Shahrud (string instrument)

Shahrud , Persian شاهرود, DMG šāh-rūd , also šāh-i rūd , is a historical stringed instrument that is known only from drawings in two manuscripts of the music-theoretical work Kitāb al-Mūsīqā al-kabīr by the scholar al-Fārābī (around 870-950) from Central Asia and probably one of the narrative sounds . The šāh-rūd was introduced in Samarkand in the early 10th century and spread throughout the Arabic music of the Middle East.

etymology

The Persian word šāh-rūd consists of šāh , "king" ( Shah ) and rūd , which, like tār, contains the basic meaning "string". Rūd is a historical oriental lute instrument , while the long-necked lute tār is still played in Iranian music today. The Persian musician Abd al-Qadir (Ibn Ghaybi; † 1435) from Maragha in northwestern Iran mentioned the sounds rūd chātī (also rūd chānī ) next to rūdak and rūḍa . Two centuries later, the Ottoman travel writer Evliya Çelebi (1611 - after 1683) described the lute rūḍa as similar to čahārtār , a four- stringed instrument by name. The Arab historian al-Maqqari (around 1577-1632) refers to a source from the 13th century, according to which the rūḍa was found in Andalusia .

The šāh-rūd , "the king of the lute", possibly gave its name to the north Indian cupped lute sarod, which was developed in the 1860s from the Afghan rubāb . However, the Persian word sarod has been used in several spelling variants for lute instruments for much longer and generally stands for "music". In Baluchistan , the Indian sarinda- like strokes surod and sorud are known. A string instrument called şehrud during the Ottoman period , which often appears in Ottoman and Persian miniature paintings as an oversized, bulbous variant of the short-necked lute ʿūd , is named but obviously not related to the medieval šāh-rūd .

Design

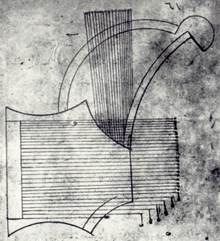

One published account of the šāh-rūd comes from a 13th century manuscript that is kept in the National Library in Cairo, the only other from a manuscript presumably dating back to the 12th century, which is in the Biblioteca Nacional in Madrid. The Madrid representation is more closely surrounded by writing, less carefully and without compasses; there is no structural difference between the two. The Cairo drawing, on the other hand, is carefully constructed with a compass and ruler. It is unclear whether both drawings are based on the same or a different template, or whether the later Cairo drawing was copied from the earlier one in Madrid. From archaeologically excavated clay figures, Sassanid rock reliefs or Persian book paintings, a rough idea of the appearance of historical musical instruments can often be gained, only the number of strings is usually adapted to the artistic requirements and is seldom realistic. This also applies to the generally more reliable representations in musicological works. The ornamental decorations of an angular harp ( čang ) on a drawing from the 13th century belong more to artistic freedom than to its actual appearance. Often harps are depicted entirely without strings or with strings leading beyond the body into the void. Sometimes the musician might not be able to hold his instrument as shown or he might not be able to grip the strings.

In the illustration of the šāh-rūd , the parallel strings run across the ceiling like a box zither, but end somewhere outside on the right side. The six shorter (highest) strings are kinked at their ends. A second bundle of strings leading upwards at right angles is enclosed by a curved wooden frame, reminiscent of the yokes of a lyre or the frame of a harp . These strings also end outside of the construction. One explanation for why both string systems protrude beyond the instrument could be that the draftsman continued to draw the string ends, which were long hanging down after their point of fixation and which were often attached with an appendage and left for decoration, as a straight line. The Madrid instrument has 40 strings, 27 of which run across the closed body and 13 at right angles to the frame, the drawing from Cairo shows a šāh-rūd with 48 strings, 29 strings over the body and 19 to the frame.

The musicologist and orientalist Rodolphe d'Erlanger (1872-1932), whose six-volume edition La musique arabe contains a translation of al-Fārābīs Kitāb al-Mūsīqā al-kabīr , classified the šāh-rūd in 1935 as a zither. Henry George Farmer (1882-1965) previously called it in 1929 in A History of Arabian Music an "arch lute or zither" and added that it was "at the beginning of the 15th century certainly an arch lute" with twice the length of a lute. Influenced by d'Erlanger, others wanted to see a harp or a psaltery , which is why Farmer in The Sources of Arabian Music (1940) turned it into a "harp psaltery". In the first edition of the Encyclopaedia of Islam from 1934 Farmer had mentioned the šāh-rūd in the article ʿŪd , that is, in the case of the oriental lute instruments. This Farmers section was carried over unchanged in the 2000 reissue, as Farmer had later reverted to his original conception. Accordingly, should one string bundle as melody strings above a fingerboard and the other strings bundle as leading to separate vertebrae drone strings are presented. This view is reinforced by al-Fārābī, who distinguished this particular instrument from the angle harps (Persian čang , Arabic ǧank ) and from the lyres (Arabic miʿzafa ) that were widespread at the time . Pavel Kurfürst followed Farmer's interpretation as the "Harp Psaltery". The Kanun player and music historian George Dimitri Sawa, on the other hand, speaks of a zither. Al-Fārābī gave a pitch range of four octaves in the 10th century . According to Abd al-Qadir, the šāh-rūd had ten double strings in the 15th century and was twice as long as the ʿūd .

In addition to the two representations of the Kitāb al-Mūsīqā , a differently drawn šāh-rūd is shown in the incunabulum from 1474 of the work Quaestiones in librum II. Sententiarum written by Johannes Duns Scotus . The incunabula is kept in the Ethnographic Museum in Brno in the Czech Republic and is believed to have originated in Brno. The stringed instrument, depicted as a colored pen drawing in a border trim between plant ornaments, is held in the hand of a standing musician. This instrument with a different body shape, but also, as in the Arabic manuscripts, with partially inwardly curved edges and without sound holes, is shown in perspective in the playing position and thus allows its size to be estimated. The number of strings remains unclear here, since only as many strings were drawn in parallel as was possible with the 25 millimeter long illustration. In the Arabic drawings the body has six edges, in the Brno representation there is one more, which, however, can be attributed to an inaccuracy. Judging by the color scheme, it would have been possible to cover the top with animal skin ( parchment ).

distribution

The šāh-rūd goes back to a musician by the name of Ḫulaiṣ ibn al-Aḥwa genannt (also called Ḥakīm ibn Aḥwaṣ al-Suġdī) who introduced this instrument to Samarkand in 918/19 and traveled with him in Sogdia in Central Asia. It later spread to Iraq, Syria and Egypt. According to the Kitāb al-Mūsīqā al-kabīr, Arabic instrumental music seems to have changed considerably around this time. Until 9/10 In the 19th century, the slim, solid form of the barbaṭ had developed into the now known form of the short-necked lute with a round body made of chips, which has since been the most popular Arabic string instrument under the name ʿūd . Tuhfat al-ʿūd was a lute half the size of the ʿūd. The “perfect lute” ( ʿūd kāmil ) with five double strings was the standard.

During the reign of the Abbasid there was, as stated by al-Fārābī, two long-necked lutes, the older ṭunbūr al-Mizani (also ṭunbūr al-Baghdādī ) and the ṭunbūr al-churasānī , both according to their areas of distribution Baghdad and Khorasan named. In addition, there were the rarer stringed instruments with plucked strings without shortening, of which the lyre ( miʿzafa ) was used more often than the harp ( ǧank ) and the trapeze zither ( qānūn ). Singers accompanied themselves on lute instruments; there is no known description of a singer playing a lyre or harp himself.

The šāh-rūd is documented until the 15th century. Its existence can no longer be proven for the 16th century. A similarly complicated string instrument is an ore lute made by Wendelin Tieffenbrucker with parallel strings attached to the sides of a harp-like frame. This extraordinary one-off piece, manufactured at the latest in 1590, had a range of 6.5 octaves and could be the successor of the šāh-rūd , which the lute maker Tieffenbrucker may have known.

literature

- Al-Farabi : Kitāb al-Mūsīqi al-Kabīr. Translated into Persian by A. Azarnush, Teheran 1996, p. 55.

- Henry George Farmer : Islam. ( Heinrich Besseler , Max Schneider (Hrsg.): Music history in pictures. Volume III. Music of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Delivery 2). Deutscher Verlag für Musik, Leipzig 1966, pp. 96, 116.

- Henry George Farmer: A History of Arabian Music to the XIIIth Century . Luzac, London 1973, p. 154, p. 209; archive.org (1st edition: 1929).

- Henry George Farmer: ʿŪd. In: The Encyclopaedia of Islam. New Edition . Volume 10. Brill, Leiden 2000, p. 769.

- Pavel Elector: The Šáh-rúd. In: Archives for Musicology . 41st year, volume 4. Steiner, Stuttgart 1984, pp. 295-308.

Individual evidence

- ↑ reproduced in: Farmer: Islam. Music history in pictures , p. 97

- ^ Farmer: The Encyclopaedia of Islam , p. 769

- ^ Adrian McNeil: Inventing the Sarod: A Cultural History . Seagull Books , London 2004, p. 27, ISBN 978-81-7046-213-2

- ↑ Şehrud. ( Memento from February 2, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Turkish music portal

- ↑ reproduced as a frontispiece in Farmer: A History of Arabian Music .

- ↑ Elector, p. 299

- ^ Farmer: Islam. Music history in pictures . P. 96

- ↑ Elector, p. 306

- ^ George Dimitri Sawa: Classification of Musical Instruments in the Medieval Middle East . In: Virginia Danielson, Scott Marius, Dwight Reynolds (Eds.): The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music. Volume 6: The Middle East. Routledge, New York / London 2002, p. 395

- ↑ Ellen Hickmann: Musica instrumentalis. Studies on the classification of musical instruments in the Middle Ages. (Collection of musicological treatises. Volume 55) Valentin Koerner, Baden-Baden 1971, p. 61

- ^ Farmer: Islam. Music history in pictures , p. 116

- ↑ Kurfürst, pp. 301-303

- ↑ George Dimitri Sawa: Music Performance Practice in the Early Abbāsid Era 132-320 AH / 750-932 AD. The Institute of Mediaeval Music, Ottawa 2004, pp. 149-151

- ^ Farmer: A History of Arabian Music , 155

- ↑ Elector, p. 308