A lot of noise about nothing

Much Ado About Nothing ( Early Modern English Much adoe about Nothing ) is a comedy by William Shakespeare . The work is about the wedding of the Florentine nobleman Claudio with Hero, daughter of the governor of Messina. The wedding plans encounter external obstacles in the form of an intrigue of Don John, the illegitimate brother of the King of Aragon. On the other hand, Beatrice and Benedikt only admit their affection through some machinations of the other figures. The work was first mentioned in an entry in the “Stationer's Register” in August 1600. In the same year it was printed as a quarto in Valentine Simmes' workshop . The first recorded performance dates back to 1613. Most scholars believe that Shakespeare completed the play around the turn of the year 1598/99. Along with As You Like It and What will you be Much Ado About Nothing counted among the so-called romantic comedies of Shakespeare.

Overview

Storylines

The main plot describes the circumstances of the marriage of the Florentine nobleman Claudio to Hero, the daughter of Leonato, the governor of Messina. The work has two subplots. The first describes an intrigue of the Spanish nobleman Don John, who wants to thwart Claudio's marriage out of hatred for Claudio . The comic episode about the security guard Dogberry and his helpers is woven into this side thread . The second subplot describes the love between the nobleman Benedikt and Beatrice, Leonato's niece .

main characters

The stage company of the work has two main groups. The first is centered around Leonato, the governor of Messina. His country house is the scene of the action. Leonato is a widower and has only one child, his daughter Hero, who is his sole heiress. He lives with his brother Antonio and his niece Beatrice. The group around Leonato also includes Margarethe and Ursula, the court ladies of Hero, as well as the sergeant Dogberry with his entourage and the clergyman Brother Francis. The center of the second main group is the heir to the throne of the Kingdom of Aragon, Prince Don Pedro. He is accompanied by his half-brother Don John as well as the noble Benedict from Padua and Claudio from Florence. They also include the servants Conrad and Borachio and the singer Balthasar. You can immediately see the symmetry of the two groups: the brothers Leonato and Antonio from Sicily and the brothers Don Pedro and Don John from Spain. The Sicilian group includes Beatrice and Hero and the Italian group includes the prince's feudal men, the nobles Benedict and Claudio.

Narrated the time and place of the action

The work is set in the port city of Messina at the time when Sicily was under Spanish rule. This is indicated by the title of Don Pedro, Prince of Aragon. Relations between Sicily and Spain, especially the Crown of Aragon , span the rather long period between the 12th and 16th centuries. The act itself only lasts a few days and is usually moved to summer time.

action

Act I.

The play begins with the announcement that Don Pedro, the Prince of Aragon, is coming to Messina with his entourage today. While greeting the guests in the governor's residence, one of the noblemen falls in love with the host's daughter.

[Scene 1] A messenger reports to the governor of Messina that Don Pedro of Aragon is coming to the city after a successful campaign. There were few casualties in the battle, because the soldiers fought unusually bravely. Claudio in particular , a young Florentine nobleman, had been honored by the prince for his extraordinary courage in battle and is now expected by his uncle in Messina. Beatrice, the niece of Governor Leonato, asks about another participant in the campaign, a certain Benedict, whom she mocked heartily on this occasion. When the soldiers arrive, Leonato receives them at his house and invites them to stay in Messina for a month. Don Pedro accepts the invitation and introduces the host to his silent half-brother Don John , with whom he recently reconciled. Meanwhile, Beatrice and Benedikt have a violent battle of words. Both are known for not mincing words in their dealings with others and have long, if baseless, dislikes for one another. Claudio tells his comrade in arms Benedict about his love for Hero. Benedict expresses his contempt for marriage to Don Pedro and Claudio. Don Pedro offers Claudio to woo Hero in his place.

[Scene 2] Leonato and his older brother Antonio discuss the preparations for the feast to welcome the prince and his entourage. Antonio says that one of his servants overheard a conversation between the prince and Claudio , in which the prince confessed his love for Leonato's daughter Hero . The governor doubts the report and both decide to wait and see and inform Hero as a precaution .

[Scene 3] Don John, the prince's illegitimate brother, confesses to his servants Conrad and Borachio his displeasure and his willingness to show no consideration for third parties. They decide to thwart the marriage between Claudio and Hero .

Act II

[Scene 1] Leonato and Antonio with Hero and Beatrice and the maids. Entry of the masks. Don John and Borachio claim against Claudio, the Don Pedro in Hero 's in love. Claudio confesses in self-talk that he is now convinced of the prince's fraudulent intent. When Benedict enters, he confirms Claudio's impression . The prince explains to Benedict his clear and honest intentions regarding Hero. Beatrice comes to the prince with Claudio . The prince notices that Claudio is depressed. The prince reports that he kept his promise and successfully wooed Claudio for Hero . The prince makes Beatrice an offer to marry, she refuses. The prince discusses with Leonato and Claudio the preparations for the marriage between Hero and Claudio. The wedding is agreed within a week.

[Scene 2] Don John and Borachio plan the intrigue against Claudio's marriage to Hero.

Act II-V

Together with others they decide to shorten the time until their wedding by luring Benedikt and Beatrice into the love trap. Claudio, Leonato and Don Pedro let Benedikt overhear a conversation in which they discuss how much Beatrice suffers because she actually loves him. Benedict decides to have mercy on her and to return her love. Hero and her chambermaid Ursula hold a conversation with the same meaning within earshot of Beatrice, although now Benedict is the unhappy lover. She immediately decides to be kinder to Benedict from now on.

Don Juan, Don Pedro's unwanted half-brother, is planning to prevent the wedding and thus cause mischief. To prove Hero's infidelity, he stages a love scene in the window of Hero's chamber between his follower Borachio and Hero's maid Margaret, who wears Hero's clothes, and ensures that Claudio and Don Pedro observe the scene. Both fall for the spectacle and consider Hero to be unfaithful. On the following wedding day, Claudio accused her of infidelity in front of everyone present and refused to marry. Hero faints. After Claudio, Don Pedro, and Don Juan have left the church, until their honor is restored, the monk advises everyone to believe that Hero has died given the shame.

After Leonato, Hero and the monk have also left, Benedict and Beatrice, who remain alone in the church, confess their love for each other. Beatrice is convinced of Hero's innocence and makes Benedict promise to kill his friend Claudio for the damage he has caused.

But Hero's honor is restored even before the duel can take place. As it turns out, the guards who arrested the culprit Borachio and his ally Konrad on the night of don Juan's production also overheard them and thus learned of Don Juan's machinations. After hearing her testimony, Leonato is completely convinced of Hero's innocence.

Claudio feels deep remorse for the supposed death of his bride. Leonato promises to marry him off to his niece, who looks just like Hero. Of course, it turns out to be actually the living hero himself. At the wedding, Benedikt and Beatrice fall back into their old pattern of denying their mutual love with a lot of puns, until Hero and Claudio pull out some love poems that Benedikt and Beatrice wrote each other. The play ends with a happy double wedding that closes with the good news that Don Juan was arrested while fleeing Messina.

Literary templates and cultural references

In the plot about Hero and Claudio, Shakespeare takes up a narrative motif that was widespread in European Renaissance culture. Stories about a bride slandered and wrongly accused by an intrigue, her rejection by the groom, her apparent death and the subsequent happy reunion of the lovers enjoyed great popularity in the 16th century and were published in numerous epic and dramatic re-creations, including Shakespeare Time more than a dozen when there were printed versions.

Shakespeare probably knew different versions of this motif; It can be assumed with great certainty that he used both the version in Ariost's epic Orlando Furioso and the prose version in Matteo Bandello's La prima parte de le novelle as sources for the Hero-Claudio storyline. Ariost's work was published in 1516 and translated into English by John Harrington in 1591 ; in the 5th song of the epic the story of Ariodante and the Scottish princess Genevra (Ginevora) is presented, which Spenser also retells in poetry in 1590 in The Faerie Queene (II, iv). In the plot pattern of this story there are some parallels to the hero Claudio plot; Ariodante, too, is convinced of Genevra's unchastity through an intrigue and falsified evidence. Bowed down in grief, he leaves his lover and announces his suicide; in the end, however, after various entanglements, everything turned out for the better for the couple. In Bandello's novellas, published in 1554, which also provide the templates for other works by Shakespeare such as Romeo and Juliet or Twelfth Night, the 22nd story is the story of Fenicia and Timbreo, which also resembles that of Hero and Claudio in individual plot elements. In 1574, Bandello's story was translated into French in an embellished and moralized form in Belleforests Histoires tragiques ; however, Shakespeare presumably used Bandello's original version as the source.

In the development of the plot and the design of the characters, Shakespeare deviates significantly from his models in his play. In contrast to Ariost and Bandello, the intrigue and slander in Much Ado About Nothing do not come from a rival who tries in this way to destroy the existing love relationship in order to come closer to realizing his own wishes and desires. Especially in Bandello's version of the story, the central point is the classic conflict between friendship and love: the slanderous rival Girondo is a friend of the protagonist Timbreo. In contrast, Shakespeare introduces the scheming figure of the malicious outsider Don John (Don Juan), who as a Machiavellian villain out of dissatisfaction, envy or interest in power seeks to wreak havoc in order to disturb the existing order.

Shakespeare also made another significant change to his sources in his conception of Prince Don Pedro, who was a friend of Claudio, as the highest social authority. In Bandello's version of the story, the marriage is mediated by an anonymous third party; Unlike in Shakespeare's play, in which the subject of representative advertising plays a conspicuous role, the King Don Pierro of Aragon is neither privy to the marriage intentions nor involved in the staging of the advertising game. Nor is there a misunderstanding that the prince himself fell in love with the bride. In the later slander scene, Don Pedro surprisingly sees no reason to have the allegations against Hero checked and refuses to stand up for Hero, regardless of his social obligation as a prince to clarify the matter.

In addition, the rather melodramatic plot about Hero and Claudio is supplemented by the popular love fight between Beatrice and Benedick (Benedikt), which with its numerous witty word and joke battles partially pushes the actual starting plot into the background. There is no direct template or source for this storyline; In addition to the motif of "merry war", which goes back to antiquity, Shakespeare here especially takes up the convention of "mocking lovers", which was shaped in the euphuistic novels and dramas by John Lylys and by Shakespeare already with the characters by Biron and Rosaline was recorded in Love's Labor's Lost and further developed.

In Shakespeare's comedy, the changed role of the prince is again of importance for the dramaturgical connection of the storylines around the two lovers; Through his initiative and active participation in the two love intrigues, Don Pedro contributes to the fact that on the one hand the love relationship between Hero and Claudio leads to the marriage, while on the other hand the love between Beatrice and Benedick begins to develop through the double eavesdropping trick he has planned. At the same time, Don Pedro's comedic intrigue is juxtaposed with the destructive plot of his half-brother Don John; Immediately after Don Pedro announced his intention to use a trick to bring Benedick and Beatrice together (II.1), Don John and Borachio are planning his intrigue against Hero (II.2).

Shakespeare also contrasts the storylines played in the courtly milieu on a lower social level with the foolish play of the dumb bailiff Dogberry (crab apple) and Verges (slough), for which there are no direct sources. In this way, not only does the playful character of the play remain consistently even in the phases of rather threatening entanglements, but the templates used by Shakespeare are also significantly expanded in social, moral and emotional terms.

Dating

In contrast to many other works by Shakespeare, the period in which Much Ado about Nothing was created can be narrowed down with great certainty and accuracy. The piece is not listed in Francis Meres ' Palladis Tamina, which was registered for print in the Stationers' Register on September 7, 1598 and contains a list of the works of Shakespeare known up to that point in time. First evidence of the writing of the work can be found in an early note in the Stationers' Register of August 4, 1600, in which, along with other works by Shakespeare such as As you Like It and Henry V and Jonson's Every Man in His Humor , “The comedie of muche A doo about nothinge | A booke ... to be staied ”is mentioned, possibly in order to make a pirated print shortly before the legitimate first print more difficult with this blocking entry. However, a further detail in the printed edition of the piece published shortly afterwards enables an even more precise definition of the writing period for Much Ado About Nothing. In some places, for example in 4.2, instead of specifying the dramatic character of the Bottleneck, the name of Will Kemp , one of the more well-known comedic actors in the acting troupe of the Lord Chamberlain's Men , is mentioned in the text assignments of the first print early performances for this role of the simple-minded bailiff was provided by Shakespeare himself. On the basis of further contemporary evidence, however, it is clearly proven that Kemp left Shakespeare's drama company by February 11, 1599 at the latest, probably as early as late 1598 or early 1599, as other sources suggest. Much Ado about Nothing must therefore have been written in the period between late summer 1598 and the beginning of 1599. Stylistic and thematic comparative analyzes also suggest a drafting period towards the end of 1598 or beginning of 1599.

Text history

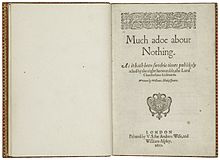

After the official entry in the Stationers' Register on August 23, 1600 for printing, the first printed version of Much Ado about Nothing appeared in the same year as a carefully set edition in four-high format (Q). The title page of this first edition contains a reference to various previous performances by the Shakespeare company: “Much adoe about | Nothing. | As it has been sundrie times publikely | acted by the right honorable, the Lord | Chamberlaine his seruants. | Written by William Shakespeare. | LONDON | Printed by VS for Andrew Wise, and | William Aspley. | 1600. “The initials VS stand for the London printer Valentine Simmes, who was also responsible for printing the first four-quarto (Q 1) for Hamlet in 1603. The first four-high edition of Much Ado about Nothing is generally regarded as a reliable text; Contrary to earlier assumptions, today's editors of the play almost unanimously assume that this print was based on an autograph manuscript by Shakespeare. Various indications such as individual discrepancies in the names and nominations of the characters or the occasional lack of stage directions point to a draft manuscript ( “foul paper” ) by Shakespeare as the master copy; in a fair copy or theater transcript as a direct book ("prompt book"), such minor errors would most likely have already been corrected.

The first folio edition from 1623 (F) was printed on the basis of the four-high printing (Q). While the four-high edition has no division into acts or scenes, the folio print contains a division into five acts; In some places individual corrections were made in minor details, presumably with the help of a director's book. In today's Shakespeare research, this print version from 1623 in folio format is mostly no longer recognized as an independent text authority. A division of the piece into 17 scenes was first made by Edward Capell in his edition of the works of Shakespeare 1767–1768; Subsequent editors generally adopted Capell's scene classification, which has only been partially changed in more recent text editions or stage versions.

Adaptations

The opera Béatrice et Bénédict is a musical adaptation of the subject matter by Hector Berlioz and was premiered in 1862. There are numerous film adaptations. In 1958, the SFB Much Ado About Nothing was created under the direction of Ludwig Berger . The DEFA filmed the piece in 1964 with Christel Bodenstein and Rolf Ludwig , directed by Martin Hellberg . In 1973 the Soviet film Much Ado About Nothing ( Mnogo shuma iz nichego ) was released, directed by Samson Iossifowitsch Samsonow . The 1993 version by Kenneth Branagh achieved the greatest success with the public . In 2011, Joss Whedon shot an adaptation of the piece . Angela Carter's novel As We Like It references Shakespeare's plays in a variety of ways.

Text output

- Total expenditure

- John Jowett, William Montgomery, Gary Taylor, and Stanley Wells (Eds.): The Oxford Shakespeare. The Complete Works. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2005, ISBN 978-0-199-267-187 .

- Jonathan Bate , Eric Rasmussen (Eds.): William Shakespeare Complete Works ( The RSC Shakespeare ). Macmillan Publishers 2008, ISBN 978-0-230-20095-1 .

- English

- Much Ado About Nothing ( The Arden Shakespeare. Third Series ). Edited by Claire McEachern. Bloomsbury, London 2006, ISBN 1-903436-83-4 .

- Much Ado About Nothing ( The Oxford Shakespeare ). Edited by Sheldon P. Zitner. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2008, ISBN 978-0-19-953611-5 .

- German

- Much ado about nothing. In: Shakespeare's Dramatic Works. Translated by August Wilhelm von Schlegel , supplemented and explained by Ludwig Tieck . Third part. G. Reimer, Berlin 1830, pp. 261-338.

- Much Ado About Nothing. Much ado about nothing ( English-German study edition ). Edited and commented by Norbert Greiner . Stauffenburg, Tübingen 1988, ISBN 3-86057-548-1 .

- Much Ado About Nothing. A lot of noise about nothing. English German. Translated and commented by Holger Michael Klein. Reclam, Ditzingen 1993, ISBN 3-15-003727-1 .

- A lot of noise about nothing. Bilingual edition. Newly translated by Frank Günther. dtv, Munich 2012, ISBN 978-3-423-12754-7 .

literature

- Hans-Dieter Gelfert : William Shakespeare in his time. Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-65919-5 , pp. 305-308.

- Stephen Greenblatt : Negotiations with Shakespeare. Clarendon, Oxford 1990, ISBN 3-596-11001-7 .

- Manfred Pfister: Much Ado About Nothing (Much Ado About Nothing). In: Ina Schabert (Ed.): Shakespeare-Handbuch. Time, man, work, posterity. Fifth, revised and supplemented edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , pp. 416-421.

- Wolfgang Riehle : Much Ado About Nothing. In: Interpretations of Shakespeare's Dramas. Philipp Reclam jun. Verlag, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-15-017513-5 , pp. 156-182.

- Ulrich Suerbaum : The Shakespeare Guide. Reclam, Ditzingen 2006, ISBN 3-15-017663-8 ; third, rev. Edition 2015, ISBN 978-3-15-020395-8 , pp. 137–145.

- Stanley Wells, Gary Taylor: William Shakespeare: A Textual Companion. Oxford University Press, Oxford 1987, ISBN 0-393-31667-X , pp. 371-374.

Web links

- 1st Quarto 1600 in the British Library , Shakespeare in Quartos.

- Much Ado About Nothing , German translation by Wolf Graf von Baudissin in the Gutenberg-DE project .

Individual evidence

- ↑ William Shakespeare: Much Ado About Nothing. Bilingual edition. German by Frank Günther, 5th edition, Munich 2012. I, 1, 1–88.

- ↑ William Shakespeare: Much Ado About Nothing. Bilingual edition. German by Frank Günther, 5th edition, Munich 2012. I, 1, 89–104 and 138–150.

- ↑ William Shakespeare: Much Ado About Nothing. Bilingual edition. German by Frank Günther, 5th edition, Munich 2012. I, 1, 105–137.

- ↑ William Shakespeare: Much Ado About Nothing. Bilingual edition. German by Frank Günther, 5th edition, Munich 2012. I, 1, 151–188.

- ↑ William Shakespeare: Much Ado About Nothing. Bilingual edition. German by Frank Günther, 5th edition, Munich 2012. I, 1, 189–265.

- ↑ William Shakespeare: Much Ado About Nothing. Bilingual edition. German by Frank Günther, 5th edition, Munich 2012. I, 1, 266–305.

- ↑ William Shakespeare: Much Ado About Nothing. Bilingual edition. German by Frank Günther, 5th edition, Munich 2012. I, 2, 1–26.

- ↑ William Shakespeare: Much Ado About Nothing. Bilingual edition. German by Frank Günther, 5th edition, Munich 2012. I, 3, 1–68.

- ↑ William Shakespeare: Much Ado About Nothing. Bilingual edition. German by Frank Günther, 5th edition, Munich 2012. II, 1, 1–73.

- ↑ William Shakespeare: Much Ado About Nothing. Bilingual edition. German by Frank Günther, 5th edition, Munich 2012. II, 1, 74–140.

- ↑ William Shakespeare: Much Ado About Nothing. Bilingual edition. German by Frank Günther, 5th edition, Munich 2012. II, 1, 141–156.

- ↑ William Shakespeare: Much Ado About Nothing. Bilingual edition. German by Frank Günther, 5th edition, Munich 2012. II, 1, 157–192.

- ↑ William Shakespeare: Much Ado About Nothing. Bilingual edition. German by Frank Günther, 5th edition, Munich 2012. II, 1, 193–239.

- ↑ William Shakespeare: Much Ado About Nothing. Bilingual edition. German by Frank Günther, 5th edition, Munich 2012. II, 1, 240–313.

- ↑ William Shakespeare: Much Ado About Nothing. Bilingual edition. German by Frank Günther, 5th edition, Munich 2012. II, 1, 314–356.

- ↑ William Shakespeare: Much Ado About Nothing. Bilingual edition. German by Frank Günther, 5th edition, Munich 2012. II, 2, 1-51.

- ↑ See William Shakespeare: Much Ado About Nothing. Edited by Sheldon P. Zitner. Oxford World Classics 2008, p. 6ff. See also Stanley Wells, Gary Taylor: William Shakespeare: A Textual Companion. Oxford University Press, Oxford 1987, ISBN 0-393-31667-X , p. 371, and Ina Schabert (ed.): Shakespeare Handbuch. 5th, revised and supplemented edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, p. 417f., And Ulrich Suerbaum: The Shakespeare Guide. 3rd, rev. Edition. Reclam, Ditzingen 2015, p. 140.

- ↑ See William Shakespeare: Much Ado About Nothing. Edited by Sheldon P. Zitner. Oxford World Classics 2008, p. 6ff. See also Stanley Wells, Gary Taylor: William Shakespeare: A Textual Companion. Oxford University Press, Oxford 1987, ISBN 0-393-31667-X , p. 371. See also Ina Schabert (Ed.): Shakespeare Handbuch. 5th, revised and supplemented edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, p. 417f., And Ulrich Suerbaum: The Shakespeare Guide. 3rd, rev. Edition. Reclam, Ditzingen 2015, p. 140. In contrast to Sheldon P. Zitner, Jonathan Bate and Eric Rassmussen, the editors of the edition of the Royal Shakespeare Company, assume that Shakespeare was more likely to have known the French translation of the Histoires tragiques by Pierre Belleforest . See Jonathan Bate, Eric Rasmussen (Eds.): William Shakespeare Complete Works. Macmillan Publishers 2008, ISBN 978-0-230-20095-1 , p. 257.

- ↑ Cf. Ina Schabert (Ed.): Shakespeare Handbook. 5th, revised and supplemented edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, p. 417f. See also William Shakespeare: Much Ado About Nothing. Edited by Sheldon P. Zitner. Oxford World Classics 2008, p. 38ff. and Hans-Dieter Gelfert: William Shakespeare in his time. Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-65919-5 , pp. 305ff. See also Wolfgang Riehle: Much Ado About Nothing. In: Interpretations of Shakespeare's Dramas. Philipp Reclam jun. Verlag, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-15-017513-5 , p. 159.

- ↑ See Wolfgang Riehle: Much Ado About Nothing. In: Interpretations of Shakespeare's Dramas. Philipp Reclam jun. Verlag, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-15-017513-5 , pp. 161ff.

- ↑ Cf. Ina Schabert (Ed.): Shakespeare Handbook. 5th, revised and supplemented edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, p. 417f. See also Hans-Dieter Gelfert: William Shakespeare in his time. Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-65919-5 , pp. 305ff. See also Wolfgang Riehle: Much Ado About Nothing. In: Interpretations of Shakespeare's Dramas. Philipp Reclam jun. Verlag, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-15-017513-5 , p. 157, and Jonathan Bate, Eric Rasmussen (Ed.): William Shakespeare Complete Works. Macmillan Publishers 2008, ISBN 978-0-230-20095-1 , p. 257.

- ^ Wolfgang Riehle: Much Ado About Nothing. In: Interpretations of Shakespeare's Dramas. Philipp Reclam jun. Verlag, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-15-017513-5 , pp. 166f.

- ↑ Cf. Ina Schabert (Ed.): Shakespeare Handbook. 5th, revised and supplemented edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, p. 417f. See also Hans-Dieter Gelfert: William Shakespeare in his time. Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-65919-5 , pp. 305ff. and Wolfgang Riehle: Much Ado About Nothing. In: Interpretations of Shakespeare's Dramas. Philipp Reclam jun. Verlag, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-15-017513-5 , pp. 176ff.

- ↑ See William Shakespeare: Much Ado About Nothing. Edited by Sheldon P. Zitner. Oxford World Classics 2008, p. 5f. and The Oxford Shakespeare . Edited by Stanley Wells and Gary Taylor . Clarendon Press, Second Edition Oxford 2005, ISBN 0-19-926718-9 , p. 569. See also Stanley Wells, Gary Taylor: William Shakespeare: A Textual Companion. Oxford University Press, Oxford 1987, ISBN 0-393-31667-X , p. 371, and Ina Schabert (ed.): Shakespeare Handbuch. 5th, revised and supplemented edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, p. 416f. and Ulrich Suerbaum: The Shakespeare Guide. 3rd, rev. Edition. Reclam, Ditzingen 2015, p. 139.

- ↑ See William Shakespeare: Much Ado About Nothing. Edited by Sheldon P. Zitner. Oxford World Classics 2008, pp. 50ff., 79ff. and 86f. and Stanley Wells, Gary Taylor: William Shakespeare: A Textual Companion. Oxford University Press, Oxford 1987, ISBN 0-393-31667-X , p. 371. Cf. also Ina Schabert (Ed.): Shakespeare Handbuch. 5th, revised and supplemented edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, p. 416f. and Ulrich Suerbaum: The Shakespeare Guide. 3rd, rev. Edition Reclam, Ditzingen 2015, pp. 140f.

- ↑ See more detailed William Shakespeare: Much Ado About Nothing. Edited by Sheldon P. Zitner. Oxford World Classics 2008, p. 50ff.