Tonality (music)

In music, tonality is a system of hierarchical pitch relationships that are related to a keynote (as the “center” of a scale ) or a tonic (center of a key ).

The term tonality

The term tonality ( French tonalité ) comes from Alexandre Choron (1810) and was borrowed from François-Joseph Fétis in 1840. Although Fétis used the term generally for the musical order and spoke of types of tonality rather than of a single system, today the term mostly refers to the major-minor tonality , which is also called the diatonic , functional or harmonic tonality, precisely the system of musical structure that was in use in the classical period and that most popular music around the world still uses today.

Tonality is therefore a property of large parts of occidentally influenced music : Tonal music refers to a tonal center within the prevailing system of 12 semitones . This consists of a certain tone (the basic tone or target tone) and the triads based on this and related triads . With the narrower term tonic , Jean-Philippe Rameau already meant a chord ( l'accord tonique ). It is not synonymous because a unison melody can evoke tonality.

This special diatonic or functional tonality means that the chords occurring in a piece of music are put together according to certain patterns and follow one another. In the context of harmony theory, some chords are evaluated as dissonances in need of resolution , others as self-contained consonances . A deviation from the tonal center causes tension to build up, a return to relaxation. The keys used in tonal music can also be determined. Strictly speaking, this definition is about the major - minor tonality that has become almost a matter of course in our culture .

Tonality can be expressed in a more general way if one starts with a tone system , i.e. a selection of tones with a fixed pitch. Depending on the system, there can be one, two or more tones with a greater rest effect, closing effect or dissolving effect. This quality can already be seen in unison melodies. If the music develops away from these calm tones or builds up tension to them, the approach to a calm tone and the dissolution of the tensions is felt again as a calm effect or even as a final effect and a tonal, possibly only temporary center is reached. As an example, the medieval church scales can be cited, which produced melodies that cannot fully conform to the major-minor scheme without losing their characteristics.

history

Aristoxenos ' music theory is an early example of applied mathematics from classical antiquity shortly before Euclid and is the first to deal with sound systems exactly. He built music theory strictly on perception with the ear and is therefore considered the leading harmonist. He rejected the acoustic music theory of the Pythagoras school , which defined intervals using numerical ratios, as a stray into a foreign field, and criticized their uncheckable hypotheses ( Archytas ) and their inaccurate flute and string experiments. Euclid, who in his musical work Teilung des Canon offered a Pythagorean-modified version of the diatonic Aristoxeneic tone system, at the same time proved a number of sentences against the harmony of Aristoxenus.

All of the later ancient music theorists in the area of harmony adopted the musical terminology from Aristoxenus. Aristoxeneer (e.g. Psellos ) is the name of those music theorists who orientated themselves on the teaching of Aristoxenus and kept away from the Pythagorean direction. However, they erroneously removed all mathematics from his teaching, that is, all axioms and proofs and many definitions, as well as the entire experimental perception-related foundation. This led to a number of misunderstandings.

Representatives of an Aristoxene-Pythagorean compromise line were also Eratosthenes and above all Ptolemy .

Ptolemy continued to work through Boethius , who handed down the dispute between the Pythagoras and Aristoxenos schools in the Latin-speaking area and who had a major influence on the medieval and modern tone system theory. In medieval music, the aristoxenic forms of the octave, which are also known as octave genres, got a practical meaning for the church modes.

Tonal music then replaced the modal music of the Middle Ages, which was based on the church modes, whereby many of the characteristics of tonality already applied there. The authentic cadence occupies a central position in it, at its end it is sometimes even exclusive. In the 18th century only the major and minor keys were left. However, the minor still remains ambiguous as a minor of the same name and a parallel minor. The theory of stages and the theory of functions were developed as systems of musical analysis, but retrospectively when their laws had long since been overridden, namely at the end of the 19th century mainly by Hugo Riemann . One opponent of this direction was Johannes Brahms . Quote Hermann von Helmholtz : The predominance of the tonal acts as a connecting link for all tones of a piece.

The cadenza in classical music as a principle of order since 1700 for about 200 years is a harmonic-tonal and weight-metric grouping. The individual voices move towards a conclusion that is perceived as a center of tonality. If you move away from the center, this is felt as an unstressed, raised step. Rhythmic aspects also contribute to the perception of tonality: a first tone, a first sound is perceived as a tonality. In the 19th century, Richard Wagner and other composers gradually widened the limits of tonality until it could no longer be viewed in terms of level or function in musical impressionism (e.g. Claude Debussy ).

The atonal music of the Vienna School (including the composers Arnold Schönberg , Alban Berg and Anton Webern ) brought about the liberation from the limitations of tonality in the 20th century . A critic of atonal composing was u. a. the old Paul Hindemith , who constructed a tonal system on the basis of consonance / dissonance ratios of the intervals in his instruction in musical composition (1937–39). The Hindemith system, however, could not prevail, as systems such as the twelve-tone technique , which was further developed into serial music , had long been established.

While atonality predominates in New Music , almost all areas of popular music today are characterized by a more or less expanded tonality.

Between tonality and atonality

The expansion and the resulting dissolution of tonality can essentially be tied to three basic principles which, when taken together - as in twelve-tone music, for example - guarantee atonality in the narrower sense. Since these principles - (overgrown) chromatics , expanded, no longer functional sound affinities and the “ emancipation of dissonance ” - appeared together at the beginning of the 20th century, they are often (incorrectly) subsumed under the term atonality in the relevant literature, although each is an independent music-theoretical and music-historical phenomenon.

Chromatics

Comprising 12 semitones existing chromatic scale, due to its symmetric structure as opposed to asymmetric major - and minor - scales and other diatonic modes no (unique) root and thus meets the conditions of atonal music in melodic terms. The same also applies to other scales, such as whole-tone scales , reduced scales or in general “ modes with limited transposition possibilities ” (in short: Messiaen modes ). Through the excessive use of altered pitches, the striving effect of leading tones and the associated feeling of a fundamental tone is suppressed. Nevertheless - with the appropriate harmonic design - even extremely chromatic works, such as Johann Sebastian Bach's B minor - fugue from the Well-Tempered Clavier , can definitely be assigned to a key (here B minor) and thus to a keynote ( B ) (Schönberg: "Bach sometimes worked with the twelve tones in such a way that one might be inclined to call him the first twelve-tone composer"):

Conversely, a keynote can be missing even in purely diatonic works, such as in György Ligeti's 15th Piano Etude White on White .

See also: chromatics , alteration

Extended sound affinity

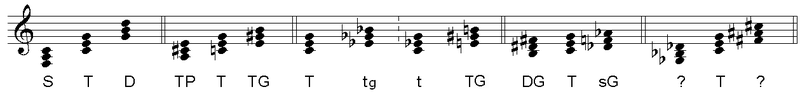

The tonality (more precisely: "harmonic tonality") is realized in a very small space in the authentic cadence . It contains all the diatonic degrees of a major or minor key and is represented by the tonic , subdominant and dominant (short: T, S and D) related main functions . This tonal network was first expanded with the introduction of distant third-third related sounds (so-called mediants : TP and TG), which are no longer conductive and therefore no longer of diatonic origin. In the years that followed, many composers developed harmonies that could no longer be fitted into a common key, such as "mediant variants" (T - tp and t - TG) or chromatic connections such as that of a leading sound which is a semitone step below the tonic (DG) and of the " free Neapolitan " (sG). They experimented with it up to sounds that no longer have any relation to each other (e.g. sounds that are separated by a tritone ):

Although these triads can each be related to a root note (C major chord, E flat minor chord, etc.), they have no common tonal center; the “form-forming tendency of harmony” is suspended. Especially for compositions in which the superordinate reference tonic does not sound at all and a key can only be read from the corresponding preliminary drawing , the terms free tonality and atonicality have become established to distinguish them from the actual atonality . Analogous to the twelve-tone technique, this phenomenon can be explained or interpreted as a “method of only related sounds” or as “permanent modulation ” (the transition from one tonal center to another). Chromatics and extended sonic affinity go hand in hand insofar as they both introduce an extensive range of notes.

Emancipation of dissonance

Like symmetrical scales, symmetrical sounds do not have a (unambiguous) tonal center, even if - like the excessive triad (in melodic minor ) or the diminished seventh chord (in harmonic minor ) - they are ladder (a). This property - the ambiguity of so-called " vague chords " - is used in " enharmonic modulation" to bridge several steps in fifths by first relating them to one root note and later to the other. Similarly ambivalent - and closely related to these - are sounds that are composed of components of different keys (see bitonality , polytonality ) - for example the simultaneous sounding of a C major chord with its median E major, or the (minor- ) Subdominant F minor with the dominant G major (b). The more dissonant the result , the further apart the individual harmony complexes in the circle of fifths are (c). The catchphrase of "emancipated dissonance" refers to the fact that such sound structures are no longer resolved according to the rules of traditional musical composition. This also applies (and in particular) to harmonies that no longer have any thirds , such as fourth chords and their further developments (the “ mystical chord ” of Alexander Scriabin or the “ Turangalîla chord ” of Olivier Messiaen ), which, according to traditional understanding, are unresolved reserve constructions be perceived, but in fact consciously leave the tonality (d). In its final consequence, the emancipation of dissonance means the complete equality of all intervals and the harmonies formed from them - up to diatonic, whole-tone or chromatic cluster (e):

In contrast to the concept of atonality, Schönberg did not reject the term “emancipated dissonance”, but wrote: “My school, to which men like Alban Berg, Anton Webern and others belong, does not strive to establish a tonality, but does not exclude it completely. The procedure is based on my theory of the 'emancipation of dissonance'. ”In fact, even extreme dissonance and tonality do not contradict each other if dissonant tones are used as“ coloristic additions ”to an otherwise tonal event. An example of this is the second movement from Arvo Pärt's collage about BACH (1964).

See also: Quartenharmonik , Cluster

Historical development towards atonality

Franz Liszt - in his late piano pieces - and Alexander Scriabin had already touched on atonality . The overgrown use of chromaticism during the late Romantic period or by composers like Max Reger had an atonal tendency. The use of bitonality or polytonality , the use of two or more keys at the same time, led to the border area of atonality. The first phase, which consists in giving up traditional harmony, is also called "free atonality". Schönberg tried to create a principle of order within atonal music and developed the method of “composition with twelve only related tones” (later apostrophized as the twelve-tone technique ), which he began in 1923 (in some of the Five Piano Pieces op.23 and in most of the movements of the Suite for piano op.25 ) was first used. This twelve-tone principle does not necessarily guarantee atonality, but merely a largely even distribution of the twelve tempered semitones within the compositional movement. Depending on the row structure and the vertical organization of the tones, it is entirely possible to compose pieces in row technique that are perceived as tonal. Schönberg even deliberately constructed some of his complementary rows in such a way that, after the vertical unbundling of their hexachords, they can be aligned with a tonal center. Through appropriate material disposition, he then generates alternating tonal and atonal zones with a single basic row. In the piano piece op. 33a and in the piano concerto op. 42, this approach is combined with a clear intention in terms of form and content (cf. “Theory of Tonality” (2013), p. 155 ff). The twelve-tone technique was further developed into serialism after the Second World War and dominated the avant-garde of "serious" music during the 1950s in Europe. Other important pioneers of atonal music were, besides Alban Berg and Anton von Webern (who, together with Schönberg , are subsumed under the so-called Second Viennese School ) Ernst Krenek , Igor Stravinsky , Béla Bartók and many others.

See also

literature

- Wilhelm Paul Becker: Harmonics and Tonality. Foundations of a new music theory (= European university publications. Series 36: Musicology. Vol. 258). Lang, Frankfurt am Main a. a. 2009, ISBN 978-3-631-58688-4 .

- Michael Beiche: Tonality . In: Concise dictionary of musical terminology . Vol. 5, ed. by Hans Heinrich Eggebrecht and Albrecht Riethmüller , editors Markus Bandur. Steiner, Stuttgart 1972 ( online ).

- Roland Eberlein : The emergence of tonal sound syntax . Lang, Frankfurt am Main a. a. 1994, ISBN 3-631-47450-4 .

- Martin Eybl: Tonality. In: Oesterreichisches Musiklexikon . Online edition, Vienna 2002 ff., ISBN 3-7001-3077-5 ; Print edition: Volume 5, Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Vienna 2006, ISBN 3-7001-3067-8 .

- Hellmut Federhofer : Chord and voice guidance in the music-theoretical systems of Hugo Riemann, Ernst Kurth and Heinrich Schenker (= Austrian Academy of Sciences. Philosophical-Historical Class. Meeting reports. 380 = Publications of the Commission for Music Research. H. 21). 2nd, corrected edition. Publishing house of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna 2009, ISBN 978-3-7001-0385-1 .

- Wilfried Neumaier: What is a sound system? A historical-systematic theory of the occidental sound systems, based on the ancient theorists, Aristoxenus, Eucleides and Ptolemaios, presented with the means of modern algebra (= sources and studies on the history of music from antiquity to the present . Volume 9 ). Lang, Frankfurt am Main a. a. 1986, ISBN 3-8204-9492-8 (also: Tübingen, Universität, Dissertation, 1985).

- Benedikt Stegemann: Theory of Tonality (= pocket books on musicology. 162). Noetzel, Wilhelmshaven 2013, ISBN 978-3-7959-0962-8 .

Individual evidence

- ^ Additional authors: Reti, 1958; Simms 1975, 119; Judd, 1998; Dahlhaus 1990

- ↑ English article: en: Tonality

- ↑ a b c d Article Aristoxenus

- ↑ Footnote: Aristoxenos defined the following terms on a purely musical basis: interval , tone system , tone , semitone , third tone , quarter tone , ..., diatonic , chromatic and enharmonic tone system , duration , rhythm .

- ↑ Lars Ulrich Abraham: Harmony . 2 volumes. Laaber Verlag

- ^ Arnold Schönberg: Style and Thought: Essays on Music , ed. by Ivan Vojtech. Frankfurt a. M. 1976, p. 28

- ↑ Carl Dahlhaus: Investigations into the origin of harmonic tonality . Kassel 1968

- ^ Arnold Schönberg: Structural Functions of Harmony . London 1954; German translation: The form-forming tendencies of harmony , Mainz 1957

- ^ Arnold Schönberg: Harmony . Vienna 1911. 7th edition 1966, p. 296 ff.

- ^ Arnold Schönberg: The form-forming tendencies of harmony , p. 186