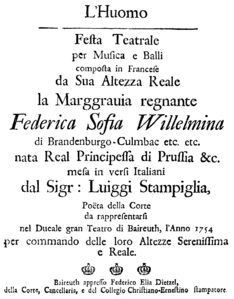

L'Huomo

| Work data | |

|---|---|

| Title: | L'Huomo |

| Original title: | L'Homme |

Title page of the libretto from 1754 |

|

| Shape: | Festa teatrale in one act for singers, orchestra, choir and ballet |

| Original language: | French (original), Italian (opera libretto), German (contemporary German adaptation by Philipp Cuno Christian von Bassewitz ) |

| Music: | Andrea Bernasconi Baldassare Galuppi (2 arias) Johann Adolf Hasse (3 arias) Wilhelmine von Bayreuth (2 cavatines) |

| Libretto : | Luigi Stampiglia (Italian) |

| Literary source: | Wilhelmine von Bayreuth (French) |

| Premiere: | June 19, 1754 |

| Place of premiere: | Bayreuth, Margravial Opera House |

| Playing time: | (1 act) |

| people | |

|

at the premiere:

|

|

L'Huomo is a Festa Teatrale in one act with music and dance based on the French operatic poem L'Homme created by Wilhelmine von Bayreuth . The Italian translation for it comes from the Bayreuth court librettist Luigi Stampiglia , which was set to music by the Munich vice- conductor Andrea Bernasconi . For the allegorical act of good and evil forces on earth, by which the protagonists Animia and Anemone , the female and the male soul , are moved, Wilhelmine, as she writes, allowed herself to be drawn from the " philosophical system" ( Zoroastrianism ) of Zoroaster ( Zarathustra , ancient Iranian religious founders ). It premiered on June 19, 1754 in the Margravial Opera House in Bayreuth on the occasion of the visit of her brother Frederick the Great .

Action in one act

- Stage designs by Carlo Galli da Bibiena : oak forest, alternating with a terrible cave.

While Animia and Anemone sleep deeply in a meadow - separated from each other - the good spirit ( Il Buon Genio ) appears from the clouds and sings of the beginning time of virtue and reason. He sees the two sleeping "mortals" ( les Mortels , the female and the male soul) and hurries to proclaim his message to all people. Animias and Anemones names are "equally significant words" and anagrams for the female and male soul. The good spirit frees reason, its daughter Negiorea , and with it virtue and joys, which until then had all been tied up in a "terrible cave". After a story ballet tells Negiorea the dancers to address Animias and Anemones. They do this by equipping the two sleepers with motto, called "motto" of honesty .

One of the dancers is the personified “honest love”, whose attempt to wake Animia and Anemone darkens the stage. IL Cattivo Genio (evil spirit) appears with thunder and flames and drives away the followers of the good spirit. During the dance of his followers, whom he commands to destroy humanity, the evil spirit discovers the two sleeping people, whereupon the dancing people remove the signs of righteousness from Anemone. They fail at Animia, but they rob her of innocence and give her self-love, pride and jealousy. Negiorea , the (invisible) reason prevents Animia from being hit by the arrow of L'Amor Incostane (fleeting love), which hits Anemone alone. Both mortals wake up from their sleep. They are strangers to each other and look at each other with admiration. Their approaches end in a sung love duet ( Scena Sesta ).

- Stage sets: palm forest in which the gods of love stroll; then a mountainous, impassable landscape, alternating with a mountainous landscape, in which an altar is placed around which the choir of the Spiriti Celesti gathers; Finally: landscape and crystal palace with translucent columns, in the distance the Greek port city of Piraeus .

Animia misses the tokens of true loyalty in Anemone (which have been taken from him), becomes puzzled and the intrigue takes its course. Volusia , lust and Incosia , impermanent love, take possession of Anemones, who completely forgets Animia. Animia can resist temptation. At the same time - as the main thing, on a higher level - the battle of Negiorea with the evil forces takes place, in which ultimately good wins, as Anemone sees his injustice and is influenced to repentance. Animia generously forgives him.

Question about the subject

In this simple parable about the lovers Animia and Anemone - the seduction of the male soul, its conversion through the intervention of reason (negiorea) and the generous forgiveness by the female soul - a certain simplicity in the demonstration of the moral lead of the female principle is striking . At a courtly theater performance that was specially designed for a state event, Frederick the Great's visit to the Franconian residence, it is surprising that Wilhelmine explicitly does not perform a "royal homage" by the ruling government of Brandenburg = Culmbach in the form of a corresponding act, but one puts female soul in the foreground of her singing game L'Homme , ( The Man ). This question could be answered in the Scena Sesta , in which both souls wake up from their sleep: Animia, the female soul is recognized by the male as the autre moimême mais bien plus parfait (the other, much better self).

Background and meaning

The one-act Festa teatrale - a moralizing musical theater piece of the Enlightenment on a poetic level - is modestly described by the theater director Wilhelmine in the argument (preface) as a simple allégorie (German preface: a mere parable , a kind of lyrical poem ) with a sujet philosophique sur un Théatre d 'opera called. The subject of Wilhelmine, who was oriented towards French culture, is interesting in view of the French opera of the time, which was the scene of the so-called Buffonist dispute in the 1750s : Here, in 1752, Jean-Jacques Rousseau with his opera Le devin du village for a comprehensive, consequent Europe-wide French success ensured. Like Rousseau, Wilhelmine thematizes the needs of a divided pair of lovers (female and male soul) and their reunification. With Rousseau the Devin (village fortune teller) is the “saving angel” for reconciliation, with Wilhelmine this role is played by Negiorea , the personified reason, according to the Zoroaster system led by the opera director, which is realized in the dialogue between the two souls.

The key point is that the theater director expressly understands both sexes as actors under the title Der Mensch ( L'Huomo ); With this title she takes a position on an old identification problem of women, as programmed in the Romance stem "homo", which only contains the male gender. Animia's moral lead, which is the theme of the opera, is remarkable in view of the quarrel des femmes around this problem. According to Christian teaching, as it has been discussed since the Renaissance , only Adam could choose and determine his life. The humanist Giovanni Pico della Mirandola wrote the famous Oratio de hominis dignitate (on human dignity), printed in 1496 . In contrast, in L'Huomo it is only the feminine soul Animia that obeys reason, negioreá and thus not fleeting love .

“A bright ray of truth suddenly penetrates me. Go wrong! grab yourself, you just want to trick me. "

Both sexes act independently, but the female wins morally. This is a source of conflict for the Querelle des femmes discussed in the salons at the time . Wilhelmine puts it very simply:

"The author [Wilhelmine] introduces [...] a male and a female [soul] in order to encourage the attention of his various listeners [of both sexes] all the better."

Wilhelmine comments on this that a good outcome like this - the moral victory of women [= the female soul] - is only possible in the theater.

“Il est fort á craindre, que ce triomphe n'existera jamais, que sur le theater. »

"It is cheap to fear that this triumph could never be shown otherwise than on the Schaubühne."

To the old Italian word L'Huomo

“L'Huomo” ( old Italian spelling) as the opera title does not indicate any stage action, such as the historical figure Semiramis as the headline to Wilhelmine's libretto of her previous opera. The definition of the word L'Huomo is “man” and “man” at the same time, but not “woman”. This led to serious discussions and rhetorical, often misogynistic quibbles over the centuries, so-called Querelle des femmes . If one visualises the activities of the enlightened theater woman Wilhelmine, who has been active in French theater and Italian operas for the stages of her court since 1737 , the question arises whether the author was particularly interested in the subject of the Querelle in her title, even if she was not specifically concerned with it indicates - or precisely because of it.

The centuries-old, lively writing of the Querelle is illustrated, for example, by the pamphlet Whether women are human beings or not? (1595, German version 1618) illustrated. It says the misogyne Benedictine - Debater :

"The little word homo is derived from humo, from the earth, so the woman cannot be or be called a human being, then she cannot come from the earth, because from the flap ribs."

Wilhelmine spoke and wrote mainly the language of the educated nobility, French, and France was the land of salons where subjects such as those of the querelle were discussed.

French-Italian hybrid

Wilhelmine's one-act Festa teatrale , a singing play with dances mixed into 23 scenes, is a hybrid of Italian opera seria and French Fête en Musique . With the culturally French-oriented Margravine, one might think that she was looking at the one-act opera ( Interméde ) by Jean Jacques Rousseau Le devin du village , which has been staged with great success in Paris since 1752 , because this musical theater was "only" about her Reconciliation of a divided (rural) pair of lovers, who are reconciled again by switching on the village fortune teller and magician. In L'Huomo the relationship drama takes place on a higher level, so the role of the village fortune teller falls to a buon genio (good spirit) in the form of his daughter, reason. Four ballets and seven choirs are elements of the French tragédie lyrique integrated into the plot ; dance music and choreography, early examples of narrative ballets, are now lost. Two cavatins of the good spirit, composed by Wilhelmine, are placed in the center. A total of sixteen da capo arias are provided, mostly at the end of a scene , as in the Italian opera seria. Two ballet masters are given in the libretto. The final ballet bears the programmatic heading Rinaldo and Armide after the ancient mythological material that Georg Friedrich Handel set to music in his opera Rinaldo of the same name . The title page of the libretto of his Hamburg performance with the representation of a round arch architecture is similar to the stylized graphic design of the “palm forest” in Carlo Galli da Bibiena's stage design for L'Huomo.

The teaching of Zoroaster

Zarathustra , ancient Iranian founder of religion, probably from Bactria (2nd or 1st millennium BC) and his teaching preoccupied the Europeans especially in the Age of Enlightenment. In France, Voltaire, with whom Wilhelmine was friends, was the most important writer on the subject. "The Zoroastrian dualism of good and bad was known in Europe since the reports of the ancient Greeks". In her textbook on L'Huomo , Wilhelmine writes only the following in relation to Zoroaster, which shows that she counts him among the philosophers:

«L'Idèe du bon et du mauvais Genie, qu'il introduit sur la scene, est tirée du sistème de Zoroastre, famous philosopher, à ce qu'òn croit, de la Bactriane. »

In Wilhelmine's library, according to the catalog of the University of Erlangen , there is a text book of the opera Zoroastre performed by Jean Philippe Rameau in 1749 and a French book Zoroastre . The opera libretto assigned to Louis de Cahusac (title page anonymous), and what flowed from it into Wilhelmine's libretto L'Homme , was examined by: Thomas Betzwieser Cahusac and the consequences - considerations on the performance character of 'L'Huomo' in Bayreuth 1754 .

reception

The idea of the subject of the opera L'Huomo , in which souls are the main characters, was encountered 110 years earlier in Das Geistliche Waldgedicht or Freudenspiel, called Seelewig by the Nuremberg baroque composer Sigmund Theophil Staden , Nuremberg 1644; Text by Georg Philipp Harsdörffer . A possible reference to this work has not yet been discussed. In contrast to L'Huomo, Seelewig is about the temptation of the female soul alone.

With L'Argenore, L'Huomo is one of the only two operas that have been (completely) preserved from Wilhelmine's 20-year-old Bayreuth opera director 1737–1758.

The Bayreuth court calendar of 1755 (which was designed in the previous year) with the first recorded Etat de l'opera , of which Philipp Christian Cuno von Bassewitz is named, gives an indication of the increased and more expensive equipment of the Bayreuth opera maintenance in the year of the premiere in 1754 also wrote the German adaptation. Since the beginning of the 1750s, after the last work on the Margravial Opera House was finished, the opera director Wilhelmine showed increased activity with self-made libretti. In 1751 she was accepted into the Roman Accademia dell'Arcadia , a literary academy to which the librettist Metastasio also belonged. On the occasion of her brother Friedrich II's visit to Bayreuth, she had the libretto for L'Huomo printed in three languages (Italian / French and Italian / German). Wilhelmine entrusted the setting to Munich Vice Kapellmeister Andrea Bernasconi , who had taken up his position at the court of the Bavarian Elector in 1753.

The Bayreuther Zeitung reported on June 22, 1754 about the first conception of man [...] which testifies to the excellent mental qualities of its author [Wilhelmine] . She praised the great accuracy and splendor of the performance. His Majesty [Frederick the Great] seemed delighted with the poem, the music, the dances, and the machines . The newspaper did not comment on the content. The same text as in the Bayreuther Zeitung, but in French, appeared ten days later, on July 2, 1754, in the Gazette de Cologne .

On June 27, 1754, Count Lehndorff, Chamberlain of the Queen, wife of Frederick the Great Elisabeth Christine, wrote nothing in his diary about the opera, but he did write about the (inevitable) tribute to the king, which was "at one of the festivals" in Bayreuth, obviously independent of the Performance of the opera took place:

“The King returns from his trip to Baireuth very satisfied. At one of the festivals, people adored their image by letting a crown with the inscription: 'For the most worthy' descend from heaven onto their image. "

In 1958 Gilbert Gravina prepared a German version of L'Huomo for the first re-performance in Wilhelmine's 200th year of death. This took place at the same place as the first performance in 1754. The furnishing and extensive processing for it comes from the Bavarian Staatskapellmeister Robert Heger at the time. The title chosen was The Triumph of Light . Fifty years later (2009) the opera in Gotha and Bayreuth was on the program on the occasion of the double anniversaries in 2008/2009 on the 250th anniversary of Wilhelmine's death and 300th birthday.

literature

- Gisela Bock : Querelle des femmes. A European dispute about the sexes. In: Women in European History. From the Middle Ages to the present. C. H. Beck, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-406-46167-0 , pp. 13-52

- Sabine Henze-Döhring : The musical composition of the opera L'Huomo. (PDF; 2.8 MB) Lecture at the symposium on the occasion of the revival of L'Huomo: The Musical Theater of Margravine Wilhelmine, October 2, 2009, Bayreuth Art Museum. (No longer available online.) In: uni-marburg.de. December 1, 2009, archived from the original on November 7, 2016 (lecture text with footnotes).

- L'Homme, L'Huomo, Man. Libretti in French, Italian and German. University libraries Bayreuth, Erlangen (both only Italian / French) and Rostock (only Italian / German; digitized version , Rostock University Library ).

- H. Lommel: The Iranian Religion. In: The religions of the earth. Their essence and their history. Founded by Carl Clemen. 2nd Edition. Munich 1949 (1st edition 1927), OCLC 1069912929 , pp. 133-150.

- Peter Niedermüller, Reinhard Wiesend (Hrsg.): Music and theater at the court of the Bayreuth Margravine Wilhelmine. Symposium on the 250th anniversary of the Margravial Opera House on July 2nd, 1998 (= Musicological Institute of Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz [Ed.]: Writings on musicology. Volume 7). Are Edition, Mainz 2002, ISBN 3-924522-08-1 .

- Gustav Berthold Volz (Ed.): Friedrich the Great and Wilhelmine of Bayreuth. Correspondence. Volume II. Publishing house by KF Koeler, Leipzig 1926.

- Reinhard Wiesend: Margravine Wilhelmine and the opera. In: Paradise of the Rococo. Galli Bibiena and the court of muses of Wilhelmine von Bayreuth. Exhibition catalog. Edited by Peter O. Krückmann. Prestel, Munich 1998, ISBN 3-7913-1964-7 .

Web links

- Stephani Elliott: Lust wears green / Bernasconi's “L'Huomo” in Bayreuth. In: stephanielliott.com (theater review of the performance in Bayreuth 2009)

- Franz R. Stuke: Baroque fascination. (No longer available online.) In: opernnetz.de. August 14, 2009, archived from the original on October 7, 2015 (review of the performance in the Ekhof-Theater , Gotha 2009).

- Andrea Bernasconi / Wilhelmine von Bayreuth: "L'Huomo" (1754). In: alte-musik-forum.de (visitor impressions 2009)

- Andrea Bernasconi, Wilhelmine Friederike Sophie, Robert Heger, Gilbert Gravina: The Triumph of Light | Allegorical festival in 1 act: [Historical performance material from the Bavarian State Opera. Performance material 1958]. OCLC 643220813 ( title recording of the Bavarian State Library )

- French translation l'homme see homme in the Wiktionary

See also

- For the title L'Huomo see L'homme. European Journal of Feminist History. Göttingen 1990 ff., ISSN 1016-362X

proof

- ↑ http://digital.bib-bvb.de/view/bvbmets/viewer.0.6.4.jsp?folder_id=0&dvs=1566593350291~190&pid=2556206&locale=de_DE&usePid1=true&usePid2=true

- ↑ See her Argomento (preface).

- ↑ Designation in the German libretto: "good" or "bad guardian angel" (later in the text only "good and bad angel").

- ^ Based on a contemporary German translation by the then director of the court opera Philipp Christian Cuno von Bassewitz. Italian-German libretto, Rostock University Library.

- ↑ See contents in the German libretto.

- ↑ German Libretto, pp. 15 and 16.

- ↑ So the translation in the German foreword.

- ^ Wording of the German libretto title.

- ↑ Anemon about Animia: "Cet autre moimême mais bien plus parfait que moi".

- ↑ See also Theater of the Enlightenment. (No longer available online.) In: frankreich-experte.de. Form INform, archived from the original on August 12, 2013 ; accessed on August 21, 2019 .

- ↑ This is shown by the dialogues in their coherent, linguistic-rhetorical quality.

- ↑ See the trilingual preface.

- ↑ Good and bad guardian angel is the designation of the Bayreuth court opera director Philipp Cuno Christian von Bassewitz in his German translation of the libretto.

- ↑ On the definition of male / female, especially in Giovanni Pico della Mirandola, see Gisela Bock: Women in European History. P. 14.

- ^ Animia for volatile love , 15th scene, German libretto, p. 43.

- ↑ See contents (= German foreword).

- ↑ L'Huomo , foreword.

- ↑ " Margravine Wilhelmine's Opera efforts deserve greatest historical interest ". Reinhard Wiesend : Margravine Wilhelmine and the opera. In: Galli Bibiena and the court of muses of Wilhelmine von Bayreuth. Prestel, Munich 1998, ISBN 3-7913-1963-9 , p. 94.

- ↑ Are women men or not? German version of 1618 of the Latin disputatio of 1595. In: Elisabeth Gössmann (Ed.): Whether the women are people or not? (= Archive for women's research in the history of philosophy and theology . Volume 4). 2., revised. and exp. Edition. iudicium, Munich 1996, ISBN 3-89129-004-7 , pp. 101-124; Commentary by Jörg Jungmayr, pp. 52–62.

- ↑ For example, Gisela Bock mentions the Salonière Madame d'Epinay, who was still thinking about the word l'homme in this direction in 1776 , which as such means man as such or - with article and - man, whereas woman - “une femme “- would be expressed with another root of the word. From which she deduced that women are not defined as human beings, but as the opposite sex . Bock p. 20.

- ↑ About the composer Andrea Bernasconi s. Daniela Sadgorski: Andrea Bernasconi and the opera at the Munich Kurfürstenhof 1753–1772. Herbert Uz Verlag, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-8316-4000-3 , in particular pp. 58 and 61.

- ↑ Modern scores of the cavatines. Furore Verlag, Kassel.

- ↑ H. Lommel in: Carl Clemen: The religions of the earth. 1949, p. 145.

- ↑ See argument in the libretto (French Urtext).

- ↑ Thomas Betzwieser (ed.): Opera concepts between Berlin and Bayreuth. The musical theater of the Margravine Wilhelmine. Lectures of the symposium on the occasion of the performance of 'L'Huomo' in the Margravial Opera House in Bayreuth on October 2nd, 2009 (= Thurnauer Schriften zum Musiktheater. Ban 31). Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg, 2016, ISBN 978-3-8260-5664-2 , pp. 195–221.

- ↑ Sigmund Theophil Staden was the son of the long-time Fürstlich-Culmbach-Bayreuth court organist Johann Staden, born in Kulmbach .

- ↑ The (only surviving) contemporary performance material for L'Huomo , the copy by a Bayreuth court copyist, belongs to the library of Wilhelmine's sister Philippine Charlotte von Prussia in the Herzog-August-Bibliothek . The fact that there is also Wilhelmine's harpsichord concerto in the handwriting of the same scribe indicates a special connection to the Bayreuth court.

- ↑ Princely Bayreuth Court Calendar 1755, Bayreuth University Library.

- ↑ Irene Hegen: New documents and reflections on the music history of the Wilhelmine era. 5. Wilhelmine's Arcadian Diploma. In: Peter Niedermüller, Reinhard Wiesend (Ed.) 2002, pp. 54–57.

- ^ Wilhelmine von Bayreuth: L'Huomo / L'Homme . Italian / French facsimile. In: Peter Niedermüller, Reinhard Wiesend (Ed.), 2002, pp. 27–205. Italian / German libretto: Rostock University Library: Communicated by Sabine Henze-Döhring. In: Dies .: The musical composition of the opera L'Huomo. (PDF; 2.8 MB) Lecture at the symposium on the occasion of the revival of L'Huomo: The Musical Theater of Margravine Wilhelmine, October 2, 2009, Bayreuth Art Museum. (No longer available online.) In: uni-marburg.de. December 1, 2009, p. 1 , archived from the original on November 7, 2016 ; Retrieved on August 21, 2019 (lecture text with footnotes).

- ↑ Bayreuther Zeitung. June 22, 1754, Bayreuth University Library.

- ^ Sabine Henze-Döhring: Friedrich the Great. Musician and monarch. Beck, Munich 2012, ISBN 978-3-406-63055-2 , p. 228, note 17.

- ↑ Count Lehndorff's diaries. The secret records of Queen Elisabeth Christine's Chamberlain. New edition of the edition from 1907 in the translation of the then editor Karl-Eduard Schmidt-Lötzen, ed. by Gisela Langfeld, Berlin 2012, ISBN 978-3-86368-050-3 .

- ↑ Performance material in the archive of the Bavarian State Opera in Munich.