European Coal and Steel Community

The European Coal and Steel Community , shortly officially ECSC , often Coal and Steel Community , was named a European trade association and the oldest of the three European Communities . It gave all member states access to coal and steel without paying tariffs . A special novelty was the establishment of a high authority which was able to make common regulations for all member states in the area of the coal and steel industry , i.e. coal and steel production. The ECSC was the very first supranational organization; Initially, its supranational character (German version: “supranational” character) was expressly mentioned in Article 9 of the ECSC Treaty of April 18, 1951.

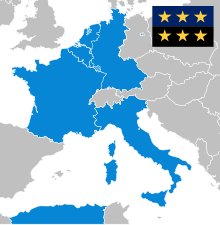

The founding states of the ECSC Treaty were Belgium , the Federal Republic of Germany , France , Italy , Luxembourg and the Netherlands . The ECSC Treaty, which was concluded for a period of 50 years, expired on July 23, 2002. It was not renewed; its regulatory matter was henceforth included in the EC Treaty , and since 2009 the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union . Since the ECSC was part of the European Communities, and later also the European Union, joining the European Communities or the European Union also meant joining the ECSC, so that when the ECSC was terminated, Denmark , Ireland , the United Kingdom , Greece , Portugal , Spain , Finland , Austria and Sweden were members.

history

The organization was founded on April 18, 1951 by the Treaty of Paris and came into force on July 23, 1952. The ECSC Treaty was based on the Schuman Plan , an initiative of the French Foreign Minister Robert Schuman , in which he made a proposal to the German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer , which he immediately approved: joint control of the member states' coal and steel industry without customs. This meant that the Ruhr area , which was then under the control of the International Ruhr Authority and British occupation and whose facilities were partially dismantled as reparations by 1949 , had a chance for new growth.

For a number of years, the coal and steel union was regarded as a “flywheel” of the economic rebuilding in West Germany . The idea of harmonizing German and French coal and steel policies, however, was not new. There have already been discussions in the OEEC about restructuring the coal and steel industries. The International Crude Steel Community of 1926/31, a cartel of German, French, Belgian and Luxembourg steel producers, had z. T. had comparable tasks.

In Schuman's argumentation, the main objective of the treaty was to secure intra-European peace through “ communitisation ”, i.e. the mutual control of the war-essential goods coal and steel, as well as the safeguarding of these production factors, which were decisive for the reconstruction after the Second World War .

The German Federal Ministry of Economics, under the aegis of Ludwig Erhard , was extremely skeptical. Erhard was not prepared to put all economic principles behind the political goals of integration. According to Nikolaus Bayer, the “main goal” that Chancellor Adenauer pursued with the coal and steel union was “a quick return of Germany as an equal member of the Western community”. In return, Adenauer was also prepared to compromise on detailed issues or to accept disadvantages. Ludolf Herbst describes the situation of the German federal government at the time with the words: "Since Bonn did not yet have national sovereignty, supranationality in itself did not mean a renunciation." Great Britain rejected the plan; it was afraid that this plan would affect its sovereignty.

In Germany itself, the Social Democratic opposition initially rejected the plan, as it would have committed the young Federal Republic to integration into the West. However, the SPD had not yet given up hope of reunification of Germany as a non-aligned or neutral state. The DGB, on the other hand, which also took part in the negotiations on the ECSC, withdrew from the SPD positions in the course of the process: they agreed to integration with the West as part of a European integration and thus achieved union participation in the institutions of the coal and steel union.

After many negotiations with the German government, Jean Monnet presented a draft treaty on June 20, 1950. The national delegations should examine the proposals first. A special committee for the Schuman Plan was set up in the Federal Cabinet. On June 29, recommendations were then passed by the federal cabinet. Against the background of international developments, the Korean War had just broken out in the Far East and because of the Dutch opposition to the powers of the High Authority, Monnet wanted to urge those involved to sign. Chancellor Adenauer asked for more time to be able to analyze the draft in peace. The federal government, in particular Minister of Economics Erhard, made it clear that Germany would only agree to this plan if controls over the Ruhr industry were abolished. In Erhard's opinion, even in normal times, a sovereign regulation of the prices for coal and steel cannot be dispensed with in the context of a freer economic policy. A compromise was finally reached on March 14, 1951, so that the ECSC Treaty could be signed on April 18, 1951.

At that time, Germany had the richest coal reserves in the six countries. France was given access to the Ruhr area, which was in the former British occupation zone and whose raw material production and economic development had until then still suffered from the sanctions of the victorious powers. Since France already had a lot of influence in the then independent Saarland , this was another opportunity to benefit from raw material deposits. In order to gain access to the German industrial areas, France demanded above all the canalization of the Moselle .

The organs of the ECSC, the European Economic Community (EEC) and the European Atomic Energy Community (EURATOM) were merged on April 8, 1965 through the so-called merger agreement . The legal independence of the three communities remained unaffected.

According to Bayer, the coal and steel union was an unprecedented supranational organization when it was founded, to which the member states voluntarily ceded parts of their sovereign rights. It thus marked the beginning of the process of European integration and had a decisive influence on the following steps. On the one hand, elements of liberal capitalism were adopted and implemented in the coal and steel union, which the USA strongly advocated, and on the other hand, the coal and steel union marks one of the first steps in Europe's emancipation from the USA. The historian Ludolf Herbst wrote in 1989 that "decisive impulses for the continuation of European integration emanated from the coal and steel union."

From around 1952, oil experienced a hitherto unimaginable boom in many areas: in 1955, the 151 million tons of coal mined in West Germany covered almost 80 percent of West German energy needs. In 1965, the West German energy consumption reached 268 million tons of hard coal units . The coal only covered 42.1 percent (113 million tons); Petroleum 41.2 percent (110.5 million tons of SCE). Oil heating displaced coal heating and diesel locomotives displaced steam locomotives in many households .

After miners' strike in Belgium at the beginning of 1959, the three Benelux countries demanded that the coal and steel union be officially declared a crisis in accordance with Article 58 of the ECSC Treaty. The other three - Germany, France and Italy - refused.

In the 1950s, France opened up large oil and gas reserves in its colony, Algeria . In the spring of 1959, the French government under Charles de Gaulle - also with reference to this - demanded a revision of the coal and steel union.

Timetable

|

Sign in force contract |

1948 1948 Brussels Pact |

1951 1952 Paris |

1954 1955 Paris Treaties |

1957 1958 Rome |

1965 1967 merger agreement |

1986 1987 Single European Act |

1992 1993 Maastricht |

1997 1999 Amsterdam |

2001 2003 Nice |

2007 2009 Lisbon |

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| European Communities | Three pillars of the European Union | ||||||||||||||||||||

| European Atomic Energy Community (EURATOM) | → | ← | |||||||||||||||||||

| European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) | Contract expired in 2002 | European Union (EU) | |||||||||||||||||||

| European Economic Community (EEC) | European Community (EC) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| → | Justice and Home Affairs (JI) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Police and judicial cooperation in criminal matters (PJZS) | ← | ||||||||||||||||||||

| European Political Cooperation (EPC) | → | Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) | ← | ||||||||||||||||||

| Western Union (WU) | Western European Union (WEU) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| dissolved on July 1, 2011 | |||||||||||||||||||||

financing

It was originally financed through the ECSC levy - in fact a tax - on coal and steel companies, which the High Authority of the ECSC benefited directly. The contractually stipulated maximum amount of this contribution was one percent. It was later discontinued. The ECSC also had the option of borrowing, which it was only allowed to use to grant loans.

organs

The organs of the community were:

- High authority : executive power with nine independent members (legislative element, merged with the European Commission in 1967 ), assisted by an advisory committee (interest representation, 51 members: employer, employee and consumer organizers, today the European Economic and Social Committee )

- Special Council of Ministers ("Council"): Ministry ministers of the individual countries (predecessor of the Council of the European Union )

- Joint Assembly ("European Parliament"): 78 members, predecessor of the European Parliament , control of the High Authority

- Court of Justice: seven members with supranational jurisdiction (judicial element, predecessor of the European Court of Justice )

- Court of Auditors: 12 members

criticism

Before signing a contract

Clarence B. Randall, a former executive of the Economic Cooperation Administration, accused the coal and steel union in a long article of "super-socialism" in the summer 1951 issue of Atlantic Monthly . The upcoming parliamentary approval of the ECSC treaties was, in his view, a move by the free market economy to the scaffold.

The Iron and Steel Industry Association (WVESI) sent a confidential circular to its members in June 1950 with an eighteen-page synopsis with a critical examination of the Schuman Declaration of May 9th. Ultimately, it saw in the planned ECSC nothing more than a “large cartel-like organization” with the aim of securing the rebuilding of French post-war industry:

“There is no doubt that Monnet's plans to build up the French economy have reached a critical stage. There is no point in expanding the iron and steel capacity of the French plants to 15 million tons if the corresponding sales market is missing. The French are always concerned about safety. He did not expect our steel production to be rebuilt quickly. A comparison of the capacities on both sides shows that we still have reserves for increasing our production. May still be missing. In this situation, the French are faced with the decision to expand their facilities or to achieve that we - no longer through political dictation, but voluntarily [...] restrict ourselves in our production.

Despite fundamental commitments regarding the same starting conditions for all industries involved, the German steelmakers believed that in the future they would no longer be able to determine [their] production as a whole and at the individual plants. In this context, the establishment of a supranational competence seemed like a specter. The emerging "extremely far-reaching decision-making power" of the President of the High Authority, as well as the statement that he would be "hardly a German", reinforced the fear of the "disastrous consequences" of a policy intended by France, the sole purpose of which was to to stop the dynamic factory modernization and to put the German smelter owners on a leash.

It is therefore of the greatest importance, when concluding the State Treaty, to bring out conditions that allow us to develop our iron and steel industry appropriately. "

Adenauer was more concerned with the political advantages of the Schuman Plan. The chances of redesigning Franco-German relations and enhancing the Federal Republic's international reputation through equality and equal treatment outweighed all other considerations.

Adenauer clearly instructed the head of the German negotiators, Walter Hallstein , not to endanger the outcome of the negotiations by any special requests from the “Ruhr captains”. That was fine with the French side. As a result of the Korean War, France was exposed to increasing pressure from the US to agree to Germany's rearmament . Monnet was very keen to conclude a contract that was ready for signature as quickly as possible. The solution to technical issues should be discussed later. Economic issues played only a subordinate role for Paris. The industry did not get the guarantees that it had specifically asked for.

Not only in Germany, but also in all other ECSC countries, the employers attacked the plan. They felt completely ignored in the formulation of the economic and institutional provisions. The High Authority was seen, among other things, as an instrument of some kind of nationalization ; the representative of Luxembourg described them on May 7, 1951 as an "administrative monster". The French branch association Chambre Syndicale de la Sidérurgie Française (CSSF) feared a "dirigismus of the worst kind."

The national branch associations only cooperated selectively in their resistance to the ECSC. The CSSF wrongly assumed that Bonn would not agree to the ECSC. When they found out the opposite, they decided, together with the Association of Luxembourg Smugglers ( GISL ), to adopt the tactic of "accepting the plan, but immediately demanding a revision of the really important points". It seemed urgent, since with the establishment of the highest Union authority, the old International Ruhr Authority would most likely disappear and the question of coal distribution, which is very important for the French and Luxembourgers with their large minette deposits , would arise from the start. The revision of the texts had to take place before the High Authority was even deployed.

Acceptance obligation

Germany's steelworks were banned from importing cheap American coal out of consideration for mining in the Ruhr. In 1965/66 US coal was 15 D-Marks per ton cheaper than Ruhr coal. Hans-Günther Sohl , WVESI chairman and general director of August Thyssen-Hütte , said that short-time work and layoffs were threatened in the steel industry. If necessary, the German steel industry would have to migrate to other EEC countries. No one can be expected to work in the red for years because of the coal.

Favor of Belgium

The High Authority raised a surcharge on Ruhrkohle and Hollandkohle, which was supposed to flow into the modernization of the Belgian mining industry in order to make it more efficient and thus more competitive. The authorities did not intervene when nothing significant happened there.

See also

literature

- Nikolaus Bayer: Roots of the European Union. Visionary realpolitik when the coal and steel union was founded. Röhrig-Verlag, Sankt Ingbert 2002, ISBN 3-86110-301-X .

- Severin Cramm: Under the sign of European integration. The DGB and the ECSC negotiations 1950/51. In: Work - Movement - History. Journal of Historical Studies . Issue II / 2016.

- Walter Obwexer : The end of the European Coal and Steel Community. In: European Journal for Business Law (EuZW), 2002, pp. 517–524.

- Heinz Potthoff: From the occupying state to the European community: Ruhr authority, coal and steel union, EEC, Euratom. Publishing house for literature and current affairs, Hanover 1964.

- Manfred Rasch, Kurt Düwell (Hrsg.): Beginnings and effects of the coal and steel union on Europe. The steel industry in politics and economy. Klartext, Essen 2007, ISBN 3-89861-806-4 .

- Hans-Jürgen Schlochauer : On the question of the legal nature of the European Coal and Steel Community. In: Walter Schätzel, Hans-Jürgen Schlochauer (Hrsg.): Legal issues of the international organization. Festschrift for Hans Wehberg on his 70th birthday. Frankfurt am Main 1956, pp. 361-373.

- Tobias Witschke: Danger to competition. The merger control of the European Coal and Steel Community and the "re-concentration" of the Ruhr steel industry 1950–1963. (= Yearbook for Economic History; Supplement 10), Akademie Verlag, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-05-004232-9 .

Web links

- Treaty establishing the European Coal and Steel Community In: EUR-Lex .

- europa.eu: Information about the expiry of the contract period

- Files of the European Coal and Steel Community can be viewed in the EU Historical Archives in Florence

- German Historical Museum : Beginnings of European Integration

- Federal Agency for Civic Education : Foreign policy context with a picture of the signing

- Federal Chancellor Willy Brandt Foundation : Photograph of the signature side of the contract with the seals of the eight signatories

- American University : Explanation of the historical background ( Memento of November 3, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) (English).

- CVCE : The Treaties Establishing the European Communities and the Treaty Establishing the ECSC

Individual evidence

- ↑ Article 9 . Treaty establishing the European Coal and Steel Community .

- ↑ a b Nikolaus Bayer: Roots of the European Union. Visionary realpolitik when the coal and steel union was founded . Röhrig-Verlag, Sankt Ingbert 2002.

- ↑ Ludolf Herbst: Option for the West. Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag , Munich 1989, p. 86.

- ^ Severin Cramm: Under the sign of European integration. The DGB and the ECSC negotiations 1950/51. In: Work - Movement - History. Journal of Historical Studies . No. 2, 2016.

- ^ Hanns Jürgen Küsters: April 18, 1951: Signing of the contract for the establishment of the European Coal and Steel Community in Paris. Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, accessed on October 12, 2012 .

- ↑ Nikolaus Bayer: Roots of the European Union. Visionary realpolitik when the coal and steel union was founded. Röhrig-Verlag, Sankt Ingbert 2002, pp. 105-109.

- ↑ Ludolf Herbst: Option for the West. Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, Munich 1989, p. 173.

- ↑ a b Ready for battle . In: Der Spiegel . No. 26 , 1966 ( online ).

- ↑ a b The end of the closed season . In: Der Spiegel . No. 9 , 1959 ( online ).

- ↑ Article 58 . Treaty establishing the European Coal and Steel Community .

- ↑ a b Somehow outdated . In: Der Spiegel . No. 22 , 1959, pp. 22nd f . ( online ).

- ↑ German Bundestag: Coal and Steel Community Treaty expires in 2002 (archive)

- ^ CVCE, European Navigator : The means of the ECSC .

- ^ Charles Barthel: Storm in a water glass. The striving of the steel makers to implement the Schuman Plan. Some considerations from the perspective of Luxembourg industrial archives (1950–1952). (PDF file, 670 kB) In: Center d'études et de recherches européennes Robert Schuman (Collectif), Le Luxembourg face à la construction européenne - Luxembourg and European unification, Luxembourg 1996. pp. 203–252 , archived from the original on December 20, 2013 ; Retrieved June 8, 2014 .

- ^ Charles Barthel: Center d'études et de recherches européennes Robert Schuman (Collectif). Le Luxembourg face à la construction européenne - Luxembourg and European unification, Luxembourg 1996, p. 1

- ^ Charles Barthel: Center d'études et de recherches européennes Robert Schuman (Collectif). Le Luxembourg face à la construction européenne - Luxembourg and European unification, Luxembourg 1996, FN 6.

- ^ Charles Barthel: Center d'études et de recherches européennes. Robert Schuman (Collectif), Le Luxembourg face à la construction européenne - Luxembourg and European unification, Luxembourg 1996, p. 4.