Afghan music

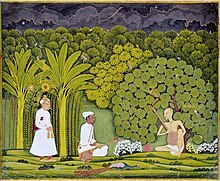

The Afghan music is deeply rooted in the Iranian cultural sphere music , and from the advent of Islam the music in eastern Iran ( Khorasan independently evolved) and from there to the Persian culture in Central Asia to Northern India in the Muslim belt by various Persian and perserisierte dynasties ( Ghorids , Ghaznavids , Mamluks , Saffarids , Samanids , Kurt dynasty ...) and by Persian scholars, poets, mystics and musicians spread (also Indo-Iranian culture called). Some of these musical styles included the Ghazel and the Persian Kasside . The Hindu Shahi and Kabulshahan dynasties from the early Middle Ages to the 10th century and, in modern times, the Persian-speaking Mughals - from Babur to Akbar - promoted music, dance and song as well as poetry. Kabul was a center or capital of the two dynasties. Agra and Delhi (fa: city of the heart) were important cities and permanent residences of the Mughal Empire . Babur's tomb is located in the Baburgarten in Kabul. In addition, today's soil in the country was the center of Zoroastrianism and one of the major centers of Buddhism . Last but not least, the Silk Road ran through the area.

Disambiguation

Afghan music includes all music and musical instruments of this multiethnic state that originated on the soil of today's Afghanistan from antiquity to the late Middle Ages and not the music of the "Afghans", whose name has always been a synonym for the Pashtuns and basically nothing but that strongly reflecting the country's influential Persian-Chorasan music. The strength of this culture and especially its music lies in the linguistic, ethno-cultural, denominational and religious diversity of the country. A number of Greek- Bactrian , Oriental and (Indo) Iranian musical instruments, which were also made outside the border of present-day Afghanistan, which is recognized by the national state, have been among the musical instruments of this area for centuries as well as in Europe. Nevertheless: It is characteristic of the construction of typical musical instruments in Afghanistan that the materials came from natural products such as wood, fur, precious stones and pieces of ivory, such as the tanbur (a predecessor of the dutar ) or the shahnai , tabla and sarod .

Urban music of Kabul

The classical music ( Persian-Khorasanisch ) of Afghanistan consists of instrumental and vocal ragas , as well as tarana and ghazals . This reveals a historical connection between North Indian and Central Asian music, which was created, among other things, through close contact between the Ustads (fa: masters ) from Afghanistan and the respective Indian masters of music in the 20th century.

Unlike the Indian ragas, the ragas (Iran including in the eastern provinces) but are distinguished in Central Asia in general by a faster rhythm and are mostly from the tabla or the local zerbaghali , Dayra , Dhol - all percussive instruments - or Long-necked lutes such as tar , yaktar , "instrument with one string", dutar , "instrument with two strings", setar "instrument with three strings", but accompanied by four strings, sarangi and the sitar .

The typical classical instruments of Afghanistan include a. the Dutar, Surnay , Sitar , Dilruba , Tambur , ghaychak or Ghaychak. Mohamed Hussein Sarahang is considered one of the most famous interpreters of this direction.

The city of Kabul and the area south of the Hindu Kush (mountains of the Hindus) or Hundukuh (mountain of the Hindu) - once called Kabulistan - which can look back on 3000 years of history, was from the 7th century AD to the 10th century Century center of the Hindu-Buddhist dynasties of the Kabulshahan and Hindushahi . Music, dance and singing were and are integral parts of the religious meditation of Hinduism .

In the old town of Kabul there is the artist and musician quarter Charabat with the meaning "tavern", "tavern" and "meditation center", whose patrons are the Indian poets of the Persian language Amir Chosrau and Bedel Delhawi (1642-1720). To praise God and to become one with God, according to the Sufi poets, man does not need a medium or an intermediary for this.

Great and famous music masters, especially from the Tajik people, as well as local (music) historians from Afghanistan and Iran are even of the opinion that the classical, as well as Ghazel and the like. The music of Afghanistan forms the old musical culture of Khorasan and these are still structured like the hymns of the Avesta .

Thus, but also with the help of the poems and aphorisms of the Sufis such as Sanai, Rumi , Hafis , Saadi and through their Persian and Turkish colleagues from India such as the above-mentioned poets. Thanks to the Charabat district, folk music could be professionalized and the typical musical instruments in Afghanistan rebuilt, as there are many music workshops in the area around Charabat. Sarahang was in charge of Charabat .

Famous musicians of Charabat

- Nawab ( Sitarjo ), father of Qasem Jo

- Qorban Ali Khan , teacher of Qasem Jo

- Qasem Jo (1878–1957), "father of modern Afghan music"

- Ghulam Hossein (1876–1967), father of Ustad Mohamed Hussein Sarahang

- Mohammad Omar (1905–1980), rub player

- Ghulam Dastgir Shaida , singer of the poems of Saadi and Hafiz

- Amir Mohammad (1931–1997), singer of Persian poetry and rubab player

- Mohammad Hashem Cheshti (unknown – 1994), singer, teacher and player of many Afghan musical instruments

- Rahim Baksh (around 1921–2001), Ghazal singer and leader of Charabat

- Mohamed Hussein Sarahang (1924–1983), leader of Charabat, interpreter of Indian Dari poetry and member of the Gharana of Patiala .

- Abdul Ahmad Hamahang (1936–2012), singer of the song Kabul Jan

Living charabat musicians

- Sultan Ahmad Hamahang (* 1967) belongs to the current generation of Charabat

Between Charabat and Europe

- Ustad Zaland (1930 or 1935–2009)

- Mohammad Hossein Arman (* 1935 or 1936)

Descendants in exile

During the war years, some of the Charabat musicians emigrated mainly to Pakistan and Iran. A small number of them found a new home in European countries and in the USA. After the end of direct Taliban rule, Charabat singers were among the first to return to their homeland and contribute to the reconstruction of local music.

Ambiguity of the word Sâzenda

In Afghanistan, the professional musicians were also referred to as sâzenda ( Persian سازننده) designated. Saz (ساز) means music and (زننده) senda means "who is alive". Put together it means "who lives from music".

The word sazenda is the subject of the verb (ساختن) "Make, build, construct" and all its inflections ; the nouns and adjectives are derived from the imperative sâz (ساز) from. So means (سازننده) both “doer” or “designer” as well as “constructive”.

Religious music

The concept of this music is closely related to instrumental performances, although the Koran recitation is an important type of unaccompanied religious performance - as is the ecstatic Zikr ritual of the Sufis . The songs are called Naa'd . Shiite individuals and groups also sing the silent Mursia , the Manqasat , Nowheh and Rowzeh . However, the Chishti Sufi sects of Kabul are an exception in that they play instruments such as the rubab, tabla, and harmonium. This music is called Ghezâ-ye Roh (food of the soul).

Folk music

There are no grades. The music is mostly unanimous. The rhythm in the form of two to four bars plays an important role. That is why a percussion instrument, dhol or string instrument, is essential. The strings are not only torn with fingers or picks , but rather struck. The melody is often subordinated to the rhythm. Melody sequences are repeated and slightly changed. Voice and body language, facial expressions and gestures are not only used in dance. Improvisation is common during singing and playing.

At celebrations such as weddings, at birth or initiation, especially in the villages, musicians play Schalmei , Ghichak and Dhol Yaktâr or Dohl Dutâr (one-sided drum or double-sided drum), zerbaghali and flute (pers.tula) or nay , when the wedding guests accompany the bride from her parents' house to the husband's house.

The folk music of all peoples or ethnic groups living in Afghanistan and the TV appearances of the singers only got an upswing after 1978, when the People's Democratic Party came to power in Afghanistan. Musicians from different parts of the country were presented on radio and television and women could sing without a veil. Buz bazi used to be a form of solo entertainment in northern Afghan teahouses, in which a dambura player moved a marionette in the shape of a goat.

Bat

Dohol ( Dhol ) and Nagara (a pair of kettle drums ) were not only traditional musical instruments, but also served as a means of communication and announcement - a kind of "non-electrified telephone": with the help of kettledrum and light movements one made oneself understood (see also Herold ) .

Dhols in different shapes, colors and figures, small and large, single-skin or double-skin, are the typical festival instruments of the southern regions of the country. Up to six of these instruments are played vividly in the Atan dance of the Pashtuns.

Today the celebrations are held in specially built halls in the cities. The professional music groups of Charabat or professional amateurs are hired for these celebrations . Harmonium , tabla , guitar , sitar , drums and many European musical instruments are part of the music repertoire of the city music groups.

Under the direction of Abdul Ghafur Breshna , a radio orchestra was formed in the 1950s , which consisted of typical domestic and European musical instruments. His merit was the professionalization of Afghan folk music and hit. Thanks to his art of painting, some famous bazaars and buildings in the old town of Kabul could also be "captured".

Fanfare group This group is believed to be the oldest group in Afghanistan, formed during Amanullah Khan's reform period. The fanfare and percussion players perform at state acts, festivities, but also at weddings in the old town of Kabul.

Music groups

From the 1950s onwards, young people in the renowned schools, for example in the English-speaking Habiba High School, as well as in the German-speaking Amani secondary school and in the French-speaking Esteqlal Lycée, familiarized themselves with European musical instruments. On the school grounds of the Amani-Oberrealschule , founded by Germany in 1924 , the Republic of Austria opened a music school where German and Austrian music teachers (400 Germans in Kabul at the time) taught.

They performed at school concerts and formed the basis for the formation of music bands. Grand piano , piano , violin , guitar , trumpet , accordion , mandolin and numerous European musical instruments could be learned here. The groups presented this cultivated music at the events on the occasion of the independence festival. Each festival pavilion had its own music group.

Poems by the poets of the Pashto and especially the Persian language formed the lyrics of most of the singers. In the 60s and 70s Iranian singers like ( Googoosh ) sang some Persian songs composed in Afghanistan like Molla Mohammad Jan and Tscham e Sia Dâri . Persian singers like Ustad Zaland and Ustad Nainawaz made a great contribution to the development of the (Persian) musical culture in Afghanistan.

Awalmir and Gul Zaman were among the famous musicians of the Pashto language . The famous song by Awalmir was titled “Zema zeba Watan, da Afghanistan de” (My beautiful country - this is Afghanistan) and is still very popular with the Pashtuns today.

From unison to polyphony of the music

The attempts by composers to produce polyphonic music in Afghanistan in the 20th century date back to the 1950s. Well-known musicians from this early period include Farach Afandi, Abdul Ghafur Breshna , Ustad Zaland , Nainawaz and many others. You contributed to the establishment of a 30-member orchestra that was trained as part of the Radio Kabul training school. The award of foreign scholarships for the acquisition of sheet music played an important role in the development of polyphonic music in Afghanistan. The war impaired the project, but some of their musical skills and achievements were able to contribute to the reconstruction of the country, such as Babrak Wassa . The musicians who had to leave Afghanistan are confronted with polyphonic music mainly in Europe. Musicians like Amirjan Sabori , Tawab Arash , the couple Hafiz and Devyani, the young singer Sahar Afarin .

singers

Mermon Parwin and Asada are among the first women singers in Afghanistan whose singing was broadcast on the radio from 1951 . Asada's and Parwin's Nouruz song Samanak or Samano (pers. Seedling → dessert) has gone down in the history of the cultural area.

The singer Ustad Farida Mahwash , who had a hit in 1977 with "O Bacha" (pers. Hey, boy), is also famous . She was the first female singer in Afghanistan to be awarded the title Ustad .

In the Mawlana “Rumi Balkhi Memorial Service” organized by UNESCO on the occasion of his 800th year of birth, Mahwash sang the famous poem “Listen to the Nay ” by Rumi, with the following translation:

- Listen to what the nay (pipe) is saying

- she complains about their separation

- When parting in the swamp (Rohrfeld) I screamed (Nay),

- Wife and husband wept for me through my nay sound.

After the compulsory veil was abolished in 1959, Radio Afghanistan broadcast the songs of numerous women. Women also performed their art on stage. Other popular singers include Rochshana or Roxane, Hangama, Qamar Gul, Fatana and others whose music and singing were broadcast on television.

Popular music

Kabul is traditionally the regional cultural center of Afghanistan, with Herat , the pearl of Persia or Khorasan, to which Kabul also undoubtedly belongs, but is regarded as the home of traditional poetry and music texts. The language of the songs in Kabul is mainly Persian . In 1925 the Afghan Radio was founded, which was destroyed again in 1929. After its restoration in 1940, popular music spread throughout the country and quickly gained in importance.

Modern folk music did not gain ground until the 1950s with the spread of radio in the country, using orchestras with native, Indian and European musical instruments. The 1970s are widely considered to be the "Golden Age of Music" in Afghanistan: while popular music in Afghanistan had emerged in the 1950s, it had grown in popularity by the late 1970s. So-called amateur singers , who broke with the laws of traditional music, introduced new approaches to traditional folklore and all of the country's music. These amateur singers, who mostly came from the middle to upper classes of the population, include singers such as Sarban , Madadi , Ahmad Zahir , Ahmad Wali , Zahir Howaida , Rahim Mehryar , Mahwash , Haidar Salim , Salma Jahani , Hangama , Parasto , Farhad Darya , Farid Rastagar, his wife Wajiha Rastagar and other Persian (Tajik) singers, there were also some Pashtun singers who sang and still sing in both Pashto and Persian, such as Naghma and Mangal . Ahmad Zahir can be considered the most famous among them - his popularity far surpassed that of the others. In the 1960s and 1970s, Persian singers gained national and international recognition in Afghanistan, for example in countries like Iran and Tajikistan .

pop music

At the beginning of the 1970s, a four-piece music band appeared in Kabul for the first time, known in Kabul as the "four brothers band". Their music group consisted of three guitar players and a drummer. After that, many young people started such groups, which performed at the weddings of the more modern Kabulians. One of the groups is the Goroh-e-Baran ("Rain Band") founded by Farhad Darya .

Oppression and prohibition

Since the 1980s, music in Afghanistan has been increasingly suppressed and recordings for outsiders have fallen dramatically, despite the country's rich musical heritage. In the 1990s, instrumental music and public music-making in the cities in the Persian language were completely banned by the Taliban , while they themselves cultivated their own Pashtun culture, such as the national Pashtun dance Atan , and recorded songs by Awalmir and other famous Pashtuns in Pakistan that they brought to Afghanistan and sang. The followers of the Pashtun Sufi poet Rahman Baba sang Naa'd and Qawali on Fridays , played etc. a. Tabla and Rubab . Despite numerous arrests and the destruction of musical instruments in the big cities, Persian-speaking musicians were able to save some of their instruments.

Music in exile

Older generation

Exiled musicians and singers living in the USA and Europe kept up the different variations of the music from Afghanistan. This negative aspect, namely flight and immigration, not only allowed the musical diversity of Afghanistan to continue, but also all ethnic groups in the country, especially the Persian and Pashtu speakers, had the opportunity to continue their music.

New generation

The children of the older generation took it a step further and brought a new wind to the development of music. They recorded European musical instruments in their music and video clips and accordingly learned the instruments with notes, such as the fingerings of the guitar. Otherwise they tuned the guitar according to Eastern notation. They were also more open to other languages and cultures. Some sang songs that encouraged tolerance and togetherness. Pop singers from the 1990s onwards are Habib Qaderi , Wajiha Rastagar and her husband Farid Rastagar. Khaled Kayhan, Jawid Sharif, Nasrat Parsa , Qader Eshpari and Arash Howaida have also contributed to pop music .

Music rebirth in Afghanistan

Since the fall of the Taliban , both state and private television have endeavored to achieve a balance of broadcasts in terms of linguistic, ethnic, religious, denominational and musical diversity.

Many singers (popular musicians, folk musicians, amateurs and professionals) include music in the two official languages of the country in their repertoire. Some sing in three or four languages at once, with most singers singing in the Persian language.

Hip hop

Hip-hop is a popular style of music among young people in Afghanistan and in exile that is closely linked to traditional hip-hop music. Afghan hip-hop is sung in English , Pashto or Persian .

Musical instruments

- Tabla , Indian double timpani

- Harmonium , keyboard instrument probably introduced from India during the time of King Mir Scher Ali (1863–1866), a kind of easily portable organ

- Rubab , the oldest typical instrument in Afghanistan

- Zerbaghali , amphora-like drum made of fired clay, the larger opening of which is covered with fur.

- Dambura , a string instrument similar to the dombra , which is mainly found in the north

- Dayra , a frame drum

- Dhol or Doholak

- Tar

- Yaktar instrument with one string

- Dutar , two-stringed long-necked lute

- Setar "instrument with three strings", but has four, five or six

- Sarangi , Ghichak and Sarinda are string instruments

- Sarod

- Sitar

- Dilruba is a combination of sitar and rubab , a string instrument

- Tambour or tanbour

- Rebab

- Surnay

- Nay

- Daf

- Tschang , jaw harp. The Tschang harp existed until the 18th century .

- Santur (Sadtar), trapezoidal dulcimer

- Ghichak , strings in northern Afghanistan

- Tüidük , reed flute of the Turkmen in northern Afghanistan

- Tulak , regionally widespread recorder or transverse flute

- Waji , the Nuristani harp

See also

literature

- John Baily : Afghanistan. In: Music in the past and present . 2nd Edition. Sachteil, Volume 1, 1994, Col. 41-49.

- John Baily: Music of Afghanistan: Professional Musicians in the City of Herat . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1988, ISBN 0-521-25000-5 .

- Felix Hoerburger: Folk music in Afghanistan together with an excursus on Qor'an recitation and Torah cantillation in Kabul (= Regensburg contributions to musical folklore and ethnology. Volume 1). Gustav Bosse Verlag, Regensburg 1969.

- Hiromi Lorraine Sakata: Music in the Mind: The Concepts of Music and Musician in Afghanistan . Kent State University Press, Kent 1983, ISBN 0-87338-265-X .

- Mark Slobin: Music in the Culture of Northern Afghanistan . University of Arizona Press, Tucson 1976, ISBN 0-8165-0498-9 .

- Mark Slobin: Music in Contemporary Afghan Society. In: Louis Dupree, Linette Albert (Eds.): Afghanistan in the 1970s. Praeger, New York 1974, pp. 239-248.

Web links

- Information page about the music of Afghanistan

- Music in the Afghan North 1967-1972. Links to: Mark Slobin: Music in the Culture of Northern Afghanistan. 1976

- John Baily: "Can you stop the birds singing?" - The censorship of music in Afghanistan.

- John Baily: Afghan music before the war ( Memento from May 15, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Description of musical instruments

- John Baily: Ethnomusicological Research in Afghanistan: Past, Present, and Future. (PDF file; 105 kB) IIAS Newsletter, No. 27, March 2002

- Link to Saaz Music (English)

- ( Page no longer available , search in web archives: Zahir Howaida Tâjikzada - a portrait of a musician )

- Ostad Daud Khan

- asamai.com, Afghan-Hindu Association

- Thomas Burkhalter: Afghan music from Lake Geneva. Podcast about Khaled Arman and the Ensemble Kaboul . Norient, December 7th 2010

Individual evidence

- ↑ Hafiz and Devyani Ali

- ↑ Farsi Tajiki Dari Persian - Sahar Afarin in Kabul on YouTube , accessed June 23, 2019 (old song played for several voices and sung by Sahar Afarin)., Watan Watan Sahar Afareen on YouTube , accessed June 23, 2019., Sahar's CV Aferin ( Memento of February 27, 2009 in the Internet Archive ).