487-329-5

- ↑ The Rosenkavalier. In: Neue Freie Presse , January 27, 1911, p. 10 (online at ANNO ).

- ↑ Bryan Gilliam: Der Rosenkavalier - Ariadne on Naxos - The woman without a shadow . In: Richard Strauss Handbook. Edited by Walter Werbeck. JB Metzler, Stuttgart and Weimar and Bärenreiter, Kassel 2014, ISBN 978-3-476-02344-5 , p. 192.

- ↑ quoted from: Laurenz Lütteken: Richard Strauss. Modern music . Philipp Reclam jun. GmbH & Co.Kg 2014, ISBN 978-3-15-010973-1 , p. 154

- ↑ Bryan Gilliam: Der Rosenkavalier - Ariadne on Naxos - The woman without a shadow . In: Richard Strauss Handbook. Edited by Walter Werbeck. JB Metzler, Stuttgart and Weimar and Bärenreiter, Kassel 2014, ISBN 978-3-476-02344-5 , p. 193.

- ↑ Theater and Art News. In: Neue Freie Presse , January 31, 1910, p. 9 (online at ANNO ).

- ↑ Artur Prince : In Opernzug. In: Berliner Tagblatt, March 6, 1911, accessed on June 3, 2019.

- ^ Discography on Der Rosenkavalier at Operadis