Lucio Dalla

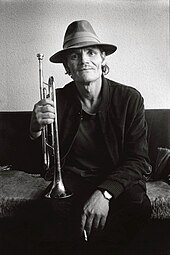

Lucio Dalla (born March 4, 1943 in Bologna , † March 1, 2012 in Montreux ) was an Italian musician, cantautore and actor .

The original jazz musician was one of the most important and innovative Italian cantautori. Always on the lookout for new influences, he explored various musical genres and worked with a large number of well-known national and international artists. As a songwriter, he initially limited himself to the composition, but soon took over the lyric poetry and wrote his own lyrics. In his more than 50-year career, Dalla played the piano , saxophone and clarinet , learning the latter two as a child.

His career went through several phases: from beat music to rhythmic and musical experimentation to canzone d'autore and to the limits of opera . He also achieved greater notoriety outside of Italy, and several of his songs were translated into other languages and published abroad.

biography

childhood

Lucio Dalla was born in Bologna in 1943 to Giuseppe Dalla (1896-1950), head of a sports club, and milliner Jole Melotti (1901-1976), and grew up in the city. As early as 1950, the father died of a tumor and the mother enrolled Lucio at the Collegio Vescovile Pio X in Treviso , where he went through elementary school and already appeared in school plays.

Also inspired by his uncle Ariodante Dalla , who was a successful singer in the 1940s and 1950s, Lucio started playing the accordion at a very young age. His mother recognized his talent early on and gave him a lot of freedom. When he was 15 he went to Rome. After completing compulsory school, he tried his hand at accounting, classical lyceum and language high school. At the same time, he has appeared on various occasions as a musician.

Youth and interest in jazz

Back in Bologna, Dalla developed a great interest in jazz. For his tenth birthday he had already received a clarinet as a present. He learned the instrument himself and performed with other amateur musicians in the city. Soon he became a clarinetist in the jazz formation Rheno Dixieland Band , where Pupi Avati played for a short time . The meeting with the American trumpeter Chet Baker , who was living in Bologna at the time, was significant ; the young Dalla was given the opportunity to perform with the jazz musician several times. He was very critical of pop music at this age. As a jazz musician, he later performed with Bud Powell , Charles Mingus and Eric Dolphy .

Dalla was on vacation in Manfredonia ( Apulia ) on his first trip to the south of the country , and his mother also received a house on the Tremiti Islands as a gift. The musician remained very attached to the area and especially to Manfredonia throughout his life; he spent his future vacations on the Tremiti and later set up a recording studio there. He saw himself shaped by the two contrasting ways of life of the north and south and also based his religiosity on the experiences of the south.

The 1960s

Debut with the Flippers

In 1960 Dalla took part with the Rheno Dixieland Band at the first European jazz festival in Antibes , where the group landed in first place. At that time he began to write his first own titles, including Il prode invertito and Avevo un cane… adesso non ce l'ho più . A professional group, the Second Roman New Orleans Jazz Band , consisting of Maurizio Majorana, Mario Cantini, Peppino De Luca, Roberto Podio and Piero Saraceni, became aware of Dalla. With this he recorded a song for the first time in a recording studio in 1961, as a clarinetist in the title Telstar , which was released as a single by RCA.

At the end of 1962 he joined the Flippers , a jazz formation made up of Franco Bracardi (piano), Massimo Catalano (trumpet), Romolo Forlai (vibraphone and percussion) and Fabrizio Zampa (drums), in which Dalla played the saxophone in addition to the clarinet and sang. Later he also played several times with Edoardo Vianello , whom the pinball machines often accompanied. With the Flippers, Dalla also received his first record deal. During some performances in Turin , he encountered the resentment of the local owners, as he often performed barefoot. Financially he was very limited at the time.

As a singer, he gradually received attention, especially for his scat singing, which would become one of his hallmarks. He was heard for the first time on the Flippers album At Full Tilt , in the song Hey You . A great admirer of James Brown , he used very rough and inharmonious vocals, with sudden changes in tone at the limits of musical logic. Thereby he established a trademark which also brought him the attention of Gino Paoli , who saw him as the first soul singer in Italy.

At the Cantagiro singing competition in 1963, the Flippers took part together with Edoardo Vianello and the song I Watussi . Gino Paoli, who also took part, managed to convince Lucio Dalla to embark on a solo career and leave the flippers .

Solo career: Cantagiro and Sanremo

In 1964, at the age of 21, Dalla recorded his first single as a soloist, with the songs Lei (non è per me) (text by Paoli and Sergio Bardotti) and Ma questa sera (text by Bardotti), which were performed by ARC, im Distribution of the RCA Italiana appeared, as well as his following singles and the debut album. His first solo experience at Cantagiro that year, where he presented lei (non è per me) , turned out to be a failure: the audience whistled at him and pelted him with tomatoes.

After this failure, in 1966 Dalla got a musical group from Bologna as a backing band, Gli Idoli , and recorded his first album with them, under the title in 1999 . It contained the following two songs, among others: Quand'ero soldato (awarded the Critics' Prize at the Festival delle Rose ) and Pafff… bum! . He presented the latter at the Sanremo Festival in 1966 , together with the Yardbirds . In 1967 he returned to Sanremo and sang Bisogna saper perdere , together with the Rokes of Shel Shapiro. 1967 was the year of suicide by Luigi Tenco , with whom Dalla had already worked and was friends.

After that he turned to beat music for a while . Songs from that phase were for example Lucio dove vai or especially Il cielo , with which he again won the critics' award at the Festival delle Rose. Here, too, he was noticed by his careless appearance. In general, Dalla was widely known for its spleens.

In 1968 he appeared as a narrator and singer in the episode film Franco, Ciccio e le vedove allegre by Marino Girolami, where he sang E dire che ti amo and Il cielo. With the song Fumetto he had a minor success in 1969, as it was used by the Rai as the theme song for the children's program Gli eroi di cartone . In 1970 he finally released the second album Terra di Gaibola , which, however, sold very poorly and was soon taken out of the trade by the RCA.

The 1970s

From 4/3/1943 to Piazza Grande

In 1971 he again took part in the Sanremo Festival, this time with the song 4/3/1943 (text by Paola Pallottino), and landed in third place. Initially titled as Gesù bambino ( Jesus child ), it had to be censored for the event; the new title was Dallas Birthdate, although the lyrics of the song (a young woman is expecting a child from an unknown Allied soldier) is not autobiographical. Other parts of the text also had to be censored. The song was Dallas by then the biggest sales success and reached number one on the charts. Dalida recorded the song in French (with a text by Pierre Delanoë ) and Chico Buarque successfully brought it to Brazil with Portuguese text.

In the same year the album Storie di casa mia was released , which, in addition to the hit single, contained a number of songs that increased Dallas' importance as a Cantautore. Musically, they are characterized by a simple and direct structure that, according to the folk model of Guccini and De André , is intended to convey only the lyrics. The arrangements are reserved and discreet and do not distract from the focus of the work, the narrative voice. The texts by Baldazzi, Bardotti and Pallottino deal with social issues that shape Dallas' new role: as an entertainer who is also thought-provoking. Among the titles included: Un uomo come me , La casa in riva al mare , Il gigante e la bambina (on pedophilia ), Per due innamorati or Itaca , a metaphorical dialogue between a sailor and his captain ( Odysseus ).

In 1972, Dalla also competed in Sanremo, this time with Piazza Grande , a song about a homeless person, with a text by Gianfranco Baldazzi and Sergio Bardotti and music by Dalla and Ron . Initially intended for Gianni Morandi , Dalla was allowed to present the contribution himself in the end. The eponymous square does not mean Piazza Maggiore in Bologna , as is often assumed , but Piazza Cavour, as Baldazzi made clear in 2011. Piazza Grande became one of Dallas' most famous songs along with 4/3/1943 . Although it became a classic of Italian music over time, it only reached eighth place in Sanremo.

The charity Amici di Piazza Grande onlus , active in Bologna since 1993, takes care of the care of needy homeless people, named after the song . The lyrics of the lyrics also found their way into the state final examination in 2001 , where they were used together with texts by Vincenzo Cardarelli , Umberto Saba and Sandro Penna for the topic of public spaces as a meeting place for memories. However , Dalla expressly refused to be classified as a poet .

The Roversi period

In 1973 Dalla ended his collaboration with the lyricists Sergio Bardotti and Gianfranco Baldazzi and stuck to the Bolognese poet Roberto Roversi. This three-year collaboration resulted in three albums that are considered fundamental to the creation of the canzone d'autore in Italy. The political content increased under Roversi. Dalla claimed to have learned innumerable things from the poet. The first album of this period was Il giorno aveva cinque teste from 1973. Both musically and lyrically it is difficult to interpret and very experimental. Then there was the idiosyncratic singing with frequent changes of registers and improvised jazz elements. The opening title Un'auto targata TO deals with immigration and property speculation; Songs like L'operaio Gerolamo and Alla fermata del tram , the instrumental track Pezzo zero and others like Il coyote , Passato presente and La canzone di Orlando follow .

The album Anidride solforosa was released in 1975 with a more traditional sense of form . This included Mela da scarto (on juvenile delinquency), Le parole incrociate (on crimes of the state after the unification), Carmen Colon (on reports of crimes and accidents) and the satirical La Borsa Valori (on activities on the stock exchange); also Tu parlavi una lingua meravigliosa and the theme song, which is dedicated to environmental protection. That year Dalla also took part in the socialist festival del proletariato giovanile . During this time, music and social engagement were closely linked and Dalla tried to appeal to an audience of workers and employees.

Finally, in 1976, Dalla and Roversi wrote and presented the play Il futuro dell'automobile e altre storie , which was broadcast by the Rai in early 1977. In the play, Dalla told a female chimpanzee the great deeds of Tazio Nuvolari , from which the next album Automobili emerged . Under pressure from the record company, Dalla assembled a selection of songs from the play on this album, which Roversi refused and led to the fact that he only had the songs registered under a pseudonym. For him, the red thread of the play was destroyed by the compilation in the album.

As a result of this disagreement, the collaboration between the two artists came to an end. Dalla wanted to open up more to the public, while Roversi insisted very rigorously on deepening the political content. Dalla felt the break was a trauma, but ultimately also as a starting point for writing her own texts. Songs that did not make it onto the album remained unpublished for a long time, including I muri del '21 , La signora di Bologna , Assemblaggio , Rodeo and Statale adriatica, chilometro 220 . Automobili is designed as a concept album . Especially because of the song Nuvolari , the album proved to be particularly successful and hit the charts for the first time. Other notable titles were Mille miglia , Il motore del 2000 and Due ragazzi, as well as Intervista con l'Avvocato , which deals with a fictional interview with Giovanni Agnelli .

The artistic maturity and the great success

In 1977 Dalla decided to retire to the Tremiti and work independently on his next album. His first own song lyrics were evidence of great maturity. The result of this work was the album Come è profondo il mare , in whose title song he processed metaphors about power and freedom of expression. Other songs were Quale allegria , Il cucciolo Alfredo , E non andar più via , Corso Buenos Aires and Disperato erotico stomp . Many fans reacted indignantly to the album, which was too adapted to the market, and Roversi also spoke of "industrial rather than cultural decisions"; in retrospect, however, it was recognized as a cornerstone of Dallas' work, including in terms of music. Ron , who later often worked as an arranger for Dalla, was on board for the first time as a musician.

The public image of Dallas changed parallel to his artistic development and brought him a large number of new fans, also thanks to his increasingly theatrical appearances and vocal improvisations.

Just two years later, the Cantautore was able to increase the success of its predecessor with his self-titled album. It reached number two in the charts and contained a number of later classics from his repertoire: Anna e Marco , L'ultima luna , Stella di mare , or Cosa sarà (in a duet with Francesco De Gregori ). The album ended with the formative L'anno che verrà , which creates a utopia for the end of the leaden years . Dalla had already presented some of the songs in advance on December 20, 1978, live at the RTSI , which years later also resulted in a video album. In the summer of 1979, the weekly magazine L'Espresso discussed the surprising success of the cultural phenomenon Dalla in a conversation with the journalist Giorgio Bocca .

The collaboration with Francesco De Gregori

Even before the successful album Lucio Dalla , the single Ma come fanno i marinai was released in December 1978 , written and sung in collaboration with Francesco De Gregori . The spontaneously created song was received very positively. Then the two Cantautori started the tour Banana Republic (eponymous for the live album that resulted from it), with which they filled stadiums all over Italy. It was the first time that Cantautori presented their music to a mass audience in stadiums; as pioneers of this new connection between musicians and audiences, Dalla and De Gregori became atypical rock stars. The live album contains ten songs, including several cover versions.

The 80s

From Dalla to found Stadio

The next album, Dalla , was released in September 1980. With a rockier style, Dalla made it to the top of the charts for the first time, the result of an undeterred creative phase. The songs it contained were well received by fans and critics alike, especially noting Futura , which, according to the musician, was made at Checkpoint Charlie in Berlin. Cara and La sera dei miracoli . The defining single was Balla balla ballerino , the story of a pacifist dancer. The theologian Vito Mancuso described the song Meri Luis as one of Dallas' most important.

With the Q disc , Dalla released a mini album / EP in 1981 in a new sound carrier format developed by the RCA. The four-track release is considered a continuation and at the same time the conclusion of his two previous albums. The first title Telefonami tra vent'anni from it became the most famous; an instrumental version of You've Got a Friend by Carole King concluded. At the same time, Dalla worked as a producer for an album by Renzo Zenobi , Telefono elettronico , on which he can also be heard as a guest singer.

At the end of 1981, Dallas companion band decided to start an independent parallel career and gave the band Stadio the go-ahead with the release of their own single . The name was inspired by the stadium rehearsals and performances during the Banana Republic tour, with Gaetano Curreri as the front man. In 1982 Carlo Verdone dedicated his film Borotalco to Lucio Dalla, for which he, Curreri and Giovanni Pezzoli contributed the title song Grande figlio di puttana . The song won the David di Donatello and the Nastro d'argento for best film song. Dalla praised Verdone for the film.

1983 , Viaggi organizzati , Bugie

The 1983 album , released that same year, was again a great sales success and a number one album, but didn't quite convince the critics. Dalla himself admitted that while recording the album he was otherwise busy and not tuned to the album. That year he wrote the title song with Lontano da dove for the film of the same name by Stefania Casini and Francesca Marciano .

In 1984 the Cantautore took a new musical direction and separated from Stadio. The album Viaggi organizzati was created in collaboration with the musician Mauro Malavasi . It reached the top of the chart again. A hit from it was Tutta la vita , which was sung in English by Olivia Newton-John . Other important titles were Tu come eri , Stornello and Washington . In 1985 Dalla teamed up again with Stadio and released the new album Bugie . After the success of the single Se io fossi un angelo , the album also sold as well as its predecessors. In the instrumental piece Tania del circo Dalla played the saxophone, with the jazz player Franco D'Andrea on the piano. He also wrote the title Lunedifilm , which the Rai used as the theme song for film screenings and which is included on the Stadio album Canzoni alla radio .

The international success of Caruso

In March 1986, Dalla started a short international tour with Stadio, which ended in the USA. To mark the occasion, the Rai aired a special about the concert at Village Gate, New York on March 23, 1986, and Dallas Experiences in the United States. The double live album DallAmeriCaruso emerged from this concert, the only unreleased song containing Caruso . This title over the last days of Enrico Caruso brought the Cantautore an extraordinary success. After the Targa Tenco as the best song of the year in Italy, it sold millions of times around the world and became a classic of the Italian song. Among the interpreters of the countless cover versions are Mercedes Sosa , Celine Dion , Michael Bolton , Lara Fabian , Julio Iglesias , Andrea Bocelli and Luciano Pavarotti ; In a list of the best-known Italian songs abroad presented at the Sanremo Festival in 2008, Caruso came second after Nel blu dipinto di blu by Domenico Modugno . According to Dallas statements, the song was created during a trip to Sorrento , where he stayed in the same hotel room as the famous tenor years earlier. From the hotel staff he heard the story of the love between the seriously ill Caruso and one of his students, which inspired him to write the song. Due to the Neapolitan passages, Dalla initially felt unable to sing the song herself.

The collaboration with Gianni Morandi

In June 1988 the collaboration album Dalla / Morandi was released in collaboration with Gianni Morandi , another number-one success with earlier songs by the two musicians as well as several new duets. The first single was Vita , written by Mogol and Mario Lavezzi , and especially for Morandi it represented a revitalization of his career. According to Lavezzi, the new songs were written especially for the project with Morandi, since the idea for the album was spontaneous and without any preparatory work had been hit. The tour that followed the album also took the musicians out of Italy and was a great success. Stadio was there one last time as a backing band. The conclusion of the tour at the Greek Theater in Syracuse was broadcast live on Rai 1 , directed by Gabriele Salvatores . Music critic Gino Castaldo noticed the stark contrast between the two musicians, who embodied completely different directions in Italian music.

The 90s

Attenti al lupo and other stories

Cambio ("change") was the title of the next album, which was released in October 1990. The programmatic title underscored Dallas’s desire for constant development. This change took place in the course of the 1990s and heralded the later pop phase of Cantautore. However, regardless of the changes, it still attracted a mass audience. With the single Attenti al lupo (written by Ron) Dalla reached the top of the single charts for the first time, and the album was able to build on the previous successes. According to journalist Giancarlo Trombetti, Ron was originally intended as the singer for Attenti al lupo himself, but Dalla managed to persuade him to let him do the song. Due to the great success of the song, other songs on the album were overshadowed, such as Le rondini , Bella , È l'amore and Comunista (which was created with Roberto Roversi).

On October 25 of that year, Dalla met Federico Fellini on a television show . During the conversation Fellini told of his experiences at a Dalla concert; When he was surprised that someone like Fellini would come to his concerts, the director said that everyone should see one at some point. In fact, Fellini had already included Dalla in his 1986 film Ginger and Fred , in a scene with doppelgangers of well-known personalities.

Between 1991 and 1992 Dalla went on the Cambio tour, during which he also met the young cantatore Samuele Bersani .

Henna and the success of Canzoni

After the live album Amen , the studio album Henna followed at the end of 1993 , the title song of which Dalla himself named as one of his favorite songs. In the television series Roxy Bar of Red Ronnie the song was presented at unprecedented style with a completely black screen. Other songs on the album are Latin lover , Domenica , Liberi , Cinema (with the participation of Marcello Mastroianni ) and Merdman as well as the final track Treno about the development of the post-communist states of Eastern Europe.

In the same year, Lucio Dalla was awarded the Premio Librex Montale literary prize in the Poetry for Music category (introduced in 1991) . Other winners in this category include Paolo Conte , Francesco Guccini , Fabrizio De André , Franco Battiato and Ivano Fossati . On this occasion he met the poets Alda Merini and Leandra D'Andrea , with whom he became friends.

In 1996, Canzoni appeared , representing Dallas' final turn to pop. The album was preceded by the single Canzone , the text of which Samuele Bersani had worked on and which made it into the top 10 of the single charts. Other successful songs from the album were Ayrton (dedicated to Formula 1 driver Ayrton Senna ) and Tu non mi basti mai . Canzoni surpassed the success of Cambio again. As a ghost track , the album contained a new version of Disperato erotico stomp , followed by the religious hymn Vieni, spirito di Cristo , interpreted by the young Franciscan Alessandro Fanti. In addition, at the time, Dalla directed Peter and the Wolf by Sergei Prokofiev . After this brief excursion into classical music, he turned to dance music and brought out ten remixes of some of his well-known songs on Lucio Dalla - Dance Remixes .

The recent work with Roversi and the album Ciao

In the summer of 1998 Lucio Dalla and Roberto Roversi worked together again when Roversi's piece Enzo re from 1974 was performed with music by Dalla. The event was supported by the University of Bologna and initiated a series of events on the occasion of Bologna's status as European Capital of Culture 2000. The work tells the story of King Enzios , son of Frederick II , and his capture by the citizens of Bologna. In addition to a number of students, Ugo Pagliai and Paolo Bonacelli also acted as actors , while Dalla performed some of his songs himself. He put together the album Enzo re from six songs , which was never officially released, but was given to the university as a gift. The piece was performed several times later. The songs from the unreleased album did not appear until 2013 in the posthumous compilation Nevica sulla mia mano , which is about Dallas' entire collaboration with Roversi.

In 1999, Dalla was awarded an honorary doctorate in literature and philosophy from the University of Bologna . In September of that year he released his next album, Ciao , his ninth number one success. In addition to the title track, it contained songs like What a Beautiful Day , Trash , Non vergognarsi mai , Là and Scusa . In addition, Dalla had re-recorded his old song in 1999 at the turn of the millennium . The album was followed by a similarly successful tour.

The 2000s

Between pop and opera

The new millennium was ushered in with the album Luna Matana , which was released in October 2001. The song Kamikaze (with Gianluca Grignani on guitar) caused a stir because it was interpreted by many as a reaction to the terrorist attacks of September 11th . The Corriere della Sera speculated in an article that Dallas record company had therefore prevented the song from being released as a single. BMG Ricordi defended this decision, while Dalla himself stated that there was no reference to the terrorist attacks; rather, the song refers to kamikaze pilots in World War II. Other tracks on the album are Siciliano , sung with Carmen Consoli , Notte americana and Agnese delle Cocomere . The title of the album refers to the bay of Cala Matana on the island of San Domino (Tremiti), where Dallas' house and studio are located.

In 2003 Dalla turned back to opera and wrote and staged Tosca - Amore disperato, his own version of Giacomo Puccini's Tosca . In collaboration with Mina he recorded the song Amore disperato . This was included on the album Lucio . The Tosca musical was first performed on October 23, 2003 in Rome, after its first presentation in Castel Sant'Angelo on September 27.

The compilation 12000 lune was released in 2006 and contained three CDs. The unpublished songs Stella, Sottocasa and Dark Bologna were also included. Once again the musician managed to reach the top of the chart. This year Dalla was also represented in the book Complice la musica by Fernanda Pivano , in which the author processes interviews with 30 cantautori.

Experience as a theater director

In February 2007, Dalla began a collaboration with Marco Tutino , director of the Municipal Theater in Bologna, and with producer Gianni Salvioni on a free editing of the ballet Pulcinella (1920) by Igor Stravinsky , which the opera Arlecchino (1917) by Ferruccio Busoni was combined , with Marco Alemanno as the main actor. Dalla described his choice of pieces as a backlash to consumer pressure from the market.

Together with Salvioni, the musician also worked on Peter and the Wolf and the DVD for the live album 12000 lune , on which the songs were recorded with a string quartet . In June 2007 he had his next pop album Il contrario di me follow. The album was also published as a supplement to the La Repubblica newspaper . Songs on the album were Due dita sotto il cielo (dedicated to the motorcycle racer Valentino Rossi ), the religious INRI , Malinconia d'ottobre and Rimini .

2008 staged Lucio Dalla The Beggar's Opera by John Gay , with he and Angela Baraldi and Peppe Servillo ( Avion Travel worked). The piece debuted in Bologna on March 29th of that year. Dalla had made changes to the text and transported the piece from 18th century London to today's Bologna. The Bolognese dialect is given a lot of space, the music is inspired by Handel and Purcell . The DVD for the play was again produced by Gianni Salvioni. The next release was the double live album LucioDallaLive - La neve con la luna .

On January 11, 2009, Dalla appeared in a television program on the tenth anniversary of Fabrizio De André's death and sang his song Don Raffaè together with actor Marco Alemanno . Again with Alemanno, he took part in the Teatrocanzone festival in honor of Giorgio Gaber in the summer and performed the song Io mi chiamo G. In October 2009, Dalla announced the single Puoi sentirmi? the new studio album Angoli nel cielo an. It also includes Questo amore , Gli anni non aspettano and Fiuto (duet with Toni Servillo ).

The last few years

The new project with De Gregori

In early 2010, a surprise concert by Dalla and Francesco De Gregori in Nonantola was announced under the name Work in progress . This performance was followed by a short tour. It was only their second tour together since Banana Republic 30 years ago; in between they only had one major joint appearance at the New Year's concert in Assisi , which the Rai broadcast in 1998. Dalla had been publicly considering a new project with De Gregori for a long time and on June 24, 2009 De Gregori appeared as a surprise guest at a Dalla concert.

In contrast to the previous tour, the concerts no longer took place in stadiums, but mostly in public places. The extended tour also included a major appearance at the traditional Concerto del Primo Maggio (2011). This new collaboration resulted in the double live album Work in Progress , with the three unpublished songs Non basta saper cantare , Gran turismo and Gigolò . To make it clear that it was not just a new edition of the old tour, but something new, Dalla and De Gregori did without their old hit Ma come fanno i marinai . The last joint appearance of the two and the end of the tour was on May 20, 2011 in Saint Vincent .

The last release and the return to Sanremo

Two years after the last album, Dalla released the compilation Questo è amore in November 2011 . The double album contains love songs from 1971 to 2009, plus the new single Anche se il tempo passa (Amore) and a new version by Meri Luis (in a duet with Marco Mengoni ).

At the end of January 2012 Rolling Stone magazine compiled the list of the 100 most beautiful Italian albums of all time , with Dalla at number 40 with Lucio Dalla from 1979. On February 14th of that year, Dalla returned to the stage of the Sanremo Festival after 40 years , alongside Pierdavide Carone and with the song Nanì . He was also active as a singer and conductor of the festival orchestra. The song landed in fifth place in the finals on February 18; it was when Dalla had his last television appearance. On February 27, 2012, he started his new European tour from Lucerne , which took him first to Zurich and on February 29 to Montreux , where he gave his last concert.

Sudden death

Lucio Dalla died on March 1st, 2012 at the age of 68 in his hotel room in Montreux after a heart attack . His partner Marco Alemanno found him dead in bed. The death news was first announced on Twitter by the monks of the Basilica of San Francesco at 12:10 p.m.

From the morgue in Lausanne , the body was first transferred to Dallas House in Bologna. On March 3, he was laid out in the Palazzo d'Accursio . Both Bologna and the Isole Tremiti municipality pronounced mourning. The funeral took place on March 4th (Dallas 69th birthday) in the Basilica of San Petronio in front of more than 50,000 people. The ceremony was broadcast live on the Internet and on a regional television station, and the burial took place at the Cimitero Monumentale della Certosa di Bologna . In 2013 his remains were cremated and buried near the graves of Giosuè Carducci and Giorgio Morandi . The grave was designed by Antonello Paladino and bears the last sentence of the song Cara as an inscription : “Buonanotte, anima mia, adesso spengo la luce e così sia” (“Good night, my soul, now I will turn off the light and so be it”) ).

Dallas music colleagues often expressed their sadness and dismay, including Paolo Conte , Francesco Guccini , Antonello Venditti , Francesco De Gregori , Franco Battiato , Ivano Fossati , Mogol , Eros Ramazzotti , Renato Zero , Claudio Baglioni , Adriano Celentano , Pino Daniele , Eugenio Finardi , Jovanotti , Vasco Rossi and Ligabue . Roberto Vecchioni recited and analyzed L'anno che verrà on television , and Red Canzian ( Pooh ) wrote a letter to Dalla in his autobiography. Colleagues from theater and film also spoke up, such as Dario Fo , Paolo and Vittorio Taviani , Eugenio Scalfari , Dacia Maraini and Michele Serra . Then there were Gaetano Curreri, Luca Carboni , Samuele Bersani, Ron and Gianni Morandi .

In July 2017, the city of Rome had a memorial plaque for Lucio Dalla put up on his home in Trastevere .

The estate and the foundation

The Dallas estate was estimated at around 100 million euros and included the copyrights to 581 songs, the 2,400 m² house in Bologna, the houses in Sicily and the Tremiti Islands as well as other real estate, the yacht Brilla & Billy (with recording studio) and Shares in two companies. In the house there were also works of art (including a work by Gustav Klimt ) and musical memorabilia with an estimated value of 3 million euros.

Since there was no will, the inheritance was divided among five Dallas cousins (fourth degree relatives), who were also left with the decision to set up a foundation . Dallas partner Marco Alemanno, who had lived with him for several years, had no legal right to an inheritance. During the 2012 edition of the festival dedicated to Giorgio Gaber in Viareggio , the Fondazione Gaber and the Fondazione De André launched a call to the heirs to quickly set up a foundation, signed by more than 80 representatives from the arts and music.

In July 2013, the heirs released part of the house in Bologna for sale to pay inheritance expenses; the following year also the house in Milo , Sicily , and the yacht to finance the foundation. An auction was started for this purpose in September 2014. By the end of the month, however, there were insufficient offers for the properties; the yacht went to an entrepreneur from Naples.

The foundation, the Fondazione Lucio Dalla , was founded on February 26, 2014 with headquarters in Bologna. The main objective is to maintain the cultural legacy of Dallas.

In February 2020, the foundation announced that it would donate a bust to mark Lucio Dallas’s birthday and place it on Piazza Cavour in Bologna. The bust was commissioned by the deceased's cousin, Kino Zaccanti, and made by the artist Antonello Paladino.

Private life

The Cantautore declared himself a member of the political left and took part in various events. At the same time he was an avowed Catholic Christian . He never confirmed his suspected homosexuality himself. In an interview with Pietro Savarino in the LGBT magazine Lambda in 1979, Dalla declared that he did not belong to any “sexual sphere”.

Other activities and interests Dallas

Movie and TV

From the 1960s onwards, Dalla appeared in numerous films, often singing his own songs. After a series of musical comedies, he had an appearance in 1967 in The Subversives by Paolo and Vittorio Taviani . With this role, he was nominated for best actor at the Venice International Film Festival (the prize ultimately went to Ljubiša Samardžić for A Serbian Morning ). Dalla roles were increasingly offered in various Italian films. In addition, he was commissioned for film music, for example by Michelangelo Antonioni , Mario Monicelli , Pupi Avati or Michele Placido . Dalla himself was a big movie lover, with a cinematograph and a collection of over 250 DVDs. In a 2008 interview, he stated that he preferred film to music.

Dallas' television experience began in 1977 with the play Il futuro dell'automobile e altre storie (starring Roversi), which also aired on television. In January 2002 he appeared together with Sabrina Ferilli as the presenter of the Saturday evening show La bella e la bestia on Rai 1 . In addition to appearing on various programs, Dalla also worked as a television writer. His pen included Taxi (Rai 3), Te voglio bene assaje (Rai 1) and Mezzanotte angeli in piazza (Rai 1). In 2003, Dalla was offered the artistic direction of the Sanremo Festival by the Rai , which in the end did not materialize.

literature

Like many of his fellow musicians, Dalla also tried his hand at writing and in 2002 published the book Bella Lavita at Rizzoli , which contained eleven short stories. Another book followed in 2008, Gli occhi di Lucio , this time by Bompiani and in collaboration with Marco Alemanno; it is partly autobiographical, partly dedicated to Benvenuto Cellini .

university

Dalla was appointed full professor at the University of Urbino in 2002 . He was a lecturer at the sociological faculty and held the chair for tecniche e linguaggi pubblicitari ("advertising techniques and language"). This experience resulted in the 2004 book Gesù, San Francesco, Totò: la nebulosa della comunicazione , which comprised a cycle of lectures on communication in the academic year 2002/2003. Guest lecturers such as Alessandro Bergonzoni , Oliviero Toscani , Giampiero Solari and Davide Paolini also contributed to the book. Another series of lectures on the subject of modernity was planned by Dalla from April 2012 , with a focus on Georg Simmel . In 2006, Dalla was also a visiting professor at the Scuola Normale Superiore ( Pisa ) and the Catholic University of the Sacred Heart ( Milan ). Dallas' academic career is similar to that of Roberto Vecchioni , who taught communication studies at the University of Pavia , or Francesco Guccini , who taught Italian at Dickinson College, University of Bologna .

painting

Lucio Dalla was very enthusiastic about art. He had many contacts with well-known artists, such as Michelangelo Pistoletto , Mimmo Paladino or Luigi Ontani. One of his favorite artists was Amico Aspertini , to whom he dedicated the song Amico . In Bologna, Dalla ran the No Code gallery , which opened in 1998. In an interview, he gave the Transavantgarde and Caravaggio as well as German Expressionism as his preferences . in his apartment in Bologna Dalla had pictures by Gustav Klimt , Andy Warhol and Amedeo Modigliani .

Sports

Dalla was also enthusiastic about sports, with a particular interest in basketball and football . On the occasion of his death, the Gazzetta dello Sport dedicated the front page to him. He was a supporter of FC Bologna and the Virtus Pallacanestro Bologna (basketball). In 2008, Dalla wrote Un uomo solo può vincere il mondo the official anthem of the Italian team at the Summer Olympics . He was also interested in motorsport and owned a Porsche 911 Carrera. Dalla took part in the Mille Miglia three times (here with a Porsche 356 Carrera), in 1999 and 2000 with Alessandro Bergonzoni and in 2003 with Oliviero Toscani .

politics

Political and social engagement often played a role in the Dallas song texts, especially those from the Roversi period. In January 2008 the Cantautore gave an interview to the Catholic online magazine Petrus , in which he declared that he was neither a Marxist nor a communist, but instead relied on Josemaría Escrivá de Balaguer , which he soon revoked. In fact, he had voted for the communist party and Enrico Berlinguer in the past , as he explained in a 1997 interview. Dalla did not deny his closeness to the political left in his last years either, but he was always critical of it.

Discography

Albums

Studio albums

- 1999 (1966; ARC)

- Terra di Gaibola (1970; RCA)

- Storie di casa mia (1971; RCA)

- Il giorno aveva cinque teste (1973; RCA)

- Anidride solforosa (1975; RCA)

| year | title |

Top ranking, total weeks, awardChart placementsChart placements (Year, title, rankings, weeks, awards, notes) |

Remarks | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

| 1976 | Automobili |

IT22 (3 weeks) IT |

- | - | - |

RCA

2012 number 69 (1 week) on the FIMI charts |

| 1977 | Come è profondo il mare |

IT9 (35 weeks) IT |

- | - | - |

RCA

2012 place 65 (2 weeks) on the FIMI charts |

| 1979 | Lucio Dalla |

IT2 (71 weeks)IT |

- | - | - |

RCA

2001 in Edition Dischi d'oro place 69 (2 weeks) of the FIMI charts 2012 place 33 (7 weeks) |

| 1980 | Dalla |

IT1 (38 weeks)IT |

- | - | - |

RCA

2012 number 43 (7 weeks) on the FIMI charts |

| 1981 | Lucio Dalla / Q-disc |

IT2 (21 weeks) IT |

- | - | - |

Qdisc format with four titles included

|

| 1983 | 1983 |

IT1 (26 weeks) IT |

- | - | - | |

| 1984 | Viaggi organizzati |

IT1 (18 weeks) IT |

- | - | - |

Pressing

|

| 1986 | Bugie |

IT1 (26 weeks) IT |

- | - |

CH11 (9 weeks) CH |

Pressing

|

| 1988 | Dalla / Morandi |

IT1 (43 weeks) IT |

- | - | - | |

| 1989 | Dalla / Morandi in Europe |

IT18 (4 weeks) IT |

- | - | - |

with Gianni Morandi

RCA |

| 1990 | Cambio |

IT1 (34 weeks) IT |

- | - |

CH16 (21 weeks) CH |

Pressing

2012 place 76 (2 weeks) on the FIMI charts |

| 1993 | Henna |

IT5 (15 weeks) IT |

- | - |

CH35 (4 weeks) CH |

Pressing

|

| 1996 | Canzoni |

IT1 (51 weeks) IT |

- | - |

CH17th (23 weeks)CH |

Pressing

sales: + 25,000 |

| 1999 | Ciao |

IT1 (22 weeks) IT |

- | - |

CH31 (5 weeks) CH |

Pressing

|

| 2001 | Luna Matana |

IT4 (24 weeks) IT |

- | - | - |

BMG

|

| 2003 | Lucio |

IT3 (19 weeks) IT |

- | - | - |

BMG

|

| 2007 | Il contrario di me |

IT8 (19 weeks) IT |

- | - | - |

RCA / Sony BMG

|

| 2009 | Angoli nel cielo |

IT18 (13 weeks) IT |

- | - | - |

Pressing Line / Sony

|

gray hatching : no chart data available for this year

Live albums

| year | title |

Top ranking, total weeks, awardChart placementsChart placements (Year, title, rankings, weeks, awards, notes) |

Remarks | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

| 1979 | Banana Republic |

IT1 (39 weeks)IT |

- | - | - | |

| 1986 | DallAmeriCaruso |

IT4th (28 weeks)IT |

- | - | - |

RCA

2009 place 4 (15 weeks) of the FIMI charts 2000 in Edition Dischi d'oro place 19 (11 weeks) sales: + 30,000; IT 2012 gold |

| 1992 | Amen |

IT4 (8 weeks) IT |

- | - | - |

Pressing

|

| 2008 | La neve con la luna ... |

IT26 (8 weeks) IT |

- | - | - | |

| 2010 | Work in progress |

IT4 (60 weeks) IT |

- | - | - |

with Francesco De Gregori

|

| 2013 | In quella notte di stelle |

IT47 (4 weeks) IT |

- | - | - |

posthumously, with Stefano Di Battista Jazz Quartet

|

gray hatching : no chart data available for this year

Compilations (selection)

| year | title |

Top ranking, total weeks, awardChart placementsChart placements (Year, title, rankings, weeks, awards, notes) |

Remarks | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

| 1985 | The best of Lucio Dalla |

IT10 (18 weeks) IT |

- |

AT38 (2 weeks) AT |

CH43 (3 weeks) CH |

RCA

CH chart entry 2000 2012 position 12 (2 weeks) in the FIMI charts and AT chart entry |

| 1998 | Gli anni 70 |

IT16 (9 weeks) IT |

- | - | - |

RCA

|

| 2002 | Caro amico ti scrivo ... |

IT3 (51 weeks)IT |

- |

AT70 (2 weeks) AT |

CH29 (5 weeks) CH |

AT and CH chart entry 2012

Sales: + 60,000; IT 2013 platinum |

| 2006 | 12000 lune |

IT1 × 2

(79 weeks)IT |

- | - |

CH75 (1 week) CH |

Sales: + 100,000;

IT 2016 double platinum |

| 2010 | Gli album originali |

IT78 (1 week) IT |

- | - | - | |

| 2011 | Questo è amore |

IT9 (13 weeks) IT |

- | - |

CH46 (2 weeks) CH |

|

| 2012 | Successi… Emozioni e magia |

IT71 (1 week) IT |

- | - | - | |

| Qui dove il mare luccica |

IT4th (72 weeks)IT |

- | - | - |

Sales: + 50,000

|

|

| 2013 | Roberto Roversi - Nevica sulla mia mano |

IT70 (1 week) IT |

- | - | - | |

| 2014 | Grandi interpreti italiani - Lucio Dalla |

IT89 (1 week) IT |

- | - | - | |

| 2015 | Trilogia |

IT76 (4 weeks) IT |

- | - | - | |

| 2018 | Duvudubà |

IT10 (14 weeks) IT |

- | - | - | |

Singles (selection)

Note: In the week around Dallas death (February 27 - March 4), 28 of his songs hit the single charts at the same time.

| year | Title album |

Top ranking, total weeks, awardChart placementsChart placements (Year, title, album , rankings, weeks, awards, notes) |

Remarks | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

| 1971 | 4 march 1943 Storie di casa mia |

IT1 (20 weeks)IT |

- | - | - |

2012 6th place (5 weeks) in the FIMI charts.

Sales: + 15,000 IT 2014 gold |

| 1972 | Piazza grande |

IT10 (8 weeks)IT |

- | - | - |

2012 place 7 (5 weeks) on the FIMI charts.

Sales: + 30,000 IT 2014 platinum |

| 1979 | Ma come fanno i marinai Banana Republic |

IT6 (19 weeks) IT |

- | - | - |

with Francesco De Gregori

|

| 1988 | Dimmi dimmi Dalla / Morandi |

IT11 (8 weeks) IT |

- | - | - |

with Gianni Morandi

|

| 1990 | Attenti al lupo Cambio |

IT1 (20 weeks)IT |

- | - |

CH25 (2 weeks) CH |

|

| 1994 | Liberi henna |

IT19 (2 weeks) IT |

- | - | - | |

| 1996 | Canzone Canzoni |

IT6th (7 weeks)IT |

DE79 (5 weeks) DE |

- |

CH42 (1 week) CH |

2012 place 16 (4 weeks) of the FIMI charts

CH chart entry 2012 sales: + 15,000; IT 2014 gold |

| 2011 | Meri Luis Questo è amore |

IT19 (1 week) IT |

- | - | - |

with Marco Mengoni

|

| 2012 |

Caruso DallAmeriCaruso (1986) |

IT2 (8 weeks)IT |

DE61 (1 week) DE |

AT43 (1 week) AT |

CH16 (3 weeks) CH |

DE and AT chart entry 2015

Sales: + 30,000; IT 2013 platinum |

| L'anno che verrà Lucio Dalla (1979) |

IT9 (5 weeks)IT |

- | - |

CH54 (1 week) CH |

Sales: + 30,000;

IT 2017 platinum |

|

| Tu non mi basti mai Canzoni (1996) |

IT12 (4 weeks)IT |

- | - | - |

Sales: + 15,000;

IT 2014 gold |

|

| Anna e Marco Lucio Dalla (1979) |

IT14th (4 weeks)IT |

- | - | - |

Sales: + 30,000;

IT 2014 platinum |

|

| Futura Dalla (1980) |

IT19th (3 weeks)IT |

- | - | - |

Sales: + 25,000;

IT 2019 gold |

|

| Come è profondo il mare Come è profondo il mare (1977) |

IT20 (3 weeks) IT |

- | - | - | ||

| Se io fossi un angelo Bugie (1986) |

IT25 (2 weeks) IT |

- | - | - | ||

| Le Rondini Cambio (1990) |

IT28 (2 weeks) IT |

- | - | - | ||

| Disperato erotico stomp Come è profondo il mare (1977) |

IT29 (2 weeks)IT |

- | - | - |

Sales: + 25,000;

IT 2017 gold |

|

| Balla balla ballerino Dalla (1980) |

IT31 (2 weeks) IT |

- | - | - | ||

| Cara Dalla (1980) |

IT33 (2 weeks)IT |

- | - | - |

Sales: + 25,000;

IT 2019 gold |

|

| Cosa sarà Lucio Dalla (1979) |

IT42 (2 weeks) IT |

- | - | - |

with Francesco De Gregori

|

|

| Ayrton Canzoni (1996) |

IT46 (2 weeks) IT |

- | - | - | ||

| Nuvolari Automobili |

IT48 (1 week) IT |

- | - | - | ||

| Ciao Ciao (1999) |

IT53 (2 weeks) IT |

- | - | - | ||

| L'ultima luna Lucio Dalla (1979) |

IT59 (2 weeks) IT |

- | - | - | ||

| La sera dei miracoli Dalla (1980) |

IT63 (… Where.)IT |

- | - | - |

Sales: + 25,000;

IT 2019 gold |

|

| Quale allegria Come è profondo il mare (1977) |

IT69 (1 week) IT |

- | - | - | ||

| Il gigante e la bambina Storie di casa mia (1971) |

IT73 (1 week) IT |

- | - | - | ||

| Apriti Cuore Cambio (1990) |

IT78 (1 week) IT |

- | - | - | ||

| Felicità Dalla / Morandi |

IT79 (1 week) IT |

- | - | - |

with Gianni Morandi

|

|

| Milano Lucio Dalla (1979) |

IT87 (1 week) IT |

- | - | - | ||

| Occhi di ragazza Terra di Gaibola (1970) |

IT90 (1 week) IT |

- | - | - | ||

| Telefonami tra vent'anni Lucio Dalla / Qdisc (1981) |

IT98 (1 week) IT |

- | - | - | ||

gray hatching : no chart data available for this year

Filmography

- 1965: Questo pazzo, pazzo mondo della canzone - Director: Bruno Corbucci , Giovanni Grimaldi

- 1965: Altissima pressione - Director: Enzo Trapani

- 1966: Keep your hands off the doll (Europa canta) - Director: José Luis Merino

- 1967: The Subversives (I sovversivi) - directed by Paolo and Vittorio Taviani

- 1967: Blue Beans for a Hallelujah (Little Rita nel West) - Director: Ferdinando Baldi

- 1967: I ragazzi di Bandiera Gialla - Director: Mariano Laurenti

- 1967: Franco, Ciccio e le vedove allegre - Director: Marino Girolami

- 1967: Quando dico che ti amo - Director: Giorgio Bianchi

- 1968: The Super Sensual (Questi fantasmi) - Director: Renato Castellani

- 1969: Amarsi male - Director: Fernando Di Leo

- 1972: Il santo patrono - Director: Bitto Albertini

- 1973: Il prato macchiato di rosso - Director: Riccardo Ghione

- 1975: La mazurka del barone, della santa e del fico fiorone - Director: Pupi Avati

- 1979: Banana Republic - Director: Ottavio Fabbri

- 2006: Quijote - Director: Mimmo Paladino

- 2008: Artemisia Sanchez - Director: Ambrogio Lo Giudice

Honors

- In 1986 the asteroid (6114) Dalla-Degregori was named after the duo.

- Order of Merit of the Italian Republic (Commander) on December 27, 1986 on the initiative of the President of the Council of Ministers

- Order of Merit of the Italian Republic (Grand Officer) on November 3, 2003 on the initiative of the President of the Republic

- Honorary doctorate from the University of Bologna in Discipline delle arti, della musica e dello spettacolo on July 9, 1999

literature

- Roberto Roversi: Il futuro dell'automobile. Dodici testi per Lucio Dalla. Anteditore, Verona 1976.

- Simone Dessì (Ed.): Lucio Dalla. Il futuro dell'automobile, dell'anidride solforosa e di altre cose. 60 testi di canzoni. Savelli, Rome 1977.

- Stefano Micocci (Ed.): Lucio Dalla. Canzoni. Lato Side, Rome 1979.

- Fernanda Pivano: Complice la musica. BUR, 2006.

- Umberto Piancatelli: Lucio Dalla - La storia dietro ogni canzone. Barbera, 2013.

- Paolo Jachia: Lucio Dalla, giullare di Dio. Un profilo artistico. Edizioni Ancora, 2013.

- Carlo Poma: Lucio Dalla Vero. Persiani, Bologna 2015, ISBN 978-88-98874-19-4 .

Web links

- Official website

- Lucio Dalla at Discografia Nazionale della Canzone Italiana

- Lucio Dalla at Allmusic (English)

- Literature by and about Lucio Dalla in the catalog of the German National Library

- Lucio Dalla in the Internet Movie Database (English)

- Lucio Dalla - Cantautore in the fast lane - Jazz Collection -Podcast of the SRF with many audio samples

supporting documents

- ↑ Francesco Chiari: LUCIO DALLA / La Bologna jazz anni '60, la consacrazione e l'ultimo viaggio a Montreaux. In: IlSussidiario.net. March 4, 2012, Retrieved August 29, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Perikles Monioudis: Lucio Dalla, the pioneer of Musica leggera, dies on tour in Switzerland: Se io fossi un angelo. In: nzz.ch . March 1, 2012, accessed September 1, 2017 .

- ^ Andrea Conti: Lucio Dalla tra amici e duetti speciali. March 1, 2012, accessed August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ a b c Augusto Pasquali: Dizionario della musica italiana (= Enciclopedia tascabile il Sapere ). S. 30 .

- ↑ Play it again, Lucio. (No longer available online.) In: GQ . March 2, 2012, archived from the original on September 10, 2012 ; Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ^ È morto Lucio Dalla, stroncato da un infarto. In: TG1. Rai, March 2, 2012, accessed August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Maghdi Abo Abia: Lucio Dalla sui giornali di tutto il mondo. (No longer available online.) In: Giornalettismo.com. March 1, 2012, archived from the original on October 14, 2013 ; Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Come è profondo il mare. In: Antiwarsongs.org. Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ^ A b c Gianni Leoni: “Il papà di Lucio era Giuseppe” La 'cugina' Fiorella Fantuzzi: “Ecco la verità sull'infanzia di Dalla”. In: Il Resto del Carlino . March 11, 2012, accessed August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ a b Gilberto Dondi: Dalla, voci sulla paternità “Voglio qui Lucio”. In: il Resto del Carlino. March 10, 2012, accessed August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ^ Daniele Ferrazza: Addio a Lucio Dalla, studiò tre anni a Treviso al Collegio Pio X. In: La tribuna di Treviso. March 2, 2012, accessed August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ^ Morto Lucio Dalla. (No longer available online.) In: Leggo.it. March 2, 2012, archived from the original on October 19, 2013 ; Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ^ Morto Lucio Dalla: addio al grande cantante italiano. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on June 22, 2012 ; Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ a b c LUCIO Dalla, morto di infarto in Svizzera. March 1, 2012, accessed August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ a b c Giorgio Dell'Arti: Biografia di Lucio Dalla. In: Corriere della Sera. Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Delia Allegretti: Pupi Avati: "Dalla mi ha bruciato, Fellini folgorato". In: Larena.it. March 26, 2012, accessed August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ a b c d e f g Il “magico quotidiano” by Lucio Dalla, cantautore felice. (No longer available online.) In: IlFoglio.it. March 1, 2012, archived from the original on December 22, 2012 ; Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ^ Curiosità e tanto caos: so si raccontava Lucio Dalla. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on October 14, 2013 ; Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ^ Giorgio Dell'Arti: Antenna . In: La Stampa . June 22, 2007, p. 45 .

- ↑ La Puglia piange Lucio Dalla, Vendola: "Un amico della regione". March 1, 2012, accessed August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Angela Benassi: Doctor Dixie Jazz Band: "oldest in the world". (No longer available online.) In: europacheverra.eu. Archived from the original on October 15, 2013 ; Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ^ Tiziano Tarli: Beat italiano . Castelvecchi, 2005, ISBN 88-7615-098-6 , p. 143 ( google.de ).

- ^ Andrea Montemurro: Lucio Dalla poesia e canzone. In: quotidianogiovanionline.it. March 2, 2012, accessed August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Lucio Dalla. (No longer available online.) In: LaStampa.it. February 2, 2012, archived from the original on October 14, 2013 ; Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Lucio Dalla, a Torino il suo primo contratto discografico. In: cronacaqui.it. March 2, 2012, accessed August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Luca Indemini, Paolo Ferrari: Lucio Dalla: “Un luogo del cielo chiamato Torino”. In: La Stampa.it. March 2, 2012, accessed August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Agata Rita Iudicelli: Addio a Lucio Dalla. (No longer available online.) In: amiciziasenzafrontiere.it. Archived from the original on September 2, 2017 ; Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ a b c d Claudio Fabretti: Lucio Dalla. Tra la via Emilia e la Luna. In: Ondarock.it. Retrieved August 30, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Biografia di Lucio Dalla. (No longer available online.) In: fullsong.it. Archived from the original on March 6, 2013 ; Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Massimo Catalano in March 1979 during the radio program Spazio X , Rai 2 , quoted in Stefano Micocci: Lucio Dalla - Canzoni . Lato Side, 1979, pp. 46 .

- ^ Lucio Dalla, addio al "poeta" bolognese. In: diariodelweb.it. March 2, 2012, accessed August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Marco Paini, Dario Formentin: Interview with Gino Paoli. In: Tutto , No. 3, 1979.

- ↑ a b Lucio Dalla in Simone Dessì (ed.): Il futuro dell'automobile, dell'anidride solforosa e di altre cose . Savelli, 1977, p. 101 .

- ↑ La scomparsa di Lucio Dalla: la vita ei video. In: rockol.it. March 1, 2012, accessed August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ a b Lucio Dalla, biografia Raiuno Raidue. (No longer available online.) February 2000, archived from the original on October 16, 2013 ; Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Andrea Maioli: Dalla, Gianni Cavina: “Io cantavo, lui recitava, insuccesso clamoroso…” In: Il Resto del Carlino. March 3, 2012, accessed August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ^ Davide Turrini: A Bologna i cd di Lucio Dalla diventano introvabili. In: Il Fatto Quotidiano. March 4, 2012, accessed August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ^ Addio Lucio. A Sanremo 1971 la canzone delle polemiche. In: ilsole24ore.com . Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Lucio Dalla: lo strano destino legato al 4 marzo. In: ilSussidiario.net. March 4, 2012, accessed August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ a b Marcello Giannotti (ed.): L'Enciclopedia di Sanremo . Gremese Editore, 2005, p. 66 .

- ↑ Lucio Dalla - Tra il mare e le stelle. In: Spot and Web. Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Lucio Dalla - Storie di casa mia. In: discogs.com. Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ^ Vittorio Capecchi: Paola Pallottino: scrivere testi per Lucio Dalla. In: inchiestaonline.it. March 7, 2012, accessed August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ a b Il mondo di Lucio Dalla. November 18, 2011, accessed August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ^ Il dolore di Bologna per la morte di Lucio Dalla. Morandi: pietrificato. (No longer available online.) In: virgilio.it . Archived from the original on July 5, 2012 ; Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Montagne verdi. In: Galleria della canzone. March 4, 2012, accessed August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ^ Avvenire.it parla del Servizio mobile di Piazza Grande. (No longer available online.) In: piazzagrande.it. February 9, 2012, formerly in the original ; Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian). ( Page no longer available , search in web archives )

- ↑ La piazza - Svolgimento temi - Esame di Stato 2001. (No longer available online.) In: atuttascuola.it. Archived from the original on October 14, 2013 ; Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Lucio Dalla . In: Gino Castaldo (ed.): Enciclopedia della canzone italiana . Curcio, 1990, p. 467 .

- ↑ Lucio Dalla: Il Giorno Aveva Cinque Teste. In: Debaser. Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ^ Carlo Cazzaniga: Parco Lambro 1976: quando anche Milano ebbe la sua Woodstock… ma all'italiana… (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on October 14, 2013 ; Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Musica sotto shock: addio a Lucio Dalla. In: TGcom24. March 1, 2010, accessed August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Roberto Roversi in Simone Dessì (ed.): Il futuro dell'automobile, dell'anidride solforosa e di altre cose . Savelli, 1977, p. 19 .

- ↑ Interview with Lucio Dalla in Claudio Bernieri: Non sparate sul cantautore vol. 2º . Mazzotta, 1978, p. 80 .

- ^ Antonio Maria Bonaccorso: Com'è profondo il mare: omaggio a Lucio Dalla. (No longer available online.) Arci CreAttiva Aci Castello, April 27, 2012, archived from the original on October 16, 2013 ; Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ^ Roberto Roversi in Claudio Bernieri: Non sparate sul cantautore vol. 2º . Mazzotta, 1978, p. 105 .

- ↑ Antonella Beccaria: L'irresistibile vita di Lucio Dalla, talento prestato alla musica. E non solo. In: Il Fatto Quotidiano. March 15, 2012, accessed August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Maria Laura Giulietti: Come è il mare profondo - biografia del capolavoro di Lucio Dalla. In: lisolachenoncera.it. April 27, 2012, accessed August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ^ Roberto Vecchioni: La canzone d'autore in Italia. In: Treccani.it. March 1, 2012, accessed August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ L'anno che verrà. In: hitparadeitalia.it . Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ DVD supplement of the Corriere della Sera from March 9, 2012.

- ↑ Giorgio Bocca: Quella Chiacchierata con Bocca. In: L'Espresso. March 1, 2012, accessed August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ^ Francesco De Gregori in Stefano Micocci: Lucio Dalla - Canzoni . Lato Site, 1979, p. 71 .

- ↑ Stefano Ciavatta: L'eccezione Dalla: raffinato, per le masse e amato all'estero. In: Linkiesta.it. March 1, 2012, accessed August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ^ Fabrizio Zampa in Il Messaggero , quoted in Stefano Micocci: Lucio Dalla - Canzoni . Lato Site, 1979, p. 17 .

- ^ Christian Tipaldi: L'Italia perde uno tra i più grandi musicisti, Lucio Dalla. (No longer available online.) In: WorldMagazine.it. March 1, 2012, archived from the original on October 14, 2013 ; Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ^ Mario Luzzatto Fegiz: Banana Republic spiegato da De Gregori. May 16, 2012, accessed August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Dalla: una febbre di musica che scaccia gli stranieri. La Stampa, August 1, 1981, accessed May 12, 2015 .

- ↑ La Canzone d'Autore Italiana. (No longer available online.) March 1, 2012, archived from the original on August 22, 2014 ; accessed on August 28, 2017 (English).

- ↑ Lucio Dalla prevede il XXI secolo (incontro a Catania, primavera 1997). (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on September 23, 2015 ; Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Alberto Sebastiani: “L'amore che ho cantato come non l'avevate mai ascoltato prima”. November 8, 2011, accessed August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Gaetano Curreri in the television program Il mondo di Lucio Dalla , October 15, 2010 - Dixit Stelle on RAI Storia.

- ↑ Orlando Sacchelli: Vent'anni fa un film dedicato a Dalla: Borotalco. In: IlGiornale.it . March 1, 2012, accessed August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Verdone ricorda Lucio Dalla. “Mi fece i complimenti per Borotalco”. In: Repubblica.it. March 1, 2012, accessed August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ^ Lontano da dove. (No longer available online.) In: Corriere.it. Archived from the original on January 14, 2012 ; Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Alessandro Alicandri: Lucio Dalla, le sue canzoni più amate. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on May 2, 2015 ; Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ^ Gino Castaldo: Dalla a New York 'Is good, Really'. In: La Repubblica.it. March 26, 1986, accessed August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Enrico Deregibus (Ed.): Dizionario della canzone italiana . S. 136 .

- ↑ Lucio Dalla, un percorso artistico inarrivabile. (No longer available online.) March 1, 2012, archived from the original on May 21, 2013 ; Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ^ Tutti i Caruso del mondo. (No longer available online.) March 2, 2012, archived from the original on March 4, 2012 ; Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ^ Sanremo 2008: le dieci canzoni italiane più famose nel Mondo. In: Rockol.it. February 28, 2008, accessed August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Lucio Dalla svela la nascita di 'Caruso'. In: Rockol.it. April 18, 2002, accessed August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Dalla, Caruso il suo successo mondiale. (No longer available online.) In: IlMessaggero.it. March 1, 2012, archived from the original on October 15, 2013 ; Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ^ A b Galleria della canzone italiana - Dalla / Morandi. Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ^ Gino Castaldo: Dalla - Morandi, colpo vincente. In: La Repubblica.it. June 14, 1988. Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ^ Dal Teatro Greco 'Dalla - Morandi'. Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ^ Piero Vittoria: Caro amico ti scrivo ... ciao Lucio! March 3, 2012, accessed August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ^ Giancarlo Trombetti: Ricordo di Lucio, di Giancarlo Trombetti. (No longer available online.) March 1, 2012, archived from the original on September 14, 2012 ; Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Marco Marozzi: Così Dalla metterà all'asta la musica di Roversi. In: Repubblica.it. Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ a b Andrea Silenzi: Come inventories la canzone la storia di Lucio Dalla. Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Emanuela Giampaoli: Le canzoni, i film, la memoria, so Dalla ritorna in piazza. In: Repubblica.it. Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ^ Gino Castaldo: Lucio Dalla, genio di canzoni qual è per te la più bella? (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on October 15, 2013 ; Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Lucio Dalla ricordato in uno speciale su Roxy Bar tv. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on October 14, 2013 ; Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ^ Premio Librex Montale. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on November 21, 2010 ; Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ^ Morto il cantautore Lucio Dalla, la musica italiana perde un maestro. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on October 14, 2013 ; Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Attenti a quel frate, canta per Dalla. (No longer available online.) In: Corriere.it. Archived from the original on October 14, 2013 ; Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Lucio Dalla: una vita da cantautore. In: mtv.it. Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Dalla dance: un disco con i remix delle canzoni di Lucio. In: Rockol.it. Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Al via Bologna 2000, capitale europea della Cultura. In: Repubblica.it. January 21, 2000, accessed August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Mario Luzzatto Fegiz: Dalla: il pop inaridisce, ora mi do al teatro. (No longer available online.) In: Corriere.it. Archived from the original on October 14, 2013 ; Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Lucio Dalla e Riccardo Majorana. Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ^ Emilio Marrese: Dalla inedito, ecco il carteggio con Roversi e le loro canzoni censurate. In: Repubblica.it. Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Esordio con primato by Ciao. In: Rockol.it. Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Lucio Dalla, un grande artista. In: Lapiazzarimini.it. Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ^ Mario Luzzatto Fegiz: No della casa discografica al "kamikaze" di Dalla. (No longer available online.) In: Corriere.it. Archived from the original on October 14, 2013 ; Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Lucio Dalla e la BMG Ricordi correggono il 'Corriere della Sera'. In: Rockol.it. September 25, 2001, accessed August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Ferruccio Maria Fata: Rispettiamo la realtà storica delle Isole Tremiti. March 24, 2012, accessed August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ^ Intervista a Lucio Dalla: La mia Tosca. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on October 14, 2013 ; Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ 'Lucio', esce domani il disco di Dalla nato in un mese. In: Rockol.it. October 30, 2003, accessed August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Lucio Dalla. (No longer available online.) Tosca Amore Disperato, archived from the original on March 10, 2013 ; Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Com'è profondo il cordoglio. (No longer available online.) In: Rolling Stone. March 2, 2012, archived from the original on May 3, 2012 ; Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ^ Lucio Dalla trasporta Pulcinella a New York. (No longer available online.) In: Corriere.it. Archived from the original on October 14, 2013 ; Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Silvana Mazzocchi: Lucio Dalla: “Non so fare niente” e diventa regista di un melodramma. In: Repubblica.it. April 9, 2006, accessed August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ^ Gino Castaldo: Il nuovo disco di Lucio Dalla: “Meglio venderlo in edicola”. In: Repubblica.it. June 28, 2007, accessed August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ^ Giuseppe Pennisi: L'opera del mendicante e l'Italia di Veltroni. April 6, 2008, accessed August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ^ Francesco Lora: La contaminazione di Dalla rinverdisce il Mendicante. Retrieved August 28, 2017 .

- ↑ Lucio Dalla - La neve con la luna - Live. In: Rockol.it. February 26, 2008, accessed August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ^ Che tempo che fa - Speciale Fabrizio De André. Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Le edizioni precedenti. (No longer available online.) Festival Giorgio Gaber, archived from the original on February 13, 2014 ; Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Pippo Augliera: Lucio Dalla: dagli angoli nel cielo per un dialogo con il cuore. (No longer available online.) November 1, 2009, archived from the original on October 14, 2013 ; Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Gino Castaldo: Dalla e De Gregori, meglio dopo 30 anni “E ora faremo anche un disco”. In: Repubblica.it. January 23, 2010, accessed August 30, 2017 .

- ↑ Luca Zanini, Giuseppina Manin: Notte ad Assisi, canzoni e polemiche. (No longer available online.) In: Corriere.it. January 2, 1998, archived from the original on October 14, 2013 ; Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ^ Gino Castaldo: De Gregori e Dalla insieme trent'anni dopo Banana Republic. In: Repubblica.it. January 2, 2010, accessed August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Sandra Cesarale: De Gregori Lucio Dalla e l'Unità d'Italia. (No longer available online.) In: Corriere.it. April 16, 2011, archived from the original on October 14, 2013 ; Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Andrea Morandi: ReTournée Dalla e De Gregori dopo trent'anni ma non è un'operazione nostalgia. In: Repubblica.it. May 5, 2010, accessed August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Lucio Dalla e Francesco De Gregori - Il calendario del tour 2010/2011. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on September 23, 2015 ; Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Lucio Dalla, esce 'Questo è amore'. September 11, 2011, accessed August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ^ I 100 dischi italiani più belli di semper per Rolling Stone. IlPost.it, January 30, 2012, accessed August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ^ È morto Lucio Dalla: a Sanremo l'ultima apparizione in tv. In: Repubblica.it. Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ^ Addio a Lucio Dalla, l'ultimo concerto, Montreux 29-2-2012. In: Repubblica.it. Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ a b Deborah Dirani: L'eredità di Lucio Dalla a cinque cugine. Nulla a Marco Alemanno. Bagnasco: di fronte ai defunti si prega. In: Il Sole 24 Ore. March 6, 2012, accessed August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Silvia Sperandio: È morto Lucio Dalla. Colpito da un infarto, what in Svizzera per una serie di concerti. In: Il Sole 24 ore. March 1, 2012, accessed August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Lucio Dalla 1943-2012. In: Repubblica.it. Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Davide Monastra: Lucio Dalla: oggi i funerali, visibili solo in diretta streaming. (No longer available online.) March 4, 2012, archived from the original on October 23, 2013 ; Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Davide Turrini datum = 2012-03-05: “La Chiesa non condanna il peccatore”: il funerale di Dalla diventa un caso politico. In: IlFattoQuotidiano.it. Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Gaia Giorgetti, Luca Orsi: Lucio Dalla è stato cremato Ceneri inumate in Certosa. (No longer available online.) In: Il Resto del Carlino. October 23, 2013, archived from the original on October 29, 2013 ; Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Francesco De Gregori: “Non mi sento di parlare”, Vasco Rossi: “Era il nostro padre famiglia”. In: Repubblica.it. March 1, 2012, accessed August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ^ Gabriele Ferraris: Gianni Morandi “Io e Lucio due ragazzi insieme alla partita”. In: LaStampa.it. March 2, 2012, accessed August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ^ Targa in memoria di Lucio Dalla. In: rerumromanarum.com. July 2017. Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ^ Emiliano Liuzzi: Quello che Dalla non avrebbe voluto: guerra sull'eredità e niente Fondazione. In: IlFattoQuotidiano.it. April 1, 2012, accessed August 30, 2017 .

- ↑ a b Davide Turrini: Lucio Dalla, asta flop: invendute le sue tre case. Lo yacht a un fan di Napoli. In: IlFattoQuotidiano.it. October 3, 2014, accessed August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ^ Gianpaolo Balestrini, Giorgiana Cristalli: Lucio Dalla: non c'è testamento, tutto agli eredi. In: ANSA.it . July 5, 2012, accessed August 30, 2017 .

- ↑ Una fondazione per Dalla come quelle Gaber-De André. In: LaStampa.it. July 23, 2012, accessed August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Emanuela Astolfi: Eredità Lucio Dalla, l'appartamento dove viveva Alemanno è in vendita. In: Il Resto del Carlino. July 23, 2013, accessed August 30, 2017 .

- ↑ Lucio Dalla, in vendita la villa in Sicilia del cantautore bolognese: qui produceva il vino lo Stronzetto dell'Etna (PHOTO). June 10, 2014, accessed August 30, 2017 .

- ↑ Vanno All'asta le case di Lucio Dalla. In: Il Sole 24 Ore. August 8, 2014, accessed August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ^ Davide Turrini: Lucio Dalla, case e barca finiscono all'asta. Con i ricavi nascerà una fondazione. In: IlFattoQuotidiano.it. August 8, 2014, accessed August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Lucio Dalla, l'annuncio della Fondazione il 4 marzo. Escluso Marco Alemanno. In: Il Resto del Carlino. February 26, 2014, accessed August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Bologna, una panchina di Lucio Dalla in Piazza Cavour. February 12, 2020, accessed February 13, 2020 (Italian).

- ^ È morto Lucio Dalla, cattolico senza riserve. (No longer available online.) In: LaPerfettaLetizia.com. March 1, 2012, archived from the original on April 8, 2012 ; Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Piero Valesio: Dalla gay? Vietato parlarne. In: IlFattoQuotidiano.it. March 4, 2012, accessed August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ^ È morto Lucio Dalla, uno dei poeti della musica italiana. La7 , March 1, 2012, accessed August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Piero Negri: Dalla Confesso: non mi sento omosessuale. (No longer available online.) In: LaStampa.it. March 6, 2012, archived from the original on July 4, 2017 ; Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ^ Paolo Nice: Nuovo Cinema Lucio Dalla. In: Sky.it . March 1, 2012, accessed August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ^ Ilaria Abate: Lucio Dalla, voce e corpo sul grande schermo. In: Cinemonitor.it. March 5, 2012, accessed May 25, 2020 (Italian).

- ↑ Sonia Arpaia: Lucio Dalla, Paolo Taviani: “Era un sovversivo nell'anima”. (No longer available online.) In: Doppioschermo.it. March 1, 2012, archived from the original on April 9, 2014 ; Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ^ Luigi Locatelli: Ricordando Lucio Dalla attore di cinema: dai Taviani ad Avati a Mimmo Paladino. In: Nuovo Cinema Locatelli. March 1, 2012, accessed August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Lucio Dalla e il cinema: dalle musiche per Monicelli al set con i fratelli Taviani. (No longer available online.) In: Doppioschermo.it. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015 ; Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Paolo Giordano: Il controritratto di Lucio Dalla. Source stoccate agli intoccabili. In: IlGiornale.it. March 3, 2012, accessed August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Lucio Dalla - Luna Matana. In: Namir.it. Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Morto Lucio Dalla colpito da un infarto. In: Dagospia.com. March 1, 2012, accessed August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Lucio Dalla - Il futuro dell'automobile. Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ La 'bella' Sabrina Ferilli insieme a Lucio Dalla. November 25, 2001, accessed August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Marcello Giannotti (ed.): L'Enciclopedia di Sanremo . Gremese, 2005.

- ↑ Saverio Grimaldi: Quando i cantanti si mettono a fare gli scrittori. (No longer available online.) In: Panorama.it. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015 ; Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Lucio Dalla - Bella Lavita. In: Il libro della settimana. Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Lucio Dalla: in libreria “Gli occhi di Lucio”. (No longer available online.) In: Musicroom. Archived from the original on September 2, 2017 ; Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ^ Genio Fiorentino: Lucio Dalla canta Benvenuto Cellini. In: Artelabonline.it. May 12, 2008, accessed August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ^ Alberto Sofia: Lucio Dalla, artista e comunicatore della modernità: il ricordo di Urbino. (No longer available online.) In: il Ducato. University of Urbino, March 1, 2012, archived from the original on July 2, 2012 ; Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Dalla Lucio - Gesù, san Francesco, Totò: la nebulosa della comunicazione. In: Edizioni Franco Angeli. Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Lucio Dalla, artista e comunicatore della modernità: il ricordo di Urbino. (No longer available online.) In: Il Ducato. University of Urbino, archived from the original on April 6, 2015 ; Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Lucio Dalla alla Normale. In: Firenze.it, Portals Giovani. March 5, 2006, accessed August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ^ Quella volta che Lucio Dalla tenne lezione in Cattolica. In: Cattolica news. March 1, 2012, accessed August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Franca Porciani: Il "prof" Vecchioni insegna la protesta. (No longer available online.) In: Corriere.it. Archived from the original on January 1, 2016 ; Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ^ Un altro giorno è andato: Francesco Guccini si racconta a Massimo Cotto. Giunti, Florence 1999, ISBN 88-09-02164-9 , p. 57.

- ↑ Dalla L a Dalla. (No longer available online.) In: ArteeLuoghi.it. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015 ; Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Lucio Dalla: brano inedito dedicato al pittore Amico Aspertini. In: rockol.it. September 26, 2008, accessed August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ^ Valerio Cappelli: Dalla: e adesso apro una galleria d'arte. (No longer available online.) In: Corriere.it. January 20, 1998, archived from the original on April 2, 2015 ; Retrieved August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ Emiliano Liuzzi: 40mila persone per l'ultimo saluto a Dalla. Le lacrime di Jovanotti e Renato Zero. In: IlFattoQuotidiano.it. March 3, 2012, accessed August 28, 2017 (Italian).

- ↑ La Gazzetta saluta Lucio Dalla, con una prima pagina speciale. In: Gazzetta.it. March 1, 2012, accessed August 31, 2017 (Italian).