Shabbaba

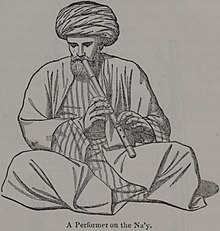

Shabbaba , asch-schabbāba , also shabbābah, şebbabe, schebāb, shbiba ( Arabic ), is a straight end flute or, more rarely, a notched flute played in Arabic folk music . The slender play tube made of wood, woody reed, metal or plastic typically has six finger holes and one thumb hole. The different variants of the shabbāba are mostly blown by young amateurs, traditionally by shepherds, for entertainment and occur in Jordan , Syria , Palestine , Egypt , Iraq and Bedouins in North Africa. The pitch range is smaller than that of the nāy played in the classical musical styles of the region , with nāy also being used as a generic term for the oriental open length flutes. Oriental flutes are also called māsūl .

The Yazidis worship the schebāb as a sacred musical instrument which together with the frame drum duff accompanied religious ceremonies.

Origin and Distribution

Apart from Paleolithic bone flutes , the oldest flute find is a Sumerian silver flute from Ur in Mesopotamia , which dates back to 2450 BC. Is dated. Flutes in ancient Egypt have been depicted since predynastic times (4th millennium BC). Of particular importance for the origin of the longitudinal flute is a palatial palette from Hierakonpolis that is kept in the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford . And shows a fox or jackal playing the flute. An obliquely held flute about one meter long, which is depicted on reliefs from the Old Kingdom (3rd millennium BC), was apparently part of the orchestra. Existing flutes from the Middle Kingdom onwards are between under 50 centimeters and about a meter long.

The most widespread collective term for longitudinal flutes open at both ends in the Near and Middle East is Arabic-Persian nāy ( nai, ney, "pipe"), correspondingly in Turkish ney . Name-related longitudinal flutes, which always consist of a long, slender tube, can be found in the south of Pakistan ( narh and nel ). An old Arabic name for a longitudinally blown flute in early Islamic times is qasāba ( al-qussāba ); this is where the current name gasba for a reed flute played in North Africa goes back. The gasba is a longitudinal flute common in the Maghreb and, exceptionally, a transverse flute in the Western Sahara . Other old flute names were and are as-suffāra and later al-ghaba and an-naqīb. Various small flutes were called pisha in Persian and dschuwāq in Berber . In Arabic folk music, small flutes are generally called sibs , whereby the main thing is the high notes of the instrument and sibs in Egypt in the orchestra can also mean small, high-pitched reed instruments . The name sibs stands for the purpose of a musical instrument and less for a specific shape. A naming based on the musical use is also used for other instruments; in the case of shabbāba and nāy , a shepherd's flute is essentially differentiated from a concert flute.

At the time of the Abbasids the flutes nāy, schabbāba, qasaba and saffāra were mentioned, furthermore the panpipe armūnīqī, the reed instruments mizmar ( zamr ), surnā (y) , zummara , zulāmī and mausūl as well as the brass instruments būq and nafīr . The Persian geographer Ibn Chordadhbeh (around 820 - around 912) traces the musical instruments back to their (from today's perspective mythical) origin, such as the drum ( tabl ) and the frame drum ( duff , Hebrew tof ) to the biblical figure Lamech and the flute ( saffāra ) on the Kurds . Later, according to Ibn Chordadhbeh, the Persians discovered the reed for making wind instruments (generally nāy ). An Egyptian miniature from the 14th century in the Kitāb Kaschf al-humūm (“Book of Significant Discoveries”) shows a flute player with the reed flute shabbāba. There it is said that the flute was called minghāra in ancient times and that corresponding flutes made of gold and silver were occasionally played at court.

In the 9th century the Arabs replaced the qasaba with the Persian nāy , only in the Maghreb it was still used. To this day, a 60 to 70 centimeter long flute with five to six holes is called qasaba . In Syria a beaked flute is called qasaba and in Yemen a longitudinal flute is derived from qasba .

Shabbāba is derived from the word schabbāb, "youth", "youth" and connects the idea of youthfulness with a musical instrument that was traditionally played mainly by young shepherds. This includes the idea that flute sounds come closest to the human voice and that the play of shabbāba expresses the exuberant feelings of young lovers.

The name of the old Spanish notched flute ajabeba , which is mentioned in the 14th century and probably came to al-Andalus together with the flute through the Arab conquest, comes from asch-shabbāba . An older spelling of ajabeba , first mentioned in 1294, is axabeba (or exabeba ). In a line of verse from the rhyming chronicle Poema de Alfonso Onceno , written in 1348, about King Alfonso XI. the flute is mentioned as "la exabeba morisca " to describe its Arabic origin .

Notched flutes were probably already around in the Egyptian New Kingdom (around 1550 - around 1070 BC) and most likely in the Ptolemaic period . Evidence of this is a bamboo flute without a finger hole found in Deir el-Medina , the upper end of which is shaped like a recorder mouthpiece. Arab travel writers of the 13th century mention beaked flutes ( yarā ) that they found in North Africa. The Andalusian scholar asch-Schakundi († 1231/32 in Córdoba ) reports that Seville was an important center for the manufacture of musical instruments and, among other things, beaked flutes ( yarā ) were delivered to western Sudan . There is also a Byzantine illumination from the 13th century with one of the earliest European images of a notch flute, on which seven finger holes can be seen. From the 17th century, notched flutes are known from Anatolia, where today's shepherd flutes occur as kaval and bilûr (for Kurds), in neighboring Armenia as blul and in eastern Georgia as salamuri . Flutes belonging to the pastoral culture are also popular in the Balkans (generally kaval, in Bulgaria also swirka ) and in Central Asia ( tulak ). Curt Sachs therefore suspects Asia as the region of origin of the flute, from where it could have reached the Iberian Peninsula via North Africa as an Arab cultural influence and at the same time via the Balkans to Western Europe.

Some longitudinal flutes are also played south of the Arab sphere of influence in Africa, such as the enderre kerbflute in Buganda , which is an instrument used by shepherd boys and court music. The nai (or semaa ) of the East African Swahili refers by name to a Turkish or Persian influence. In Madagascar , a flute whose name is related to the shabbāba is called sobaba .

Design and style of play

Georg Høst, who was Danish consul in the Moroccan port city of Essaouira from 1760 to 1768 , comments in his book Nachrichten von Maroccos und Fez (Copenhagen 1781) on a picture panel depicting several musical instruments of the Moors , including the small shabbāba flute :

- "Schabéba is a small flute, which gets its sound from topless without a plug, and in the way that a queer flute, but again so heavily, sounds almost like a queer whistle, but a little deeper and even sharper."

In the Middle East and Africa, longitudinal flutes that are open on both sides predominate, but notch flutes called shabbāba or māsūl (inner gap flutes) occur in North Africa and other areas, especially among Bedouins . They are played by nomad shepherds and occasionally by women as a soloist for their own entertainment. At weddings and other family celebrations, ensembles with flutes accompany a singing voice or a choir. The notch flutes, like the other longitudinally blown flutes, are usually made of wood or bamboo and are open at the bottom.

The name māsūl, which is limited to flutes, used to refer to wind instruments in general. The māsūl in the Middle East can be between 10 and 55 centimeters long and made of wood, cane, or baked clay. The 10 centimeter long māsūla flute with three finger holes made of clay or plastic is a children's toy. Māsūla , pipes of metal, apricot kernels or zoomorphic clay figurines, called by the Arabs also Safira or sūsāya and the Kurds fiqna .

Jordan

A typical open longitudinal flute shabbāba in the Middle East has an approximately 55 centimeter long cylindrical tube made of wood (apricot wood), reed (bamboo) or metal with six (five to seven) finger holes and a thumb hole on the underside. Due to the lack of reeds, which only thrive in some bodies of water, plastic is also used. The size spectrum of the shabbāba ranges from a short end-edge flute (without a beak) in Jordan with five finger holes without a thumb hole to a notched flute in Egypt with seven finger holes and a thumb hole. A short metal flute with a straight upper end in Jordan is 25 centimeters long, 1.5 centimeters in diameter and has five finger holes at a constant distance of two centimeters. Their range is two octaves (d 2 –d 4 ) with six tones each. The upper octave can be reached by blowing over, in practice the blowing technique only allows one octave. A short Jordanian shabbāba made of pipe is 35 centimeters long and has six finger holes and no thumb hole. The player takes the flute close to his lips, holds it down at a slight angle and blows, as with the nāy, towards the upper end, which is cut off at right angles and angled. A second method is to fix the flute end to an upper canine tooth. The disadvantage here is that part of the blown air gets back into the player's mouth.

In Jordan, the shabbāba and the tumbler drum tabla accompany the singer at family celebrations and other social occasions. The shabbāba plays a melody, which is then repeated by the singer in the same, higher or lower pitch. At family celebrations in Jordan and throughout the Middle East, the dabke dance is particularly popular, and is performed on happy occasions. A male musician stands in the middle of the circle of dancers and plays the melody on a shabbāba, otherwise on the double reed instruments midschwez or yarghul . The musical director sings the verses alternately with the choir of the dancers, interrupted by the interlude of the wind instrument. Despite its limited sound supply, the flute can be used for almost all Jordanian folk songs. Their simple melodies are mainly based on the Maqam Bayati; the shabbāba is tuned according to its scale .

With schabbāba is just like with the universal word NAY always a slim flute called. The nāy used in classical Arabic music has a clearer tone than the folk musical instrument shabbāba, which may have been its forerunner. The shabbāba belongs to the domain of men, while the classical nāy has been removed from popular tradition and is played by men and women.

Egypt

In Egypt , a distinction is made between the slender flutes, the ʿuffāta , a short, open length flute with a large diameter. For comparison, a medium-sized Egyptian ʿuffāta with a length of 42 centimeters has a diameter of 18 to 20 millimeters and a long nāy with a length of 72 centimeters is 11 to 13 millimeters. The six fingerholes of the ʿuffāta are arranged in two groups of three fingerholes each (according to the adjacent figure). In Egypt, Shabbāba and ʿuffāta have a common origin from the rural area and both are played in small ensembles in the villages to accompany songs and with other flutes of different lengths. An Egyptian reed flute ( māsūl ) from the 19th century is 26 centimeters long and 2.3 centimeters in diameter.

In Egypt, a typical flute ensemble, well-known in folk music, consists of two long flutes ( ʿuffāta ), a flute half as long ( sibs ) and two double-headed cylinder drums ( tabl baladī ). As regional variations, one or two flutes (here salāmīya ) with a double clarinet ( arghūl ) or flutes and the frame drum tār play together in connection with clapping of hands to accompany the singing. The one to three flutes of the accompanying ensembles in the Nile Valley always include a small sibs. Other drums in these ensembles are the riq frame drum and the darbuka goblet drum . Flutes can also be played in the ritual ensemble of the Egyptian zār cult, in which the lyre tanbura is otherwise of central importance. The names of the flutes are generally given differently. In addition to the names mentioned, the unspecific designation nāy is also used. Regionally, some Egyptians refer to either all longitudinal flutes without thumb holes or only high-pitched flutes as suffāra and the kerbflutes as shabbāba . Occasionally, flutes, one octave higher than the Suffara or Salamiya sound kawal called. Salāmīya , like ʿuffāta, can also refer to flutes whose finger holes are divided into two groups with a greater distance between them. In contrast, the flutes called ʿuqla and zafāfa have evenly arranged finger holes. In Egypt, flutes made of reed without finger holes are known, which were originally used in rituals and are now used as children's toys.

Maghreb

The shape and style of playing the open length flute type shabbāba corresponds to the gasba (high Arabic qasāba ) in the Maghreb . The combination of gasba and the frame drum bendir , along with the combination of the cone oboe ghaita (or zurna ) and the cylinder drum t'bol and the box- neck lute gimbri with other instruments, is one of the three traditional ensembles with which Berbers accompany their songs. The interplay of the notched flute yarā with the frame drum duff or the end-edge flute nāy with the frame drum mizhar is already described in a verse by the pre-Islamic Arab poet al-Aʿschā Maimūn (around 570 - around 629).

Religious music of the Yazidis

To worship the Yazidis in certain occasion, the musical presentation is part of a Qawl (see. Qawwali ) poem called, which is a part of the traditional religious knowledge. The qawl are performed by professional reciters ( qawwāl, qewwal ) who pass on their tradition orally within the family. The hymns written in Kurmanji consist of an average of 20 to 60 verses, which usually have an ending rhyme. The longest poem contains 117 verses. A qawwāl has mastered a certain number of these poems and the associated melody ( kubrí ). In the qawl , myths about the development of the community, cosmogony , religious and ideological themes are handed down. The performance of the hymns is accompanied by the sacred flute shebaab and the frame drum duff.

Accordingly, the reed flute ney is part of the ritual of the Sufi Mevlevi order in Turkey. The sacred meaning of the reed flute has a tradition in Anatolia that goes back to antiquity, when the flute player was given the task of invoking the gods with a spoken lecture and his flute in an epiclesis . The veneration of the two musical instruments by the Yazidis also obviously goes back to pre-Islamic times.

The community of the Yazidis is divided into three main religious groups: lay people (Murīd) and the religious leadership classes Sheikh and Pīr. The qawwāls form a separate hereditary caste from the three, which is responsible for playing the sacred instruments schebāb and duff . They come from the two small towns of Baschiqa and Bahzani in northern Iraq, where the Yazidi inhabitants do not speak Kurmanji, but an Arabic dialect. Part of the religious training of the Qawwāls, which not every member of this group has completed, is to know a certain number of religious texts by heart, the training of the strongest possible voice and the playing of the two musical instruments. This makes the qawwāls the keepers of the religious tradition that they pass on when they roam the land and perform ceremonies. In the 1960s, education began to be institutionalized in schools.

Occasions when Qawwāls recite the religious texts for the Yazidi general population are the New Year festival Çarşema Sor and the religious festival Tawusgerran ( tāwūs-gērrān, "circulation of the peacock"), in the case of the Yazidis there are metal peacock figures ( sanjaq, sancak, religious) Insignia ) of the revered Melek Taus in the villages. Tawusgerran is the main religious festival in the Yazidi villages. The seven existing sanjaq are the essential cult objects in Yezidism. From the sanjaq shown at the Tawusgerran, the believers promise divine assistance. At the same time, the event offers a necessary meeting place for the scattered villagers. During the exhibition of a sanjaq , the top qawwāl first sings a hymn, then the flute and frame drum accompany other qawwāl's hymns. Meanwhile, the believers approach the peacock figure, kiss it and donate a sum of money. Traditionally, non-Yazidis are not allowed to take part in the festival. Boundaries, political problems in the region and finally the security situation in Iraq have ensured in the course of the 20th century that the Iraqi qawwāls can no longer travel to the neighboring countries and thus the Tawusgerran can hardly be carried out.

literature

- Ali Salem Hussein Al-Shurman: Al-Shabbabah. In: IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) , Vol. 19, No. 8, Ver. VII, August 2014, pp. 12-21

- Shabbāba . In: Laurence Libin (Ed.): The Grove Dictionary of Musical Instruments . Vol. 4, Oxford University Press, Oxford / New York 2014, pp. 481f

Web links

- ده ف وشباب Daf ü schebab. Youtube video ( duff and shebaab in the main Yazidi shrine in Lalisch , Northern Iraq)

- Yezidi, Lalish, Kurdistan, Iraq. Youtube video (festival in the Lalisch sanctuary)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Mohammad T. Al-Ghawanmeh, Rami N. Haddad, Fadi M. Al-Ghawanmeh: Appliance of Music Information Retrieval System for Arabian Woodwinds in E-Learning and Music Education. In: Proceedings of the International Computer Music Conference (ICMC 2009), Montreal, Canada, 16. – 21. August 2009

- ↑ Two dog range . Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

- ^ Marcelle Duchesne-Guillemin: Music in Ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt . In: World Archeology , Vol. 12, No. 3 (Archeology and Musical Instruments) February 1981, pp. 287-297, here p. 291

- ^ Hans Hickmann: The music of the Arab-Islamic area. In: Bertold Spuler (Hrsg.): Handbuch der Orientalistik. 1. Dept. The Near and Middle East. Supplementary Volume IV. Oriental Music. EJ Brill, Leiden / Cologne 1970, p. 71f

- ↑ Hans Hickmann, 1970, p. 59; Jürgen Elsner: Remarks on the Big Arġūl. In: Yearbook of the International Folk Music Council , Vol. 1, 1969, pp. 234-239, here p. 236

- ^ Hans Hickmann: The Antique Cross-Flute . In: Acta Musicologica, Vol. 24, Issue 3/4, July - December 1952, pp. 108–112, here p. 111

- ^ Henry George Farmer : A History of Arabian Music to the XIIIth Century. Luzac & Co., London 1929, p. 210

- ^ Henry George Farmer: Music History in Pictures . Volume 3: Music of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Delivery 2: Islam. Deutscher Verlag für Musik, Leipzig 1966, pp. 24, 104

- ↑ Qaṣaba. In: Laurence Libin (Ed.): The Grove Dictionary of Musical Instruments. Vol. 4, Oxford University Press, Oxford / New York 2014, p. 190

- ^ WH Worrell: Notes on the Arabic Names of Certain Musical Instruments. In: Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 68, No. 1, January-March 1948, pp. 66-68, here p. 67

- ^ Sibyl Marcuse : Musical Instruments. A Comprehensive Dictionary. Country Life Limited, London 1964, p. 7 ( Ajabeba ), p. 27 ( Axabeba )

- ^ Walter Mettmann: To the lexicon of the older Spanish. In: Romanische Forschungen, Volume 74, Issue 1/2, 1962, pp. 119–122, here p. 120

- ↑ Hans Hickmann: Unknown Egyptian sound tools (Aërophone) (conclusion). In: Die Musikforschung, 8th year, issue 4, 1955, pp. 398–403, here p. 400

- ^ Henry George Farmer: Early References to Music in the Western Sūdān. In: Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, No. 4, October 1939, pp. 569-579, here p. 570

- ^ Curt Sachs : Handbook of musical instrumentation. (Leipzig 1930) Reprint: Georg Olms, Hildesheim 1967, p. 302

- ^ Gerhard Kubik : Music history in pictures. Volume 1: Ethnic Music. Delivery 10: East Africa. Deutscher Verlag für Musik, Leipzig 1982, p. 23

- ↑ Shabbāba. In: Sibyl Marcuse: Musical Instruments. A Comprehensive Dictionary. Country Life Limited, London 1964, p. 470

- ^ Georg Höst: News from Maroccos and Fes, collected in the country itself, in the years 1760 to 1781. Translated from the Danish. Copenhagen 1781, pp. 261f; quoted from: Paul Collaer, Jürgen Elsner: Music history in pictures. Volume 1: Ethnic Music. Delivery 8: North Africa . Deutscher Verlag für Musik, Leipzig 1983, p. 168

- ↑ Timkehet Teffera: Aerophone in the instruments of the peoples of East Africa. (Habilitation thesis) Trafo Wissenschaftsverlag, Berlin 2009, p. 228

- ↑ Scheherazade Qassim Hassan: Māṣūl and Māṣūla . In: Laurence Libin (Ed.): The Grove Dictionary of Musical Instruments. Vol. 3, Oxford University Press, Oxford / New York 2014, p. 412

- ↑ Shabbāba. In: Laurence Libin (Ed.): The Grove Dictionary of Musical Instruments, 2014, p. 482

- ↑ Ali Salem Hussein Al-Shurman, 2014, pp. 15-17

- ↑ Mohammad T. Al-Ghawanmeh, Rami N. Haddad, Fadi M. Al-Ghawanmeh: Appliance of Music Information Retrieval System for Arabian Woodwinds in E-Learning and Music Education.

- ↑ Ali Salem Hussein Al-Shurman, 2014, p. 19

- ^ Maqam Bayati Family. Maqam World

- ↑ Illustration of an Egyptian flute with six finger holes in two groups. In: Edward William Lane: An Account of the Manners and Customs of the Modern Egyptians. London 1936

- ^ Hans Hickmann: The Egyptian 'Uffāṭah Flute . In: The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, No. 3/4, October 1952, pp. 103f

- ↑ Duct flute (masul?) Museum of Fine Arts Boston (illustration)

- ^ Artur Simon : Studies on Egyptian Folk Music. (Dissertation) Volume 1. Verlag der Musikalienhandlung Karl Dieter Wagner, Hamburg 1972, p. 16

- ^ Paul Collaer, Jürgen Elsner: Music history in pictures. Volume 1: Ethnic Music. Delivery 8: North Africa. Deutscher Verlag für Musik, Leipzig 1983, pp. 19, 24, 32, 34, 70

- ↑ Hans Hickmann: Unknown Egyptian sound tools (Aërophone) (conclusion). In: Die Musikforschung, 8th year, issue 4, 1955, pp. 398–403, here p. 401

- ^ Henry George Farmer: Music History in Pictures. Volume 3: Music of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Delivery 2: Islam. Deutscher Verlag für Musik, Leipzig 1966, p. 26

- ↑ Philip G. Kreyenbroek: Qawl. In: Encyclopædia Iranica .

- ↑ Annemarie Schimmel : The signs of God. The religious world of Islam. CH Beck, Munich 1995, p. 181

- ↑ Christine Allison: Yazidis. i. General. In: Encyclopædia Iranica. Qawwāl generally means a professional poet singer in Arabic.

- ^ Sebastian Maisel: Social Change Amidst Terror and Discrimination: Yezidis in the New Iraq. In: The Middle East Institute Policy Brief, No. 18, August 2008, pp. 7f

- ^ Christine Allison: “Unbelievable Slowness of Mind”: Yezidi Studies, from Nineteenth to Twenty-First Century. In: The Journal of Kurdish Studies, Vol. 6, 2008, pp. 1–23, here p. 14

- ^ Peter Nicolaus: The Lost Sanjaq . In: Iran & the Caucasus, Vol. 12, No. 2, 2008, pp. 217-251, here p. 221

- ↑ Philip. G. Kreyenbroek: Yezidism in Europe: Different Generations Speak about their Religion. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2009, p. 22f