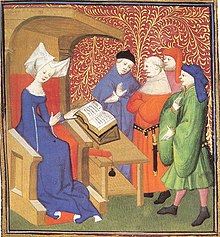

Christine de Pizan

Christine de Pizan or de Pisan (* 1364 in Venice ; † after 1429 , probably in Poissy ) was a French writer and philosopher. She is considered to be the first author of French literature who was able to make a living from her works. Her best-known work today is Le Livre de la Cité des Dames ( The Book of the City of Women ), which from today's perspective is one of the first feminist works in Europe and the trigger for the Querelle des Femmes .

Life and work

Born in Venice, the daughter of astrologer and physician Thomas of Pizzano, it came as a four year old girl to Paris when her father to astrologers and personal physician to King Charles V was appointed. She owed her father a good education in Latin , geometry and arithmetic , which she later expanded through extensive reading of older and contemporary, theological and profane literature in French and Latin.

At the age of fifteen Christine was married to the petty aristocratic royal secretary Étienne du Castel (1354-1390) and subsequently had three children with him.

After the death of her father in 1387 and that of her husband, who succumbed to an epidemic in 1390, she had to struggle with lengthy inheritance processes and the resulting financial problems. In addition to her children, she also had to care for her mother and two teenage brothers. Since a remarriage with such an attachment and without fortune was hardly conceivable, she remembered her poetic talent and began to write ballads , lais and rondeaus , taking Eustache Deschamps as a model. For her children she first wrote the educational book “Book of Wisdom”, which she dedicated to Philip the Bold , the Duke of Burgundy, a son of the French King John II , for the usual fee .

She then quickly won over other wealthy patrons to whom she dedicated and presented her works, including the French Queen Isabeau de Bavière and the Dukes Johann von Berry , Louis of Orléans and John Fearless of Burgundy , the successor of Philip the Bold, who also belonged to the royal family .

As a poet, Christine initially addressed love, although she particularly lamented the loss of her husband in a very personal way ( Ballades du veuvage , Cent ballades d'amant et de dame ). Later she wrote, not only in verse but also in prose , more doctrinal and philosophical works, e.g. B. the Fürstenspiegel L'Épître d'Othéa (1400) or the reflections on Fortuna's work in history and in her own life in La Mutation de Fortune (1403). In addition, she responded in politically motivated works to the civil wars in France of the intermittently deranged King Charles VI. (1380–1422), behind whom various people and parties, in particular the “ Bourguignons ” and “ Armagnacs ”, fought for power in the state and repeatedly involved England in their quarrels. (→ Civil War of the Armagnacs and Bourguignons ; Battle of Azincourt ) These works include Le Livre des faits d'armes et de chevalerie (1410); Lamentations sur les maux de la guerre (1410) and Le Livre de la paix (1413).

An apologetic biography (1404) of the patron of her father and great King Charles V , who, with the help of his capable general Bertrand du Guesclin, had almost pushed the English out of France and temporarily pacified the country, was also politically intended . Perhaps it was Christine who gave Karl the nickname “the sage” (“le Sage”).

In 1399 she criticized the misogyny of the men in her social environment, and in particular that of Jean de Meung in the rose novel , with which she unleashed the so-called Querelle du Roman de la rose , the first Parisian literary controversy in the history of French literature, in which she herself with her Épître au dieu d'amours (also 1399) intervened. In 1401 she wrote Le Dit de la rose , which describes the fictitious establishment of an "order of roses" protecting women. A treatise on the correct education of girls, Le Livre des trois vertus, dates from 1404 .

In 1405 she completed her most interesting work from today's perspective: Le Livre de la Cité des dames . In it, in response to a publication by Matthaeus von Boulogne and using the example of significant female figures from biblical and profane history, she points to the misunderstood abilities of women and develops the image of a utopian society in which women are granted equal rights. Here she writes u. a .:

“Those who have slandered women out of disapproval are petty minds who have met numerous women who are superior to them in their cleverness and refinement. They reacted with pain and displeasure, and so their great resentment led them to say bad things about all women ... But since there is hardly a significant work by a respected author that does not find imitators, there are even some who rely on copying embarrassed. They think it can't go wrong at all, since others have already said in their books what they want to say themselves - such as denigrating women; I know a lot of this variety. "

In addition, she showed in her main work how the negative statements of the scholars about the female gender affected women. She describes her own doubts in a fictional dialogue with God in which she first accuses him of “God created a wicked being with woman”, but then comes to the conclusion that “You [God] yourself, and that in a very special way that women [created ...] It's unthinkable that you should have failed in anything! " Her trust in God's wisdom allows her to overcome her self-doubt and encourage her to write The Book of the City of Women . She emphatically emphasizes her belief that “there cannot be the slightest doubt that women belong to the people of God as well as men”. (Quotes: The Book of the City of Women , p. 37 and p. 218)

From 1418, the beginning of one of the worst phases of the Hundred Years War , she lived in seclusion with her daughter Marie in the Dominican convent of Saint-Louis de Poissy . There she experienced the military accomplishments of Joan of Arc , the "Maid of Orléans", in 1429 , and in 1430, after a long period of silence, she dedicated a praise to her, the Dictié en l'honneur de la Pucelle . Thereafter nothing is known about them. Presumably she died in Poissy soon after 1430 .

For a long time Christine de Pizan was neglected in French literary historiography, but today she is by far the most productive and versatile of all authors of her generation. Literary and social scientists also value her as a women's rights activist avant la lettre .

Works

- Cent Ballades . 1399

- Epistre au Dieu d'amours . 1399

- Le Debat de deux amants . 1400

- Le Livre des trois jugements amoureux . 1400

- Le Dit de Poissy . 1400

- L'Epistre Othéa . 1400

- Lettres sur le Roman de la Rose . 1401

- Oraison Nostre Dame . 1402

- Le Livre du Chemin de longue estude . 1402

- Le Dit de la Pastoure . 1403

- Le Livre de la Mutacion de Fortune . 1403

- Epistre a Eustache Morel (= E. Deschamps). 1404

- Le Livre des faits et bonnes mœurs you say roy Charles V . 1404

- Le Livre du duc des vrais amans . 1404

- Le Livre de la Cité des Dames . 1405

- Le Livre des Trois Vertus or Le Trésor de la Cité des Dames . 1405

- Epistre a la Royne . 1405

- Le Livre de l'advision Cristine . 1405

- Le Livre de Prudence or Le Livre de la prod'homie de l'homme . 1405

- Le livre du corps de policie . 1407

- Le livre des fais d'armes et de chevalerie . 1410

- La Lamentacion sur les maux de la France . 1410

- Le Livre de la Paix . 1413

- Epistre sur la prison de la vie humaine . 1418

- Les Heures de contemplacion sur la Passion de Nostre Seigneur . 1420

- Dictié en l'honneur de la Pucelle or Le Dictié de Jehanne d'Arc . 1429

- German editions

- The book of the city of women . Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, Munich 1990, ISBN 3-423-02220-5

literature

- Francoise Autrand: Christine de Pizan , Fayard, Paris 2009, ISBN 978-2-213-63642-9

- Marilynn Desmond, Pamela Sheingorn: Myth, Montage, & Visuality in Late Medieval Manuscript Culture: Christine de Pizan's Epistre Othea . University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor 2003.

- Ursula Krechel : With the building blocks of her mind: Christine de Pizan . In: Strong and quiet. Pioneers . Jung and Jung, Salzburg / Vienna 2015, ISBN 978-3-99027-071-4 ; Paperback edition: btb, Munich 2017, ISBN 978-3-442-71538-1 .

- Régine Pernoud : Christine de Pizan . Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, Munich 1990, ISBN 3-423-11192-5

- Fee-Isabelle Rautert: Christine de Pizan between war and peace. The political writings 1402–1429 . Kovac, Hamburg 2005, ISBN 3-8300-2184-4

- Michael Richarz: ideal state and crisis of France in the political theory of Christine de Pizan . Logos, Berlin 2004, ISBN 3-8325-0784-1

- Jean.Yves Tilliette: Cristina (Christine) da Pizzano (de Pizan). In: Massimiliano Pavan (ed.): Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani (DBI). Volume 31: Cristaldi – Dalla Nave. Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, Rome 1985.

- Charity Willard: Christine de Pizan. Her Life and Works . Persea Books, New York 1984

- Margarete Zimmermann : Christine de Pizan . Rowohlt, Reinbek 2002, ISBN 3-499-50437-5

Web links

- Literature by and about Christine de Pizan in the catalog of the German National Library

- Literature by and about Christine de Pizan in the SUDOC catalog (Association of French University Libraries)

- Article in name, title and dates of the French Literature (main source for the section "Life and Creation")

- Biography and poems (french)

- Christine de Pisan: Livre de la mutation de fortune BSB (Cod.gall. 11)

Individual evidence

- ^ Gerhard, Ute .: Gender dispute and clarification. In this. (Ed.): Women's Movement and Feminism: A History Since 1789 . 2nd Edition. Beck, Munich 2012, ISBN 978-3-406-56263-1 , pp. 11 .

- ↑ Pizzano, where the father's family owned property, is a frazione from Monterenzio near Bologna, cf. Tilliette in the Dizionario biografico degli Italiani

- ↑ Wulf Hund : Racism in Context , p. 12

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Christine de Pizan |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Christine de Pisan; Cristina da Pizzano |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | French writer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 1364 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Venice |

| DATE OF DEATH | after 1429 |

| Place of death | unsure: Poissy |