UK withdrawal from the EU

The UK's exit from the EU , often referred to as Brexit , took place on January 31, 2020 and is governed by the Withdrawal Agreement signed on January 24, 2020. In the transition phase agreed there until December 31, 2020, the long-term relations between the United Kingdom (UK) and the European Union (EU) were renegotiated until December 24, 2020 . As of January 1, 2021, the United Kingdom is no longer part of the EU internal market and the customs union .

The exit process was initiated by the EU membership referendum on June 23, 2016 (usually called the Brexit referendum), in which 51.89% of the participants voted in favor of leaving the EU. On March 29, 2017, Prime Minister Theresa May initiated the legally effective withdrawal from the EU and from EURATOM in accordance with Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union by means of a written notification to the European Council Was extended three times in 2019.

In January 2017, May presented a twelve-point plan for a Brexit without EU partial membership or associated membership in a keynote address; the UK should therefore leave the European internal market, the customs union and the jurisdiction of the European Court of Justice . On November 14, 2018, the EU and the UK government agreed on a corresponding withdrawal agreement.

The vote on the exit agreement , scheduled for December 11, 2018 in the British House of Commons , was postponed due to internal political resistance, in particular the so-called " backstop " clause, which was supposed to prevent a hard border between Ireland and the United Kingdom , and further renegotiations took place . In three votes between January and March 2019, the House of Commons voted against the agreement with a large majority. To prevent uncontrolled discharge on 29 March 2019, the agreed European Council and the British government of the exit date twice on a shift by 31 October 2019. Therefore, the UK had on 23 May at the European elections to participate in the Brexit party, founded in 2019, immediately received 30.5% of the votes and won the election with 29 seats in the EU Parliament .

In July 2019 Theresa May resigned from office and Boris Johnson was her successor. The House of Commons passed a law at the beginning of September that obliged the Prime Minister to apply to the EU for a further extension if no exit agreement had been ratified by October 19. On September 10th, Johnson adjourned Parliament for an unusually long period of time with a prorogation that was declared unlawful by the Supreme Court on September 24th . On October 17th, the British government and the EU agreed on a renegotiated agreement that no longer provides for a backstop. Since the House of Commons postponed the vote on October 19, Johnson was forced to request another postponement of the exit date to January 31, 2020. The European Council granted the request on October 28th. Thereupon the lower house decided an early election for December 12th. In this case, the Conservative Party received an absolute majority of the lower house seats. In January 2020 the British Parliament and the EU Parliament approved the Brexit Agreement, with which the UK left the European Union and EURATOM on January 31, 2020 at 11 p.m. UTC (24 p.m. CET ), but part of the until the end of 2020 EU internal market and the customs union remained.

Brexit is predicted to hit the UK economy in particular; Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, this has already been in a recession since March 2020 . It is also expected to have a significant impact on the EU, especially Germany and other EU countries closely linked to the UK.

With the trade and cooperation agreement between the European Union and the United Kingdom signed on December 30, 2020 and provisionally entered into force on January 1, 2021 , the legal aspects of leaving the EU have now been clarified for the time being.

Term Brexit

As an abbreviation for the emergence of the United Kingdom from the European Union is the world's art and portmanteau United Kingdom and Gibraltar European Union membership referendum established - a fusion of British and exit ( German exit ). The Duden classifies the term Brexit as political jargon . After appearance of the word Grexit for the possible exit of Greece from the euro - currency area of the 21st century in the first decade a number of similar terms was formed, primarily through print media .

The first use of the term Brexit can be traced back to May 15, 2012. The made-up word Brixit appeared as a variation in June 2012 .

Brexit advocates are occasionally called Brexiteers or Leavers , Brexit opponents Remainers and pejorative Remoaners ( suitcase word from remainer ' Verbleiber ' and moan 'whine') or Bremoaners .

timeline

Trigger 2011

According to Cameron himself (in the BBC documentary The Cameron Years, broadcast in 2019 ), an EU summit on December 8, 2011 ultimately led him to promise a Brexit referendum. On December 8th, Angela Merkel and Nicolas Sarkozy called for an amendment to the Lisbon Treaty in order to stabilize the euro. Cameron only wanted to agree to this if the envisaged treaty change also took British interests into account, which Merkel and Sarkozy refused. Cameron then vetoed an amendment to the Lisbon Treaty. Nonetheless, a majority of EU countries signed a sub-contract to stabilize the euro. In Cameron's words, ignoring a veto meant that "the UK's situation in the EU was actually profoundly unstable". From that experience, Cameron concluded over Christmas 2011 that “we had indeed to seek to anchor, secure and order the instability of Britain's position within the EU, and I made the decision that it was time to move towards one Move referendums. "

2016

- February 20: British Prime Minister David Cameron announces the timing of the referendum on leaving the EU.

- April 13: An electoral commission recognizes two associations as campaign organizations, namely Vote Leave and Britain Stronger in Europe .

- June 23: In the referendum on the United Kingdom's exit from the EU, just under 52% of voters decide to leave.

- June 24: Prime Minister Cameron announces his resignation in October 2016.

- July 13: The original Brexit opponent Theresa May is appointed as the new Prime Minister. Brexit advocate David Davis becomes Minister for Leaving the European Union .

2017

- February 1: The House of Commons authorizes the British government by law to submit an application to leave the EU.

- March 1: The British House of Lords proposes an amendment to the Brexit Act.

- March 13: The House of Commons denied the amendment to the Brexit Act. The House of Lords accepts the original Brexit law.

- March 29: The UK's official application to withdraw from the EU under Article 50. The UK and the EU have until March 29, 2019 to negotiate the terms of the withdrawal.

- April 18: Early election for the lower house is announced.

- June 8th: The House of Commons is re-elected.

- December 15: The Council of the European Union notes that the necessary progress has been made on the issues of the exit amount , citizens abroad and the Irish border , and decides to enter the second round of negotiations.

2018

- June 20: The Withdrawal Act comes into force. It ensures that after the exit, the European rules become British rules so that the UK can amend them.

- July 9: Dominic Raab becomes Minister for Leaving the European Union .

- November 13: The European Commission publishes an emergency plan in the event of an exit without an agreement.

- November 14: The European Commission and the British government present the draft withdrawal agreement.

- November 16: Stephen Barclay becomes Minister for Leaving the European Union .

- November 25: The European Council approves the text of the Withdrawal Agreement as the outcome of the negotiations, which will first be submitted to the UK Parliament and, once it has approved, the European Parliament for a vote.

- December 10: The British government cancels the vote on the agreement in the House of Commons planned for December 11, as May fears defeat. She subsequently tried in vain to obtain further concessions from the EU.

2019

- January 15: The House of Commons decides against the withdrawal agreement (432: 202 votes).

- March 12: The House of Commons decides again against the exit agreement (391: 242 votes).

- March 13: The House of Commons rejects the UK's exit from the EU without an agreement (321: 278 votes) after a previously adopted amendment (312: 308 votes) removed the time limit from the main motion.

- March 14: The House of Commons rejects a second referendum on remaining in the EU (85: 334 votes). Furthermore, the House of Commons refuses to allow parliament to determine the parliamentary agenda instead of the government (312 votes to 314). A motion by the government to be mandated to negotiate with the EU to postpone the exit date by at least three months is accepted (412: 202 votes).

- 20./21. March: Prime Minister May asks the European Union to postpone Brexit until June 30, 2019 and agrees with the European Council on a postponement until at least April 12.

- March 29: The House of Commons decides against the adoption of the withdrawal modalities of the Withdrawal Agreement (344: 286 votes).

- April 5: Prime Minister May again asks the European Union to postpone Brexit until June 30, 2019.

- April 10: The EU-27 summit with Prime Minister May in Brussels approves the proposal to give the UK until October 31, 2019 to accept the negotiated treaty. Otherwise, the UK will leave the EU in an unregulated manner on October 31.

- April 11: The United Kingdom announces that it will take part in the European Parliament elections on May 26, 2019.

- May 24th: Prime Minister May announces her resignation as head of the Conservative Party on June 7th.

- July 24: Boris Johnson becomes new Prime Minister and names his new cabinet . He promises Brexit for October 31st - under all circumstances (“do or die”).

- August 28: Prime Minister Johnson announces an interruption of the current session of Parliament (so-called prorogation ) from September 10th to October 10th.

- September 3: The British government loses its majority in the lower house during the current parliamentary session due to the faction change of Tory MP Phillip Lee to the pro-European liberals .

- September 9: Parliament passed a law with 311: 302 votes, which obliges the British government to request the EU to postpone the exit beyond October 31, provided that there is no exit agreement with the EU by October 19 is adopted.

- September 9: At the end of the day, the current session of Parliament is adjourned. The next scheduled day of the meeting is October 14th.

- September 24: The UK Supreme Court declares the suspension of the session of Parliament unconstitutional and therefore null and void . John Bercow, Speaker of the House of Commons, then announced that Parliament would resume its work on September 25th.

- October 17: The European Council (all heads of government including the United Kingdom) agrees on changes to the current Withdrawal Agreement from November 2018. This now provides, among other things, instead of the backstop, a regulation is proposed in which goods destined for the EU are already cleared and checked in Great Britain .

- October 19: The House of Commons postponed the vote on the new agreement, forcing Johnson to request the European Council to postpone the Brexit date again. Johnson sends a request for extension to Donald Tusk and another letter asking that the extension be refused.

- October 21: The UK government publishes draft Brexit law.

- October 22: The House of Commons votes for a second reading on the Brexit Act (329: 299 votes). However, the House of Commons voted against the legislative timetable proposed by the government (322: 308 votes).

- October 28: The European Council agrees to postpone the withdrawal date to January 31, 2020, with the option of an earlier withdrawal in the event that the Withdrawal Treaty is ratified earlier. The formal decision is available the next day.

- October 29th: The House of Commons resolves a new election for December 12th with 438: 20 votes.

- December 12: In the British House of Commons election , Prime Minister Johnson's Conservative Party wins an absolute majority of the seats.

- December 20: The House of Commons adopts the legislative proposal to leave the EU with 353: 243 votes. All 352 Conservative Party MPs and Labor MP Emma Lewell-Buck are voting in favor of the bill.

2020

- January 22nd: The British exit law proposed by Boris Johnson clears the final hurdle in the British Parliament with approval in the House of Lords . The House of Lords had previously tried to introduce several changes, but these were rejected by the House of Commons. With the Royal Assent the next day, the European Union (Withdrawal Agreement) Act 2020 becomes legally binding.

- January 24th: The exit agreement between the EU and the United Kingdom is signed first in Brussels by Ursula von der Leyen (President of the European Commission) and Charles Michel (President of the European Council), then by Prime Minister Boris Johnson at his official seat in London.

- January 29th: The EU Parliament ratified the Brexit agreement with 621: 49 votes and passed the resigning member by singing Auld Lang Syne .

- January 31: The Withdrawal Agreement will take effect at 23:00 UTC (24:00 CET). The UK is now considered a third country for the EU .

- October: The House of Lords ( House of Lords ) has rejected the controversial Single Market Act ( Internal Market Bill ab) with which the Johnson government wants to overturn the applicable United Kingdom and Gibraltar European Union membership referendum deal.

- November 7: Ursula von der Leyen and Johnson negotiate a post-Brexit trade agreement.

- November 9: The British House of Lords again rejects the controversial Single Market Act with 433 votes to 165.

- December 24th: An agreement in principle on a trade and cooperation agreement was reached. The governments of all EU member states and, in some cases, their parliaments, the European and British parliaments have yet to approve the agreement.

- December 30: EU Commission head Ursula von der Leyen and Council President Charles Michel sign the trade and cooperation agreement. The British House of Commons also voted for the agreement. The state parliaments of Scotland and Northern Ireland voted against the agreement. The state parliament of Wales voted in favor of the agreement. These decisions by the state parliaments were only symbolic.

- December 31: Queen Elizabeth II enacts the law applying the agreement with the EU. The governments of Great Britain and Spain decide that the British overseas territory Gibraltar will join the Schengen area .

2021

- January 1: The transition phase, which has been in effect since February 1, 2020, ends. The UK has left the EU internal market and customs union . The trade and cooperation agreement is provisionally applied. Gibraltar joins the Schengen area .

- first quarter of 2021: the volume of trade between Great Britain and the EU countries is 23.1 percent lower than in the first quarter of 2018 (which is considered to be the last stable trading period before Brexit). Trade with non-European countries fell by 0.8 percent in the same period.

- April 27: The EU Parliament approves the agreement.

- May 19: Talks between the UK and US governments on trade agreements stall.

- July 9, 2021: according to the new EU budget report 2020, the amount of the BREXIT exit bill is estimated at 47.5 billion euros. Britain thinks it should be £ 35 to £ 39 billion (€ 41 to 45.6 billion).

- Mid-September 2021: The Johnson II government postpones the controls planned from January 1, 2022 on goods imported from EU countries to Great Britain. British Brexit representative David Frost says the COVID-19 pandemic has had more long-term effects on companies than suspected six months earlier. The reasons for the postponement appear to be that the fresh food trade is suffering, the lack of truck drivers and that transport costs have increased. The Northern Ireland question is also worsening.

EU membership referendum 2016

background

Conservative David Cameron has served as moderately Eurosceptic prime minister since the 2010 general election . On January 23, 2013, he announced that if he was re-elected in May 2015 , he would have a referendum held in 2017 at the latest on whether the United Kingdom would remain a member of the EU . Before doing this, he wanted to negotiate with the European partners in order to reform the EU, particularly with regard to immigration and state sovereignty. After Cameron's announcements, the opinion of the EU increased in the polls until around mid-2015.

Cameron came under pressure due to the success of the UK Independence Party (UKIP), which demanded to leave the EU and which mainly drew its supporters from the Conservative Party's electorate. In the 2014 European elections , UKIP became the strongest force in the United Kingdom for the first time with 27.5%. In the general election in 2015 , it won almost four million votes (12.6%), but due to the British electoral system this resulted in only one of 650 lower house seats. The Conservative Party won an absolute majority of the seats.

The EU referendum bill, introduced by Cameron after the general election, was passed in December 2015.

Reform negotiations with the EU

The final phase of negotiations between the UK and the EU began at the end of January 2016. An agreement was reached at the final summit on February 18 and 19 in Brussels. The central reform demand to limit immigration was resolved in such a way that every EU country could apply for an “immigration emergency”; if approved by the EU Commission, the EU country concerned may pay reduced social benefits to newly arriving EU foreigners for four years. On February 20, Cameron announced June 23, 2016 as the date for the referendum in London.

Discussion and polls before the referendum

For the opponents of British EU membership, the reforms did not go far enough. On February 21, 2016, London's former Mayor Boris Johnson (Conservative Party) announced that he would join the campaign to leave the EU after making a strong case for the EU two days earlier. On his campaign bus he spread the controversial claim that the UK was transferring £ 350 million a week to the EU that would be better invested in the UK health service. In fact, the estimated total amount being transferred was £ 248 million a week. The representatives of the Remain campaign (Prime Minister Cameron and his Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne ) pointed out the importance of the EU single market for the British economy.

Immigration has become a major issue in the political dispute. Brexit advocates argued that the UK must regain control of its borders in order to curb immigration. Johnson and his colleagues stressed that immigration must be brought under control along the lines of the Australian model . The immigration compromise with the EU, on the other hand, was hardly used as an argument by the Remain campaign.

The British businessman Arron Banks supported the British independence party UKIP under its chairman Nigel Farage and the Brexit campaign Leave.EU, which he co-founded, with a total of twelve million pounds, the highest known political donation in the United Kingdom to date.

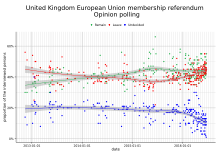

In most of the polls since mid-2014, the majority of voters voted for their country to remain in the EU. In the last few months before the referendum on June 23, 2016, the camps of Brexit supporters and Brexit opponents were almost equally strong in surveys. Since October 2015, the Brexit opponents have always been ahead by a few percentage points, only on May 12, 2016 and between June 12 and June 17, 2016 did the Brexit supporters lead by a narrow majority.

After the murder of Labor MP Jo Cox by a fanatical nationalist on June 16, 2016, a week before the referendum, political sentiment seemed to be turning against Brexit supporters. On the day before the referendum, the bookmakers at the betting shops estimated the likelihood of a Brexit at around 25%. The outcome of the referendum on June 23 came as a surprise to many.

Decision to leave

In the EU membership referendum on June 23, 2016 , the turnout was 72.2%. 51.89% of the electorate voted for the UK to leave the EU and 48.11% to stay. In EU-friendly Scotland and among the EU-friendly younger population, voter turnout was above average. The referendum was a purely consultative referendum and was neither binding on the government nor on parliament.

Political developments after the referendum

Resignations from Cameron, Hill, Farage

After the result of the referendum was announced, David Cameron announced on June 24, 2016 that he would step down by October 2016. He will explain the decision of the British people to the European Council on June 28, 2016, but leave the exit request and the exit negotiations to his successor.

The European Commissioner for Financial Stability, Financial Services and Capital Markets Union Lord Jonathan Hill announced his resignation on June 25th.

Nigel Farage resigned as UKIP party leader on July 4, 2016 . He stated that with the UK leaving, he had achieved his political goal. However, he will occasionally comment on the exit negotiations in the EU Parliament.

Power struggle in the Labor Party

The leader of the Labor Party , Jeremy Corbyn , was accused by party members of having only half-heartedly campaigned for the "Remain" campaign. For example, on June 11, 2016, he stated that his approval of the EU was 70% or slightly higher. The Labor MPs distrusted him on June 28th by 172 votes to 40, but only one party congress could decide on the replacement. Several members of the shadow cabinet resigned. On September 24, the Labor party base confirmed Corbyn as party leader with a share of the vote of almost 62% and a turnout of almost 78%.

After Corbyn had previously taken the line that one had to accept the referendum of the citizens on Brexit, he showed himself to be open to a new vote on Brexit at a party congress in September 2018, since he "had been elected as chairman for more internal parties Implementing democracy in Labor ”. In this respect, he wants to "bow to the party's decisions" in a vote for a second Brexit referendum. The majority of the delegates voted for a second referendum on Brexit.

Theresa May as the new Prime Minister

After the announcement of David Cameron's resignation, the party began applying for his successor as party chairman and prime minister. In the selection process, the promising candidates Boris Johnson, Michael Gove and Andrea Leadsom were eliminated, and Theresa May became party leader on July 11th.

On July 13, Queen Elizabeth II appointed Theresa May Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. May filled 15 of 18 ministerial posts and included both Brexit supporters and previous Brexit opponents in her cabinet . As prominent EU skeptics, Boris Johnson became Foreign Minister, David Davis Minister for Leaving the European Union and Liam Fox Minister for International Trade. On July 20, May announced to EU Council President Donald Tusk that the United Kingdom would waive its regular EU Council Presidency in the second half of 2017.

Reactions in Scotland

The Scottish First Minister Nicola Sturgeon ( Scottish National Party , SNP) said after the announcement of the result that a new referendum in Scotland on the whereabouts in the UK was "very likely". The result achieved in Scotland of around 60% per EU stay shows that the Scottish people see their future as part of the European Union.

On June 25, 2016, the Scottish Government began preparatory work for a possible second independence referendum. However, votes on Scottish independence are subject to UK legislature. The legality of a unilateral declaration of independence for Scotland was already controversial in the 2014 referendum . At that time, Parliament in London authorized the Scottish government to hold such a referendum as an exception.

On October 20, 2016, the Scottish Government published a bill for a second independence referendum; on March 13, 2017, Nicola Sturgeon announced a bill for a second independence referendum in the Scottish Parliament. On March 28, 2017, the Scottish Parliament authorized Nicola Sturgeon to request a new referendum in London, which it postponed after the SNP had lost 21 of its 56 seats in the early election to the House of Commons , and polls in Scotland regularly had a majority against one provided second independence referendum.

Reactions in the EU

The President of the European Commission Jean-Claude Juncker thanked David Cameron on June 28th for European merits and attacked the present European Parliamentarian Nigel Farage, a prominent representative of the British “Leave” campaign, with the question: “Why are you here? ”At the meeting the following day, the United Kingdom was absent; the Scottish Prime Minister made a courtesy call. It was adjourned until September without any concrete resolution.

Although Juncker, the President of the European Parliament Martin Schulz and the German Federal Minister of Finance Wolfgang Schäuble had spoken out in favor of deeper European integration , the referendum result initially strengthened the opponents of closer cooperation. Overlooking the referendum protested Jeroen Dijsselbloem , President of the Euro Group , before "new bold steps for further integration."

On the sidelines of the first EU conference without the UK on September 17, 2016 in Bratislava, Slovak Prime Minister Robert Fico threatened to veto any agreement between the EU and the UK, if not all EU citizens who emigrated there as citizens of equal value be acknowledged.

Juncker and the French President François Hollande advocated “toughness” in the Brexit negotiations in October 2016, there had to be a “threat, a risk, a price” to deter imitators in the remaining EU and thus “prevent the end of the EU”. Malta's Prime Minister Joseph Muscat said on October 5, 2016 that the 27 remaining EU countries would form a "united front" and that the United Kingdom should expect to be treated in the same way as Greece .

Five days after the referendum, she stated Angela Merkel in the German Bundestag behind the EU negotiating position: the United Kingdom could only remain in the single market, if it is the movement of persons accepted for EU citizens. It affirmed the connection between the free movement of goods, capital, services and people. The CDU foreign expert Norbert Röttgen promoted a new kind of economic partnership between the European Union and the United Kingdom after Brexit.

Markus Kerber , General Manager of the Federation of German Industries (BDI), spoke out against "punitive actions". In contrast, Angela Merkel pointed out in a speech to the BDI that defending the free movement of workers in the EU has priority over German industrial interests. In mid-November 2016, she hinted at a compromise on the immigration issue in the Brexit negotiations, according to which EU states would have to protect their social systems. In October, Labor Minister Andrea Nahles unilaterally made it difficult for EU foreigners to immigrate to the German social system, analogous to the failed EU immigration compromise with David Cameron.

General election 2017

On April 18, 2017, Prime Minister May announced the early election of the House of Commons for June 8, 2017 in order to overcome internal differences in parliament before the Brexit negotiations. Despite the conservatives' clear lead at times in the polls, the election resulted in a hung parliament in which no party received an absolute majority of the seats, with UKIP and the SNP losing votes. The Conservatives lost seats despite strong votes, so May formed a minority government supported by the Northern Irish Democratic Unionist Party ( confidence-and-supply agreement ), but without entering into a formal coalition.

Backlash after the referendum

Survey

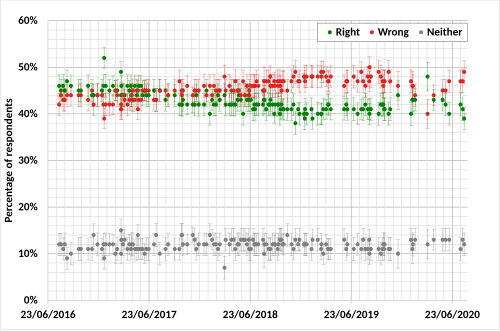

In an opinion poll on October 21, 2019, the question of "Do you believe in retrospect that it was right or wrong that the British voted for Brexit?" Answered 41% with "right" and 47% with " not correct"; on August 2, 2016 the result was: 46% “right” and 42% “wrong”.

The surveys on possible voting behavior in a second referendum between January 2018 and October 2019 showed, on average, a slight lead of supporters of remaining in the EU of around 5% over supporters of leaving the EU (average result from six polls).

- Results of opinion polls after the referendum, June 2016 to June 2019

The change in sentiment since the referendum was explained by several factors. Among those respondents who did not vote in the 2016 referendum (for example because they were too young), but who would vote in a second referendum, were those in favor of staying in the EU with a ratio of more than 2.5: 1 in the majority. Among those who voted for Brexit in 2016, a slightly larger proportion cast doubt on their opinion at the time than among those who voted to remain in the EU. A key factor here is that respondents tend to be more pessimistic about the economic consequences of leaving the EU over time.

Petitions for a second referendum in 2016 and 2019

Four weeks before the referendum, a petition had been launched on the Internet calling for the referendum to be repeated in the event that the turnout was less than 75% and neither of the two voting options achieved 60% approval. The referendum result met both conditions.

By July 10, more than four million Internet users voted for the petition, whereupon a three-hour parliamentary debate took place in Westminster Hall on September 5, but it had no consequences. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs announced on July 9th that the government had rejected the petition; the result of the referendum on June 23 must be respected and implemented.

By 2018, former Vice Prime Minister Nick Clegg , former Prime Minister Tony Blair and the Labor Party called for a second referendum. In two test votes in the House of Commons on March 27, 2019 and April 1, 2019, the proposal to hold a second referendum was rejected with a majority of 27 votes and 12 votes respectively ( see below ).

On February 20, 2019, the British Margaret Georgiadou started a petition calling for the exit process to be stopped. The petition was intended to show that Brexit - contrary to what the government has repeatedly claimed - is no longer the will of the British people. This petition was supported by more than 6.1 million signatories, making it the largest petition ever before the UK Parliament.

On March 26, 2019, the government emphasized that it wanted to leave the EU with parliamentary support despite the petition.

On April 1, there was an unconsequential debate in Westminster Hall on this and two other petitions related to Brexit, which had the support of more than 180,000 and 170,000 signatories, respectively. A similar debate had already taken place in January 2019 after a petition calling for people to leave the EU without a withdrawal treaty received more than 130,000 signatures.

Influence on the political climate

During the Brexit discussion in Great Britain there was an increase in violence against MPs, on the one hand among Brexit supporters and, to a somewhat lesser extent, among Brexit opponents. Some MPs stopped running for fear of attacks against themselves and their families.

On October 20, 2018, there was a large demonstration in London , at which over 600,000 people demonstrated for a second referendum on Brexit.

On March 23, 2019, a second large-scale demonstration took place in London under the motto Put it to the people . It was estimated to be one of the largest demonstrations to ever take place in the UK, with more than a million participants.

Immediate economic consequences after the referendum

Foreign exchange market and monetary policy

On June 25th and again on July 7th, the bilateral exchange rate of the pound (GBP) to the US dollar fell to its weakest level since 1985. Between May 2015 and May 2016, the GBP lost almost 8% against the euro. Shortly before the referendum, many Britons exchanged their GBP balances for currencies that are considered safe havens . In addition to the dollar, the yen and the Swiss franc , gold recorded high gains. The stock indices fell 10% in Frankfurt , 8% in Tokyo , 5% in London and 2% in New York .

This price development is favorable for the UK tourism sector as well as those companies that produce primarily for export. However, all export-oriented British companies have to compensate for rising production costs through higher sales if they purchase foreign semi-finished products or capital goods in exchange for a foreign currency.

On June 27, 2016, the major rating agencies Standard & Poor’s (S&P) and Fitch Ratings downgraded the UK's creditworthiness to "AA".

Because of the economic slowdown expected after the vote, the Bank of England cut the key interest rate from 0.5% to 0.25% in early August 2016 and announced the sale of 60 billion pounds for securities in order to depress the pound rate. When the pound exchange rate reached 7-year lows against the euro and 35-year lows against the US dollar by October 2016, Theresa May's government criticized these decisions. However, the bank's governor, Mark Carney, pointed to his constitutional independence and insisted on keeping the sterling rate low in the interests of the UK economy, even at the expense of higher inflation, which would particularly affect food.

In October 2016, Standard & Poor's warned that the pound could lose its reserve currency status for the first time since the early 18th century; this could happen if the pound's share of the central banks ' currency portfolios , which stood at 4.9% at the end of 2015, falls below 3%.

Investments

A study by the Institut der Deutschen Wirtschaft in July 2018 came to the conclusion that foreign investments in the United Kingdom have declined by 80% since the referendum: after 66 billion euros annually between 2010 and 2016, only 15 billion euros were invested in 2017, while in many foreign investment in other European countries increased significantly in the same year.

On August 13, 2016, the UK government announced that it did not want to stop EU co-financed projects in the UK, but rather to cover the financing gap from its own resources, provided that the financing commitment was made before the Autumn Statements 2016 (usually in November).

Migration and Naturalization Issues

The number of EU citizens who immigrated to the United Kingdom fell from October 2017 to September 2018 to the lowest level in almost ten years. In contrast, net immigration from non-EU countries reached a high of 261,000 during this period.

After the referendum, many Britons applied for another citizenship: the number of applications for naturalizations rose in Germany, Ireland, Portugal and Sweden, among others. In 2017, around 14,900 UK citizens were naturalized in another EU country (127% more than in the previous year), including 7,493 in Germany.

Exit procedure under Prime Minister Theresa May (2016-2018)

Legal framework for the exit procedure

The negotiations run on two levels: On the one hand, Art. 50 TEU triggers the co-decision procedure until a withdrawal agreement is concluded. This falls under the sole sovereignty of the EU, so that a qualified majority in the Council according to Art. 238 (2) TFEU is sufficient on the proposal to be negotiated and no unanimity has to be achieved among the member states. That means

- 72% of the 27 states (EU countries except UK, according to Art. 50 Para. 4 TEU not entitled to vote) - d. H. a total of 20 countries agree;

- these countries must also represent at least 65% of the total population of the Union excluding the United Kingdom.

Art. 50 para. 2 TEU stipulates that the EU Parliament must approve the withdrawal agreement. The WithdrawalAgreementaccording to Art. 218 (3) TFEU is thusequatedwith the other fundamental agreements in Art. 218 (6a) TFEU. A mere hearing is not enough.

At the same time or afterwards, the EU and the United Kingdom are negotiating the so-called economic agreement, which has to regulate future relations between the EU and the UK outside the scope of the contract. This is a mixed agreement : According to the regular decision-making procedure for international agreements at EU level in accordance with Article 218 TFEU, following the approval of Parliament in accordance with Article 218 (8) TFEU, the Council must also agree unanimously; then all member states of the EU must agree to the areas that do not fall under EU sovereignty. Such an agreement must go through the ratification process in all 28 countries and, if provided for by the constitutions of the member states, also be adopted by the national parliaments.

The following applies to the exit negotiations: They end when an exit agreement has been agreed or automatically after two years at the latest, regardless of the status of the negotiations. However, the exiting country and the EU can jointly extend the negotiation period.

Negotiating positions

British positions

In the negotiations with the EU, the British rejection of the free movement of persons ( European free movement , including free movement of workers ) as one of the four fundamental freedoms of the EU is a point of contention. There are transitional arrangements for British citizens who are legally residing in other EU countries at the time of leaving the EU and for EU citizens who are legally residing in the United Kingdom at the time of leaving the EU.

In November 2016, Prime Minister Theresa May proposed that the EU states mutually guarantee the rights of residence of 3.3 million EU migrants in Britain and the rights of residence of 1.2 million British migrants in continental Europe in order to exclude this issue from the Brexit negotiations. As Home Secretary May set the goal of limiting the number of immigrants to the UK to 100,000 a year, regardless of their origin.

At the Conservative Party Conference in October 2016, Prime Minister Theresa May formulated the goal that the end of EU case law and the free movement of people from the EU were her priorities. She wanted “British companies to negotiate the maximum freedom to do business with and in the internal market - and in return to offer European companies the same rights here”, but not if this would require the sovereignty of the United Kingdom as a negotiating point.

In January 2017, May presented a twelve-point plan in a keynote address which, according to the interpretation of the media, provided for a “hard Brexit” in the German-speaking countries. H. no EU sub-membership or UK associate membership. The Prime Minister predicted that the UK would leave the European single market , customs union and the European Court of Justice and that it would negotiate with the EU on drafting follow-up treaties to replace the unwanted EU rules. The British Parliament will vote on the outcome of the exit negotiations , albeit without having a right of veto on this issue .

In the first time after the membership referendum, the British position fluctuated between the positions of either continuing to belong to the EU common market or of forming a free trade area with the EU. In both cases, the rest of the EU insisted on British consideration, including on granting freedom of movement to jobseeking citizens of EU member states.

In 2020, under the Boris Johnson administration , it also became clear that the British side wanted to reject any agreement with the EU that is linked to remaining in the European Convention on Human Rights and thus to the case law of the European Court of Human Rights , which itself does not belong to the EU. In this way, the UK would keep open the possibility of repealing the human rights convention after Brexit, possibly in a second referendum, as proposed by chief adviser Dominic Cummings in 2018.

Soft Brexit: free trade area

In the first half of 2018 it became known that May is aiming for a free trade area with the European Union, which, although not part of the EU internal market, will maintain the deep economic integration of the United Kingdom and continental Europe. This position was considered a “soft Brexit” in the United Kingdom because it contradicted the complete turn away from Europe favored by Ministers David Davis and Johnson. For large parts of the Conservative Party, a free trade agreement with the EU implies too great an external influence on the British economy, and the real goal of turning away from the EU is being missed: the United Kingdom should be able to independently conclude new free trade agreements with other states. After a government meeting in July 2018, Davis and Johnson resigned from their ministerial offices: In a document called the Checkers Plan , May expressly pleaded against a “hard Brexit”. It was able to bring together most of the members of the government behind the idea of a free trade area.

Hard Brexit: EU exit without agreement

Shortly after the EU summit in Salzburg in September 2018, Theresa May saw the Brexit negotiations as "a dead end". In Salzburg she again denied the European Union concessions on the free movement of persons for citizens of the EU member states and stated in a televised address: "No agreement is better than a bad agreement." The United Kingdom must prepare for this. The motto “no agreement” corresponds to a so-called “hard Brexit”. May's domestic political campaign for a “soft Brexit”, which should also include a free trade agreement, had thus failed for the time being. The Labor Party started another attempt at the end of August 2019 to prevent a hard Brexit.

Position of the EU

The core requirement of the EU is the inseparability of the four freedoms of the internal market. On June 29, 2016, European Council President Donald Tusk said that the UK would not have access to the European single market until it accepted the free movement of goods, capital, services and people.

Despite the initial approval of a majority of the EU states, May's proposal on migrants' rights of residence was rejected by EU Council President Tusk and German Chancellor Merkel. In February 2019, the EU Commission rejected a separate deal on the rights of the persons concerned to remain, which should also apply in the event of a no-deal Brexit.

Payment claims

According to Article 50, all obligations of a member state end on the day of exit, but the legally binding payment obligations to the EU that were assumed before the exit must also be fulfilled after the exit. The negotiating partners are obliged to negotiate the modalities of the separation and their future relationship. EU chief negotiator Michel Barnier emphasized that in the two-year negotiation period, the future relationship with the United Kingdom would only be discussed if the British negotiating partner had agreed to make payments. That is why David Davis prophesied before the House of Commons in 2017 that the dispute over money would last until the last day of the negotiations.

Barnier's payment claims are based on the EU budgetary principle. “Open bills” are part of the EU budget. This results from its composition: the first part of the budget (raised by the EU net contributors) flows immediately to the recipients every year; the second part, comprising more than a third of the total expenditure, namely the EU structural programs and the research programs , will only take effect in the following years after a binding decision has been made.

The EU manages two “budgets”: one for payment appropriations (the “Funding Commitments”) and one for commitment appropriations. Payment appropriations define how much money the EU can spend in the coming financial year. Commitment authorizations specify which commitments the EU may make and what maximum amount (for expenses that are sometimes due years later). The UK has “co-signed” both types of authorization, so to speak.

Every year the EU reports how many commitments it has made in recent years for which no money has been received (“reste à liquider”, “RAL”). This total was (as of 2016) 217 billion euros. Not every commitment is called up (e.g. because a planned project is not implemented after all or because an EU member state does not pay its own contribution to the co-financing).

The UK has EU funding commitments and payment obligations for its share of payment appropriations. In September 2017, Prime Minister May announced that she would offer the EU up to 50 billion euros as a compensation payment.

Citizenship rights for stays abroad after leaving the EU

If an agreement regulates a legally orderly exit, no visa is required for citizens of the United Kingdom to enter EU member states and, conversely, for citizens from EU member states to the UK after the UK leaves the EU: EU citizens are allowed within Spend 180 days 90 days in the UK without a visa. On March 1, 2017, a majority of the House of Lords voted for an amendment that obliges the government to guarantee the rights of EU citizens in the UK despite Brexit. In doing so, they sent the draft Brexit law back to the House of Commons. On March 13, 2017, the latter refused to approve the amendment, which the House of Lords accepted on the same day. In June 2017, the United Kingdom proposed that citizens of an EU Member State who have lived in the United Kingdom for five consecutive years be granted the status of “ settled ” after the United Kingdom left the EU equated with British citizens. Anyone who has lived in the country for a shorter period of time may stay until they have reached five years.

If no agreement should regulate the legally orderly exit, in Germany there is grandfathering for previously acquired social security benefits. Even after Brexit, apprentices may receive BAföG benefits up to completion of an apprenticeship previously started in the United Kingdom .

This transitional act does not protect those who start working in the UK after Brexit or who return to Germany after returning from there.

Negotiator

Prime Minister May appointed on July 13, 2016 David Davis for Minister for the withdrawal from the European Union , whose resignation they took on 9 July 2018th After that, May conducted the negotiations independently instead of Davis' successor Dominic Raab , who took on the role of deputy. The latter resigned on November 15, 2018 after finding that the draft treaty that Theresa May had accepted to shape the transition period for leaving the EU would result in the United Kingdom being legally bound to the EU for an unlimited period of time. Raab's successor was Stephen Barclay .

On June 25, 2016 the European Council appointed Didier Seeuws as its negotiator for the shaping of future relations between the EU and Britain, the President of the European Commission Jean-Claude Juncker appointed Michel Barnier as chief negotiator of the Commission for the preparation and Conducted the exit negotiations, and on September 8 the European Parliament appointed Guy Verhofstadt as its negotiator. This was supported by a group of members of the European Parliament, the so-called Brexit Steering Group .

On September 14th, the European Commission decided to set up an "Article 50 Task Force" for the negotiations, led by Barnier. In addition, Sabine Weyand was appointed as Barnier's deputy.

Article 50 of the EU Treaty

The actual exit process was legally initiated in accordance with Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union through the notification of the British government to the European Council . This provides that after a state's declaration of intent on its exit from the EU, an agreement will be negotiated on the details of the exit, which will also take into account the future relations of this state with the Union.

On March 29, 2017, the Prime Minister arranged for such a letter to be handed over to the President of the European Council , Donald Tusk, with the British declaration of intent ("withdrawal request") . The letter also contains a request to leave the European Atomic Energy Community . Theresa May had previously announced the Queen's speech from the throne on June 21, 2017 as the starting point of the exit process at a Conservative party conference in Birmingham on October 2, 2016 .

The Council of the European Union as a body of the heads of government of the EU member states formulates the negotiating goals. The European Commission carries out the objectives. The agreement must be adopted by the European Council on behalf of the Union by a qualified majority. If there is no majority, the state willing to leave the community must leave the community on the path of "unregulated exit". The European Parliament must also approve the outcome of the negotiations .

There was the possibility of an extension of the deadline by the European Council, but this had to be decided unanimously. A state that has left the Union and wishes to become a member again can apply for this in accordance with the procedure set out in Article 49 of the EU Treaty.

Role of the British Parliament

On the question of whether the British government can formally notify the EU of the exit under Article 50 without the consent of Parliament, seven lawsuits against the British government had already been filed at the beginning of August 2016 in order to require parliament's consent. As an example, the Supreme Court accepted the action brought by the London fund manager Gina Miller , and the hearing took place in October 2016.

On October 18, the government appealed to the court on the usual ratification procedure ( the view within government is that it is very likely that this treaty will be subject to ratification process in the usual way ), with which parliament only decides on the election whether the UK would leave the EU with or without an agreement. However, the applicant sought to enable Parliament to decide whether to remain in the EU. Since the overwhelming majority of MPs had spoken out in this regard before the EU exit referendum, the government could have lost the majority in parliament and lost the vote if only a few dissenters from its own party had taken place. The government wanted to avoid the new elections that might be necessary as a result.

The British government of Prime Minister Theresa May stuck to its position in relation to the court and the public that an explicit parliamentary vote on the exit was not necessary. On November 3, 2016, the High Court of Justice ruled that the British government must not initiate an exit from the EU without the consent of the British Parliament; On January 24, 2017 , the Supreme Court rejected an appeal by the government directed against it with a majority of 8 to 3 judges. As a justification, the court stated that the planned exit from the EU would invalidate existing (EU) law in the United Kingdom, and that this would require an Act of Parliaments , i.e. H. a parliamentary decision. The approval of the regional parliaments of Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales is not required.

On February 1, 2017, the House of Commons voted with 498 votes in favor and 114 against the Article 50 Act, which empowered the government to initiate the withdrawal process. The parties SNP (50 MPs), Plaid Cymru (3), SDLP (3) and the Liberal Democrats (8) voted unanimously against the law. Before the vote, the Labor party leadership had tried with strict instructions to mobilize the parliamentary group as closely as possible for approval. Even so, of the 232 Labor MPs, 47 voted against the law. Kenneth Clarke was the only one of 320 Conservative MPs to vote against.

The opinion of the British government is also controversial among lawyers that leaving the EU automatically leads to leaving the EEA because the United Kingdom is also a member of the EEA through the EU. On February 3, 2017, the Supreme Court dismissed a lawsuit that wanted Parliament to hold a separate vote on an exit from the EEA.

Judgment of the ECJ on the possibility of a unilateral withdrawal of the exit request

MEPs from the Scottish, British and European Parliaments had called the Scottish Court of Session on the question of whether the United Kingdom could withdraw its declaration of intent to leave ("withdrawal motion") without the consent of the other EU member states. The civil court turned to the European Court of Justice (ECJ) to assess the question .

The Advocate General Manuel Campos Sánchez-Bordona thought the UK would withdraw his statement even without the consent of the other EU countries. However, the withdrawal must not be improper, it must be formally notified to the Council before the entry into force of a withdrawal agreement or before the expiry of the 2-year period and it must be in accordance with national constitutional law. The Advocate General justified his view with the fact that, according to the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, a declaration of intent by a state can also be withdrawn as long as the legal act following the declaration has not yet entered into force. Against the background of the aspired ever closer union of the peoples of Europe, it is absurd to put obstacles in the way of a member state willing to return, provided that its decision was constitutionally and democratically made.

The European Court of Justice ruled on December 10, 2018 that a member state can effectively withdraw a declaration of intent to leave without the consent of the other EU member states. The Court of Justice largely followed the Advocate General's request in the outcome and reasoning and added that the withdrawal should not be conditional.

Great repeal bill

In British law, international treaties only become effective after they have been transposed into national law by a separate law, e.g. B. The European Communities Act 1972 , which regulates the validity of Union law in the United Kingdom.

In order to adapt national law to leave the EU, Theresa May announced in October 2016 that she would submit a Great Repeal Bill to parliament with the aim of preventing legal uncertainty from arising from the start. The main points of this law, which the government presented in a white paper on March 30, 2017 , regulate:

- The repeal of the European Communities Act 1972 and thus the continued application of Union law in the United Kingdom.

- The conversion of the EU law valid at the time of exit into British law; this is to be achieved in that

- directly applicable law, such as transforming EU regulations into UK law,

- all national laws previously enacted on the basis of EU law remain unchanged for the time being,

- the parts of EU primary law that individuals can invoke in court will also be adopted. In addition, when interpreting EU law that has been adopted, courts can continue to use the primary law valid at the time of exit,

- all previous decisions of the European Court of Justice are treated as precedents like those of the Supreme Court as well

- The creation of a statutory authorization to change the previous law after leaving the EU.

The last point in particular is controversial as it allows ministers to amend or remove laws without the prior consent of Parliament. This possibility in the British system is based on a decree of Henry VIII from the year 1539, which allows the executive branch to exercise legislative functions by ordinance. The UK Government believes that this is necessary in order to amend the large number of laws based on EU law in detail. The EU Charter of Fundamental Rights is expressly not to be adopted .

The draft law was introduced on July 13, 2017 under the name European Union (Withdrawal) Bill . On December 13, 2017, the House of Commons voted with 309 (including 11 Conservatives) to 305 votes for an amendment that obliges the government to have the agreement on the EU exit through a legislative process in parliament. On January 17, 2018, the House of Commons approved the law in its final reading with 324 to 295 votes.

In the House of Lords, the Lords approved 15 amendments. Among other things, the withdrawal date should be deleted from the law and the Charter of Fundamental Rights should be retained. In addition, a motion that the United Kingdom's membership of the European Economic Area should be retained after leaving the EU also received a majority. However, the House of Commons rejected 14 of the 15 amendments. The bill finally passed both houses of parliament on June 20, 2018, and received royal approval on June 26. It should come into force after the UK leaves the EU.

Dispute over the border between the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland

The island of Ireland has been politically divided since 1921 : While Northern Ireland remained in the United Kingdom, the Republic of Ireland first became a dominion within the Commonwealth and in 1949 a sovereign state . However, there have been no regular border controls for passengers between Ireland and Northern Ireland and the rest of the United Kingdom due to the Common Travel Area since 1921 . There are no goods controls at the border, as both countries belong to the European single market created in 1993 . Nonetheless, during the Northern Ireland conflict, military checkpoints were set up at many border crossings and most non-guarded crossings were closed.

In 1998 Ireland, the United Kingdom and the leading political parties in Northern Ireland signed the so-called Good Friday Agreement . This largely ended the civil war-like conflict in Northern Ireland, in which over 3,500 people were killed in about 30 years. The agreement confirmed the status quo with the possibility that the Northern Irish could freely choose to unite with the Republic of Ireland in the future. Although the Good Friday Agreement makes no reference to the border or controls, border controls between Ireland and Northern Ireland have subsequently been reduced. Citizens of the Republic of Ireland on the one hand and the United Kingdom on the other hand can (with minimal identity checks within a "common travel territory" English "Common Travel Area" move) in the British Isles.

Theresa May and Enda Kenny , Acting Prime Ministers of the Republic of Ireland, expressed their confidence in October 2016 that these practices would be maintained. In order to prevent illegal migration across the open Northern Irish border into the United Kingdom after Brexit, the Irish government approved a British plan in October 2016 that the British border guards would in a sense be extended to Ireland. i.e. Irish border guards prevent illegal entry at Irish ports and airports. This would prevent a new border from being created between Northern Ireland and Great Britain , the largest of the British Isles .

During the negotiations on the Brexit Treaty, both the EU and the United Kingdom emphasized that after Brexit the border between the two parts of the island should remain without goods controls (customs controls), although the Republic of Ireland as a member of the EU is part of the EU customs union However, the United Kingdom will no longer be part of the customs union after the Brexit process is complete. There will then be an external EU border between the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland, at which goods controls are required according to EU rules, unless a customs-neutral trade agreement is concluded.

In a speech to the Irish Parliament in Dublin, EU chief negotiator Michel Barnier threatened the establishment of an EU customs border with Northern Ireland if no Brexit agreement was reached, but the Irish police warned in May 2018 that 1,000 Irish police officers ( gardai ) would be necessary and there is no plan for it. As early as 2016, a study by the Dublin Institute of International and European Affairs warned against the reintroduction of border controls along the border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland: “The border would bring the nationalist community [the Catholic minority in Northern Ireland] to the Republic [Ireland] all in one Isolate dimensions in a way that has not existed in 40 years. It takes little imagination to conclude that turning back the clock would enrage nationalists enormously and fuel vocal calls for Irish unity, creating tension in the [Protestant majority] population of Northern Ireland and thus tensions within Irish-British relations would generally be tightened. "

Fallback solution ("backstop")

To avoid physical checks, the agreement on the withdrawal of the UK from the EU includes the so-called backstop protocol ( German "fallback solution" ). A solution should be available by 2020 [obsolete] to enable traffic between the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland without goods controls despite the then existing external border of the EU internal market and the EU customs union. However, if such a solution cannot be agreed during the transition period, the entire United Kingdom would remain subject to the rules of the EU customs union and the internal market for the time being, in order to prevent border controls in any case.

"Unionists", "Brino"

The party leader of the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) Arlene Foster , whose ten MPs in the lower house of the UK Parliament support the minority government of the Conservative Party, made it clear in November 2018 that the DUP MPs would not agree to any solution that only Northern Ireland, but not the rest of the United Kingdom would bind to the customs rules of the EU, since this would Northern Ireland from Britain "drive away" ( English "leaves us adrift" ).

Equal treatment for Northern Ireland and Great Britain runs counter to the interests of the “hard Brexit” advocates, who are well represented in the ruling Conservative Party. They described the remaining of the whole of the United Kingdom in the EU customs union as “Brexit in name only”, called “Brino” by the British media. In mid-November, despite the agreement between the negotiators of the European Union and Theresa May, another impasse in the Northern Ireland problem was reached.

In summary, this means that Great Britain wants to prevent a fragmentation of the national territory, and the EU a fragmentation of its internal market. However, if Great Britain waives customs duties and import controls vis-à-vis the Republic of Ireland in order to defuse the Northern Ireland conflict, this would constitute a violation of the most-favored nation principle .

Negotiations begin

Originally, negotiations on the exit agreement sought by both sides should have been concluded by October 2018. Contrary to the intention of the United Kingdom, the separation modalities should first be fully negotiated and, if all points are agreed, the future relationship between the two parties should then be negotiated. The schedule was one week of negotiations per month.

The first round of negotiations began on June 19, 2017 in Brussels under the leadership of Michel Barnier and David Davis . The British side agreed to the EU's requirement that the first round of negotiations should produce solutions for the following three issues:

- EU payment claims against the UK, estimated by journalists to be around 100 billion euros.

- The future rights of UK citizens in the EU, as well as citizens of the remaining 27 EU countries in the UK.

- The border situation between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland . A future external border of the EU can be expected here.

On the recommendation of the European Commission , the Council of the European Union decided to enter the second round of negotiations on December 15, although no negotiating point from the first round had been clarified.

For the time after leaving in March 2019, a two-year transition phase until 2021 was originally planned. On March 19, 2018, the EU Commission and the British government agreed a transition period until December 31, 2020. During the transition period, the United Kingdom would continue to have to adhere to all EU rules and continue to make financial contributions to the EU as before, but do not lose access to the EU internal market and remain part of the customs union. In the transition period, it should be clarified what the long-term partnership between the two sides can look like. Prime Minister May as well as the EU's chief negotiator Michel Barnier made it clear: ". Nothing is Agreed until everything is AGREED" ( "Nothing is agreed until everything is agreed.") The payment claims of the United Kingdom to the EU or a transitional period ( "soft Brexit ”) would only come into force within the framework of a comprehensive exit agreement, otherwise a Brexit would take place without any concessions (“ hard Brexit ”).

Draft exit agreement in November 2018

On November 14, 2018, the European Commission and the UK government presented a 585-page draft withdrawal agreement. Important contents of the agreement are regulations too

- the structuring of a multi-year transition period between the withdrawal of the United Kingdom and the conclusion of new treaties that regulate the relationship between the European Union and the United Kingdom,

- Civil rights,

- the protection of geographical indications of origin,

- territorial issues.

The draft contains a passage according to which the entire United Kingdom will form a customs union with the member states of the European Union by July 2020.

Criticism from the EU member states

Some of the other Member States criticized the draft treaty, among other things, because the problem of fishing rights was excluded from the draft treaty and has yet to be negotiated. Until now, EU fisheries have had full access to UK waters under the Common Fisheries Policy .

The ambassador of Spain to the EU called for improvements to be made to the future status of the British territory of Gibraltar , where around 10,000 Spaniards work. Without the European Union, Spain would like to clarify all questions that regulate Gibraltar's relationship with Spain in bilateral negotiations with the United Kingdom. The European Union therefore promised the Spaniards that they could check all regulations affecting Gibraltar in advance and, if necessary, prevent them.

UK review

In the United Kingdom, the draft treaty met with criticism from both exit opponents and Brexit supporters. On November 15, 2018, Northern Ireland Secretary of State Shailesh Vara, Secretary of State Dominic Raab , Secretary of Labor Esther McVey and Secretary of State Suella Braverman resigned. Prime Minister Theresa May lost her four most important Brexit ministers within three hours. The rate of the British pound fell.

Critics and opponents of the Prime Minister gathered in the Conservative Party. In addition to the resigned ministers, these included the long-time May critic Jacob Rees-Mogg , who on November 15, 2018 openly called for a vote of no confidence in the Prime Minister, the former party chairman Iain Duncan Smith and the ministers Davis and Johnson, who resigned in July 2018.

Decision of the EU bodies

On November 25, 2018, the heads of government of the 27 states remaining in the EU approved the draft treaty at a special summit of the European Council . The European Parliament approved the agreement on January 29, 2020 .

First vote on May's draft contract

| Political party | Therefore | On the other hand |

|---|---|---|

| conservative | 196 | 118 |

| Labor | 3 | 248 |

| SNP | 0 | 35 |

| Liberal Democrats | 0 | 11th |

| DUP | 0 | 10 |

| Plaid Cymru | 0 | 4th |

| Green party | 0 | 1 |

| Independent | 3 | 5 |

| total | 202 | 432 |

Prime Minister May postponed the vote in the House of Commons on the draft, scheduled for December 11, 2018, because it was rejected not only by the other parties, but also by numerous conservatives. May cited the main reason that the problem of the border between the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland would not be satisfactorily solved by the previously agreed backstop . The backstop also met with resistance from many Brexit supporters in the lower house.

Prime Minister Theresa May had to face a vote of no confidence within the lower house parliamentary group of the Conservative Party on December 12, 2018 , which trusted her with 200 votes to 117. According to the party rules, no new vote could be requested within one year.

The House of Commons voting debate took place on January 15, 2019 and ended with 202 votes in favor and 432 votes against the draft treaty. More than a third of the conservative parliamentary group in the lower house voted against the agreement negotiated by their own government. The motives of the opponents of the agreement were different: firstly, a fundamental opposition to "Brexit" and the demand for a second EU referendum among the EU-friendly parties (Liberal Democrats, SNP, Green Party, Plaid Cymru), secondly, the efforts of the Labor Party, to force the resignation of the government and new elections by losing the vote, and thirdly, the dissatisfaction of conservative “Brexit” supporters with individual points of the agreement, especially with regard to Northern Ireland (Conservatives, DUP).

Immediately after the vote, the Prime Minister declared her willingness to face a vote of confidence "if the opposition so wished". Opposition leader Corbyn then submitted a motion for a vote of no confidence. The following day the lower house of the May government expressed its confidence with 325 to 306 votes.

Renegotiations with the EU

A "Plan B" for Brexit, enforced by the House of Commons on January 21, 2019 and presented by Theresa May on that day in the British House of Commons, was seen as a mere variant of their "Plan A", except that the backstop had to be renegotiated with the EU. In the meantime, forces formed in the House of Commons to promote alternative ways out of the stalemate .

16 majority vote, the House Theresa May on 29 January issued a mandate to cooperate with the EU on an "open border" between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland to negotiate, be performed on the no controls, despite an EU border are would. The EU had already announced to the UK weeks earlier that this solution was not wanted. On February 8, 2019, May met Ireland’s Prime Minister Leo Varadkar for the first time since the withdrawal agreement failed.

On February 14, 2019, the MPs in the lower house voted 303 to 258 against a government resolution for a mandate for renegotiations on the Brexit deal with the EU and a rejection of the EU exit without an agreement. Prime Minister Theresa May suffered another vote defeat.

| Political party | Therefore | On the other hand |

|---|---|---|

| conservative | 235 | 75 |

| Labor | 3 | 238 |

| SNP | 0 | 35 |

| Liberal Democrats | 0 | 11th |

| DUP | 0 | 10 |

| TIG | 0 | 11th |

| Plaid Cymru | 0 | 4th |

| Green party | 0 | 1 |

| Independent | 3 | 6th |

| total | 242 | 391 |

Second vote on May's draft contract

In view of the approaching no-deal Brexit , three British ministers - Greg Clark , Amber Rudd and David Gauke - spoke out in favor of postponing the exit date for the first time on February 23, 2019 .

On February 24, 2019, Prime Minister May announced that on March 12, 2019, parliament would “finally” vote on the EU exit treaty negotiated by her government. If the contract had been accepted, the option of a regulated exit from the EU on March 29, 2019 would have continued to exist. If parliament on March 12, 2019 does not approve the exit agreement negotiated by your government, there will be a vote on March 14, 2019 on whether there should be an unregulated Brexit on March 29, 2019 or a postponement of the exit date.

In a departure from their previous position, the leadership of the Labor Party declared on February 25, 2019 that they would support the call for a second Brexit referendum if their own proposal for a Brexit agreement were to be rejected in parliament on February 28, 2019 .

The second vote on the draft contract took place on March 12, 2019. In the previous weeks, the Prime Minister had unsuccessfully sought concessions in various European capitals.

The draft contract was again clearly rejected by the House of Commons, albeit with a smaller majority than in January. This time the Independent Group (TIG), a grouping of eight former Labor and three Conservative MPs, was added to the negative parties .

Vote against the disorderly exit from the EU

On March 13, a majority of MPs voted against a disorderly Brexit (321 yes to 278 no) after a previously adopted amendment (312 yes to 308 no) had removed the time limit from the main motion. This decision was not legally binding.

First postponement of the departure date

After the House of Commons approved the motion to postpone the EU's exit on March 14 with 412 votes in favor and 202 against, May applied to the President of the European Council Donald Tusk on March 20, 2019 for the first extension of the EU's exit to 30 June 2019. The Prime Minister outlined two possible scenarios: If the House of Commons still approved her government's exit treaty, only a short extension of the deadline would be necessary. If, on the other hand, the House of Commons continued to refuse, the exit from the EU would have to be postponed to a “much more distant point in time”; in the latter case, the United Kingdom would vote in the 2019 European elections , which were scheduled for May 23-26. This choice could also become a mood test.

At the summit on March 21, the 27 other EU states decided to postpone it until April 12, 2019.

| Political party | Therefore | On the other hand |

|---|---|---|

| conservative | 277 | 34 |

| Labor | 5 | 234 |

| SNP | 0 | 34 |

| Liberal Democrats | 0 | 11th |

| DUP | 0 | 10 |

| TIG | 0 | 11th |

| Plaid Cymru | 0 | 4th |

| Green party | 0 | 1 |

| Independent | 4th | 5 |

| total | 286 | 344 |

Third vote on May's draft contract

| poll | date | Therefore | On the other hand |

|---|---|---|---|

| First | 15. January | 202 | 432 |

| Second | March 12th | 242 | 391 |

| third | March 29th | 286 | 344 |

Speaker John Bercow stated on March 18 that a third vote on the government bill, planned for March 20, 2019, would not be possible without a substantive change. According to a parliamentary rule of April 2, 1604, the same bill could not be put to the vote again in the same session without changing the content.

Since there was no majority in favor of the withdrawal agreement, the government did not put the draft back for a vote in the lower house.

On March 27, 2019, Theresa May offered MPs from her own party that she would step down as Prime Minister if the British House of Commons approves the negotiated exit agreement.

In order to get the Speaker of Parliament Bercow to approve a third vote on the Withdrawal Treaty, the British government made use of legal finesse and split the contract into two parts on March 28, 2019:

- the part of the contract on the negotiated exit modalities

- the part of the treaty on future UK-EU relations

On March 29, 2019, which was long considered to be the date of the EU's exit, the British government submitted the negotiated exit agreement to the MPs for a vote. According to the latest statements by the European Council and the British government, the adoption of the entire agreement on March 29, 2019 was the last chance to prevent an exit without an agreement on April 12, 2019. It was believed that the UK government wanted to build pressure to get the majority of MPs to accept. The MPs of the lower house already showed their majority rejection in the first of the two scheduled votes, which concerned the modalities of the treaty. The European Union immediately scheduled a meeting of the European Council, without a representation of the United Kingdom, for April 10, 2019.

Votes on alternatives to May's resignation contract

In order to counter the muddled situation, the House of Commons considered to vote on its own initiative and to sound out for which of the possible exit scenarios a parliamentary majority could possibly be found.

First round of voting

In the first round on March 27, 8 proposals were voted on. The parliamentarians voted to take control of the agenda from the government on March 27, 2019. On that day they carried out indicative votes - non-binding test votes - in order to identify majority capabilities of alternatives to the rejected exit agreement. However, the parliamentarians could not agree on an alternative to the negotiated exit agreement. However, the initiators of the trial vote emphasized that this was not the purpose of the exercise at all. Rather, they want to find out which options have the highest chances of approval, so that they can then be queried again in a runoff election .

| First round of test votes on alternatives to the Withdrawal Agreement on March 27, 2019 | ||||

| variant | Yes | no | Diff. | contents |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Second EU referendum | 268 | 295 | 27 | Holding a second referendum |

| Remaining in a customs union | 265 | 271 | 6th | The UK is leaving the EU without a withdrawal agreement , but should try to join the European Customs Union through negotiations with the EU immediately after leaving . |

| Labor Party concept for leaving the EU | 237 | 307 | 70 | The UK leaves the EU with the exit agreement, remains in the customs union and is based on the existing and future rules of the European internal market . |

| Norwegian model of EU partnership | 189 | 283 | 94 | The UK remains in the European Economic Area and the Customs Union and joins the European Free Trade Association . |

| Withdrawal from the EU exit in the event of the impending unregulated exit from the EU | 184 | 293 | 109 | In order to avoid an exit without an agreement, the government should be obliged to hold a vote at least two meeting days before leaving the EU on whether the country should leave without a treaty. If this is rejected, London should revoke the resignation. |