UK EU membership

The history of the United Kingdom's membership in the European Union began on January 1, 1973 when the United Kingdom joined the European Economic Community (EEC), a forerunner organization to the European Union (EU). Membership ended after 47 years when the United Kingdom left the EU (“Brexit”) on January 31, 2020.

The future relationship between the UK and the EU is currently being negotiated during a so-called transition period, which will last until December 31, 2020 if it is not extended by June 30, 2020 at the latest.

prehistory

Former British Prime Minister Winston Churchill was a prominent proponent of European integration after World War II (see United States of Europe ). He gave France and Germany a leading role. Great Britain should be a partner of this united Europe, but not take part in its unification process itself.

The United Kingdom was not a signatory to the Treaty of Rome , which established the European Economic Community (EEC) in 1957, and instead co-founded the rival European Free Trade Association EFTA in 1960 .

The United Kingdom applied for membership of the EEC in both 1961 and 1967. These applications for membership failed because of the veto of French President Charles de Gaulle , who held that "a number of aspects of Britain's economy, from labor practices to agriculture, [...] made Britain incompatible with Europe." After de Gaulle's resignation the United Kingdom made its third application for membership in 1970.

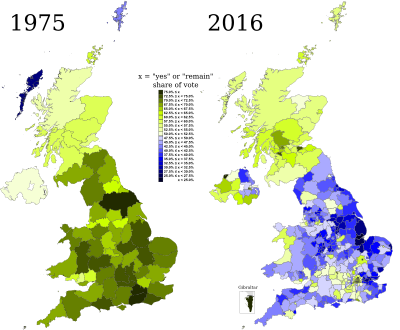

From joining the EEC 1973 to 1992

The United Kingdom joined the EEC on January 1, 1973 under the Conservative government of Edward Heath . In the 1975 referendum , with 64% turnout, 67% of British voters were in favor of membership. While the Conservatives and their chairwoman Margaret Thatcher (since 1975) were predominantly pro-European, the most prominent EEC critics in the 1970s and early 1980s were in the ranks of the Labor Party , especially in the left wing. However, shortly after taking office as Prime Minister in 1979, Thatcher demanded a reduction in British payments to the EC and was able to enforce this after a few years.

While leading continental European politicians such as the EEC Commission President Jacques Delors , the French President François Mitterrand and the German Chancellor Helmut Kohl continued to work towards the goal of a political union of European states, the political conservatives emerged as skeptics of a political unification. On September 20, 1988, Thatcher spoke in a speech in Bruges in favor of a Europe of independent, sovereign states and rejected the idea of a European federal state modeled on the United States of America . At the same time, she criticized the EEC policy, especially the common agricultural policy , as "cumbersome, inefficient and extremely costly" and called for appropriate reforms in the market economy sense.

The United Kingdom joined the European Monetary System (EMS) in October 1990 , thereby accepting a partial relinquishment of its central bank's freedom of choice . The exchange rate of the British pound to the other currencies in the " currency basket " of the European currency unit (ECU), including the D-Mark , was only allowed to move within a certain corridor . A month later, Thatcher was overthrown in an internal party revolt and John Major assumed the office of Prime Minister.

Maastricht Treaties 1992 and Lisbon 2007

Prime Minister Major had the Maastricht Treaty signed on February 7, 1992 . With the treaty, the European Union (EU) was founded as a superordinate association for the European Communities , for the common foreign and security policy and for cooperation in the areas of justice and home affairs . In the treaty, the signatory states undertook to introduce a common currency by January 1, 1999 at the latest. However, the United Kingdom and Denmark only signed the treaty with a so-called opt-out clause, which allowed them to decide for themselves whether to join the monetary union. The United Kingdom also did not sign the so-called Social Protocol , which was annexed to the treaty and contained provisions on minimum labor standards.

The Maastricht Treaty was unpopular within the Conservative Party. A faction of “Maastricht rebels” put pressure on the prime minister. Major was only able to push through the ratification of the Maastricht Treaty in 1993 by threatening to resign and hold new elections.

On September 16, 1992, also known as Black Wednesday , massive speculation against the British pound, mainly operated by financial investor George Soros , forced the pound out of the European monetary system . The Italian lira followed the next day. The Bank of England's unsuccessful support purchases cost billions of pounds. An economic crisis followed with high unemployment of up to 10%. In the long term, the electorate's confidence in the economic policy competence of the Conservative Party suffered, and belief in a European currency project was permanently shaken.

As a result, the idea of a referendum on whether the United Kingdom would leave the EU first came up in the 1990s. In 1994, billionaire James Goldsmith founded the Referendum Party , but it failed to win a constituency and dissolved shortly after the death of its founder in 1997. The Eurosceptic party UKIP , founded in 1991, gained greater importance instead, but lagged far behind the election results of the established parties.

In the 1997 general election, the Labor Party under Tony Blair assumed government responsibility by a large majority , who advocated EU membership and announced a referendum on the kingdom's accession to the so-called " Eurozone ". The Chancellor of the Exchequer, Gordon Brown, appointed by Blair, intervened successfully against a possible replacement of the pound by the euro , and the referendum on this issue was never held.

Brown was Blair's successor from 2007 to 2010. He signed the Lisbon Treaty in December 2007 , albeit not during the official ceremony, but a few hours later because at the moment in question he had "an appointment with representatives of committees". Article 50 of the treaty regulates the withdrawal of a member state for the first time.

migration

Up until 2004, compared to later years, there was a low level of immigration to the UK, of around 10,000 nationals from other EU members per year. When ten new countries from Eastern, South-Eastern and Southern Europe joined the EU in 2004 , most of the older members, such as Germany or Austria, limited the influx of workers from the acceding countries through transitional regulations . In Germany the unemployment rate was 11% in 2004 and 2005, in the United Kingdom it was only around 5% in the same period, and there was high demand for labor in some sectors.

The government of Tony Blair , in agreement with representatives from the British economy, waived restrictions on workers from the new EU countries. On the contrary, certain groups of people, such as Polish doctors, were specifically recruited. As a result, immigration from these countries rose sharply, especially from Poland and Lithuania. Between 1998 and 2008, the number of Poles living in the UK rose from 100,000 to 600,000. In June 2016, 2.1 million people from other European countries were working in the UK.

The rise in unemployment as a presumed consequence of the financial crisis from 2007 onwards made the British aware of the competition between immigrants on the labor market and increased the feeling of foreign infiltration in parts of the population . The massive immigration was made partly responsible for the shortages in the housing market and bottlenecks in the National Health Service (NHS). The British authorities did not provide the incoming immigrants with adequate housing. The resulting wild migrant camps were featured prominently in Brexit-friendly parts of the press, for example the Manchester Jungle in 2015 .

Cameron's path to the exit referendum (2010-2015)

Conservative David Cameron has been the moderate Eurosceptic prime minister since the 2010 general election . Until 2015 he led a coalition with the Liberal Democrats; Since the general election in 2015 , which he clearly won , he was able to lead a sole government again thanks to the majority suffrage, although the Europe-critical UK Independence Party had grown enormously in popularity and the British party system had generally broken up. This is attributed to Cameron's commitment to the Scottish independence referendum in 2014 and his promise of a future referendum on British EU membership.

On June 29, 2012, Cameron rejected the call by traditional EU skeptics in the Conservative Party for an EU membership referendum, but declared on the next day that he wanted to achieve "the best for the UK" with regard to the EU. He may also consider holding a referendum for this when the time is right.

On January 23, 2013, Cameron announced that if he was re-elected in May 2015 , he would have a referendum held in the United Kingdom by 2017 at the latest on whether the country would remain in the EU. Before that, he wanted to negotiate with the European partners in order to reform the EU, particularly with regard to immigration and state sovereignty. On the same day, opposition leader Ed Miliband accused him of proposing the referendum in response to rising polls from the EU-critical UKIP in the House of Commons debate. According to Cameron's announcements, support for the EU increased in the polls until around mid-2015.

The 2014 European elections showed that the camp of staunch EU opponents was solidifying within the electorate and that EU-skeptical attitudes had an impact far down the middle. With a low turnout of only 35.6%, UKIP became the strongest force in the UK for the first time with 27.5% and is now a serious contender for national elections as well. In the 2015 general election , UKIP won almost four million votes (12.6%), but due to the electoral system this resulted in only one of 650 lower house seats. The Conservatives, on the other hand, won an absolute majority of the seats. UKIP drew its supporters primarily from the Conservative Party's electorate.

The EU referendum bill, introduced by Cameron after the general election, was passed in December 2015.

The wording of the voting question under Article 1 was: “ Should the United Kingdom remain a member of the European Union or leave the European Union? ” The possible answers were “ Remain a member of the European Union ”( Remain a member of the European Union ) and“ Leave the European Union ”.

Developments in 2016

Reform negotiations with the EU

The final phase of negotiations between the UK and the EU began at the end of January 2016. David Cameron's main demands on the EU concerned four points:

- EU countries without a euro should not be disadvantaged by the international community.

- Bureaucracy must be reduced.

- It had to be agreed that the contractually anchored goal of an ever closer union should no longer apply to the United Kingdom.

- The immigration of citizens of other EU member states must be reduced.

It was foreseeable that the voting behavior in the referendum would depend on the outcome of the EU reform negotiations, in particular on the subjects of “discrimination against the United Kingdom by the euro zone countries” and “immigration”. An agreement was reached at the final summit meeting on February 18 and 19 in Brussels. The central reform demand to limit immigration was resolved in such a way that every EU country could apply to the EU Commission for an “immigration emergency”; if the Commission decides that such an emergency exists, the affected EU country will be allowed to pay reduced social benefits to newly arriving EU foreigners for four years. On February 20, Cameron announced June 23, 2016 as the date for the referendum in London.

Domestic dispute

For the opponents of British EU membership, the reforms did not go far enough. On February 21, 2016, London's former Mayor Boris Johnson (Conservative Party) announced that he would join the campaign to leave the EU after making a strong case for the EU two days earlier. Among other things, he spread the slogan on his campaign bus the controversial claim that the UK is transferring £ 350 million a week to the EU, which would be better invested in the UK health service. In fact, the estimated amount being transferred was £ 248 million per week. The representatives of the Remain campaign (Prime Minister Cameron and his Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne ) pointed out the importance of the EU single market for the British economy.

Immigration became a key issue in the political controversy leading up to the 2016 EU membership referendum. Brexit supporters argued that the UK must regain control of its borders in order to curb immigration. Johnson and his colleagues stressed that immigration must be brought under control along the lines of the Australian model . The immigration compromise with the EU, on the other hand, was hardly used as an argument by the Remain campaign.

The British businessman Arron Banks supported the British independence party UKIP under its chairman Nigel Farage and the Brexit campaign Leave.EU, which he co-founded, with a total of twelve million pounds, the highest known political donation in the United Kingdom to date. Where Banks, who first denied Russian contacts in connection with his promotion of Brexit, then had to admit the money for this donation based on his own emails, became the subject of official investigations.

Referendum 2016

In the referendum on June 23, 2016, the turnout was 72.2%, a total of 33,551,983 eligible voters cast a valid vote. 51.89% of them voted for the UK to leave the EU and 48.11% to stay. In EU-friendly Scotland and among the EU-friendly younger population, voter turnout was above average.

The referendum was a purely consultative referendum and was neither binding on the government nor on parliament. Nonetheless, it was a decisive event on the way to leaving the EU.

Further development up to 2020 exit from the EU

Survey results

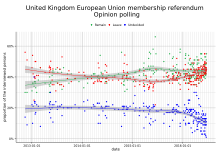

Surveys since joining the EEC in 1973 until the end of 2015 mostly showed approval of EEC or EU membership. A prominent exception was the year 1980, the first year in office of Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, in which, in surveys, the highest rejection ever measured was found at 65% (against the EEC) and 26% (for the EEC). After Thatcher negotiated a discount on British contributions in 1984, EEC supporters always had the upper hand in the polls, with the exception of 2000, when Prime Minister Tony Blair temporarily advocated closer ties to the EU, including the introduction of the euro, and around 2011, when immigration to the UK was becoming increasingly noticeable. In December 2015, according to the market research institute ComRes , there was still a clear majority in favor of remaining in the EU, but voting behavior would depend heavily on the outcome of the EU reform negotiations, especially with regard to the issues of "discrimination against Britain by the euro zone countries" and "immigration".

In most of the polls since mid-2014, the majority of voters voted for their country to remain in the EU. In the last few months before the referendum on June 23, 2016, the camps of Brexit supporters and Brexit opponents were almost equally strong in surveys. The organization NatCen Social Research established the website whatukthinks.org and published on it as a poll of polls the mean values from six current polls on potential voter behavior in the referendum on whether the United Kingdom should remain in the European Union. Since October 2015, the Brexit opponents have always been ahead by a few percentage points, only on May 12, 2016 and between June 12 and June 17, 2016, the Brexit supporters led by a narrow majority.

Labor MP Jo Cox was murdered on June 16, 2016 . The attacker shouted “Britain first!” Cox had advocated ethnic diversity in her constituency, EU membership and, in particular, the admission of more refugees. Both camps suspended their campaigns for three days and continued on June 19. A memorial session for Jo Cox was held in Parliament on June 20th.

After the murder of Jo Cox, the mood seemed to change again in favor of the Brexit opponents, according to the polls. Six polls in the last week before the referendum (from June 16 to 22) showed that opponents of Brexit had an average lead of 52% to 48%. On the day before the referendum, the bookmakers at the betting shops estimated the probability of a Brexit at around 25%. The outcome of the referendum on June 23 came as a surprise to many.

literature

- Mathias Häussler: A British special path? A research report on the role of Great Britain in European integration since 1945. In: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte 67, 2019, pp. 263–286 ( online ).

- Gabriel Rath: Brexitannia: The story of an alienation; Why Britain voted for Brexit. Braumüller, Vienna 2016, ISBN 978-3-99100-196-6

Individual evidence

- ^ Winston Churchill: Speech to the academic youth of September 19, 1946 (Zurich).

- ^ Churchill's vision of the United States of Europe , Gerhard Altmann, clio-online, 2016

- ↑ René Schwok: European Free Trade Association (EFTA). In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland . October 29, 2009. Retrieved October 22, 2018 .

- ↑ Ulrich Brasche : European integration: economy, expansion and regional effects . 3. Edition. Verlag Oldenbourg, Munich 2013, ISBN 978-3-486-71657-3 , p. 506 .

- ↑ De Gaulle says 'non' to Britain - again. In: bbc.co.uk . Retrieved March 9, 2016 .

- ^ Britain joins the EEC. In: bbc.co.uk . Retrieved March 9, 2016 .

- ↑ See The New Hope for Britain. In: politicsresources.net, Labor Party material . 1983, archived from the original on September 24, 2015 ; accessed on September 17, 2016 (English): "A member of it (Note: of the EEC ) has made it more difficult for us to deal with our economic and industrial problems"

- ↑ See Detlev Mares: Margaret Thatcher. The dramatization of the political, Gleichen / Zurich: Muster-Schmidt Verlag, 2nd edition 2018, pp. 84–91.

- ^ Speech to the College of Europe ("The Bruges Speech"). In: margaretthatcher.org, Margaret Thatcher Foundation. September 20, 1988, accessed December 23, 2015 .

- ↑ Treasury papers reveal cost of Black Wednesday. In: theguardian.com . February 9, 2005, accessed December 26, 2015 .

- ↑ Departure into a new era. In: orf.at . December 13, 2007, accessed July 5, 2016 .

- ↑ Barriers still exist in larger EU. In: bbc.co.uk . May 1, 2005, accessed July 5, 2016 .

- ↑ Nick Clark, Jane Hardy: Free Movement of Workers in the EU: The Case of Great Britain . Ed .: Friedrich Ebert Foundation . FES, Berlin 2011, ISBN 978-3-86872-687-9 ( fes.de [PDF]).

- ↑ Thomas Dudek: Eastern Europeans in Great Britain: Why Brexit is also a Polexit. In: Spiegel online. March 27, 2019, accessed March 29, 2019 .

- ^ Portrait of UK's eastern European migrants. In: theguardian.com . January 17, 2010, accessed July 19, 2016 .

- ↑ see references at en.wikipedia.org: Migrations from Poland since EU accession

- ↑ Inside the British Town Where 1 in 3 Are EU Migrants. In: time .com. June 7, 2016, accessed on July 23, 2016 .

- ^ Immigration 'harming communities'. In: bbc.co.uk . July 16, 2008, accessed July 5, 2016 .

- ^ Mapping migration from the new EU countries. In: bbc.co.uk . April 30, 2008, accessed February 19, 2015 .

- ↑ Ian Kershaw : Brexit: special role backwards zeit.de, March 6, 2019.

- ↑ Inside the Manchester Jungle: Homeless migrants set up shanty camp in city center. In: express.co.uk . November 12, 2015, accessed July 5, 2016 .

- ^ Cameron defies Tory right over EU referendum. In: theguardian.com . June 29, 2012, accessed December 30, 2015 .

- ↑ We need to be clear about the best way of getting what is best for Britain. In: telegraph.co.uk . June 30, 2012, accessed December 30, 2015 .

- ↑ Cameron announces referendum on EU membership. In: kas.de . January 24, 2013, accessed July 5, 2016 .

- ^ David Cameron's EU speech - full text. In: theguardian.com . January 23, 2013, accessed December 30, 2015 .

- ↑ David Cameron promises in / out referendum on EU. In: bbc.co.uk . January 23, 2013, accessed June 26, 2016 .

- ↑ Strong Farage, Weak Cameron. In: Spiegel Online . May 26, 2014, accessed June 29, 2016 .

- ↑ Voter Migration 2010–2015. In: electoralcalculus.co.uk. May 30, 2015, accessed July 12, 2017 .

- ^ European Union Referendum Act 2015. In: gov.uk, The National Archives . December 17, 2015, accessed July 5, 2016 .

- ↑ UK proposals, legal impact of an exit and alternatives to membership. In: parliament.uk . February 12, 2016, accessed July 5, 2016 .

- ↑ This is what the ballot paper for the EU referendum vote will look like. In: telegraph.co.uk . January 26, 2016, accessed October 23, 2018 .

- ↑ A Cameron claim has the highest contention factor. In: Welt Online . January 29, 2016. Retrieved July 9, 2016 .

- ↑ a b Failure to win key reforms could swing UK's EU referendum vote. In: openeurope.org.uk . December 16, 2015, accessed October 22, 2018 .

- ↑ The EU has done its duty. In: faz.net . February 20, 2016, accessed October 23, 2018 .

- ↑ The British vote on June 23 to remain in the EU. In: faz.net . February 20, 2016, accessed February 20, 2016 .

- ↑ Boris Johnson joins campaign to leave EU. In: theguardian.com . February 21, 2016, accessed June 30, 2016 .

- ^ Boris Johnson's previously secret article backing Britain in the EU. In: standard.co.uk . October 16, 2016, accessed October 23, 2018 .

- ↑ Greenpeace replaces Brexit battle bus 'lies' with 'messages of hope' in Westminster stunt. In: telegraph.co.uk . June 18, 2016, accessed October 2, 2016 .

- ↑ UK does get back some of £ 350m it sends to EU, Boris Johnson admits. In: itv.com . May 11, 2016, accessed September 7, 2016 .

- ↑ Why Vote Leave's £ 350m weekly EU cost claim is wrong. In: theguardian.com . June 10, 2016, accessed June 21, 2016 .

- ↑ Immigration: Threat or Opportunity? In: bbc.com . June 18, 2016, accessed February 19, 2017 .

- ↑ Juncker rules out renegotiations on reform package with the British. In: Reuters .com. July 22, 2016, accessed October 23, 2018 .

- ^ Arron Banks: self-styled bad boy and bankroller of Brexit

- ↑ Cathrin Kahlweit: British investigative authority for serious and organized crime NCA is investigating the prominent Brexit supporter Arron Banks , Süddeutsche Zeitung, online November 8, 2018, access January 19, 2019

- ↑ Great Britain is so divided. In: Spiegel Online . June 24, 2016. Retrieved June 29, 2016 .

- ↑ 40 years of British views on 'in or out' of Europe. In: theconversation.com. June 21, 2016, accessed November 3, 2016 .

- ↑ New home for EU Referendum public opinion data launched. In: whatukthinks.org. 2015, accessed on October 23, 2018 .

- ↑ 8 reasons why Syrians will never forget Jo Cox. In: newstatesman.com . October 24, 2018, accessed June 22, 2016 .

- ↑ British MP Jo Cox honored as EU referendum campaigning resumes. In: cnn.com . June 19, 2016, accessed October 19, 2018 .

- ^ MPs return to Parliament to pay tribute. In: bbc.com . June 20, 2016, accessed October 19, 2018 .

- ^ First Brexit Poll Since Jo Cox Killing Has 'Remain' in Lead. In: bloombergquint.com. June 18, 2016, accessed October 23, 2018 .

- ↑ whatukthinks.org: A Little Relief for Remain? ( Memento from June 21, 2016 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Vote Leave has tumbled even further. In: businessinsider.com . June 22, 2016, accessed October 24, 2018 .

- ↑ How did this just happen? In: cnbc.com . June 24, 2016, accessed October 21, 2018 .