La battaglia di Legnano

| Work data | |

|---|---|

| Title: | The battle of Legnano |

| Original title: | La battaglia di Legnano |

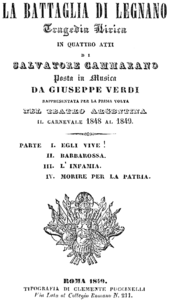

Title page of the libretto, Rome 1849 |

|

| Shape: | Opera in four acts |

| Original language: | Italian |

| Music: | Giuseppe Verdi |

| Libretto : | Salvatore Cammarano |

| Literary source: | La Bataille de Toulouse by Joseph Méry |

| Premiere: | January 27, 1849 |

| Place of premiere: | Rome , Teatro Argentina |

| Playing time: | approx. 1 ¾ hours |

| Place and time of the action: | Milan and Como , 1176 |

| people | |

|

|

La battaglia di Legnano ( The Battle of Legnano ) is an opera in four acts by Giuseppe Verdi based on a libretto by Salvatore Cammarano . The premiere took place on January 27, 1849 at the Teatro Argentina in Rome . According to today's musicological standards, the work is Verdi's only original Risorgimento opera.

action

The background to the plot is the historical battle of Legnano , in which Emperor Friedrich Barbarossa and his army suffered a heavy defeat and had to make peace with the Lombard cities, to which he granted limited autonomy. In the text of the opera, anachronistic references to the current situation in Italy shimmer through.

First act: "Egli vive" - He lives

First picture: Parts of the rebuilt Milan not far from the city walls

The opera begins with an eight-minute prelude, the main melody of which becomes the main theme of the Lombard League . A choir of warriors from the Lombard League sing “Viva Italia!”. The text of this opening choir expresses the current desire of the Italians for an agreement. Arrigo, who has joined the Veronese warriors, greets Milan in a scene and cavatina . When Rolando arrives with the men from Milan and recognizes his friend Arrigo, who was believed to be dead, the latter tells him that he was only wounded and that he was captured. After the appearance of the Milanese consuls, all warriors swear to defend Milan with their blood against the Austrians ("Austro", sic!).

Second picture: Shady place under groups of trees, near the moats

Lida, Arrigos' former fiancé and current wife Rolandos, has since given birth to a son. In one scene and cavatina, she laments the death of her family, but wants to go on living out of a sense of duty. At that moment, the scheming Marcovaldo, a German prisoner of war, joins them and confesses his love for her. After Lida refused him, Lida's maid Imelda announced Arrigo’s arrival. Lida, who still loves Arrigo, is excited. When Rolando arrives accompanied by Arrigo, Marcovaldo observes Lida's undisguised affection for Arrigo. The scene is interrupted by a herald who reports that an army of Emperor Barbarossa is approaching. Rolando hurries away with the herald. Arrigo, who has since learned that Lida is married to Rolando, blames her for breaking her oath to belong to him forever. Lida tries to justify herself by saying that she believed him dead and that she swore her father on his deathbed to marry Rolando. Arrigo doesn't believe her and wants to find death in battle.

Second act: "Barbarossa"

A room in Como Town Hall

Despite the earlier battles against Como, Milan has agreed to a common alliance against Emperor Friedrich Barbarossa. In the performance choir of the military leaders and the Como magistrate, one is still full of hatred for Milan. Rolando and Arrigo appear as ambassadors to persuade Como to form an alliance against the emperor. The mayor of Como objects that they are contractually bound to the emperor. When Arrigo's question as to what answer they should bring back, Barbarossa himself replied: “Io la darò” (“I will give it”). At a sign from the emperor, the doors are opened and the imperial army can be seen approaching to subdue Milan again. All present swear war to the death ("Guarra a morte!")

Third act: "L'infamia" - The shame

First image: underground vault in the Basilica of Sant'Ambrogio in Milan

The death knights, an association of warriors who want to fight to the death for Italy, have gathered to take a common oath. Arrigo joins this association and swears the oath together with the death knights.

Second picture: Apartments in Rolandos Castle

Lida has since learned that Arrigo has joined the Death Knights. In a letter she asks him for one last discussion. Rolando says goodbye to Lida to go to war. He asks them to raise their son in love for God and the fatherland. When Arrigo arrives, Rolando asks him to protect his wife and child and says goodbye to Arrigo. Marcovaldo has intercepted Lida's letter to Arrigo and hands it to Rolando. He thinks he has been cheated and wants revenge.

Third picture: A room high up in the tower

Arrigo writes a letter to his mother. Lida goes to see him to say goodbye, confessing her love to him once again, but at the same time declaring her renunciation out of duty to her son. Arrigo opens the door at the knock of Rolando, Lida hides on the balcony. During the argument with Arrigo, Rolando opens the shutters on the balcony, discovers Lida and casts her away. When Arrigo tries to plead her innocence, Rolando draws his sword, but thinks about a stronger vengeance. When the trumpets sound to collect for the battle, he condemns Arrigo to disgrace by locking him up with Lida in the tower chamber so that Arrigo cannot start the liberation struggle. Arrigo, who is watching the exodus of the army and the death knights from the balcony, can no longer bear this disgrace and rushes from the balcony with the exclamation “Viva Italia!”.

Fourth act: “Morire per la patria” - To die for the fatherland

Square in Milan in front of a church

Imelda reports to Lida that Arrigo survived the fall, got out of the river unharmed and joined the army against Barbarossa. In a large scene with a trio and a victory anthem, voices behind the stage proclaim: “Vittoria! Vittoria! ”(“ Victory! Victory!) ”. The second consul of Milan announced to the praying people that the imperial troops in front of Legnano had been defeated by the Lombard League. Emperor Barbarossa himself was torn from the saddle by Arrigo and is badly wounded or even dead. (In fact, Barbarossa only died in 1190 during the Third Crusade when he drowned in the Saleph River near Seleucia .) The fatally wounded Arrigo is brought by the death knights. In a final discussion, in the face of death, he assures Rolando that Lida has not been unfaithful to him. Rolando believes him and forgives. Arrigo dies to the sounds of the Te Deum in celebration of victory.

Instrumentation

The orchestral line-up for the opera includes the following instruments:

- Woodwinds : flute piccolo , flute , two oboes , two clarinets , two bassoons

- Brass : four horns , two trumpets , three trombones , cimbasso

- Timpani , percussion : bass drum , cymbals , snare drum , bell

- harp

- Strings

- Incidental music: six trumpets, four trombones, snare drum

Work history

Emergence

The year 1848 was the year of new beginnings and the Europe-wide revolutions. Italy had been fermenting for several years, and the unification movement saw the goal of freeing itself from Austrian and papal supremacy. In February 1848, after five days of street fighting, the Milanese were able to drive out the Austrian soldiers. The rulers were also expelled in Parma , Modena and Tuscany . Venice proclaimed itself an independent republic. Pope Pius IX , an opponent of the Italian unification efforts, fled Rome to Gaeta in the Kingdom of Naples-Sicily in November 1848 and was only able to return in spring 1850 with the help of French troops.

Verdi, who was in Paris in 1848, was a supporter of the unification movement and was looking for material for a patriotic opera. He initially thought of Edward Bulwer-Lytton's Rienzi, or The Last of the Tribunes ( Rienzi, the last of the tribunes ), a subject that Richard Wagner had already used in his opera Rienzi , which premiered in 1842 . Since Verdi's friend, the librettist Francesco Maria Piave , was serving as a soldier in the newly formed Venetian Guard, Verdi turned to Salvatore Cammarano, the librettist from Alzira . Cammarano advised against using Cola di Rienzo and instead suggested Joseph Méry's play La battaille de Toulouse as the basis of the plot , changing the setting and the historical context. No longer the Napoleonic era, but the war of the Lombard League against Emperor Friedrich Barbarossa from 1176 with the Battle of Legnano should form the background of the opera, enriched with "patriotic choirs, oaths and processions". This battle, in which the army of Friedrich Barbarossa suffered a severe defeat, had long since become a catchphrase of the unification movement and was specifically mentioned in the fourth stanza of the hymn Fratelli d'Italia composed the year before .

Méry's play dealt with the conflict that a French soldier who had disappeared after the Battle of the Nations was declared dead, but survived and continued to fight for his fatherland. Meanwhile his fiancée had become his best friend's wife. After seeing each other again, the woman and the soldier agreed to meet one last time before going to war again. An intriguer stuck this to the husband. Instead of stabbing the supposed rival, the husband imposed a terrible punishment on him for a soldier. He was no longer allowed to fight for his country. The soldier could not bear this shame and rushed out the window.

The opera's libretto is based on Méry's basic idea, with Cammarano and Verdi moving the opera's plot to the 12th century. As is known from the correspondence between Cammarano and Verdi, Verdi insisted on a personal appearance by Barbarossa in the second act and sketched, as usual, many parts of the libretto in prose, just as he intended the main female character to play a greater role than in Méry's play.

reception

The premiere in the Roman Teatro Argentina was only 13 days before the official proclamation of the Roman Republic in February 1849. The audience was so enthusiastic about the opera that the entire third act had to be repeated.

After the short-lived Roman Republic was crushed by Spanish and French invaders on July 3, 1849 and the Austrians ruled northern Italy again, the time of the Restoration began. Due to pressure from the censors , the place, time and characters of the plot had to be changed. The opera was moved to the time of Philip II of Spain and now dealt with the revolt of the Netherlands against the Duke of Alba , who replaced Barbarossa. After these changes, the opera was allowed to be played under the title L'assedio di Arlem .

Verdi considered revising the opera and commissioning a new libretto several times, but finally rejected this idea. With the establishment of the Kingdom of Italy in 1861, La battaglia di Legnano became popular again, but later, like many works by Verdi from his early creative period, it was forgotten. The work was only rediscovered in the course of the Verdi renaissance in the 20th century.

Discography (selection)

- Complete recording with Marco Stefanoni , Antonietta Stella , Franco Corelli , Ettore Bastianini , choir and orchestra of La Scala Milan under Gianandrea Gavazzeni , melodrama / Myoto / OPD, live recording 1961.

- Complete recording with Nicolai Ghiuselew , Katia Ricciarelli , José Carreras , Matteo Manuguerra , choir and symphony orchestra of ORF Vienna under Lamberto Gardelli , Philips 1977.

- DVD: with Cesar Hernandez, Giorgio Cebrian, Elisabete Matos, Manrico Signorini, Francesco Palmieri, choir and orchestra of the Teatro Massimo Bellini under Nello Santi , directed by Walter Pagliaro, Bongiovanni 2002.

literature

- Julian Budden: the work of an ardent patriot. Analysis in the supplement to the CD, recording by Philips 1977.

- Heinz Wagner: The great manual of the opera. 2nd edition, Florian Noetzel Verlag, Wilhelmshaven 1995, p. 739.

Web links

- La battaglia di Legnano : Sheet music and audio files in the International Music Score Library Project

- Libretto (Italian), Rome 1849. Digitized by the Conservatorio “Benedetto Marcello” Venice

- La battaglia di Legnano (Giuseppe Verdi) in the Corago information system of the University of Bologna

- Work information and libretto (Italian) as full text on librettidopera.it

- Action of La battaglia di Legnano on Opera-Guide landing page due to URL change currently not available

- Discography of La battaglia di Legnano at Operadis

- Brief information

Individual evidence

- ↑ Budden: Work of an ardent patriot. 1977, p. 32.

- ^ Mary Ann Smart: Verdi, Italian Romanticism, and the Risorgimento. In: Scott Balthazar (Ed.): The Cambridge Companion to Verdi. Cambridge University Press 2004, pp. 29-45. Here in particular p. 33 f.

- ↑ Budden: Work of an ardent patriot. 1977, p. 36.

- ^ Rein A. Zondergeld : La battaglia di Legnano. In: Piper's Encyclopedia of Musical Theater. Volume 6: Works. Spontini - Zumsteeg. Piper, Munich / Zurich 1997, ISBN 3-492-02421-1 , p. 422

- ↑ Budden: Work of an ardent patriot. 1977, p. 27 f.

- ↑ Budden: Work of an ardent patriot. 1977, pp. 29-31.

- ↑ Budden: Work of an ardent patriot. 1977, p. 32.

- ↑ Budden: Work of an ardent patriot. 1977, p. 32.

- ↑ Budden: Work of an ardent patriot. 1977, p. 34.