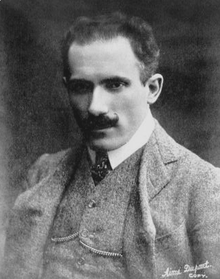

Arturo Toscanini

Arturo Toscanini (born March 25, 1867 in Parma , † January 16, 1957 in New York ) was an Italian conductor and is widely regarded as one of the most important orchestral conductors of his time.

life and work

Beginnings

After studying the cello , Toscanini decided in 1885 to become a conductor. He made his first experiences as a conductor in 1886 during a tour of Brazil. In 1895 he got a job in Turin . As a 29-year-old, he was allowed to conduct the world premiere of the opera La Bohème by Giacomo Puccini on February 1, 1896 because of his commitment to the work , although he was originally only intended to conduct the third position. In 1898 Toscanini went to La Scala in Milan , where he served as music director until 1903 .

Toscanini married Carla De Martini on June 21, 1897 when she was not yet 20 years old. The first child, Walter, was born on March 19, 1898. Daughter Wally was born on January 16, 1900. Giorgio followed in September 1901 but died on June 10, 1906 of diphtheria . In the same year the second daughter Wanda was born.

Probably during the premiere of the opera Zazà in 1900, he met the singer Rosina Storchio , who played the leading role here. Toscanini began an affair with Storchio, which resulted in a son, Giovannino. Giovannino was born with severe brain damage and died at the age of 16. For the 1905/1906 season Toscanini returned to the Teatro Regio in Turin and conducted, among other things, Madama Butterfly and the new opera Siberia by Umberto Giordano (this premiered, a year later he also conducted the premier in Buenos Aires ). From 1906 to 1908 he was again music director of the Teatro alla Scala in Milan.

The world career

In 1908 he moved to the Metropolitan Opera in New York, but returned to Europe a few years later. In addition to other orchestras, he also conducted many concerts with the Vienna Philharmonic - at the Vienna Musikverein and in Salzburg.

Shortly after the First World War , Toscanini was impressed by Benito Mussolini , whom he saw at a meeting in Milan in early 1919, when he was still using radical socialist rhetoric. In the parliamentary election in 1919 Toscanini ran on the list of Mussolini's Fasci di combattimento , which, however, remained completely insignificant and did not receive a single parliamentary seat. In the period that followed, however, he kept his distance from Mussolini and the fascists because he rejected the violence they exercised. As early as 1922, the year of the March on Rome , he rejected the request to have the party anthem Giovinezza played following a performance by Falstaff .

From 1921 to 1929 Toscanini officiated for the third time as musical director of La Scala in Milan. When the government ordered portraits of Mussolini and King Victor Emanuel III in 1925 . To hang it up in all public buildings, Toscanini refused to implement it in La Scala in Milan. He circumvented the order to play the Giovinezza on the national holiday of April 21st (“the birthday of Rome”) before concerts all over the country by not scheduling a performance, but only a rehearsal. Despite pressure and threats from the rulers, La Scala remained closed on April 21, 1926.

Mussolini announced that he would attend the world premiere of Puccini's Turandot, scheduled four days later , and demanded that the party anthem be played when he moved into the theater. Toscanini stayed tough, however, and the premiere took place without the Duce . Toscanini had the ending of Turandot , which was completed by Franco Alfano after Puccini's death, shortened. This abridged version is still played today , along with the full version and another version by the Italian composer Luciano Berio .

Toscanini's resignation from the post of music director at La Scala in 1929 was partly motivated by political pressure, but it also corresponded to his artistic interest in concentrating less on operas and more on a symphonic repertoire. He had been a guest conductor at the New York Philharmonic Orchestra since 1926, and was music director there from 1929 to 1936.

During his frequent engagements in Europe, his assistant, the German-American conductor Hans Lange , took over the rehearsals with the orchestra. During a stay in his Italian homeland in May 1931, Toscanini was attacked and beaten by young fascists in front of the Teatro Comunale in Bologna because he still refused to play Giovinezza .

1934 led Toscanini at the Vienna State Opera , the Requiem by Giuseppe Verdi and later two performances of Beethoven's Fidelio . That is why he brought his advice to the reconstruction of the Vienna State Opera after the Second World War and - for acoustic reasons - spoke out in favor of using wood as a building material in the auditorium. Toscanini shaped the Salzburg Festival for several years as a conductor . Until 1937 he directed important concerts and opera productions there, such as Verdi's Falstaff , Richard Wagner's Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg or Mozart's Die Zauberflöte .

emigration

Toscanini emigrated to the USA in 1937 because Italian fascism and German National Socialism were increasingly repulsing him. From then on, he led the NBC Symphony Orchestra, which was founded especially for him . As early as 1937 he made the first complete recording of Beethoven's nine symphonies with this orchestra. Toscanini canceled his appearances in Salzburg, planned for 1938, after the annexation of Austria to the National Socialist German Reich. In contrast, on December 26, 1936, he conducted the first concert of the newly founded Palestine Orchestra , which was renamed the Israel Symphony Orchestra from 1948.

By marrying his daughter Wanda with the piano virtuoso Vladimir Horowitz , Toscanini was able to present a legendary recording of Tchaikovsky's 1st Piano Concerto with his son-in-law. In a single benefit performance of the same work at Carnegie Hall in New York in 1943, the two artists managed to raise eleven million dollars from the audience - for war bonds that were issued instead of tickets.

In 1946 Toscanini produced a complete recording of the opera La Bohème for New York Radio on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the premiere he directed at the time. This is still considered the most accurate recording in the professional world. He discovered the soprano Renata Tebaldi and brought her to the rebuilt La Scala in Milan , where Toscanini conducted the opening concert in 1946. In 1947 Toscanini brought Hans Lange, who had become conductor of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in 1936 , to New York for a series of concerts with the NBC Symphony Orchestra. In addition, Toscanini invited the young Italian conductor Guido Cantelli to a series of concerts in New York in 1948/49 . He was enthusiastic about the young colleague whose career he promoted and who is considered to be Toscanini's musical heir. However, Cantelli died in a plane crash in 1956 - before his mentor. In order to spare Toscanini, who is almost 90 years old, this news was withheld from him.

After the war, Toscanini's interpretations of the works of Ludwig van Beethoven and Giuseppe Verdi were particularly famous . The recording of Toscanini's final performance of the Verdi Requiem on 27 January 1951 after finding a second band version as "Accidental Stereo" recording (one real , because recorded with two different microphones, but as such not originally planned stereo Recording) and first published in stereo in 2010.

The last concert

The recording of Toscanini's last concert, as well as that of the concert in March 1954 (with Tchaikovsky's “Pathetique” symphony as the focus of the program), is one of John “Jack” Pfeiffer's early stereo experimental recordings . Arturo Toscanini conducted this last public concert on April 4, 1954 at Carnegie Hall in New York. It became a famous performance due to Toscanini's blackout during the concert. He conducted his own symphony orchestra during the concert, which was broadcast live on NBC. The program included only works by Wagner , including the Lohengrin prelude and the scene on the Venusberg (Bacchanal) from Tannhauser . In the latter, the penultimate work of the concert, Toscanini's blackout happened, he stopped conducting for a minute and put a hand over his eyes. The orchestra stopped playing for a moment until the first cellist gave the entry; NBC's control room immediately faded out the performance and played a Brahms symphony from the tape. When Toscanini started conducting again, the transmitter faded back into the hall. Toscanini no longer accepted the final applause from the audience.

The incident is interpreted in the context that NBC Toscanini had previously given to understand that they wanted to dissolve the orchestra and that he would end his conducting career. A few months later, Toscanini's orchestra was actually dissolved and all musicians sacked. Toscanini never appeared again as a conductor.

Toscanini died on January 16, 1957 at his home in the Bronx, New York . His body was transferred to Italy and buried in the central cemetery in Milan .

Movies

- Toscanini about himself. TV documentary, France, 2008, 90 min., Director: Jean-Christophe Rose, production: arte France Summary

- Il giovane Toscanini (1988), Italian-French film by Franco Zeffirelli

literature

- Robert C. Marsh: Toscanini the master conductor. Pan-Verlag, Zurich 1958.

- Harvey Sachs: Toscanini: musician of conscience . Liveright Publishing Corporation, New York / London [2017], ISBN 978-1-63149-271-6

- You are a savage . In: Der Spiegel . No. 19 , 1951 ( online ).

- “A conductor, yes, that's me” . In: Der Spiegel . No. 31 , 1977 ( online ).

- "Give me, give me, more and more" . In: Der Spiegel . No. 31 , 2002 ( online ).

Web links

- Works by and about Arturo Toscanini in the catalog of the German National Library

- Newspaper article about Arturo Toscanini in the 20th century press kit of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

- Toscanini Online (English)

- Arturo Toscanini in the Internet Movie Database (English)

Individual evidence

- ^ A b c d Emily Freeman Brown: A Dictionary for the Modern Conductor. P. 344, entry Toscanini, Arturo .

- ^ Harvey Sachs: The Letters of Arturo Toscanini . P. 67

- ↑ Harvey Sachs: The Straight Path. In: Sachs: Arturo Toscanini from 1915 to 1946. Art in the Shadow of Politics. EDT. Musica, Turin 1987, pp. 1-20, at p. 5.

- ↑ Harvey Sachs: The Straight Path. In: Sachs: Arturo Toscanini from 1915 to 1946. Art in the Shadow of Politics. EDT. Musica, Turin 1987, pp. 1-20, at p. 6.

- ↑ Harvey Sachs: The Straight Path. In: Sachs: Arturo Toscanini from 1915 to 1946. Art in the Shadow of Politics. EDT. Musica, Turin 1987, pp. 1-20, at p. 9.

- ↑ Harvey Sachs: The Straight Path. In: Sachs: Arturo Toscanini from 1915 to 1946. Art in the Shadow of Politics. EDT. Musica, Turin 1987, pp. 1-20, at p. 11.

- ↑ Harvey Sachs: The Straight Path. In: Sachs: Arturo Toscanini from 1915 to 1946. Art in the Shadow of Politics. EDT. Musica, Turin 1987, pp. 1-20, at p. 12.

- ↑ Group photo 1926, Toscanini with artists from La Scala in Milan and the New York Metropolitan Opera in front of Giuseppe Verdi's birthplace. Retrieved June 6, 2020 .

- ^ Music: Lange's own . In: TIME Magazine , November 25, 1935

- ↑ Harvey Sachs: The Straight Path. In: Sachs: Arturo Toscanini from 1915 to 1946. Art in the Shadow of Politics. EDT. Musica, Turin 1987, pp. 1-20, at p. 14.

- ↑ Joseph Horowitz : Understanding Toscanini. A Social History of American Concert Life. University of California Press, Berkeley / Los Angeles 1994, pp. 375-376.

- ↑ Arturo Toscaninis conducts his last concert . Bayern Klassik, calendar sheet from April 4, 2012

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Toscanini, Arturo |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Italian conductor |

| DATE OF BIRTH | March 25, 1867 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Parma |

| DATE OF DEATH | January 16, 1957 |

| Place of death | New York City |