Kurdish languages

| Kurdish languages | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Spoken in |

|

|

| speaker | 20 to 40 million | |

| Linguistic classification |

|

|

| particularities | Arabic alphabet in Iraq and Iran , Kurdish-Latin alphabet in Turkey and Syria , Cyrillic in Armenia | |

| Official status | ||

| Official language in |

|

|

| Recognized minority / regional language in |

|

|

| Language codes | ||

| ISO 639 -1 |

ku |

|

| ISO 639 -2 |

short |

|

| ISO 639-3 |

short |

|

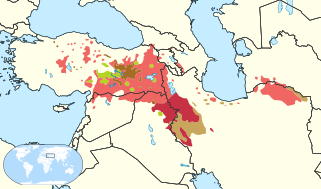

The Kurdish languages (own name کوردی kurdî) belong to the northwest group of the Iranian branch of the Indo-European languages. They are mainly spoken in eastern Turkey , northern Syria , northern Iraq, and northwest and western Iran . As a result of migrations in the past few decades, there are also numerous speakers of Kurdish languages in Western Europe, especially in Germany . There are three Kurdish languages or main dialect groups: Kurmanji (Northern Kurdish), Sorani (Central Kurdish ) and Southern Kurdish .

Kurdish languages

Kurmanji (Northern Kurdish)

Kurmanji (Northern Kurdish, Kurdish Kurmancî or Kirmancî ) is the most widespread Kurdish language. It is spoken by around eight to ten million people in Turkey , Syria , Iraq and Iran, as well as in Armenia , Lebanon and some of the former Soviet republics . Northern Kurdish has been written mainly in the Kurdish-Latin alphabet since the 1930s and is currently going through a process of language development .

Attempts are being made to develop the Botani dialect from Botan in Cizre into the standard language. This dialect was used by Kamuran Bedirxan in the 1920s as the basis for his book on Kurdish grammar. Many Turkish and Arabic loanwords are also being replaced by Kurdish words from other main dialects.

Examples are B. jiyan "life" (originally from the Sorani verb jiyan "to live"), zanist "science" (from South Kurdish zanist-in "to know") and wêje "literature" ( adapted from South Kurdish wişe "word; said"). The real Kurmanji cognates for these words would be jîn / jiyîn , zanîn and bêj- .

Dialects:

- Shengalî (in Mosul ),

- Judikani (in Central Anatolia ),

- Qerejdaxî (in Şanlıurfa , Qamishli etc.),

- Botanî (Boxtî) (in Botan ),

- Serhedkî (in West Azerbaijan , Van , Erzurum , Kars , Ağrı , Mus , etc.),

- Hekkarî (in Hakkâri , West Azerbaijan),

- Behdînî (in Dahuk and West Azerbaijan),

- Torî (in Mardin and Siirt ),

- Xerzî ( Batman and Siirt),

- Qochanî (in Chorasan )

- Birjandî (in Khorasan),

- Elburzî (in Dailam ),

- Western dialect (Marashkî) (in Kahramanmaraş , Gaziantep , Sivas , Tunceli , Adıyaman etc.),

- Central dialect (around Diyarbakır )

- Afrinî (in Afrin , Gaziantep and Şanlıurfa ).

Sorani (Central Kurdish)

Sorani (Central Kurdish) is spoken by around five million people in the south of the Kurdistan Autonomous Region and in western Iran. The Arabic script with Persian special characters is mostly used to write the Central Kurdish , but increasingly the Kurdish-Latin alphabet is also used . There is an extensive literary production.

The expansion of the Sorani is closely linked to the rule of the Baban dynasty of Sulaimaniyya . The economic power of the city spread the central Kurdish in the region and displaced the older Kelhuri and Gorani . Today, Central Kurdish is also used as a source for word creations in Northern Kurdish.

Dialects and dialects:

- Hewlêrî (in Arbil ),

- Pishdarî (south of Erbil)

- Xaneqînî (in Chanaqin ),

- Mukrî (in Mukriyan ),

- Rewandzî (in Rawanduz ),

- Silêmanî / Soranî / Babanî (in Sulaimaniyya),

- Erdelanî (in Ardalan ),

- Sineyî (in Sanandaj ),

- Warmawa (northeast of Erbil),

- Germiyanî (in Kirkuk ),

- Jaffi (spoken by Jaff tribe),

- Judeo Kurdish (in Kermanshah and Hamadan )

South Kurdish

The Südkurdische has many peculiarities and is phonetically older in many ways than the other Kurdish languages. Possibly one can recognize traces of an older Kurdish language class in South Kurdish. Südkurdisch is in western Iran ( Ilam and Kermanshah ) and to the east of northern Iraq ( South Khanaqin , Kirind and Qorwaq) in the lurischen areas Aleschtar, Kuhdescht, Nurabad-e Dolfan and Khorramabad spoken by about four million people. Southern Kurdish was significantly influenced by contact with Persian. The speakers of South Kurdish are predominantly Shiites; many belong to the Ahl-e Haqq religious community .

Dialects:

- Kelhurî , Kolyai, Kirmanshahi, Garrusi, Sanjabi, Malekshahi, Bayray, Kordali

- Leki , Biranavendî, Kurdshûlî (in Fars), Shêx Bizinî (in Turkey, especially around Ankara ), Feylî (in Ilam), Silaxûrî and Xacevendî (in Māzandarān )

classification

Although the three Kurdish languages are somewhat different, there are a number of common features that set them apart from other Iranian languages. According to DN Mackenzie, there is the transition from the postvocal and intervocal Old Iranian * -m- to -v - / - w-, the loss of the first consonant in the consonant groups * -gm-, * -xm- and the reproduction of the Old Iranian * x - Initially with k'- or k-. However, / x / remains in Southern Kurdish (e.g. Kurmanji and Sorani ker. But Southern Kurdish (Kelhuri and Leki) xer "donkey"; Kurmanji kanî. But Southern Kurdish xanî. "Fountain").

Within the Indo-European languages, the Kurdish languages occupy the following position:

-

Indo-European languages

-

Indo-Iranian languages

-

Iranian languages

- Western Iranian languages

- Northwest Iranian languages

- Kurdish languages

- Northwest Iranian languages

- Western Iranian languages

-

Iranian languages

-

Indo-Iranian languages

For a comprehensive classification see the article Iranian languages .

history

Around 1000 BC Iranian tribes immigrated to the area now called Iran and Kurdistan , including the Medes , speakers of a north-west Iranian language. Over the course of the next few centuries, the immigrating Iranian peoples mixed with the non-Aryan resident peoples; this also marked the beginning of the emergence of the Kurds as a people . It is not clear which languages were the origins of the predecessor language of today's Kurdish. Among other things, the Median languages and the Parthian language or a Hurrian origin were discussed . The particularly close relationship between Kurdish and the Central Iranian languages suggests its origin in the Fars region or even central Iran, according to another hypothesis in the Kermanshah region . From there, Kurdish spread to northern Mesopotamia and eastern Anatolia in the following centuries. Loan words from Armenian indicate that the first linguistic contact took place in the 11th century AD.

Little is known about the Kurdish language of the pre-Islamic period. Classical Kurdish poets and authors developed a literary language from the 15th to 17th centuries. The most famous Kurdish poets from this period are Mulla Ehmed (1417–1494), Elî Herîrî (1425–1490), Ehmedê Xanî (1651–1707), Melayê Cezîrî (1570–1640) and Feqiyê Teyran (1590–1660). Due to several factors, however, no Kurdish standard language developed.

Language bans and legal situation

Since the beginning of the 20th century, the states with Kurdish population groups have imposed restrictions on the Kurds and their language in order to assimilate their speakers to the respective national language. As a result, some of the Kurds lost their mother tongue. Some of this repression has now been lifted, so that Kurdish is now the second official language in Iraq. A few years ago in Turkey it was still forbidden to publish in Kurdish or to hold Kurdish-language courses. Kurdish as a private course in schools is legally permitted. In some cases, however, there is still harassment up to and including legal prosecution.

Politicians of Kurdish origin such as Aysel Tuğluk and Ahmet Türk have been forbidden from speaking Kurdish in election campaigns and in parliament since 1983 under Turkish Law No. 2820 on political parties . Failure to comply with the Kurdish ban was tolerated for the first time in the election campaign before the parliamentary elections in June 2011 , or it was neither prevented nor persecuted.

font

The Kurds used the alphabet prevailing in their homeland. In the Middle Ages, for example, they used the Arabic alphabet in the Ottoman and Persian variations. This changed in modern times and especially after the First World War. In Turkey, a Kurdish-Latin alphabet was developed parallel to the new Turkish -Latin alphabet , but its use was not permitted until 2013. In Iran and Iraq, Arabic script is used, while Syria uses Arabic and Latin scripts. In the former USSR , the Kurds used the Cyrillic alphabet .

The three main writing systems are listed below:

| Northern Kurdish | Kyril- lisch |

Central Kurdish |

Trans- lite ration |

Removing language |

example |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A a | А а | ئا ـا ا | a | a | Long as b a hn |

| B b | Б б | ب ـبـ ـب بـ | b | b | German b |

| C c | Щ щ | ج ـج ـجـ جـ | c | dʒ | How Dsch ungel |

| Ç ç | Ч ч | چ ـچ ـچـ چـ | ç | tʃʰ | Sharp as eng lish |

| does not exist, corresponds to ch | Ч 'ч' | does not exist | ç̱ | tʃˁ | Unaspirated ch with narrowed throat |

| D d | Д д | د ــد | d | d | German d |

| E e | Ә ә | ە ـە ئە | e | ε | Short e as in e bridge |

| Ê ê | Е е | ێ ـێ ـێـ ێـ ئێـ | ê | e | Long as E sel |

| F f | Ф ф | ف ـف ـفـ فـ | f | f | German f |

| G g | Г г | گ ـگ ـگـ گــ | G | ɡ | German g |

| H h | Һ һ | هـ ـهـ | H | H | German h |

| Ḧ ḧ | Һ 'һ' | ح حـ ـحـ ـح | H | H | See IPA symbol , missing in German |

| I i | Ь ь | does not exist | i | ɪ | Short as in b i tte |

| Î î | И и | ى ئى ـيـ يـ | î | i | Z long as he l |

| J j | Ж ж | ژ ـژ | j | ʒ | How J ournal |

| K k | К к | ک ـک ـکـ کــ | k | kʰ | aspirated K |

| does not exist, corresponds to ck | К 'к' | does not exist | ḵ | kˁ | Like french C afe unaspirated with narrowed throat |

| L l | Л л | ل ـل ـلـ لــ | l | l | German l |

| does not exist, corresponds to double l | Л 'л' | ڵ ـڵ ـڵـ ڵــ | ḻ | ɫˁ | See IPA mark |

| M m | М м | م ـم ـمـ مــ | m | m | German m |

| N n | Н н | ن ـن ـنـ نــ | n | n | German n |

| O o | О о | ۆ ـۆ ئۆ | O | O | Long as O fen |

| P p | П п | پ ـپ ـپـ پــ | p | pʰ | Aspirated P |

| does not exist, corresponds to double p | П 'п' | does not exist | p̱ | pˁ | Like french P an unaspirated with a narrowed throat |

| Q q | Ԛ ԛ | ق ـق ـقـ قــ | q | q | Guttural |

| R r | Р р | ر ـر | r | ɾ | Rolled r |

| does not exist, corresponds to double r | Р 'р' | ڕ ـڕ | ṟ | rˁ | Rolled r with a narrowed throat |

| S s | С с | س ـس ـسـ ســ | s | s | As wi s sen |

| Ş ş | Ш ш | ش ـش ـشـ شــ | ş | ʃ | How Sch ule |

| T t | Т т | ت ـت ـتـ تــ | t | tʰ | Aspirated T |

| does not exist, corresponds to double t | Т 'т' | ط ـط ـطـ طــ | ṯ | tˁ | Like french T u unaspirated with narrowed throat |

| U u | Ö ö | و ـو ئو | u | ʊ or ʉ | Short u |

| Û û | У у | وو ـوو | û | u | Long as s u chen |

| V v | В в | ڤ ـڤ ـڤـ ڤـ | v | v | How w ollen |

| W w | Ԝ ԝ | و ـو | w | w | How Engl. W ell or w arm |

| X x | Х х | خ ـخ ـخـ خـ | x | χ | Like Ba ch |

| Ẍ ẍ | Ѓ ѓ / Г 'г' | غ ـغ ـغـ غـ | x̱ | ɣ | g as fricative |

| Y y | Й й | ى ئى ـيـ يـ | y | j | How J a or Y is |

| Z z | З з | ز ـز | z | z | How ro s e |

| does not exist, corresponds to ä | Ə 'ə' | ع عـ ـعـ ـع | ʿ / e̱ | ʕ | Voiced throat pressing sound, missing in German |

(*) The transliteration only specifies the transliteration of a template in Arabic script, not a Cyrillic or Armenian.

pronunciation

Following the Kurdish Academy for Language, Kurdish phonetics is described as follows.

Of the 31 letters, the pronunciation of which largely matches the spelling, eight are vowels (ae ê i î ou û) and 23 are consonants (bc ç dfghjklmnpqrs ş tvwxyz). Lower case letters: abc ç de ê fghi î jklmnopqrs ş tu û vwxyz Upper

case letters: ABC Ç DE Ê FGHI Î JKLMNOPQRS Ş TU Û VWXYZ

There is also the digraph Xw.

In Kurdish, only the words at the beginning of the sentence and proper names are capitalized.

Consonants:

| Bilabial | Labiodental | Alveolar | Postalveolar | Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stops | pb | td | kg | q | ||||

| Fricatives | fv | sz | ʃ ʒ | ç | H | |||

| Affricates | ʧ ʤ | |||||||

| Nasals | m | n | ŋ | |||||

| Lateral | l ɫ | |||||||

| Flaps | ɾ | |||||||

| Vibrant | r | |||||||

| Approximante | ʋ | j |

Vowels:

| front | central | back | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| short | long | short | long | short | long | ||

| closed | ı | iː | ʉ | u | uː | ||

| medium | e | eː | ə | O | |||

| open | aː | ||||||

The vowel pairs / ı / and / i / , / e / and / e / and / u / and / u / differ from their respective long and short pronunciation of each other. Short vowels are u , i, and e, and long vowels are written with a circumflex (^), such as û , î, and ê .

Usually Kurdish words are stressed on the last syllable. The endings that appear after activity words (verbs) and nouns (nouns) are an exception. Verbs are stressed on the syllable before the ending (except with the prefixes bı-, ne- / na- / m. And me-, which attract the stress). Nouns are also stressed on the last syllable before the ending (except for the plural ending of the 2nd case, -a (n), which attracts the stress)

Special attention should be paid to the pronunciation:

- The vowels e / ê, i / î and u / û are pronounced differently. The first vowel is short and often weakened and can be spoken indistinctly, while the second is long and clear.

- Attention must be paid to the difference between the hard or voiceless “s” and the soft or voiced “z”, since in German “s” can sometimes be pronounced softly, sometimes hard, such as B. "Hose" or "Bus", "z" in German but always pronounced like "ts".

- Likewise, the vibrating, soft “v” and the “w” spoken only with rounded lips can be distinguished. This difference is also not in German, but z. B. available in English.

Other special features of the sound system:

- The sounds shown above reproduce the northern Kurdish sound system in a somewhat simplified form. In some regions there are the additional sounds' (= ayn), y and h as well as the “emphatic” sounds and the “not breathed” p, t and k. The sounds ayn, h, s and t are “borrowed” from Arabic and do not occur equally in all areas.

- The Kurmanji has no uniform sound system. The south-east mouth species are opposed to the north-west mouth species of Kurmanji. In these dialects, which are spoken in the provinces of Kahramanmaraş, Malatya and Konya, some other sounds are used. In the following, some of the vowels and consonants affected by this phenomenon are listed: the long open a is pronounced like a long open o , as in English Baseb a ll . The short e is often found as a short a . The speakers pronounce the ç like a German z . The sound c is a voiced alveolar affricate , ie a " ds " with a voiced s . In addition, the question pronouns kî (who) and kengî (when) are perceived as “çî” and “çincî”. The prepositions bi (with), ji (from, from) and li (in, to) are pronounced “ba”, “ja” and “la”.

It should be noted that there is a dialect continuum in Kurmanji . This means that the numerous dialects in these two dialect groups flow into one another. There is no alphabet for the north-west mouth species. Most speakers of this Kurmanji language switch to the Turkish language in their correspondence.

grammar

Nouns and pronouns

Case formation

Like many other Iranian languages, Northern Kurdish only distinguishes two cases, namely the subject case ( casus rectus ) and the object case ( casus obliquus ) and thus has a two-cusus inflection . Like Persian, Central and South Kurdish do not know the distinction between case and gender in nouns and pronouns.

The case rectus corresponds to the German nominative , while the case obliquus takes on functions that are usually expressed in other languages with the genitive , the dative , the accusative and the locative . In Kurdish there is also the vocative alongside the casus rectus and the casus obliquus .

The endings of the primary cases are distributed as follows:

| case | Northern Kurdish | Central Kurdish | South Kurdish | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| so called | sg.f. | pl. | so called | pl. | so called | pl. | |

| Rectus | -O | -O | -O | -O | -on | -O | -fishing rod |

| Obliquus | -î | -ê | -on | -O | -on | -O | -fishing rod |

The regular declination in Kurdish:

- bira "brother", jin "woman" and karker "worker"

| case | Prepos. | Northern Kurdish | Prepos. | Central Kurdish | Prepos. | South Kurdish | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| so called m. | so called f. | pl. | so called m. | so called f. | pl. | so called m. | so called f. | pl. | ||||

| Rectus | . | bira-Ø | jin-Ø | karker-Ø | . | bira-Ø | jin-Ø | karker-on | . | bira-Ø | jin-Ø | karker gel |

| Obliquus | . | bira-y-î | jin-ê | karker-on | . | bira-Ø | jin-Ø | karker-on | . | bira-Ø | jin-Ø | karker gel |

Definiteness

In Central Kurdish and South Kurdish there is a kind of article system, in North Kurdish definite nouns like in Persian have no special designation. The Article in Kurdish is suffixed (appended). If the word ends in a vowel, a hiatustilger is inserted (mostly -y-, with rounded vowels also -w-). In the Kurdish-Arabic script, however, the hiatal pilgrim is not always written, cf. xanû-w-eke = "the house":خانوووهکه or. خانووهکه.

- roj "day"

| Northern Kurdish | Central Kurdish | South Kurdish | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| definitely | indefinite | definitely | indefinite | definitely | indefinite |

| roj-Ø | roj-ek | roj-eke | roj-êk | roj-eke | roj-êk |

| roj-Ø | roj-in | roj-ekan | roj-an | roj-ekan | roj-an / -gel |

The central Kurdish “rojeke” can be translated as “the day” and “rojêk” as “a day”.

The suffixed article comes after word formation suffixes and before enclitics such as the enclitic personal pronouns, e.g. B. ker-eke-m = "my donkey" or xanû-w-eke-t = "your house". It is not set if there is a clear reference, i.e. for words like mother , father , name , etc., e.g. B. naw-it çî-ye? = "What 's your name ?" (Literally: Name-your what-is ).

Personal pronouns

In Central and South Kurdish, many pronouns have become obsolete over time, whereas in North Kurdish a large variety of pronouns has been preserved in comparison. For example, the pronoun “ez” for “I” has an old north-west Iranian root. In Young Avestan it was represented as "azǝm", in Parthian as "az" which are palatalized from the Urindo-European root * eǵh 2 óm . In Central and South Kurdish, the obliquus case “min” is used instead, which actually originally meant “my, me” (Urindo-European * me- ), but in its current form “I”. The New Persian went through the same process.

Another difference between Kurmanji and the other Kurdish languages is that Kurmanji has the old pronoun “hun”, which comes from the Avestian “yušma-” and was “aşmā” in Parthian and Middle Persian. The counterpart to this is the “şumā / şomā” in Persian and “şıma” in Zazaki. In Kurmanji one can start from an older basic form with "ş", from which the typical / ş /> / h / conversion as in "çehv" (eye, Persian: çaşm ) and "guh" (ear, Persian: gūş ) "Hun" should have originated. It is noteworthy that the Kurmanji was able to preserve the ancient Indo-European forms * tú ( du. Modern English : thou , Old English : þū ) and * te ( dich. Modern English : thee , old English: þē ) in their original forms to this day.

| Pers / Num | Kurdish | Persian | Zazaki | Talisch | meaning | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North | Central | south | ||||||||

| Casus rectus | ||||||||||

| 1st sg. | ez | min | min | man | ez | āz | I | |||

| 2.sg. | do | to | do | to | tı | tə | you | |||

| 3.sg.m. | ew | ew | ew | ū, ān | O | av | he / it | |||

| 3.sg.f. | ew | ew | ew | ū, ān | a | ? | she | |||

| 1.pl. | em | ême | îme | mā | ma | ama | we | |||

| 2.pl. | hun | êwe | îwe | şomā | şıma | şəma | her | |||

| 3.pl. | ew | ewan | ewan | işān, ānhā | ê | avon | she pl. | |||

| Casus obliquus / ergative | ||||||||||

| 1st sg. | min | min | min | man | mı (n) | mə | my, me, me | |||

| 2.sg. | te | to | do | to | to | tə | your (s), you, you | |||

| 3.sg.m. | wî | ew | ew | ū, ān | ey | ay | his, him, him | |||

| 3.sg.f. | wê | - | - | - | ae | - | you (s), you, you | |||

| 1.pl. | me | ême | îme | mā | ma | ama | our, us, us | |||

| 2.pl. | we | êwe | îwe | şomā | şıma | şəma | yours, you, you | |||

| 3.pl. | wan | ewan | ewan | işān, ānhā | inan | avon | her (s), them, she pl. | |||

It should be noted that the Persian / Talic ā and a in Kurdish / Zazaki are rendered as a and e (Example: Persian barf برف"Snow", Kurmanji berf ), one would also write Talisch av in the Kurdish alphabet as ev .

Demonstrative pronouns

The two demonstrative pronouns in the Kurdish dialects have a distinction between near and far, which are comparable to those of the English "this" and "that". The 3rd pers. Sing. Of the personal pronoun is used for the demonstrative pronoun. The one in front of the slash indicates close and the one following the slash indicates far.

Demonstrative pronouns

| shape | Kurdish | Persian | Zazaki | meaning | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North | Central | south | ||||

| Rectus | ||||||

| masculine, feminine, plural | ev / ew | eme / ewe emane / ewane (plural) |

eye / ewe eyane / ewane (plural) |

in / un | no, na, nê | this, this, this pl. |

| Obliquus | ||||||

| masculine | vî / wî | eme / ewe | eye / ewe | in / un | ney | this, this |

| feminine | vê / wê | eme / ewe | eye / ewe | in / un | nae | this, this |

| Plural | van / wan | emane / ewane | eyane / ewane | inan / unan | ninan | this, this |

Question pronouns

| German | Northern Kurdish | Central Kurdish | South Kurdish |

|---|---|---|---|

| who | kî | kê | kî |

| What | çi | çî | çe |

| How | çawan / çawa / çer | çon | çûn / çün |

| Why | çima / çire | bo (çî) | erra (çe) |

| Where | ku / kudê | kwê | kûre / kû |

| When | kengî | key | key |

| Which | kîjan | came | came |

| How much | çend | çend | çend |

Pronominal suffixes

In Central Kurdish and South Kurdish there are also pronominal suffixes like in Persian. They are tied to the end of a word and fulfill the function of personal pronouns. These enclitic personal pronouns were also included in Old Iranian and may be based on an influence of isolated pre-races. Example:

| German | Central and South Kurdish | Persian |

|---|---|---|

| Surname | naw | nâm |

| My name | nawim | nâmäm |

The proninal suffixes:

| German | Central and South Kurdish | After vowel | Persian |

|---|---|---|---|

| my | -in the | -m | -am |

| your | -it | -t | -at |

| be | -î & -ê | -y | -äş |

| our | -man | -man | -emân |

| your | -tan | -tan | -etân |

| their | -yan | -yan | -it on |

Examples in the singular:

- "Kurr" means "son" or "boy" in Kurdish

| German | Central and South Kurdish | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| my son | Kurrim | |||

| Your son | Kurrit | |||

| His / her son | Kurrî & Kurrê | |||

| Our son | Kurrman | |||

| Your son | Kurrtan | |||

| Your son pl. | Kurryan | |||

The vowel -i- of the first and second person falls after the vowel and can be placed after the consonant in the plural forms. The enclitic personal pronouns can stand for all parts of the sentence with the exception of the subject (note the peculiarity of transitive verbs in the past, see below), i.e. for possessive pronouns , for the indirect object , for complements of a preposition and in the present tense also for the direct object .

In the past of transitive verbs, they function as agent markers and cannot stand for the direct object. So you congruent with the subject.

Another special feature is their position. They are generally in the second position of their phrase. If they function as possessive pronouns, they are attached directly to the reference word. If they represent a complement governed by a preposition, they can be added directly to the preposition (e.g. lege l -im-da = "with me") or they appear on the word in front of the preposition (e.g. : agireke dûke l -î lê- he l destêt. = "Smoke rises from the fire"; literally: the fire, smoke-from-him rises , whereby the enclitic personal pronoun -im is governed by the preposition lê ).

If the only possible carrier in the sentence is the verb itself, the enclitic personal pronouns are either attached to verbal prefixes (eg: na- t -bînim = “I do n't see you .”) Or to the verb ending .

Izafe

When a word is defined more precisely, the word in Kurdish, as in other Iranian languages, is connected to the defining word via an Izafe (in Arabic: addition). Example:

| German | Kurmanji | Sorani | South Kurdish |

|---|---|---|---|

| House | Times | Times | Times |

| My house | Mala min | Malî min | Mali min |

The Izafe has a singular form for male and female and a common form for both genders in the plural. There is also a casus rectus and a casus obliquus of the Izafe. In Sorani and South Kurdish there is no gender distinction in the Izafe construction.

Izafe forms in Kurdish:

| Kurmanji | Sorani | South Kurdish | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| case | so called | sg.f. | pl. | so called | sg.f. | pl. | so called | sg.f. | pl. |

| Rectus and obliquus | -ê | -a | -ên / -êt | -î | -î | -anî | -i | -i | -ani / geli |

The following examples in Kurmanji ( ker "donkey", cîran "neighbor"; the connection suffix is printed in bold):

| case | Form with Izafe | meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Rectus | ker- ê cîran-î | the neighbor's donkey |

| . | ker- a ciran-î | the neighbor's donkey |

| . | ker- a cîran-ê | the neighbor's donkey |

| . | ker- ên cîran-î | the neighbor's donkey |

| . | ker- ên cîran-an | the neighbors' donkeys |

| Obliquus | ker- ê cîran-î | the neighbor's donkey |

| . | ker- a cîran-î | the neighbor's donkey |

| . | ker- a cîran-ê | the neighbor's donkey |

| . | ker- ên cîran-î | the neighbor's donkey |

| . | ker- ên cîran-an | the neighbors' donkeys |

verb

Ergative

Kurmanji and Sorani are two of the few Indo-European languages that use the ergative . In Kurmanji, for example, the agent in transitive verbs is not in the case rectus, but in the case obliquus (cf. also Zazaki ). The Patiens , however, that the German by an accusative - object is displayed, is at the casus rectus. In Sorani, which no longer knows any case distinctions, the pronominal suffixes, which are never an agent, refer to transitive verbs and mark the patient. If possible, place them next to the word in front of the verb. South Kurdish has no ergative; here the agent is in the case rectus and the patient in the case obliquus. Casus rectus and casus obliquus in the personal pronouns "I" and "du" used in the following example sentences are the same in both languages.

Examples:

| German | Kurmanji | Sorani | South Kurdish |

|---|---|---|---|

| I saw you | Min casus obliquus tu casus rectus dîtî | Min casus obliquus to casus rectus m pronominal suffix (tom) dîtît | Min casus rectus tu casus obliquus dîm |

(The past stem of the verb is "dî-" in South Kurdish and not "dît-" as in the other two.)

But:

| German | Kurmanji | Sorani | South Kurdish |

|---|---|---|---|

| I came | Ez Casus rectus hatim | Min casus rectus hatim | Min casus rectus hatim |

Here the agent is in Kurmanji and Sorani in the case rectus, because "to come" is an intransitive verb. Intransitive verbs have no patient. In South Kurdish, which is not an ergative language, the agent is in both examples in the case rectus.

Present

Indicative and Continuative

The indicative present is formed in Kurdish by placing a prefix (de-, me-) plus the personal ending (-im). In South Kurdish, the prefix “di-” has been dropped from most of the verbs.

Example: "to go", whose trunk is -ç- in Kurdish , in the indicative present tense:

| Num / pers | Kurmanji | Sorani | South Kurdish | Leki | meaning |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st sg. | ez di ç im | min e ç im | min ç im | min me ç im | I go |

| 2.sg. | do diçî | to eçît | tu çîd | do meçîd | you go |

| 3.sg. | ew diçe | ew eçêt | ew çûd | aw meçûd | he goes |

| 1.pl. | em diçin | ême eçîn | îme çîm | îme meçîm | we go |

| 2.pl. | hûn diçin | êwe eçin | îwe çîn | îwe meçîn | you go |

| 3.pl. | ew diçin | ewan eçin | ewan çin | ewan meçin | they go |

The continuative is formed by adding a suffix -e (after a vowel: -ye) to the indicative form. In colloquial language, the continuative is rarely found in the present tense; it is mainly used in academic language. In German it is translated as “I'm going straight”.

| Num / pers | Kurmanji | Sorani | South Kurdish | English | meaning |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st sg. | ez diçime | I am going | I am walking | ||

| 2.sg. | tu diçîye | you are going | you are leaving | ||

| 3.sg. | ew diçeye | he is going | he is leaving | ||

| 1.pl. | em diçine | we are going | we're leaving | ||

| 2.pl. | hûn diçine | you are going | you are walking | ||

| 3.pl. | ew diçine | they are going | they are just leaving |

Subjunctive and imperative

In Kurdish, as in all other Iranian languages, the subjunctive and imperative present tense are formed with the prefix bi- . First comes the prefix bi- , then the verb stem and finally the personal ending.

Example for the present subjunctive:

| Num / pers | Kurmanji | Sorani | South Kurdish | meaning |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st sg. | ez bi ç im | min bi ç im | min bi ç im | (that) I'm going |

| 2nd sg | do biçî | to biçît | do biçîd | you go |

| 3.sg. | ew biçe | ew biçêt | ew biçûd | he / she / it goes |

| 1.pl. | em biçin | ême biçîn | îme biçîm | (that) we're going |

| 2.pl. | hûn biçin | êwe biçin | îwe biçîn | you go |

| 3.pl. | ew biçin | ewan biçin | ewan biçin | (that) they go |

Example for the imperative present tense:

| Num / pers | Kurmanji | Sorani | South Kurdish | meaning |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.sg. | (do) biçe! | (to) biçe! | (tu) biçû! | go |

| 3.sg. | ew biçe | ew biçêt | ew biçûd | he / she / it should go! |

| 1.pl. | em biçin! | ême biçîn! | îme biçîm! | let's go! |

| 2.pl. | (hûn) biçin! | (êwe) biçin! | (îwe) biçin! | go! |

| 3.pl. | ew biçin | ewan biçin | ewan biçin | let them go! |

Future tense

Instead of di- the prefix bi- is used for the future tense . In addition, it is characterized by a particle that is attached to the personal pronoun without stress. It is often -ê , in written Kurdish dê and wê are preferred, which are written separately.

Example:

- ezê biçim "I'll go" - (written Kurdish )

- ew dê biçe "she will go"

Kurdish vocabulary

Kurdish is one of the few Iranian languages that, in spite of Islamization, were largely able to retain their original vocabulary, even if there are many Arabic loanwords. As an important official and cultural language, Persian was more strongly influenced by Arabic than Kurdish, a language that enjoys natural protection in the mountainous regions.

The Indo-European origin of Kurdish can still be seen in many words today. Examples of words that have not been subjected to major sound shifts.

| Proto-Indo-European | Kurdish | German |

|---|---|---|

| * b h réh 2 door | bira, bra | Brothers |

| * b h ER- | birin / birdin | (bring) |

| * h 3 b h rest | birû | (Eyes) brew |

| * h 1 nḗh 3 mṇ | nav, naw | Surname |

| * néwos | nû, nev, new | New |

| * s w éḱs | şeş | six |

| * h 2 str | histêrk, stêr, hestare | star |

Examples of words that have clearly moved away from the original Indo-European form due to sound shifts:

| Proto-Indo-European | Old Iranian | Kurdish | German | Today's meaning in Kurdish |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| * l eu k - | r eu ç - | roj | shine, light | Day |

| * s eptṃ | h epte- | notebook | seven | seven |

| * s wé s or | h ve h he | xweh, xweşk, xwuş, xwuşk, xweyşik | sister | sister |

| * ǵ eme- | z āmāter | zava, zawa | (Groom) | groom |

| * ǵ neh 3 - | z ān- | zanîn | can | knowledge |

See also

literature

- David Neil MacKenzie: Kurdish dialect studies . Oxford University Press, London 1962 (North and Central Kurdish dialects; 1961/1962).

- Paul Ludwig: Kurdish word for word . Peter Rump, Bielefeld 2002, ISBN 3-89416-285-6 (Kurmandschi).

- Emir Djelalet Bedir Khan , Roger Lescot: Kurdish grammar . Verlag Kultur und Wissenschaft, Bonn 1986, ISBN 3-926105-50-X (Kurmandschi).

- Feryad Fazil Omar: Kurdish-German Dictionary . Institute for Kurdish Studies, Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-932574-10-9 (first edition: 1992, Kurmandschi , Sorani).

- Abdulkadir Ulmaskan: Ferheng / Dictionary Kurdî-Almanî / Kurdish-German & Almanî-Kurdî / German-Kurdish . Kurdish Institute for Science and Research, o. O. 2010, ISBN 3-930943-60-3 .

- Khanna Omarkhali: Kurdish Reader, Modern Literature and Oral Texts in Kurmanji. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2011, ISBN 978-3-447-06527-6 .

- Petra Wurzel: Kurdish in 15 lessons . Komkar, Cologne 1992, ISBN 3-927213-05-5 .

- Kemal Sido-Kurdaxi: Kurdish phrasebook . Blaue Hörner Verlag, Marburg 1994, ISBN 3-926385-22-7 ( Kurmandschi ).

- Joyce Blau: Manuel de Kurde. Dialects Sorani. Grammaire, textes de lecture, vocabulaire kurde-français et français-kurde . Librairie de Kliensieck, Paris 1980, ISBN 2-252-02185-3 .

- Jamal Jalal Abdullah, Ernest N. McCarus: Kurdish Basic Course. Dialect of Sulaimania, Iraq . University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor 1967, ISBN 0-916798-60-7 .

- Petra Wurzel: Rojbas - Introduction to the Kurdish language . Reichert, Wiesbaden 1997, ISBN 3-88226-994-4 .

- Hüseyin Aguicenoglu: Kurdish reading book. Kurmancî texts from the 20th century with glossary . Reichert, Wiesbaden 2005, ISBN 3-89500-464-2 .

- Kamiran Bêkes (Haj Abdo): Bingehên rêzimana kurdî, zaravê kurmanciya bakur . Babol Druck, Osnabrück 2004.

Kurdish-English dictionaries

- Michael Lewisohn Chyet: Kurdish-English dictionary - Kurmanji-English . Yale University Press, New Haven 2003, ISBN 0-300-09152-4 .

- Nicholas Awde: Kurdish-English / English-Kurdish (Kurmanci, Sorani and Zazaki) Dictionary and Phrasebook . Hippocrene Books, New York 2004, ISBN 0-7818-1071-X .

- Raman: English-Kurdish (Sorani) Dictionary . Pen Press Publishers, 2003, ISBN 1-904018-83-1 .

- Salah Saadallah: Saladin's English-Kurdish Dictionary. 2nd Edition. Edited by Paris Kurdish Institute. Avesta, Istanbul 2000, ISBN 975-7112-85-2 .

- Aziz Amindarov: Kurdish-English / English-Kurdish Dictionary . Hippocrene Books, New York 1994, ISBN 0-7818-0246-6 .

Web links

- Kurdish languages . In: Ehsan Yarshater (Ed.): Encyclopædia Iranica (English, including references)

Institutes

Dictionaries

- AzadiyaKurdistan Dictionary German-Kurdish (Kurmancî)

- German-Kurdish

- German-Kurdish Dictionary Pauker (Kurmancî)

- German Kurdish Dictionary Hablaa

- German-Kurdish Dictionary Ferheng (Kurmancî)

- English-Kurdish Dictionary (Soranî)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Only very rough estimates are possible. SIL Ethnologue gives estimates, broken down by dialect group, totaling 31 million, but with the caveat of "Very provisional figures for Northern Kurdish speaker population". Ethnologue estimates for dialect groups: Northern: 20.2M (undated; 15M in Turkey for 2009), Central: 6.75M (2009), Southern: 3M (2000), Laki: 1M (2000). The Swedish Nationalencyklopedin listed Kurdish in its "Världens 100 största språk 2007" (The World's 100 Largest Languages in 2007), citing an estimate of 20.6 million native speakers.

- ↑ https://www. britica.com/topic/Kurdish-language

- ↑ European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages , Regional and Minority Languages in Europe

- ↑ https://www.ethnologue.com/language/kmr

- ↑ South Kurdish language

- ↑ a b Garnik Asatrian: The Ethnogenesis the Kurds and early kurdisch-Armenian contacts. In: Iran & the Caucasus. 5, 2001, pp. 41-74.

- ^ A. Arnaiz-Villena, J. Martiez-Lasoa, J. Alonso-Garcia: The correlation Between Languages and Genes: The Usko-Mediterranean Peoples. In: Human Immunology. 62, No. 9, 2001, p. 1057.

- ^ Gernot Windfuhr: Isoglosses: A Sketch on Persians and Parthians, Kurds and Medes. Monumentum HS Nyberg II (Acta Iranica-5), Leiden 1975, pp. 457-471.

- ↑ A. Arnaiz-Villena, E. Gomez-Casado, J. Martinez-Laso: Population genetic relationships between Mediterranean populations determined by HLA distribution and a historic perspective . In: Tissue Antigens . 60, 2002, p. 117. doi : 10.1034 / j.1399-0039.2002.600201.x

- ↑ Because he distributed tourism brochures in Kurdish, a mayor in Diyarbakr is supposed to go to prison. A trip to southeastern Turkey, where the judiciary not only hunts people, but also the letters . In: The time . No. 49/2007.

- ↑ For a few bits of Kurdish . In: Der Spiegel . No. 10 , 2009, p. 92 ( online ).

- ↑ Law No. 2820 of April 22, 1983 on political parties, RG No. 18027 of April 24, 1983; German translation by Ernst E. Hirsch In: Yearbook of Public Law of the Present (New Series). Volume 13, Mohr Siebeck Verlag, Tübingen 1983, p. 595 ff.

- ^ Caleb Lauer: The competing worlds of written Turkish. In: The National. December 12, 2013, accessed March 20, 2015 .

- ↑ Christian Bartholomae: Old Iranian Dictionary . KJ Trübner, Strasbourg 1904, p. 225.

- ^ David Neil MacKenzie: A concise Pahlavi dictionary . Oxford University Press, London / New York / Toronto 1971, p. 15.

- ↑ Manfred Mayrhofer: Etymological Dictionary of the Old Indo-Aryan (EWAia) . Heidelberg 1986-2001, p. 155.

- ↑ Manfred Mayrhofer: Etymological Dictionary of the Old Indo-Aryan (EWAia) . Heidelberg 1986-2001, p. 284.

- ↑ Christian Bartholomae: Old Iranian Dictionary . KJ Trübner, Strasbourg 1904, p. 1302.

- ^ Mary Boyce : A Word List of Manichaean Middle Persian and Parthian. In: Textes Et Memoires. Tome II, Suppl. Leiden 1974, p. 16.

- ↑ Manfred Mayrhofer: Etymological Dictionary of the Old Indo-Aryan (EWAia). Heidelberg 1986-2001, p. 682.

- ^ JP Mallory, DQ Adams: The Oxford introduction to Proto-Indo-European and the Proto-Indo-European world. 2006, pp. 416-417.

- ↑ Wolfgang Schulze: Northern Talysh . Lincom Europa, 2000, p. 35.