Hindi

| Hindi ( हिन्दी ) | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Spoken in |

India | |

| speaker | 370 million native speakers , 155 million second speakers (estimated) |

|

| Linguistic classification |

||

| Official status | ||

| Official language in | India , states: | |

| Language codes | ||

| ISO 639 -1 |

Hi |

|

| ISO 639 -2 |

down |

|

| ISO 639-3 |

down |

|

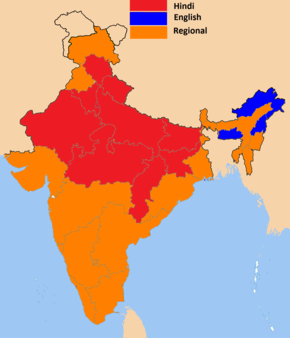

Hindi ( हिन्दी hindī / ɦind̪iː / ) is an Indo-Aryan , thus Indo-Iranian and Indo-European language at the same time , which is spoken in most of the north and central Indian states and is derived from the Prakrit languages . It has been the official language of India (along with English ) since 1950 . Hindi is closely related to Urdu .

Among the most widely spoken languages in the world , Hindi ranks third after Chinese and English, ahead of Spanish . Over 600 million people in and around India use it as their mother tongue or everyday language . In Fiji , more than a third of the population speaks Fiji Hindi , in Guyana and Suriname a minority, although it is rapidly losing speakers, especially in Guyana ( Surinamese Hindi is sometimes considered to be a single language).

Hindi is in Devanagari written and contains many book words from Sanskrit . In contrast, Urdu , the official language of Pakistan, is written with Arabic characters and has incorporated many words from the Persian , Turkish and Arabic languages . Both are varieties of Hindustani .

The use of words from different origins has long been the subject of national political endeavors. Hindu nationalists systematically replace words of Arabic origin with borrowings from Sanskrit in order to emphasize their cultural independence. There were similar efforts to promote Sanskrit in the form of Popular Sanskrit. There are also a variety of local dialects of Hindi.

etymology

The word hindī is of Persian origin and means "Indian". It was originally used by pre-Islamic Persian merchants and ambassadors in northern India to refer to the predominant language of northern India, Hindustani . It was later used at the Mughal court to distinguish the local language of the Delhi region from Persian , the official language of the court at the time.

development

origin

As for many other Indian languages, Hindi is also believed to have developed from Prakrit via the so-called Apabhramsha . Hindi emerged as a local dialect, like Braj , Awadhi and finally Khari Boli after the turn of the 10th century.

Compared to Sanskrit, the following changes have occurred, some of which can already be found in Pali :

- frequent omission of final 'a' and other vowels ( shabda- > shabd 'word')

- Failure of 'r' in some connections ( trīni > tīn 'three')

- Reduction of consonant clusters ( sapta > sāt 'seven')

- Failure of nasal consonants with remaining nasalization ( shānta- > shā̃t 'calm').

Persian and Arab influence

In 1000 years of Islamic influence, many Persian and Arabic words found their way into the Khari Boli. Since almost all Arabic loanwords were taken from Persian, they did not retain the original Arabic phonetic state.

Portuguese loanwords

From Portuguese, some loan words can still be found in Hindi today; the Portuguese phonetic level can be used well in Hindi, as in mez < mesa 'table', pãv < pão 'bread', kamīz < camisa 'shirt'.

English loanwords

Many English-derived words are used in Hindi today, such as ball, bank, film hero, photo. However, some of them are hardly used in today's English. Due to older and more recent borrowings as well as purely Indian new formations, a large number of synonyms have arisen for some terms: leṭrīn < latrine = urinal = ṭoileṭ 'toilet' (there are also the words peshāb-khānā, pā-khānā and die, which originally came from Persian formal expressions svacchālaya, shaucālaya ).

Many older borrowings have already been adapted to the Indian phonetic system, including:

- boṭal < bottle 'bottle'

- kampyūṭar < computer

- ãgrezī < English

- pulis < police 'police'

- reḍiyo < radio

- prafessary < professor .

Above all, the dentals were colored in Hindi retroflex , which is easy to hear when Indians speak English.

Some English loanwords have been combined with Indian words to form new terms: photo khī̃cnā 'photograph', fry karnā 'roast', shark- machlī 'shark'.

Hindi as a donor language

Words from Hindi have also found their way into other languages, with Hindi partly being the original language and partly just an intermediary language. The Hindi words in German include: bungalow ( bãglā ), chutney , jungle , kajal , cummerbund , monsoon (whereby the Hindi word mausam itself is a loan word from Arabic), punch , shampoo ( cāmpnā , 'massaging'), veranda .

Varieties and registers

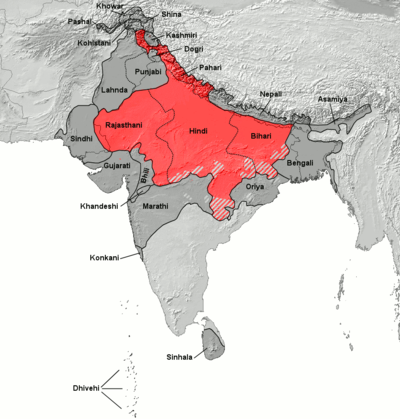

The Hindi languages in the broadest sense with all dialects of the Hindi belt - including Maithili (12 million) and Urdu (51 million) - comprise 486 million native speakers (2001 census). They can be broken down as follows:

- Central zone

- Western Hindi (middle western zone)

- 258 M: Khari Boli

- (52 M: Urdu , counted separately in the public census)

- 8 M: Haryanvi

- 6 M: Kanauji

- Eastern Hindi (Middle Eastern Zone)

- 20 M: Avadhi

- 11 M: Chhattisgarhi

- 18 M: Rajasthani

- Western Hindi (middle western zone)

- Bihari (eastern zone)

- 7 M: Pahari (northern zone) (without Dogri and Nepali)

Khari boluses

Khari boli is the term for the West Indian dialect of the Delhi region, which has developed into a prestigious dialect since the 17th century. Khari boli comprises several standardized registers, including:

- Urdu, historically the "language of the court", a register influenced by Persian

- Rekhta, a register subject to strong Persian and Arab influence

- Dakhni, the historical literary register of the Deccan region

- Standard Hindi, a 19th century register with a strong Sanskrit influence during the colonial era as a contrast to Urdu in the Hindi-Urdu controversy.

Modern standard Hindi

After India gained independence, the Indian government made the following changes:

- Standardization of Hindi grammar: In 1954 the government set up a committee for the creation of Hindi grammar, the report of which was published in 1958 as "A Basic Grammar of Modern Hindi", a basic grammar of Hindi.

- Standardization of orthography.

- Standardization of the Devanagari script by the 'Central Hindi Directorate of the Ministry of Education and Culture' to standardize and improve the characters.

- scientific method for transcribing the Devanagari alphabet

- Inclusion of diacritical marks to represent sounds from other languages.

Phonology and Script

In addition to 46 phonemes that come from classical Sanskrit , Hindi also includes seven additional phonemes for words that come from Persian or Arabic.

The transliteration takes place in the system IAST (International Alphabet of Sanskrit Transliteration), ITRANS, and IPA.

Vowels

The inherent vowel ( schwa / ə /), which is originally contained in every syllable, is often omitted in Hindi when written in Devanagari (Indian script), especially at the end of the word, but often also inside the word. Example: मकान (the house) is not pronounced makāna , but makān .

| Devanāgarī | Diacritical mark with “प्” | pronunciation | Pronunciation with / p / | IAST | ITRANS | German |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| अ | प | / ə / | / pə / | a | a | short or long Schwa : like e in old e |

| आ | पा | / ɑː / | / pɑː / | - | A. | long open back unrounded vowel : as a in V a ter |

| इ | पि | / i / | / pi / | i | i | short close front unrounded vowel : as i in s i nts |

| ई | पी | / iː / | / piː / | ī | I. | long unrounded closed front tongue vowel : as ie in Sp ie l |

| उ | पु | / u / | / pu / | u | u | short closed back rounded vowel : like u in H u nd |

| ऊ | पू | / uː / | / puː / | ū | U | long closed back rounded vowel : like u in t u n |

| ए | पे | / eː / | / peː / | e | e | long, unrounded, semi-closed front tongue vowel : like e in d e m |

| ऐ | पै | / æː / | / pæː / | ai | ai | long near-open front unrounded vowel : as similar in ä similar |

| ओ | पो | / οː / | / poː / | O | O | long rounded semi-closed back vowel : as o in r o t |

| औ | पौ | / ɔː / | / pɔː / | ouch | ouch | long open-mid back rounded vowel : as o in S o nne, but long. |

| ऋ | पृ | / ɻˌ / | / pɻˌ / | ṛ | R. | short syllabic voiced retroflex approximant like a vowel: like ri in English ri ng (original pronunciation is lost) |

Consonants

| labial | Labiodental | Dental | Retroflex | Palatal | Velar | Pharyngeal | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plosives | unaspirated | p प / pə / |

b ब / bə / |

t त / t̪ə / |

d द / d̪ə / |

ṭ ट / ʈə / |

ḍ ड / ɖə / |

c च / tʃə / |

j ज / dʒə / |

k क / kə / |

g ग / gə / |

|||

| aspirated | ph फ / pʰə / |

bh भ / bʱə / |

th थ / t̪ʰə / |

dh ध / d̪ʱə / |

ṭh ठ / ʈʰə / |

ḍh ढ / ɖʱə / |

ch छ / tʃʰə / |

jh झ / dʒʱə / |

kh ख / kʰə / |

gh घ / gʱə / |

||||

| Nasals | m म / mə / |

n न / nə / |

ṇ ण / ɳə / |

ñ ञ / ɲə / |

ṅ ङ / ŋə / |

|||||||||

| Half vowels | v व / ʋə / |

y य / jə / |

||||||||||||

| Approximants | l ल / lə / |

r र / rə / |

||||||||||||

| Fricatives | s स / sə / |

ṣ ष / ʂə / |

ś श / ʃə / |

ḥ ः / hə / |

h ह / ɦə / |

|||||||||

There is also the Anusvara (ṃ ं), which indicates either the nasalization of the preceding vowel or a nasal homorganous to the following consonant , and the Chandrabindu (ँ).

Consonants for words of Persian and Arabic origin

Except for ṛa and ṛha, all these consonants come from Persian or Arabic, they are more common in Urdu. Hindi speakers from rural backgrounds often confuse these consonants with the Sanskrit consonants.

| Devanagari | Transliteration | IPA | German | Confused with: |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| क़ | qa | qə | ( Voiceless uvular plosive ) Arabic: Q ur'an | / k / |

| ख़ | kh a | χə od xə | ( Voiceless velar fricative ) German: do ch | / kʰ / |

| ग़ | ġa | ʁə od ɣə | ( Voiced velar fricative ) Dutch: G ent | / g / |

| ज़ | za | zə | ( Voiced alveolar fricative ) German: S ee | / dʒ / |

| ड़ | ṛa | ɽə | (unaspirated voiced retroflex flap ) | |

| ढ़ | ṛha | ɽʱə | (aspirated voiced retroflex flap ) | |

| फ़ | fa | fə | ( Voiceless labiodental fricative ) German: f inden | / pʰ / |

The pronunciation of these so-called Nukta variants varies greatly in linguistic usage, as many speakers pronounce the phonemes as if they were written without the additional period (Nukta) (e.g. philm instead of film). There is also the opposite form in which the ph is pronounced like f.

Grammar of Hindi and Urdu

In terms of grammar, Hindi has a number of fundamental differences from the older Indian languages such as Sanskrit and Pali , which are much more formal: Sanskrit and Pali, for example, each have eight cases , while there are only three in Hindi; most relationships in the sentence must now prepositions are expressed. The dual no longer existed in Pali ; the gender neuter was also replaced by masculine and feminine; all that remains are individual shapes such as kaun ?; koī 'who ?; someone '(animated) opposite kyā ?; kuch 'what ?; something '(inanimate). Most verb forms are composed of the verb stem or participle and one or more auxiliary verbs . Hindi has thus moved far away from the formerly pure type of an inflected language .

For transcription

The IAST standard is used here for transcription, which also applies to other Indian languages such as Sanskrit, with some special characters for special Hindi sounds (such as f, q and x ):

- Vowels:

offene Vokale: a ai i au u (ursprüngliche kurze Vokale bzw. Diphthonge) geschlossene Vokale: ā e ī o ū (ursprüngliche Langvokale)

Die Tilde (~) steht für Anusvāra (der davor oder darunter stehende Vokal wird nasaliert)

a is spoken like Schwa in 'Palm e ', ai like 'ä' in 'H e rz', au like 'o' in ' o ffen'; e like 'ee' in 'S ee ', o like 'o' in ' O fen'.

- Non-retroflex consonants:

unaspiriert: p t k b d g c j q x f s z usw. aspiriert: ph th kh bh dh gh ch jh

h steht im Folgenden vereinfachend für [h], Visarga und Aspiration

j is pronounced as 'dsch' in 'jungle', c for 'tsch' in 'German', ṣ and ś (or simplified sh ) for the two sch-sounds, z for voiced 's' as in 'sun', x for the ach sound, q for uvular 'k'; y for 'j' as in 'year', v is pronounced as in 'vase'; Consonants written twice are long (for example cc for [c:] = 'ttsch').

- Retroflex consonants:

unaspiriert: ḍ ṭ ṛ ṇ aspiriert: ḍh ṭh ṛh

Morphology of nouns

Hindi knows the following types of nouns: nouns, adjectives and pronouns. Adjectives and possessive pronouns are placed in front of the noun to be determined and must be congruent with it. For the sequence of noun phrases, subject - indirect object - direct object generally applies. The rectus singular (masculine) is the citation form.

Hindi doesn't know a specific article. As an indefinite article, the unchangeable numeral ek 'one' can step in if necessary .

genus

In Hindi only masculine and feminine are differentiated, the neuter class no longer exists. The following applies to the distribution of the genera:

- Nouns that denote masculine persons are always masculine, those denoting feminine persons are always feminine.

- Some animal species have male and female forms, such as billā / billī 'tomcat / cat (female)', gadhā / gadhī 'donkey / donkey', bãdar / bãdarī “monkey”, hāthī / hathinī “elephant”, gāv / go or gāy 'cow', ghoṛā / ghoṛī 'horse'; with others there is only one general gender for the entire genus, such as ū̃ṭ (masculine) 'camel', makkhī (feminine) 'fly'.

- In the case of plants and objects, the gender is partly inherited from Urindo-European times.

number

- Hindi knows the numbers singular and plural .

- In the case rectus, the plural form of many nouns is indistinguishable from that of the respective singular (like ādmī 'man, men').

- Frequent plural endings are -e in masculines on -ā , -iyã in feminines on -ī , and -ẽ in feminines on consonant (see below).

Special plural formations:

- The ending -āt in some nouns of Arabic origin with the abbreviation of the preceding vowel shortened (like makān 'house'> makanāt 'houses').

- The very rare ending -ān (as in sāhib 'Lord, Master'> sahibān 'Lord, Master').

- In colloquial language it is also common to form the plural of person names with log “people” (like widyārthī 'student'> widhyārthī-log 'student').

Case and prepositions

Nouns have preserved three synthetic case forms : the " rectus " (English: direct case), the " obliquus " (English: oblique case) and the " vocative " (English: vocative [case]); only personal pronouns have their own possessive and dative forms. The rectus is also directly classified as nominative in linguistic literature, but has unusual properties for such a character.

The following applies to use:

- The rectus is the nominal form; it is used as a subject and an indefinite direct object - but not for subjects of transitive verbs in the perfective aspect: this is usually the ergative , which is an obliquus with the postposition ne .

- The obliquus must always be placed together with post positions and is used to form adverbs.

- The rare vocative is the case of direct address. The vocative can be found in the following tables under the respective obliquus form if both cases are identical.

The synthetic cases

The oblique plural ending is always -õ , the vocative plural ending is always -o . For the other cases, a distinction is made between TYPE 1 ( unmarked: no change in these forms) and TYPE 2 (marked) in masculine . TYPE 2 includes loanwords (mainly from Sanskrit, Persian, Arabic, English) and masculine words that do not end in -ā . In addition, there are Persian loanwords with special plural endings as TYPE 3; however, these nouns are usually treated by Hindi speakers like any other consonant noun.

- Masculine of TYPE 1:

Auf kurzes -a: mitra ‚Freund‘

Singular Plural Rektus: mitra mitra Obliquus: mitra mitrõ Vokativ: mitra mitro

Auf langes -ā: pitā ‚Vater‘

Singular Plural Rektus: pitā pitā Obliquus: pitā pitāõ Vokativ: pitā pitāo

Auf langes -ī: ādmī ‚Mann‘

Singular Plural Rektus: ādmī ādmī Obliquus: ādmī ādmiyõ Vokativ: ādmī ādmiyo

Auf kurzes -u: guru ‚Lehrmeister‘

Singular Plural Rektus: guru guru Obliquus: guru guruõ Vokativ: guru guruo

Auf langes -ū: cākū ‚Taschenmesser‘

Singular Plural Rektus: cākū cākū Obliquus: cākū cākuõ

Auf Konsonant: seb ‚Apfel‘

Singular Plural Rektus: seb seb Obliquus: seb sebõ

- Nouns of TYPE 2

Maskulina auf -ā: baccā ‚Kind‘

Singular Plural Rektus: baccā bacce Obliquus: bacce baccõ Vokativ: bacce bacco

Maskulina auf -̃ā: kũā ‚Brunnen‘

Singular Plural Rektus: kuā~ kuẽ Obliquus: kuẽ kuõ

Feminina auf -ī und einige andere haben -̃ā im Rectus Plural:

strī ‚Frau‘

Singular Plural Rektus: strī striyā~ Obliquus: strī striyõ

śakti ‚Kraft‘

Singular Plural Rektus: śakti śaktiyā~ Obliquus: śakti śaktiyõ

ciṛiyā ‚Vogel‘

Singular Plural Rektus: ciṛiyā ciṛiyā~ Obliquus: ciṛiyā ciṛiyõ

Feminina mit irgendeinem anderen Ausgang haben -ẽ im Rectus Plural:

1) Nicht kontrahiert:

kitāb ‚Buch‘

Singular Plural Rektus: kitāb kitābẽ Obliquus: kitāb kitābõ

bhāṣā ‚Sprache‘

Singular Plural Rektus: bhāṣā bhāṣāẽ Obliquus: bhāṣā bhāṣāõ

bahū ‚Schwiegertochter‘

Singular Plural Rektus: bahū bahuẽ Obliquus: bahū bahuõ Vokativ: bahū bahuo

2) kontrahiert:

aurat ‚Frau‘

Singular Plural Rektus: aurat aurtẽ Obliquus: aurat aurtõ Vokativ: aurat aurto

bahan/bahin ‚Schwester‘

Singular Plural Rektus: bahan bahnẽ Obliquus: bahan bahnõ Vokativ: bahan bahno

- Loan words from TYPE 3

kāγaz ‚Papier‘

Singular Plural Rektus: kāγaz kāγazāt Obliquus: kāγaz kāγazātõ

- Persian-Arabic loanwords that end in silent -h are treated like marked masculina (type 2): bacca (h) (Urdu spelling) ~ baccā (Hindi spelling).

- Some Persian-Arabic loanwords may have their original dual or plural markings: vālid 'father'> vālidain 'parents'.

- Many feminine Sanskrit loanwords end in -ā : bhāṣā 'language', āśā 'hope', icchā 'intention'.

The primary post positions

In addition to the synthetic cases, many new analytical formations have arisen through postpositions; Postpositions correspond to prepositions in German, but they are added afterwards. The preceding noun with any associated adjectives and genitive postpositions must always be placed in the oblique.

Rektus: gadhā ‚der Esel‘ Genitiv: gadhe kā ‚des Esels‘ Dativ: gadhe ko ‚dem Esel‘

Ergativ: gadhe ne ‚der Esel‘ Ablativ: gadhe se ‚vom Esel‘

‚in‘: ghar mẽ ‚in dem Haus‘ ‚auf‘: ghar par/pe ‚auf dem Haus‘ ‚bis zu‘: ghar tak ‚bis zum Haus‘

- The dative is the case of the indirect object and is used in some sentence constructions (like yah mujhe acchā lagtā ' I like that '). It also designates the direct object when it is determined (definite).

- The ergative is only used in the perfect tenses to identify the subject in transitive verbs.

- The ablative has many functions:

1) Herkunft (wie dillī se ‚aus Delhi‘; … se … tak ‚von … bis … ‘) 2) Anfangszeit (wie itvār se ‚seit Sonntag‘) 3) Kasus des Komparativs (siehe Abschnitt Komparation) 4) Darüber hinaus kann er instrumentale und adverbiale Funktionen haben und wird von einigen Verben als Patiens verlangt.

The word group of noun and the following genitive postposition behaves like an adjective, so that the postposition kā is inflected according to the form of the following word:

Maskulin Singular: ādmī kā kamrā ‚das Zimmer des Mannes‘ Maskulin Plural: ādmī ke kamre ‚die Zimmer des Mannes‘

Feminin Singular: ādmī kī gārī ‚das Auto des Mannes‘ (im Hindi ‚die Auto‘) Feminin Plural: ādmī kī gāriỹā ‚die Autos des Mannes‘

The compound post positions

The compound postpositions consist of the obliquus of the genitive postposition kā and the following adverb:

Örtlich … ke andar ‚(mitten) in‘ … ke bhītar ‚in … drin‘ … ke bīch mẽ ‚mitten in … drin‘ … ke bāhar ‚außerhalb von …‘

… ke pās ‚nahe bei …‘ … ke ās-pās ‚bei, in der Nähe von‘ … ke cārõ taraf/or ‚rings um … herum‘ … kī taraf ‚auf … zu‘

… (ke) nīce ‚unter‘ … ke ūpar ‚über … (drüber)‘

… ke āge ‚vor …, … voraus‘ … ke sām(a)ne ‚vor, gegenüber von …‘ … ke pīche ‚hinter‘

… ke bājū ‚neben‘ … ke bagal ‚neben‘ … ke sāmne ‚gegenüber von …‘ … ke kināre ‚auf der Seite von …‘

Zeitlich … ke bād ‚nach‘ … ke paihle * ‚vor‘ … (ke) daurāna ‚während‘

* dialektisch: pahile/pahale

Übertragen … ke liye ‚für‘ … ke khilāf ‚gegen‘

… ke dvārā ‚anhand, mittels‘ … ke mādhyam se ‚mithilfe von‘

… ke rūp mẽ ‚in Form von, als‘ … ke anusār ‚laut, gemäß‘ … ke bāre mẽ ‚über (Thema); bezüglich‘

… ke kārã (se) ‚wegen‘ … ke māre ‚wegen, aufgrund von; durch‘ … ke bavajūd ‚trotz‘

… ke sāth ‚(zusammen) mit‘ … ke bina ‚ohne, ausgenommen, außer‘ … ke yah̃ā ‚anstelle von‘ … ke badle mẽ ‚anstelle von, im Austausch für‘ … ke bajāy ‚anstatt‘ … ke alāvā ‚neben, abgesehen von, so gut wie‘ … ke sivāy ‚abgesehen/mit Ausnahme von‘

… ke shurū mẽ ‚am Anfang von …‘ … ke ãt mẽ ‚am Ende von …‘ … ke barābar/māfik ‚gleich/ähnlich …‘ … ke bīch mẽ ‚zwischen; unter (among)‘

prepositions

The Hindi knows the preposition binā "without", which can also be added afterwards ( ... ke bina ).

Adjectives

Adjectives (adjectives) can appear in front of a noun to be determined as an attribute, or they can also have a substantive function alone. In the attributive function and predicative (together with the copula honā ' to be'), a special, strongly restricted declination scheme applies to the declension as a noun, in which the vocative is always the same as the respective oblique.

Attributive declination

In Hindi, a distinction is made between declinable and undeclinable adjectives. A declinable adjective is adapted to the associated noun, an undeclinable adjective always remains unchanged. A number of declinable adjectives show nasalization in all terminations.

Declinable are most adjectives in -a border:

Maskulin: Rectus Singular -ā: choṭā kamrā ‚das kleine Zimmer‘

Sonst immer: -e: choṭe kamre ‚die kleinen Zimmer‘

choṭe kamre mẽ ‚im kleinen Zimmer‘

choṭe kamrõ mẽ ‚in den kleinen Zimmern‘

Feminin: immer -ī: choṭī gāṛī ‚das kleine Auto‘

choṭī gāṛiỹā ‚die kleinen Autos‘

choṭī gāṛī mẽ ‚im kleinen Auto‘

choṭī gāṛiyõ mẽ ‚in den kleinen Autos‘

- Examples of declinable adjectives: baṛā 'big', choṭā 'small', moṭā 'fat', acchā 'good', burā bad, 'bad', kālā 'black', ṭhaṇḍā 'cold'.

- Examples of undeclinable adjectives: xarāb 'bad', sāf 'clean', bhārī 'heavy (weight)', murdā 'dead', sundar 'beautiful', pāgal 'crazy', lāl 'red'.

The suffix sā / ~ se / ~ sī gives an adjective the shade '-lich' or 'fairly' (like nīlā 'blue'> nīlā - sā 'bluish'). It's ambiguous because it can both reinforce and tone down the meaning of an adjective.

Comparison (increase)

- The comparative is formed by aur / zyādā 'more' or came 'less'.

More-than-comparisons use the ablative postposition se : hāthī murge OBL se aur baṛā hai (meaning: 'the elephant is larger than the chicken ' ) 'the elephant is bigger than the chicken '.

In a comparison, the word for "more" can be omitted:

Gītā Gautam se (aur) lambī hai ‚Gita ist größer als Gautam‘ Gītā Gautam se kam lambī hai ‚Gita ist weniger groß als Gautam‘

This is not possible without a comparison object:

zyādā baṛā hāthī ‚der größere Elefant‘ hāthī zyādā baṛā hai ‚der Elefant ist größer‘

- The superlative is formed with sab 'all (s)': sab se āccha (analogously: 'in-comparison-to all large') 'the greatest'.

sab se mahãgā kamrā ‚das teuerste Zimmer‘ kamrā sab se mahãgā hai ‚das Zimmer ist das teuerste‘

- In registers with a strong influence from Sanskrit or Persian there are also suffixes from these languages:

Sanskrit Persisch Komparativ -tar Superlativ -tam -tarīn

Zwei dieser Bildungen sind unregelmäßig:

Positiv Komparativ Superlativ acchā behtar behtarīn ‚der gute/bessere/beste‘ kharāb badtar badtarīn ‚der schlechte/schlechtere/schlechteste‘

pronoun

Personal pronouns

Personal pronouns have their own accusative, differentiated from the nominative, which corresponds to the forms of the dative. The gender is not differentiated at all, but in the 3rd person the distance to the speaker. In personal pronouns, postpositions are regarded as bound morphemes in Hindi and as free particles in Urdu.

In northern India in particular, the first person plural ham 'we' is also used colloquially for the singular 'I'

There are the following pronouns for the 2nd person:

- tū 'you' (singular, intimate ) in small children, close friends, deities or in poetry; in all other cases it is condescending or even offensive.

- tum 'her' (plural, familiar ) is used for younger or lower placed people; it is also used for a single person when tū is inappropriate, so it can also be translated as "you" depending on the context.

- āp 'you' (plural, polite ) is used for older or higher-ranking people.

- tum and āp are already plural pronouns, but since they are also used to address a single person, they can expressly mark the plural again with the suffixes -log 'people' or -sab 'all': tum log / tum sab or āp log / āp sab (cf. the English you guys or y'all ). Nothing at all changes in their function in the sentence structure.

The demonstrative pronouns ( yah 'this here' / vah 'that there') are used as personal pronouns of the third person , and no distinction is made between female and male.

- The personal pronouns in the rectus:

Erste Person ich mãi wir ham

Zweite Person du tū ihr tum Sie āp – wird grammatikalisch als 3. Person Plural behandelt

Dritte Person: Hochsprache im Hindi Urdu und gesprochenes Hindi er/sie/es [hier] yah ye er/sie/es [dort] vah vo

sie [hier] (Plural) ye ye sie [dort] (Plural) ve vo

- The obliquus is also required for personal pronouns from the following post position:

1. Person Singular: mãi > mujh …

2. Person Singular: tū > tujh …

3. Person Singular hier: yah > is …

3. Person Singular dort: vah > us …

3. Person Plural hier: ye > in …

3. Person Plural dort: ve > un …

In ham , tum and āp , rectus and obliquus are identical.

- The dative usually also stands for the direct object:

1. Person 2. Person 3. Person Singular: mujhe tujhe ise / use Plural: hamẽ tumẽ inhẽ / unhẽ

Colloquially, the dative is also formed with the usual particle ko : mujh.ko (? Mere.ko) 'me / me', tujhko 'you / you', isko | usko 'him / him, you / she', hamko 'us', tūmko 'you', inko | unko 'them / they'.

- The ergative is formed irregularly in the 3rd person plural, in the 1st and 2nd person plural the respective rectus form is exceptionally in front of the post position:

1. Person 2. Person 3. Person Singular: mãi ne tū ne is ne / us ne Plural: ham ne tum ne inhõ ne / unhõ ne

possessive pronouns

- The personal pronouns mãi / ham and tū / tum have their own genitive forms that are used as possessive pronouns:

1. Person Singular: merā ‚mein‘ 1. Person Plural: hamārā ‚unser‘

2. Person Singular: terā ‚dein‘ 2. Person Plural: tumhārā ‚euer‘

They are adapted to the following noun like an adjective:

Maskulin Singular: merā kamrā ‚mein Zimmer‘ Maskulin Plural: mere kamre ‚meine Zimmer‘

Feminin Singular: merī gāṛī ‚mein Auto‘ (im Hindi ‚die Auto‘) Feminin Plural: merī gāṛiỹā ‚meine Autos‘

In the case of the other personal pronouns, the genitive is formed by the oblique form + the variable postposition kā , which is declined like merā and so on, just like with nouns :

yah (Singular) > is kā / is kī / is ke vah (Singular) > us kā / us kī / us ke

ye (Plural) > in kā / in kī / in ke ve (Plural) > un kā / un kī / un ke

āp > āp kā / āp kī / āp ke

relative pronoun

jo is the only relative pronoun. It is declined in a similar way to yah :

Singular Plural Rectus jo Obliquus jis... jin... Dativ jise... jinhẽ Genitiv jis kā jin kā Ergativ jis ne jinhõ ne

Interrogative pronouns

The interrogative pronoun kaun / kyā occurs in all cases and also in the plural. In the rectus a distinction is made between kaun 'who' (animate) and kyā 'was' (inanimate), in the other cases, which are formed in the same way as with the relative pronoun, there is no longer a gender difference:

Singular Plural Rectus kaun/kyā Obliquus kis... kin... Dativ kise... kinhẽ Genitiv kis kā kin kā Ergativ kis ne kinhõ ne

The adjective kaunā is 'which', which is declined like an adjective.

Indefinite pronouns

koī (Rectus), kisī (Obliquus) ‚jemand, irgendwer‘ (Singular) kuch ‚etwas‘ (Singular) kaī ‚irgendwelche, einige‘ (Plural)

- koī can also come before countable nouns in the singular with the meaning 'some / s', the neuter counterpart kuch also before uncountable nouns.

- koī as an adverb before a number word has the meaning 'about, approximately'. In this usage it does not get the oblique form kisī.

- kuch as an adverb can also define adjectives in more detail in the meaning of 'fairly'.

Many indefinite pronouns can also be used as negative pronouns if they are used together with a negative (in propositional sentences nahī̃ 'no, not', in command sentences also na, mat ):

kuch ‚etwas‘ kuch nah̃ī/na/mat ‚nichts‘ koī (bhī) ‚jemand, irgendwer‘ koī nah̃ī/na/mat ‚niemand‘ kah̃ī (bhī) ‚irgendwo‘ kah̃ī nah̃ī/na/mat ‚nirgendwo‘ kabhī bhī ‚irgendwann‘ kabhī nah̃ī/na/mat ‚nie‘

kyā at the beginning of a sentence has the function of marking the sentence as a decision question (yes / no). However, this can also only be done by mere intonation.

Further indefinite pronouns are:

koī bhī ‚irgendeine(r,s), irgendwer, wer auch immer‘ kuch aur ‚etwas anderes‘ sab kuch ‚alles‘ kaise bhī ‚irgendwie‘ kabhī na kabhī ‚irgendwann einmal‘

Derived pronouns

Interrogativ Relativ Demonstrativ hier / dort

Zeit kab ‚wann‘ jab ab / tab

Ort kah̃ā ‚wo(hin)‘ jah̃ā yah̃ā / vah̃ā

kidhar ‚wo(hin)‘ jidhar idhar / udhar

Quantität kitnā ‚wie viel‘ jitnā itnā / utnā

Qualität kaisā ‚wie beschaffen‘ jaisā aisā / vaisā

Art und Weise kaise ‚wie‘ jaise aise / vaise

Grund kyõ/kỹū ‚warum‘

kitnā / jitnā / itnā / utnā are declined like adjectives: kitnā (m) / kitnī (f) 'how much?' - kitne (m) / kitnī (f) 'how many?' and so on.

Also kaisā 'like (state), what kind of ' ( jaisā, aisā and vaisā of course also) is declined like an adjective and must therefore be adapted to the subject together with honā 'to be':

kaisā hai? ‚Wie geht's?‘ (zu einer männlichen Person) kaisī hai? ‚Wie geht's?‘ (zu einer weiblichen Person)

tum kaise ho? ‚Wie geht es euch/dir?‘ (zu einer männlichen Person) tum kaisī ho? ‚Wie geht es euch/dir?‘ (zu einer weiblichen Person)

āp kaise hãi? ‚Wie geht es Ihnen?‘ (zu einer männlichen Person) āp kaisī hãi? ‚Wie geht es Ihnen?‘ (zu einer weiblichen Person)

Verb morphology

overview

- Hindi knows 3 time levels - present (present tense), past (imperfect tense) and future (future tense) - and 3 aspects : the habitual aspect, the perfective aspect and the progressive form. The habitual aspect expresses what happens often or habitually, the progressive form corresponds roughly to the English continuous form on '-ing'.

- With transitive verbs in the perfect aspect, the subject is in the ergative .

- In the present tense a distinction is made between the following modes : indicative , subjunctive and imperative .

- Conjugation after persons without an auxiliary verb is only available for the verb 'sein', in the present subjunctive and in the definite future tense. The person endings for 'we', 'they' plural and 'you' are always identical. All other forms are formed using the simple stem or a participle and one or more auxiliary verbs, which have to be adapted to the subject according to number and gender.

- All forms listed below for yah 'he / it here' also apply to vah 'he / it there'; all the forms listed for ye 'they here' also apply to ve 'they there' and also to āp 'you'.

The strain

The stem of a verb is obtained by omitting the infinitive ending -nā . In addition to this stem, some verbs have other, irregular stem forms; this applies above all to the verbs denā ' to give', lenā 'to take' and jānā ' to go'.

The mere stem is used in front of the auxiliary verbs to form the progressive form and perfect, and also to form the tū imperative (see section imperative ).

Infinite forms

Infinite forms do not distinguish between person and mode.

- infinitive

The infinitive has the ending -nā (e.g. bolnā ' to speak'). The infinitive also serves as a gerund. It can therefore be placed in the obliquus like a noun, like bolne ke liye - literally: 'for speaking' - 'to speak'.

- Participles

The present participle has the ending -tā (like boltā , 'speaking'), the past participle the ending -ā (like. Bolā , 'having spoken').

- Verbal adverb

The verb adverb has the ending - (kar) (ke) (like bol / bolkar / bolke / bolkarke ). It has no direct German equivalent; Depending on the context, it could be translated as 'as / after ... has spoken' and so on.

Finite forms

Present indicative

The verb honā "to be" has got its personal inflection in the present indicative (for example: ṭhīk hũ 'I'm fine', yah kyā hai? 'What is that?'). (It originated from the Sanskrit root bhū- ' to be'; compare Pali: homi > Hindi hũ 'I am'.) It serves as a copula and also means' there is' (like hoṭel hai? 'Is there a hotel ? '):

Singular Plural mãi hũ ‚ich bin‘ ham hãi ‚wir sind‘ tū hai ‚du bist‘ tum ho ‚ihr seid‘ yah hai ‚er/es ist‘ ye hãi ‚sie sind‘

The other verbs are conjugated in the habitual present tense as follows: The present participle of any verb that has to be adapted to the subject is placed in front of the respective form of honā . For a male subject it has the endings -tā in the singular (like kartā , 'one making'), -te in the plural (like Karte 'several making'), for a female subject the ending is always -tī . This means, for example, mãi kartī hum ('I am doing') 'I do' - said by a woman.

Maskulines Subjekt Feminines Subjekt mãi kartā hũ ‚ich mache‘ mãi kartī hũ ‚ich mache‘ tū kartā hai ‚du machst‘ tū kartī hai ‚du machst‘ yah kartā hai ‚er macht‘ yah kartī hai ‚sie macht‘ ham karte hãi ‚wir machen‘ ham kartī hãi ‚wir machen‘ tum karte ho ‚ihr macht‘ tum kartī ho ‚ihr macht‘ ye karte hãi ‚sie machen‘ ye kartī hãi ‚sie machen‘

Present subjunctive

Like all verbs, the verb honā can form the subjunctive. However, there are still numerous subsidiary forms that are added in brackets:

Singular Plural mãi hũ (hoū) ham hõ (hoẽ, hovẽ, hõy) tū ho (hoe, hove, hoy) tum ho (hoo) yah ho (hoe, hove, hoy) ye hõ (hoẽ, hovẽ, hõy)

imperative

Hindi knows 3 imperatives , the use of which corresponds to that of the personal pronouns tū, tum and āp - the tum and āp imperatives can therefore be used for one or more people. The tū imperative corresponds to the mere stem of a verb, the other forms are formed by suffixes:

tū-Imperativ: bolnā ‚sprechen‘ → bol ‚sprich!‘ tum-Imperativ: bolnā ‚sprechen‘ → bolo ‚sprecht!‘ āp-Imperativ: bolnā ‚sprechen‘ → boliye ‚sprechen Sie!‘

Past tense

The habitual imperfect tense is formed by the present participle of the main verb + thā . Both adapt to the subject in number and gender; the feminine form thī has the irregular plural thī̃ :

Maskulines Subjekt Feminines Subjekt mãi kartā thā ‚ich machte‘ mãi kartī thī ‚ich machte‘ tū kartā thā ‚du machtest‘ tū kartī thī ‚du machtest‘ yah kartā thā ‚er machte‘ yah kartī thī ‚sie machte‘ ham karte the ‚wir machten‘ ham kartī thī̃ ‚wir machten‘ tum karte the ‚ihr machtet‘ tum kartī thī̃ ‚ihr machtet‘ ye karte the ‚sie machten‘ ye kartī thī̃ ‚sie machten‘

Future tense

The definite future tense is formed by adding the suffix gā / ge / gī to the forms of the subjunctive. (It is a contraction from * gaā < gayā, the past participle of jānā ' to go'). In Hindi it is regarded as a bound morpheme, in Urdu as a separate word.

Maskulines Subjekt Feminines Subjekt mãi karū~.gā ‚ich werde machen‘ mãi karū~.gī ‚ich werde machen‘ tū kare.gā ‚du wirst machen‘ tū kare.gī ‚du wirst machen‘ yah kare.gā ‚er wird machen‘ yah kare.gī ‚sie wird machen‘ ham karẽ.ge ‚wir werden machen‘ ham karẽ.gī ‚wir werden machen‘ tum karo.ge ‚ihr werdet machen‘ tum karo.gī ‚ihr werdet machen‘ ye karẽ.ge ‚sie werden machen‘ ye karẽ.gī ‚sie werden machen‘

The gradient forms

There are three imperfective tense forms for present, past tense and future tense. For their formation one takes the bare stem of the main verb (like kar- 'mach-'), behind which the auxiliary verb rahnā , 'to stay' is conjugated like any other verb in the present indicative, past tense and future tense:

- Progressive form in the present tense

Maskulines Subjekt Feminines Subjekt mãi kar rahā hũ ‚ich mache gerade‘ mãi kar rahī hũ ‚ich mache gerade‘ tū kar rahā hai ‚du machst gerade‘ tū kar rahī hai ‚du machst gerade‘ yah kar rahā hai ‚er macht gerade‘ yah kar rahī hai ‚sie macht gerade‘ ham kar rahe hãi ‚wir machen gerade‘ ham kar rahī hãi ‚wir machen gerade‘ tum kar rahe ho ‚ihr macht gerade‘ tum kar rahī ho ‚ihr macht gerade‘ ye kar rahe hãi ‚sie machen gerade‘ ye kar rahī hãi ‚sie machen gerade‘

- Progressive form in the past tense

Maskulines Subjekt Feminines Subjekt mãi kar rahā thā ‚ich machte gerade‘ mãi kar rahī thī ‚ich machte gerade‘ tū kar rahā thā ‚du machtest gerade‘ tū kar rahī thī ‚du machtest gerade‘ yah kar rahā thā ‚er machte gerade‘ yah kar rahī thī ‚sie machte gerade‘ ham kar rahe the ‚wir machten gerade‘ ham kar rahī thī~ ‚wir machten gerade‘ tum kar rahe the ‚ihr machtet gerade‘ tum kar rahī thī~ ‚ihr machtet gerade‘ ye kar rahe the ‚sie machten gerade‘ ye kar rahī thī~ ‚sie machten gerade‘

- Progressive form in the future tense

Maskulines Subjekt Feminines Subjekt mãi kartā rahū~.gā ‚ich werde gerade machen‘ mãi kartī rahū~.gī ‚ich werde gerade machen‘ tū kartā rahe.gā ‚du wirst gerade machen‘ tū kartī rahe.gī ‚du wirst gerade machen‘ yah kartā rahe.gā ‚er wird gerade machen‘ yah kartī rahe.gī ‚sie wird gerade machen‘ ham karte rahẽ.ge ‚wir werden gerade machen‘ ham kartī rahẽ.gī ‚wir werden gerade machen‘ tum karte raho.ge ‚ihr werdet gerade machen‘ tum kartī raho.gī ‚ihr werdet gerade machen‘ ye karte rahẽ.ge ‚sie werden gerade machen‘ ye kartī rahẽ.gī ‚sie werden gerade machen‘

The perfect forms

There are three perfect forms (perfect for the present tense, past perfect for the past tense, and future II for the future tense). For their formation one takes the bare stem of the main verb (like kar- 'mach-'), after which the auxiliary verb liyā or cukā is conjugated like any other verb in the present indicative, past tense and future tense. It should be noted that the "-ī" form of liyā has been shortened ( lī instead of liyī ):

- Perfect

Maskulines Subjekt Feminines Subjekt mãi kar liyā hũ ‚ich habe gemacht‘ mãi kar lī hũ ‚ich habe gemacht‘ tū kar liyā hai ‚du hast gemacht‘ tū kar lī hai ‚du hast gemacht‘ yah kar liyā hai ‚er hat gemacht‘ yah kar lī hai ‚sie hat gemacht‘ ham kar liye hãi ‚wir haben gemacht‘ ham kar lī hãi ‚wir haben gemacht‘ tum kar liye ho ‚ihr habt gemacht‘ tum kar lī ho ‚ihr habt gemacht‘ ye kar liye hãi ‚sie haben gemacht‘ ye kar lī hãi ‚sie haben gemacht‘

- past continuous

With the past perfect you have to use the post position 'ne'.

Maskulines Subjekt Feminines Subjekt mãine kar liyā thā ‚ich hatte gemacht‘ mãine kar lī thī ‚ich hatte gemacht‘ tūne kar liyā thā ‚du hattest gemacht‘ tūne kar lī thī ‚du hattest gemacht‘ isne kar liyā thā ‚er hatte gemacht‘ isne kar lī thī ‚sie hatte gemacht‘ hamne kar liya tha ‚wir hatten gemacht‘ hamne kar lī thī~ ‚wir hatten gemacht‘ tumne kar liya tha ‚ihr hattet gemacht‘ tumne kar lī thī~ ‚ihr hattet gemacht‘ unhõne kar liya tha ‚sie hatten gemacht‘ inhõne kar lī thī~ ‚sie hatten gemacht‘

- Future tense II

Maskulines Subjekt Feminines Subjekt mãi kartā liyū~.gā ‚ich werde gemacht haben‘ mãi kartī liyū~.gī ‚ich werde gemacht haben‘ tū kartā liye.gā ‚du wirst gemacht haben‘ tū kartī liye.gī ‚du wirst gemacht haben‘ yah kartā liye.gā ‚er wird gemacht haben‘ yah kartī liye.gī ‚sie wird gemacht haben‘ ham karte liyẽ.ge ‚wir werden gemacht haben‘ ham kartī liyẽ.gī ‚wir werden gemacht haben‘ tum karte liyo.ge ‚ihr werdet gemacht haben‘ tum kartī liyo.gī ‚ihr werdet gemacht haben‘ ye karte liyẽ.ge ‚sie werden gemacht haben‘ ye kartī liyẽ.gī ‚sie werden gemacht haben‘

The passive

The passive voice is formed from the past participle and the auxiliary jānā ' to go' (like likhnā ' to write'> likhā jānā ' to be written'). The agent has the post position se .

Intransitive and transitive verbs can be grammatically passivated to indicate physical or mental inability (usually in a negative sense). In addition, intransitive verbs often have a passive sense or express unintentional actions.

Numerals

Basic numbers

The numerals in Hindi are immutable. The numbers 11 to 99 are all irregular and must be learned individually. The similarities in the tens and units digits are sufficient to understand the number, but not for active control. The numbers 19, 29, 39, 49, 59, 69 and 79 (but not 89 and 99) are based on the form "1 of 20, 1 of 30" and so on.

0 śūnya 10 das 20 bīs 30 tīs 1 ek 11 gyārah 21 ikkīs 31 iktīs 2 do 12 bārah 22 bāīs 32 battīs 3 tīn 13 terah 23 teīs 33 tãitīs 4 cār 14 caudah 24 caubīs 34 cautīs 5 pā͂c 15 pãdrah 25 paccīs 35 pãitīs 6 chaḥ 16 solah 26 chabbīs 36 chattīs 7 sāt 17 sattrah 27 sattāīs 37 sãitīs 8 āṭh 18 aṭ(ṭ)hārah 28 aṭ(ṭ)hāīs 38 aŗtīs 9 nau 19 unnīs 29 untīs 39 untālīs

40 cālīs 50 pacās 60 sāṭh 70 sattar 41 iktālīs 51 ikyāvan 61 iksaṭh 71 ikahattar 42 bayālīs 52 bāvan 62 bāsaṭh 72 bahattar 43 tãitālīs 53 tirpan 63 tirsaṭh 73 tihattar 44 cauvālīs 54 cauvan 64 cãusaṭh 74 cauhattar 45 pãitālīs 55 pacpan 65 pãisaṭh 75 pacahattar 46 chiyālīs 56 chappan 66 chiyāsaṭh 76 chihattar 47 sãitālīs 57 sattāvan 67 saŗsaṭh 77 satahattar 48 aŗtālīs 58 aṭṭhāvan 68 aŗsaṭh 78 aţhahattar 49 uncās 59 unsaţh 69 unhattar 79 unāsī

80 assī 90 nabbe 100 (ek) sau 81 ikyāsī 91 ikyānave 101 ek sau ek 82 bayāsī 92 bānave 110 ek sau das 83 tirāsī 93 tirānave … 84 caurāsī 94 caurānave 1.000 (ek) hazār 85 pacāsī 95 pacānave 2.000 do hazār 86 chiyāsī 96 chiyānave … 87 satāsī 97 sattānave 100.000 ek lākh 88 aṭhāsī 98 aṭṭhānave 10 Mio. ek kroŗ 89 navāsī 99 ninyānave 100 Mio. ek arab

einmal ek bār zweimal do bār usw.

There are special terms for the numbers “one hundred thousand”, “ten million” and “one hundred million”. So instead of 20 million one says do kroŗ , for five hundred thousand or half a million pā͂c lākh . The numerals Lakh and Crore (= kroŗ) are also common in Indian English.

Fractions

½ ādhā 1¼ savā (ek) 1½ d˛eŗh 2¼ savā do 2½ (a)d˛hāī 3¼ savā tīn 3½ sāŗhe tīn 4¼ savā cār 4½ sāŗhe cār usw. usw.

paune… means '… minus a quarter', so paune do = 1¾, paune tīn = 2¾ and so on.

Adverbs

Hindi-Urdu has few inferred forms. Adverbs can be formed in the following ways:

- By putting nouns or adjectives in the obliquus: nīcā 'low'> nīce 'below', sīdhā 'straight'> sīdhe 'straight ahead', dhīrā 'slow'> dhīre 'slowly (in a slow way)', saverā 'morning'> savere 'in the morning', ye taraf 'this direction'> is taraf 'in this direction', kalkattā 'Calcutta'> kalkatte 'to Calcutta'.

- By post positions, for example se : zor 'strength'> zor se 'powerful, with strength', dhyān 'attention'> dhyān se 'attentive'.

- Postpositional phrases ": acchā good> acchī tarah se good, well, in a good way, xās especially> xās taur par in a special way.

- Verbs in the subjunctive: hãs- 'laugh'> hãs kar 'laughing, having laughed'.

- Sanskrit or Perso-Arabic suffixes in higher registers: skt. sambhava 'possible'> sambhava tah 'possibly'; arab. ittifāq 'chance'> ittifāq an 'chance'.

Sentence structure

Conjunctions

- Coordinating conjunctions

‚und‘ aur, ewam, tathā ‚oder‘ yā; athvā (formell) ‚aber‘ magar, kintu, lekin, par(antu) ‚und wenn nicht; sonst‘ varnā

- Subordinate conjunctions

‚dass‘ ki ‚weil‘ kyõki, kyũki ‚obwohl‘ agar(a)ce, yadyapi ‚wenn‘ (temporal) jab ‚wenn, falls‘ agar, yadi ‚wenn doch nur‘ kāsh ki ‚als ob, wie wenn‘ mānõ ‚ob … oder‘ chāhe ... chāhe/yā" ‚um … zu‘ (siehe Abschnitt Infinitiv)

For the relative pronouns starting with j- see section Relative Pronouns .

sentence position

In deviation from German:

- All verbs appear one after the other at the end of the sentence (like hoţel vahā ~ hai ('hotel there is'), 'there is a hotel'), also for questions and commands. A decision question without question particles can therefore only be recognized by the voice guidance (Hindi sounds relatively monotonous on the whole).

- The indirect always comes before the direct object.

- Mostly interrogative pronouns and negations ( nahī ~ / na / mat ) precede the verb in this order.

- kyā ('what?') to identify a decision question is at the beginning of the sentence; otherwise interrogative pronouns are not moved (like hoţel kahā ~ hai? ('hotel where is') 'where is there a hotel?').

- kripayā 'please' is at the beginning of the sentence; however, it is used far less than in German.

Language type

Hindi / Urdu is essentially an agglutinating SOV language with split ergativity, which has retained remnants of a once inflected character in relation to the two gender categories (masculine and feminine), different plural formations and irregular verb forms. A polysynthetic trait arises from the tendency to use attribute word groups instead of using the existing relative pronouns. Hindi knows both right and left branching phenomena, deviations from the normal word order often occur .

Example sentences

- Typical for Hindi is the genitive formation through the possessive article kā (masculine singular) / kī (feminine) / ke (masculine plural):

उस आदमी का बेटा विद्यार्थी है |

/ us ādmī kā beţā vidyārthī hai /

[ us ɑːdmiː kɑː beːʈɑː vidjɑːrt h iː hæː ]

(literally: this OBL man is OBL of son's student )

This man's son is a student.

- The indirect and sometimes also the direct object are formed with ko :

बच्चे को दूध दीजिए |

/ bacce ko dūdh dījiye /

[ bəc: eː koː duːd ɦ diːdʒieː ]

(literally: child OBL give the milk-you. )

Give the child milk!

- Preface words are added afterwards in Hindi, so they are called postpositions :

मकान में सात कमरे हैं |

/ makān mẽ sāt kamre hãi /

[ məkɑːn meː ~ sɑːt kəmreː hæː ~ ]

(literally: House OBL are in seven rooms. )

There are seven rooms in the house.

- The conjugation takes place in most forms using auxiliary verbs. For example, the progressive form is formed with the auxiliary rahnā "just being there". The auxiliary verb comes after the verb and can be conjugated in some tenses:

लड़के बग़ीचे में खेल रहे हैं |

/ laŗke baġīce mẽ khel rahe hãi /

[ ləɽkeː bəgiːtʃeː meː ~ k h eːl rəheː hæː ~ ]

(literally: boys garden OBL are in play. )

The boys are playing in the garden.

namaste (Allgemeine Begrüßung und Verabschiedung) āp kaise hãi? ‚Wie geht es Ihnen?‘ mãi ţhīk hũ ‚Mir geht es gut.‘ ... kahã hai? ‚Wo ist …?, Wo gibt es …?‘ sab kuch ţhīk hai! ‚Alles ist in Ordnung!‘

literature

- Narindar K. Aggarwal: A Bibliography of Studies on Hindi. Language and Linguistics. Indian Documentation Service, Gurgaon, Haryana, 1985.

- Erika Klemm: Dictionary Hindi - German. Around 18,000 headwords and phrases . 4th edition. Langenscheidt Verlag Enzyklopädie, 1995, ISBN 978-3-324-00397-1 .

- Margot Gatzlaff-Hälsing: Grammatical Guide of Hindi. Helmut Buske Verlag, Hamburg 2003, ISBN 978-3-87548-331-4 .

- Margot Gatzlaff-Hälsing: Dictionary German-Hindi. Helmut Buske Verlag, Hamburg 2000, ISBN 978-3-87548-247-8 .

- Margot Gatzlaff-Hälsing (Ed.): Concise Dictionary Hindi-German. Helmut Buske Verlag, Hamburg 2002, ISBN 3-87548-177-1 .

- Kadambari Sinha: Hindi Conversation Course. Helmut Buske Verlag, Hamburg 2007, ISBN 978-3-87548-488-5 .

- Rainer Krack: Gibberish - Hindi word for word. Reise Know-How Verlag, Bielefeld 2007, ISBN 978-3-89416-084-5 .

- RS McGregor: The Hindi-English Dictionary. Oxford University Press, Oxford 1997, ISBN 978-0-19-864339-5 .

- Rupert Snell: Teach Yourself Hindi. McGraw-Hill Companies, 2003, ISBN 978-0-07-141412-8 .

- Ines Fornell, Gautam Liu: Hindi bolo! Hempen Verlag Bremen 2012, ISBN 978-3-934106-06-2 . 2 volumes

- Hindi without effort Assimil GmbH 2010, ISBN 978-3896250230

- Hedwig Nosbers, Daniel Krasa: Entry Hindi for spontaneous people. Hueber Verlag 2009, ISBN 978-3190054374

- Hindi-German visual dictionary. Dorling Kindersley Verlag 2012, ISBN 978-3831091119

Individual evidence

- ↑ in detail on the case system of Hindi / Urdu: Miriam Butt: Theories of Case . Cambridge University Press, 2006

Web links

- "Hindi speaking tree" , a Hindi online course for beginners (English)