Indian classical music

The classical Indian music was throughout Indian history maintained in the upper classes, especially at princely courts. Since the 20th century it has been heard and practiced by the newly emerging educated middle class, comparable to Western classical music in Europe and America. The theory of this music has been extensively pursued in India since the time of the classical Hindu scriptures.

Possibly in connection with the traditional cultural north-south distinction of the Indian subcontinent and its population (speakers of Indo-Aryan languages in the north, speakers of Dravidian languages in the south), but at the latest since the influence of Islam in the northern and central areas of India since the Indian Middle Ages Music has also developed in two directions, Hindustan music in the north of India, as well as Pakistan and Bangladesh, and Carnatic music in the south (in the states of Andhra Pradesh , Karnataka , Kerala and Tamil Nadu ). These differ in terms of terminology, the musical instruments used and the preferences for different playing styles. From a western point of view, however, one can say that the two directions have much more in common than differences. Carnatic music is attributed a greater predilection for rich ornamentation, for vocal music and a somewhat lower proportion of improvisation .

Indian classical music is basically unanimous and is played in very small ensembles. There is no harmony and no changing chords ; the music unfolds on the basis of static tone scales, which are present in connection with rules for the ornamentation and the melodic progressions in the form of numerous ragas .

Indian classical music gained greater prominence in the West since the 1950s, and since then there have been numerous encounters between Western musicians of various genres and Indian musicians. The best known in the West are the sitar player Ravi Shankar , the sarod player Ali Akbar Khan , the tabla player Zakir Hussain , all Hindustan musicians, as well as the carnatic violinist L. Subramaniam and the vina player S. Balachander .

Sound system

| Svara | Shruti | west | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sat | S1 | Shadya | c |

| Ni | N4 | Tivra Ni | h + |

| N3 | Shuddha Ni | H | |

| N2 | Komal Ni | b | |

| N1 | Atikomal Ni | b- | |

| Dha | Qh4 | Shuddha Dha | a |

| Qh3 | Trishruti Dha | a- | |

| Qh2 | Komal Dha | as | |

| Qh1 | Atikomal Dha | as- | |

| Pa | P1 | Panchama | G |

| Svara | Shruti | west | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ma | M4 | Tivratara Ma | f sharp + |

| M3 | Tivra Ma | f sharp | |

| M2 | Ekashruti Ma | f + | |

| M1 | Shuddha Ma | f | |

| Ga | G4 | Tivra Ga | e + |

| G3 | Shuddha Ga | e | |

| G2 | Komal Ga | it | |

| G1 | Atikomal Ga | it- | |

| Ri | R4 | Shuddha Ri | d |

| R3 | Madhya Ri | d- | |

| R2 | Komal Ri | of | |

| R1 | Atikomal Ri | of- | |

| Sat | S1 | Shadya | c |

There is no concert pitch in Indian music . All scale indications are relative to a keynote that the musicians agree on for each performance. During the entire performance of a piece (usually in two octave registers and together with the fifth), this keynote is played as a drone on the tanpura or the shrutibox , and occasionally also on the jew's harp ( morsing ).

The octave is divided into 22 micro-intervals of different sizes , called Shruti ('that which one hears'). The exact derivation of this classification from vibration conditions and also its exact location has been the subject of theoretical speculation and practical variation for two millennia.

From this stock seven- step scales ( sargam ) are formed; the tones are called Svaras ('that which has meaning') and are denoted by the tone syllables sa ri ga ma pa da ni (“Sargam” is an acronym from these tone syllables). The exact meaning of a note such as "sa" or "pa" depends on the chosen keynote and the chosen scale. The tone syllables are abbreviations of the names Shadya (father of the six others), Rishaba (bull), Gandhara (perfumed), Madhyama (middle), Panchama (fifth), Dhaivata (subtle, balanced), Nishada (sitting). The table shows the corresponding Shruti versions for the Svaras and their western counterparts in C major (where + and - denote an increase or decrease of about a quarter tone). The Shruti indications follow the Hindustan system. “Shuddha” denotes the standard tone, “Tivra” the increase by a semitone, “Tivratara” by a semitone + a Shruti; "Komal" is the lowering of a semitone, "Atikomal" the lowering of a semitone and an additional shruti.

Metric

The metric of Indian classical music is mainly carried by drums struck with the fingers ( tabla in the north, mridangam in the south) and is organized in rhythmic cycles called tala (also Taal or Tal , in the south Talam ). These are comparable to the Western bars , but the units are significantly longer (in individual cases up to 100 beats, usually around 10 to 20). Internally, they are again divided into subsections. In North Indian music, the basis of a tala is a precisely specified sequence of different drum beats, which can be expanded in the course of the performance, which are denoted by symbols ( Bol ). These syllables are also recited by the tabla players for memorization. In South Indian music, the predominant system is based on sequences of beat numbers, which are usually represented by singers (and audience) during the performance using canonized hand gestures.

In both North India and South India, however, by far the most common tala for western ears sounds like a simple four-quarter time: The most common north Indian tala is the Tintal with 16 beats, as a bol sequence dha dhin dhin dha | dha dhin dhin dha | dha tin tin ta | ta dhin dhin dha . The most common South Indian Talam is called Adi (4 + 2 + 2).

ornamentation

The notes of Indian music are often provided with ornaments ( gamaka ). Typically every single note, even in faster sequences, is decorated. There are grace notes , slow vibrato , slow glissandi (in string instruments with frets such as vina or sitar realized by changing the pressure on the fret) and other variants.

Melody

The central concept of Indian melody is the raga (also called raag or rag , in southern India ragam ). A composition or improvisation always belongs to one of several hundred ragas named by name, a framework that captures the melodic characteristics. A raga consists of an ascending and a descending scale of five to seven tones. The ascending and descending scale can differ both in the tones themselves and in the number (compare the western melodic minor , in which the tones of the ascending and descending scale differ). In this scale system, a main tone ( vadi ), which can deviate from the fundamental Sa played in the drone , a secondary tone ( samvadi ) and other tone rolls are marked, the tones are hierarchically arranged in their functions, the frequency and type of their use are regulated (e.g. B. only as a passing note , preferably with a certain type of ornament, etc.). Ragas are associated with a specific emotion to be expressed and a preferred time of day for the performance.

The Raga Bhupala, for example, is described as follows: The scale has five notes and consists of the same tones, ascending and descending: S R1 G1 P Dh1 (c, des-, es-, g, as-). Dha is Vadi, Ga is samvadi. Ascending lines begin on the deep Dha. Melodic phrases often end in Sa and Pa. A characteristic melodic phrase is `Ri ´Ga Ri ~ Sa (` and ´ denote Kan s, short suggestions from above or below. ~ Is an andolan , a long, slow vibrato). Ri and Dha are often played with light vibrato. It is a cheerful morning raga.

Basically, a piece is always based on a single raga. An exception are the so-called ragamalikas (literally raga garlands), in which several ragas peel off like potpourri .

Instruments

Classical Indian music is usually performed by a small ensemble in which the musicians take on three roles (melodic leadership, percussion, drone), each with one or two players.

The melodic guidance is taken over by a singing voice or a melody instrument (especially in South Indian music you often have two singing voices, two melody instruments, or a singing voice and a melody instrument). Traditionally, the idea prevails that Indian music is “actually” vocal music and that the melody instruments should emulate the characteristics of the singing as much as possible. The singing is not always text-bound; often long composed or improvised passages are Svara chants - the tone syllables (Sa, Ri, Ga, Ma etc.) are sung.

The most important melody instruments in Hindustan music are the plucked sitar , the sarod , the rudra vina , the string instrument sarangi , the flute bansuri, and the double reed instrument shehnai (actually a folk musical instrument introduced into classical music by Bismillah Khan during the 20th century .) In Carnatic music, the violin (which perhaps came to Indian music from Europe in around 1800) , the Sarasvati vina , the short flute venu and the long double reed instrument nadaswaram dominate .

It is important for all these instruments to be able to infinitely influence the pitch: For example, by using the fretless strings on the violin and sarod , or the frets on the sitar and vina , which are far removed from the fingerboard , which can infinitely encompass intervals of up to a fifth through finger pressure variations , or the finger holes of the wind instruments, which allow continuous transitions by partially covering them.

In addition to the violin, other European instruments of classical Indian music were developed, such as the electric guitar , electric mandolin or the saxophone .

The most common percussion instrument in Hindustan music is the tabla kettle drum pair . In Carnatic music one usually finds the double occupation consisting of the double-cone drum mridangam and the clay pot ghatam, which is beaten with the hands .

The drone on which the music is based is usually supplied by the tanpura ; Today (also in concerts) it is often replaced by the shrutibox or the harmonium .

The harmonium is also used in classical Indian music as a melody instrument; However, since it cannot reproduce the Indian micro-red tones, but is tied to a tempered scale, the harmonium is not viewed by many as a serious instrument. There were early attempts to introduce Shruti-capable harmonium variants, but these never caught on.

Teamwork

In the classic three-part ensemble (of which a “voice” as drone provides the basis, but does not take part in the musical events) there is a lively rhythmic interplay between percussion instrument and melody instrument / singer. A string instrument is often added to the singer / main soloist ( usually a sarangi in Khyal in northern India, the violin in southern India), which plays the composed passages in unison with the soloist, and in improvised parts tries to imitate the soloist's melodies as he plays.

Since the middle of the 20th century, the jugalbandi (literally "twins") has become more and more popular, in which two (mostly well-known) soloists appear on an equal footing. Jugalbandis of Carnatic and Hindustan musicians are popular.

Genera and forms

Raga / Ragam, Tanam, Pallavi

The presentation of the musical characteristics of a raga in a multi-part, extended form determined primarily by improvisation, which can take over an hour, has become the epitome of classical Indian music, especially in the West, and, according to Hans Oesch, represents “the pinnacle of musical Contemporary Indian art ”. In northern India this genre is named simply after its most important object, the raga , in the south after the usually three-movement structure as Ragam Tanam Pallavi .

Alap

The first part is a gradual exposition of the melodic material and is called Alap in the north and Alapana in the south . It can occasionally be very short and consist only of playing the ascending and descending scales of the raga with the associated decorations. Usually, however, it is very extensive and can last an hour. In addition to the drone, only the melody instrument or the singer plays. The tones of the raga are introduced individually in rhythmically free improvisation in their ornamentation characteristics and typical melodic embedding determined by the raga, so that the listeners (and also the musicians) are attuned to the tone system that is thus formed. Vocal music usually does not sing text, but rather meaningless syllables. The notes appear first in the middle octave, then the low and high octaves are added.

Jod and Jala, Tanam

The second part follows without a break. In the south it is called Tanam , in the north Jor and Jhala or Jod and Jhala and is also often viewed as part of the Alap. This middle section is characterized by the fact that the soloist develops a rhythmic pulse that is not yet organized in talas. In the north, called iodine or Jor (जोड़) the structure of this pulse, which then in Jhala is played at a fast pace and rhythmic complexity. Here, too, the percussion instrument is usually still silent; Players of stringed instruments such as the sitar or sarod strike the sympathetic strings of their instrument to underline the meter. In the south, the Tanam has become the most important and often the longest part of the shape. Unlike in the north, the Tanam remains in the medium speed range and focuses on the development of rhythmic figures that are named after animals (frog, horse, elephant, etc.). Occasionally the mridangam drum also plays a part in the elaboration of these figures, but without tala structures.

Bandish or Gat, Pallavi

Only in the third part do melodic themes, the percussion instrument and the tala metric come into play. The South Indian name Pallavi (which usually denotes the chorus line of a song) already suggests that this theme is just a short melodic phrase, a tala cycle long. The North Indian term Gat is used for instrumental, Bandish for sung versions. The theme is initially played in a rondo-like alternation with improvised parts. This is followed by longer improvised parts, with solo parts of melody instrument / singer and drum and improvisational interplay between the two; the pace is increased several times during the course (North Indian names for the emerging parts are Vilambit , Madhya Laya and Drut ). The improvisers are not bound by the melodic and rhythmic phrases of the topic, but only by the framework of the raga and the tala.

Kriti

The Kriti (other transcription: kṛti or Krithi ) is the most important musical art form in the South. It is an extended song composition that is performed with composed variations and improvised parts.

A Kriti is usually performed by a singer (or a female singer) and a violin, as well as the rhythm section (usually mridangam and ghatam) and drone. Two singers or a melody instrument can take the place of one singer.

A Kriti performance begins with an optional alapana . Then the one or two refrain lines of the text are sung repeatedly in the Pallavi ; the melody is embellished more and more. This is followed by the Anupallavi , the next one or two lines of text, which melodically form a slight contrast to the Pallavi. These lines, too, are presented simply at first, then decorated. This is followed by an optional cittasvaram , a kind of cadenza , a few tala cycles long , sung in Indian tone syllables and using the melodic material of Pallavi and Anupallavi. Another Pallavi follows, with the refrain lines being sung in an embellished form. The Charanam contains the last lines of text, which are melodized based on the material by Pallavi and Anupallavi. They are performed with composed and improvised variations, followed by a faster cittasvaram. The conclusion is a repetition of Pallavi or Anupallavi.

Varnam

A varnam usually opens a concert of carnatic music. It is similar in size and structure to a Kriti. However, there are almost no improvised parts. In the form of the rhythmic Pada Varnam , it is used to accompany classical Indian dance. A Varnam usually begins at a slow pace, which later allows for virtuoso increases.

Gitam

The Gitam (song) is the starting point of the more developed carnatic genres: A simple song form, which, however, already has the classic structure in Pallavi, Anupallavi, Charanam. Gitams are also sung virtuously and richly in ornamentation, as is usual in carnatic chant.

Dhrupad

The dhrupad is a time-honored genre of Indian classical music that is now part of Hindustan music. The dhrupad is usually sung, usually with a male voice; the drum used is not the tabla, but the pakhawaj , which is similar to the south Indian mridangam . The singing begins with wide glissandi and increases to fast, dynamic ornaments in a strictly defined form. Improvisation only occurs in a very limited form. The formal structure is similar to the South Indian song forms, only the names are different: an alap as opening, sung with meaningless syllables; then the sthayi (also asthayi ), the first line of the song in the lower half of the three octave range; it follows the Antara , the second line of the song, now in the upper half of the tone range, and finally the Samcari, the last two lines of the song, the melodic material of which is based on Sthayi and Antara and is now developed in variations over all three octaves. The conclusion is formed by the Abhoga, a repetition of the Sthayi in a rhythmically accelerated form. Melody instruments suitable for the dhrupad are above all the rudra vina and the now very rare sursingar .

Similar styles to the dhrupad are dhamar and tappa , which are performed more emotionally and with more freedom.

Khyal

The khyal (also khayal ) forms a kind of counterpoint to the dhrupad in Hindustan music. The aim here is to showcase the virtuosity and improvisational skills of the singer. The singing is rich in ornamentation of all kinds and consists for the most part of textless syllables. The singer is faced with a second melody instrument (usually a sarangi or harmonium) that tries to imitate his phrases or enters into a dialogue with him. A khyal begins with an optional short alap; This is followed by Sthayi and Antara as in the Dhrupad and another Sthayi part, and then an extended improvisation part (also called Alap), in which the tabla also plays. Sthayi and Antara are repeated and alternate rondo-like with parts of variation ( Boltan and Tan ).

history

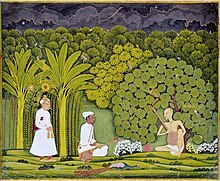

Music plays an important role in Indian mythology and epic. Sarasvati , the goddess of wisdom, is represented with a vina; the heroes of epic texts like the Ramayana are often trained musicians.

Since its creation in the centuries around 1000 BC u. Z. the texts of the Vedas and other religious texts are recited by the Brahmins in a stylized, speech melody and rhythm of the Vedic Sanskrit recited spoken song ( Samagan , 'melody song ') with only three pitches and two tone durations. The three tones are called Udatta ('raised'), Anudatta ('not raised') and Svarita ('sounded'). Finally, a system of seven notes ( Svaras ) was created.

The invention of the vina is ascribed to the oldest Indian music theorist Narada , whose life data are mythically transfigured today. In his work Naradya Shiksha ('Instruction') he examines the relationship between sacred and secular music. The name Narada has been adopted as a name of honor by four different authors, so that the assignment is further obscured.

The sage Bharata Muni is the Natyashastra attributed to the basic Indian work on aesthetics, dance and music. The time of origin lies between 200 before and 300 after our era. Based on the teaching of emotions ( Rasa ), elements of the ancient Indian music theory Gandharva are described in this work : The Shrutis, the Saptak, the Svaras. The word raga does not appear, however; Instead there is a system of Jatis , i.e. (tone) genders, which, like the later ragas, are also decisive for the formation of melodies. This work marks the beginning of a long tradition of classical Indian music theory.

After the end of the Gupta dynasty , the Jatis developed into the ragas system. The first work to elaborate this in detail is the Brihaddesi des Matanga , written in the 9th century . During this time, religious texts began to be written not exclusively in Sanskrit, but in the various national languages, which also led to a diversification of musical styles.

After the end of the Gupta period, the north of India was first ruled by the White Huns and later by various Muslim empires. This intensified the influence that has always had an impact on North Indian music from the north of non-Indian musical cultures and which became visible in the course of the next centuries and led to the development of northern and southern styles of playing.

The musicians Lokana Cavi and Jayadeva, who worked at the Bengali court in the 12th century, have not yet felt much of this. The Raga-Tarangini , published in 1160 , the only surviving book by Lokana Cavi, represents 98 ragas. Jayadeva, who has emerged primarily as a poet, gave the song and dance rhythms of the various sections as talas in his erotic poem Gita Govinda .

The Sangita Ratnakara of Sarangadeva (1210–1247) is the last music-theoretical text of India, to which both the Hindustan and the Carnatic tradition refer. Sarangadeva came from the far north, from Kashmir , but worked at a Hindu princely court in the Deccan in central India. At that time the north of India was under Islamic rule, which eventually extended to the Deccan. Sarangadeva had an insight into the music scene in both the north and south of India. In its meaning, the Sangita Ratnakara is equated with the Natyashastra. It is a comprehensive systematic presentation of all aspects of Indian music theory. In particular, it contains a detailed representation of 264 ragas and outlines a notation system.

Amir Chosrau (1253-1325) was the first known Islamic musician and music theorist in India. He was born in northern India and is of Turkish descent. He was court musician in Delhi . He studied Persian, Arabic and Indian music; His preference was Indian, which he enriched with Persian and Arabic elements. The invention of the sitar is attributed to him (probably wrongly) ; However, he introduced the movable frets (characteristic of the sitar) for a variant of the vina. Another legend ascribes the invention of the tabla double drum to him by cutting a pakhawaj , a double- skin drum that can be played horizontally, in the middle. Chosrau invented some new ragas and introduced the Islamic style of Qawwali and the syllable chant of Tarana from Persian roots .

Chosrau also marks the point in time when Indian classical music was split into Hindustan and Carnatic styles. It would be centuries before the musicians of the North and the South began again to take seriously other than hostile notice of one another.

In contrast, there was and is no dividing line between Muslim and Hindu musicians in northern India. Muslims and Hindus make music together, teach each other and even sing religious music of the other religion.

In the two centuries after Chosrau, new genres emerged in Hindustan music: the kirtan , a Hindu alternating chant that has its main focus primarily in eastern India; the strict vocal style of Dhrupad and in this gesture towards Asked Khayal , which offers the performers room for interpretation and technical brilliance.

In the early 16th century, the Mughals took power in northern India and expanded their rule further south. The most important Mughal Mughal was Akbar I , who is known for complete religious tolerance and promotion of the arts. This also affected the music. Tansen (1506–1589), who is considered the most important Indian musician at all, worked at Akbar's court . Tansen's father was a Hindu Brahmin but was raised by a Sufi fakir . He was a gifted singer (especially in the Dhrupad style); Legends tell of the magical effect that emanated from this song. Some of the most famous ragas come from him; he also made a name for himself in the sifting through and systematizing of the ragas and put together a list of about four hundred.

In South India, Carnatic music continued to develop unaffected by Islamic music, although large parts of South India were also ruled by Islam. This is justified with the particularly conservative structure of the South Indian Hindu culture and society. The hymn composers ( Alvars ) had a firm role in temple culture , and the most important of them was Purandara Dasa (1484–1564), a contemporary of tansen. His hymns are still sung frequently today, and his music also influenced Hindustan music.

The South Indian music theorist Venkatamakhi developed the melakartas ordering principle for the carnatic ragas in his work Chaturdandi-Prakashika in 1660 . There are 72 main ragas from which the others are derived. The Melakarta system is still used in Carnatic music to this day. Tansen had proposed a similar system a little earlier for the Hindustan ragas; other proposals followed, but none of these systems prevailed in North Indian music until the early 20th century.

The most famous composer of Carnatic music is Thyagaraja (1767–1847). He wrote a great number of Kritis , religious songs, many of them in Telugu . Three musical schools of Carnatic music can be traced back to his students. He and his two great contemporaries Muthuswami Dikhshitar and Syama Sastri are known as the Trimurti ( Trinity ) of Carnatic music.

While the South Indian musicians continued to attach importance to adhering to the standards of Venkatamakhi and to keep their music from changing, the schools and court music groups of North India increasingly distanced themselves from each other in style and also from classical tradition. At the beginning of the 19th century, the practice of musicians was far removed from the teachings of theorists. So it happened that the standard tone scale ( suddha ) was replaced by the original (in Western terms) Doric scale by an Ionic , i.e. a major scale . The Maharaja of Jaipur , Pratab Singh Dev , convened a conference to canonize this change in the reference scale and published the result in Sangita Sara around 1800. Further activities followed to capture North Indian music and theory to practice adapt. Important authors here are Khetra Mohan Goswami ( Sangita Sara 1863) and Krishnadhan Banerji (1846–1904). At the end of this series is the most important, Vishnu Narayan Bhatkhande (1860–1936). In years of study he went to various gharanas (traditional music schools) all over India , collected playing styles, techniques, melodies and convinced the musicians to make their first recordings for the new medium of the record . He tried to systematize and standardize North Indian music. His division of the Hindustan ragas into ten scale types thata based on the carnatic system of Venkatamakhi had a lasting effect. This systematisation has been criticized as being too simplistic and incorrect in places, but has since been in general use as a reference system.

In the 20th century, the role of classical Indian music changed from an elite institution, which was mainly operated at royal courts and temples, to part of the cultural identity of the rapidly emerging Indian middle class. The Indian state supported this development as much as possible, for example through the program of All India Radio and through courses at universities (the same applies in Pakistan and Bangladesh ). The music found its entrance into the concert hall, where it is usually presented with microphone amplification. The audience is made up of music connoisseurs, the Rasikas . Knowledge of the ragas, appreciation of playing techniques and making music are important educational features; superior daughters learn singing or instruments to be upgraded in the marriage market. The exclusivity with which a budding musician in earlier times, living in the house of the teacher who carefully selected him as a student, could and had to deal with music is no longer possible today due to lack of time.

Music samples

- ↑ a b Zakhir Hussain demonstrates the Bols in cooperation with the bluegrass banjo player Béla Fleck and the classic double bass player Edgar Meyer youtube.com

- ↑ Demonstration of the Shruti on the Sarod (English, 6 parts) youtube.com , youtube.com , youtube.com , youtube.com , youtube.com , youtube.com

- ↑ Demonstration of the Gamakas with singing and vina (English) youtube.com

- ↑ A four-year-old South Indian “child prodigy” demonstrates his talent in recognizing ragas. youtube.com

- ↑ lessons in advanced south Indian Svara singing youtube.com

- ↑ Asad Ali Khan plays Rudra vina youtube.com

- ^ Jugalbandi of a Hindustan and a Carnatic singer (6 parts) youtube.com , youtube.com , youtube.com , youtube.com , youtube.com , youtube.com

- ↑ Maha Ganapathim, a Kriti by Muthuswami Dikhshitar, sung by Nagavalli and Ranjani Nagaraj youtube.com

- ↑ Two interpretations of the Jalajaksha Varnam youtube.com , youtube.com

- ↑ Dhrupad, sung by Ritwik Sanyal (5 parts) youtube.com , youtube.com , youtube.com , youtube.com , youtube.com

- ↑ Vedic chant with three and five tones

- ↑ Venkatachala Nilayam by Purandara Dasa, sung by amateurs and professionals. youtube.com , youtube.com , youtube.com . Here is the text: celextel.org

- ↑ A Kriti by Thyagaraja, played on two Vinas: youtube.com

literature

- Alain Daniélou : Introduction to Indian Music . 5th edition. Noetzel, Wilhelmshaven 1996, ISBN 3-7959-0183-9 .

- HA Popley: The Music of India . Nabu Press, 2010, ISBN 978-1-176-35421-0 (English, first edition: Calcutta 1921, reprint).

- Survanalata Rao, Wim van de Meer, Jane Harvey: The Raga Guide . Ed .: Joep Bor. Nimbus Records, Rotterdam 1999 (English, book with 4 CDs).

- Emmie te Nijenhuis: Indian Music . In: J. Gonda (Ed.): Handbuch der Orientalistik, second section . tape VI . EJ Brill, Leiden / Cologne 1974, ISBN 90-04-03978-3 .

- Hans Oesch : Non-European Music 1 . In: Carl Dahlhaus (ed.): New manual for musicology . tape 6 . Laaber, Wiesbaden 1980, ISBN 3-7997-0748-4 .

- Reginald Massey and Jamila Massey: The Music of India . Abhinav Publications, New Delhi 1996, ISBN 81-7017-332-9 (English).

Individual evidence

- ↑ Danielou 1975, p. 40

- ↑ after Popley, p. 5

- ↑ Raga Guide, p. 42

- ↑ Danielou 1975, p. 64

- ^ NHM, p. 277

- ↑ Danielou 1975, p. 85

- ↑ Raga Guide, p. 6

- ↑ Te Nijenhuis, p. 112

- ^ NHM, p. 279

- ↑ Te Nijenhuis, p. 103 for the entire section

- ↑ te Nijenhuijs p. 93

- ↑ Massey and Massey, pp. 13 f

- ^ Massey and Massey, pp. 18 f

- ↑ Massey and Massey, p. 22 ff

- ^ Massey and Massey, p. 24 f

- ↑ a b Massey and Massey, p. 40 f

- ^ Massey and Massey, p. 40

- ^ Massey and Massey, pp. 46f

- ^ Massey and Massey, p. 57

- ^ Massey and Massey, p. 59

- ↑ Mobarak Hossain Khan: Article in the Banglapedia; Edited by Asiatic Society of Bangladesh

- ^ Massey and Massey, pp. 70ff