Alexander Nikolaevich Scriabin

Alexander Nikolayevich Scriabin ( Russian Александр Николаевич Скрябин , scientific transliteration Aleksandr Nikolaevich Skrâbin ; and Alexander Skryabin ; emphasis: Alexánder Scriabin ; * December 25, 1871 . Jul / 6. January 1872 greg. In Moscow , † April 14 jul. / 27 April 1915 greg. Ibid) was a Russian pianist and composer .

Life and family

Scriabin was the son of a lawyer and diplomat from the military aristocracy. His mother, a concert pianist, died a year after he was born. Since his father completed diplomatic training after the death of his wife, Scriabin grew up mainly with his aunt Lyubov Scriabina. She also gave him his first piano lessons, because even as a toddler he showed great musical talent (at the age of five he was able to play melodies he had heard and improvise on the piano). At the age of ten he was admitted to the Moscow Cadet School at his own request (his father and aunt opposed it).

From 1888 to 1892 Scriabin studied composition with Anton Arensky and Sergei Taneyev and piano with Vasily Safonow at the Moscow Conservatory . Moscow's most renowned private music teacher at the time, Nikolai Swerev , prepared for the Conservatory . However, since Scriabin's composition studies were overshadowed by conflicts with his teacher, he finally made the decision not to graduate as a composer. In 1892 Scriabin finished his piano studies with the small gold medal (his fellow student Sergei Rachmaninov received the large gold medal).

In 1894 he met Mitrofan Beljajew , who became his publisher and patron. He organized his first guest performances abroad (1895/96), which soon made him known internationally. During his appearances, however, Scriabin played almost exclusively his own works.

In 1897 Scriabin married the concert pianist Vera Ivanovna Issakovich, who was committed to her husband's works and with whom he had four children, Rimma (1898–1905), Elena (1900–1990), Maria (1901–1989) and Lev (1902) -1910). From 1898 to 1903 Scriabin was a piano professor at the Moscow Conservatory. The material burden on his family, however, required an additional job as an inspector for music at the St. Catherine Institute in Moscow.

In November 1902 Scriabin met Tatjana de Schloezer, the sister of the musicologist and Scriabin researcher Boris de Schloezer . A little later she became his lover. In 1904 the long-awaited move abroad followed (Switzerland, Belgium, Italy, France). This was made possible by an annual pension of two million rubles, with which Margarita Kirillovna Morozova supported him from 1904 to 1908. In 1905 he separated from his wife Wera, who however refused to divorce him. Then Tatjana de Schloezer became the official wife at his side, with whom he had three children (Ariadna, Julian and Marina). Her son Julian Scriabin (1908–1919), who died early, pursued the same career as his father and left behind some compositions that stylistically come close to his father's late work. The daughter Ariadna Scriabina (1905-1944) became a poet and French resistance fighter in World War II . Scriabin's son-in-law, Vladimir Sofronitsky (1901–1961) was considered one of the most authentic Scriabin interpreters.

Scriabin's reputation abroad and in Russia began to grow, especially after the premiere of the Third Symphony on May 29, 1905 in Paris. The first performances of the 5th piano sonata in Moscow and the Poème de l'extase in New York (1906) marked the beginning of a “triumphal procession”. Of his numerous guest appearances, those in England in 1911 were of particular importance, since there he came into contact with English theosophists .

A few days after the New York premiere of the Promethée with light effects, Scriabin fell ill with blood poisoning , which he succumbed a little later. After his death, his second family remained destitute; however, she received diverse support from friends and musicians. Margarita Kirillowna Morozova also provided financial support to members of the family, and she financed the Scriabin Museum .

Music and influences

Innovations

Scriabin is considered an exceptionally good pianist, but as an adult he only played his own works in public. Furthermore, he composed music only for “his” instrument, the piano, and symphonic music.

In his early years his music was still very much oriented towards that of Frédéric Chopin and Franz Liszt , later he got to know Richard Wagner's music , but soon developed his tonal language beyond the chromaticism of Wagner's Tristan und Isolde . He followed a harmonic system that is no longer based on major-minor tonal ties, but on the use of a chord based on layers of fourths, the so-called " mystical chord " or "Prometheus chord" (the latter named after the orchestral work Promethée. Le Poème du feu, op. 60). The musicologist Zofia Lissa has described Scriabin's so-called sound center technique - an atonal composition technique - as a pre-form of the twelve-tone technique .

Furthermore, he further developed the piano sonata by making it one-movement. This development can be clearly seen in his sonatas. The four movements of the 1st sonata are already closely interwoven and aligned with the last; From the 5th sonata onwards , one-movement becomes the rule. The same principle of shifting to one movement also applies to his orchestral works.

Theosophy

Due to the illness of his right hand (overuse) in 1891 and a relapse in 1893, which almost led to a nervous breakdown, Scriabin began to have doubts about God and religion. A few years later he completely rejected the Orthodox faith. In 1903 he began to read more philosophical works and Greek myths and to cultivate close ties to theosophical circles (Scriabin was a member of the Theosophical Society Adyar in Belgium , which was headed by Jean Delville .)

The synesthete Scriabin

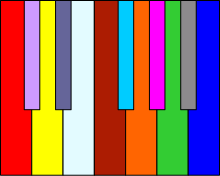

Music was no longer sufficient for the later Scriabin as an expression of his philosophical ideas. He was color synaesthetics ; H. For him, their sound was linked to specific color perceptions (see also the figure below). Scriabin reported to the English psychiatrist Charles S. Myers about his color impressions when playing music, which he compared with those of Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov and found many similarities. According to Myers, Scriabin's "hearing of colors" did not refer to single notes but to keys .

The score of his last completed orchestral work Prométhée. Le Poème du feu provides a separate part for a specially designed color piano. During his lifetime, the intended color effects were only partially feasible. For example, the Moscow chemist Alexander Moser constructed a light piano, which was presumably used in private previews of a piano version of the Promethée. Le Poème du feu was used in Scriabin's apartment. A model of this device has been preserved in the Scriabin Museum in Moscow. Only modern lighting technology of the second half of the 20th century made it possible to implement them adequately in individual performances.

The "Mystery"

Towards the end of his life he was more and more concerned with the idea of a multimedia “mystery”. This should appeal to all the senses as a symphony of word, tone, color, fragrance, touch, dance and moving architecture. This total work of art , which was supposed to represent a synthesis of all the arts and was of unseen proportions, he wanted to perform in India (India was the land of magic and mysticism for Scriabin) under a hemisphere with 2,000 participants until the whole of humanity was the so-called mystery and would have been brought into collective ecstasy. This, Scriabin believed, would have raised humanity to a higher level of consciousness, with himself as the messianic figure in their midst. Scriabin saw himself as a kind of messiah : he perceived his birth at Christmas as a sign of being chosen. His early death on Easter Tuesday was also understood symbolically by many. His work was also perceived as a prophecy of a threatening world cataclysm , which he witnessed with the outbreak of the First World War . However, blood poisoning due to an abscess on the upper lip in 1915 brought the mystery plans to an abrupt end. He was only able to draft the text and a few musical fragments before his death (later Alexander Nemtin undertook a reconstruction of the preparatory plot for the mystery from sketches of Scriabin ).

Overall, Scriabin's late work shows a stylistic development that - despite his short life - justifies a classification of Scriabin among the important innovators in music of the first decades of the 20th century.

Others

According to an occasional statement, Molotov , whose maiden name was Scriabin, was a nephew of Alexander Scriabin. Today this is considered refuted. An actual nephew of Scriabin was Anthony Bloom , because his mother Xenia was a half-sister of Alexander Scriabin.

Works

- 3 symphonies

- 3 symphonic poems

- Rêverie op. 24 (1898)

- Le Poème de l'Extase op.54

- Promethée. Le Poème du feu op. 60, which in view of the planned mystery requiresa so-called color piano with which the entire concert hall should be illuminated. This instrument is called “Luce” (Italian: light) in the score and is notated in two parts.

- Piano Concerto in F sharp minor op.20 (1896/97)

- In addition to 2 early sonatas, 10 piano sonatas with opus numbers , which are among the most important contributions of their genre. The sonatas 5–10 are in one movement (from No. 6 in a new harmonic system)

- Sonata No. 1 in F minor, Op. 6 (1892)

- Sonata No. 2 in G sharp minor, Op. 19 ("Sonate fantaisie") (1892–97)

- Sonata No. 3 in F sharp minor op.23 (1897/98)

- Sonata No. 4 in F sharp major op.30 (1903)

- Sonata No. 5 in F sharp major op.53 (1907)

- Sonata No. 6 op.62 (1911/12)

- Sonata No. 7 op. 64 ("White Mass") (1911)

- Sonata No. 8 op.66 (1912/13)

- Sonata No. 9 op. 68 ("Black Mass") (1911–13)

- Sonata No. 10 op.70 (1912/13)

- further piano works, mostly in miniature form and summarized in cycles

- Several series of preludes, including 24 preludes op. 11 (in accordance with strong Chopin)

-

Poèmes (genus developed by Scriabin), including:

- 2 Poèmes op.32 (No. 1 in F sharp major, No. 2 in D major) (1903)

- Vers la flamme , Poème op.72 (1914)

- 24 studies

Audio samples

In January 1910 Scriabin recorded 9 of his own works for Welte-Mignon :

- Prelude Op. 11, No. 1 *

- Prelude Op. 11, No. 2 *

- Mazurka Op. 40, No. 2 *

- Etude in D minor, op.8, no.12

Recordings of the piano sonatas (pianists)

- 1970 Ruth Laredo , 2 CDs Nonesuch (+ op. 2/1, 42, 57/1/2 and 72)

- 1971 Michael Ponti (as part of a GA of the piano works on 5 CDs at VoxBox)

- 1971 John Ogdon , 2 CDs EMI (+ op. 2/1, 48, 57, 58, 63, 67, 72 and 74)

- 1971 Igor Zhukov , LP

- 1971 Roberto Szidon , 2 CDs DG

- 1972–82 Vladimir Ashkenazy , 2 CDs Decca

- 1994–1997 Bernd Glemser , 2 CDs Naxos

- 1996 Håkon Austbø , 2 CDs Brilliant Classics

- 1989 Boris Berman , 2 CDs Music & Arts

- 1988–90 Robert Taub , 2 CDs harmonia mundi

- 1990 Burkard Schliessmann , 1 CD Bayer 100 161 (opp. 23, 68; + opp. 2/1, 8/12, 11, 16, 27, 37, 44/2, 51/2, 51/4, 73, 74 )

- 1995 Marc-André Hamelin , 2 CDs hyperion (+ op. 28 and op. Posth.)

- 1998 Evgeni Mikhailov , 2 CDs MEL CD 10 00638 © 1998 Scriabin State Memorial Museum

- 2000 Igor Shukow , 3 CDs Telos (+ op. 28)

- 2006 Michail Voskresensky , 2 CDs Classical Records

- 1997–2009 Yakov Kasman , 2 CDs Calliope

- 2004–07 Maria Lettberg (as part of a GA of the piano works on 8 CDs at capriccio)

- 2008? Vladimir Stoupel , 3 CDs audite

- 2008 Dmitri Alexeev , 2 CDs Brilliant Classics (2012)

- 2010 Anatol Ugorski , CAvi music

- 2010–16 Pervez Mody , Thorofon as part of a GA of all piano works still in progress (Sonatas No. 1 Op. 6 / No. 2 Op. 19 / No. 3 Op. 23 / No. 4 Op. 30 / No. 5 Op. 53 / No. 7 Op. 64 / No. 9 Op. 68 / No. 10 Op. 70)

- 2014 Anna Malikova , Acousence, 2 CDs, alternatively as Studio Master FLAC 96/24

- 2019 Vicenzo Maltempo , Complete Piano Sonatas, 2 CDs, Piano Classics PCL-10168, EAN / GTIN 5-029365-101684

literature

- Manfred Angerer : Musical aestheticism: analytical studies on Skrjabin's late work (= Viennese publications on musicology, 23), Schneider, Tutzing 1984. ISBN 3-7952-0412-7 .

- Sigfried Schibli: Alexander Scriabin and his music . Piper, Munich / Zurich, 1983. ISBN 3-492-02759-8 .

- Aleksandr Scriabin and the Scriabinists II . Music Concepts 37/38. Edited by Heinz-Klaus Metzger and Rainer Riehn . edition text + kritik , Munich 1984. ISBN 3-88377-171-6 .

- Marina Lobanova: Alexander Scriabin. Mystery and music. In: Das Orchester 5/1996, 2–7.

- Jonathan Powell: Skryabin [Scriabin], Aleksandr Nikolayevich. In: Grove Music Online (English; subscription required).

- Marina Lobanova: Scriabin, Aleksandr Nikolaevič. In: Ludwig Finscher (Hrsg.): The music in past and present . Second edition, personal section, volume 15 (Schoof - Stranz). Bärenreiter / Metzler, Kassel et al. 2006, ISBN 3-7618-1135-7 , Sp. 883–899 ( online edition , subscription required for full access)

- Hanns-Werner Heister and Walter-Wolfgang Sparrer (eds.): Contemporary composers . edition text + kritik, Munich 2016.

- Marina Lobanova: magician and theurg. The musical ideas of the composer Alexander Scriabin . In: NZfM 6/2004, 28-33.

- Marina Lobanova: Mystic • Magician • Theosophist • Theurgist. Alexander Scriabin and his time. 2004, 2nd edition by Bockel Verlag, Neumünster 2015, ISBN 978-3-95675-001-4 .

- Igor Fjodorowitsch Belsa: Alexander Nikolajewitsch Scriabin . New Music, Berlin 1986.

- Leonid Leonidowitsch Sabanejew : Memories of Alexander Scriabin. Ernst Kuhn, Berlin 2005. ISBN 3-928864-21-1 .

- Leonid Leonidowitsch Sabanejew: Alexander Scriabin. Work and world of thought. Ernst Kuhn, Berlin 2006. ISBN 3-936637-06-7 .

- Boris de Schloezer : Alexander Scriabin on his way to the mystery . In: Ernst Kuhn (Ed.): Studia slavica musicologica . tape 48 . Ernst Kuhn, Berlin 2012, ISBN 978-3-936637-21-2 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ The AN Scriabin Memorial Museum (accessed July 9, 2017).

- ↑ Fashionable Occultism: The World of Russian Composer Aleksandr Scriabin ( Memento from December 1, 2006 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Theosophical Society in America ( Memento of May 30, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Charles S. Myers: Two Cases of Synesthesia. The British Journal of Psychology, Vol. VII, 1914-15, Cambridge, pp. 112-117. German Translation by Christoph Hellmundt in: Christoph Hellmundt (Ed.): Alexander Skrjabin. Letters . Philipp Reclam jun., Leipzig, 1988, ISBN 3-379-00360-3 , pp. 388-390.

- ↑ About heralds and heretics. Biographical studies on the music of the 20th century . Böhlau, Vienna 1986. ISBN 3-205-05014-2

- ↑ Simon Sebag-Montefiore : At the court of the red tsar . Frankfurt / Main 2006.

- ↑ latimes.com

- ^ The Independent, obituary, Aug. 9, 2003

- ↑ Complete directory see List of Compositions

Web links

- Works by and about Alexander Nikolajewitsch Skrjabin in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Alexander Nikolajewitsch Skrjabin in the German Digital Library

- Sheet music and audio files by Alexander Nikolaevich Scriabin in the International Music Score Library Project

- Scriabin catalog raisonné at russisches-musikarchiv.de

- Alexander Scriabin ( Memento from July 16, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Download free sheet music for piano

- Jörg-Peter Mittmann: Crossing borders. Notes on the harmonic analysis of the works of Alexander Scriabin (PDF, 220 kB)

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Scriabin, Alexander Nikolayevich |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Скрябин, Александр Николаевич (Russian); Scriabin, Aleksandr Nikolaevič; Scriabin, Aleksandr Nikolaevič (scientific transliteration) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Russian pianist and composer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | January 6, 1872 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Moscow |

| DATE OF DEATH | April 27, 1915 |

| Place of death | Moscow |