Battle of Azincourt

Coordinates: 50 ° 27 ′ 49 ″ N , 2 ° 8 ′ 30 ″ E

| date | October 25, 1415 |

|---|---|

| place | About halfway between Abbeville and Calais in northern France; Azincourt (formerly Agincourt), France |

| output | English victory |

| consequences | The elite of the French army was destroyed. Henry V went to Calais instead of taking advantage of the spectacular success and marching to Paris |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

| Commander | |

| Troop strength | |

| between 6,000 and 9,000 English and Welsh people | between 14,000 and 36,000 French |

| losses | |

|

approx. 400 fallen, including the Duke of York |

around 8,000 fallen, including the connétable (commander in chief) of France, three dukes, 90 nobles and over 1,500 knights |

Chevauchées of the 1340s: Saint-Omer - Auberoche

Edward III. Campaign (1346/47): Caen - Blanchetaque - Crécy - Calais

War of the Breton Succession (1341–1364) : Champtoceaux - Brest - Morlaix - Saint-Pol-de-Léon - La Roche-Derrien - Tournament of Thirty - Mauron - Auray

France's allies : Neville's Cross - Les Espagnols sur Mer - Brignais

Chevauchées of the 1350s: Poitiers

Castilian Civil War & War of the Two Peter (1351–1375): Barcelona - Araviana - Nájera - Montiel

French counter-offensive: La Rochelle - Gravesend

Wars between Portugal and Castile (1369– 1385): Lisbon - Saltés - Lisbon - Aljubarrota

Battle for Northern France: Rouen - Baugé - Meaux - Cravant - La Brossinière - Verneuil

Jeanne d'Arc and the turn of the war: Orléans - Battle of the herring - Jargeau - Meung-sur-Loire - Beaugency - Patay - Compiegne - Gerberoy

The Battle of Azincourt ( French Bataille d'Azincourt , English Battle of Agincourt ) took place on October 25, 1415, on the day of Saint Crispian , near Arras in what is now the northern French department of Pas-de-Calais . The troops of King Henry V of England fought against the army of King Charles VI. of France , various French noblemen and the Armagnacs . It was one of the greatest military victories of the English over the French during the Hundred Years War .

The Battle of Azincourt is unusually well documented for a medieval battle. The precise location of the main battle is undisputed; There is uncertainty about the chronology only in the details. The number of battle participants, on the other hand, has long been a matter of dispute, as the chronicles differ widely. For nearly 600 years, however, there was consensus that the Anglo-Welsh army was vastly outnumbered by the French. Modern historians have often assumed a 4: 1 balance of power in favor of the French. Recent research by the British historian Anne Curry denies this. Deviating from the previous doctrine, she takes the view (based on the documented pay payments ) that the French army was only superior to the Anglo-Welsh army by a power ratio of 3: 2. The exact balance of power remains a matter of dispute.

The Battle of Azincourt is considered to be one of the most important battles in military history , because - as before the Battle of Crécy - foot troops armed with longbows played a decisive role in the outcome of the battle. The attack by the heavy French cavalry remained ineffective, not least because of the massive use of the long archers, ie the attack of the heavily armed French nobles was slowed down and impaired by their use. The military defeat of France was so lasting that Henry V was able to force the Treaty of Troyes on France in 1420 , which assured him of the claim to the French throne through the marriage of the French king's daughter Catherine of Valois .

background

Causes of the dispute

The starting point and main point of contention of the Hundred Years' War, which included the Battle of Azincourt, was the English claim to the French throne. The first phase of this war ended after the English victories in Crécy (1346) and Maupertuis (1356) with the Peace of Brétigny , concluded in 1360 , which ensured the rule of England over large parts of France. By 1396, the French were able to recapture a large part of the country they had lost to the English and secure it by means of a new peace treaty with England. Henry V, who ascended the English throne in 1413, renewed his claim to the French kingdom and resumed diplomatic talks, while at the same time recruiting an army of experienced soldiers paid directly by the English crown. After breaking off diplomatic negotiations, he and his army landed on August 14, 1415 in Harfleur (today the Seine-Maritime department ) in Normandy .

On the French side stood the insane King Charles VI. across from. Among his imperial administrators were the Duke of Burgundy , John Ohnefurcht , and the Duke of Orléans , Charles de Valois , who fought a power struggle with their parties of the Bourguignons and the Armagnacs that almost paralyzed the French side in the war against the English. The city of Harfleur, besieged by the Anglo-Welsh army, was not helped by a French army and the city surrendered on September 22nd. While one found after the fall of Harfleur mobilization of Lehnsheere in the French provinces instead, but the armies of the Dukes of Orleans and Burgundy would probably have fought each other at a meeting. So the army of the Burgundian Duke Johann Feart remained behind and the Connétable , Charles I. d'Albret , commanded the French armed forces.

The English March to Azincourt

About a third of the Anglo-Welsh army was dead or incapacitated after the week-long siege of Harfleur . With the rest of the army weakened from day to day by a dysentery epidemic , Henry V wanted to move to Calais , which had been the last bastion of the English crown in northern France since 1347. There he wanted to prepare for future fighting. The direct route from Harfleur to Calais was about 200 kilometers and led along the coast. Only the Somme presented a major obstacle on this path. To cross this river above the estuary, the Anglo-Welsh army moved further inland from October 13th.

Along the Somme , French troops had occupied the crossings in good time, so that the English armed forces had to penetrate further and further inland in search of a way to cross the Somme. She followed the course of the river, but the French army kept pace with her on the north bank of the Somme. Henry V therefore decided not to follow the course of the river any longer and crossed the Santerre plain in a forced march to shake off the French army. In the vicinity of Bethencourt and Voyennes they found two unguarded, albeit damaged, dams that allowed them to cross the Somme. Up to this point in time they had covered 340 km in twelve days. Therefore, Henry V let his army rest on October 20th. From October 21 to 24, the army covered a further 120 km. Henry V was aware that the French army had to be on their right flank. Scouts were able to confirm this assumption on October 24th. Although the French were already in order on October 24th, the battle did not take place because of falling darkness. The two armies camped within earshot of each other during the very rainy night.

equipment

The Battle of Azincourt is sometimes referred to as a confrontation between knights and archers. The heavily armored, mounted warriors of the Middle Ages are called knights in the broader sense of the word. In a narrower sense, knight is the name of a class to which many, but by no means all, medieval nobles belonged. For financial and family reasons, many aristocrats preferred to remain servants and thus knightly and weapon-bearing warriors throughout their lives . In Azincourt heavily armored cavalry, which was only used by the French side, only played a role at the beginning of the battle; the actual and decisive battle took place on foot between heavily armored nobles, not all of whom belonged to the knighthood. English historiography therefore differentiates between knights (= knights in the narrow sense) and men-at-arms (= heavily armored warriors who wore plate armor ). In German-language literature, the English term men-at-arms is also occasionally used for these warriors . In the following, this part of the fighters in the Battle of Azincourt is referred to as "armed men", a term also used by Hermann Kusterer, who translated John Keegan's analysis of the Battle of Anzincourt into German.

Equipment of the armed

The armed men of both armies each wore plate armor , a full armor that consisted of several dozen metal plates that were flexibly connected to one another by numerous straps, rivets and hinges and made it unnecessary to wear a shield . For many, chain mail under the plate armor protected armpits and genitals. The head was protected by a basin hood to which a movable visor was attached. Depending on the client's wealth, the tanks were made individually for him or consisted of several inherited or individually purchased items. The production of a custom-made harness usually took several months. The price differences between plate armor could be very large, but they usually cost at least as much as a craftsman at the time made over several years. Together with the helmet, the armor, which was distributed over the whole body, weighed between 28 and 35 kilograms. Well-crafted armor allowed its wearer to get on his horse without outside help or to get up again after a fall without any problems.

Equipment of the English longbowmen

Very little is known about the equipment of the English longbow archers essential to the outcome of the battle. Some of them may have been wearing short-sleeved chain mail over a padded doublet . The padded doublet had evolved from the gambeson worn under the chain mail . It was tight around the torso and arms and consisted of several layers of solid linen fabric, which was quilted lengthways. It was often padded with wool, wadding, felt, hemp, or hay. A doublet from the 1460s has been preserved and has 23 layers of linen and wool on the front and 21 layers on the back. Some sources report that the archers otherwise fought bareheaded and barefoot. They were far inferior in a direct fight with an armed man because of their other weapons and the poor protection their clothing offered. However, compared to a fighter wearing plate armor, they were considerably more posable.

Her decisive strength lay in the skilled use of the longbow . An archer had to be able to shoot at least ten arrows per minute to be accepted into the Anglo-Welsh army. The archers mastered different shooting techniques. This involved shooting arrows in such a way that they followed a high parabolic trajectory. Several rows of archers standing one behind the other could fire their arrows at the same time. This technique was mainly used when the enemy's attack should be slowed down by a dense swarm of arrows.

The arrows wore a wrought iron point. The so-called "war tip type 16" according to the classification of the British Museum was about five centimeters long, lanceolate with a flat elliptical cross-section and barely pronounced barbs . Based on modern attempts at shooting, it is known that these arrows could penetrate chain mail and plate armor. Bodkin points were also used , which due to their short, powerful square point could also penetrate plate armor and chain mail. Here, too, modern shooting tests have shown that arrows with a Bodkin point can penetrate a plate armor with a plate thickness of 1.5 mm at an impact angle of 50 degrees.

The arrows were transported in bundles of 24 arrows in linen containers. During the battle, the archer carried these either as a bundle in his belt or in a transport case. Often the archer stuck his arrows in the ground in front of him. Such tips, contaminated by soil, often led to serious inflammation of the wounds of those affected.

Battle formation and troop strength

The French battle formation

The French side is sometimes accused of having faced the English troops without preparing for battle, given their numerical superiority. However, a French battle plan has been preserved, which was presumably drawn up a few days before the Battle of Azincourt. Then the French planned a three-part battle formation in which the armed men stood in the middle. They were to be flanked by archers and crossbowmen, who were supposed to decimate the English archers with their arrows and bolts in the first minutes of battle. A cavalry of 1,000 men, also placed on the flanks , was supposed to overrun the archers and put them down. The main attacking forces in the second row were to be led by Charles I. d'Albret and the Dukes of Alençon , Orléans and Brittany . The two wings were to be under the command of Arthur de Richemont and Tanneguy du Chastel . According to this plan, Jean I de Bourbon , Jean II Le Maingre and Guichard II Dauphin, Grand Master of France , were in charge of the front line that was to fight after the cavalry attack .

The original order of battle was never implemented. The Duke of Brittany as well as Tanneguy du Chastel and the Count of Charolais (Philip the Good) appeared late or not at all on the battlefield. The high aristocrats present, on the other hand, demanded to be on the prestigious front line and refused to take a leadership role over the flanks or the rearguard . The dispute was resolved by letting the highest nobility and holders of the most important French major offices take up positions in the front line. She was to attack the Anglo-Welsh army on foot after an attack by mounted soldiers on the English archers. The dukes of Alençon and Bar were to lead the main attack forces. Assuming that eight thousand men each formed the vanguard and the main armed forces, then the vanguard and the main armed forces each consisted of eight ranks. The rearguard, or third line, were mounted men, whose job it should be to pursue the English and Welsh as soon as their line was destroyed by the mounted men, the vanguard and the main forces. Two divisions of about five hundred horsemen each were posted on the two wings. The French archers, who were placed on the front line of the wings according to the original plan, were now placed behind the armored soldiers. That made it almost impossible for them to intervene in the battle.

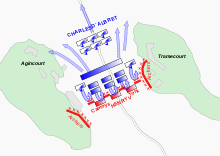

The English battle formation

On the English side, the battle was to be fought mainly on foot. The battle order consisted of three blocks, between which two groups of archers were probably placed. The right block was commanded by Edward of Norwich, 2nd Duke of York , the middle by Henry V and the left by Lord Thomas Camoys . The line of the armed was about four to five men deep. The wings were again made up of archers and may have been pulled forward a little. The archers were led by Sir Thomas Erpingham , a very experienced knight who had already served under Henry IV .

The Anglo-Welsh archers had carried sturdy stakes with them since the tenth day of the march, sharpened on both sides. Heinrich V had given the order to take them along because they were an effective measure against sudden attacks by riders. These piles were driven diagonally into the ground by the archers. According to analysis by John Keegan, it is most likely that the stakes were driven in six or seven rows, about three feet apart, at an angle. This allowed the archers the freedom of movement that later played a role in the course of the battle.

Troop strength

The number of those fighting on the French side has long been highly controversial, while there was broad consensus on the troop strength of the Anglo-Welsh side that it consisted of around 1,000 armed men and 5,000 archers. However, based on the documented English wages, Anne Curry is of the opinion that the British side is underestimated and assumes at least 1,593 armed men and 7,139 archers. What was unusual about the Anglo-Welsh army was therefore not its small size, but a composition in which the armed forces did not even make up a quarter of the troops.

Contemporary British sources cite 60,000 to 150,000 men on the French side, whereas contemporary French sources tend to downplay the number of those involved in the battle on the French side, naming between 8,000 and 50,000 men. The sometimes extremely high information in the contemporary sources of 60,000 participants or even more do not correspond to modern research results and are not tenable from a logistical point of view. The historian Juliet Barker estimates the French combatants at just under 22,000. Anne Curry, on the other hand, assumes a troop strength of 12,000 men, of which at least two thirds were armed. She takes the view that the French did not manage to gather their troops in time. While most modern historians attribute the absence of some French aristocrats and their entourage exclusively to the contemporary inner-French power struggle, Anne Curry only allows this to apply to a few.

There are also good arguments for the numerical inferiority of the French. So the French contemporary sources are on the pro-English side and are interested in exaggerating the defeat. In addition, due to a five-day parallel march , which the French carried out more quickly by increasing their speed and leaving slower troops behind in order to get in the way of the English, the French troops were not gathered together. After all, the defensive line-up of the French and the knights dismounted in the center, who traditionally relied on their offensive power on horseback, speak against their numerical superiority. Hans Delbrück estimates the strength of the French at only 4,000–6,000 men.

The two armies differed in their social composition. On the French side, nobles fought with their respective entourage. This entourage also mostly belonged to the (lower) nobility. In the English army, the aristocrats who made up the armed forces played a minor role. The main armed forces of the English were the archers, who came from non-aristocratic classes and were hired directly by Henry V. Anne Curry sees this as a decisive advantage for the Anglo-Welsh side. On the French side, from their point of view, an army that was only loosely assembled and characterized by internal disputes was fighting with an unclear battle order. The Anglo-Welsh troops, on the other hand, had a clear structure of command and a stronger sense of community.

Course of the battle

Advance of the Anglo-Welsh army

At dawn the French and Anglo-Welsh armies assumed their respective order of battle. At that time, between them lay an open and almost flat piece of farmland about 900 to 1,000 meters long, which was lined with wood on both sides. It had been plowed just before the battle to sow winter wheat. On the French side, the distance between the two trees was around 1,100 meters.

Before the start of the battle, envoys from both armies negotiated one last time in the middle of the prospective battlefield in order to reach a peaceful agreement. Juliet Barker is convinced that the initiative came from Henry V because it was one of his duties as a Christian king to make further efforts to prevent bloodshed. Anne Curry, on the other hand, sees these negotiations as a delaying tactic on the part of the French, who wanted to gain time until further reinforcements arrived. The negotiations were unsuccessful. After that the two armies faced each other for three or four hours without any acts of war. According to the military doctrine of the time, whoever set his troops on the march first accepted a disadvantage. Two of the contemporary chroniclers of the battle report that during these hours of waiting, the French sat down in the front row, ate, drank and buried old arguments among themselves. After all, it was Henry V who ordered his troops to approach the French within about 250 to 300 meters. At this distance the arrows of the Anglo-Welsh archers could reach the French side. John Keegan suspects that it took the Anglo-Welsh army a good ten minutes to negotiate the approximately 600 meters of arable land that had been softened by rain. The advance period was a very critical moment for the British. The English archers had to pull out the stakes that had been driven into the ground for their protection and hammer them in further ahead. Had the French mounted soldiers attacked at that moment, they would have been largely defenseless.

Contemporary reports contradict one another as to why at this obvious moment there was no French mounted attack. The French sources agree that the mounted men were not in the places that the battle order provided for them at that moment. Gilles le Bouvier, one of the contemporary chroniclers of the battle, noted that nobody expected a movement on the English side at this moment and that many of the mounted had left their positions to warm up, to feed their horses, to water or to ride warm . It may not have been just indiscipline. Only stallions were used as battle horses , whose natural aggressiveness made it impossible to stand next to one another for several hours. Thanks to the element of surprise, the Anglo-Welsh army reached the narrowest point between the woods of Azincourt and Tramecourt. The width of the English position at this point should have been about 860 meters. The French mounted men could no longer ride around the English army in a pincer-like manner and attack from the sides because of the directly adjacent wood, but now had to attack frontally.

Attack of the French mounted soldiers

Immediately after the Anglo-Welsh army advanced, the archers opened the actual battle. It is not known how the commands between the various departments of the archers were synchronized. What is certain, however, is that the Anglo-Welsh archers largely fired their arrows at the same time. English archers were skilled at hitting a target with a high, parabolic trajectory, and this was the shooting technique used here. The primary aim of this hail of arrows was to provoke the French army to attack. The arrows themselves did not do much damage to the French armed because of their low top speed and the steep angle of impact. The padded cloth cloaks of the horses were pierced by the sharp tips of the arrows even at this distance, so that an injury to at least some of the horses on the French side is likely.

The French army responded to the arrow attack by attacking their mounted men. Instead of 1,000 (or - depending on the author - 800 to 1,200) mounted men, however, only about 420 French riders attacked the archers. The attack by the French cavalry remained ineffective not only because of the small number. Because of the heavy and soggy arable soil, the horses of the French cavalry did not reach their full attack speed, sometimes slipped and fell, so that the line of riders was pulled far apart. The reduced speed of the equestrian attack also exposed the horses to fire from the archers for longer. Warhorses were trained to rush against a target such as another rider or a foot soldier. However, even a trained horse would have shied away from an obstacle that it could not avoid or jump over.

It is therefore considered certain that the archers stood in front of their posts until the French cavalry approached the lance and the horses could no longer turn around in front of the posts. Some horsemen broke into the ranks of the Anglo-Welsh archers. It is known that three leaders of the French mounted men were killed in the process. The horses of Robert de Chalus, Poncon de la Tour and Guillaume de Saveuse had been brought down by the stakes, their riders fell between the Anglo-Welsh archers and were slain by them. Numerous other mounted leaders, however, survived. Contemporary chroniclers of the battle such as Gilles de Bouvier have taken the significantly lower death rate of mounted soldiers compared to the French armed men as an opportunity to accuse them of cowardly failure.

The attack by the French horsemen, which was supposed to put the Anglo-Welsh archers out of action, not only failed, but ultimately turned against the French army. Only some of the mounted and some of the stray horses escaped into the woods that bordered the battlefield. Most of the horses and French riders turned and galloped back. Some of the horses collided with the French vanguard, which had started their attack at the same time as the riders.

Attack by the French armed forces

The first detachment of the French foot troops - probably eight thousand men in eight tightly packed rows - began to march at the same time as the attack by the French mounted soldiers. According to John Keegan's estimates, they would have reached the line of the English foot troops in three to four minutes under normal circumstances. Several factors prevented this. Those of the foot troops who - as was already common practice at that time - did without a shield, were forced to lower their visor to protect their face from the arrows. However, this hindered breathing and significantly restricted the view. Because of the dense row, however, even if they recognized the horses galloping towards them early on, they were not able to open the rows quickly enough to let them through. Some of the men were trampled to the ground and the movement of those who dodged and fell halted the advance.

The heavy weight of the plate armor, to which a lance , sword, dagger and possibly mace were added, posed a relatively minor problem for the approaching French aristocrats. They had been used to fighting and each other in this armor and equipment since their youth move. Similar to the French mounted men, they were mainly hindered by the soft, heavy soil. Some of them sank up to their knees in the clay, which slowed the advance considerably and made it unusually strenuous for them. Those who fell in the front rows during the advance had little opportunity to get up because of the advancing rows behind them. The slowdown in French forward movement gave the Anglo-Welsh archers the opportunity to fire several volleys of arrows at the approaching people. At this point in time, this should have resulted in injuries and deaths among the French armed forces. The armor's weak points were the shoulders and the slits in the visor. The archers now shot their arrows flat so that they could penetrate armor plates at shorter distances.

A meeting of the armed

Several chroniclers report that the French armed men met the English front line in three pillars and that the fight was concentrated on the relatively short front line on which the Anglo-Welsh armed men and thus the Anglo-Welsh nobility stood. From the point of view of a French nobleman, it was neither honor nor ransom to fight against common footmen like archers. These were also still protected by the stakes rammed diagonally into the ground, which would have hindered an armed man in a fight against archery who were only lightly or not at all armed and therefore more mobile.

According to the reports of the chroniclers, the English withdrew "a lance's length" when they met the French. The priests behind the Anglo-Welsh line interpreted the retreat as the first indication of an English defeat and broke out in loud wailing. Although outnumbered, the Anglo-Welsh armed forces recovered and in turn attacked the French. The French armed men had shortened their lances. This made them easier to use in close combat . The English-Welsh armed men, on the other hand, had refrained from shortening the lances. This gave them an advantage when the two troops first met. Presumably, the thrusts of the English-Welsh armed men were aimed primarily at the abdomen and legs of the attacking French and aimed at bringing the armed men down.

John Keegan, Anne Curry and Juliet Barker unanimously argue that at that moment the numerical superiority of the French was detrimental to them. In order to fight effectively, a warrior needed space to dodge sideways or backwards from the blows of the enemy. The seven to eight hundred French who faced the English and Welsh directly did not have it, because behind them thousands of French armed men pushed forward. The English, on the other hand, were only staggered in four rows and were therefore superior to the French in direct duels. The French, who fell in the first minutes of the fight, further restricted the mobility of the rest of the French. Keegan believes that this was the determining factor that decided the Battle of Azincourt in favor of the English:

“If the French line had for the most part remained firmly on its feet, then their great numerical superiority would within a short time have pushed back the English. But if men ever went down […], those in the following row had to find out that they could only get within range of the English if they stepped over or on the body of the lying person. Assuming the pressure from behind would continue, they had no other choice; But this made them even more susceptible to a fall than those who had already been felled; because a person's body either provides an unstable fighting platform or it forms a highly effective obstacle for a man who tries to defend himself against a very wild attack from the front. "

A few, like the young Raoul d'Ailly , were lucky enough to be pulled out alive from the pile of the fallen during the battle . Most of the wounded and fallen French were crushed by the weight of their comrades in arms or suffocated in the mud. The chroniclers spoke of “dead people piled up against the wall” or “heaps as high as a man” of corpses. According to the analyzes of John Keegan, this is one of the exaggerations of medieval chroniclers. The dead were piled in the front line, but on the basis of studies of costly battles in the 20th century, it is known that the bodies of the fallen do not pile up to form walls. Even in the most competitive places, therefore, no more than two or three bodies lay on top of each other.

Intervention of the Anglo-Welsh archers

The chroniclers unanimously report that it was at this point in time that the Anglo-Welsh archers intervened directly in the battle. You should not have had any more arrows at this point. Archers usually had one or two quivers of 24 arrows that they could shoot ten seconds apart. It is therefore certain that they ran out of arrows half an hour after the first fighting between the armed men. They attacked with daggers, swords, battle axes and hammers , which they used to drive the stakes in. Since they would have been defeated in an open fight with an armed man, John Keegan assumes that their attacks were directed against the French who were on the edge of the fighting and were already fallen or wounded.

The side attack by the archers and the frontal attack by the Anglo-Welsh armed forces meant that most of the French front line was either already fled, dead, wounded or ready to surrender when the French second line attacked. The contemporary chroniclers report very little about this reinforcement on the French side. John Keegan suspects that the chroniclers remained silent about this reinforcement on the French side because the experiences of the first line were repeated and the reinforcement had no noticeable effect. Their attack was largely neutralized by the counter-movement of the fleeing people and robbed of its effectiveness by the numerous dead on the battlefield.

The fighting on the English side had initially not taken any prisoners. Only with increasing certainty of victory did the English refrain from killing the French high nobility, because their release promised a lot of ransom. A large part of the French high nobility was captured by English infantry. The Duke of Bourbon fell into the hands of Sir Ralph Fowne, one of Ralph Shirley's entourage; Jean II Le Maingre , Marshal of France , was imprisoned by William Wolfe, a simple esquire . Arthur de Richemont and the Duke of Orléans were wounded by archers pulled out from under the corpses of French armed men.

Killing the prisoners

Henry V could not be quite sure of his victory three hours after the start of the battle, as three incidents showed, which occurred in quick succession or in parallel: The Duke of Brabant , fighting on the French side, arrived late on the battlefield with a small entourage, but attacked immediately. However, his brave attack was in vain. He was overwhelmed and captured. The courageous example of the Duke had the Counts of Masle and Fauquemberghes, who belonged to the third French line, also attack with a small force. However, they were killed during the attack. Almost at the same time, screams and noise made the English conclude that the barely guarded baggage train behind the Anglo-Welsh troops was being attacked by the French. Henry V gave the order to kill all but the most important of the French captured. It is reported that Heinrich's subordinates refused to give the order to kill and that the English king finally dispatched 200 archers under the orders of a man in armor to carry out the order. It is no longer possible to reconstruct how many French prisoners were killed as a result of this order. After the battle, between 1,000 and 2,000 French prisoners accompanied the Anglo-Welsh army back to England, most of whom had been captured prior to the order. The chroniclers also report that the order was withdrawn after Henry V was certain that the French third line refrained from attack.

Juliet Barker names the order to kill Henry V as logical and points out that this order was not even criticized by contemporary French chroniclers. Heinrich's troops were physically and emotionally exhausted after the three hours of fighting. He had no information about the strength of the regrouping French troops and had to reckon with the fact that the French prisoners, who were only disarmed and guarded by a few Englishmen, would again take up arms. Anne Curry came to a similar conclusion as Juliet Barker after her source research, but she doubts that Heinrich V knew about the attack on the baggage train at this time. The historian Martin Clauss , on the other hand, takes the view that the English, on the orders of Heinrich V, broke the current legal conventions of their time, whose chivalric norms and rules demanded that prisoners be spared. In his view, contemporary English chronicles keep silent about this atrocity of war or only hint at it because they originated in the vicinity of the English royal court. Contemporary French sources focus on the misconduct of one's own side against the background of the power struggles within France. This is how Burgundian chroniclers see the responsibility for the attack on the English entourage with army commanders of the Armagnaks , who are thus also to blame for the death of the French prisoners.

John Keegan considers the number of prisoners killed to be low. He considers a mass execution, in which English archers successively slew French prisoners with axes or cut their throats with daggers, as impossible without the French aristocrats defending themselves against killing by foot troops, whom they despised as socially inferior. He believes that a scenario in which English armed men protested loudly that the prisoners who were so valuable to them because of the ransom payments were to be killed, that there was a quarrel between them and the firing squad, the prisoners from the battlefield, where weapons were more accessible to them, was much more likely Lying nearby, were led away and the archers killed individual French armed men on the sides during this withdrawal. There is, however, an eyewitness account that shows how the execution order may have been complied with: Ghillebert de Lannoy was wounded in the head and knee during the battle. He was found among the French corpses and captured and locked in a hut with ten to twelve other prisoners. When the order to kill came, this hut was set on fire. Ghillebert de Lannoy managed to escape from the burning hut. However, he was captured again shortly afterwards.

Dead and prisoners

The number of deaths on either side is unknown. On the English side there are at least 112 dead. The number is almost certainly incomplete and does not count those who died of their wounds after the battle. All contemporary sources emphasize the high number of victims on the part of the French, but the English chronicles in particular downplay their own number of victims. After the siege of Harfleur, the English dead had been precisely recorded, for with their death the king's obligation to pay wages ended. According to Azincourt, such a careful listing was omitted. Possibly the number of deaths was so small that it was of little importance to the crown if its captains collected wages for a few weeks for the fallen. Anne Curry does not think it is ruled out that Heinrich V deliberately downplayed the number of his own deaths, as it was foreseeable that further campaigns in France would soon follow.

What is striking is the very large difference between the nobility on the Anglo-Welsh and French sides, who died in battle. On the English side, only Edward of Norwich, 2nd Duke of York , and the only 21-year-old Michael de la Pole, 3rd Earl of Suffolk , fell from the nobility . The fatalities on the French side include Johann I , Duke of Alençon ; Anton , Duke of Brabant and Limburg ; Edward III. , Duke of Bar ; Jean de Montaigu , Archbishop of Sens ; Charles I. d'Albret , Count of Dreux ; Frederick I , Count of Vaudémont ; Johann VI. , Earl of Roucy and Braine ; Philip of Burgundy , Count of Nevers and Rethel ; William IV, Count of Tancarville ; Jean IV. De Bueil ; 19-year-old Charles de Montaigu, Vidame de Laon ; Jean de Craon, Vice Count of Châteaudun ; Pierre d'Orgemont, Lord of Chantilly and Hugues III. d'Amboise, father of Pierre d'Amboise .

Prisoners who survived the warrant included Charles , Duke of Orléans ; John I , Duke of Bourbon ; Georges de La Trémoille , Count of Guînes ; Jean II. Le Maingre , Marshal of France ; Arthur de Richemont , later Duke of Brittany ; Louis de Bourbon, Comte de Vendôme and Charles d'Artois , the Count of Eu . For Henry V these prisoners were valuable not only because of the high demands for ransom. For many years, their captivity in England symbolized the devastating defeat suffered by the French army at the Battle of Azincourt. How many more French prisoners accompanied the Anglo-Welsh army from Calais back to England is not certain. Contemporary sources give between 700 and 2,200. What is certain is that a number of prisoners were already able to provide their ransom in Calais and therefore never left French soil. According to her source studies, Anne Curry could only prove a total of 282 prisoners who spent part of their captivity in England.

Effect of defeat

France was so severely defeated militarily that the English regent Henry V was able to enforce his war aims in the following years, occupied Caen and finally, five years later, forced the Treaty of Troyes on the French crown , through which he married the French princess Catherine of Valois and himself to the successor of the French King Charles VI. made.

The extent of France's defeat also led to a realignment of Burgundian politics, which came to fruition in the Treaty of Troyes in 1420. The King of England was recognized by the Burgundians as King of France in order to work towards the formation of an independent empire.

swell

The Battle of Azincourt is the best and most extensively documented battle of the Middle Ages. Many of the original documents such as master roles , tax documents, letters and even the battle plan drawn up by the French about two weeks before the event have been preserved over the centuries and are scattered in numerous libraries . In addition, many contemporary chroniclers on the English and French sides reported on this battle.

The closest source is the Gesta Henrici Quinti , the report of Henry V's deeds, which was written by an English eyewitness whose name was not known, probably at the beginning of 1417. The Vita Henrici Quinti by Tito Livio Frulovisi from 1438 was written at the court of the Duke of Gloucester and also describes the fighting from an English perspective.

The French chroniclers from the mid-15th century include Pierre de Fénin , Enguerrand de Monstrelet and Jean de Wavrin .

The Battle of Azincourt as a Patriotic British Myth

The memory of the battle has become a national myth in Britain . In 1944, in the middle of World War II , Shakespeare's drama Heinrich V (with Olivier in the lead role ) was filmed in Great Britain at great expense and under the direction of Laurence Olivier , in order to support the British in the fight against the Germans.

Even after more than 600 years, the battle is still deeply anchored in the collective consciousness of the British as the greatest British victory in (military) history - not least because it was a victory against the “ archenemy ”, the French. Alongside the battles of Trafalgar (1805 against Villeneuve ) and Waterloo (1815 against Napoléon ) , Azincourt appears at more or less regular intervals in the British rainbow press when it comes to the current (in these cases always tense) relationship between the kingdom and its neighbors France goes. In the debate on February 1, 2017 about Brexit , the Conservative MP Jacob Rees-Mogg in the British House of Commons said that the day of the EU referendum would go down “as one of the most important days” in British history and in future with the battles of Azincourt and Waterloo are equated.

For several hundred years, the English interpretation of events had prevailed: Henry V and his men were faced with a huge opposing force. Until a few years ago, a ratio of 4: 1 in favor of the French was still believed. However, recent research by Anne Curry suggests that the numerical preponderance of the French may have been much less. After a detailed study of the sources, she comes to the conclusion that the French only led a few thousand more men into battle. The exact balance of power remains a matter of dispute.

The British zoologist and behavioral scientist Desmond Morris explains in the first episode of his six-part BBC documentary series Das Tier Mensch ( The Human Animal ) from 1994: “In Britain, the main insult is a two-finger gesture, which dates back to the Battle of Agincourt. It's a gesture that foreigners sometimes confuse with the 'V for Victory' sign, but that's performed with the hand the other way around. "Translated:" In Great Britain the biggest insult is a two-finger gesture [consisting of an outstretched means - and forefinger, both slightly spread apart], which can be dated back to the Battle of Azincourt. It is a gesture that foreigners occasionally confuse with the 'V for Victory' sign, which is shown with the hand the other way around ”(i.e. with the back of the hand facing the actor). The V-symbol represented in this way probably symbolizes the Latin dynastic addition in the name of the victorious English king and commander Heinrich V.

Literary and cinematic processing

- The battle is thematized in William Shakespeare's Henry V. This piece has been filmed three times under the original title. 1944 by and with Laurence Olivier and 1989 by and with Kenneth Branagh . 2012, available in English only series published The Hollow Crown , consisting of Shakespeare's works , Richard II , Henry IV Pt1 & Pt2 and Henry V .

- In the novel, the character of the victory of Bernard Cornwell the battle from the perspective of English archers in detail. In 2013, the start of the shooting of a film adaptation directed by Michael Mann was planned.

- In the novel The guardians of the Rose by Rebecca Gablé the battle occupies a small part of the plot. The representation takes place here from the point of view of a young English nobleman.

- In the prologue of the science fiction novel The Resistance by David Weber , the battle is portrayed from the perspective of a fictitious herbivorous alien race.

- The film The King (2019) focuses on the reign of Henry V and the Battle of Azincourt.

literature

- Johann Baier: The battle at Agincourt. Hörnig, Ludwigshafen 2006, ISBN 3-938921-01-3 .

- Juliet Barker : Agincourt. The King - The Campaign - The Battle. Abacus, London 2006, ISBN 0-349-11918-X .

- Matthew Bennett: The Battle. In: Anne Curry (ed.): Agincourt 1415. Henry V., Sir Thomas Erpingham and the Triumph of the English archers. Tempus, Stroud 2000, ISBN 0-7524-1780-0 .

- Martin Clauss: The prisoners of Agincourt. In: Sönke Neitzel , Daniel Hohrath (ed.): War atrocities. The dissolution of violence in armed conflicts from the Middle Ages to the 20th century. Schöningh, Paderborn 2008, ISBN 978-3-506-76375-4 .

- Anne Curry: The Battle of Agincourt. Sources and Interpretations. Boydell, Woodbridge 2000, ISBN 0-85115-802-1 .

- Anne Curry: Agincourt. A New History. Tempus, Stroud 2005, ISBN 0-7524-3813-1 .

- John Keegan : The Face of War. Econ, Düsseldorf 1978, ISBN 3-430-15290-9 .

- Paul Hitchin: The bowman and the bow. In: Anne Curry (Ed.): Agincourt, 1415. Henry V, Sir Thomas Erpingham and the triumph of the English archers. Tempus, Stroud 2000, ISBN 0-7524-1780-0 , pp. 37-52.

- Hagen Seehase, Ralf Krekeler: The feathered death. The history of the English longbow in the wars of the Middle Ages. Hörnig, Ludwigshafen 2001, ISBN 3-9805877-6-2 .

Web links

- Beck, Stephen: The Battle of Agincourt ( November 9, 2007 memento in the Internet Archive )

- The Battle of Azincourt

- Hans-Henning Kortüm: The battle of Azincourt: The work of God. (Overview - THEN - history online)

Remarks

- ↑ Hans Delbrück: History of the art of war. The middle age. Nikol 2000, pp. 533-543.

- ↑ John Keegan: The Face of War. Düsseldorf 1978, p. 89f. The British historian Anne Curry walks in her Agincourt. A New History (2005) goes into great detail on each individual event on the respective sources.

- ↑ See for example Curry (2005).

- ↑ a b c d e f John Keegan: The face of war. Düsseldorf 1978, pp. 92-94.

- ↑ See for example Wolfgang Hebold: Siege und Deflagen - Military decisions from Troy to Yom Kippur , Gerstenberg Verlag, Hildesheim 2002, ISBN 3-8067-2527-6 , p. 100.

- ↑ See, for example, Seehase and Krekeler, p. 126.

- ↑ See, for example, John Keegan: The Face of War. Düsseldorf 1978, p. 95.

- ↑ Baier, p. 39.

- ↑ a b Seehase and Krekeler, p. 85.

- ↑ a b Curry (2005), p. 253.

- ↑ Hitchin, p. 44. According to his own account, Paul Hitchin achieved 17 arrows per minute after 15 years of training.

- ↑ a b c Seehase and Krekeler, p. 47f.

- ↑ Hitchin, p. 46.

- ↑ Seehase and Krekeler, p. 199; Hitchin, p. 46. The bow used had a draw weight of 165 pounds.

- ↑ Barker, p. 273

- ↑ Baier, p. 51; Curry (2005), p. 218.

- ↑ Curry (2005), pp. 218f.

- ↑ Barker, p. 272.

- ↑ Barker, p. 307.

- ↑ Barker, p. 277.

- ↑ a b Keegan, p. 100.

- ↑ Barker, p. 276.

- ↑ Curry (2005), pp. 230-231.

- ↑ a b c Keegan, p. 103.

- ↑ Anne Curry comes to the same conclusion in her study, which is almost three decades younger, see Curry (2005), pp. 231–233.

- ↑ a b Curry (2005), p. 228.

- ↑ Curry (2005), pp. 228-229.

- ^ Anne Curry: Agincourt. A New History. Stroud 2005, pp. 225f.

- ↑ Barker, pp. 274-275.

- ↑ Curry (2005), p. 221.

- ↑ Hans Delbrück: History of the art of war. The middle age. Nikol 2000, pp. 533-543.

- ^ Curry (2005), p. 222.

- ↑ Keegan, pp. 94 and 100; Curry (2005), p. 240f.

- ↑ Barker, p. 284.

- ^ Curry (2005), p. 238.

- ↑ Keegan, pp. 94 and 101; Baier, p. 71.

- ^ Keegan, p. 101.

- ↑ Barker, pp. 285-290; Baier, p. 72.

- ↑ Barker, p. 291.

- ↑ a b Baier, p. 87.

- ^ Keegan, p. 104.

- ↑ Bennett, p. 33.

- ↑ a b Keegan, pp. 105-106.

- ↑ a b c d Bennett, p. 35.

- ↑ Barker, p. 292.

- ↑ Barker, pp. 292-294.

- ↑ Baier, p. 90.

- ^ Keegan, p. 109.

- ↑ Barker, p. 294.

- ↑ Barker, p. 296.

- ↑ Curry (2005), p. 250.

- ↑ Barker, p. 297.

- ^ Keegan, p. 111.

- ↑ Military historians are able to estimate the impact of a shy horse that meets a dense line of people very well on the basis of a random film recording. The film was shot in 1968 when a shy police horse galloped into a tightly packed chain of police officers. The movement of those evading and falling also affected police officers who were very far away from the place of the collision. See Keegan, p. 111.

- ↑ a b Barker, p. 298.

- ↑ Curry, p. 254.

- ↑ Curry (2005), p. 244.

- ↑ Baier, p. 104.

- ↑ Barker, p. 299.

- ↑ a b Curry (2005), p. 255.

- ↑ Keegan, pp. 115-116.

- ↑ a b Barker, p. 300.

- ^ Keegan, p. 116.

- ↑ quoted from Keegan, p. 122.

- ^ Keegan, p. 123.

- ^ Keegan, p. 117.

- ↑ a b Keegan, p. 122.

- ↑ a b c Barker, pp. 302, 305.

- ^ Bennett, p. 36.

- ↑ Keegan, pp. 124f. and Barker, p. 307.

- ^ Keegan, p. 126.

- ↑ Barker, pp. 303-304.

- ^ Keegan, pp. 127, 129.

- ↑ Curry (2005), pp. 262, 294-295.

- ^ Clauss, p. 117.

- ^ Clauss, pp. 109-111.

- ↑ a b Clauss, p. 116.

- ↑ a b c Keegan, pp. 128-129.

- ↑ Barker, pp. 304-305.

- ↑ Barker, p. 320.

- ↑ a b Curry (2005), p. 281.

- ↑ Barker, p. 314

- ↑ Curry (2005), p. 285.

- ↑ Curry (2005), p. 286.

- ↑ Curry (2005), p. 289.

- ^ Curry (2005), p. 290.

- ↑ Clauss, p. 109.

- ↑ Die Zeit, zeitonline from February 1, 2017: [1]

- ^ Professor Anne Curry, Research Interests website at the University of Southampton, accessed October 25, 2011.

- ↑ Michael Mann's Agincourt Is Getting A Rewrite (Cinemablend message from May 2, 2013, accessed June 18, 2013)