Privateering

As a privateering or as piracy are acts of violence and looting by Sea to state-mandated private sailors called. From the Middle Ages to the beginning of the 19th century, it was a recognized practice that states or sovereigns, in order to support their naval forces in times of war, commissioned or authorized private sailors to use their flag to use force against enemy ships and to plunder them. Privateer was mainly directed against hostile sea trade ( trade war ). Instead of a pay , these seafarers were entitled to withhold part or all of the spoils of war (prize). With the signing of the Paris Declaration of the Law of the Sea on April 16, 1856, the gradual international outlawing of piracy began.

Those involved in privateering are called privateers or pirates . In addition, there are context-dependent terms such as corsairs , buccaneers and flibustiers .

Privateer is to be distinguished from piracy . The pirate acts illegally and decides for himself which ship to board, which booty interests him and how to use it.

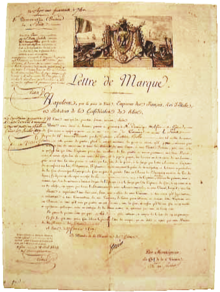

Letter of piracy

Under certain circumstances, a letter of security was issued as a formal basis . The letter of piracy was a document that a government issued to a private person who was thereby authorized to drive the pirate. This means that the captain had the right or the order to capture ( board ) or sink ships of another nation . The pirate acted officially on behalf of the issuing state. At the same time, the pirate was promised protection in the ports of the exhibiting nation. In return, the privateer captain had to transfer part of the booty, the so-called prize , to the issuing state. On board, the share of the booty or the proceeds from it, the prize money , was distributed according to a fixed key.

history

Letters of piracy emerged in the 12th century as part of the regulation of what had been practically no law at sea until then. Piracy remained an accepted part of naval warfare until the 19th century . With the letter of piracy , "naval warfare on behalf" was distinguished from piracy . Sometimes, however, privateer captains took advantage of the letter of credit to engage in piracy on the side.

The main aim of the privateers were merchant ships .

Letters of piracy were especially issued when states wanted to strengthen their maritime power in the short term or even just needed money. A typical example is Elizabethan England , which recruited Francis Drake and other captains to weaken Spain on the one hand and to generate income for building a large navy on the other. In this way they came to nautically highly qualified captains from other nations. In some cases, the letter of piracy was also used to deter pirates from threatening their own ships.

Letters of piracy were issued in particular by Great Britain , France , the Hanseatic cities and the USA . The Constitution of the United States (Article 1, Section 8) expressly assigns the authority to issue letters of title to Congress . The legal privateer in North America's War of Independence allegedly cost England the equivalent of six million dollars in trade. In 1812, 500 US privateers liquidated 13 percent of British sea trade.

The issuance of letters of war was internationally outlawed in 1856 by the Paris Declaration . The USA, Spain and Mexico did not join this declaration of the law of the sea, but in the case of the USA because they wanted a more extensive and complete abolition of the right of prey, which in turn failed because of Great Britain. The declaration did not mean the end of naval warfare against merchant ships. The prize law was only restricted from now on regular warships.

Well-known pirates and privateers

- the Vitalienbrüder under Klaus Störtebeker (around 1360-1401) (Danish- Mecklenburg conflict in the late 14th century), later as pirates

- Paul Beneke (early 15th century - around 1480), ( Hanso-English War 1469–1474)

- Sir Francis Drake (around 1540–1596), (Anglo-Spanish conflict from 1585 as part of the Eighty Years War ), previously piracy under the tolerance of the Crown

- Sir Walter Raleigh (1552 or 1554-1618), (Anglo-Spanish conflict from 1585 as part of the Eighty Years' War ), as a shipowner, did not personally conduct privateers

- Flibustiers (on the French side) and Bukaniers (on the English side) in the Caribbean 17./18. Century

- Benjamin Hornigold (1680–1719), ( War of the Spanish Succession ), later a brief pirate, finally a pirate fighter

- Woodes Rogers (around 1679–1732), ( War of the Spanish Succession )

- Robert Surcouf (1773-1827), ( Napoleonic Wars ), also called Reeder

- Jacques Cassard (1679-1740)

Sometimes sea officers or warships that waged trade wars are incorrectly referred to as pirates. B .:

- Piet Pieterszoon Heyn (1577–1629), ( Eighty Years War )

- Graf Luckner (1881–1966), (the "sea devil") on the auxiliary cruiser SMS Seeadler in the First World War

- Nikolaus Graf zu Dohna-Schlodien (1879–1956), commander of the auxiliary cruiser SMS Möve in the First World War

- Light cruiser Emden (Germany) in the First World War

- the German auxiliary cruiser Pinguin in World War II

Words and Etymology

Capers is a loan word from Frisian that came into the German language via the Lower Saxon language and Dutch . It is derived from kapia (to buy), perhaps also from kapen (to look out, to ambush) or from the Latin capere (to catch).

Freibeuter is derived from Middle Low German vrībūter with the same meaning.

The word corsairs is an equivalent borrowing of the Romansh-language term for pirate drivers ( French corsaire , Provencal corsari , Spanish corsario , Italian corsaro ). In a narrow sense, it refers to the pirates residing in the Mediterranean (e.g. barbarian corsairs and Maltese corsairs). Ultimately, it goes back to the Latin cursus “prey”, actually “run” or cursor “runner”. A later folk etymology wrongly associated the corsairs with the island of Corsica .

Related topics

Of trade war is when the goal is to damage the enemy by damaging trade (damage to port facilities, blockade of shipping routes, capture of merchant ships). There can also be profits for the conqueror, for example through prize money or auction prizes.

literature

- Robert Bohn : The pirates. 2nd Edition. Verlag CH Beck, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-406-48027-6 .

- David Cordingly: Under the black flag. Legend and reality of pirate life. dtv, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-423-30817-6 .

- Daniel Heller-Roazen: The enemy of all : the pirate and the law. S. Fischer Verlag, 2010, ISBN 3-10-031410-7 .

Web links

Remarks

- ↑ Privateer. In: duden.de - spelling, meaning, definition, synonyms, origin. Retrieved January 12, 2017 .

- ↑ Adrian Tinniswood: Pirates of Barbary - Corsairs, Conquest, and Captivity in the Seventeenth Century . Riverhead Books, New York 2010, ISBN 978-1-101-44531-0 , chapter 2.

- ↑ Almut Hinz: The "piracy of the barbarian states" in the light of European and Islamic international law . In: Constitution and Law in Übersee / Law and Politics in Africa, Asia and Latin America, Vol. 39, No. 1 (1st quarter 2006), pp. 46-65, JSTOR 43239304 , pp. 48-49.

- ↑ Heinz Dieter Jopp, Roland Kaestner: Analysis of the maritime violence in the environment of the barbarian states from the 16th to the 19th century. A case study . PiraT Working Papers on Maritime Security No. 5, May 2011, p. 9.

- ^ Angus Konstam: Pirates. The Complete History from 1300 BC to the present day . First Lyons Press, 2011, ISBN 978-0-7627-7395-4 , p. 9.