Rigoletto

| Work data | |

|---|---|

| Title: | Rigoletto |

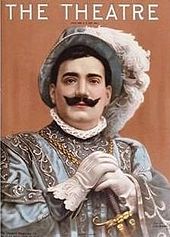

Poster announcing the premiere |

|

| Shape: | Opera in three acts |

| Original language: | Italian |

| Music: | Giuseppe Verdi |

| Libretto : | Francesco Maria Piave |

| Literary source: | Victor Hugo : Le roi s'amuse |

| Premiere: | March 11, 1851 |

| Place of premiere: | Venice , Teatro La Fenice |

| Playing time: | about 2 hours |

| Place and time of the action: | 16th century in Mantua , Italy |

| people | |

|

|

Rigoletto is an opera by Giuseppe Verdi that premiered in 1851 at the Teatro La Fenice in Venice. The libretto is by Francesco Maria Piave and is based on the melodrama Le roi s'amuse by Victor Hugo (1832). The opera was initially criticized by the censors ; Verdi and Piave therefore had to change the originally intended title La maledizione ( The Curse ) and relocate the scene from Paris to Mantua . The essential elements for Verdi, such as the crippled main character Rigoletto and the sack in which his dying daughter is put, have been preserved.

The opera is considered to be Verdi's first masterpiece and established his world fame. Verdi himself considered Rigoletto to be one of his most successful works and, unlike other Verdi operas, there are no revisions or new versions. Rigoletto was already an overwhelming success at the premiere and was performed in almost all European opera houses over the next few years. In the second half of the 19th century the libretto was often criticized as a “show piece” and the music as trivial “organ music”; Today, Rigoletto's position is undisputed by both the public and the experts. The opera has been part of the repertoire of many opera houses for over 160 years and is still one of the most frequently performed Italian operas, which is reflected not only in regular new productions , but also in a large number of recordings on sound and video carriers.

action

first act

First picture: In the palace of the Duke of Mantua

At a ball in his palace, the Duke of Mantua talks to the courtier Borsa about an unknown, beautiful town girl whom he has seen repeatedly in the church. The Duke turns to Countess Ceprano, whom he wants to win for himself ( Questa o quella ). His hunchbacked court jester Rigoletto mocks the countess's husband, whereupon the latter, supported by the other courtiers, swears vengeance. The courtier Marullo surprises the other courtiers with the news that Rigoletto has a lover ( Gran nuova! Gran nuova! ). When Rigoletto suggests to the Duke that Ceprano be arrested or beheaded in order to have a free run with the Countess, the courtiers decide to take revenge on Rigoletto. The Count of Monterone, whose daughter was dishonored by the Duke, appears at the festival to demand an account from the Duke. Monterone is rejected by him and is also mocked by Rigoletto ( Ch'io gli parli ). Monterone then curses the Duke and Rigoletto and is arrested.

Second picture: Dark cul-de-sac in front of Rigoletto's house

Rigoletto was deeply concerned about the curse. Now he rushes home to make sure that his daughter Gilda is safe ( Quel vecchio maledivami! ). In a dead end he meets the murderer Sparafucile, who offers him his services ( Un uom di spada sta ). Rigoletto refuses him, but asks where he can find Sparafucile if the worst comes to the worst.

Rigoletto recognizes parallels between himself and the murderer ( Pari siamo!… Io la lingua, egli ha il pugnale ). When he comes home ( Figlia!… - Mio padre! ), Gilda asks him about her origins and family. But he refuses to give her the information and does not even tell her his name ( Padre ti sono, e basti ). Rigoletto urges Gilda not to leave the house except for going to church. Giovanna, Gilda's companion, is warned to always keep the front door closed. Then he returns to the palace. The disguised duke has already snuck into Rigoletto's house and realizes that the stranger from the church is Rigoletto's daughter. He introduces himself to Gilda as a poor student and declares his love for her ( È il sol dell'anima, la vita è amore ). Meanwhile, in front of the house, the courtiers prepare to kidnap Gilda. Giovanna reports that footsteps can be heard outside, whereupon the Duke disappears through the back door.

Gilda looks after him pensively from her balcony ( Gualtier Maldè! ), But the masked courtiers stand ready with a ladder to kidnap Rigoletto's supposed lover. Rigoletto returns, driven by bad premonitions. The courtiers make him believe that they are about to kidnap Countess Ceprano. Rigoletto is masked, he is holding the ladder, which is not placed on Ceprano's house but on his own. Only when he hears Gilda's cry for help ( Soccorso, padre mio! ) Does he realize what is being played; he searches in vain for his daughter in his house (although he does not call out "Gilda, Gilda", as can be heard in several recordings and productions), and he remembers Monterone's curse again ( Ah, la maledizione ).

Second act

In the Duke's palace

In the palace, the Duke is upset that his new lover has been kidnapped ( Ella mi fu rapita!… Parmi veder le lagrime ). When the courtiers tell him they kidnapped her and brought her to his bedroom, he happily rushes to her. Rigoletto comes to the palace in search of Gilda and asks the courtiers who mock him ( Povero Rigoletto! ) For information about his daughter's fate. The courtiers are shocked when they learn that Gilda is Rigoletto's daughter, but they refuse him access to the duke, whereupon he insults her in a faint anger ( Cortigiani, vil razza dannata ).

Gilda comes out of the Duke's bedroom and throws herself into her father's arms ( Mio padre! - Dio! Mia Gilda! ). Rigoletto realizes that his daughter was not only kidnapped and dishonored, but also fell in love with the Duke. At that moment, Monterone is shown on the way to the dungeon. When Monterone complains that he has cursed the Duke in vain, Rigoletto swears revenge on the Duke ( Sì, vendetta, tremenda vendetta ).

Third act

Street in front of Sparafuciles house thirty days later

To dissuade his daughter from her love for the Duke, Rigoletto secretly visits the Sparafuciles tavern with her and shows her how the Duke in disguise ( La donna è mobile ) now ensnares Sparafucile's sister Maddalena ( Un dì, se ben rammentomi ). He sends his daughter, disguised as a man, to Verona and instructs Sparafucile (again without giving his real name: Egli è 'delitto', punizion 'son io - his name is' crime', my name is' punishment ' ) to Sparafucile, the Duke murder and hand over his body in a sack ( Venti scudi hai tu detto? ). When the murderer wants to carry out the act, his sister stands in his way and asks for the guest's life ( Somiglia un Apoll quel giovine… io l'amo ). After some hesitation, Sparafucile lets himself be changed and instead wants to murder the next man who walks in the door, because he has already received an advance payment for a corpse from Rigoletto. Gilda has overheard part of the conversation between Sparafucile and Maddalena, she decides to sacrifice her life for the Duke, who is still loved by her ( Io vo 'per la sua gettar la mia vita ). Already disguised as a man according to Rigoletto's instructions for the escape from Mantua, she goes into the tavern and is stabbed by Sparafucile during the height of a thunderstorm.

Rigoletto appears at midnight to collect the sack with the corpse. He already thinks that his revenge has been achieved ( Della vendetta alfin giunge l'istante! ) When he hears the Duke's voice in the distance. Rigoletto opens the body bag and holds his dying daughter in her arms. She asks her father for forgiveness, then she dies ( V'ho ingannato… colpevole fui… ). Rigoletto realizes that Monterone's curse was fulfilled not on the Duke but on him ( Ah, la maledizione ).

Emergence

templates

The libretto of Rigoletto is the verse drama Le roi s'amuse of Victor Hugo basis, which in turn to older models, like the 1831 published Vaudeville -Stück Le Bouffon du Prince ( The Fool Prince ) by Anne-Honoré-Joseph Duveyrier and Xavier -Boniface Saintine , falls back. In this play, essential elements of the plot are already laid out, but, according to the customs of melodrama, it ends well: The duke regrets his crimes and marries the niece of the fool Bambetto . With Le roi s'amuse, Hugo turned this material into a drama about the Renaissance King Francis I and his fool Triboulet with a clear political thrust and wanted to set a “literature of the people” against a “literature of the court”.

In a tense political situation (the failed July Revolution of 1830 , which resulted in the installation of the citizen king Louis-Philippe I , was still present to all those involved), it was no wonder that the play was premiered on November 22, 1832 a huge theatrical scandal. Hugo's supporters sang songs of mockery to the king in the stalls and answered the whistling concert of the royalist part of the audience by singing the Marseillaise . Eventually the performance turned into a big brawl, and the next day the police banned further performances of the play. The second performance took place in Paris on the 50th anniversary of this scandal on November 22, 1882, long after the Paris premiere of Rigoletto in 1856.

Verdi had read Hugo's drama for the first time in 1850 when he was looking for a subject for an opera that was planned for Venice at the La Fenice Theater the following year and was immediately enthusiastic about it, although he understood the meaning of Le roi s'amuse , which is only today is still known as a model by Rigoletto , far overestimated:

“Oh, Le roi s'amuse is the greatest material and perhaps even the greatest drama of modern times. Triboulet is worthy of Shakespeare's invention !! [...] When I went through Le roi s'amuse while looking through various subjects , it struck me like lightning, like a sudden illumination [...]. "

Verdi began writing this opera under the title La maledizione ( The Curse ) and postponed the planned (and later never executed) opera Re Lear . Francesco Maria Piave was commissioned to write the libretto, with whom Verdi had already performed in the operas Ernani (1844, also based on a drama by Hugo), I due Foscari (1844), Macbeth (1847), Il corsaro (1848) and Stiffelio (1850) had worked together.

The similarities between Hugo's drama and Piave's libretto are clear and much greater than in other dramas set by Verdi, which usually deviate very far from the original. The locations and proper names in drama and opera are different, but not only do the essential motifs and characters agree, but even the individual scenes. "With the exception of the Duke's aria at the beginning of the second act ('Ella mi fu rapita!'), All of the opera's 'numbers' have a direct equivalent in Hugo." Conversely, there are only two appearances in the drama without a counterpart in Verdi. The body bag in the final act, which Verdi had to argue about with the censorship authority, goes back to Hugo. Even more: Piave even adopted individual verses almost literally, the most famous of the opera's: La donna è mobile , which Hugo allegedly discovered in Chambord Castle and King Franz attributed: Souvent femme varie ...

Despite the great agreement with Hugo's original, the libretto deviates from it at crucial points, whereby it is astonishing "with what small changes in the exterior the differences in the interior are achieved." Piave and Verdi turn Hugo's political tendency into a largely apolitical, independent concept the following opera, which is not least reflected in the title: Despite the repeated changes to the title (from La maledizione to Il duca di Vendome to Rigoletto ), Hugo's original title Le roi s'amuse was never up for debate.

Confrontations with the censorship

While Verdi was still working on the last rehearsals for the Stiffelio in Trieste , he learned on November 11, 1850 from Carlo Marzari, the artistic director of the Teatro La Fenice , that the authorities had objections to the play and wanted to see the libretto. This was justified by the "rumor [...] according to which the drama Le roi s'amuse by Victor Hugo, on which the new work by Mr. Piave is based, had a negative reception both in Paris and in Germany. The reason for this was that Debauchery that drama is full of. Since the honorable nature of the poet and the maestro are known, the central management has confidence that the subject will be developed in the right way. She only asked for the libretto to be made sure of this. ”Such a reaction from the authorities in the Austrian-ruled Venice had to be expected after the events of 1832, but Piave seems to have misjudged the situation.

At this point, around four months before the planned premiere, this development was a catastrophe. On December 1, Marzari then announced to Verdi that the material had finally been rejected by the censorship authorities and that Piave's proposals to replace King Franz with a contemporary liege lord and to leave out some "debauchery" had not been accepted. Verdi, who was already in the middle of the composition, was angry about this decision (not least about the "idiot" Piave), but also desperate. He offered the Fenice to replace Stiffelio and to stage it personally in Venice. Now Piave proposed that La maledizione be reworked into Il duca di Vendôme . Verdi, however, did not agree with the associated changes, as they saw the character of the play and the protagonists being distorted; For example, he did not want to do without Triboulets hump and the body bag in the final scene. Verdi wrote to Mazari on December 14, 1850: “[…] an original, powerful drama has been turned into something completely banal and passionless. [...] as a conscientious artist, I cannot compose this libretto. "

The situation was thoroughly muddled when on December 29, 1850, Piave visited Verdi in his house in Busseto , where an agreement was reached the next day that was supposed to satisfy the composer, the theater and the censorship. Now the plot has been moved to Mantua, the main character has been renamed from Triboulet to Rigoletto, the title has been changed from Maledizione to Rigoletto and the historical King Franz has been changed to a fictional duke. The essential elements of the plot for Verdi - the main character ugly and disfigured, the curse and the sack - have been preserved. A scene in Act 2 was deleted in which the Duke uses a key to break into a room in the castle in which Gilda has locked himself. The censorship also required the change of some personal names that were too similar to real names. The discussion about alleged immorality or excesses of the piece was initially off the table.

On January 20, 1851, Verdi had almost finished composing the second act, but the official approval for the performance had not yet been received. It was not until January 26th that Piave was able to report the formal release of the piece to Busseto. Verdi completed the composition on February 5, and finally came to Venice himself on February 19 and took over the rehearsal work, for which only 20 days were available. In accordance with his working style, he had only completed the vocal parts, while he composed the orchestral parts in the course of the subsequent rehearsals.

Felice Varesi (1813–1889) as Rigoletto, Raffaele Mirate (1815–1885) as Herzog and Teresa Brambilla (1813–1895) as Gilda took on the leading roles for the premiere . The singers did not receive their scores until February 7th. According to a frequently repeated anecdote, Mirate only received his aria La donna è mobile the day before the premiere in order to prevent this train number from being distributed prematurely. In fact, the canzone is already included in the first sketches and in the original libretto; it was also rehearsed as normal.

From the beginning, Verdi's work on Rigoletto was characterized by a "certainty in all artistic decisions that had been rare even with Verdi". In contrast to other of his operas, such as Simon Boccanegra or Don Carlos , Verdi saw the work on Rigoletto as done after the premiere: Rigoletto has therefore neither been revised nor reworked. Verdi only seems to have been dissatisfied with the "key scene", which was deleted for reasons of censorship; on September 8, 1852, he wrote to Carlo Antonio Borsi that it was necessary "to show Gilda and the Duke in his bedroom". Verdi did not come back to this, however, the second act remained as it was.

Performance history

premiere

The world premiere of Rigoletto took place on March 11, 1851, the conductor was Gaetano Mares, the set was designed by Giuseppe Bertoja. The Fenice was with around 1,900 places at that time one of the largest opera houses in Italy and had a modern gas lighting as well as on the latest stage equipment, which was under the guidance of chief mechanic Luigi Caprara since 1844th This made it possible to implement Verdi's high demands on technology: “Thunder and lightning not [as usual] according to your mood […], but in time. I want the lightning bolts to light up on the stage background. "

For the world premiere of Rigoletto, Bertoja created Italy's first three-dimensional stage structures. Until then, stage sets consisted of painted prospectuses and backdrops that were moved as required. For the first time, elements such as stairs, terraces and balconies have been built for Rigoletto . “In the second picture of the first act, a large terrace protruding at the height of the first floor with a tree in front of a house was built in front of a house, in the third act a two-story tavern open to the auditorium on the ground floor. These structural elements formed separate playing levels that divided the stage dramatically. ”Set design and staging were so important to Verdi that he had commissioned Piave from Busseto to take care of the stage instructions and not the libretto. Only a few weeks before the performance, at a time when the opera had not even been orchestrated, Verdi's greatest concern was apparently its scenic effect.

The expected effects came about, and the premiere was a great triumph for Verdi, which was unexpected on this scale. Composer and singer were celebrated by the audience, the duet Rigoletto / Gilda from the first act and the duet Gilda / Herzog had to be repeated. During the Duke's aria in the third act, the audience is said to have become so enthusiastic that Raffaele Mirate could no longer begin with the second stanza. In the first performance review of the local press, however, objections to this new type of opera were already evident:

“Yesterday we were literally overrun with news: the novelty, or rather the peculiarity of the subject; the novelty of the music, its style, even the musical forms, and we have not yet been able to form a clear idea about it. [...] The composer or the poet was probably seized by a late love for the satanic school [...] by looking for the beautiful and ideal in the deformed and repulsive. I can't really praise this taste. Nevertheless, this opera achieved a great success, and the composer was celebrated, called, applauded after every number, and two of them even had to be repeated. "

distribution

From Venice, the opera spread very quickly over the stages in Italy: Bergamo, Treviso, Rome, Trieste and Verona followed in the same year. Due to censorship, the work in Italy was initially often performed under different titles and with mutilated content: In Rome (1851) and Bologna (1852) the opera was called Viscardello , in Naples Clara di Perth , in other places in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies Lionello . At a number of opera houses, with the intention of eliminating the “moral excesses” of the work, there were also curious changes in content: Sometimes the Duke and Gilda were not allowed to meet in church, sometimes the wife of Count Ceprano became his unmarried sister , and finally at the end of the opera Rigoletto did not exclaim “La maledizione” but “O clemenza di cielo”.

In 1852 Rigoletto was performed at a further 17 opera houses, in 1853 another 50 productions were added, including at La Scala in Milan , in Prague, London, Madrid, Stuttgart and St. Petersburg, and in 1854 another 29, including San Francisco, Odessa, Tbilisi and Munich . Rigoletto could not be seen in Paris until 1857: Victor Hugo, who viewed the opera as plagiarism , had prevented the performance for six years; it could only be enforced through a court ruling. In the first ten years after its premiere, Rigoletto was released on around 200 stages. Rigoletto was played everywhere there was theater , including in places that were rather exotic in terms of operatic tradition, such as Bombay (1865), Batavia, Calcutta or Manila (1867).

A theater scandal broke out on March 7, 1933 when Rigoletto was performed at the Semperoper in Dresden. The audience, consisting mainly of SA and NSDAP members, shouted down the conductor Fritz Busch , who was one of the protagonists of the “ Verdi Renaissance ” and who had made himself unpopular with the Nazi leadership, and prevented him from performing.

present

Rigoletto has been part of the standard repertoire since it was first performed, i.e. for over 160 years, and is now one of the most frequently performed works of every season. According to the Operabase , Rigoletto was ranked ninth among the most performed operas worldwide in the 2011/2012 season. For 2011–2013, 37 new productions were recorded worldwide.

It is no coincidence that the modern directorial theater takes on Rigoletto again and again : the metaphors of melodrama with its stark contrasts and drastic effects offer numerous opportunities for interpretation. For example with Hans Neuenfels , who settled Rigoletto in 1986 at the Deutsche Oper Berlin on a typified palm island, or Doris Dörrie , who put Rigoletto in 2005 in Munich on the planet of the apes and the court society in ape costumes; Stephen Landridge moved the work at the Vienna Volksoper into the film milieu of the 1950s; Thomas Krupa, in turn, moved Rigoletto to a doll's house in Freiburg in 2012. Jonathan Miller founded his own tradition of Rigoletto interpretations in New York in 1983 , which allows opera to be played in a mafia milieu, an idea that Kurt Horres took up in 1998 in Frankfurt and Wolfgang Dosch in Plauen in 2009. Michael Mayer, in turn, placed Rigoletto in 2013 in a new Met production in Las Vegas in the 1960s - in the "Sinatra style". In 2013 Robert Carsen continued the series of relocating opera to more or less contemporary milieus at the festival in Aix-en-Provence, choosing the circus world around 1830.

On the other hand, there have been more historical productions, for example at the New York Metropolitan Opera in 1977 by Kirk Browning or in 1989 by Otto Schenk , in Europe for example the lavish productions by Sandro Sequi at the Vienna State Opera , which has been there since 1983 Repertoire, or that of Gilbert Deflo, which has been played at La Scala in Milan since 1994. Such "costume battles", which stand out from the directorial theater, were also seen in film adaptations of the opera, for example in 1983 under the direction of Jean-Pierre Ponnelles and under the direction of Riccardo Chailly or in the live staging recorded in 2010 at "Original locations in Mantua" under Zubin Mehta with Plácido Domingo in the title role in a supposedly "authentic setting" (in fact, the setting in Mantua is fictional and was enforced by the censors).

libretto

reception

As popular as Rigoletto was with the audience from the start, the libretto and the music met with strong rejection from critics and musicians alike - an attitude that only gave way to a differentiated assessment in the middle of the 20th century. The music critic Hermann Kretzmar said in 1919: "With works like Rigoletto [...] the main impression is [...] regret over the musical talent that has been thrown out in disgusting stories like this." The subject matter and libretto of Rigoletto became long in this way Time devalued as “nonsense”, “show piece” or “ Kolportage ” and not understood as typical of the genre. “Disgusting stories” also meant the characters and the constellation of the protagonists - the people on the fringes of society, cripples, pimps, whores on the one hand and the depraved, amoral court society on the other - who do not come into the usual opera world seem to fit. Last but not least, the play does not have a positive hero, but as the main character has an extremely contradicting personality: As a cynical, devious court jester, Rigoletto is no less unscrupulous in the first act than his boss - still under the impression of Monterone's curse and full of fear for his daughter, he takes part in the next outrage, the (alleged) kidnapping of Countess Ceprano, and in the final act, his revenge is more important to him than bringing his daughter to safety. Not only Rigoletto is contradictory: “[...] the Duke of Verdi is not just portrayed as a stately bon vivant who carelessly takes all rights. The music also portrays him as capable of true feelings [...] ”. And "[...] even sweet Gilda is not entirely made of one piece: the vice has touched her. She forgives her seducer (tacitly apologizing for his sin) and commits suicide to save him. All the characters are contradicting, unexpectedly against the grain. "

The Piaves libretto was also repeatedly criticized for its obvious inconsistencies and improbabilities: The fact that Count Ceprano's palace and the court jester's house are next to each other on the same street is not very credible, and this is also the most unsuitable place to hide a daughter to keep. It also seems improbable that Rigoletto, although he returns at the end of the first act due to bad premonitions, does not become suspicious of the kidnapping in front of his own house; In the second act, Monterone is led across the palace to the dungeon for no good reason; Finally, Sparafucile, although presented as a professional killer, carries out the murder so bungled that Gilda “can crawl out of her body bag and explain everything to her father in detail”.

Of course, some inconsistencies can be traced back to changes brought about by the censorship. In order to mitigate alleged "debauchery", corrections were made that defuse and falsify the original libretto to this day. In the original text of the third act (scene 11, bar 33), the Duke asks Sparafucile "two things, immediately [...] your sister and wine"; In the published score, on the other hand, it says: "two things, immediately ... a room and wine" - so the Duke has been going to the brothel since then to rent a room. Rigoletto's subsequent attempt to convince Gilda of the wickedness of her lover: “Son questi i suoi costumi” (“These are his customs” - scene 11, bars 33-35), is no longer quite understandable.

Verdi always ignored objections to Rigoletto's libretto , as in other of his operas (especially later with Il Trovatore ). A “realistic”, logically fully coherent course of action was not his concern, he was concerned with the effect on the stage and the coherence of the characters. As in the French melodrama, which is also an indirect model for Rigoletto via Le roi s'amuse , it is about stark, theatrical opposites (here: the disfigured court jester and the beautiful daughter, the depraved court society and the loving father, the ducal palace and the Spelunke) and events that enable effective plot changes: an unexpected reunion and recovery, powerful people who threaten innocent victims, danger, persecution, finally (in which Hugo no longer follows the genre) salvation, purification and a happy ending. Rigoletto's appearance is by no means superficial in this context - Verdi decidedly set himself apart from a view that was still widespread in the middle of the 19th century, which inferred from physical deficits to character deficits - a view that a hunchbacked fool as the main character alone already considers Scandal had to understand: “A hunchback who sings! some will say. So what? […] I think it's very nice to portray an extremely misshapen and ridiculous person who is passionate and filled with love inside. "(Verdi to Piave)

Subject

After the failure of the revolution of 1848 , Verdi initially turned away from political issues. The compositional reorientation, in which Verdi "found new dramaturgical concepts tried and tested and more subtle means of expression, was combined with a fundamental change in the subject as well ." The focus was now on "interpersonal conflicts within the manageable framework of the bourgeois family". The family forms the “model for a suitable socio-political constitution”. In Rigoletto , this position is exemplarily presented in the duet of the second picture in an emphatic phrase: “Culto, famiglia, la patria, il mio universo è in te!”: The values of Rigoletto's patriarchal world are “metaphysically exaggerated” and focused in his Daughter, the incarnation of his life plan. A passage “takes up the force and tension of the famous Hebrew choir from Nabucco (1842), apparently unchanged [...]. Only the former collective emotion is now the exaggerated expression of an individual. It is no longer about the affirmation of a current political will of the people, but about the spectacularly exaggerated gesture of a father […] ”. In this opera, as in the others of this period, Verdi no longer addresses the ideals of the Risorgimento , but rather the family as a patriarchal, conservative social model and the forces that oppose its realization.

Verdi repeatedly took up the constellation father - daughter , already in his first opera Oberto , then in Nabucco , Luisa Miller and Stiffelio (Stankar - Lisa), in the later works in La forza del destino , especially in Simon Boccanegra (Simon - Amelia , Fiesco - Maria) and finally again in Aida .

music

reception

Despite Rigoletto's great popularity and his music, in particular the arias Caro nome or La donna è mobile (numbers that are now also known outside of opera and such as the so-called prisoners' choir from Nabucco , the triumphal march from Aida or Che gelida manina from Puccini's La Bohème widely regarded as typical of Italian opera), not only Piave's libretto but also Verdi's music was controversial for a long time. Many contemporaries saw the music of Rigoletto as superficial, shallow and melodious, as "organ music ", not in spite of, but often precisely because of its popularity. In Italy this criticism was brought forward in particular by artists who saw themselves as avant-garde and who had gathered between 1860 and 1880 in the Scapigliatura group , to which the later Verdi librettist Arrigo Boito also belonged. In Germany, objections to the music of Rigoletto were raised in particular by Richard Wagner's supporters or circles close to him; Wagner and Verdi were considered antipodes, especially in the second half of the 19th century. Shortly after the premiere of Rigoletto , the Hannoversche Zeitung wrote :

“The music doesn't give in to the text in terms of meanness. Only the parts that move in the waltz, gallop, Scottish and polka are sensually alluring. A hint of spirituality or cosiness can only be sensed in Gilda's little aria 'Expensive Name, Its Sound' and in the duet between Rigoletto and Sparafucile. Otherwise there is a lack of spirit, of every inkling that the composer understood what an opera could be and therefore should be. "

The Frankfurter Nachrichten , which, eight years after the premiere, could already assume that Verdi's so-called mistakes and virtues were known, was only slightly more friendly :

“It is well known that the work has all the flaws and all the virtues of Verdian music, light, pleasing dance rhythms in the most hideous scenes, that death and ruin, as in all works by the composer, pass through gallops and cottillons [sic!]. But the opera contains a lot of beautiful and good things and is sure to remain in our repertoire. "

The Viennese music critic Eduard Hanslick (a Verdi and Wagner critic) said: “Verdi's music has just as ominous an effect on the art of singing as it does on modern Italian composition.” Hanslick criticized a “thick, noisy instrumentalization” and superficial effects. The critic considered the weakest thing in Rigoletto to be the “flirtatious, cold figure of Gilda; their 'bravura aria from the Styrian Alps' and the prancing 'Addio' in the love duet seemed 'downright funny' to Hanslick ”.

With the "Verdi renaissance" of the 1920s and increasingly in the 1950s, a differentiated view began. The alleged superficiality, the shortcomings or the alleged simplicity of the instrumentation were now understood as an "expression of naturalness and (of) dramatic immediacy". Significantly, not only conductors and singers interested in the audience-effective performance material, but also a number of “avant-garde” composers spoke for Rigoletto's music , such as Luigi Dallapiccola , Luciano Berio , Ernst Krenek , Wolfgang Fortner , Dieter Schnebel and earlier Igor Stravinsky , who said polemically: "... I claim that, for example, in the aria 'La donna è mobile', in which the elite saw only pitiful superficiality, there is more substance and more true feeling than in the rhetorical torrent of tetralogy."

Conception

From a musical point of view, Rigoletto is a new kind of work, which the composer himself regarded as "revolutionary". Here Verdi begins to dissolve the traditional number opera and replace it with a well-composed structure. “Formally, the new is the consistent dramatic and musical development in the sense of that image-sound composition with its 'continuous music', which, for example, was partially successful in Macbeth .” Music and plot push each other forward; apart from the duke's traditional arias, “time never stands still” in Rigoletto . Even the great “love duet” in the second picture is sung almost hastily (Allegro, then Vivacissimo), the duke and Gilda only need 132 bars to get closer.

How the (remaining) “numbers” are integrated into the flow of the plot becomes particularly clear in Gilda's still conventional and only aria Caronome (which, tellingly , is based on a wrongly given name, i.e. a lie): Already at the end of the previous one Number the courtiers in front of the house have started the preparations for the kidnapping (scene Che m'ami, deh, ripetimi ... ), they continue this throughout the aria, and at the end of the aria the courtiers are also finished (scene È là ... - Miratela ); the kidnapping could take place now, if Rigoletto did not intervene at that moment, which leads directly to the next scene ( Riedo!… perché? ).

In terms of the flow of action, Verdi conceived Rigoletto as a "sequence of duets". They, not the arias, form the core of the work, especially the three duets between Rigoletto and Gilda, which are spread over the three acts. The famous quartet in the third act also consists of two parallel duets, one inside the house (Duca and Maddalena) and one outside (Rigoletto and Gilda). In the final duet of the third act, the voices do not combine; Rigoletto and the dying Gilda, who is no longer part of Rigoletto's world, only sing alternately, as in the first act Rigoletto and Sparafucile (Verdi takes up the duet between Astolfo and Rustighello from Gaetano Donizetti's Lucrezia Borgia ). This duet between Rigoletto and Sparafucile has "always been praised as a special masterpiece by Verdi and [is] certainly the most unconventional piece of the entire opera." In the "concentration on dark colors and chamber music subtlety" it suggests a kind of self-talk by Rigoletto, the one in Sparafucile to a certain extent meets his other self.

Since the core of the opera is a "sequence of duets", the main character Rigoletto does not have an aria in the conventional sense: Pari siamo at the beginning of the 2nd image is a fully composed recitative as a preparation for the first major duet with Gilda, and also Cortigiani in the 2nd The act is referred to as an aria in the score, but is fully integrated into the course of the plot, both scenically and musically; both numbers therefore rarely find their way into the request concert or on sampler . There are a number of conventional numbers in Rigoletto , but as such they fulfill a dramatic purpose in that they are assigned to the court society, i.e. the duke and the choir (initially also Gilda), who are thus musically explicitly identified as representatives of the conventional and traditional become. With this juxtaposition of opposites, the basic concept of melodrama is also taken up in the musical structure. Rigoletto is thus also a work of transition from the traditional number opera to a music-dramatic, uniform structure, as Verdi realized much later in Otello . In this respect, the work is a hybrid opera, whereby Verdi does not simply juxtapose the two forms, but instead organically integrates them into his dramatic concept.

This concept is not only implemented by Verdi in the formal structure: The criticism of the “organ music” was aimed particularly at the “Hm-Ta-Ta music”, such as in the Duke's well-known arias or in the courtiers' choir in the first and second act actually sounds. However, this is part of Verdi's dramatic conception, because the catchy, but undemanding melody of the “street hype” La donna è mobile is used to characterize the lust for pleasure and superficiality of court society, so it is deliberately designed to be trivial. For those who did not notice it right away, Verdi then cites this piece twice in this sense - the second time as the triumph of the banal over Rigoletto's oath of vengeance. The "villain" does not rumble here with drums and trumpets, but cheers happily to himself, and he escapes the curse directed at him.

When Verdi works with motifs in Rigoletto , this differs significantly from the technique of leitmotifs used by Wagner : “Of course, unlike Wagner, it is not about leitmotifs that set a leading example, but rather about memories and emotional connections. “The curse motif already determines the prelude in C minor (on a single pitch, the C, in slow crescendo and in double-dotted rhythm); it reappears at Monterone's appearance and then whenever Rigoletto remembers this curse, that is, up to the last bar. Another motif, which rhythmically catches Rigoletto's limping gait, accompanies his appearance at the end of the first act (number 7, from bar 8) or in the second act (number 9). “Verdi's dotted rhythms acquire a new dramatic meaning; the coincidence of music and gesture occurs. "

In this way, the tempi are also integrated into the compositional architecture: “Isn't it a tragic irony that the same tempo for Gilda's aria 'Caro nome' (where she expresses her love for Duca in disguise) and Rigoletto's 'Larà, lalà' ( where Rigoletto tries in the deepest desperation to disguise himself in front of the courtiers in order to look for Gilda's footsteps)? Or isn't a musical and dramaturgical arc drawn out when Gilda's aria has the same tempo as her later story about the encounter with the Duca ('tutte le fest') and also 'Cortigiani', Rigoletto's outburst against the courtiers? ”Accordingly, Verdi has the work provided with detailed tempo indications, but this did not prevent it from “becoming a tradition to systematically disregard this. Tempo indications are not a matter of taste, but architectural, shape-defining parameters. "

Realization - quartet and trio

The musical highlight of the opera is the third act, in which the opposites that have previously been built up collide and lead to catastrophe, especially the quartet Un dì, se ben rammentomi ... Bella figlia dell'amore , incidentally the only piece not even that Victor Hugo wanted to deny his recognition. Each person in this quartet brings their own musical characterization: the Duke, who takes the lead and tries to seduce Maddalena with sweeping lyrical melodies; Maddalena with staccato eighth notes, in which she mocks the duke's promises (the - after all, married - incognito duke is promising her marriage), but who seems to be less and less averse as the scene progresses; Gilda and Rigoletto, on the other hand, who remain outside the house observing, initially with long pauses and only occasional objections, Gilda then increasingly desperate, Rigoletto, who "expresses his anger from time to time in slowly progressing, weighty phrases" and towards the end of the quartet impatiently urges to leave because he realizes that eavesdropping on the Duke in the dive bar was probably not such a good idea after all.

The implementation of these diverse intentions of Verdi is also demanding in terms of singing and cannot be heard in every performance or recording: “It is inimitable how Caruso […] concludes the short solo Bella figlia dell'amore on the word consolar with a brilliant group end a sound figure that becomes a visible gesture and congenially captures the ambiguity of the situation, the erotic advertising of a 'macho': Caruso manages to sing with an emphatic sound - to seduce Maddalena - and at the same time the emphasis as played, as erotic empty phrases to expose. "

If the quartet still adheres to traditional forms, the subsequent “scene, trio and thunderstorm” ( Scena, Terzetto e Tempesta ) evades the previous norms “... the entire third act from the beginning of the storm [is] unprecedented ”. Completely different from the thunderstorm music in Gioachino Rossini's ( The Barber of Seville or La Cenerentola ), the thunderstorm does not form a musical insert between acts or scenes, but is - with strings in the lower register, insertions of oboe and piccolo, but above all with the characteristic, humming choir voices behind the stage - fully integrated into the plot. It underlies the entire scene with a tense background noise of increasing intensity: first of all for the cynical dialogue between Sparafucile and Maddalena about the appropriate murder victim (Maddalena suggests killing Rigoletto for the sake of simplicity), which flows seamlessly into the trio in which the desperate Gilda den makes a crazy decision to finally discard her father's (secret) plan of life (she is very well aware of this: “perdona o padre!”) and to have herself killed for his mortal enemy, the beloved who she has long forgotten.

“The central thunderstorm scene is like a sound film, where the moving images show an external and internal drama. The scurrying movements of the people in the irregularly flashed darkness are pervaded by empty fifths, pale string tremolos, briefly flickering wind sequences, thunder and an eerily groaning humming chorus, and they mean both external and internal processes: at the moment of the strongest clap of thunder, murder happens. In this scene, the music changes again and again from halting recitative to flowing ariosis, always when feelings become melody, like when the duke falls asleep with the warbler on his lips, as Maddalena begins to rave about her 'beautiful Apollo', then in the actual trio passages, where Maddalena asks for the life of the one she loves and in Gilda the feeling matures that she is sacrificing herself for her beloved. "

Numbers

first act

- No. 1. Orchestral Prelude - Andante sostenuto, C minor

- No. 2. Introduction

- Introduction: Della mia bella incognita borghese (Duca, Borsa) - Allegro con brio, A flat major

- Ballad: Questa o quella per me pari sono (Duca) - Allegretto, A flat major

- Minuet and Perigordino: Partite? ... crudele! (Duca, Contessa, Rigoletto, Chor, Borsa) - Tempo di Minuetto, A flat major

- Choir: Gran nuova! Gran nuova! (Marullo, Duca, Rigoletto, Ceprano, Chor) - Allegro con brio

- Scene: Ch'io gli parli (Monterone, Duca, Rigoletto, Chor) - Sostenuto assai, C minor, F minor

- Stretta: Oh tu che la festa audace hai turbato (all except Rigoletto) - Vivace, D flat minor

- No. 3. Duet: Quel vecchio maledivami! ... Signor? (Rigoletto, Sparafucile) - Andante mosso, D minor

- No. 4. Scene and duet (Rigoletto, Gilda)

- Scene: Quel vecchio maledivami! … Pari siamo! … Io la lingua, egli ha il pugnale (Rigoletto) - Adagio, D minor

- Scene: Figlia! … - Mio padre! (Rigoletto, Gilda) - Allegro vivo, C major

- Duet: Deh, non parlare al misero (Rigoletto, Gilda) - Andante, A flat major

- Cabaletta: Veglia, o donna, questo fiore (Rigoletto, Gilda, Giovanna, Duca) - Allegro moderato assai, C minor

- No. 5. Scene and Duetto (Gilda, Duca)

- Scene: Giovanna, ho dei rimorsi ... (Gilda, Giovanna, Duca) - Allegro Assai moderato, C major, G major,

- Scene: T'amo! (Gilda, Duca) - Allegro vivo, G major

- Duet: È il sol dell'anima, la vita è amore (Duca, Gilda) - Andantino, B flat major

- Scene: Che m'ami, deh, ripetimi… (Duca, Gilda, Ceprano, Borsa, Giovanna) - Allegro, B flat major

- Cabaletta: Addio… speranza ed anima (Gilda, Duca) - Vivacissimo, D flat major

- No. 6. Aria and scene

- Aria: Gualtier Maldè! … Caro nome che il mio cor (Gilda) - Allegro moderato, E major

- Scene: È là… - Miratela (Borsa, Ceprano, choir) - Allegro moderato, E major

- No. 7. Finale I.

- Scene: Riedo! … Perché? (Rigoletto, Borsa, Ceprano, Marullo) - Andante assai mosso, A flat major

- Choir: Zitti, zitti, muoviamo a vendetta (choir) - Allegro, E flat major

- Stretta: Soccorso, padre mio! (Gilda, Rigoletto, Chor) - Allegro assai vivo

Second act

- No. 8th scene

- Scene: Ella mi fu rapita! (Duca) - Allegro agitato assai, F major / D minor

- Aria: Parmi veder le lagrime (Duca) - Adagio, G flat major

- Scene: Duca, Duca! - ebb? (Chorus, Duca) - Allegro vivo, A major

- Choir: Scorrendo uniti remota via (chorus) - Allegro assai moderato

- Cabaletta: Possente amor mi chiama (Duca, choir) - Allegro, D major

- No. 9th scene

- Scene: Povero Rigoletto! (Marullo, Ceprano, Rigoletto, Paggio, Borsa, Chor) - Allegro moderato assai, E minor

- Aria: Cortigiani, vil razza dannata (Rigoletto) - Andante mosso agitato, C minor, F minor, D flat major

- No. 10th scene and duet (Rigoletto, Gilda)

- Scene: Mio padre! - Dio! Mia Gilda! (Gilda, Rigoletto, choir) - Allegro assai vivo ed agitato, D flat major

- Duet: Tutte le fest al tempio (Gilda, Rigoletto) - Andantino, E minor, A flat major, C major, D flat major

- Scene: Compiuto pur quanto a fare mi resta (Rigoletto, Gilda, Usciere, Monterone) - Moderato, A flat major

- Cabaletta: Sì, vendetta, tremenda vendetta (Rigoletto, Gilda) - Allegro vivo, A flat major

Third act

- No. 11. Scene and Canzone

- Scene: E l'ami? - Semper (Rigoletto, Gilda, Duca, Sparafucile) - Adagio, A minor

- Canzone: La donna è mobile (Duca) - Allegretto, B major

- Recitativo: È là il vostr'uomo ... (Sparafucile, Rigoletto)

- No. 12. Quartet

- Scene: Un dì, se ben rammentomi (Duca, Maddalena, Rigoletto, Gilda) - Allegro, E major

- Quartetto: Bella figlia dell'amore (Duca, Maddalena, Rigoletto, Gilda) - Andante, D flat major

- Recitativo: M'odi, ritorna a casa… (Rigoletto, Gilda) - Allegro, A minor

- No. 13th scene, trio, thunderstorm

- Scene: Venti scudi hai tu detto? (Rigoletto, Sparafucile, Duca, Gilda, Maddalena) - Allegro, B minor

- Trio : Somiglia un Apollo quel giovine… (Maddalena, Gilda, Sparafucile) - Allegro, B minor

- thunderstorm

- No. 14 Scene and Finale II

- Scene: Della vendetta alfin giunge l'istante! (Rigoletto, Sparafucile, Gilda) - Allegro, A major

- Duet V'ho ingannato… colpevole fui… (Gilda, Rigoletto) - Andante, D flat major

Roles and voices

| role | Voice type | Vocal range | First cast, March 11, 1851 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rigoletto, court jester | baritone | B-g 1 | Felice Varesi |

| Gilda, Rigoletto's daughter | soprano | h – c 3 | Teresa Brambilla |

| Duke of Mantua | tenor | c – h 1 | Raffaele Mirate |

| Sparafucile, contract killer | bass | F – f sharp 1 | Paolo Damini |

| Maddalena, Sparafuciles sister | Mezzo-soprano | h – f sharp 2 | Annetta Casaloni |

| Giovanna, Gilda's governess | Old | f 1 –es 2 | Laura Saini |

| Count Ceprano | bass | G sharp – f 1 | Andrea Bellini |

| Countess Ceprano | Mezzo-soprano | as 1 –es 2 | Luigia Morselli |

| Matteo Borsa, courtier | tenor | c – a 1 | Angelo Zuliani |

| Count Monterone | baritone | B-f 1 | Feliciano Ponz |

| Marullo | baritone | H-f 1 | Francesco De Kunnerth |

| Bailiff | tenor | Giovanni Rizzi | |

| Page of the Duchess | Mezzo-soprano | g – d 1 | Annetta Modes Lovati |

| Male choir: courtiers | |||

instrumentation

- Woodwinds : two flutes (the second also piccolo ), two oboes (the second also English horn ), two clarinets , two bassoons

- Brass : four horns , two trumpets , three trombones , cimbasso

- Timpani , percussion : bass drum and cymbals

- Strings : violins , viola , cellos and double basses

- Incidental music : Banda

- Big drum backstage

Edits

Due to the great popularity of the opera and its rapid spread, there was soon a need for reproductions, in the time before the invention of the phonograph , especially for musical arrangements for solo instruments, which enabled them to be played in concerts, but also as part of domestic music . As early as 1853, Anton Diabelli wrote three potpourri [s] based on motifs from the opera: Rigoletto by G. Verdi. For pianoforte and violin concertant (op 130). Also known were a Rigoletto Fantasy by Karl and Franz Doppler for two flutes and piano, as well as a Rigoletto Fantasy for two clarinets and basset horn (op. 38), as well as an arrangement by the guitar virtuoso Johann Kaspar Mertz .

The Verdi paraphrases and transcripts by Franz Liszt , including the quartet's concert paraphrase from the third act of 1859, have survived to the present day .

Discography

The clash of opposing moments, which is so important in Rigoletto's dramatic conception, affects not only the libretto and music, but also the immediate events on the stage, right down to the individual props : the arrangement of orchestra and incidental music, Rigoletto's hump, Sparafucile's sword in the second picture, mask and ladder in Gilda's kidnapping, the inside and outside in the quartet and trio of the third act and finally the sack in the final scene are essential visual elements. The fact that they are missing in the sound recordings is in the nature of things, "... it is only worrying how seldom this loss is also perceived as a defect" - the "disgusting story" of the stage is thus superseded by the concertante character of the sound recording. The recordings “... consequently reflect the changes in the art of Italian opera singing much more often than approaches for a dramaturgical mastery of Victor Hugo's and Giuseppe Verdi's piece.” Rigoletto's recordings are therefore not infrequently merely a platform for the presentation of singing stars - a “dramaturgically convincing cast” of the three main roles is anything but trivial and the result is “more of a rare stroke of luck than the rule”.

However, this did not stand in the way of an extensive discography. For the period between 1907 and 2009, Operadis recorded 190 complete recordings, 115 of which were live recordings. By 1939 there were ten, between 1940 and 1950 another 15. There was a plethora of recordings in the 1950s, when new recording techniques not only extended the playing time of the sound carriers, but also for the first time real "music productions" (not only mere reproductions). Between 1950 and 1959 there were 31, between 1960 and 1969 another 36, and between 1970 and 1979 another 33 recordings; since then the number has decreased somewhat: 1980–1989: 23, 1990–1999: 14 and 2000–2009: 26; Since the early 1980s, many vinyl recordings have been digitized on CD, so that the annual Rigoletto output was in some cases significantly higher. Five recordings were made in English, twelve in German and one each in Russian, Bulgarian and Hungarian, the last production in German in 1971 under Siegfried Kurz with the Dresden Staatskapelle , Ingvar Wixell in the title role, Anneliese Rothenberger (Gilda) and Róbert Ilosfalvy (Herzog ). Since 1983 the recordings have only been produced in the Italian original language. Further changes in the music market can be seen in the fact that no studio productions have been made since 1996 and that newer recordings, such as those under Nello Santi (2002) or those under Fabio Luisi (2010), are only published on DVD, i.e. no longer as pure sound carriers were.

Historical recordings

Recordings of Rigoletto or individual numbers from this opera have existed since professional sound recordings were made. The aria “Questa o quella” from the first act can already be found with piano accompaniment on Enrico Caruso's legendary first recording (still on cylinder) from 1902. Other well-known interpreters of numbers from Rigoletto were Giovanni Martinelli , Giacomo Lauri-Volpi (both Herzog), Titta Ruffo , Giuseppe De Luca , Pasquale Amato (Rigoletto), Marcella Sembrich , Luisa Tetrazzini or Lily Pons (Gilda) in the early days of sound recording . 78 records with the quartet from the third act by Rigoletto and the sextet from Lucia di Lammermoor on the reverse were part of the basic equipment of a record collection in the 1920s and 1930s. Almost all of these recordings are now available on CD.

Rigoletto is one of the first operas to be recorded in full on vinyl. The work was recorded completely for the first time in 1912 (in French), for which a total of 25 records were required; With a total playing time of almost two hours, it had to be changed every four to five minutes. 1915–1918 the first recording was made in Italian, with Antonio Armentano Anticorona, Angela De Angelis and Fernando de Lucia in the leading roles on 18 double-sided 78 mm records.

The inadequate recording technology in the era of acoustic sound recording (until around 1925, no microphones were used for this , but a horn, in front of which singers and orchestra crowded), however, falsifies the listening impression not insignificantly: “... while with the quartet from the fourth [sic! recte: third act of Rigoletto the voice of Caruso - the tenor's spectrum is between 200 and 700 Hz - has been captured in all its fullness and color, the voices of Marcella Sembrich (1908), Luisa Tetrazzini (1912) and Amelita sound Galli-Curci (1917) like colorless whistling tones. ”Apart from these technical deficiencies, the numerous historical recordings allow an overview of meanwhile around two thirds of the interpretation history of Rigoletto and thus also of changes in the understanding of this opera, as far as this is expressed in the singing.

Role portraits on CD

Rigoletto

Rigoletto's first sound recordings were made at a time that was stylistically shaped by verismo and his expressive singing style, at that time the contemporary music genre in Italian opera. The “old school” still oriented towards bel canto, as it is echoed in the Rigoletto interpretations by Giuseppe de Luca, Mattia Battistini or Victor Maurel , are an exception to this trend. The outstanding singer of Rigoletto was Titta Ruffo at the beginning of the 20th century , who made her debut in this role at La Scala in 1904. There is also no complete recording of him, but his interpretation is preserved in individual recordings in all major scenes of the opera. Jürgen Kesting analyzes how Ruffo designs the role :

“... you experience [...] a nuanced, expressive role portrait. It is not the portrait of a sensitive father, but of a 'damned soul' (Celletti) who is not only a victim, but also an angel of vengeance. 'Pari siamo' sounds with brooding intensity, 'Deh non parlare al misero' (1912 with Finzi-Magrini) sounds restrained and obscured by the shadowing of the voice and less by the reduction in dynamics. Ruffo also sings 'Piangi, fanciulla' with a full, but not loud voice, which literally explodes with 'Cortigiani'. Ruffo tones the contrasting episode from 'Miei signori perdono, pietate' on with painful pathos, but the phrase 'Tutto al mondo è tal figlia per me' and 'Ridate a me la figlia' not only sound like the lamenting suffering of the father, but the Severity of the threat of vengeance. Few singers have sung the carelessness of 'La rà, la rà' in front of the great invective as eloquently as Ruffo. […] 'Vindice avrai' is notated on CC in the score. But already at the premiere, the baritone Varesi went to the E-flat and kept it on forever. With the last of his breath he went into the cabaletta in a quasi-choked voice. At the same point, Victor Maurel sang with Messa di voce , also on the Eb . Ruffo sings the id to the full, diminishes and changes to 'Sì, vendetta' with a quiet, vibrating voice. The effect is great (especially since 'avrai' is not senselessly overstretched, as with many others later), and with the phrase 'Come un fulmine scagliato da Dio' you experience the eruption of a volcano. "

Ruffo's interpretation continued to shape the style into the age of the long-playing record. At the beginning of the 1950s, not only were the recording techniques improved, but also new artistic paths were explored, for example by reviving the traditions of bel canto . During this era, alongside Leonard Warren , Gino Bechi , Ettore Bastianini and Giuseppe Taddei , and in particular Tito Gobbi and Robert Merrill, there were defining role portraits: “... the title character, split between wit and pathos, parlando and cantilena, cynicism and love, has not yet come closer [1986] than Merrill. ”Gobbi made up for vocal limits with his ability to express himself, for example in Rigoletto's monologue“ Pari siamo ”:

“… The sound is dark and brooding, 'Io la lingua' comes with desperate sarcasm, 'egli ha il pugnale' with brutal anger. 'Che ride' shows with gestural clarity how desperate laughter can be. He puts the fearful 'Quel vecchio maledivami' on a finely spun legato, swelling in an exemplary fashion. Accentuating the / i / of 'maledivami': it is the moment in which 'la maledizione' (the leitmotif of the opera) becomes, as it were, a trauma. He concisely forms the sixteenths of the accented phrases 'O uom ini', 'o nat u ra' and 'vil sceller a to'. Every word gets its inflection, its color, its expression, every phrase its tension, every exclamation its urgency. "

Even if the Rigoletto is part of the standard repertoire of baritones today, not every interpreter succeeds in covering the lyrical-Belcantist as well as the dramatic sides of the role. The demands are great: "The Rigoletto voice therefore needs fragility as much as grandiosity, bright mobility as well as baritone force". Even well-known singers like Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau , Leo Nucci or Plácido Domingo were or are controversial in this role.

Gilda

A different kind of change can be seen in the conception of Gilda's role. At the beginning of the 20th century, Gilda was seen primarily as an enthusiastic girl, as an innocent seduced and finally as a foolish victim: “... a girl of extreme simplicity "Purity and Innocence" Accordingly, in the early days of the recordings, the role was primarily occupied with "light" voices, with soprani leggeri , that is, coloratura sopranos like Marcella Sembrich, Luisa Tetrazzini or Erna Berger . Toti dal Monte , who sang Gilda in a production from 1922 under Arturo Toscanini at La Scala, was for a long time considered the ideal Gilda. Her “ethereal singing” provided the “untouchable, girlish, crystalline” that was expected from this part.

However, this direction of interpretation obscures another dimension: Gilda is by no means the “innocent girl” that may be heard in “Caronome” (according to the Verdian logic of opposites); The extent to which there is agreement between her and the Duke remains open in the final version (after deleting the "key scene"). All three duets with Rigoletto show a Gilda who opposes her father, his life plan or his "life lie" and his patriarchal canon of values, until she finally decides to destroy the father's plans, an understanding of roles that is with the means of the coloratura soprano is no longer feasible: “For this role, the interpreter of Gilda needs deep human sensitivity, empathy and understanding; therefore I cannot understand why this part is often entrusted to a soprano leggiero . Gilda values love so much that she is ready to sacrifice her life for it. To kill the Duke would mean to kill their ideal of love. "

In this sense, Toscanini cast the Gilda in 1944 in a departure from the decades-long practice with Zinka Milanov , that is, with a dramatic soprano who was best known as La Gioconda , Aida or Leonora (in Il Trovatore ); a CD recording of the third act of this production has been preserved. However, this line-up met with clear rejection, so that this direction of interpretation remained an episode for the time being.

At the beginning of the 1950s, Maria Callas , who had both types of voices, changed her view of this role. Callas only sang Gilda twice on stage, there is a recording of a performance from 1952 (in Mexico City under Umberto Mugnai with Piero Campolonghi as Rigoletto and Giuseppe Di Stefano as Duke) and a studio production from 1955 (under Tullio Serafin ) on CD, with Tito Gobbi only being an adequate partner in the studio production. The role portrait, which was not only explained to Callas fans among experts like Jürgen Kesting (“Callas develops the part like no other interpreter, sings at the beginning with her magical little girl's voice, unfolds an exemplary legato in a duet with Rigoletto,… In 'tutte le fest 'and in the duet' Piangi, fanciulla piangi 'suddenly a whole new voice can be heard, a sound soaked in sorrow and pain ”) or John Ardoin is seen as a“ milestone in the history of interpretation ”:“ Gilda's soprano spinto is at least open On the instrumental side of the medal, no one was more ingenious than Maria Callas… “From the 1960s onwards, voices were preferred for recordings of the opera, if available, that could also implement the dramatic aspect beyond coloratura security, for example Joan Sutherland , Renata Scotto or Ileana Cotrubaș .

duke

Since Caruso, the duke's role has been a parade role for tenors. Not least because of the simply structured train numbers such as “La donna e mobile”, however, the demands on the game are often underestimated. The mixture of emphasis, machismo and cynicism calls for the singers to be able to express themselves: “However, not everyone was able to match Verdi's intended characterization with vocal elegance.” The part is also technically demanding: “It not only requires a large volume and a slight ability to extend up to Db and D, but also singing 'on the breath' in many passages that lie in the so-called passagio region. ” Alfredo Kraus , Carlo Bergonzi and Luciano Pavarotti have stated in interviews that they consider this part to be the most difficult of Verdi's tenor roles.

After Caruso, Beniamino Gigli and Tito Schipa were able to distinguish themselves in the role of Duke; in their interpretations they "combined veristic mannerisms with impressive mezzavoce of the old Italian school". Well-known representatives of the role after the Second World War included Jussi Björling and Carlo Bergonzi , Alfredo Kraus, who played the role a total of fourteen times, had a lasting impact on the role: “In 1960 he sang the Duke under Gavazzeni , 1963 under Georg Solti - and sang both times he made him better, and above all more complete, than any of his rivals. ”The recording from 1971 with Luciano Pavarotti should also be emphasized ; it “offers an exemplary interpretation - even if it may not meet all expectations.” In contrast, interpretations by singers such as Giuseppe Di Stefano , Franco Corelli or Mario del Monaco , who used an “athletic singing style”, no longer correspond to today's listening habits.

Complete recordings (selection)

(Conductor; Rigoletto, Gilda, Herzog, Sparafucile, Maddalena; label)

- 1912; François Ruhlmann, Jean Noté, Aline Vallandri, Robert Lassalle, Pierre Dupré, Ketty Lapeyrette; Audio Encyclopedia, (CD 1999)

- 1944; Arturo Toscanini ; Leonard Warren , Zinka Milanov , Jan Peerce , Nicola Moscona, Nan Merriman; RCA / Urania (3rd act only)

- 1954; Angelo Questa; Giuseppe Taddei , Lina Pagliughi , Ferruccio Tagliavini , Giulio Neri, Irma Colasanti; Warner-Fonit

- 1955; Tullio Serafin ; Tito Gobbi , Maria Callas , Giuseppe Di Stefano , Nicola Zaccaria , Adriana Lazzarini; EMI

- 1956; Ionel Perlea ; Robert Merrill , Roberta Peters , Jussi Björling , Giorgio Tozzi ; Naxos

- 1956; Mario Rossi, Josef Metternich , Mimi Coertse , Libero De Luca, Gottlob Frick , Ira Malaniuk , Walhall - WLCD0193

- 1960; Gianandrea Gavazzeni ; Ettore Bastianini , Renata Scotto , Alfredo Kraus , Ivo Vinco, Fiorenza Cossotto ; BMG

- 1961; Nino Sanzogno; Cornell MacNeil , Joan Sutherland , Renato Cioni , Cesare Siepi , Stefania Malagu; Decca

- 1963; Georg Solti ; Robert Merrill, Anna Moffo , Alfredo Kraus, Ezio Flagello , Rosalind Elias ; RCA

- 1964; Rafael Kubelík ; Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau , Renata Scotto, Carlo Bergonzi , Ivo Vinco, Fiorenza Cossotto; Deutsche Grammophon

- 1967; Francesco Molinari-Pradelli ; Cornell MacNeil, Reri Grist , Nicolai Gedda , Agostino Ferrin, Anna di Stasio; EMI

- 1971; Richard Bonynge ; Sherrill Milnes , Joan Sutherland, Luciano Pavarotti , Martti Talvela , Huguette Tourangeau ; Decca

- 1977; Francesco Molinari-Pradelli; Rolando Panerai , Margherita Rinaldi, Franco Bonisolli , Bengt Rundgren, Viorica Cortez; Arts Music

- 1978; Julius Rudel ; Sherrill Milnes, Beverly Sills , Alfredo Kraus, Samuel Ramey , Mignon Dunn; EMI

- 1979; Carlo Maria Giulini ; Piero Cappuccilli , Ileana Cotrubaș , Plácido Domingo , Nikolaj Gjaurow , Elena Obraztsova ; Deutsche Grammophon

- 1984; Giuseppe Sinopoli ; Renato Bruson , Edita Gruberová , Neil Shicoff , Robert Lloyd , Brigitte Fassbaender ; Decca

- 1989; Riccardo Chailly ; Leo Nucci , June Anderson , Luciano Pavarotti, Nikolaj Gjaurow , Shirley Verrett ; Decca

- 1993; James Levine ; Vladimir Chernov , Cheryl Studer , Luciano Pavarotti, Roberto Scandiuzzi , Denyce Graves; Deutsche Grammophon

- 2000; Mark Elder ; John Rawnsley, Helen Field, Arthur Davies, John Tomlinson , Jean Rigby; Chandos

Film adaptations (selection)

- Rigoletto (1946) - directed by Carmine Gallone, conductor: Tullio Serafin, singers: Tito Gobbi, Lina Pagliughi, Mario Filippeschi, Giulio Neri

- Rigoletto (1977) - directed by Kirk Browning, conductor: James Levine, singers: Cornell MacNeil, Ileana Cotrubaș, Placido Domingo

- Rigoletto (1983) - directed by Jean-Pierre Ponnelle, conductor: Riccardo Chailly, singers: Ingvar Wixell , Edita Gruberova, Luciano Pavarotti, Ferruccio Furlanetto

- Rigoletto (1995) - Directed by Barry Purves (animation)

- Rigoletto (2000) - directed by David McVikar, conductor: Edward Downes, singers: Paolo Gavanelli, Christine Schäfer , Marcelo Álvarez

- Rigoletto (2002) - directed by Gilbert Deflo, conductor: Nello Santi, singers: Leo Nucci, Elena Mosuc, Piotr Beczala

- Giuseppe Verdi's Rigoletto Story (2005) - director: Gianfranco Fozzi, conductor: Keri-Lynn Wilson, singers: Roberto Servile, Inva Mula , Marcelo Álvarez, duration: 126 minutes

- Rigoletto (2008) - director: Nikolaus Lehnhoff, conductor: Fabio Luisi , singers: Zeljko Lučić, Diana Damrau , Juan Diego Flórez

Rigoletto in film and television

Due to its great popularity, Rigoletto is often a synonym for opera in general (or even for “ Italianità ” or Italian way of life in the broadest sense and is quoted accordingly in films, for example). In the German crime film “The Hour of Temptation” from 1936, directed by Paul Wegener , with Gustav Fröhlich , Lída Baarová and Harald Paulsen , a visit to the opera with a Rigoletto performance forms the framework. In Bernardo Bertolucci's 1976 film epic Novecento ( 1900 ) , a drunken hunchback disguised as Rigoletto introduces the second episode with the exclamation “Verdi is dead”. The quartet from Act 3 by Rigoletto is at the center of the British feature film Quartet (2012) directed by Dustin Hoffman . The film, based on a play by Ronald Harwood , tells the story of former singers and musicians who want to save their retirement home from financial ruin through a Verdi gala that will focus on the quartet.

Advertising also occasionally uses Rigoletto , for example a 1992 commercial for Nestlé's Choco Crossies with a quote from the aria La donna è mobile , as did Dr. Oetker 2006 for the Pizza Ristorante .

literature

grades

- The Partitur publisher is: G. Ricordi & CSpA, Milan.

- Rigoletto. Vocal score. Edition C. F. Peters, Frankfurt 2010, ISBN 979-0-01-400983-0 .

libretto

- Kurt Pahlen, Rosemarie König: Giuseppe Verdi: Rigoletto. Text book. Italian German. 5th edition. Schott, Mainz 2003, ISBN 3-254-08025-4 .

- Giuseppe Verdi: Rigoletto. German Italian. Reclam, Stuttgart 1998, ISBN 3-15-009704-5 .

Secondary literature

- Daniel Brandenburg: Verdi - Rigoletto. Bärenreiter, Kassel 2012, ISBN 978-3-7618-2225-8 .

- Julian Budden: Verdi - life and work. 2nd revised edition. Reclam, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-15-010469-6 .

- Attila Csampai , Dietmar Holland (ed.): Giuseppe Verdi, Rigoletto (= rororo non-fiction book. No. 7487; rororo opera books). Rowohlt, Reinbek 1982, ISBN 3-499-17487-1 .

- Rolf Fath: Reclam's Little Verdi Opera Guide . Reclam, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-15-018077-5 .

- Leo Karl Gerhartz: Rigoletto. In: Piper's Encyclopedia of Musical Theater. Volume 6, Piper, Munich / Zurich 1986, ISBN 3-492-02421-1 , pp. 432-439.

- Egon Voss: Rigoletto. In: Anselm Gerhard, Uwe Schweikert (ed.): Verdi manual. Bärenreiter, Kassel 2001, ISBN 3-7618-2017-8 , p. 386 ff.

Web links

- Rigoletto : Sheet Music and Audio Files in the International Music Score Library Project

- Libretto (Italian), Venice 1850. Digitized version of the Munich digitization center

- Rigoletto (Giuseppe Verdi) in the Corago information system of the University of Bologna

- Work information and libretto (Italian) as full text on librettidopera.it

- Plot and libretto of it at Opera Guide landing page for URL upgrade currently unavailable

- Discography of Rigoletto at Operadis

Individual evidence

- ^ Leo Karl Gerhartz: Rigoletto. In: Piper's Encyclopedia of Musical Theater. Volume 6, Piper, Munich / Zurich 1986, p. 437.

- ↑ Christian Springer: Verdi and the interpreters of his time. Holzhausen, Vienna 2000, ISBN 3-85493-029-1 , p. 235.

- ^ Leo Karl Gerhartz: Of pictures and signs. In: A. Csampai, D. Holland (Eds.): Giuseppe Verdi, Rigoletto Rowohlt, Reinbek 1982, p. 15.

- ^ Leo Karl Gerhartz: Rigoletto. In: Piper's Encyclopedia of Musical Theater. Volume 6, Piper, Munich / Zurich 1986, p. 435.

- ^ Leo Karl Gerhartz: Of pictures and signs. In: Csampai, Holland (ed.): Giuseppe Verdi, Rigoletto. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1982, p. 11.

- ^ Daniel Brandenburg: Verdi - Rigoletto. Bärenreiter, Kassel 2012, p. 19

- ↑ quoted from Leo Karl Gerhartz: From images and signs. In: Csampai, Holland (ed.): Giuseppe Verdi, Rigoletto. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1982, p. 25

- ↑ Verdi's letter to Piave, January 31, 1851, quoted from: Daniel Brandenburg: Verdi - Rigoletto. Bärenreiter, Kassel 2012, p. 28 f.

- ↑ Verdi's letter to Piave, January 31, 1851, quoted from: Daniel Brandenburg: Verdi - Rigoletto. Bärenreiter, Kassel 2012, p. 31.

- ^ Leo Karl Gerhartz: Of pictures and signs. In: Csampai, Holland (ed.): Giuseppe Verdi, Rigoletto. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1982, p. 15 f.

- ^ Leo Karl Gerhartz: Of pictures and signs. In: Csampai, Holland (ed.): Giuseppe Verdi, Rigoletto. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1982, p. 17 f.

- ^ Leo Karl Gerhartz: Of pictures and signs. In: Csampai, Holland (ed.): Giuseppe Verdi, Rigoletto. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1982, p. 15.

- ^ A b Egon Voss: Rigoletto. In: Anselm Gerhard, Uwe Schweikert (ed.): Verdi manual. Bärenreiter, Kassel 2001, p. 388.

- ↑ Franco Abiati: The masterpiece of revenge. In: Giuseppe Verdi, Rigoletto. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1982, p. 147 f.

- ↑ Christian Springer: Verdi and the interpreters of his time. Holzhausen, Vienna 2000, p. 187.

- ↑ Franco Abiati: The masterpiece of revenge. In: Giuseppe Verdi, Rigoletto. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1982, p. 148 f.

- ↑ Christian Springer: Verdi and the interpreters of his time. Holzhausen, Vienna 2000, p. 187 f.

- ↑ Christian Springer: Verdi and the interpreters of his time. Holzhausen, Vienna 2000, p. 188 f.

- ↑ Christian Springer: Verdi and the interpreters of his time. Holzhausen, Vienna 2000, p. 188.

- ↑ Christian Springer: Verdi and the interpreters of his time. Holzhausen, Vienna 2000, p. 189.

- ↑ Christian Springer: Verdi and the interpreters of his time. Holzhausen, Vienna 2000, p. 190.

- ^ Leo Karl Gerhartz: A memorable first performance in the Teatro La Venice in Venice. In: Csampai, Holland: Giuseppe Verdi, Rigoletto. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1982, p. 168.

- ↑ Detailed information on the singers at the premiere by Christian Springer: Verdi and the interpreters of his time. Holzhausen, Wien 2000, p. 123 ff. And p. 190 ff.

- ^ Leo Karl Gerhartz: A memorable first performance in the Teatro La Venice in Venice. In: Csampai, Holland: Giuseppe Verdi, Rigoletto. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1982, p. 174 f.

- ↑ See e.g. B. Wilhelm Zentner (Ed.): Rigoletto: Opera in 4 Aufz. (= Reclams Universal Library. No. 4256). Reclam, Stuttgart 1959, introduction to the German text of Rigoletto p. 7.

- ↑ Christian Springer: Verdi and the interpreters of his time. Holzhausen, Vienna 2000, p. 193.

- ^ Leo Karl Gerhartz: Rigoletto. In: Piper's Encyclopedia of Musical Theater. Volume 6, Piper, Munich / Zurich 1986, p. 433.

- ^ Egon Voss: Rigoletto. In: Anselm Gerhard, Uwe Schweikert (ed.): Verdi manual. Bärenreiter, Kassel 2001, p. 390.

- ↑ Verdi's letter to Piave, January 31, 1851, quoted from: Daniel Brandenburg: Verdi - Rigoletto. Bärenreiter, Kassel 2012, p. 93.

- ↑ a b Christian Springer: On the interpretation of Verdi's works. In: Verdi Studies: Verdi in Vienna, Hanslick versus Verdi, Verdi and Wagner, on the interpretation of Verdi's works, Re Lear - Shakespeare in Verdi. Edition Praesens, Vienna 2005, ISBN 3-7069-0292-3 , p. 248.

- ↑ Christian Springer: On the interpretation of Verdi's works. In: Verdi Studies. Edition Praesens, Vienna 2005, p. 250.

- ^ Leo Karl Gerhartz: A memorable first performance in the Teatro La Venice in Venice. In: Csampai, Holland: Giuseppe Verdi, Rigoletto. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1982, p. 174 f.

- ^ Daniel Brandenburg: Verdi - Rigoletto. Bärenreiter, Kassel 2012, p. 82.

- ^ Daniel Brandenburg: Verdi - Rigoletto. Bärenreiter, Kassel 2012, p. 98.

- ^ Daniel Brandenburg: Verdi - Rigoletto. Bärenreiter, Kassel 2012, p. 100.

- ^ Rolf Fath: Reclam's Kleiner Verdi-Opernführer , Reclam, Stuttgart 2000, p. 93.

- ^ Daniel Brandenburg: Verdi - Rigoletto. Bärenreiter, Kassel 2012, p. 97.

- ^ Justice for the conductor Fritz Busch , Die Welt, February 24, 2009 , accessed on March 7, 2013.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Leo Karl Gerhartz: Rigoletto. In: Piper's Encyclopedia of Musical Theater. Volume 6, Piper, Munich / Zurich 1986, p. 438.

- ^ Leo Karl Gerhartz: Rigoletto. In: Piper's Encyclopedia of Musical Theater. Volume 6, Piper, Munich / Zurich 1986, p. 438.

- ^ Daniel Brandenburg: Verdi - Rigoletto. Bärenreiter, Kassel 2012, p. 102.

- ↑ Ljubiša Tošic: Opera noise of the "sweet" life , discussion of the production in DER STANDARD, October 18, 2009, accessed on June 2, 2013.

- ↑ Alexander Dick: Gilda or a Puppenhaus - Verdi's "Rigoletto" at the Freiburg Theater Review of the production in Badische Zeitung, March 19, 2012, accessed on June 2, 2013.

- ↑ Men in Mafia Masquerade mobilize , discussion of the production in Frankfurter Allgemeine Sonntagszeitung, September 2, 2001, accessed on June 2, 2013.

- ↑ Ingrid Schenke: Rigoletto: hated mask, loving father , review of the staging in Vogtland-Anzeiger, Plauen (no year), accessed on June 2, 2013.

- ^ Anthony Tommasini: Bringing the Sinatra Style Out in 'Rigoletto'. Review of Michael Mayer's production at the Met. In: New York Times. January 29, 2013, accessed February 28, 2013.

- ↑ Frieder Reininghaus: Rigoletto in der Sommerfrische , discussion in Deutschlandradio Kultur on July 5, 2013, accessed on July 27, 2013

- ^ Daniel Brandenburg: Verdi - Rigoletto. Bärenreiter, Kassel 2012, p. 104

- ^ Daniel Brandenburg: Verdi - Rigoletto. Bärenreiter, Kassel 2012, p. 121.

- ^ "Rigoletto in Mantua" - and on ZDF: live staging of the Verdi opera at the original location. With world star Plácido Domingo. ZDF press release from September 1, 2010, accessed on December 28, 2012.

- ↑ a b c Dieter Schnebel: " Ah, la maledizione" - The breakthrough to the true tone and the tone of truth. In: Csampai, Holland: Giuseppe Verdi, Rigoletto. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1982, p. 244 ff.

- ^ William Weaver: Rigoletto's path of fate. In: Supplement to CD Rigoletto under Richard Bonynge, Decca 1983, p. 24.

- ^ Leo Karl Gerhartz: Of pictures and signs. In: Csampai, Holland (ed.): Giuseppe Verdi, Rigoletto. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1982, p. 9

- ^ Leo Karl Gerhartz: Of pictures and signs. In: Csampai, Holland (ed.): Giuseppe Verdi, Rigoletto. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1982, p. 9 f.

- ^ Luigi Dallapiccola: diary sheets. In: Csampai, Holland (ed.): Giuseppe Verdi, Rigoletto. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1982, p. 197; for example in the Ricordi score

- ^ Kurt Malisch: Il trovatore. In: Piper's Encyclopedia of Musical Theater. Volume 6, Piper, Munich / Zurich 1986, p. 442.

- ^ Leo Karl Gerhartz: Of pictures and signs. In: Csampai, Holland (ed.): Giuseppe Verdi, Rigoletto. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1982, p. 13.

- ^ Leo Karl Gerhartz: Of pictures and signs. In: Csampai, Holland (ed.): Giuseppe Verdi, Rigoletto. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1982, p. 11 and p. 15

- ^ Daniel Brandenburg: Verdi - Rigoletto. Bärenreiter, Kassel 2012, p. 36

- ↑ a b Jürgen Schläder: The patriarchal family. Simon Boccanegra and Verdi's philosophy of history. In: Bavarian State Opera Program 1995: Giuseppe Verdi - Simon Boccanegra. P. 30 f.

- ^ Sabine Henze-Döhring: Verdi's operas, a musical work guide. Original edition, Beck, Munich 2013, ISBN 3-406-64606-9 , p. 44.

- ^ A b Leo Karl Gerhartz: Rigoletto. In: Piper's Encyclopedia of Musical Theater. Volume 6, Piper, Munich / Zurich 1986, p. 436.

- ↑ Jürgen Schläder: The patriarchal family. Simon Boccanegra and Verdi's philosophy of history. In: Bavarian State Opera Program 1995: Giuseppe Verdi - Simon Boccanegra. P. 32.

- ^ Christian Springer: Simon Boccanegra, Documents - Materials - Texts. Praesens, Vienna 2007, p. 227