Azerbaijani language

| Azerbaijani | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Spoken in |

Azerbaijan , Iran , Iraq , Russia , Turkey , Georgia , Kazakhstan , Uzbekistan , Turkmenistan , Ukraine , Armenia | |

| speaker | 20-30 million | |

| Linguistic classification |

|

|

| Official status | ||

| Official language in |

|

|

| Recognized minority / regional language in |

|

|

| Language codes | ||

| ISO 639 -1 |

az |

|

| ISO 639 -2 |

aze |

|

| ISO 639-3 |

aze (macro language)

|

|

Azerbaijani language (proper name: Azərbaycan dili ) or Azerbaijan-Turkish ( Azərbaycan turkcəsi) , formerly also officially called Turkish (Türk dili) and therefore often unofficially referred to as such in everyday life, is the name for the official language of Azerbaijan , the closest relative of Turkic is one of the Oghuz , that is, one of the southwestern Turkic languages .

The national language of Azerbaijan is based on the Baku dialect and Azerbaijani (as a collective term for closely related languages and idioms ) is Iran's most important Turkic language with around 14 million speakers , which is based there on the city dialect of Tabriz .

Written languages

The written history of the Turkish languages began with the Orkhon runes . The runic alphabet was used until the Islamization period.

The literary language of Azerbaijan, which was written in the Perso-Arabic alphabet until 1929, is linked to Ottoman Turkish . The Ottoman texts are often identical to their Azerbaijani counterparts.

With the introduction of the New Turkic-Language Alphabet , presented in 1922 during a Muslim Congress in Baku , Azerbaijani was written in Latin letters from 1929 to 1938/39 . With the introduction of compulsory Russian lessons , Azerbaijani was written in a modified Cyrillic alphabet from 1939 at the latest .

With the beginning of the collapse of the Soviet Union (1988/89), the Azerbaijani SSR oriented itself more towards the west and thus towards Turkey . As the first Turkic state on the territory of the former USSR, it introduced a mandatory Latin writing system in 1991 .

Alternative names

Until about 1917, Azerbaijani was mistakenly referred to as " Tatar " by Russian officials . The Azerbaijanis themselves called their language Türki at that time , i.e. H. "Turkish", temporarily also "Azerbaijan-Turkish", "Azerbaijani" or otherwise (see chapter History, Alphabets and Name History ).

At the time of the Soviet Union (after 1937) the language was renamed “Азәрбајҹанҹа” (Azerbaijani) as a result of the Stalin policy and the republic had to switch to the new Cyrillic alphabet.

After 1989 the language was alternately referred to as "Türkcə" or "Türki" (Turkish) or as "Azərbaycan Türkcəsi" (Azerbaijan-Turkish or Azerbaijani Turkish). They were followed after 1990 by the names "Azərbaycanca" (Azerbaijani), "Turk dili" ( Turkish language ). In Iran , the Azerbaijani by officials as is Azerbaijani آذربایجانجا Azərbaycanca called.

The alternative abbreviation derived from Persian ( Azerbaijani آذرى Azeri , pronounced "Aseri") is also used alternatively in some western languages - especially in English. The term “Azeri-Turkish”, which had its counterpart in Azerbaijani Azəri Türkcəsi , is only used today by Turkish Turkology .

distribution

Azerbaijani is spoken today in Azerbaijan , Iran ( Iranian-Azerbaijan ), Turkey and numerous successor states to the former Soviet Union . In Turkey, all dialects of the old province of Kars can be counted as Azerbaijani. In the population census ( 1979 ) in what is now the Republic of Azerbaijan, 5.78 million people gave Azerbaijani as their mother tongue and around 27% of the minorities as a second language. This language was also spoken by around 860,000 people in the territory of the former USSR: 300,474 in Georgia , 282,713 in Russia (90% of them in Dagestan ), 84,590 in Armenia and 78,460 in Kazakhstan . The Turkmens of Iraq , estimated at 180,000 to 400,000 people, are for the most part to be seen as speakers of Azerbaijani.

Today Azerbaijani is generally divided into two main blocks: "North Azerbaijani" (Azerbaijani Quzey Azərbaycan Türkcəsi "North Azerbaijani Turkish" and Şimal Azərbaycan Türkcəsi "Northern Azerbaijan Turkish") is the state language of the Azerbaijan Republic. In addition, the “South Azerbaijan” (Azerbaijani Güney Azərbaycan Türkcəsi “South Azerbaijani Turkish” and Cənub Azərbaycan Türkcəsi “southern Azerbaijan Turkish”) are spoken as a minority language in Iran today .

North Azerbaijani was heavily influenced by Russian and South Azerbaijani by Persian .

The North Azerbaijani variant is the mother tongue of around 7.5 million people, and another 4 million are bilingual. It is divided into numerous dialects that also radiate far south and west: Quba, Derbent, Baku, Şemaxa, Salianı, Lənkərən, Qazax, Airym, Borcala, Terekeme , Qızılbaş, Nuqa, Zaqatalı (Mugalı), Kutkas, Erevan, Naxçevan, Ordubad, Qirovabad, Şuşa (Qarabaq) and Qarapapax .

South Azerbaijani is spoken by 14 to 25 million people, or approximately 20 to 24% of the Iranian population. This number also includes around 290,000 Afshar , 5000 Aynallu , 7500 Bahārlu , 1000 Moqaddam, 3500 Nafar , 1000 Pişagçi, 3000 Qajar, 2000 Qaragozlu and 65,000 Şahsavani (1978). Of these, around 9.8 million are recognized by the Iranian government as an “Azerbaijani minority”. South Azerbaijani is also divided into numerous dialects: Aynallu (Inallu, Inanlu), Qarapapak, Təbriz, Afşari (Afşar, Afshar), Şahsavani (Şahseven), Moqaddam, Bahārlu ( Khamseh ), Nafar, Qaragozlu, Piatagajçar. However, the linguistic affiliation of the so-called " Khorasan Turks " in northeastern Iran is disputed . From a linguistic point of view, this language stands between modern Turkmen and Uzbek and can probably be viewed as a transition dialect between the two Turkic languages .

Around 5000 South Azerbaijani speakers live in Afghanistan today . The ethnic group of the Iraqi Turkmen, who are called "Iraq Turks" after their home state and who are estimated to have between 900,000 ( UNO data ) and 2.5 million ( self-reported ), and the 30,000 Turks in Syria (1961) generally as a spokesman for South Azerbaijani. The discrepancy between the information given in Iraq is due to the fact that in Ottoman Iraq the Turkish language was the colloquial language in large parts of the country, especially within the Kurdish nobility and the urban population, so that one has to differentiate between the actual number of Turkmens and Turkish-speaking people; Especially in cities such as Kirkuk, Mosul or Arbil, Turkish was the colloquial language and was only slowly displaced by Arabic and later by Kurdish when the state of Iraq was founded, so that the actual number of Turkish-speaking people exceeds the two million mark, while the number of Turkmens is lower.

The languages of the Teimurtaş , also known as "Teimuri", "Timuri" or "Taimouri", in Māzandarān are also considered independent Azerbaijan-Turkish dialects . These come from Uzbek-Turkmen roots, and the approximately 7,000 speakers can be traced back to the Mongol ruler Timur . The Salçug ethnic group ( Kerman province ) are considered to be descendants of the Seljuks , while the origin of the Qaşqai has not yet been fully clarified. However, it is certain that their ancestors were predominantly of Oghus origin.

In 2010, the number of native Azerbaijani speakers is estimated at 23 to 30 million. According to the CIA Handbook, about 16.33 million live in Iran . This should be the most credible information. Other sources give higher or lower numbers depending on your political perspective. Ethnologue and some linguists such as B. Ernst Kausen also assume that there are around 23 million native speakers in Iran, with 40 million speakers worldwide if you add the number of secondary speakers.

Several hundred South Azerbaijanis live in Jordan and are counted among the "Turks" there. However, they call themselves "Turkmen".

| source | Number of native speakers | Share of total population | Total population of Iran |

|---|---|---|---|

| CIA World Factbook (2005) | 16.3 million | 24% | 68.017.860 |

| Ethnologue (2005) | 23 million | 34% | 67 million |

| Encyclopaedia of the Orient (2004) | 12 million | 18% | 67 million |

| Iranian embassy | 13.8 million | 20% | 69 million |

| MS Encarta 2006 | 17 million (all Turkic tribes combined) | all Turkic tribes together 25% | 68 million |

The Azerbaijani language has also been adopted as a cultural language by representatives of some national minorities such as Lesgier and Talish. Azerbaijani became the basis for the language development of the related Central Asian Turkic languages. Azerbaijani grammar became the basis of Uzbek, and especially Turkmen. Kazakh and Kyrgyz languages were also heavily influenced by Azerbaijani in the 1930s .

The language abbreviation according to ISO 639 is az(in the two-letter ISO 639-1) and aze(in the three-letter ISO 639-2).

Classification options

Azerbaijani is sometimes classified differently. The "Fischer Lexikon Sprachen" (1961) lists Azerbaijani as follows:

- Turkic languages

- Western branch

- Bolgarian group

- The oghous group

- Oghuz-Turkmen

- Oghuz-Bolgarian

- Oghuz Seljuk

- Azerbaijani

- Western branch

In contrast, the "Metzler Lexicon Language" (1993) divides Azerbaijani as follows:

- Turkic languages

- Southwest Turkish (Oghusian)

- Azerbaijani

- Southwest Turkish (Oghusian)

The current classification is given in the article Turkic languages .

History, alphabets and name history

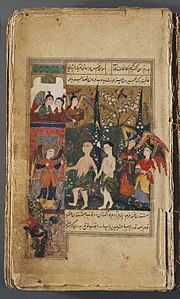

The Turkish-speaking tribal association of the Oghuz , from whose linguistic form the closely related Oghuz (south-west Turkish) languages such as Turkish , Turkmen and Azerbaijani developed, existed since the 7th century AD. The written Azerbaijani language arose together with the then almost identical Ottoman from the 11th century in the time of the Seljuks . Already in the late Middle Ages they used important poets, Nasīmī in the north and Fuzūlī (Füzūlī) in the south, who established Azerbaijani literature alongside older Persian and Arabic-speaking literature . It was written in the Persian-Arabic alphabet , which was used in northern Azerbaijan until the 1920s and in the southern part of Iran until today. Other classics of this literary language were Molla Pənah Vaqif or the first Shah of Persia from the Safavid dynasty , Ismail I , who elevated the Twelve Shia to the state religion in Persia, then with all of Azerbaijan, and his empire from the rival Sunni Ottoman Empire religiously separated. In the time of the Safavids and the early Qajars , Persian continued to be the language of administration and Arabic the language of religion, but Azerbaijani Turkish was the dominant language of the court in Tabriz , making it a respected written language and regional language of the upper class in the north-west of the empire older languages such as Old Azerbaijani (Āḏarī) , Udish or Tatisch gradually pushed back into everyday life.

From 1813, as a result of the Russian-Persian border wars in the Caucasus , Persia had to force several khanates from the historical regions of Arrān (between Kura and Aras ), Shirvan (north of the Kura) and northeastern parts of Azerbaijan (south of the lower Kura and Aras), which had been ruled by Persia up to that point. cede to the Russian Empire. After Ottoman territories in the region also fell to Russia, there were massive resettlements of Armenians (from the Ottoman Empire and from Arran) to the Russian-occupied areas of the former Persian province of Armenia . Thus, the Azerbaijani-speaking Turks southeast of the Caucasus were divided between two states - Russia and Persia . The northern areas, the former (annexed by Russia) regions of Arran, Shirvan and the northeast corner of historical Azerbaijan now form the state of Azerbaijan . The southern areas of Azerbaijan are now divided into three Iranian provinces, which together form the Iranian region of Azerbaijan .

The designation of the language by its speakers was very inconsistent in the late Middle Ages and early modern times . The old name "Turkish" ( Türk (i) ) or "Turkish language" ( Türk dili ) had become the exclusive name for the nomad associations and their language during this time and was avoided for the sedentary population and the upper class because it was a social one received a pejorative aftertaste. In the neighboring Ottoman Empire, the term " Ottoman language " was therefore generally used as a generic term. Because this name was unthinkable in the north-west of the then warring empire of Persia and the term “ Persian language ” denoted another language, only names derived from the regions, areas or cities in which it was spoken frequently remained, such as “ Shirvani ” ( şirvanli ), “ Gandschaisch ” ( gəncəli ) etc. In addition, supra-regional terms such as “national language” ( vətən dili ), “mother tongue” ( ana dili ) or “our language” ( dilimiz (ja) ) are often passed down in the sources. It was not until the linguistic and cultural reform movements in the Ottoman Empire and the Caucasus that began in the 1830s that the term “Turkish (language)” ( Türk (i) , Türkce , Türk dili ) was re-established as a socially overarching term for language.

In the north of Russia in the 19th century, from around Mirzə Fətəli Axundov , movements arose to reform the medieval literary language and bring it closer to the contemporary vernacular (also in Arabic script), which had already developed stronger dialectal differences to the Turkish vernacular of Anatolia . Axundov was also the first to propose a Latin alphabet for the Turkic languages, but it has not yet caught on. These renewed language variants (initially texts in the Anatolian-Turkish and Caucasian-Turkish / Azerbaijani vernacular were created side by side) were anchored in the modernization and enlightenment movement of Jadidism with a wide network of new schools, newspapers and publications. This also resulted in the separation of the northern dialects of Azerbaijani-Turkish - from which "New Azerbaijani" emerged in the following years - while the southern language area remained on the sound level of the old Azerbaijan-Turkish. Politically, at the end of the 19th century, Jadidism resulted in Pan-Turkist efforts to defend all Turkic peoples in Russia, the Ottoman Empire, Persia and the like. a. To unite countries as possible.

From the 1890s onwards, increasingly from the Russian Revolution of 1905–07 since Həsən bəy Zərdabi and Məhəmməd ağa Şahtaxtinski, efforts to unite the particularly similar dialects-speaking inhabitants of north-western Iranian Azerbaijan and the more northern Russian regions and use the name "Azerbaijan" joined Pan-Turkist goals. also to be transferred to the north, which until then was never called that ("Azerbaijanism", "Greater Azerbaijanism", "Pan-Azerbaijanism"). This program was also taken over by the Müsavat Partiyası , which after the breakup of Russia as the ruling party of the newly proclaimed Azerbaijani Democratic Republic (1918-20) officially transferred the name to the north, which was later retained by the Soviet Azerbaijani Soviet Socialist Republic and what is now the independent Republic of Azerbaijan . The Pan-Azerbaijani program never came into open opposition to Pan-Turkist goals; in the last year of the war, 1918, the government of the Democratic Republic of Azerbaijan was politically and militarily allied with the Young Turkish government of the Ottoman Empire.

The complex linguistic and cultural modernization, emancipation and political development corresponded to a contradicting development of the self-designation for the language of Azerbaijan. The earliest designation of the language as Azerbaycan dili (Azerbaijani language) and as Türki-Azerbaycan dili (Turkish-Azerbaijani language) for the dialects in the north are handed down by the same author in 1888 and in the following years both names became parallel, but increasingly next to the the self-designation Türk (i) dili (Turkish language) used in literature in the 1830s . While from 1905/07 texts of the Azerbaijani variant of the popular language completely replaced the Anatolian variant and the program of Pan-Azerbaijaniism became politically popular, paradoxically the designation of the language as "Turkish-Azerbaijani" or "Azerbaijani" was completely replaced by the designation as "Turkish" ( Türk dili , Türki , Türkçe ). Probably the cause was the Young Turkish Revolution in 1908 in the neighboring Ottoman Empire, which gave Turkish identities a boost. This designation remained common even during the reign of the first president of the Azerbaijani SSR (within the Soviet Union) Nəriman Nərimanov 1920-25. It was not until 1929, at a Soviet Turkologist Congress in Baku, that discussions were held as to whether the old designation "Azerbaijani language" or "Turkish-Azerbaijani language" should be reintroduced as the official designation, without the congress reaching a conclusion. It was not until 1938 that the designation of the language as Azerbaycanca (Azerbaijani) or Azerbaycan dili (Azerbaijani language) was officially and bindingly introduced.

In 1922, Azerbaijani reform forces developed a Latin alphabet, which they called the Uniform Turkic Language Alphabet or Yeni Yol ("new way"). They presented this alphabet to a conference of Turkologists in Baku in 1923 . This alphabet was so well developed that it was made mandatory for all non-Slavic languages of the USSR by 1930 . With the takeover, South Azerbaijani became independent to a certain extent, as it continued to be under Persian influence and retained the Perso-Arabic alphabet.

As part of the compulsory Russian lessons , Azerbaijani had to be written in a modified Cyrillic alphabet from 1940 .

After the collapse of the Soviet Union , a law passed in Azerbaijan on December 25, 1991 introduced the Turkey-Turkish alphabet, which was supplemented by five additional characters. As originally in neighboring Turkey , this alphabet is now called “ New Turkish Alphabet ”. At a meeting in Ankara (1990), the representatives of all Turkic countries decided to work out a Latin alphabet for the Central Asian countries and Azerbaijan within 15 years, which should be based closely on the modern Turkish alphabet.

On August 1, 2001, by a decree of President Heydər Əliyev, only the Latin alphabet was made binding for official correspondence and the Cyrillic alphabet - against the protests of Russia and the Russian minority in the country - was finally abolished.

In Dagestan , Russia , where around 130,000 Azerbaijanis live, the Azerbaijani language also has an official status as a recognized minority language, although it is still written there in the Cyrillic alphabet.

Pan-Turkish and panaserbaidschanisch nationalist Südaserbaidschaner use today next to the Arab and the modern Latin alphabets Turkey or Azerbaijan.

Azerbaijani alphabet

| Arabic | Latin | Latin | Cyrillic | Latin | IPA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| -1918 | 1922-1933 | 1933-1939 | 1958-1991 | 1992– | |

| ﺍ | A a | A a | А а | A a | [ɑ] |

| ﺏ | B b | B в | Б б | B b | [b] |

| ﺝ | C c | Ç ç | Ҹ ҹ | C c | [dʒ] |

| چ | Ç ç | C c | Ч ч | Ç ç | [tʃ] |

| ﺩ | D d | D d | Д д | D d | [d] |

| ﻩ | E e | E e | Е е | E e | [e] |

| ع | Ə ə | Ə ə | Ә ә | Ə ə | [æ] |

| ﻑ | F f | F f | Ф ф | F f | [f] |

| گ | Ƣ ƣ | G g | Ҝ ҝ | G g | [ɡʲ] |

| ﻍ | G g | Ƣ ƣ | Ғ ғ | Ğ ğ | [ɣ] |

| ﺡ, ﻩ | H h | H h | Һ һ | H h | [H] |

| ﺥ | X x | X x | Х х | X x | [x] |

| ی | I̡ ı̡ |

|

Ы ы | I ı | [ɯ] |

| ی | I i | I i | И и | İ i | [ɪ] |

| ژ | Ƶ ƶ | Ƶ ƶ | Ж ж | J j | [ʒ] |

| ک | Q q | K k | К к | K k | [k] |

| ﻕ | K k | Q q | Г г | Q q | [ɡ] |

| ﻝ | L l | L l | Л л | L l | [l] |

| ﻡ | M m | M m | М м | M m | [m] |

| ﻥ | N n | N n | Н н | N n | [n] |

| ڭ | N̡ n̡ | N̡ n̡ | [ŋ] | ||

| ﻭ | O o | O o | О о | O o | [ɔ] |

| ﻭ | Ɵ ɵ | Ɵ ɵ | Ө ө | Ö ö | [œ] |

| پ | P p | P p | П п | P p | [p] |

| ﺭ | R r | R r | Р р | R r | [r] |

| ﺙ, ﺱ, ﺹ | S s | S s | С с | S s | [s] |

| ﺵ | З з | Ş ş | Ш ш | Ş ş | [ʃ] |

| ﺕ, ﻁ | T t | T t | Т т | T t | [t] |

| ﻭ | Y y | U u | У у | U u | [u] |

| ﻭ | U u | Y y | Ү ү | Ü ü | [y] |

| ﻭ | V v | V v | В в | V v | [v] |

| ی | J j | J j | Ј ј | Y y | [j] |

| ﺫ, ﺯ, ﺽ, ﻅ | Z z | Z z | З з | Z z | [z] |

Font examples

(Article 1 of human rights )

Classic Azerbaijan Turkish in Arabic script

بوتون اینسانلار لياقت و حوقوقلارىنا گوره آزاد و برابر دوغولارلار. اونلارىن شعورلارى و وىجدانلارى وار و بیر بیرلرینه موناسىبتده قارداشلیق روحوندا داورامالیدیرلار

Uniform Turkic language alphabet (1929–33)

Butun insanlar ləjakət və hukykları̡na ƣɵrə azad və bərabər dogylyrlar. Onları̡n зuyrları̡ və vicdanları̡ var və bir-birlərinə munasibətdə kardaзlı̡k ryhynda davranmalı̡dı̡rlar.

Uniform Turkic alphabet ( Janalif ) (1933–39)

Bytyn insanlar ləjaqət və hyquqlarьna gɵrə azad və вəraвər doƣulurlar. Onlarьn şyurlarь və viçdanlarь var və вir-вirlərinə mynasiвətdə qardaşlьq Ruhunda davranmalьdьrlar.

First variant of a Cyrillic alphabet (1939–57)

Бүтүн йнсанлар ләяагәт вә һүгуларьна ҝөрә азад вә бәрабәр доғулурлар. Онлрьн шүурларь вә виҹданларь вар вә бир-бирләринә мүнасибәтдә гардашльг рунһунда давранмальд.

Final variant of the Cyrillic alphabet (until 1991)

Бүтүн йнсанлар ләјагәт вә һүгуларына ҝөрә азад вә бәрабәр доғулурлар. Онлрын шүурлары вә виҹданлары вар вә бир-бирләринә мүнасибәтдә гардашлыг рунһунда давранмалыдырланмалыдыр.

New Turkish alphabet (since 1991/92)

Bütün insanlar ləyaqət və hüquqlarına göre azad və bərabər doğulurlar. Onların şüurları və vicdanları var və bir-birlərinə münasibətdə qardaşlıq Ruhunda davranmalıdırlar.

Today's South Azerbaijani

Azerbaijani بوتون انسانلار حيثيت و حقلر باخميندان دنك (برابر) و اركين (آزاد) دوغولارلار. اوس (عقل) و اويات (وجدان) ييهﺳﻴﺪيرلر و بير بيرلرينه قارشى قارداشليق روحو ايله داورانماليدرلار.

- Transcription into Azerbaijani Latin Alphabet

Bütün insanlar heysiyyət və haqlar baxımından dənk (bərabər) və ərkin (azad) doğularlar. Us (əql) və uyat (vicdan) yiyəsidirlər və bir birlərinə qarşı qardaşlıq Ruhu ilə davranmalıdırlar.

Teaching

In the 1980s and 1990s, numerous publications and lexicons by the German Azerbaijan researchers Nemat Rahmati (Azerbaijani Chrestomatie , Azerbaijani-German Dictionary, Tapmacalar) and Yusif Xalilov (German-Azerbaijani Dictionary) were created.

In 2004 the German-Azerbaijani dictionary was created by Yazdani, a Berlin-based Turkologist. The Baku Germanist Amina Aliyeva published the first textbook of German for Azerbaijanis in the Azerbaijani language.

Today, Azerbaijani is taught at the German universities in Bochum, Hamburg, Berlin and Frankfurt am Main. The University of Vienna also offered the introduction to Azerbaijani (taught by Nasimi Aghayev) from 2001 to 2003.

See also

literature

- Lars Johanson, Éva Csató (Ed.): The Turkic languages. Routledge, London a. a. 1998, ISBN 0-415-08200-5 .

- Pocket dictionary Azerbaijani - German and German-Azerbaijani. Berlin 1944.

- Nemat Rahmati, Korkut Buğday: Azerbaijani textbook. Taking into account the North and South Azerbaijani. = Azerbaijani. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1998, ISBN 3-447-03840-3 .

- Nemat Rahmati: Azerbaijani - German dictionary. Verlag auf dem Ruffel, Engelschoff 1999, ISBN 3-933847-01-X .

- Ahmad Hüsseynov, Nemat Rahmati: Legal Dictionary German - Azerbaijani (= Almanca - Azerbaycanca hüquq terminleri lüğeti. ) Verlag auf dem Ruffel, Engelschoff 2002, ISBN 3-933847-06-0 .

- Angelika Landmann: Azerbaijani. Short grammar. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2013, ISBN 978-3-447-06873-4 .

Lexicons

- Helmut Glück (Ed.): Metzler Lexicon Language. Publishing house JB Metzler, Stuttgart u. a. 1993, ISBN 3-476-00937-8 .

- Heinz F. Wendt: Languages. Fischer library, Frankfurt am Main u. a. 1961 (= The Fischer Lexicon 25). Also: The Fischer Lexicon. Languages. Viewed and. corrected new edition. Fischer-Taschenbuch-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main October 1987, ISBN 3-596-24561-3 ( Fischer 4561).

Web links

- Azerbaijani alphabets and language examples

- North Azerbaijani

- South Azerbaijani

- German-Azerbaijani Language Book ( Memento from November 17, 2014 in the Internet Archive )

Individual evidence

- ^ Lars Johanson, Éva Csató: The Turkic languages. P. 82 ( books.google.de ).

- ↑ Altay Göyüşov: Türk dili, yoxsa azərbaycan dili? In: BBC. September 30, 2016, accessed May 22, 2020 (Azerbaijani).

- ^ A b Claus Schönig: Azerbaijanian. In: Lars Johanson, Éva Csató: The Turkic languages. P. 248.

- ↑ Azerbaijani language, alphabets and pronunciation. Retrieved January 16, 2018 .

- ^ Helmut Glück: Metzler Lexicon Language. P. 57.

- ↑ Helmut Glück: ibid

- ↑ azj: North Azerbaijani ethnologue.com

- ↑ azb: South Azerbaijani ethnologue.com.

- ↑ iranembassy.de ( Memento of July 24, 2006 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF)

- ^ Heinz F. Wendt: Fischer Lexicon Languages. P. 328.

- ^ Helmut Glück: Metzler Lexicon Language. P. 657.

- ^ Andreas Kappeler , Gerhard Simon , Georg Brunner (eds.): The Muslims in the Soviet Union and in Yugoslavia. Cologne 1989, pp. 21-23.

- ^ Andreas Kappeler , Gerhard Simon , Georg Brunner (eds.): The Muslims in the Soviet Union and in Yugoslavia. Cologne 1989, pp. 117-130.

- ↑ Audrey L. Altstadt: The Politics of Culture in Soviet Azerbaijan. London / New York 2016, p. 15.

- ↑ Audrey L. Altstadt: The Politics of Culture in Soviet Azerbaijan. London / New York 2016, pp. 13–16.

- ↑ В. А. Шнирельман: Войны памяти: мифы, идентичность и политика в Закавказье. (Viktor A. Shnirelman: War Monuments: Myths, Identities and Politics in Transcaucasia. ) Moscow 2003, pp. 34–35.

- ↑ Excluded from the alphabet in 1938