Enrico Caruso

Enrico Caruso (born February 25, 1873 in Naples ; † August 2, 1921 there ; actually Errico Caruso ) was an Italian opera singer . He is considered the most famous tenor at the beginning of the 20th century and one of the most important figures in the opera world .

Life

Caruso came from a poor family with many children who lived at 7 Via Santi Giovanni e Paolo in the Neapolitan district of San Carlo all'Arena . He was the third of seven children. The myth of his parents' 18 children is clearly refuted. His mother, whom he loved dearly, enabled him to go to school. As a child he sang in the Knabenalt church choir , and the priest immediately noticed his voice. Enrico then studied singing privately with local teachers, from the age of sixteen with the renowned teacher Guglielmo Vergine . Vergine was reportedly not convinced of Caruso's great career, but eventually tutored him for free, but on a contract that secured him 25% of all income in the first five years of a possible career. Caruso later took legal action against this and a settlement was reached. It was also Vergine who brought Caruso to change his first name from Errico to Enrico because of the better sound. Another teacher was Vincenzo Lombardi.

Caruso had his first engagement in his hometown of Naples, to which he remained connected throughout his life through an ambivalent love, as, in his opinion, he was not given the necessary recognition there: In the four years after his debut (at the age of nineteen) he stayed his career ignored. Caruso's unstoppable rise only began with the role of Loris at the premiere of Umberto Giordano's opera Fedora . He came back to Naples (already as a star), where the high society in the Teatro San Carlo still regarded him as a street boy singing under the balconies. He never forgot that and vowed never to sing in Naples again, but only to come back to eat spaghetti. He kept this oath all his life. The final international breakthrough he experienced in 1903 at the Metropolitan Opera in New York City in Rigoletto by Giuseppe Verdi , in which he sang the Duke. Rarely in a debut: He had to repeat an aria, “ La donna è mobile ”.

His private life caused a stir. He lived eight years unmarried with the opera singer Ada Giachetti , with whom he had two sons, Rodolfo and Enrico. The children are said to have been named after the main characters of the opera La Bohème , in which the parents met. For this reason, Enrico was nicknamed Mimi. Ada left the often unfaithful Caruso. She fled with his chauffeur, which led to a scandal and many lawsuits.

Caruso then lived for some time with Ada's sister Rina, also a singer, until, to everyone's surprise, he suddenly married the American millionaire daughter Dorothy Park Benjamin . With her he had a daughter, Gloria, at the age of 45.

Because of his wealth, Caruso was a target of the " Black Hand ", an early offshoot of the Sicilian Mafia in the United States, and was lucky enough to escape a bomb attack in Cuba . Caruso's generosity was legendary. For example, in his most successful years at the Metropolitan Opera, he gave gifts to almost all employees for Christmas. His humor was also famous. Again and again he took jokes with his stage colleagues, for example sewing up the sleeve of a coat that a colleague in La Bohème had to put on during the performance, or pouring water into a discarded hat that someone had to put on during the performance.

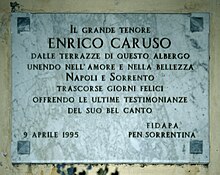

In the late autumn of 1920 Caruso contracted purulent pleurisy from a cold . Although he began to cough up blood and felt severe pain during a performance of L'elisir d'amore , the disease was not discovered in time. At first he refused to consult a doctor. He sang the last performances of La Juive by Halévy in December 1920, supported by his partner while standing, because otherwise he would not have been able to breathe. After a collapse at Christmas 1920, he underwent an operation and barely survived. He then returned to Italy for a vacation in the spring of 1921, where he first recovered at the Grand Hotel Excelsior Vittoria in Sorrento and was already planning performances at the Met Opera in New York City for the coming season. However, after a few months there was an unexpected relapse. He died shortly afterwards at the Grand Hotel Vesuvio in Naples at the age of 48, of pleurisy and blood poisoning, before he could go to Rome to see his doctors in the hospital.

Caruso's death was mourned in many parts of the world. Caruso was laid out in the royal church of San Francesco di Paola in Naples and accompanied in a large funeral procession to the Cimitero "Santa Maria del Pianto". King Victor Emmanuel III even opened the church, in which previously only royal weddings, baptisms and funerals had taken place, for Caruso. At the funeral on August 19, 1921, around a hundred thousand people lined Caruso's last path. Friends, companions and crowned heads from all over the world were present. The building facades along the funeral procession were covered with black sheets; shops in Naples remained closed. Since then, the singer's remains have been resting in a magnificent mausoleum behind marble, where countless admirers visit him to this day. From 1921 to 1930 Enrico Caruso was laid out in a glass coffin and his embalmed corpse could be viewed publicly - the coffin was only closed at the insistence of his wife.

Historical profile

Caruso's breakthrough came at the age of 24 with the role of Federico in the world premiere of Cilea's opera L'Arlesiana at the Teatro Lirico in Milan. He also took part in the world premieres of Fedora and La fanciulla del West . His most famous roles were Canio in Leoncavallos Pagliacci and Radames in Aida . Caruso, whose repertoire comprised 67 parts, sang in Milan , Naples , London and especially New York City . In New York City he was a permanent member of the Metropolitan Opera ensemble for a total of 18 seasons , all of which he opened .

Caruso was famous for his baritone vocal sound and his stage presence. In a performance of La Bohème he sang the aria vecchia zimmarra for the suddenly voiceless bass so convincingly that no one in the audience noticed it and he later even recorded the aria. His singing formant was determined to be 2800 Hz. His partner Geraldine Farrar reports how she stood on stage with Caruso for the first time and forgot to sing because she burst into tears at the beauty of his singing. Lina Cavalieri fell around his neck on the stage and kissed him so passionately out of enthusiasm that this kiss went down in history as the first "real" stage kiss. The name Carusos has become so famous and legendary that a singer is often compared to Caruso. Other great singers came and went and some have been remembered, but Caruso is the name everyone knows. Those who have seen him describe the onset of his voice with the warm power of an organ.

Caruso was initially a representative of the old Italian Belcanto school , but because of the drama of verismo he established a new, exemplary style of singing in which the focus was not on the beautiful presentation, but on becoming one with the character shown. During his guest performances Caruso was showered with honors, in Berlin 30,000 people gathered in front of the opera to see Caruso for a minute. Caruso was a big earner in the opera scene and the first to fill bullring with his singing (in November 1919 in Mexico City in front of 25,000 people). Caruso also holds the record of 863 appearances on the stage of the Metropolitan Opera (see also Metropolitan database ) within 17 years (between November 1903 and December 1920). So Caruso sang more performances at the Met than at any other opera house worldwide.

Numerous biographies of Caruso were written. The gramophone gained notoriety through its early recordings . Caruso had a close artistic friendship with Paolo Tosti and Giacomo Puccini , who wrote many of their works for him. He saw the Irish tenor John McCormack as his greatest competitor, but he valued him very much. Caruso was also active as a cartoonist and draftsman and created the melody (e.g. Dreams of Long Ago ) or the text (e.g. Campane a sera ) for some songs .

Recordings

Caruso recorded a total of 498 records , some of which, however, remained unpublished. These include not only opera arias, but also many popular songs from the repertoire of the “Canzone napoletana”, in particular “ O sole mio ” by Eduardo Di Capua , which he made world famous. It was Caruso who initiated the triumphant advance of the record through his work for the Victor Talking Machine Company . His Vesti la giubba (from Ruggero Leoncavallo's opera Pagliacci ), recorded for Victor on February 1, 1904 , is considered the first million seller in the record industry with over a million records sold since its release in May 1904 .

Since the playback speed of the disks was not exactly standardized at the time, it is important to play each disk at the correct speed; this was often not taken into account with older transfers (see also below on Caruso's aftermath in the film). A complete edition of Caruso's recordings was published by Naxos between 2000 and 2004. The recordings were played back at the correct tempos by Ward Marston, a recognized specialist in the restoration of historical sound recordings, and restored very carefully and in a balanced manner. An edition around ten years older, which includes most of Caruso's published recordings, is the 14-CD edition from Bayer Records , which has been processed with the NoNoise process and is thus severely distorted. In 1999 the Vienna Radio Symphony Orchestra backed the digitally carefully "modernized" recording of Caruso's voice with a modern orchestra, so that one can imagine what it would sound like if Caruso could make recordings today. The experiment called "Caruso 2000" is controversial among specialists and vocal connoisseurs.

In 2007, the Enrico Caruso Agency, together with the pianist Tommaso Farinetti, launched a new Caruso CD on which the young pianist Farinetti virtually encounters the immortalized Caruso and replaces the orchestral parts of the original recording with his piano accompaniment. In contrast to the older digital recordings, the recordings were made in a small concert hall and not artificially reverb. As a result, Caruso's voice is in the foreground, although the gap in sound quality between the old and the new recording cannot be completely overcome.

Filmography

Caruso took part in two silent films in 1918 , only one of which (My Cousin) is still a copy. The film was a success in Europe.

Caruso's aftermath

A fictional version of Caruso's life was made into a rather kitschy film in 1951 with Mario Lanza in the lead role under the title The Great Caruso . The film was banned in Italy because of its relatively fictitious content.

The film Fitzcarraldo (1982) by Werner Herzog with Klaus Kinski in the leading role of Fitzcarraldo starts with an appearance by Caruso in the Teatro Amazonas , the opera in Manaus (Brazil), where Caruso never actually sang. The soundtrack of the film consists for the most part of original recordings by Caruso, some of which were however transmitted at the wrong playback speed and therefore sound distorted.

Recordings of arias interpreted by Caruso make up the majority of the score for the film Match Point (2005) by Woody Allen .

The Italian singer and songwriter Lucio Dalla created a modern hymn to Caruso in 1986. His song, entitled Caruso , has been interpreted by numerous artists.

The asteroid (37573) Enricocaruso and the Mercury crater Caruso are named after him.

various

- According to his wife Dorothy, Caruso drank two or three US liq.qt. Mineral water, whereas he did without milk and tea. He didn't drink beer or highballs either , but sometimes a little wine and an Alexander . He smoked two packs of Egyptian cigarettes a day.

- Caruso owned an important collection of gold coins, which was auctioned posthumously on June 28, 1923 and the following days by the auction house C. & E. Canessa in Naples. The catalog has 104 pages with 1458 ticket numbers and 64 collotype plates.

- Medal issues with the portrait of Caruso:

- 1902 medal in gold (for Caruso), silver (five pieces), bronze (21 pieces), 52 mm. Medalist: Egidio Boninsegna

- 1973 silver medal, 39 mm, 100th anniversary of his birth. Medalist: TP.

- 1973 medal in gold (500), silver (2,000), bronze (5,000), 60 mm, same occasion. Medalist: Bino Bini

- 1973 as before, but 40 mm.

- 1973 medal in silver, 50 mm, same occasion. The reverse shows the Villa Bellosguardo. Medalist: Bruno Catarzi

- 1973 cast medal in bronze, 120 mm. Medalist: Bruno Catarzi

literature

- Paul Bruns / Maximilian Hörberg (arrangement / ed.): Carusos Technik . Maximilian Hörberg, Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-00-023411-8 (revised version of the Charlottenburg 1922 edition).

- A. Lancellotti: Le voci d'oro. Palombi, Rome 1942.

- Frank Thiess : The tenor of Trapani . Novella. Reclam, Leipzig 1942.

- Eugenio Gara: Caruso. Storia di un emigrante . Rizzoli, Milan 1947.

- Ferdinand Pfohl : From the golden days of the opera - Caruso in Hamburg . In: Hamburger Jahrbuch für Theater und Musik 1947–48 , JP Toth, Hamburg 1947, pp. 218–261.

- Kurt Reis: Caruso, triumph of a voice . German book distribution and publishing company, Munich 1955.

- V. Tortorelli: Enrico Caruso nel centenario della nascita . Artisti Associati, Rimini 1973.

- Franz Werfel : The siblings of Naples . Novel. S. Fischer, Frankfurt 1991 (original edition 1931).

- Christian Springer : Enrico Caruso. Tenor of modernity . Holzhausen, Vienna 2002, ISBN 3-85493-063-1 .

- Frank Thiess : Caruso in Naples . Bertelsmann Lesering 1955.

- Jean-Pierre Mouchon: Particularités physiques et phonétiques de la voix enregistrées de Caruso. Preface by Prof. André Appaix. Le Sud Médical et Chirurgical, 99e année, n ° 2509, Marseille October 31, 1964, 11.812-11.829.

- Jean-Pierre Mouchon: Enrico Caruso 1873-1921 Sa vie et sa voix. Étude psycho-physiologique, physique, phonétique et esthétique. Foreword by Dr. Édouard-Jean Guard. Imprimerie du Petit-Cloître, Langres 1966.

- Jean-Pierre Mouchon: Enrico Caruso. His Life and Voice. Editions Ophrys, Gap 1974.

- Jean-Pierre Mouchon: Enrico Caruso. L'homme et l'artiste. vol. I, II, III. Dissertation. Sorbonne, Paris 1978.

- Jean-Pierre Mouchon: Chronologie de la carrière artistique du ténor Enrico Caruso. Académie régionale de chant lyrique, Marseille 1992.

- Riccardo Vaccaro: Caruso. Foreword by Ruffo Titta Jr. Edizioni Scientifiche Italiane, Naples 1995.

- Jean-Pierre Mouchon: Enrico Caruso. L'homme et l'artiste. vol. I & II. Terra Beata, Marseille 2011 (book and CD-Rom).

- Jean-Pierre Mouchon, Enrico Caruso. Deuxième partie. (La voix et l'art, les enregistrements). Étude physique, phonétique, linguistique et esthétique. Volume III. Association Internationale de chant lyrique TITTA RUFFO, Marseille 2012.

- Michael Jahn : Caruso and Ruffo in “Rigoletto” (1906). In: Verdi and Wagner in Vienna 4 . Verlag Der Apfel, Vienna 2015, pp. 43–62, ISBN 978-3-85450-325-5 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Enrico Caruso in the catalog of the German National Library

- Newspaper article about Enrico Caruso in the press kit of the 20th century of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

- The time: Caruso's first name - Enrico or Errico

- “Rigoletto”: Bella figlia dell 'amore by Giuseppe Verdi . Recording with Enrico Caruso, Marcella Sembrich , Antonio Scotti and Barbara Severina

Individual evidence

- ↑ Patricia Schultz: 1,000 Places to See Before You Die. Workman Publishing Company, New York City 2010, ISBN 978-0-7611-6102-8 , p. 188.

- ^ Deutsche Oper Berlin: Concerts from "L'Arlesiana to Jazz" in February 2018. In: Das Opernmagazin . Detlef Obens, February 11, 2018, accessed on February 22, 2018 .

- ^ Pierre Van Rensselaer Key, Bruno Zirato: Enrico Caruso. A biography. Little, Brown, and Company, Boston 1922, pp. 396 f. ( Archive.org ).

- ↑ Katharina Eickhoff: SWR2 music lesson with Katharina Eickhoff. Heroes in tights - A short story of the tenors. In: swr.de. SWR2 , October 26, 2012, accessed on July 10, 2020, p. 7 (PDF; 251 kB).

- ^ Pietro Gargano / Gianni Cesarini: Caruso. Eine Biographie, Zurich 1991, p. 149.

- ↑ Dorothy Caruso: Enrico Caruso. His Life and Death. Simon and Schuster, New York City 1945, p. 157.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Caruso, Enrico |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Caruso, Errico (real name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Italian opera singer (tenor) |

| BIRTH DATE | February 25, 1873 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Naples |

| DATE OF DEATH | August 2, 1921 |

| PLACE OF DEATH | Naples |