European Integration

The concept of European integration stands for an “ever closer union of the European peoples” (1st recital of the preamble to the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU)). Officially, this term was first used in 1954 when the Western European Union (WEU) was founded. With the establishment of the European Union (EU) by the Maastricht Treaty in 1992 , the “process of European integration was put on a new level” (1st recital of the preamble to the Maastricht Treaty); the 2007 Lisbon Treaty marks the current state of development.

The European integration process began at the economic level , but also aimed at the level of the political system and especially at justice and home affairs policy as well as a common foreign and security policy . Common framework conditions are also being negotiated in areas such as digital policy and media policy . Sometimes the term integration is also applied to the European cultural area and cultural policy, for example in the case of the European Capital of Culture and the EUNIC .

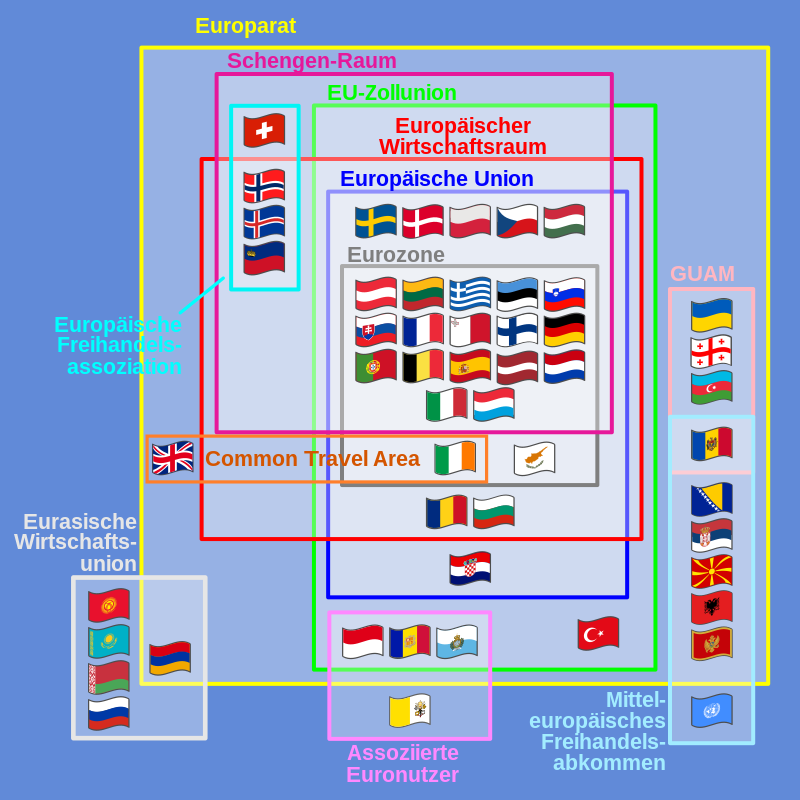

The guiding principle of European integration is not limited to the EU; because in addition to this there are a number of other international organizations in Europe , such as the Council of Europe , and most European states belong to several of them. However, the EU represents the most advanced example of regional integration , both in comparison with all other European organizations and in global comparison . The extensive transfer of national powers to European institutions has led to the European Communities , from which the EU emerged to be more than just international organizations ; the term “ supranationality ” was coined for them .

The European Union has not only advanced economic and political integration step by step in the years after its founding, it has also expanded geographically with the addition of new member states . European integration is sometimes expressly viewed as a model by international organizations on other continents; z. B. The institutional framework of the Andean Community and the African Union was modeled on the EU institutions.

The history of European integration

Timetable

|

Sign in force contract |

1948 1948 Brussels Pact |

1951 1952 Paris |

1954 1955 Paris Treaties |

1957 1958 Rome |

1965 1967 merger agreement |

1986 1987 Single European Act |

1992 1993 Maastricht |

1997 1999 Amsterdam |

2001 2003 Nice |

2007 2009 Lisbon |

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| European Communities | Three pillars of the European Union | ||||||||||||||||||||

| European Atomic Energy Community (EURATOM) | → | ← | |||||||||||||||||||

| European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) | Contract expired in 2002 | European Union (EU) | |||||||||||||||||||

| European Economic Community (EEC) | European Community (EC) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| → | Justice and Home Affairs (JI) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Police and judicial cooperation in criminal matters (PJZS) | ← | ||||||||||||||||||||

| European Political Cooperation (EPC) | → | Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) | ← | ||||||||||||||||||

| Western Union (WU) | Western European Union (WEU) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| dissolved on July 1, 2011 | |||||||||||||||||||||

Early plans for European unification

The Paneuropean movement of Richard Coudenhove-Kalergi and the efforts of the French Foreign Minister Aristide Briand in the interwar period to bring about a union of the European peoples are seen as the forerunners of European integration . The catchphrase "United States of Europe" was coined by Victor Hugo as early as 1849 and was used by Karl Kautsky ( New Time of April 28, 1911), among others, even before the First World War . It was later taken up again by politicians as diverse as Leon Trotsky and, after the Second World War, Winston Churchill in his famous Zurich speech of September 19, 1946 .

The European unification movement after the Second World War

After 1945 there were numerous different efforts to create European organizations. Until 1989, however, these efforts were overshadowed by the division of Europe by the Iron Curtain , so that the organizations that exist today were initially largely restricted to Western Europe. A first "wave" of the establishment of political, economic and military alliances covers the period from 1948 to 1960.

As a first step in economic integration, 18 Western European states that benefited from US support under the Marshall Plan founded the Organization for European Economic Cooperation (OEEC) in 1948 , through which these states participate in the decision-making process on the use of the Funds for the reconstruction of the western European states were involved. However, plans to create a large free trade area encompassing all OEEC countries failed. The OECD emerged from the OEEC in 1961 .

The first project of political cooperation is the Council of Europe , founded in 1949 under the significant influence of Winston Churchill . The Council of Europe has a wide range of tasks by virtue of its statutes (Art. 1), which in addition to advising on issues of common interest and concluding agreements includes economic, social, cultural and scientific cooperation as well as “the protection and further development of human rights and fundamental freedoms”. However, its institutional form remains - apart from the establishment of a supranational court of justice, namely the European Court of Human Rights with its seat in Strasbourg - at the level of an intergovernmental organization ( intergovernmentalism ). The European Convention on Human Rights , concluded within the framework of the Council of Europe in 1950 , with which the protection of fundamental rights in Europe was taken to a new level, is a treaty under international law between the member states. The main focus of the work of the Council of Europe today lies in the area of human rights and the promotion of democratization.

The military integration goes back to the founded in 1948, the Brussels Pact , from 1949, the NATO and 1954, the Western European Union (WEU) emerged.

In the Soviet sphere of influence, the Council for Mutual Economic Aid was founded in 1949 , and the Warsaw Pact was concluded in 1955 . These organizations were dissolved in 1990/91. Most of their former member states or the states that emerged from them are now members of the EU and NATO; With the exception of Belarus, they all belong to the Council of Europe.

The Western European Integration Approach (1951–1989)

Nucleus of today's European Union was the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC, " Coal and Steel Community "). The ECSC was based on the so-called Schuman Plan and a declaration by the French Foreign Minister Robert Schuman from May 9, 1950 and existed from 1952 to 2002. The Schuman Plan represents a further development of the French Ruhr policy. Six states - Belgium took part in the ECSC , the Federal Republic of Germany , France , Italy , Luxembourg and the Netherlands - participated. On March 25, 1957, the same states signed the Treaty of Rome , which established the European Economic Community (EEC) and the European Atomic Energy Community (Euratom). The Treaty establishing the European Economic Community came into force on January 1, 1958, and provided for the implementation of a common market within a transitional period of twelve years.

After the failure of a large (western) European free trade area under the umbrella of the OEEC, the “small” European free trade area ( EFTA ) was only created in 1960 , in which those western European states that were not members of the European Economic Community (EEC) participated.

In 1968 the last internal tariffs within the EC countries were abolished and a common customs tariff was introduced for third countries. With this the level of integration of the customs union was reached. Cooperation in the currency area began in the 1970s. The currency snake system was introduced in 1972 and the European Monetary System (EMS) in 1979 . The next important step was the Single European Act (EEA), signed in 1986 , which strengthened the organs of the EC and expanded the powers of the EC and the goals of integration with a view to creating a European internal market by 1992. In 1985, the Schengen Agreement to abolish border controls between the Member States was signed, which came into force in 1995.

Pan-European integration and the establishment of the European Union

The first pan-European, i.e. H. The organization linking the two blocs was the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe (CSCE), which met for the first time from 1973 to 1975 in Helsinki. The Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) emerged from it in 1995 , to which, however, not only all European states but also the USA and Canada as well as the Central Asian successor states of the USSR belong.

The Maastricht Treaty establishing the European Union was signed in 1992 . He raised European integration to a new level by developing the economic community into a political union . He added two new pillars to the strongest pillar of European integration, the three EC treaties: the common foreign and security policy (CFSP) and police and judicial cooperation in criminal matters . With regard to the first pillar, the establishment of an economic and monetary union was declared the central goal. The European internal market came into effect shortly after the Maastricht Treaty was signed on January 1, 1993.

After 1992, the deepening of European integration was advanced primarily through two further treaties: the 1997 Treaty of Amsterdam , which strengthened pillars two and three, the common foreign and security policy and domestic and judicial cooperation, and introduced a social charter , as well as the Treaty of Nice 2001, which was supposed to make the European Union “fit” for the EU's eastward expansion . The next important step took place on December 1, 2009 with the entry into force of the Lisbon Treaty , after the failure of the Treaty establishing a Constitution for Europe to come into force in 2005 .

A particularly important step towards integration was the introduction of the euro as a means of payment on January 1, 2002, because Europe thus proved to be directly useful and even more “tangible” for every citizen whose state is a member of the euro area , in everyday life and when staying abroad within this new common currency area “Than before - the euro had already been introduced in 1999 for cashless payment transactions.

Concepts for the future of the European integration process

For a long time, a principle of the integration process within the EC / EU has been the binding, uniform application of the acquis communautaire , i. H. the uniform application of all Community legal norms for all Member States. Originally, transitional periods until the implementation and application of Community law were only provided for new members. As the number of Member States grew, so did the differences between them, both in terms of economic and social frameworks and in terms of the political expectations and objectives of the integration process. On the one hand, this resulted in a fundamental debate about the finality of European integration, which revolves around terms such as confederation / intergovernmentalism , confederation / supranationalism and federal state or “United States of Europe”. On the other hand, since the beginning of the 1990s, various concepts for "flexibilization", ie. H. on a regulated deviation from the principle of uniformity of the acquis communautaire .

Confederation of States, Union of States, United States of Europe or European Republic

Against the background of an ever more closely connected Europe, the question arises of how far this merging should go and which competencies should be located at the European level and which at the level of the nation states. While Eurosceptics already see too many tasks in European responsibility, those in favor of Europe are in favor of a further Europeanization of the previous tasks of the EU member states. A federal state (“ United States of Europe ”, “European Republic”) is being discussed as a particularly strongly integrated model , in which the nation states or the regions that make them up are to be merged in favor of a state in the form of a new European, democratic , constitutional , federal republic . Due to the cultural, linguistic, political, media and economic heterogeneity within Europe, this model is considered to be ambitious for the foreseeable future. However, the aim of even the strongest federal models is always to maintain this diversity. They are concerned with equality of civil rights and a community based on solidarity with the preservation of this diversity, recognized as a cultural wealth worthy of protection, as it is already expressed in the motto of the European Union “United in diversity”. At the same time, linguistically and culturally diverse state structures with quite independent sub-regions such as Switzerland or the USA with their very independent member states are mentioned as possible models.

According to some experts, the European Union will remain an association of largely sovereign states for a long time to come. Due to its institutionally anchored mixed character, the Union is viewed as a structure sui generis . In its case law on the Maastricht Treaty, the Federal Constitutional Court coined the term “ union of states ” for this .

In order to counter centralization tendencies within the Union, which in some places feed the critical catchphrase of “Eurocracy”, the Union was committed to the principle of subsidiarity , according to which every task should be settled on the lowest level at which it can be carried out. The principle of subsidiarity has been an integral part of the constitutional order of the EC and EU since the Maastricht Treaty (cf. Art. 5 (3) TEU).

Core Europe

Coined in 1994 by a paper by Wolfgang Schäuble and Karl Lamers , the term core Europe describes a group of those European states that are linked to one another through the greatest possible political, economic and military integration. Specifically, this can currently be understood as the states that are also members not only of the EU, but also of the euro zone , the Schengen Agreement and NATO.

Two-speed Europe

The political and economic integration process within the European Union has shown in recent years that it is quite possible that some EU member states will take further steps, while others remain behind for the time being or only take part in further integration steps on a selective basis. A distinction must be made between voluntary progress or lagging behind by member states on the one hand and the qualification of member states for a certain integration step on the basis of contractually defined criteria on the other.

As a common currency , the euro has only been legal tender in 19 of the 27 EU member states. Of the remaining 8 countries, however, only Sweden and Denmark decided “of their own free will” not to participate in monetary union (for the time being) (“opting-out clause”), while 6 countries met the criteria of monetary stability, the prerequisite for participation are not yet fulfilled.

The Schengen Agreement for the extensive abolition of controls at common borders was signed in 1985 by Germany , France and the Benelux countries. Only gradually did other states join, including the non-EU states Norway , Switzerland and Iceland .

The 1992 Social Protocol to the Treaty on European Union was also an example of a "two-speed Europe". Here, however, the uniformity of the acquis communautaire was restored when Great Britain gave up its resistance to this step towards integration.

Increased cooperation

With the Treaty of Amsterdam , the concept of increased cooperation between groups willing to integrate EU member states in certain policy areas was for the first time permanently anchored in the EU Treaty (ex Art. 43 EU, currently Art. 20 TEU and Art. 326–334 TFEU). Certain rules apply for this, e.g. B. Cooperation must not contradict the acquis communautaire, which is binding on all member states, and it must in principle be open to all member states.

Variable geometry

Within the EU, the term variable geometry means the possibility of overlapping memberships of states in different groups of increased cooperation, each with a different composition. Analogous to this, the term also describes the overlaps between the various European organizations.

Europe à la carte

While a two-speed Europe is understood to mean a future of the EU in which further integration steps are predominantly carried out by the same group of states, the term “Europe à la carte” is used when each individual member state individually takes steps to take over from further integration steps seeks out those he likes.

Characteristics of the European integration process

Irregular course of integration

European integration has not proceeded smoothly ; rather, phases of apparently accelerated integration have alternated with phases of stagnation. There were considerable spurts in the European unification process, during which integration was strongly promoted (Sandholtz / Zysman 1989), but also phases of standstill - just think of the empty chair policy - and even threats from individual member states to leave. The European integration process did not develop according to a guideline or a specific concept; rather, phases in which the supranational dynamics of the integration process came to the fore have stood out from those which were more determined by intergovernmental constellations and thus by the difficult compromise and consensus finding between the member states. One possible explanation for this discontinuity in the integration process is information asymmetries between the governments of the member states, which decide in the context of contract negotiations on "more" or "less" of integration (Schneider / Cederman 1994).

This irregular course has also found its expression in the development of political science integration theories , which, depending on the political “economic situation ”, fluctuated between neofunctional , federal and institutional approaches in phases of accelerated integration and intergovernmental approaches in phases of stagnation.

Integration as a selective, asymmetrical process

The European integration process is based on the selection of the currently acceptable options. Although far-reaching and diverse integration steps, reform concepts or even visions have been and are being launched in each phase, there are obviously only a few and limited projects that find consensus among those involved and thus constitute the actual process.

This is one of the reasons why the European integration process presents itself as a one-sided or asymmetrical process : while the economic integration of the EU through the common internal market has reached a high level since 1993 and the introduction of the euro from 1999, one is in social policy as well as in foreign and Security issues are still far from a common policy. However, there is also no uniform model of integration, such as B. the controversial discussion about a European social model shows.

One possible explanation for this is that economic integration up to the level of the internal market is primarily based on the dismantling of trade restrictions (“negative integration”); Integration z. B. in the area of social policy, however, requires the development of common protection mechanisms ("positive integration"), which is made more difficult by the existing, very different social systems of the EU member states (Scharpf 1999). However, this explanation is unsatisfactory insofar as the European Union pursues a markedly protectionist and clearly discriminatory foreign trade policy, in which trade restrictions have also been set up (Jachtenfuchs / Kohler-Koch 1996).

Criticism of the integration process

The EU's “democratic deficit”

From a political science perspective, the EU's democratic deficit associated with the unification process is viewed critically. This criticism is directed, on the one hand, against the institutional structure of the EU itself and, on the other hand, against the loss of political control at the level of the nation states that goes along with progressive integration (cf. Graf Kielmannsegg 1996). The integration path embarked on between 2010 and 2013 with the aim of combating the euro crisis , including the fiscal pact , ESM and six-pack , has further increased the democratic deficit. It is reinforced in particular by the fact that these instruments and agreements are based on the intergovernmental method. In Germany in particular, it is currently being discussed whether the deficit can be resolved by dismantling the existing system or by expanding it completely. The British historian Steven Beller points out: "You shouldn't just break complex structures just because they have some flaws."

Further criticisms

- Elite project

- Euroscepticism in parts of the population

- dominant influence of the EU Commission (in regulatory policy)

- Deepening and expanding do not work hand in hand

- EU capacity for further accessions

- unexplained future prospects; see: EU finality debate :

See also

literature

- Altmann, Gerhard: Churchill's vision of the United States of Europe . In: European History Thematic Portal (2008)

- Bach, Maurizio, Christian Lahusen, Georg Vobruba (eds.): Europe in Motion . Edition Sigma, Berlin 2006. ISBN 978-3-89404-536-4 .

- Bieling, Hans-Jürgen / Lerch, Marika (2006): Theories of European Integration , 2nd edition (ND) VS-Verlag: Wiesbaden 2006. ISBN 978-3-531-15212-7 .

- Brasche, Ulrich: European integration. 4th completely revised edition, De Gruyter Oldenbourg, Berlin 2017, ISBN 978-3-11-049547-8 .

- Gerhard Brunn: European unification . In: Universal Library . No. 17038 . Reclam, Stuttgart 2002, ISBN 978-3-15-017038-0 .

- Casny, Peter: Future of European Integration - Truths about Europe . Verlag Kovac, Hamburg 2008. ISBN 978-3-8300-3334-9 .

- Conrad, Maximilian: Europeans and the Public Sphere: Communication without Community? ibidem-Verlag, Stuttgart 2014. ISBN 978-3-8382-6685-5 .

- Gehler, Michael: Europe: Ideas, Institutions, Association , 2nd, completely revised. and supplemented edition, Munich Olzog, 2010, ISBN 978-3-7892-8195-2 .

- Giering, Claus (1997): Europe between special purpose association and superstate. The development of political science integration theory in the process of European integration . Europa Union Verlag, Bonn 1997. ISBN 978-3-7713-0546-8 .

- Grimmel, Andreas / Jakobeit, Cord (eds.) (2009): Political Theories of European Integration - A text and textbook , Wiesbaden: VS-Verlag.

- Guérot, Ulrike : Why Europe has to become a republic !: A political utopia Dietz, Bonn 2016, ISBN 978-3-801-20479-2 .

- Graf Kielmannsegg, Peter (1996): Integration und Demokratie , in: Jachtenfuchs / Kohler-Koch (Eds.) (1996), pp. 47–71.

- Jachtenfuchs, Markus / Kohler-Koch, Beate (Eds.) (2003): European Integration , 2nd edition, Opladen: Leske + Budrich.

- Knodt, Michèle / Corcaci, Andreas (2012): European Integration. Instructions for theory-based analysis , Konstanz / Munich: UVK Verlagsgesellschaft. ISBN 978-3-8252-3361-7 .

- Christian Koller : 70 years ago: Take-off of European integration from Switzerland , in: Sozialarchiv Info 4 (2016). Pp. 12-22.

- Krüger, Peter : Ways and contradictions of European integration in the 20th century (= writings of the historical college . Lectures. Vol. 45). Historisches Kolleg Foundation, Munich 1995 ( digitized version ).

- Krüger, Peter (ed.): The European State System in Transition. Structural conditions and moving forces since the early modern period (= writings of the historical college. Colloquia. Vol. 35). Oldenbourg, Munich 1996, ISBN 3-486-56171-5 ( digitized ).

- Platzer, Hans-Wolfgang (2013): Expansion or dismantling of European integration ?. Barriers and paths to deepening democratic and social integration , international policy analysis by the Friedrich Ebert Foundation,

- Schäfer, Anton: The draft constitution for the establishment of a European Union, Outstanding Documents from 1923 to 2004 , EDITION EUROPA Verlag, ISBN 978-3-9500616-7-3 .

- Scharpf, Fritz W. (1999): Governing in Europe: effective and democratic? Frankfurt, New York: Campus.

- Schneider, Gerald / Cederman Lars-Erik (1994): The Change of Tide in Political Cooperation: A Limited Information Model of European Integration, in: International Organization 48 (4): 633-662.

- Thiemeyer, Guido: European integration. Motives - processes - structures . Böhlau-Verlag Cologne 2010 (UTB Volume 3297) ISBN 978-3-8252-3297-9 .

- Vobruba, Georg: The dynamism of Europe. Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, 2., act. Wiesbaden edition 2007. ISBN 978-3-531-15463-3 .

- Weidenfeld, Werner / Wessels, Wolfgang (eds.) (2016): Europe from A – Z. Paperback of European integration , 14th edition, Baden-Baden: Nomos, ISBN 978-3-8487-2654-7 .

- Wiener, Antje / Diez, Thomas (2009): European Integration Theory , 2nd ed., New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-922609-2 .

Web links

- Reports from the European Stability Initiative (ESI) on the subject

- Peter-Christian Müller-Graff Lecture “The mandate of the Basic Law for European Integration” on YouTube

Individual evidence

- ^ Hugo, Victor (1849): “Un jour viendra”, speech to the Paris Peace Congress on August 21, 1849, in: Discours politiques français, Stuttgart: Reclam (2002), pp. 19-22.

- ^ Trotsky, Leo (1923): "On the Topicality of the Parole 'United States of Europe'", in: Pravda, No. 144, June 30, 1923 ( German translation ).

- ↑ http://www.europa-union.de/fileadmin/files_eud/PDF-Dateien_EUD/Allg._Dokumente/Churchill_Rede_19.09.1946_D.pdf

- ^ John Gillingham: The French Ruhr Policy and the Origins of the Schuman Plan. In: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte, issue 1/1987 (PDF; 7.9 MB), ISSN 0042-5702 , p. 1 ff.

- ↑ BVerfGE 89, 155 of October 12, 1993.

- ↑ http://library.fes.de/pdf-files/id/ipa/10383.pdf

- ↑ See Steven Beller in "Historians: The fall of the Danube Monarchy was a catastrophic error" in Die Presse on November 13, 2018.

- ^ Haller, Max: European integration as an elite process. The end of a dream? Wiesbaden 2009