Madama Butterfly

| Work data | |

|---|---|

| Title: | Madama Butterfly |

Madama Butterfly , illustration by Adolfo Hohenstein |

|

| Shape: | “Tragedia giapponese” in two or three acts |

| Original language: | Italian |

| Music: | Giacomo Puccini |

| Libretto : | Giuseppe Giacosa and Luigi Illica |

| Literary source: |

John Luther Long : Madame Butterfly , David Belasco : Madame Butterfly |

| Premiere: | 1) February 17, 1904 2) May 28, 1904 |

| Place of premiere: | 1) Teatro alla Scala , Milan 2) Teatro Grande, Brescia |

| Playing time: | approx. 2 ½ hours |

| Place and time of the action: | A hill above Nagasaki , around 1900 |

| people | |

|

|

Madama Butterfly is an opera (original name: "Tragedia giapponese") by Giacomo Puccini . The libretto is by Giuseppe Giacosa and Luigi Illica . It is based on the story Madame Butterfly (1898) by John Luther Long and the tragedy Madame Butterfly. A Tragedy of Japan (1900) by David Belasco . The opera was premiered in its original version as a two-act play on February 17, 1904 at the Teatro alla Scala in Milan. The first female singer in the title role was the soprano Rosina Storchio , who was admired by Puccini . The first performance of the three-act new version took place on May 28, 1904 in Brescia .

action

The opera is set in Nagasaki around 1900.

The content removed in the second version is reproduced in smaller font.

first act

A Japanese house with a terrace and garden on a hill, in the background Nagasaki with the harbor

The American naval officer Pinkerton - stationed in Nagasaki - has acquired a house through the agent Goro for use for 999 years, including the geisha girl Cio-Cio- San , called Butterfly. Goro shows him around the house and introduces him to the employees, including the maid Suzuki. Pinkerton makes fun of their names and gives them numbers instead. Now the Consul Sharpless appears, and Pinkerton enthuses about his indulgent Yankee life (Pinkerton: "Dovunque al mondo"). He is happy to even be able to terminate his Japanese marriage on a monthly basis at any time. Sharpless advises him not to be too careless about the new relationship: Butterfly had asked about America at the consulate and was taking the marriage very seriously. But Pinkerton dismisses this idea. He drinks to his future marriage to a real American woman.

Goro announces the arrival of Butterfly and her friends. She tells Pinkerton and Sharpless their life story in a good mood: Since their once noble family became impoverished, she has worked as a geisha. Her father passed away and she is fifteen years old. Now the government commissioner, the registrar and Butterfly's relatives also arrive. During the introduction, Pinkerton meets Butterfly's uncle Yakusidé and a cousin with her son. The mother, the aunt and other relatives admire the beautiful house, while the cousin and other relatives make derogatory remarks about the planned wedding. Yakusidé is only interested in wine. Butterfly shows Pinkerton her personal belongings, including the dagger her father used to commit seppuku on the orders of Mikado , as well as some religious ancestral figures. She informs Pinkerton in secret that the day before she accepted the Christian faith in the mission house without the family's knowledge (Butterfly: “Io seguo il mio destino”). She casually mentions that Pinkerton paid 100 yen for her and throws the figures aside.

The commissioner now officially wed Pinkerton and Butterfly. There is a brief interruption when Yakusidé and the child reach for the candy prematurely. Sharpless and the commissioner say goodbye. The family toast the couple. Pinkerton asks Yakusidé, who is now drunk, to perform a song (Pinkerton: "All'ombra d'un Kekì"). The celebration is abruptly ended by Butterfly's uncle, a bigwig (priest): He curses Butterfly for her visit to the mission house. She is rejected by her indignant family. After the loved ones leave, Pinkerton comforts his bride. Suzuki says a Japanese evening prayer in the house. Pinkerton and Butterfly enjoy the silence of the evening that has now begun together for a while (Butterfly / Pinkerton: “Viene la sera”). Suzuki then prepares Butterfly for the wedding night. Both enjoy their love in the garden (duet: “Bimba dagli occhi pieni di malia”). Butterfly admits that she was shocked when she found out about his proposal. She is happy with the slightest affection (duet: “Vogliatemi bene, un bene piccolino”). When Pinkerton compares her to a trapped butterfly that is nailed down so that it cannot escape, she believes they are now united forever.

Second act [second act, first part]

The interior of Cio-Cio-San's house

Three years have passed. Pinkerton left Butterfly shortly after the wedding but promised to come back soon. Suzuki asks the Japanese gods that Butterfly may find happiness again. Butterfly rather hopes in the God of the Americans. Although Pinkerton ordered the consul to pay for their apartment, they are now facing financial problems. Butterfly reminds the doubting Suzuki of Pinkerton's promise to return when the roses bloom and the young robins chirp in the nest. She imagines his arrival in a white warship (Butterfly: “Un bel dì, vedremo”). Suzuki withdraws.

Goro and the consul arrive in the garden. Butterfly greets you happily. Sharpless has received a letter from Pinkerton. Before he can show it, Butterfly wants to know when the robins are breeding in America. Sharpless has no answer to that. With Goro's support, the rich Yamadori presents: he wants to marry Butterfly. An abandoned wife is considered divorced under Japanese law. She mocks him: her “American” marriage is not so easy to resolve. Yamadori says goodbye with a heavy heart. Sharpless now wants to carefully prepare Butterfly for Pinkerton to be on her way to Japan, but not to stay with her. He begins to read her the letter - but Butterfly prevents him from communicating the bitter message to her because she interrupts him after every line and interprets everything according to her wishes. Sharpless nevertheless advises her to accept Yamadori's proposal. Butterfly presented her three-year-old child, Pinkerton's son, about whom he knew nothing. Sharpless should tell Pinkerton about him, then he would hurry over. Turning to her son, she explains that she would rather die than beg or work as a geisha again (Butterfly: "Che tua madre"). His name is "Dolore" ("sorrow"), but when his father returns he will be called "Gioia" ("jubilation"). Sharpless promises to tell Pinkerton about his son and leaves. Suzuki forcibly pulls Goro into the apartment and accuses him of spreading false rumors about the child's father. Butterfly throws him out under threats. Suzuki carries the child away.

Suddenly a cannon shot heralds the arrival of Pinkerton's ship. Butterfly asks Suzuki to decorate the house with blossoming cherry branches and flowers for the reception (duet: “Scuoti quella fronda”). She has her wedding dress brought to her to wait for Pinkerton with Suzuki and her son. She sings a lullaby for the child. While Butterfly looks outside through small holes in the wall, Suzuki and the child soon fall asleep. Outside there are mysterious voices ( Voci misteriose a bocca chiusa - humming choir).

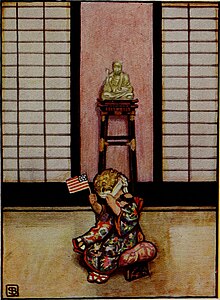

Third act [second act, second part]

Ibid

One night has passed awake, Pinkerton has not yet appeared. Butterfly withdraws with the child to find some rest. Suzuki promises to fetch her if Pinkerton shows up. Shortly afterwards, Suzuki is surprised by Sharpless and Pinkerton. Kate, Pinkerton's wife, is waiting in front of the house. You are coming to bring the child into a secure future - to America. Pinkerton asks Suzuki not to wake Butterfly yet because he wants to ask her for help with the delivery. He remorsefully thinks back to the past (Trio Sharpless / Suzuki / Pinkerton: “Io so che alle sue pene”). Since he cannot bear to see Butterfly again, he flees the house after giving Sharpless some money for her (Pinkerton: "Addio fiorito asil"). Suzuki promises Kate to persuade Butterfly to leave the child to her. When Butterfly sees the consul and Kate, who is still waiting outside, on her return, she realizes the truth. Kate asks for the child. Butterfly sends everyone away and explains that she only wants to hand the child over to Pinkerton personally. She rejects the money Sharpless offered her. She asks Suzuki to take care of the child and leave them alone. She sings a song about death. Then she lights a lamp in front of a shrine, kneels down, takes her father's dagger and reads the samurai motto written on it: "Die with honor, who can no longer live with honor." As she puts the knife to her throat , her son comes running in. She drops the dagger, hugs it and kisses it passionately (Butterfly: "Tu, tu piccolo iddio"), before she places it on a mat, gives him a small American flag and blindfolds his eyes. Then she steps behind a screen. You can hear the knife fall and she falls to the ground. Pinkerton calls her from outside. She drags herself to the child with the last of her strength. Pinkerton and Sharpless find her dying next to him.

layout

Instrumentation

The orchestral line-up for the opera includes the following instruments:

- Woodwinds : three flutes (3rd also piccolo ), two oboes , english horn , two clarinets , bass clarinet , two bassoons

- Brass : four horns , three trumpets , three trombones , bass trombone

- Timpani , percussion : bass drum , snare drum , cymbals , triangle , tam-tam , Japanese tam-tam, glockenspiel , Japanese glockenspiel (or vibraphone ), bells in es', f ', f sharp', g 'and a'

- harp

- Strings

- Incidental music behind the scene: bells in a 'and e' ', tubular bells , Japanese bells, bird whistle, tam-tam, big tam-tam, viola d'amore , cannon blow, noises from an anchor chain, humming choir (soprano, tenor)

music

Essential for the work is the contrast between the western and the Far Eastern lifestyle, which Puccini also expressed musically from the beginning. The opera begins with a fugue in which Puccini processes an exotic musical theme in a typical western way. Pinkerton's confession “Dovunque al mondo” already contains the two main western themes of the opera. This aria is framed by a quote from the naval anthem of the time (from 1931 the American national anthem “ The Star-Spangled Banner ”) in the wind section. After Pinkerton's duet with the consul Sharpless, the western coloring is replaced by a Japanese one when the matchmaker Goro arrives with the women.

Puccini tried hard to achieve a believable "Japanese coloring". He used various sources for inspiration: He attended a performance by the geisha- trained actress and dancer Kawakami Sadayakko during her world tour in March and April 1902. The wife of the Japanese ambassador in Rome, Hisako Oyama, sang traditional folk songs for him and helped him the Japanese name. He also received advice from the Belgian musicologist and Asia expert Gaston Knosp. He was able to fall back on European music collections of transcribed Japanese melodies and in January 1903 asked Alfred Michaelis of the Gramophone Company for records of Japanese folk music. The latter, however, may have arrived too late. An excerpt from the Japanese national anthem Kimi Ga Yo can be heard at the appearance of the Imperial Commissioner . Two motifs of the Cio-Cio-San can be traced back to Chinese folk music. It was not until 2012 that the musicologist W. Anthony Sheppard proved that Puccini took it from a music box made in Switzerland with western assimilated Chinese melodies. This instrument was a combination of a carillon and a harmonium called a "harmoniphône" . The first of these melodies is particularly closely related to the figure of Butterfly. In the original Chinese text, a man depicts a woman's whole body in an erotic way. In the opera, the melody appears for the first time in its entirety in the first act to the words “Io seguo il mio destino”, in which Cio-Cio-San Pinkerton describes what she has given up because of him. The mechanical sound of the music box, which naturally could not reproduce some peculiarities of Far Eastern music such as the typical glissandi or the original timbre of the instruments, also influenced Puccini's instrumentation of the Japanese-colored passages.

The result of Puccini's studies are extremely unusual timbres, which he achieved with instruments such as tam-tams, Japanese bell drums, Japanese keyboard glockenspiel or tubular bells. The comments of the Japanese relatives Cio-Cio-Sans at the wedding ceremony are played over a pentatonic ostinato . The setting of the accompanying voices also appears exotic in many ways. Puccini achieves this through methods that are otherwise untypical for him, such as instruments led in unison with the singing voice or empty fifths . He also uses organ points , bass ostinati, sound changes, whole tone sequences and excessive triads . Puccini mainly uses all these techniques for the secondary characters. Pinkerton's role, on the other hand, corresponds entirely to his typical lyrical idiom. American peculiarities are only certain English expressions or the quotation of the later American national anthem. The music of the Cio-Cio-San combines Far Eastern and European characteristics.

Richard Erkens pointed out that Puccini provided the title character with three different "dimensions". At the beginning she belongs to the Japanese “women”. While she climbs the hill with the other women, an original Japanese melody is hummed, the dance motif of the "rising sun" from the Kabuki theater, accompanied by bassoon and string pizzicati , whose sounds are reminiscent of the Japanese instruments koto and shamisen make you think. At the same time, Cio-Cio-San is oriented towards the west. The seductive Largo melody sung backstage is based entirely on Western harmony. The third aspect shows it as a connection between eastern and western elements. At the end of her scene she asks the other women to imitate her and to kneel in front of Pinkerton. This pantomime is accompanied by a pentatonic melody, the Chinese "Shiba mo" from the "Harmoniphône", which is accompanied by western instruments with western harmonies. The east kneels before the west not only in the scenery, but also in the music.

Important pieces of music

Vogliatemi bene, un bene piccolino

This love duet ends the first act. It is dominated by Butterfly's intimate singing. Pinkerton is actually not interested in a long-term relationship with Butterfly. Nevertheless, he feels drawn to her and he desires her. She thinks she has made a good match with the marriage and wishes him to love her a little too.

Un bel dì, vedremo

The aria is the musical climax of the second act. Butterfly has been waiting for her husband to return for three years. She is impoverished and socially despised. She is divorced because her husband rejected her, but she holds on to her belief that he will come back. In the aria she imagines how he will come back and how she will then triumph.

Addio fiorito asil

This is Pinkerton's only aria. After returning to Cio-Cio-San's house and speaking to Suzuki about how it would be too painful for Cio-Cio-San to say goodbye to her personally, he conjures up the happy hours together and confesses his cowardice.

Do, do piccolo iddio

This is the opera's death and final aria. Butterfly kneels to kill herself with her father's knife. Suddenly your child comes in. She says goodbye. The child leaves the scene and Butterfly kills herself. Then the music becomes dramatic again. Pinkerton calls out "Butterfly" three times. The orchestra has the last word and initially seems to traditionally close in the tonic (here in B minor ), before surprisingly adding the sixth chord to the submediate ( G major ) (by the individual psychologist and suicide researcher Erwin Ringel with regard to the open character interpreted this end of the opera with Butterfly's fantasy beyond his own death).

Work history

Emergence

The libretto for Madama Butterfly comes as the lyrics to Puccini's previous operas La Bohème and Tosca by Giuseppe Giacosa and Luigi Illica . All three operas were created under the “supervision” of the publisher Giulio Ricordi . The text is based on the story Madame Butterfly (1898) by John Luther Long and the one-act tragedy Madame Butterfly developed from it . A Tragedy of Japan (1900) by David Belasco .

Puccini's first contact with the material was a visit to the Duke of York's Theater in London on June 21, 1900, where David Belasco's one-act tragedy Madame Butterfly was played. Although he probably could not fully understand the English text, he kept the subject in mind from then on as a possible operatic subject. At first he was fascinated by the contrast between the American and Japanese milieu. His publisher Ricordi or his representative George Maxwell was soon able to obtain the rights from Belasco. In March 1901 Puccini received a translation of John Luther Long's on the drama-based story Madame Butterfly , 1898 in Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine was issued.

Based on Long's narrative, Luigi Illica immediately began drafting a libretto in which he provided several different settings in order to highlight the contrast between American and Japanese culture. For the Japanese local color, he was inspired by Pierre Loti's novella Madame Chrysanthème (1887). The work was originally conceived as a two-act play. Analogous to the beginning of La Bohème , where the main couple get to know each other, the first part is about the wedding of Cio-Cio-Sans with the American naval lieutenant to the subsequent love duet. The second part should consist of three scenes linked by narrative symphonic interludes. The two frame scenes were supposed to take place in the Cio-Cio-Sans house, while the middle section was to take place in the American consulate in Nagasaki. After Pinkerton's return, he was supposed to have a longer dialogue with the consul. In addition, an unexpected meeting between Cio-Cio-Sans and Pinkerton's new wife was planned. The play Belasco did not consider Illica until May / June 1901. Unlike Puccini, he and Giacosa, who was responsible for the verse, considered it less effective on the stage than Long's story. By the end of 1901 the libretto was well advanced. At this time, Puccini had already started composing the first act and was correspondence with Illica about the music of the second part.

In June 1902, work on the libretto was completed, and on September 7, Puccini completed the “piano course sketch” of the first act. During the following composition of the second act, he decided to make major changes to the sequence of scenes. The consulate scene was dropped, and the whole act should now be based directly on Belasco's play. The objections of the librettists were in vain. In the new structure, the change of location was no longer necessary, and the characters Pinkertons and his wife only appeared one-dimensional. Instead, the dramatic focus is on the emotional life of the heroine. In addition, Puccini was able to transfer the image he admired of the "wistful night" from Belasco's play into his opera. After a car accident on February 25, 1903, Puccini had to interrupt work for several months. On September 15, the first act was completed, and on December 27, 1903 he was able to complete the composition. By this time, the premiere rehearsals may have already started. The orchestra sheet music was only available at the end of January 1904. Puccini was present at the rehearsals. Otherwise the audience was largely excluded.

premiere

The first two-act version of the opera premiered on February 17, 1904 at the Teatro alla Scala . The costumes were by Giuseppe Palanti and the set by Vittorio Rota and Carlo Songa (or according to Piper's Encyclopedia of Music Theater by Lucien Jusseaume). The soprano Rosina Storchio sang the title role. Other singers were Giuseppina Giaconia (Suzuki), Giovanni Zenatello (B. F. Pinkerton), Giuseppe De Luca (Sharpless), Gaetano Pini-Corsi (Goro), Paolo Wulmann (Bonze) and Emilio Venturini (Imperial Commissioner). Cleofonte Campanini was the musical director .

The premiere was a fiasco that Puccini never experienced before. He withdrew the score that same day. The planned Roman premiere was canceled. As reasons for the failure, apart from criticism of certain aspects of the work, the current anti-Japanese mood after the Russian-Japanese war that broke out on February 8 and disruptions from supporters of the competing publishing houses Ricordi and Sonzogno are cited as reasons for the failure .

Further versions

Puccini began revising the work immediately after the premiere. He made some cuts and minor changes. The main change was the division of the second act, which was felt to be too long, between the humming choir and the intermezzo sinfonico. The character of Pinkerton had strong characteristics of the "ugly American" in the first version and also contained comical elements. Puccini defused this in the later versions. For example, he deleted some condescending remarks by Pinkerton about the Japanese. In addition, Pinkerton received a new aria in the last scene ("Addio fiorito asil") in which he shows remorse for his behavior. In the first act, scenes with the drunk Yakusidé and the parasitic relatives of Butterfly were deleted, and in the second act a place in which Consul Sharpless offers Butterfly on behalf of Pinkerton's money. In the third act, Pinkerton now demands the child instead of his wife. Puccini also made some minor changes to the music. So he swapped the second and third notes in Butterfly's main theme and enlarged her vocal range in “O a me sceso dal trone” in the third act.

The second version was completed on March 24th and premiered on May 28th, 1904 in Brescia. The musical direction was again Cleofonte Campanini. Giovanni Zenatello (Pinkerton) and Gaetano Pini-Corsi (Goro), who had already sung in Milan, also took part here. Other performers included Salomea Krusceniski (Butterfly), Giovanna Lucacevska (Suzuki) and Virgilio Bellatti (Sharpless). The performance was a great success, which founded the subsequent international triumph of the opera.

In the next few years, Puccini revised the work several times - whenever he was able to take part in performance rehearsals. The versions for the Opéra-Comique in Paris (December 28, 1906), for the Metropolitan Opera New York (February 11, 1907) and for the Teatro Carcano in Milan (December 9, 1920) should be mentioned here. The editions printed in these years also differ from the respective performance material, so that the history of the various versions can no longer be fully traced in detail. In some piano reductions the name “BF Pinkerton” was changed to “Sir Francis Blummy” in order to avoid possible associations with the English expression “bloody fool” (“b. F.”) Or the German word “pee”. Puccini worked on the work again and again almost until his death. A definitive final version cannot be proven. For a long time a score based on the Paris version of 1906, which appeared in print in mid-1907 and also contains some of the New York changes, was considered "canonical" for a long time.

reception

The opera has been performed countless times since then. Piper's Encyclopedia of Musical Theater highlights the following productions:

- 1904: Buenos Aires - conductor: Arturo Toscanini ; with Rosina Storchio (Cio-Cio-San)

- 1905: Royal Opera House Covent Garden, London - Conductor: Cleofonte Campanini; with Emmy Destinn (Cio-Cio-San), Enrico Caruso (Pinkerton), Antonio Scotti (Sharpless)

- 1906: Opéra-Comique Paris - French premiere; Conductor: Franz Ruhlmann; with Marguerite Carré (Cio-Cio-San), Edmond Clément (Pinkerton) and Jean Périer (Sharpless)

- 1907: Metropolitan Opera New York - many performances under Toscanini; with Emmy Destinn or Geraldine Farrar (Cio-Cio-San) as well as Enrico Caruso (Pinkerton) and Antonio Scotti (Sharpless)

- 1925: Metropolitan Opera New York - director: Wilhelm Wymetals , stage: Joseph Urban ; Conductor: Roberto Moranzoni; with Florence Easton (Cio-Cio-San), Giovanni Martinelli (Pinkerton) and Antonio Scotti (Sharpless) - this production was performed almost annually until 1956

- 1925: Teatro alla Scala Milan - first new production at this house; Conductor: Toscanini; with Rosetta Pampanini (Cio-Cio-San) and Bruna Castagna (Suzuki) - Pampanini sang the role in many other houses in the following years

- 1930: London - Conductor: John Barbirolli ; with Margaret Sheridan (Cio-Cio-San)

- 1931: Krolloper Berlin - Conductor: Alexander von Zemlinsky ; with Jarmila Novotná , Charles Kullman and Mathieu Ahlersmeyer ; Director: Hans Curjel ; constructivist sets by László Moholy-Nagy

- 1935: Milan - Conductor: Victor de Sabata ; with Bice Adami (Cio-Cio-San)

- 1940: New York - Conductor: Gennaro Papi; with Licia Albanese (Cio-Cio-San)

- 1950: London - Conductor: Warwick Braithwaite, Directed by Robert Helpmann ; with Elisabeth Schwarzkopf (Cio-Cio-San) and Monica Sinclair (Suzuki)

- 1951: Milan - Conductor: Victor de Sabata; with Licia Albanese (Cio-Cio-San) and Giacinto Prandelli (Pinkerton)

- 1955: Chicago - Conductor: Nicola Rescigno ; with Maria Callas (Cio-Cio-San) and Giuseppe Di Stefano (Pinkerton)

- 1958: Metropolitan Opera New York - Conductor: Dimitri Mitropoulos , Director: Joschio Aojama; with Antonietta Stella (Cio-Cio-San), Eugenio Fernandi (Pinkerton) and Mario Zanasi (Sharpless) - this production was played until the 1980s

- 1978: Teatro alla Scala Milan - production: Jorge Lavelli ; Stage: Max Bignens ; Conductor: Georges Prêtre ; with Elena Mauti Nunziata (Cio-Cio-San) - Mannerist staging with elements of Kabuki theater; in the same year at the Paris Opera with Teresa Żylis-Gara (Cio-Cio-San).

- 1978: Komische Oper Berlin - production: Joachim Herz ; Conductor: Mark Elder - German translation by Joachim Herz and Klaus Schlegel; with parts of the first version; the production placed an emphasis on the criticism of colonialism

- 1982: Teatro La Fenice Venice - Director: Giorgio Marini; Conductor: Eliahu Inbal ; with Eugenia Moldoveanu and Mietta Sighele (Cio-Cio-San) - both the reconstructed first version and the fourth version were played here

- 1982: Chicago - Director: Harold Prince ; Conductor: Miguel Ángel Gómez Martínez , stage: Clarke Dunham, costumes: Florence Klotz , lighting director: Ken Billington ; with Elena Mauti Nunziata (Cio-Cio-San) - production in Kabuki style; Revived in 1986 with Anna Tomowa-Sintow in the title role

- 1983: Verona Arena - production: Giulio Chazalette; Conductor: Maurizio Arena; with Rajna Kabaiwanska and Jassuko Hajaschi - staging in "aestheticizing traditionalism"

- 1983: Charleston and Spoleto - Director: Ken Russell

- 1987: Glasgow - Director: Nuria Espert ; Conductor: Alexander Gibson; with Joko Watanabe (Cio-Cio-San) - here the action took place in Japan after the Second World War; the production was also played in London in 1988

- 1993: Opéra Bastille Paris - Director: Robert Wilson ; Conductor: Myung-Whun Chung ; with Diana Soviero (Cio-Cio-San) - "abstract light and movement direction"

Recordings

Madama Butterfly has appeared many times on phonograms. Operadis lists 136 recordings in the period from 1909 to 2008. Therefore, only those recordings that have been particularly distinguished in specialist magazines, opera guides or the like or that are worth mentioning for other reasons are listed below.

- 1909 (earliest known recording, excerpts, English): René Vivienne (Cio-Cio-San), Harriet Behnne (Suzuki), Vernon Stiles (B. F. Pinkerton), Thomas Richards (Sharpless). Columbia # 30152-63 (6x78s).

- August 1955 ( Opernwelt CD tip: “artistically valuable”): Herbert von Karajan (conductor), orchestra and choir of the Teatro alla Scala Milan. Maria Callas (Cio-Cio-San), Lucia Danieli (Suzuki), Luisa Villa (Kate Pinkerton), Nicolai Gedda (B. F. Pinkerton), Mario Borriello (Sharpless), Renato Ercolani (Goro), Mario Carlin (Yamadori), Plinio Clabassi (Bonze). EMI CD: 7 64421 2, EMI CD: CDS 7 47959 8, EMI LP: 29 1265 3 mono, Naxos historical 8.111026-27 (2 CD), Cantus Classics 500840 (2 CD).

- 1959 ( Grammy Award 1962 : “Best opera recording”; Opernwelt CD tip: “artistically valuable”): Gabriele Santini (conductor), orchestra and choir of the Teatro dell'Opera di Roma . Victoria de los Ángeles (Cio-Cio-San), Miriam Pirazzini (Suzuki), Silvia Bertona (Kate Pinkerton), Jussi Björling (B. F. Pinkerton), Mario Sereni (Sharpless), Piero de Palma (Goro), Arturo La Porta (Yamadori ), Paolo Montarsolo (bonze), Vera Magrini (mother). EMI CD: 4 83482 2, EMI LP: 41 4446 3.

- July 1962 ( Grammy Award 1964 : “Best opera recording”; Opernwelt CD tip: “artistically valuable”): Erich Leinsdorf (conductor), orchestra and choir of the RCA Italiana. Leontyne Price (Cio-Cio-San), Rosalind Elias (Suzuki), Anna di Stasio (Kate Pinkerton), Richard Tucker (B. F. Pinkerton), Philip Maero (Sharpless), Piero de Palma (Goro), Robert Kerns (Yamadori), Virgilio Carbonari (bonze), Fernanda Cadoni (mother). RCA Victor CD: 9026688842, RCA CD: RD 86160, RCA LP: VLS 45141 (3 LP), Sony BMG 82876 82622 2 (2 CD).

- August 1966 ( Opernwelt CD tip: “Reference recording”): John Barbirolli (conductor), orchestra and choir of the Teatro dell'Opera di Roma . Renata Scotto (Cio-Cio-San), Anna di Stasio (Suzuki), Silvana Padoan (Kate Pinkerton), Carlo Bergonzi (B. F. Pinkerton), Rolando Panerai (Sharpless), Piero de Palma (Goro), Giuseppe Morresi (Yamadori), Paolo Montarsolo (fat cat). EMI CD: 7 69654 2, EMI LP: 29 0839 3, EMI MC.

- April 1987 ( Opernwelt CD tip: “DDD recording”): Giuseppe Sinopoli (conductor), Philharmonia Orchestra London, Ambrosian Opera Chorus . Mirella Freni (Cio-Cio-San), Teresa Berganza (Suzuki), Marianne Rørholm (Kate Pinkerton), Josep Carreras (B. F. Pinkerton), Joan Pons (Sharpless), Anthony Laciura (Goro), Mark Curtis (Yamadori), Kurt Rydl (Bonze), Hitomi Katagiri (mother). DGG CD: 423 567-2 (3 CD).

literature

- Folker Reichert : Love was not involved. Who was Madame Butterfly? In: Damals 2009/9, pp. 58–63.

Web links

- Madama Butterfly : Sheet music and audio files in the International Music Score Library Project

- Piano reduction in the Indiana University Bloomington digital library

- The various versions of the libretto (Italian) as full text on the Stanford University opera server

- Work information and libretto of the first version (Italian) as full text on librettidopera.it

- Madama Butterfly (Giacomo Puccini) in the Corago information system of the University of Bologna

- Plot and libretto of it at Opera Guide landing page for URL upgrade currently unavailable

- Action with photos (productions of the Berlin State Opera in 1991 and the Zurich Opera in 2009)

Remarks

- ↑ modern transcription: Chōchō-san (Japanese for "woman butterfly")

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f Norbert Christen: Madama Butterfly. In: Piper's Encyclopedia of Musical Theater . Volume 5: Works. Piccinni - Spontini. Piper, Munich and Zurich 1994, ISBN 3-492-02415-7 , pp. 114-119.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Richard Erkens (ed.): Puccini manual. Metzler, Stuttgart 2017, ISBN 978-3-476-05441-8 (Metzler eBook).

- ^ W. Anthony Sheppard: Puccini and the Music Boxes. In: Journal of the Royal Musical Association, 140, 1 (Spring 2015), doi : 10.1080 / 02690403.2015.1008863 , pp. 41-92.

- ↑ Puccini's Music Box on YouTube , accessed May 24, 2018.

- ↑ Erwin Ringel: Unconscious - highest pleasure, opera as a mirror of life. Kremayr & Scheriau 1990, p. 190.

- ↑ February 17, 1904: "Madama Butterfly". In: L'Almanacco di Gherardo Casaglia ..

- ↑ May 28, 1904: "Madama Butterfly". In: L'Almanacco di Gherardo Casaglia ..

- ^ Discography on Madama Butterfly at Operadis.

- ↑ a b c d e f Giacomo Puccini. In: Andreas Ommer: Directory of all opera complete recordings. Zeno.org , volume 20.

- ↑ a b c d e Madama Butterfly. In: Harenberg opera guide. 4th edition. Meyers Lexikonverlag, 2003, ISBN 3-411-76107-5 , p. 696.