osteoporosis

| Classification according to ICD-10 | |

|---|---|

| M80.- | Osteoporosis with a pathological fracture |

| M81.- | Osteoporosis without a pathological fracture |

| M82.- | Osteoporosis in Diseases Classified Elsewhere |

| ICD-10 online (WHO version 2019) | |

The osteoporosis (from ancient Greek ὀστέον Osteon , German , bone ' and πόρος poros , ford, Pore') is a disorder in bone metabolism and a common age-related disease of the bone that it (often associated with a calcium deficiency) thinner and more porous and therefore susceptible to Makes breaks (fractures). Calcium is an important mineral for organisms; the human body contains about 1 kg of it. It is important here that this element ensures the development and maintenance of the bone tissue.

The disease , also known as bone loss , is characterized by a decrease in bone density as a result of a breakdown of bone tissue that exceeds the build-up as part of natural bone remodeling . Due to the higher turnover rate, the cancellous bone is typically more affected than the cortex , which is reflected in the sites of predilection for bone fractures; however, the increased susceptibility to fractures can affect the entire skeleton .

Osteoporosis, which was first described in 1885 by the Innsbruck pathologist Gustav Adolf Pommer (1851-1935), is the most common bone disease in old age. The most common (95 percent) is primary osteoporosis; In contrast to secondary osteoporosis, this does not occur as a result of another disease. 80 percent of all osteoporoses affect women after the menopause (see postmenopause ), with small-bony northern Europeans and smokers being particularly affected. 30% of all women develop clinically relevant osteoporosis after menopause. Secondary osteoporoses are less common (5%), with diseases that require treatment with glucocorticoids for a longer period of time and / or lead to immobilization being in the foreground.

causes

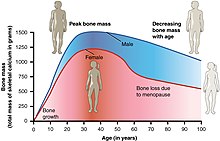

The bone mass increases in the first three decades of life (bone is built up in youth), then reaches a peak and slowly decreases again in the later years of life. Osteoporosis usually arises from inadequate bone formation at a young age and / or accelerated breakdown later. Causes for this can be:

- Primary osteoporosis (95%):

- Idiopathic juvenile osteoporosis in young people

- Postmenopausal osteoporosis (type I osteoporosis)

- Senile osteoporosis (type II osteoporosis)

- Secondary osteoporosis (5%):

- Hormonal: hypercortisolism ( Cushing's syndrome ), hypogonadism , hyperparathyroidism , hyperthyroidism , pregnancy-associated osteoporosis

- Gastroenterological causes: malnutrition , anorexia nervosa (anorexia), malabsorption , renal osteopathy

- Metabolic diseases such as cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis

- Immobilization (restricted movement)

- Medicinal:

- Long-term therapy with corticosteroids ( cortisol ) works like Cushing's syndrome

- Long-term therapy with heparin (to prevent blood clotting)

- Vitamin K antagonists as anticoagulants such as phenprocoumon (Marcumar) reduce bone density, since vitamin K is necessary for the maturation of the bone matrix. However, there is no evidence that the intake of vitamin K has any effect on bone density or the risk of fractures.

- Stomach acid blocking drugs

- High-dose therapy with thyroid hormones reduces bone density just like hyperthyroidism.

- Gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonists, if taken for over a year, almost completely inhibit the formation of estrogen in the ovaries

- Aromatase inhibitors also inhibit the formation of estrogen.

- Cytostatics

- Laxative abuse and long-term therapy with cholestyramine reduce the absorption of vitamin D in the digestive tract.

- Lithium can lead to increased parathyroid hormone levels and thus trigger osteoporosis.

- Cases of osteoporosis up to fractures have been reported with long-term use of anticonvulsants . The Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices has had the specialist information for certain drugs revised accordingly .

- Hereditary:

- Neoplastic diseases:

- Monoclonal gammopathies (including monoclonal gammopathy of unclear significance or multiple myeloma )

- Mastocytosis

- Myeloproliferative Diseases

- Inflammation :

- Other causes:

- Pernicious anemia , vitamin B12 deficiency

- Folic acid deficiency

- Underweight

- Meat-rich, vegetables / fruit-poor diet seems to be unfavorable. Among other things, a connection between the bone metabolism and the acid-base balance was suspected, but this has not been proven.

- Consumption of phosphate-containing cola beverages could pose a risk, but heavy cola consumption correlates with a low-calcium diet

Diagnosis

anamnese

The medical history shows back pain as the main symptom of osteoporotic vertebral body fractures, a reduction in body size due to sintering of the vertebral bodies and kyphosis / scoliosis of the spine, fractures of the femoral neck and distal radius. In addition, there is the acquisition of the above. Risk factors for osteoporosis, especially a low-calcium diet, early menopause and familial stress, as well as evidence of other systemic bone diseases.

Clinical examination

As part of the clinical examination, body height is measured (compared to previous results or information), kyphosis of the thoracic spine or scoliosis of the lumbar spine, typical skin folds on the back ("Christmas tree phenomenon") and a reduction in the distance between the ribs and Iliac crest.

roentgen

An X-ray examination of the thoracic and lumbar spine reveals fractures and decreases in height. Bone fractures due to osteoporosis according to their frequency:

- Vertebral body collapses ( sintering , compression fractures ),

- Femur fractures near the hip joint (including femoral neck fractures ),

- Spoke fractures near the wrist ( distal radius fractures ),

- Humerus fractures (subcapital humerus fractures)

- Pelvic fractures .

Biomarkers

Biomarkers such as the increased excretion of C-telopeptides of type I [collagen] in the urine can be used for the diagnosis of osteoporosis and osteoarthritis as well as for assessing the current course of the disease.

Anton Eisenhauer, physicist at Geomar in Kiel, and colleagues developed a non-invasive, sensitive diagnostic method that shows bone loss at an early stage. As a biomarker, the method measures the calcium concentration in blood and urine, namely the ratio between its isotopes 42Ca and 44Ca. (The Ca isotope with atomic weight 42 is lighter than the 44.) As soon as the 42Ca increases significantly compared to the 44Ca in the fluids, the bone tissue loses its characteristic 42Ca isotope. This finding marks the beginning of osteoporosis. The person can now be treated years earlier than the standard diagnosis, which is based on the measurement of X-ray absorption (dual-energy X-rayabsorptiometry, DEX).

Bone density

Under the BMD (bone mineral density also, English density Bone, bone mineral density (BMD) ) is defined as the ratio of mineralized bone to a defined volume of bone.

Bone density measurement

With the bone density measurement (osteodensitometry) the so-called T-value is determined. This is a statistical value that enables a comparison of the measured bone density value with the population of young adult women and a statement about the risk of fracture. To measure the bone mineral density (BMD - English bone mineral density ), various methods are available:

The most common is the dual-X-ray absorptiometry (DXA or DEXA - English dual-energy-x-ray-absorptiometry ). The WHO definition is based on it and the T-value is determined with its help. Another method is quantitative computed tomography ( QCT or pQCT ). The measurement of bone density by means of ultrasound, i.e. with so-called quantitative ultrasound (QUS), is highly controversial and only in very few cases is meaningful. The informative value for DXA and QCT, however, is well documented. The measurement of bone density for early detection is not a service provided by the statutory health insurance funds . The insured person has to pay for it himself if there is no bone fracture without the appropriate force (a so-called fatigue fracture) with suspected osteoporosis before the measurement.

However, bone density itself is only partially responsible for the increased risk of bone breakage in osteoporosis; the breaking strength is mainly determined by the outer compacta layer, while the bone density measurement mainly measures the trabecular bone.

Based on a bone density measurement, the computer-based algorithm FRAX ( WHO Fracture Risk Assessment Tool ) can be used to determine the probability of suffering an osteoporotic fracture in the following ten years. This is particularly suitable for assessing the need for antiresorptive therapy in osteopenia .

Particularly in older people, frequent sources of error in the DXA measurement on the lumbar spine should be taken into account with the concealment of a reduced or even simulated higher bone density: through sintering of vertebral bodies, scoliosis, spondylophytes or hardening of the arteries (aortosclerosis). For a usable result at least two vertebral bodies must be assessable.

If osteoporotic fractures have already been detected in the X-ray or a pertrochanteric femur fracture has occurred, the diagnosis of osteoporosis can be made and appropriate therapy initiated without a previous DXA measurement.

Screening

The umbrella organization for osteology recommends basic diagnostics for women after the menopause and for men over 60 years of age, if so

- fractures have already occurred that were caused by the application of weak force,

- There are basic diseases that can affect the bones or

- Risk factors for vertebral body fractures or hip fractures are present (DVO risk model 2006).

Differential diagnosis

Other diseases that are primarily associated with deteriorated bone quality are:

- the osteomalacia

- the hypophosphatasia (HPP). This occurs less often than osteoporosis. Some forms of hypophosphatasia do not become symptomatic until adulthood and could lead to the misdiagnosis of osteoporosis. Decreased serum alkaline phosphatase activity , early loss of milk teeth and the occurrence of atypical fractures (e.g. subtrochanteric lateral femoral fracture ) with delayed fracture healing indicate HPP. It is important to differentiate between osteoporosis and HPP, since the administration of bisphosphonates is contraindicated in HPP .

Course of the disease and prognosis

Osteoporosis is an initially imperceptible disease, but in the case of bone fractures, especially in the elderly, it means a high level of disease (pain, bed restraint, sometimes permanent immobilization ).

A distinction is made between primary and secondary osteoporosis. The much more common primary osteoporosis includes postmenopausal (or postmenopausal ) osteoporosis and geriatric osteoporosis (involution osteoporosis). Secondary osteoporosis occurs, among other things, as a result of metabolic diseases or hormonal disorders.

It is assumed that around 30% of all women in Germany develop primary osteoporosis after menopause . Age osteoporosis is an equally common clinical picture for men from the age of 70. Typical features of osteoporosis are a decrease in bone mass and deterioration in bone architecture and, as a result, a decrease in bone stability. This leads to an increased risk of bone deformities ( fish vertebrae ) and bone fractures . Bone fractures in osteoporosis are particularly found in the vertebrae , the thigh neck and the wrist . The healing of fractures in osteoporosis is not disturbed, the time frame is the same as for people who are not ill. The consequences of the fractures can, however, be lasting, especially in the elderly, and can lead to death through secondary diseases such as pneumonia or pulmonary embolism .

Treatment options and prevention

Way of life

Physical activity protects against bone loss. The forces that act on the bone stimulate the bone-building cells to form new bone substance. Weight-bearing endurance exercises and muscle-building training, as well as aerobics, are mainly recommended . Sufficient exposure to sunlight also promotes vitamin D production in the skin , at least half an hour a day is recommended .

nutrition

The DVO recommends an intake of 1000 to a maximum of 2000 mg calcium per day with the food as basic therapy for osteoporosis patients without specific medicinal osteoporosis therapy. This does not apply to children, adolescents, premenopausal women and men up to the age of 60. One gram of calcium is contained in one liter of milk or 100 g of hard cheese. In addition to dairy products (especially milk and yoghurt), green vegetables such as kale and broccoli as well as seeds and nuts are very good sources of calcium. People with lactose intolerance can choose alternatives to lactose-free dairy products, hard cheese , sugar-free cereal milk and mineral water . When consuming mineral water, a calcium content of over 150 mg per liter must be ensured.

If the recommended intake of calcium cannot be achieved with a balanced diet, supplementation, e.g. in tablet form, can be carried out. The international guidelines recommend combined intake with vitamin D (ergolecalciferol and cholecalciferol , but not metabolites such as 1-alpha or 1,25-dihydroxy vitamin D) as part of the basic therapy .

Heavy alcohol and tobacco consumption should be avoided.

Although vitamin K is required for the maturation of the bone matrix and the risk of osteoporosis increases with long-term use of vitamin K antagonists such as Marcumar , there is no evidence that the intake of vitamin K has a positive effect. There is also no qualitative study in this regard. While all of the evidence-based guidelines recommend vitamin D and calcium, there is no recommendation for vitamin K intake.

Pharmacotherapy

According to the DVO guidelines , taking into account bone density , age, past vertebral body fractures and other risk factors, the following drug therapy is recommended:

- Bisphosphonates ( alendronic acid , ibandronic acid , risedronic acid, and zoledronic acid ): standard therapy, inhibit bone resorption

- Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators (SERM): Raloxifene (only to prevent vertebral body fractures). Also inhibit bone resorption

or

- Parathyroid hormone and its analogue teriparatide

- Strontium ranelate : Bone density measurements show higher values due to the storage of strontium , but this is not relevant for the assessment of the course in practice.

The bone marker β-CrossLaps can be used to monitor anti-resorptive osteoporosis therapy .

Also in use, but not recommended by DVO

- Calcitonin , hardly used anymore, the benefits are poorly documented. In addition, severe allergy symptoms tend to occur during treatment.

- STH (growth hormone), no benefit proven; possibly problematic side effects.

- Fluoride (outdated; develop hard but brittle bones, stability does not improve)

- Since the criticism of hormone replacement therapy, oestrogens have only been used to a limited extent for this indication due to side effects , but are mostly used in postmenopausal women (in a form coupled to sulfur or glucuronic acid ) with regard to osteoporosis prevention and treatment (slowing down bone loss) with sufficient calcium administration , effective. The decision for or against must be made individually.

- Vitamin D metabolites such as 1-alpha or 1,25-dihydroxy vitamin D (benefit in postmenopausal osteoporosis not clearly proven, expensive, problematic side effects; 1,25 vitamin D (calcitriol) is effective and indicated for certain bone diseases in the Advanced kidney disease).

Denosumab represents a new osteoporosis treatment option. It is a monoclonal antibody that is administered as an injection under the skin once every six months. On May 28, 2010, denosumab (with the trade name Prolia) was approved for all 27 member states of the European Union (EU) as well as in Norway, Iceland and Liechtenstein for the treatment of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women with an increased risk of fractures and for the treatment of bone density loss through hormone-ablative therapy ( Androgen deprivation) in men with prostate cancer and an increased risk of fractures.

Daily use of an ointment containing nitroglycerin increased bone density significantly in a study by Canadian researchers. However, it has not been proven whether this reduces the risk of bone fractures. The effect is explained by the release of nitric oxide , which directly inhibits the osteoclasts .

The example of fluorides , which can increase the risk of fracture ( fluorosis ) , shows that an increase in bone density does not have to go hand in hand with a reduced risk of fracture, but can actually increase it . It is therefore essential to carry out studies for new osteoporosis remedies which demonstrate a reduction in the risk of breakage and which must not be inferior in effectiveness to the remedies that are already known.

There are no studies that compare the existing bisphosphonates with one another, which is why a general recommendation regarding a specific active ingredient cannot yet be made. Depending on the location of the fractures, the risk could be reduced by 25 to 70%. Bisphosphonates harbor the rare risk of atypical fractures of the femur and osteonecrosis of the jawbone. If there is little benefit over a treatment period of three to five years, the treatment with these drugs can be discontinued or changed with regard to the side effects.

Prevention of breaks

Hip protectors

Hip protectors are used to prevent osteoporotic femoral neck fractures . A 2014 Cochrane review found that hip protectors can reduce the risk of femoral neck fractures in the elderly. The low acceptance and use of the protectors limits their prophylactic value.

There are also various alternative medicine methods for the prevention or supportive treatment of osteoporosis . However, the treatment costs of these procedures are not covered by the statutory health insurance .

Basic nutrition

A recommendation, which is neither scientifically proven nor mentioned in the guidelines, is the so-called alkaline diet or the intake of so-called base salt mixtures. According to supporters of this treatment method, an alleged over-acidification of the body should lead to increased bone loss, since basic calcium salts (the existence of which is scientifically undisputed) would be dissolved from the bone tissue to neutralize the acid (like the lime from an eggshell in a vinegar bath). In this theory, however, the much more important buffer systems of the blood buffer are neglected. No coffee beans, black tea, alcohol, cola and lemonade beverages, animal protein (meat, sausage, fish), fast food and ready meals, most dairy products, industrial sugar, sweeteners, sweets, white flour and white flour products, peanuts, Brazil nuts, etc. recommended and an acid-inhibiting or base-forming food prescribed, consisting for example of vegetable and fruit juices, herbal tea, vegetables and leaf salads as well as fruits. The rules according to which a food is to be divided into acidic or basic are not always directly understandable, for example coffee does not have an acidic effect in the blood, but weakly basic.

A base-rich diet is therefore particularly beneficial for a healthy bone metabolism. While there is no research showing a decrease in bone fracture rates or an increase in bone density, it is argued that studies have shown that a protein and meat-rich diet promotes calcium breakdown from the bones and calcium excretion via the kidneys. In these studies, however, not a word is spoken of an acid- or base-forming diet.

Another statement of the basic nutritional theory is that an acid-rich diet leads not only in the sick but also in the healthy organism to a systematic overacidification , which increases with age with decreasing kidney function. However, this postulated acidification can not be measured in the blood as part of a blood gas analysis . Acidification of the urine is primarily just a sign that the blood buffers and the kidneys are doing their job and are excreting acids.

With increasing acidity, the body's buffer reserves are exhausted and mineral deposits in the bones are increasingly attacked. In addition, in an acidic environment, the body increasingly releases inflammation-promoting proteins such as NF-κB , TNF-α and COX-2 , which accelerate bone breakdown. However, this acidification is not found in a healthy organism with regular food intake, but with a significant restriction in the function of the blood buffer and the excretory function of the kidneys.

In order to counteract the loss of bone substance, so-called basic substances such as potassium citrate are recommended. Clinical studies have shown that potassium citrate counteracts calcium loss via the kidneys and calcium breakdown from the bones. A prospective controlled intervention study in 161 postmenopausal women with osteopenia showed that partial neutralization of diet-induced acid exposure (using 30 mmol potassium citrate per day, equivalent to 1.173 g potassium) over a period of twelve months significantly increased bone density and significantly improved bone structure. Potassium citrate is just as effective as raloxifene , an estrogen receptor modulator used in the treatment and prevention of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. The potassium citrate should be supplied with the bone minerals calcium and magnesium as well as vitamin D , because the magnesium content in the bones is reduced just as much as that of calcium, according to basic theory.

Physical procedures

- Magnetic field therapy : pulsating electromagnetic fields are intended to stimulate bone formation.

- Vibration training - also biomechanical stimulation (BMS): it was originally developed to treat Russian cosmonauts: The person to be treated stands on a plate that vibrates in a frequency range of 20 to about 50 Hz and causes muscle contractions through the stretch reflex . The forces that arise are intended to stimulate the bone to grow ( Mechanostat ).

economic aspects

With about 2.5 to 3 billion euros annually in direct and indirect illness costs in Germany, osteoporosis also has a great economic weight. That is why it was put on the list of the ten most important diseases by the World Health Organization (WHO).

Critics argue that the re-evaluation of osteoporosis in the 1990s was controlled by the pharmaceutical industry and the manufacturers of diagnostics who want to create a market for new diagnostic devices and drugs ( disease mongering ). On the other hand, it has only been possible to reliably measure bone density since around 1985. Only since then has it been possible at all to adequately assess the clinical picture before the occurrence of bone fractures, to treat it preventively and to prevent fractures.

See also

- Transient osteoporosis

- Expert standard fall prevention in professional care

- World Osteoporosis Day

literature

- Tara Coughlan, Frances Dockery: Osteoporosis and fracture risk in older people. In: Clin Med (Lond) 14, 2, 2014: 187-191. PDF.

- Adele L Boskey, Robert Coleman: Aging and bone. In: J Dent Res 89, 12, 2010: 1333-1348. PDF.

- Walter Siegenthaler , Hubert E. Blum: Clinical pathophysiology . 9th, completely revised edition. Georg Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart a. a. 2006, ISBN 3-13-449609-7 .

- Osteoporosis information . Austrian Medical Association, Vienna 2007; Leaflet.

- Beat Seiler: Health policy program for adequate osteoporosis care . (= Series of publications of the SGGP. 85). Verlag Swiss Society for Health Policy SGGP, Zurich 2006, ISBN 3-85707-85-4 .

Historical literature

- Lois Jovanovic, Genell J. Subak-Sharpe: Hormones. The medical manual for women. (Original edition: Hormones. The Woman's Answerbook. Atheneum, New York 1987) From the American by Margaret Auer, Kabel, Hamburg 1989, ISBN 3-8225-0100-X , pp. 214–222 and 383.

- Ludwig Weissbecker: disorders in bone metabolism. In: Ludwig Heilmeyer (ed.): Textbook of internal medicine. Springer-Verlag, Berlin / Göttingen / Heidelberg 1955; 2nd edition ibid. 1961, pp. 1123-1129, here: pp. 1126 f. ( The osteoporosis ).

Web links

- Anton Eisenhauer: Recognize bone loss early. Video from ARD-alpha, August 17, 2020.

- Biography Gustav-Adolf Pommer (1851–1935), the first person to describe osteoporosis.

Organizations

- Scientific umbrella organization for osteology (DVO) / S3 guidelines for osteoporosis

- www.osteoporose.org - Bone Health Board of Trustees

- www.netzwerk-osteoporose.de (NWO) - Netzwerk-Osteoporose - non-profit organization for patient competence e. V. for the nationwide promotion of self-help, rehabilitation sport, functional training and the organizational structures in osteoporosis self-help.

- International Osteoporosis Foundation

- German Rheumatism League

information

- S3- guideline prophylaxis, diagnosis and therapy of osteoporosis of the German-speaking Scientific Osteological Societies (umbrella organization of the German-speaking Scientific Osteological Societies). In: AWMF online (as of December 2017)

- Erika Baum, Klaus M. Peters: Primary osteoporosis - guideline-based diagnostics and therapy . In: Dtsch Arztebl . No. 105 (33) , 2008, pp. 573-582 ( review ).

- DVO guideline osteoporosis 2017. umbrella organization osteology, January 26, 2018.

- DVO guideline osteoporosis 2014. (historical). (No longer available online.) Umbrella Association Osteologie, November 13, 2014, archived from the original on May 25, 2018 .

- Osteoporosis Patient Guideline 2010 (PDF; 1 MB) (historical). (No longer available online.) Umbrella association of German-speaking osteoporosis self-help associations and patient-oriented osteoporosis organizations e. V. (DOP) Germany, Austria, Switzerland, 2009, archived from the original on September 9, 2015 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Horst Kremling : Historical considerations on preventive medicine. In: Würzburg medical history reports 24, 2005, p. 244.

- ↑ Berginer et al .: Chronic Diarrhea and Juvenile Cataracts: Think Cerebrotendinous Xanthomatosis and Treat. In: Pediatrics . No. 123 (1): 143-7 , 2009, doi : 10.1542 / peds.2008-0192 ( aappublications.org ).

- ↑ Mignarri et al .: A suspicion index for early diagnosis and treatment of cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis. In: J Inherit Metab Dis. No. 37 (3): 421-9 , 2014, doi : 10.1007 / s10545-013-9674-3 ( wiley.com ).

- ↑ MJ Seibel, H. Stracke: Metabolic Osteopathies . Schattauer-Verlag, Stuttgart 1997, ISBN 3-7945-1635-4 .

- ↑ Y. Sato et al. a .: Long-term Oral Anticoagulation Reduces Bone Mass in Patients with Previous Hemispheric Infarction and Nonrheumatic Atrial Fibrillation. In: Stroke. 28, 1997, pp. 2390-2394.

- ↑ Lack of gastric acid affects calcium absorption. ( Memento from May 7, 2010 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Antiepileptic drugs and bone diseases (PDF, 60 kB). Announcement of the BfArM of January 9, 2013.

- ↑ A. Prentice: Diet, nutrition and the prevention of osteoporosis . In: Public Health Nutrition. 2004 (7), pp. 227-243.

- ↑ KL Tucker u. a .: Framingham Osteoporosis Study: Colas, but not other carbonated beverages, are associated with low bone mineral density in older women . In: American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2006 (84), pp. 936-942.

- ↑ Pierre Meunier: Osteoporosis: Diagnosis and Management . Taylor and Francis, London 1998, ISBN 1-85317-412-2 .

- ↑ M. Skarpellini et al. a .: Biomarkers, type II collagen, glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate in osteoarthritis follow-up: the "Magenta osteoarthritis study". In: Journal of orthopedics and traumatology official journal of the Italian Society of Orthopedics and Traumatology. 2008, pp. 81-87.

- ^ Anton Eisenhauer, M Müller, Alexander Heuser, A Kolevica, CC Glüer, M Both, C Laue, UV Hehn, S Kloth, R Shroff, Jürgen Schrezenmeir: Calcium isotope ratios in blood and urine: A new biomarker for the diagnosis of osteoporosis . In: Bone Rep 10, 2019: 100200. PDF.

- ↑ G. Holzer u. a .: Hip fractures and the contribution of cortical versus trabecular bone to femoral neck strength. In: J Bone Miner Res . 24, 2009, pp. 468-474. doi: 10.1359 / jbmr.081108

- ↑ A. Unnanuntana, BP Gladnick, E. Donnelly, JM Lane: The assessment of fracture risk. In: J Bone Joint Surg Am . 92-A, 2010, pp. 743-753.

- ↑ Walter Behringer, Joachim Zeeh: diagnosis and treatment of osteoporosis. In: Ärzteblatt Thuringia. 23, 2012, pp. 275-276.

- ↑ Walter Behringer, Joachim Zeeh: diagnosis and treatment of osteoporosis. In: Ärzteblatt Thuringia. 23, 2012, p. 276.

- ^ S3 guideline of the umbrella organization of the German-speaking Scientific Osteological Societies e. V. ( Memento of the original from November 21, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF)

- ↑ a b c T. Schmidt, M. Amling, F. Barvencik: Hypophosphatasie . In: The internist . tape 57 , no. 12 , October 28, 2016, ISSN 0020-9554 , p. 1145-1154 , doi : 10.1007 / s00108-016-0147-2 .

- ↑ J. Body et al. a .: Non-pharmacological management of osteoporosis: a consensus of the Belgian Bone Club . In: Osteoporos Int . tape 22 , no. 11 , 2011, p. 2769-2788 , doi : 10.1007 / s00198-011-1545-x .

- ↑ D. Bonaiuti et al. a .: Exercise for preventing and treating osteoporosis in postmenopausal women . In: Cochrane Database Syst Rev . tape 3 , doi : 10.1002 / 14651858.CD000333 .

- ↑ a b Prophylaxis, diagnosis and therapy of osteoporosis in adults. (PDF) DVO Guideline Osteoporosis 2014.

- ^ S3 guideline of the umbrella organization of the German-speaking Scientific Osteological Societies e. V. 2017 ( Memento of the original from April 17, 2018 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF).

- ^ S. Sahni, KL Tucker, DP Kiel, L. Quach, VA Casey, MT Hannan: Milk and yogurt consumption are linked with higher bone mineral density but not with hip fracture: the Framingham Offspring Study. In: Archives of Osteoporosis. February 2013, 8, p. 119.

- ↑ World Osteoporosis Day October 20: Active prevention of osteoporosis , October 19, 2018, accessed on May 14, 2019 in Uniqagroup.com.

- ↑ Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline No. 71, 2003 ( Memento from January 15, 2014 in the web archive archive.today )

- ↑ Guideline of the National Osteoporosis Foundation (USA), 2003 ( Memento of the original from December 22, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ CJ Rosen: Postmenopausal osteoporosis. In: New England Journal of Medicine . 353, 2005, pp. 595-603.

- ^ Ian R. Reid, Anne M. Horne, Borislav Mihov, Angela Stewart, Elizabeth Garratt: Fracture Prevention with Zoledronate in Older Women with Osteopenia . In: New England Journal of Medicine . tape 379 , no. 25 , December 20, 2018, ISSN 0028-4793 , p. 2407-2416 , doi : 10.1056 / NEJMoa1808082 ( nejm.org [accessed February 26, 2019]).

- ↑ Lois Jovanovic, Genell J. Subak-Sharpe: Hormones. The medical manual for women. (Original edition: Hormones. The Woman's Answerbook. Atheneum, New York 1987) From the American by Margaret Auer, Kabel, Hamburg 1989, ISBN 3-8225-0100-X , 382.

- ↑ Prolia (denosumab) Granted Marketing Authorization in the European Union. Press release. May 28, 2010.

- ↑ prolia.de website for specialist groups

- ↑ Effect of Nitroglycerin Ointment on Bone Density and Strength in Postmenopausal Women: A Randomized Trial. In: Journal of the American Medical Association . 305 (8), 2011, pp. 800-807.

- ↑ a b c J. J. Body: How to manage postmenopausal osteoporosis? In: Acta Clin Belg . tape 66 , no. 6 , 2011, p. 443-447 , doi : 10.1179 / ACB.66.6.2062612 .

- ↑ E. Suresh, M. Pazianas, B. Abrahamsen: Safety issues with bisphosphonate therapy for osteoporosis . In: Rheumatology (Oxford, England) . tape 53 , no. 1 , 2014, p. 19-31 , doi : 10.1093 / rheumatology / ket236 .

- ↑ M. Whitaker, J. Guo, T. Kehoe, G. Benson: Bisphosphonates for osteoporosis - where do we go from here? In: N. Engl. J. Med. Band 366 , no. 22 , 2012, p. 2048-2051 , doi : 10.1056 / NEJMp1202619 .

- ↑ N. Santesso, A. Carrasco-Labra, R. Brignardello-Petersen: Hip protectors for preventing hip fractures in older people. In: The Cochrane database of systematic reviews . tape 3 , March 31, 2014, doi : 10.1002 / 14651858.CD001255.pub5 , PMID 24687239 .

- ^ Wolfgang Bayer, Wolfgang Gerz: Acid-base balance and osteoporosis. In: empirical medicine. 55, 2006, pp. 142-145, doi: 10.1055 / s-2006-932299 .

- ^ T. Arnett: Regulation of bone cell function by acid-base balance. In: Proc Nutr Soc. 62, 2003, pp. 511-520. PMID 14506899

- ↑ R. Jajoo et al. a .: Dietary acid-base balance, bone resorption, and calcium excretion. In: J Am Coll Nutr. 25, 2006, pp. 224-230. PMID 16766781

- ^ SA New: Intake of fruit and vegetables: implications for bone health. In: Proc Nutr Soc. 62, 2003, pp. 889-899. PMID 15018489

- ↑ LA Frassetto u. a .: Effect of age on blood acid-base composition in adult humans: role of age-related renal functional decline. In: Am J Physiol. 271, 1996, pp. 1114-1122. PMID 8997384

- ↑ KK Frick u. a .: RANK ligand and TNF-alpha mediate acid-induced bone calcium efflux in vitro. In: Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 289, 2005, pp. 1005-1011. PMID 15972386 .

- ↑ NS Krieger u. a .: Regulation of COX-2 mediates acid-induced bone calcium efflux in vitro. In: J Bone Miner Res. 22, 2007, pp. 907-917. PMID 15972386 .

- ↑ a b S. Jehle u. a .: Partial neutralization of the acidogenic western diet with potassium citrate increases bone mass in postmenopausal women with osteopenia. In: J Am Soc Nephrol . 17, 2006, pp. 3213-3222. PMID 17035614

- ↑ M. Marangella et al. a .: Effects of potassium citrate supplementation on bone metabolism. In: Calcif Tissue Int. 74, 2004, pp. 330-335. PMID 15255069

- ↑ DE Sellmeyer u. a .: Potassium citrate prevents increased urine calcium excretion and bone resorption induced by a high sodium chloride diet. In: J Clin Endocrinol Metab . 87, 2002, pp. 2008–2012. PMID 11994333

- ↑ System without control . In: Der Spiegel . No. 44 , 1999 ( online ).

- ↑ The Abolition of Health . In: Der Spiegel . No. 33 , 2003 ( online ).