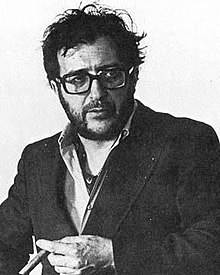

Luciano Berio

Luciano Berio (born October 24, 1925 in Oneglia ; † May 27, 2003 in Rome ) was an Italian composer , known for his experimental compositions and as one of the pioneers of electronic music .

Life

Berio was born into a musical family in the Ligurian coastal town of Oneglia. Both his father and grandfather were organists and taught him to play the piano . During the Second World War he was drafted into the army, but injured his hand with a rifle on the first day. He spent time in a military hospital and eventually fled to join a resistance group.

After the war, Berio studied at the Milan Conservatory with Giulio Cesare Paribeni (1891–1964) and Giorgio Federico Ghedini . Hindered from playing the piano by the injured hand, he concentrated on the composition. In 1947 the first public performance of one of his works took place, a suite for piano.

At that time Berio was earning his living accompanying singing classes; he met the American soprano Cathy Berberian . They married shortly after graduating from university in 1950 (they divorced in 1964).

In 1951 Berio went to the United States to study in Tanglewood with Luigi Dallapiccola , who aroused his interest in serial music . Bruno Maderna took him to the Darmstadt Summer Courses for New Music , which he attended from 1954 to 1959. There he met Pierre Boulez , Karlheinz Stockhausen , György Ligeti and Mauricio Kagel . He began to be interested in electronic music and founded the Studio di Fonologia Musicale , a studio for electronic music, with Bruno Maderna in Milan in 1955 . He invited a number of important composers to work here, including Henri Pousseur and John Cage . He also edited an electronic music magazine, Incontri Musicali .

In 1960 Berio returned to Tanglewood as “Composer in Residence” and in 1962, at the invitation of Darius Milhaud, accepted a teaching position at Mills College in Oakland (California) . In 1965 he began teaching at the Juilliard School , where he founded the Juilliard Ensemble , which is dedicated to performing contemporary music . In the same year he married for the second time.

Meanwhile, Berio worked steadily on his compositions. In 1966 he won the Prix Italia for Laborintus II , in 1968 his most famous work, the Sinfonia , premiered with great success .

In 1972 Berio returned to Italy. From 1974 to 1980 he was director of the electroacoustics department at IRCAM in Paris. In 1977 he married for the third time (his second marriage had been divorced in 1971). In 1987 he founded Tempo Reale in Florence , a center with a similar focus to IRCAM. In 1988 he was awarded an Antonio Feltrinelli Prize .

From 1994 to 2000 he was "Distinguished Composer in Residence" at Harvard . He was also elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1994. In 1985 he was accepted as an honorary foreign member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters .

Luciano Berio died in Rome in 2003 , leaving behind his second wife, Susan Oyama, as well as his third wife Talia Pecker Berio, two daughters Cristina and Marina Berio, three sons Stefano, Dani and Yoni Berio and four grandchildren.

music

Most of Berio's electronic works originate from his time at Studio di Fonologia in Milan. One of his most influential works from this period is Thema (Omaggio a Joyce) from 1958, in which Cathy Berberian reads from James Joyce's Ulysses . In a later work, Visage (1961), Berio created wordless emotional language by arranging fragments of a recording of Berberian's voice.

In 1968 Berio completed O King . There are two versions of this composition, one for voice, flute , clarinet , violin , violoncello and piano , the other for eight voices and orchestra. The piece is dedicated to the memory of Martin Luther King , who had been assassinated little before.

Shortly after its completion, the orchestral version of O King was integrated into the Sinfonia (1968–69) for orchestra and eight voices. The voices are not used in the traditional way; the singers are amplified by microphones, except for singing rhythmic or free speech and whispering is required. Berio uses text material from a wide variety of sources, such as Claude Lévi-Strauss ' Le cru et le cuit , Samuel Beckett's The Unnameable , performance instructions from various scores, solmization and Scat syllables, or comments on musical quotations that are currently being heard. The third movement is particularly well known; here Berio takes the third movement from Mahler's Second Symphony and lets the orchestra play a slightly shortened and newly arranged version of it. At the same time, different voices recite texts from different sources, and the orchestra plays quotes from Claude Debussy , Arnold Schönberg and others. This creates a dense collage . The result is a work with the usual scheme of tension and dissolution in classical music - using a completely new language. At any point in time, the actually used chords and melodies play a subordinate role compared to the fact that one hears a certain quote from Mahler, Alban Berg or Beckett. Because of this, the phrase is often considered to be one of the earliest examples of postmodernism in music. It has also been described as a deconstruction of Mahler's Second Symphony, much like Visage was a deconstruction of Berberian's voice.

A-Ronne , from 1975, also uses the collage technique, but focuses more on the voices. It is a piece for eight voices and an optional piano part. The work is one of a series of collaborations with the poet Edoardo Sanguineti , who created a text for her full of quotations from the Bible , TS Eliots and Karl Marx .

Not all of Berio's works cite the works of others. Perhaps the most famous among those for whom this is not the case is the series of compositions for solo instruments under the name Sequenze . Sequence I was written in 1958 and is for transverse flute , the last Sequence XIV , for violoncello , was completed in 2002. The common characteristic of these works is that they seek to explore the possibilities of the instrument and often require new playing techniques. Thus, in the technically difficult piecesequence XI from 1988, various playing techniques of the guitar are combined.

Berio was known for adapting and transforming the music of others, but he also subjected his own works to this process: the Sequenze series was the starting point for a series of works called Chemins , each based on the Sequenze . Chemins II (1967), for example, takes the originalsequence VI for viola and adapts it for viola and nine other instruments. With the addition of further instruments, further derivatives emerged, Chemins IIb , Chemins IIc and Chemins III . The names of the derived works do not necessarily follow this pattern, for example Corale from 1981 is based onsequence VIII for solo violin.

In addition to independent work, Berio undertook a number of arrangements of older works, including works by Claudio Monteverdi , Henry Purcell , Johannes Brahms and Gustav Mahler . For Berberian he wrote Folk Songs (1964) and (1967) arrangements of three songs by John Lennon and Paul McCartney . His completion of Giacomo Puccini's opera Turandot (premiered on May 25, 2002 in Los Angeles ( Kent Nagano )) also belongs in this context ; In his orchestral piece Rendering (1989) he completed the few sketches that Franz Schubert left for his Symphony No. 10 with his own music derived from other works by Schubert.

Berio's other compositions include Circles (1960) and Recital I (for Cathy) (1972), both written for Berberian, and a number of stage works, of which Un re in ascolto , written in collaboration with Italo Calvino , is probably the best known .

Works

- Opus Number Zoo, children's opera 1951; 1970 with texts by Rhoda Levine for five wind instruments, 1981 revised version.

- Author (Omaggio a Joyce), 1958

- Sequenze I – XIV, 1958–2002 for solo instrument

- Sequence I, 1958

- Circles, 1960

- Visage, 1961

- Passaggio (messa in scena), 1961–1962

- Folk Songs, 1964

- Chemins I – VII, 1965–1996 for solo instrument and ensemble / chamber orchestra

- Laborintus II; the work earned him the 1966 Prix Italia a

- Gesti, 1966 (work for alto recorder solo)

- Chemins II, 1967

- O King, 1968

- Sinfonia, 1968, dedicated to Leonard Bernstein ; Commissioned work for the New York Philharmonic , world premiere with them and the Swingle Singers in 1968 under Berio's direction. World premiere of the final five-movement version in 1969 at the Donaueschinger Musiktage with the Südwestfunk-Orchester under Ernest Bour .

- Recital I (for Cathy), 1972

- A-Ronne, 1975

- Coro, 1975-1976

- Quattro versioni originali della "Ritirata notturna di Madrid", 1975 (after Luigi Boccherini )

- Corale, 1981

- Un re in ascolto, world premiere at the Salzburg Festival 1984 under Lorin Maazel

- Call (St. Louis Fanfare), 1985/1987

- Sequence XI, 1988 for solo guitar (recorded for example in 1996 by Franz Halász)

- Ofanìm, 1988 (rev. 1997)

- Concerto II "Echoing Curves", 1988/89 (based on the drafts of the 10th Symphony in D major, D936a, by Franz Schubert)

- Rendering, 1989/90

- Outis, 1996

- Cronaca del luogo, 1999

- Altra voce, 1999

- Sequence XIV, 2002 for violoncello

- Punch, 2003; German premiere: Musikfest Berlin 2010

bibliography

- Peter Altmann, Sinfonia by Luciano Berio. An analytical study , Vienna, Universal Edition, 1977.

- AA.VV., "Sequenze per Luciano Berio" , Milano, BMG Ricordi 2000, ISBN 8875926859 .

- Luciano Berio "Un ricordo al futuro" ( Lezioni americane ), Torino, Einaudi, 2006. ISBN 88-06-13993-2

- Gianmario Borio, musical avant-garde around 1960. Draft of a theory of informal music , Laaber, Laaber Verlag 1993.

- Ute Brüdermann, The Musiktheater by Luciano Berio , Bern / Frankfurt / New York, Peter Lang 2007, ISBN 3-631-54004-3 .

- Rossana Dalmonte, Luciano Berio. Intervista sulla musica , Bari, Edizioni Laterza 1981.

- Claudia Sabine Di Luzio, polyphony and variety of meanings in the music theater by Luciano Berio , Mainz, Schott 2010.

- Norbert Dressen, language and music with Luciano Berio. Investigations into his vocal work , Regensburg, Bosse 1982, ISBN 3-7649-2258-3 .

- Giordano Ferrari, Les débuts du théâtre musical d'avantgarde en Italie , Paris, L'Harmattan 2000.

- Thomas Gartmann, "... that nothing in itself is ever completed." Studies on the instrumental work of Luciano Berio , Paul Haupt, Bern / Stuttgart / Vienna 1995; 2nd edition 1997, ISBN 3-258-05646-3 .

- René Karlen / Sabine Stampfli (edd.), Luciano Berio. Music manuscripts , (= "Inventories of the Paul Sacher Foundation", vol. 2), Basel (Paul Sacher Foundation) 1988.

- Jürgen Maehder , quotation, collage, palimpsest - On the text basis of music theater with Luciano Berio and Sylvano Bussotti , in: Hermann Danuser / Matthias Kassel (edd.), Musiktheater heute. International symposium of the Paul Sacher Foundation Basel 2001 , Mainz, Schott 2003, pp. 97-133.

- Jürgen Maehder , Giacomo Puccini's »Turandot« and its changes - The supplementary attempts of the III. "Turandot" file , in: Thomas Bremer / Titus Heydenreich (edd.), Zibaldone. Journal of Contemporary Italian Culture , vol. 35, Tübingen, Stauffenburg 2003, pp. 50-77.

- Florivaldo Menezes, Un essai sur la composition verbale électronique "Visage" de Luciano Berio , (= "Quaderni di Musica / Realtà", vol. 30), Modena 1993.

- Florivaldo Menezes, Luciano Berio et la phonologie. Une approche jakobsonienne de son œuvre , Frankfurt / Bern / New York, Peter Lang 1993.

- Fiamma Nicolodi, Pensiero e giuoco nel teatro di Luciano Berio , in: Fiamma Nicolodi, Orizzonti musicali italo-europei 1860-1980 , Roma, Bulzoni 1990, pp. 299-316.

- David Osmond-Smith, Playing on Words. A Guide to Berio's "Sinfonia" , London (Royal Musical Association) 1985.

- David Osmond-Smith (ed.), Luciano Berio. Two interviews with Rossana Dalmonte and Bálint András Varga , New York / London 1985.

- David Osmond-Smith, Berio , (= Oxford Studies of Composers, vol. 24), Oxford / New York, Oxford University Press 1991.

- David Osmond-Smith, Nella festa tutto? Structure and Dramaturgy in Luciano Berio's "La vera storia" , in: Cambridge Opera Journal 9/1997, pp. 281-294.

- David Osmond-Smith, Here comes nobody: a dramaturgical exploration of Luciano Berio's "Outis" , in: Cambridge Opera Journal 12/2000, pp. 163-178.

- Michel Philippot, Entretien Luciano Berio , in: La Revue Musicale, numéro spécial Varèse - Xenakis - Berio - Pierre Henry , Paris 1968, pp. 85-93.

- Enzo Restagno (ed.), Berio , Torino, Edizioni EDT 1995, ISBN 88-7063-248-2 .

- Edoardo Sanguineti, Teatro. K, Passaggio, Interpretation of Dreams, Protocolli , Milano, Feltrinelli 1969.

- Edoardo Sanguineti, Per Musica , a cura di Luigi Pestalozza, Modena / Milano, Mucchi / Ricordi 1993.

- Charlotte Seither , dissociation as a process. "Sincronie for string quartet" by Luciano Berio , Kassel, Bärenreiter 2000, ISBN 3-7618-1466-6 .

- Peter Stacey, Contemporary Tendencies in the Relationship of Music and Text with Special Reference to "Pli selon pli" (Boulez) and "Laborinthus II" (Berio) , New York / London, Garland 1989.

- Ivanka Stoïanova, Verbe et son “center et absence”. On "Cummings is the poet" de Boulez, "O King" de Berio et "For voices ... Missa est" de Schnebel , in: Musique en jeu , 1/1974, pp. 79-102.

- Ivanka Stoïanova, Texte - geste - musique , Paris (10/18) 1978, (»O King«, pp. 168–173).

- Ivanka Stoïanova, Principles of Music Theater with Luciano Berio - “Passaggio”, “Laborintus II”, “Opera” , in: Otto Kolleritsch (ed.), Opera today. Forms of Reality in Contemporary Music Theater , "Studies on Valuation Research 16", Graz / Vienna, Universal Edition 1985, pp. 217-227.

- Ivanka Stoïanova, Luciano Berio. Chemins en musique , Paris, La Revue Musicale 1985, No. 375-377.

- Ivanka Stoïanova, Procédés narratifs dans le théâtre musical récent: L. Berio, S. Bussotti et K. Stockhausen , in: Ivanka Stoïanova, Entre Détermination et aventure. Essais sur la musique de la deuxième moitié du XXème siècle , Paris (L'Harmattan) 2004, pp. 243-276.

- Ulrich Tadday (ed.): Music Concepts. Luciano Berio , Munich, edition text + kritik 2005, 124 pages, ISBN 3-88377-784-6 .

- Marco Uvietta, "È l'ora della prova": un finale Puccini-Berio per "Turandot" , in: Studi musicali 31/2002, pp. 395-479; english translation: "È l'ora della prova": Berio's finale for Puccini's "Turandot" , in: Cambridge Opera Journal 16/2004, pp. 187-238.

- Matthias Theodor Vogt, Listening as a Letter of Uriah: A note on Berio's "Un re in ascolto" (1984) on the occasion of the opera's first performance in London (February 9, 1989) , in: Cambridge Opera Journal 2/1990, pp . 173-185.

- Jean-François Lyotard , "'A Few Words to Sing' : sequence III ", in: Jean-François Lyotard, Miscellaneous Texts II: Contemporary Artists . Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2012, ISBN 978-90-586-7886-7

Web links

- Centro Studi Luciano Berio - Luciano Berio's Official Website , accessed July 15, 2014

- Luciano Berio at Universal Edition , accessed July 15, 2014

- Tempo Reale , founded by Luciano Berio in 1987 - Villa Strozzi, Florence (I), accessed July 15, 2014

- Literature by and about Luciano Berio in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Luciano Berio in the German Digital Library

- Literature on Luciano Berio in the bibliography of the music literature

- Obituaries

- “Just listen, always into the new” , Neue Musikzeitung , No. 7–8, 2003, pp. 33f., Accessed on July 15, 2014

- "Luciano Berio Is Dead at 77; Composer of Mind and Heart " , New York Times , May 28, 2003. Retrieved on 15 July 2014

Individual evidence

- ^ Honorary Members: Luciano Berio. American Academy of Arts and Letters, accessed March 6, 2019 .

- ↑ "Corrections" , New York Times , May 30, 2003. Retrieved on July 15, 2014

- ^ Hannes Fricke: Myth guitar: history, interpreters, great hours. Reclam, Stuttgart 2013, ISBN 978-3-15-020279-1 , p. 208.

- ↑ thefreelibrary.com: Placido Domingo Outlines His Plan for Los Angeles Opera

- ↑ Los Angeles Magazine June 2002 in Google Book Search

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Berio, Luciano |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Italian composer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | October 24, 1925 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Oneglia |

| DATE OF DEATH | May 27, 2003 |

| Place of death | Rome |