Dravidian languages

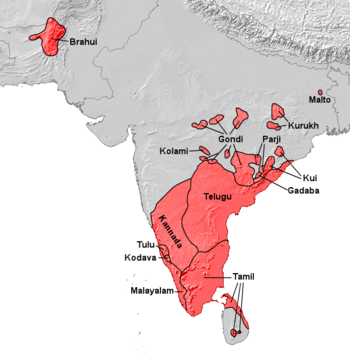

The Dravidian languages (also Dravidian ) form a language family widespread in South Asia . Its distribution area mainly includes the southern part of India including parts of Sri Lanka , as well as individual language islands in central India and Pakistan . The 27 Dravidian languages have a total of over 240 million speakers. This makes the Dravidian language family the sixth largest language family in the world. The four main Dravidian languages are Telugu , Tamil , Kannada and Malayalam .

The Dravidian languages are not genetically related to the Indo-Aryan languages spoken in northern South Asia , but they have strongly influenced them typologically . In return, most of today's Dravidian languages have adopted many individual words , especially from Sanskrit , the classical language of Hinduism .

Origin and history of language

The prehistory of the Dravidian languages is largely in the dark. Whether the Dravidian languages are the languages of the indigenous people of India or whether and how they came from outside to the subcontinent is not sufficiently clear. Some researchers assume that the speakers of the Dravidian languages were originally native to the mountains of western Iran , the Zāgros Mountains , and were around 3500 BC. Began to immigrate from there to India, until the Dravidian languages around 600–400 BC. B.C. to the southern tip of the subcontinent. This thesis is related to speculations about a possible relationship between the Dravidian languages and the Elamite or Uralic languages spoken in the south-west of Iran , but cannot be proven. An analysis of the common Dravidian hereditary vocabulary , on the other hand, offers indications for India as a possible original home of the Dravidian languages. In the reconstructed Dravidian proto-language there are words for various tropical plants and animals found on the subcontinent (coconut, tiger, elephant); For animal species such as lion, camel and rhinoceros or terms such as “snow” and “ice”, however, no Dravidian word equations can be established.

It can be considered certain that the Dravidian languages were spoken in India even before the Indo-Aryan languages spread (1500–1000 BC). Together with the Munda and Sino-Tibetan languages, they form one of the older language families native to India. Even in the Rigveda , the earliest writings of the Indo-Aryan immigrants, Dravidian loanwords can be traced, which is why there is reason to believe that the Dravidian languages once reached as far as northern India. The Dravidian language islands scattered today in northern India ( Kurukh , Malto ) and Pakistan ( Brahui ) could be remnants of the former language area. When trying to decipher the script of the Indus culture, many researchers assume that the bearers of this culture also spoke a Dravidian language, but this could only be finally decided after the Indus script has been deciphered .

The historically tangible era of the Dravidian languages begins with a Tamil inscription by the Emperor Ashoka from the year 254 BC. The first inscriptions in Kannada date from the middle of the 5th century AD, the oldest Telugu inscriptions from around 620, the first Malayalam inscriptions were written around 830. A literary tradition developed in all four languages one to two centuries after the first written evidence. The Tamil literature in particular, which probably goes back to the first centuries AD, is significant because it has a largely independent origin and is not based on Sanskrit literature like the literatures of the other Indian languages . Tamil, Kannada, Telugu and Malayalam were the only Dravidian languages to develop into literary languages . In addition, Tulu has been attested in inscriptions since the 15th century, and there has been a sparse literary tradition since the 18th century. The other Dravidian languages, which are largely non-scripted, have a rich oral literature , but records of this have only recently existed.

Geographical distribution

The Dravidian languages have their main distribution area in the south of India , while in the north of the subcontinent mainly Indo-Aryan languages are spoken. There are also scattered Dravidian language islands in central and northern India and in Pakistan .

The four largest Dravidian languages are among the total of 22 official languages of India and are each official language in one of the five southernmost states of the country: The largest Dravidian language, Telugu , is spoken in the states of Andhra Pradesh and Telangana and has around 81 million speakers. The Tamil is of 76 million people mainly in the Indian state of Tamil Nadu and parts of Sri Lanka spoke (5 million). In the state of Karnataka is Kannada common. The number of speakers is 44 million. Malayalam , the language of the state of Kerala , is spoken by 35 million people.

Also in the south Indian heartland of the Dravidian language area, around the city of Mangalore on the west coast of Karnataka, about 1.8 million people speak Tulu , which has a certain literary tradition. The Kodava , which is widespread in the interior of Karnataka, has around 110,000 speakers and has only been in written use for a few years. In the Nilgiri Mountains between Tamil Nadu, Karnataka and Kerala, some smaller illiterate languages used by the tribal population ( Adivasi ) are common, which are summarized as Niligiri languages: Badaga (130,000 speakers), Kota (2,000), Irula (200,000) and Toda (600).

In central and northern India as well as Bangladesh and Nepal, especially in inaccessible mountain and forest areas, there are a number of linguistic islands of illiterate Dravidian tribal languages. These include Gondi (3 million speakers in a widely dispersed area in Telangana, Madhya Pradesh , Chhattisgarh , Maharashtra and Orissa ), Kolami (130,000, Maharashtra and Telangana), Konda (60,000), Gadaba (both on the border between Andhra Pradesh and Orissa ), Naiki (Maharashtra) and Parji (50,000, Chhattisgarh). The closely related idioms Kui (940,000), Kuwi (160,000), Pengo and Manda , all of which are spoken in Orissa, are often grouped together as Kondh languages. Further north, Kurukh is spoken by 2 million speakers in Jharkhand , Bihar , West Bengal , Orissa, Assam , Tripura , Bangladesh and the Terai in Nepal. Malto (230,000 speakers) is also common in northern India and Bangladesh. Today the Brahui (2.2 million speakers) spoken in Balochistan in the Pakistani - Afghan border region is completely isolated from the rest of the Dravidian-speaking area . It is unclear whether this distant exclave represents a remnant of the original distribution area of the Dravidian languages before the spread of Indo-Aryan, or whether the Brahuis immigrated from central India later.

As a result of migration processes during the British colonial era, Dravidian languages have been used in greater numbers since the 19th century. a. also spoken in Singapore , Malaysia , South Africa , Mauritius and Réunion . Tamil is one of four official languages in Singapore. More recently, many speakers of Dravidian languages have emigrated to Europe , North America and the Gulf States .

classification

The Dravidian languages are divided into the northern group, central group and - according to speakers - the southern group, the latter being divided into South-Central Dravidian (also called South II) and the actual South Dravidian (South I) (cf.Krishnamurti 2003). Even if these terms are geographical, it is still a linguistically justifiable genetic classification. An important isogloss , according to which the subgroups can be divided, is the formation of the perfect: While the central group has received the original auxiliary verb one , in the south-central group this has been shortened or completely dropped, in the southern group one has replaced it with the auxiliary verb iru . In addition, the subgroups show phonological differences: in the South Dravidian languages, for example, the original * c- is dropped (e.g. * cāṟu "six"> Tamil āṟu ). In the south-central Dravidian group, a metathesis of apical sounds has taken place, so that sound sequences occur at the beginning of the word that are not possible in the other Dravidian languages (e.g. * varay "draw, write"> Telugu vrāyu > rāyu ). The Central-Dravidian group is characterized by an anaptic alternation in the stem syllables (e.g. Kolami teḍep "cloth", teḍp-ul "cloth"). In the North Dravidian group, the original * k was kept in front of * i , while in the other groups it was palatalized.

Cladogram

- Dravidian

- (27 languages with 223 million speakers)

- North Dravidian: (3 languages, 4.3 million speakers)

- Central Dravidian: (6 languages, 240 thousand speakers)

-

South Dravidian:

- South Dravidian i. e. S. or South I: (11 languages, 140 million speakers)

- Tulu-Koraga

- Tamil Kannada

- Toda-kota

- Tamil Kodagu

- Kodagu Korumba

- Irula

- Tamil Malayalam

- South Central Dravidian or South II: (7 languages, 78 million speakers)

- South Dravidian i. e. S. or South I: (11 languages, 140 million speakers)

More dravidian small languages, numbers of speakers

There are reports of several other minor Dravidian idioms that have not been adequately researched. It is therefore not possible to determine whether they are independent languages or just dialects of the languages classified here. In Ethnologue (2005) lists over 70 Dravidian languages. These additional “languages” are not mentioned in either Steever (1998) or Krishnamurti (2003). These are either dialects or names of tribes that speak one of the Dravidian or Indo-Aryan (!) Languages listed here.

Overall, the number of speakers is relatively uncertain, as there is often no distinction between ethnicity and language competence.

Hypotheses that the Dravidian languages are related to the language of the Indus culture or the Elamite language (see below) are not taken into account in this classification.

Linguistic characteristics

Reconstruction of the Proto-Dravidian

Using the methods of comparative linguistics , a Dravidian proto- language can be reconstructed from which all modern Dravidian languages are derived. According to glottochronological studies, a common Dravidian proto-language could have been around 4000 BC. Existed before it began to be divided into the various individual languages. The South Dravidian languages would therefore have emerged as the last branch around 1500 BC. Developed apart. Reconstruction is made more difficult by the fact that only four of the Dravidian languages are documented in writing over a longer period of time, and even with these, the tradition goes less far back than the Indo-European languages .

Typology

Typologically , the Dravidian languages belong to the agglutinating languages, i.e. they express relationships between the words through monosemantic affixes , in the case of Dravidian almost exclusively suffixes (suffixes). This means that, in contrast to inflected languages such as German or Latin, a suffix only fulfills one function and a function is only fulfilled by one suffix. For example, in Tamil the dative plural kōvilkaḷukku "the temples, to the temples" is formed by combining the plural suffix -kaḷ and the dative suffix -ukku , while in the Latin forms templo and templis the endings -o and -is are both case and number at the same time describe.

The Dravidian languages distinguish only two basic parts of speech : nouns and verbs , each of which is inflected differently. There are also undeclinable words that take on the function of adjectives and adverbs .

Phonology

The following reconstruction of the phonology ( phonology ) of Protodravidian is based on Krishnamurti: The Dravidian Languages. 2003, pp. 90-93.

Vowels

The reconstructed Phoneme inventory of Protodravidian includes five vowels , each of which occurs in a short and long form (cf. * pal "tooth" and * pāl "milk"). The diphthongs [ ai ] and [ au ] can as sequences of vowel and semivowel, ie / ay / and / av / , be construed. This results in the following vowel system for Protodravidian (given is the IPA phonetic transcription and, if different, the scientific transcription in brackets):

| front | central | back | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| short | long | short | long | short | long | |

| closed | i | iː (ī) | u | uː (ū) | ||

| medium | e | eː (ē) | O | oː (ō) | ||

| open | a | aː (ā) | ||||

Most of the Dravidian languages spoken today have retained this simple and symmetrical vowel system. In many non-written languages, however, short and long vowels only contrast in the stem syllable. Brahui has lost the distinction between short and long e under the influence of the neighboring Indo-Aryan and Iranian languages . Other Dravidian languages have additional vowel phonemes developed: [ AE ] comes in many languages in English loan words in Telugu but also in native words before. Kodava and most of the Nilgiri languages have central vowels . Tulu has the additional vowels [ ɛ ] and [ ɯ ] developed.

The word accent is only weakly pronounced in the Dravidian languages and never distinguishes meaning. Usually it falls on the first syllable.

Consonants

For the following 17 Protodravidische be consonant reconstructed up to / r / and / Z / all also doubled may occur:

| labial | dental | alveolar | retroflex | palatal | velar | glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plosives | p | t̪ (t) | t (ṯ) | ʈ (ṭ) | c | k | |

| Nasals | m | n̪ (n) | ɳ (ṇ) | ɲ (ñ) | |||

| Lateral | l | ɭ (ḷ) | |||||

| Flaps / approximants | ɾ (r) | ɻ (ẓ) | |||||

| Half vowels | ʋ (v) | j (y) | H |

What is striking about the consonant system of Protodravidian is the distinction between plosives ( plosives ) according to six articulation locations: labial , dental , alveolar , retroflex , palatal and velar . The alveolar plosive has only survived in a few languages such as Malayalam, Old Tamil, and many Nilgiri languages. In other languages süddravidischen it is between vowels for vibrants / R / become connected to the flap / r / contrasts, while these two sounds have collapsed in the other languages. As a result, most of the Dravidian languages spoken today no longer have six, but only five different places of articulation. This, and in particular the distinction between retroflex and dental plosives, is characteristic of the languages of South Asia.

Voicelessness and voicedness were not meaningful in Protodravidian . The plosives had voiceless allophones at the beginning of the word and in doubling, voiced between vowels and after nasals . In Tamil and Malayalam this applies in native words still (see. Tamil Pattam [ paʈːʌm ] "Title" and Patam [ paɖʌm ] "image"). In other languages, however, voiceless and voiced plosives contrast (z. B. / p / and / b / ). In addition Kannada, Telugu and Malayalam have as well some unwritten languages such Kolami language, Naiki and Kurukh the distinction between Lehnwörter from Sanskrit or adjacent modern Aryan languages aspirated introduced and unaspirated plosives (z. B. / p / , / P / , / b / , / B / ). This multiplies the number of consonants in these languages (for example Malayalam has 39 consonant phonemes).

The Protodravidian had four nasals. During / m / and / n / occur in all Dravidian languages, the retroflex / N / in all languages except those of süddravidischen branch for dental / n / become and also the palatal / ñ / has been preserved in all languages. In contrast, the Malayalam, analogous to the plosives, distinguishes six different nasals.

The semi-vowels / y / and / v / as well as the cash and cash / l / and / r / have remained stable in all Dravidian languages. The retroflex / L / is available in all languages except the süddravidischen branch by / l / been replaced. The retroflex approximant / Z / occurs only in Tamil and Malayalam. The protodravidische / h / only occurred in certain positions and is unique in Old Tamil as so-called āytam get -According. Where in modern Dravidian languages, a / h / occurs, it is borrowed or secondary (eg. As Kannada hogu "go" < * Poku ). It is noticeable that there was not a single sibilant in Protodravidian . The sibilants of the modern Dravidian languages are borrowed or secondary. The phonology of individual Dravidian languages has undergone special developments that cannot be discussed in detail here. Toda has an extremely complex sound system with 41 different consonants.

Alveolar and retroflex consonants could not appear at the beginning of a word in Protodravidian. Consonant clusters were only permitted to a limited extent within the word. At the end of the word plosives always followed the short auxiliary vowel / u / . In modern languages, these rules are partly overridden by loan words (e.g. Kannada prīti "love", from Sanskrit), and partly by internal sound changes.

Nominal morphology

Number and gender

The Dravidian languages have two numbers , singular and plural . The singular is unmarked, the plural is expressed by a suffix. The plural suffixes are * - (n) k (k) a (cf. Kui kōḍi-ŋga "cows", Brahui bā-k "mouths"), * -ḷ (cf. Telugu goḍugu-lu "umbrellas", Ollari ki- l “hands”) and the combination of these two * - (n) k (k) aḷ (cf. Tamil maraṅ-kaḷ “trees”, Kannada mane-gaḷ “houses”).

With regard to gender , the individual Dravidian languages have different systems. What they have in common is that the grammatical gender (gender) always corresponds to the natural gender ( sex ) of the word. In addition to individual special developments, there are three main types in which the categories "male" or "non-male" as well as "human" and "non-human" play a central role:

- The South Dravidian languages distinguish in the singular between masculine (human, male), feminine (human, non-masculine) and neuter (non-human), in the plural only between epiconum (human) and neuter (non-human).

- The central Dravidian and many south-central Dravidian languages differentiate between masculine and non-masculine in both the singular and the plural.

- Telugu and the North Dravidian languages differentiate in the singular between masculine and non-masculine, in the plural, however, between epicön and neuter.

There is no consensus as to which of these three types is the original. The demonstrative pronouns of the three languages Tamil (South Dravidian, type 1), Kolami (central Dravidian, type 2) and Telugu (south-central Dravidian, type 3) are listed as examples for the different types of pleasure systems :

| m. Sg. | f. Sg. | n. Sg. | m. Pl. | f. Pl. | n. pl. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tamil | avaṉ | avaḷ | atu | avarkaḷ | avai | |

| Kolami | at the | ad | avr | adav | ||

| Telugu | vāḍu | adi | vāru | avi | ||

The gender is not explicitly marked for all nouns. In Telugu, anna “older brother” is masculine and amma “mother” is non-masculine, without this being evident from the pure form of the word. However, many nouns are formed with certain suffixes that express gender and number. For Protodravidian, the suffixes * -an or * -anṯ can be used for the singular masculine (cf. Tamil mak-aṉ "son", Telugu tammu-ṇḍu "younger brother"), * -aḷ and * -i for the singular Feminine (cf. Kannada mag-aḷ “daughter”, Malto maq-i “girl”) and * -ar for the plural masculine or epicönum (cf. Malayalam iru-var “two people”, Kurukh āl-ar “men” ) reconstruct.

case

The Dravidian languages express case relationships with suffixes. The number of cases varies in the individual languages between four (Telugu) and eleven (Brahui). However, it is often difficult to draw a line between case suffixes and post positions .

The nominative is always the unmarked basic form of the word. The other cases are formed by adding suffixes to an obliquus stem. The Obliquus can either be identical to the nominative or be formed by certain suffixes (e.g. Tamil maram "tree": Obliquus mara-ttu ). Several obliquus suffixes can be reconstructed for Protodravidian, which are composed of the minimal components * -i- , * -a- , * -n- and * -tt- . In many languages the obliquus is identical to the genitive .

Proto-Dravidian case suffixes can be reconstructed for the three cases accusative, dative and genitive. Other case suffixes only occur in individual branches of Dravidian.

- Accusative : * -ay (Tamil yāṉaiy-ai "the elephant", Malayalam avan-e "him", Brahui dā shar-e "this village (acc.)"); * -Vn (Telugu bhārya-nu "the wife (acc.)", Gondi kōndat-ūn "the ox", Ollari ḍurka-n "the panther")

- Dative : * - (n) k (k) - (Tamil uṅkaḷ-ukku "you" Telugu pani-ki "for work", Kolami ella-ŋ "to the house")

- Genitive : - * a / ā (Kannada avar-ā "to be", Gondi kallē-n-ā "the thief", Brahui xarās-t-ā "the bull"); * -in (Tamil aracan-iṉ "the king", Toda ok-n "the older sister", Ollari sēpal-in "the girl")

Pronouns

Personal pronouns occur in the 1st and 2nd person. In the 1st person plural there is an inclusive and exclusive form, i. H. a distinction is made as to whether the person addressed is included. There is also a reflexive pronoun that relates to the subject of the sentence and corresponds in its formation to the personal pronouns. The personal and reflexive pronouns reconstructed for Protodravidian are listed in the table below. In addition, there are special developments in some languages: The south and south-central Dravidian languages have transferred the * ñ initials of the 1st person plural including to the 1st person singular (see Malayalam ñān , but Obliquus en < * yan ). The differences between the forms for the inclusive and exclusive We are partially blurred, the Kannada has completely abandoned this distinction. The languages of the Tamil Kodagu group have created a new exclusive we by adding the plural suffix (cf. Tamil nām "we (incl.)", Nāṅ-kaḷ "we (excl.)").

| Nom. | Obl. | meaning | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Sg. | * yān | * yan | I |

| 1st pl. Excl. | * yām | * yam | we (excl.) |

| 1st pl. Incl. | * ñām | * ñam | we (incl.) |

| 2nd Sg. | * nīn | * nin | you |

| 2nd pl | * nīm | * nim | her |

| Refl. Sg. | * tān | * tan | (he / she / it) himself |

| Refl. Pl. | * tām | * tam | (herself |

The demonstrative pronouns also serve as the third person's personal pronouns. They consist of an initial vowel that expresses deixis and a suffix that expresses number and gender. There are three levels of deixis: the distant deixis is formed with the initial vowel * a- , the middle deixis with * u- and the near deixis with * i- . The same deictic elements occur in local (“here”, “there”) and temporal adverbs (“now”, “then”). The original threefold distinction of deixis (e.g. Kota avn “he, that”, ūn “he, this there”, ivn “he, this one”) has only survived in a few languages spoken today. Interrogative pronouns are formed analogously to the demonstrative pronouns and are identified by the initial syllable * ya- (e.g. Kota evn "which").

Numerals

Community Dravidian roots can be reconstructed for the basic numbers up to “one hundred”. Only Telugu ( vēyi ) has a native numeral for “thousand” . The other Dravidian languages have borrowed their numeral for “thousand” from Indo-Aryan (Tamil, Malayalam āyiram , Kannada sāvira , Kota cāvrm < Prakrit * sāsira <Sanskrit sahasra ). The numerals for “one hundred thousand” and “ten million”, which can be found in the Dravidian languages as in the other languages of South Asia (see Lakh and Crore ) , also come from Sanskrit . Many of the Dravidian tribal languages of central and north India have adopted numerals from the neighboring non-Dravidian languages on a large scale. B. in Malto only "one" and "two" of Dravidian origin.

The Dravidian numerals follow the decimal system , i.e. H. Composite numbers are formed as multiples of 10 (e.g. Telugu ira-vay okaṭi (2 × 10 + 1) "twenty-one"). A special feature of the South Dravidian languages is that the numerals for 9, 90 and 900 are derived from the next higher unit. In Tamil, oṉ-patu “nine” can be analyzed as “one less than ten” and toṇ-ṇūṟu “ninety” as “nine (tenths) of a hundred”. Kurukh and Malto have developed a vigesimal system with 20 as a base under the influence of neighboring Munda languages (e.g. Malto kōṛi-ond ēke (20 × 1 + 1) "twenty-one").

| number | Protodravidian | Tamil | Malayalam | Kannada | Telugu |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | * onṯu | oṉṟu | onnu | ondu | okaṭi |

| 2 | * iraṇṭu | iraṇṭu | raṇṭu | eraḍu | reṇḍu |

| 3 | * mūnṯu | mūṉṟu | mūnnu | mūru | mūḍu |

| 4th | * nālnk (k) V | nāṉku | nālu | nālku | nālugu |

| 5 | * caymtu | aintu | añcu | aitu | aidu |

| 6th | * cāṯu | āṟu | āṟu | āru | āru |

| 7th | * ēẓ / * eẓV | ēẓu | ēẓu | ēḷu | ēḍḍu |

| 8th | * eṇṭṭu | eṭṭu | eṭṭu | eṇṭu | enimidi |

| 9 | * toḷ / * toṇ | oṉpatu | onpatu | ombattu | tommidi |

| 10 | * pahtu | pattu | pattu | hattu | padi |

| 100 | * nūṯ | nūṟu | nūṟu | nūru | nūru |

Verbal morphology

The Dravidian verb is formed by adding suffixes for tense and mode as well as personal suffixes to the root of the word . The Tamil word varukiṟēṉ “I come” is composed of the verb stem varu- , the present tense suffix -kiṟ and the suffix of the 1st person singular -ēṉ . In Proto-Dravidian there are only two tenses, past and non-past, while many daughter languages have developed a more complex tense system. The negation is expressed synthetically through a special negative verb form (cf. Konda kitan "he made", kiʔetan "he did not"). The verb stem can be modified in many Dravidian languages with stem-forming suffixes. Malto derives from the stem nud- "hide" the reflexive verb stem nudɣr- "hide".

Infinite verb forms are dependent on either a following verb or a following noun. They are used to form more complex syntactic constructions. In Dravidian verbal compounds can be formed, so the Tamil konṭuvara “bring” is composed of an infinite form of the verb koḷḷa “hold” and the verb vara “to come”.

syntax

A fixed word sequence subject-object-verb (SOV) is characteristic of the Dravidian languages . Accordingly, the subject is in the first place in the sentence (it can only be preceded by circumstances of time and place) and the predicate always at the end of the sentence. As is characteristic of SOV languages, in the Dravidian languages attributes always come before their reference word, subordinate clauses before main clauses, full verbs before auxiliary verbs and postpositions are used instead of prepositions . Only in the North Dravidian languages has the rigid SOV word sequence been relaxed.

A simple sentence consists of a subject and a predicate, which can be either a verb or a noun. There is no copula in Dravidian. The subject is usually in the nominative, in many Dravidian languages the subject is also in the dative in a sentence that expresses a feeling, a perception or a possession. In all Dravidian languages except Malayalam, a verbal predicate is congruent with a nominative subject. Kui and Kuwi developed a system of congruence between object and verb. In some Dravidian languages (Old Tamil, Gondi) a nominal predicate also takes on personal endings. Examples of simple sentences from Tamil with interlinear translation :

- avar eṉṉaik kēṭṭār. (he asked me) "He asked me." (nominative subject, verbal predicate)

- avar eṉ appā. (he my father) "He is my father." (subject in the nominative, nominal predicate)

- avarukku kōpam vantatu. (Anger came to him) "He became angry." (Subject in the dative, verbal predicate)

- avarukku oru makaṉ. (for him a son) "He has a son." (subject in the dative, nominal predicate)

Complex sentences consist of a main clause and one or more subordinate clauses . In general, a sentence can only contain one finite verb. The Dravidian languages have no conjunctions ; subordinate clauses, like parataxes, are formed by infinite verb forms. These include the infinitive , the verbal participle , which expresses a sequence of actions, and the conditional , which expresses a condition. Relative clauses correspond to constructions with the so-called adnominal participles. Examples from Tamil with interlinear translation:

- avarai varac col. (tell him to come) "Tell him to come." (Infinitive)

- kaṭaikku pōyi muṭṭaikaḷ koṇṭuvā. (going to the shop-having brought eggs) "Go to the shop and bring eggs." (verbal participle)

- avaṉ poy coṉṉāl ammā aṭippāḷ. (he lies when-saying mother will-hit) "If he lies, mother will hit him." (conditional)

- avaṉ coṉṉatu uṇmai. (he says truth) "What he says is true." (adnominal participle)

These constructions are not possible for subordinate clauses with a nominal predicate, since no infinite forms can be formed for a noun. Here you can use the so-called quotative verb (usually an infinite form of “say”), through which the nominal subordinate clause is embedded in the sentence structure. Example from Tamil with interlinear translation:

- nāṉ avaṉ nallavaṉ eṉṟu niṉaikkiṟēṉ. (I think he is saying good) "I think he is a good man."

vocabulary

Word roots seem to have been monosyllabic in Protodravidian as a rule. Protodravidian words could be simple, derived, or compound . Iterative compounds could be formed by doubling a word, cf. Tamil avar "he" and avaravar "everyone" or vantu "coming" and vantu vantu "always coming back". A special form of the reduplicated compound words are the so-called echo words, in which the first syllable of the second word is replaced by ki , cf. Tamil pustakam "book" and pustakam-kistakam "books and the like". The number of verbs is closed in Dravidian. New verbs can only be formed from noun-verb compounds, e.g. B. Tamil vēlai ceyya “work” from vēlai “work” and ceyya “make”.

In addition to the inherited Dravidian vocabulary, today's Dravidian languages have a large number of words from Sanskrit or later Indo-Aryan languages. In Tamil they make up a relatively small part in the early 20th century, not least due to specific language-puristic tendencies, while in Telugu and Malayalam the number of Indo-Aryan loanwords is large. In Brahui, which, due to its distance from the other Dravidian languages, was strongly influenced by its neighboring languages, only a tenth of the vocabulary is of Dravidian origin. More recently, like all languages of India, the Dravidian languages have borrowed words from English on a large scale ; loanwords from Portuguese are less numerous .

Dravidian words that have found their way into German are " orange " (via Sanskrit nāraṅga, cf. Tamil nāram ), " catamaran " (Tamil kaṭṭumaram "[boat made of] bound tree trunks"), " mango " (Tamil māṅkāy, Malayalam māṅṅa ), “ Manguste ” and “ Mungo ” (Telugu muṅgisa, Kannada muṅgisi ), “ Curry ” (Tamil kaṟi ) and possibly “ Kuli ” (Tamil kūli, “wage”). The word glasses is probably derived from the name of the mineral beryl from a Dravidian etymon .

Some dravidian word equations

| language | fish | I | below | come | one) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proto-Drawid. | * mīn | * yān | * kīẓ ~ kiẓ | * varu ~ vā | * ōr ~ or ~ on |

| Tamil | mīṉ | yāṉ, nāṉ | kīẓ | varu, vā- | oru, ōr, okka |

| Malayalam | mīn | ñān | kīẓ, kiẓu | varu, vā- | oru, ōr, okka |

| Irula | nā (nu) | kiye | varu | or- | |

| Kota | mīn | on | kī, kīṛm | vār-, va- | ōr, o |

| Toda | mīn | ōn | kī | pōr-, pa- | wïr, wïd, oš |

| Badaga | mīnu | nā (nu) | kīe | bā-, bar | ondu |

| Kannada | mīn | nānu | kīẓ, keḷa | ba-, bāru- | or, ōr, ondu |

| Kodagu | mini | nānï | kï ;, kïlï | bar-, ba- | orï, ōr, onï |

| Tulu | mīnɯ | yānu, yēnu | kīḷɯ | barpini | or, oru |

| Telugu | mīnu | ēnu, nēnu | kri, k (r) inda | vaccu, rā- | okka, ondu |

| Gondi | mīn | anā, nanna | vaya | or-, undi | |

| Conda | mīn | nān (u) | vā-, ra- | or-, unṟ- | |

| Kui | mīnu | ānu, nānu | vāva | ro- | |

| Kuwi | mīnu | nānu | vā- | ro- | |

| Manda | on | vā- | ru- | ||

| Pengo | ān, āneŋ | vā- | ro- | ||

| Kolami | on | var-, vā | OK- | ||

| Parji | mini | on | kiṛi | ver | OK- |

| Gadaba | mīn | on | var- | uk- | |

| Malto | mīnu | ēn | bare | place-, -ond | |

| Kuruch | ēn | kiyyā | barnā- | place, on | |

| Brahui | ī | ki-, kē- | bar-, ba- | asiṭ, on- |

Fonts

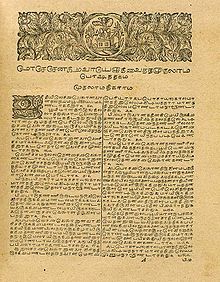

Of the Dravidian languages, only the four major languages Telugu, Tamil, Kannada and Malayalam are established written languages. Each of these has its own script: the Telugu script , Tamil script , Kannada script and Malayalam script . Like the scriptures of North India, Tibet and Southeast Asia, they belong to the family of Indian scripts . These all come from the 3rd century BC. Documented Brahmi script, the origins of which are unclear. The Dravidian scripts differ from the North Indian scripts in that they have some additional characters for sounds that are not found in the Indo-Aryan languages. The Tamil script is also characterized by the fact that, due to the phonology of Tamil, it does not have any characters for voiced and aspirated consonants and the character inventory is therefore significantly reduced. In addition, unlike all other Indian scripts, it does not use ligatures for consonant clusters , but a special diacritical mark.

For the other Dravidian languages, if they are written at all, the script of the respective regional majority language is usually used, e.g. the Kannada script for Kodava , the Devanagari script for Gondi or the Persian-Arabic script , which is also used for the other languages of Pakistan Scripture for Brahui .

- The sign ka in the Dravidian scriptures

Research history

There is an ancient indigenous grammar tradition in India. Both Tamil and Sanskrit grammar have roots that go back over 2000 years. As for the relationship between Tamil and Sanskrit, there were two contradicting views in South India: one emphasized the independence and equality of Tamil, which, like Sanskrit, was viewed as a "divine language", the other held Tamil a falsification of the "sacred" Sanskrit.

After Vasco da Gama was the first European seafarer to land in Calicut in 1498 , European missionaries first came into contact with the Tamil- and Malayalam-speaking parts of southern India in the 16th century. The first European scholar who studied the Dravidian languages in depth was the Portuguese Jesuit Anrique Anriquez (c. 1520–1600). He wrote a Tamil grammar in 1552, had the first Tamil book printed in 1554 and wrote other Tamil-language literature with religious content.

William Jones , who in 1786 recognized the relationship between Sanskrit, Greek and Latin and thus founded Indo-European studies , considered all contemporary Indian languages to be unrelated to Sanskrit. It was later discovered that Hindi and the other modern Indo-Aryan languages are related to Sanskrit, but now they went over the top, as it were, and the Dravidian languages were also believed to be descendants of Sanskrit.

The Englishman Francis Whyte Ellis , who worked as a colonial official in Madras , dealt with Tamil and in his foreword to the first Telugu grammar published in 1816 noted for the first time a relationship between Tamil, Telugu, Kannada, Malayalam, Tulu, Kodagu and Malto, which he summarized as "Dialects of South India". In 1844 the Norwegian indologist Christian Lassen recognized that Brahui was related to the South Indian languages. The recognition of the independence of the Dravidian languages finally prevailed with the comparative grammar of the Dravidian languages by the Englishman Robert Caldwell published in 1856 . The term “Dravidian” also comes from Caldwell (previously there was talk of “ Dekhan languages” or simply “South Indian dialects”). He used the Sanskrit word drāvi , a as a template for the term, which the Indian writer Kumarila Bhatta used to describe the South Indian languages as early as the 7th century. Etymologically, drāviḍa is probably related to tamiḻ , the proper name for Tamil.

In the next 50 years after Caldwell, no great advances in the study of the Dravidian languages followed. Indology focused almost entirely on Sanskrit, while Western scholars studying Dravidian languages mainly limited themselves to compiling dictionaries. The fourth volume of the Linguistic Survey of India , published in 1906, was devoted to the Munda and Dravidian languages and heralded a second active phase in Dravidian linguistics. In the period that followed, numerous new Dravidian languages were discovered, and studies were carried out for the first time on the relationship between Dravidian and other language families and the linguistic contacts between Indo-Aryan and Dravidian languages. Jules Bloch published a synthesis in 1946 entitled Structure grammaticale des langues dravidiennes . In the period that followed, researchers such as Thomas Burrow , Murray B. Emeneau , Bhadriraju Krishnamurti , PS Subrahmanyam , N. Kumaraswami Raja , SV Shanmugan , Michail Sergejewitsch Andronow or Kamil V. Zvelebil dealt with the Dravidian languages. In the second half of the 20th century, the terms Dravidian and Tamil studies became common for Dravidian and Tamil philology . Some universities have included Dravidian languages, mostly Tamil, in their courses, in German-speaking countries for example the universities of Cologne , Heidelberg and Berlin (Telugu at Humboldt University).

Relationships with other languages

According to the current state of research, the Dravidian languages are not demonstrably related to any other language family in the world. They show numerous similarities with the other languages of South Asia, which, however, are undoubtedly not based on genetic relationship , but on mutual rapprochement through millennia of language contact . A possible relationship with the language of the Indus culture , known as "Harappan", could not be proven, because the Indus script has not yet been deciphered. Over the past century and a half there have been a multitude of attempts to establish links between the Dravidian languages and other languages or language families. Of these, the theories of a kinship with the Elamite language and the Uralic language family are the most promising, although they have not been conclusively proven.

South Asian language federation

The languages native to South Asia belong to four different language families. Besides the Dravidian languages, these are the Indo-European ( Indo-Aryan and Iranian subgroup), Austro-Asian ( Munda and Mon-Khmer subgroup) and Sino-Tibetan ( Tibeto-Burmese subgroup) language families. Although these four language families are not genetically related, they have come so close to one another through language contact over thousands of years that one speaks of a South Asian language union.

The Dravidian languages share all of the important characteristics that make up this linguistic union. The Dravidian languages seem to have had a strong typological (e.g. compound nouns , verbal participles ) and also phonological (e.g. the presence of retroflexes , simplification of the consonant clusters in Central Indo-Aryan) influence on the Indo-Aryan languages. In return, the Dravidian languages have largely adopted vocabulary from Sanskrit and other Indo-Aryan languages, which in some cases also had an impact on their phonology (phoneme status of the aspirated consonants).

Dravidian and Harappan

The language of the Indus or Harappa culture , an early civilization that spread between 2800 and 1800 BC. BC in the Indus valley in the northwest of the Indian subcontinent is unknown. It has come down to us in a series of inscriptions on seals that are written in the as yet undeciphered Indus script . Since the discovery of the Indus script in 1875, numerous attempts have been made to decipher the script and identify the Harappan language. The hypothesis has often been expressed that the bearers of the Indus culture spoke a Dravidian language. As an indication of this, it is stated that a Dravidian language is also spoken today in Pakistan with Brahui and that the Dravidian language area probably extended much further north before the Indo-Aryan languages penetrated.

In 1964, two research teams, one in the Soviet Union and one in Finland, independently began a computer-aided analysis of the Indus script. Both concluded that the language was Dravidian. This thesis is based on a structural analysis of the inscriptions, which seems to suggest that the language of the inscriptions was agglutinating. Asko Parpola , head of the Finnish research group, has been claiming since 1994 to have at least partially deciphered the Indus script. He relies on the rebus principle and cases of homonyms . Thus, for example, a symbol representing a fish would stand for the sequence of sounds * mīn , which in Proto-Dravidian can mean both "fish" and "star".

However, because no bilingual texts are known and the corpus of the Harappan inscriptions is limited, a complete decipherment of the Indus script seems difficult or even impossible. Some researchers even deny that the characters are actually writing. The question of whether the carriers of the Indus culture belonged to a Dravidian language group wins as part of a Tamil - nationalist discourse a special political Sharpness: Here, the strain of the domains of the Dravidian and the Indus culture often seems to be necessary for a determination of identity modern Tamilität while North Indian researchers claim that the language of the Indus script was an archaic form of Sanskrit . However, most researchers consider the relationship between Harappan and the Dravidian languages to be a plausible, albeit unproven, hypothesis.

Dravidian and Elamite

As early as 1856, RA Caldwell suspected in his comparative grammar a relationship between the Dravidian languages and Elamite . The Elamite language was spoken in southwest Iran from the 3rd to the 1st millennium BC and is considered an isolated language , i.e. H. a language with no proven relatives. In the 1970s, the American researcher David W. McAlpin took up this theory again and published a monograph in 1981 in which he claimed to have proven the Elamite-Dravidian relationship. The Elamite-Dravidian hypothesis is based on the one hand on structural similarities (both languages are agglutinative and have parallels in the syntax), on the other hand, McAlpin pointed out a number of similar suffixes and established 81 Elamish-Dravidian word equations. According to McAlpin's hypothesis, Elamish and Dravidian belonged to a common language family, which is also known as “Zagrosian” after their assumed original home in the Zagros Mountains, and would have changed between 5500 and 3000 BC. Chr. Separated from each other.

From the point of view of most other researchers, however, McAlpin's evidence is insufficient to demonstrate a genetic relationship. Zvelebil 1991 speaks of an "attractive hypothesis" for which there is a lot of evidence but no evidence. Steever 1998 considers McAlpin's thesis to be dubious.

Dravidian and Ural

The theory of the relationship between the Dravidian and Uralic languages, a family that includes Finnish , Estonian and Hungarian , also goes back to R. A. Caldwell, who in 1856 believed that there were "remarkable similarities" between the Dravidian and Finnish- Having established Ugric languages. Subsequently, a large number of researchers supported this thesis.

The Dravidian-Uralic theory is based on a number of matches in the vocabulary of the Dravidian and Uralic languages, similarities in phonology and, above all, structural similarities: Both language families are agglutinative, probably originally had no prefixes, and have the same order of suffixes for nouns and verbs on, have an SOV word order and put attributes in front of their reference word. While some researchers believe that the Dravidian and Uralic languages have a common origin, others argue that language families were in contact with and influenced each other in prehistoric times in Central Asia .

The problem with the Dravidian-Uralic hypothesis is that it is mainly based on typological similarities, which are not sufficient to prove a genetic relationship . Thus it cannot be considered certain either, but it is considered by some to be the most probable of the theories which attempt to connect the Dravidian languages with other language families. However, this hypothesis is rejected by many specialists in the Ural languages and has also recently been heavily criticized by Dravidian linguists such as Bhadriraju Krishnamurti.

Dravidian and Nostratic

While the binary relationship between Dravidian and Uralian is hardly accepted today, intensive work is being carried out on a more comprehensive hypothesis: Aharon Dolgopolsky and others understand Dravidian as a sub-unit of the nostratic macro family , which is supposed to include other Eurasian language families in addition to Ural:

-

Nostratic

- Indo-European

- Kartwelisch

- Ural-Jukagir

- Turkish

- Mongolian

- Tungusian

- Korean

- Japanese (?)

- Afro-Asian

- Elamish

- Dravidian

Today the Afro-Asian is hardly counted as part of the Nostratic; recently Elamish has been seen as a separate component of the Nostratic, which is not closely related to the Dravidian. Needless to say, almost all dravidologists reject the nostratic hypothesis. The 124 nostratic word equations compiled in Dolgopolsky 1998 - about half of them contain Dravidian references - are qualified as accidental similarity , loan word , wandering word , misinterpretation , non-proto-Dravidian or the like. One will have to wait and see whether the hypothetical macro-families, which go back into a much greater time depth than their branches, ever acquire the status of a widely accepted doctrine. It is interesting in this context that the Dravidian is expressly not part of the Eurasian macro family suggested by Joseph Greenberg as an alternative .

An example of a nostratic word equation with a Dravidian reference can be found in the article Nostratic .

Sources and further information

literature

Dravidian languages

- Michail S. Andronov: A Comparative Grammar of the Dravidian Languages. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2003, ISBN 3-89586-705-5 .

- Ernst Kausen: The language families of the world. Part 1: Europe and Asia. Buske, Hamburg 2013, ISBN 978-3-87548-655-1 . (Chapter 13)

- Bhadriraju Krishnamurti: The Dravidian Languages. University Press, Cambridge 2003, ISBN 0-521-77111-0 .

- Sanford B. Steever (Ed.): The Dravidian Languages. Routledge, London 1998, ISBN 0-415-10023-2 .

- Sanford B. Steever: Tamil and the Dravidian Languages. In: Bernard Comrie (Ed.): The Major Languages of South Asia, the Middle East and Africa. Routledge, London 1990, ISBN 0-415-05772-8 , pp. 231-252.

- Kamil V. Zvelebil: Dravidian Linguistics. An Introduction. Pondicherry Institute of Linguistics and Culture, Pondicherry 1990, ISBN 81-85452-01-6 .

External relationships

- Aharon Dolgolpolsky: The Nostratic Macrofamily and Linguistic Palaeontology. The McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, Oxford 1998, ISBN 0-9519420-7-7 .

- David MacAlpin: Proto-Elamo-Dravidian: the Evidence and its Implications. Dissertation . Philadelphia 1981, ISBN 0-87169-713-0 .

- Georgij A. Zograph: The languages of South Asia. Translated by Erika Klemm. VEB Verlag Enzyklopädie, Leipzig 1982, DNB 830056963 .

Web links

- Ernst Kausen: The classification of the Dravidian languages. (DOC; 71 kB)

- Ernst Kausen: Some Dravidian word equations. (DOC; 32 kB)

Individual evidence

- ^ Kamil V. Zvelebil: Dravidian Linguistics. An Introduction. Pondicherry 1990, p. 48.

- ↑ Bhadriraju Krishnamurti: The Dravidian Languages. Cambridge 2003, p. 5.

- ^ Krishnamurti: The Dravidian Languages. Pp. 6-15.

- ↑ George A. Zograph: The languages of South Asia. Leipzig 1982, p. 95.

- ^ Krishnamurti: The Dravidian Languages. P. 6.

- ↑ Sanford B. Steever: Introduction to the Dravidian Languages. In: Sanford B. Steever (Ed.): The Dravidian Languages. London 1998, p. 11.

- ↑ Krishnamurti 2003, pp. 213-215.

- ↑ Krishnamurti 2003, pp. 205-212.

- ↑ Krishnamurti 2003, pp. 215-217.

- ↑ On the problem of the case using the example of Tamil, see Harold F. Schiffman: The Tamil Case System . In: Jean-Luc Chevillard (Ed.): South-Indian Horizons: Felicitation Volume for François Gros on the occasion of his 70th birthday. Publications du Département d'Indologie 94. Pondichéry: Institut Français de Pondichéry, 2004. pp. 301–313.

- ↑ Krishnamurti 2003, pp. 217-227.

- ↑ Krishnamurti 2003, pp. 227-239.

- ↑ Krishnamurti 2003, pp. 244-253.

- ↑ Krishnamurti 2003, pp. 253-258.

- ↑ Krishnamurti 2003, pp. 258-266.

- ↑ Josef Elfenbein: Brahui. In: Sanford B. Steever (Ed.): The Dravidian Languages. London 1998, p. 408.

- ↑ The examples come from Steever: Introduction to the Dravidian Languages. P. 27.

- ^ Zvelebil: Dravidian Linguistics. P. Xx.

- ↑ Colin P. Masica: The Indo-Aryan Languages. Cambridge 1991, p. 3.

- ^ Zvelebil: Dravidian Linguistics. P. xxi

- ^ Asko Parpola: Deciphering the Indus Script . University Press, Cambridge 1994. See also: Study of the Indus Script. ( Memento of the original from March 6, 2006 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. 2005. (PDF file; 668 kB)

- ↑ Steve Farmer, Richard Sproat, Michael Witzel: The Collapse of the Indus-Script Thesis: The Myth of a Literate Harappan Civilization. In: Electronic Journal of Vedic Studies. 11-2, 2004, pp. 19-57. (PDF file; 1.33 MB)

- ↑ On this, cf. a critical discussion of corresponding points of view by Iravatham Mahadevan : Aryan or Dravidian or Neither? A Study of Recent Attempts to Decipher the Indus Script (1995-2000). ( Memento of February 5, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) In: Electronic Journal Of Vedic Studies. 8/2002. (PDF)

- ^ SR Rao: The decipherment of the Indus script. Asia Publ. House, Bombay 1982.

- ^ Zvelebil: Dravidian Linguistics. P. 97; Steever: Introduction to the Dravidian Languages. P. 37.

- ^ David W. McAlpin: Proto-Elamo-Dravidian: The Evidence and its Implications . Philadelphia 1981.

- ^ Zvelebil: Dravidian Linguistics. P. 105.

- ↑ Steever: Introduction to the Dravidian Languages. P. 37.

- ^ Zvelebil: Dravidian Linguistics. P. 103.

- ↑ Kamil Zvelebil: Comparative Dravidian Phonology. Mouton, The Hague, OCLC 614225207 , S. 22ff (contains a bibliography of articles supporting and opposing the theory)

- ↑ Bhadriraju Krishnamurti : The Dravidian Languages. Cambridge University Press, 2003, ISBN 0-521-77111-0 , p. 43.