Mystical chord

Mystical chord is a "theosophically transfigured" term that goes back to Leonid Sabanejew for a chord used by Alexander Scriabin , which is particularly evident in his orchestral work " Prométhée. Le Poème du feu ”op. 60 ( “ Prometheus - The Poème des Feuers ” ) (1911) became famous and is therefore also known as the “ Promethean chord ” .

The chord allows for different interpretations:

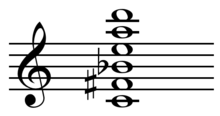

- as a fourth chord , which is made up of two pure, two augmented and one diminished fourth . Because of the diminished fourth f sharp b-flat, which sounds the same with a major third when the tuning is equal , it is "not, however, a real fourth chord".

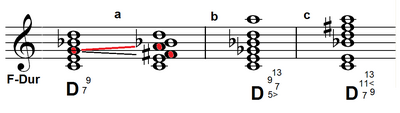

- as a dominant seventh chord with a double lead to the fifth (see above note example a): The fifth g 'is replaced by f sharp' and a '. In the adjacent example from Scriabin's Scherzo op. 46, these two tones a 'and f sharp' dissolve into the fifth g '.

- as a dominant tredezima chord with missing undecimal and deeply altered fifth, whereby the f sharp 'enharmonic was changed to g flat' (note example b). The dominant character is particularly underlined by the leading note, leading down to the f ' . Alternatively, the chord is sometimes seen as a dominant sixth-nonchord with a deeply aged fifth to which a sixth is added as a tone foreign to the harmony.

- as a "synthetic chord" formed from the tones of the acoustic scale . The latter represents the tones 8 to 14 of the overtone series , even if only very imperfectly due to the “translation” into the equal tuning . The idea of associating the mystical chord with the overtone series did not come from - as is often claimed - from Scriabin himself, but from his friend Leonid Sabaneev .

- as a dominant tredezima chord with a missing fifth and an older undecimal (# 11) (note example c). This interpretation represents Zsolt Gárdonyi and referred the chord because of its relationship to the acoustic scale as "acoustic Tredezimakkord " . He rejects the widespread interpretation as a fourth chord on the grounds that it is related to a "curricular deficit problem in professional music training" in which the occupation with wide registers hardly goes beyond that of four-note chords. Today, however, we know that wide ranges can occur not only with three and four notes, but of course also with five, six and seven notes. The lack of the fifth and the wide form of application did not change anything in the basic structure of the third layered structure of the acoustic seven notes, just like with classical seventh chords, which can be recognized as such even with an occasional missing fifth and also in a wide range.

The acoustic seven-tone, which occurs in various ways in French Impressionism (e.g. in the basic position and in the most varied of inversions, narrow or wide, complete or incomplete, figured or unfigured) is also used by Scriabin in earlier works, e.g. B. in the first movement of the Piano Sonata op. 30 (1903) or in the Scherzo op. 46. The sensation that he caused in Scriabin's works around and after op. 60 is based on a use that negates its functional origin. Scriabin, in whose compositional development an increasingly dissonant tendency could be observed anyway, gradually began to “freeze” altered leading chords of a dominant character, which leads to the dominant losing its original character and rather becoming the center of sound.

Op 9 in the final bars of the 7th Klaviersonate. 64 (1911/12), the clay material (fis-his-e uses only from the 6 tones of the Mystic by fis transposed chord together 1 -ais 1 -dis 2 -GIS 2 ), its horizontal as well as vertical use almost seems like an anticipation of the twelve-tone technique . But with Scriabin the interval structure of a chord determines the horizontal and vertical tone combinations, while with Schönberg the interval structure of a series takes on this task. In his later days Scriabin also used other "synthetic chords" .

literature

- Gárdonyi-Nordhoff: Harmonics. Wolfenbüttel 2002, p. 180 ff. ISBN 3-7877-3035-4

References and comments

- ↑ a b c Mystical chord In: Marc Honegger, Günther Massenkeil (Hrsg.): The great lexicon of music. Volume 5: Köth - Mystical Chord. Updated special edition. Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau a. a. 1987, ISBN 3-451-20948-9 , p. 446.

- ↑ a b c Mystical chord In: Willibald Gurlitt , Hans Heinrich Eggebrecht (Hrsg.): Riemann Musik Lexikon (subject part) . B. Schott's Sons, Mainz 1967, p. 620 .

- ↑ a b Reinhard Amon: Lexicon of the theory of harmony . 2nd Edition. Doblinger, Vienna 2015, ISBN 978-3-902667-56-4 , pp. 17 .

- ^ A b Everard Sigal: Tonsatz, Dominanten , online . Retrieved October 5, 2015.

- ↑ Zsolt Gárdonyi : Alexander Skrjabin (1871-1915), on the 100th anniversary of his death . Würzburg, 2015, p. 2