Bucharest

|

Bucureşti Bucharest |

||||

|

||||

| Basic data | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| State : |

|

|||

| Historical region : | Great Wallachia | |||

| Circle : | Bucureşti | |||

| Coordinates : | 44 ° 26 ' N , 26 ° 6' E | |||

| Time zone : | EET ( UTC +2) | |||

| Area : | 228 km² | |||

| Residents : | 1,821,000 (2018) | |||

| Agglomeration : | 2,200,000 (2018) | |||

| Population density : | 7,987 inhabitants per km² | |||

| Postal code : | 010011-062397 | |||

| Telephone code : | (+40) 02 1 | |||

| License plate : | B. | |||

| Structure and administration (as of 2016) | ||||

| Community type : | Municipality | |||

| Structure : | 6 sectors | |||

| Mayor : | Gabriela Firea ( PSD ) | |||

| Website : | ||||

Bucharest ( Romanian : București [ bukuˈreʃtʲ ]; ) is the capital of Romania . With a little more than 1.8 million inhabitants and an urban agglomeration of 2.2 million inhabitants, it is the seventh largest city in the European Union .

After Bucharest had finally replaced Târgovişte as the state capital in 1659 , it became the political, economic and cultural center of Wallachia and later of Romania. The city has several universities , various other colleges and numerous theaters , museums and other cultural institutions.

The cosmopolitan high culture and the dominant French influence of the neo-baroque architecture of the city earned it the nickname Micul Paris ("Little Paris", also "Paris of the East"). During the tenure of the Romanian dictator Nicolae Ceaușescu , extensive historical districts were destroyed in order to make way for the monumental confectioner style of the head of state.

geography

Bucharest is located 55 to 96.3 meters above sea level in the center of the Wallachian Plain, 68 kilometers north of the Danube and 280 kilometers west of the Black Sea . The Dâmbovița flows through the city; its tributary, the Colentina , forms a chain of nine natural lakes to the north of the city.

geology

The city is located south of the Eastern Carpathian Arc and the Vrancea Zone between the Black Sea microplate and the Moesian plate in one of the most earthquake- affected areas in Europe. Strong earthquakes pose a significant threat to the Romanian capital. Over the past 60 years, four strong earthquakes (November 10, 1940, March 4, 1977 , August 30, 1986 and May 30, 1990) occurred below the so-called Vrancea region 130 kilometers from Bucharest. Because of the very inhomogeneous subsurface structure, there is a fifty percent statistical probability of an earthquake of magnitude M = 7.6 within 50 years. The seismic risk in Bucharest is determined by the earthquake activity in the Vrancea zone in the eastern Carpathian arc, which is related to postorogenetic events in a Miocene subduction zone . The medium-depth earthquakes in this narrowly defined region are the cause of the sometimes catastrophic earthquake damage in Bucharest.

climate

The climate is temperate continental . In the months of June, July and August the average temperature is over 20 ° C. Winter temperatures are often below 0 ° C. However, they rarely drop below −10 ° C. In January 1888 the lowest temperature was measured at −30 ° C and the highest temperature was measured in Bucharest on August 20, 1945 at 41.1 ° C. Notorious in winter is the Crivăț, a cold continental wind that blows from the northeast and brings permafrost and blizzards with it.

|

Average monthly temperatures and rainfall for Bucharest

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The total annual precipitation in Bucharest is 579 millimeters. The annual mean temperature is 11.1 ° C. The coldest month of the year is January, with an average low temperature of −5 ° C. The hottest months are July and August, with an average high of 27 ° C.

City structure

Bucharest has a special administrative status in Romania and is not subject to any district administration. The city was divided into six administrative sectors (sectoare) in 1968 , the boundaries of which were redefined in the summer of 1979. The sectors and their districts are:

| Sectors | Districts |

|---|---|

| Sector 1 | Aviatorilor, Aviației, Băneasa, Bucureștii Noi, Dămăroaia, Domenii, Dorobanți, Floreasca, Gara de Nord, Grivița, Pajura, Pipera, Primăverii, Victoriei |

| Sector 2 | Colentina, Iancului, Pantelimon, Tei |

| Sector 3 | Balta Albă, Centru Civic, Dudeşti, Titan, Vitan |

| Sector 4 | Berceni, Olteniței, Timpuri Noi, Văcăreşti |

| Sector 5 | Cotroceni, Ferentari , Rahova |

| Sector 6 | Crângași, Drumul Taberei, Giulești, Militari |

Each of these sectors has a council with 27 seats, a town hall and a mayor. An expansion of the urban area is planned. Those responsible are planning to incorporate the small town of Otopeni north of Bucharest .

history

According to legend, Bucharest was founded by a shepherd named Bucur. Bucurie means happy joy in Romanian, and Bucur is a common family name. In the etymological sense, Bucureşti means : You are happy. Another story tells of the Getic king Dromichaites who built the city of joy .

City foundation, residence of the princes of Wallachia

Bucharest is mentioned for the first time in a document dated September 20, 1459. The certificate was issued by the voivode and general Vlad Țepeş , nicknamed Drăculea .

In the second half of the 15th century, Bucharest developed into the Curtea (princely seat) of Wallachia , where as early as 1400 there was a craftsmen's settlement with a blacksmith's, pottery and tannery . On October 14, 1465, Prince Radu the Beautiful named Bucharest in a document as the seat of a prince. The city achieved its central urban importance as a princely center of power and trade, which was located in a conurbation of settlements. Between 1459 and 1625 41 settlements appear in the area of today's Bucharest alone.

Subsequently, Bucharest was alternately with Tîrgovişte capital of Wallachia . The main market was built around Lipscani Street.

Ottoman era

The Ottoman Empire expanded from Asia Minor to what is now Romania in the 14th century . As early as 1394, the first Ottoman army advanced across the Danube. After that, the Principality of Wallachia was first subject to tribute.

Under this Ottoman suzerainty , Bucharest, which was still village-like, experienced an upswing due to the presence of the court and the return of foreign traders. The population increased and an urban structure developed, which was expressed by a large number of new buildings. In 1545 Prince Mircea Ciobanul built the first city wall in the form of a palisade wall . A large part of the agriculturally used land surrounding the city has now also been marked with boundary stones as “the land of the city citizens” (moșia orășenilor) .

Thirty years later, in 1574 and 1575, and in 1594, the population of Bucharest rose against the growing tributes of the Sublime Porte . She also took part in the Mihai Viteazul (Michael the Brave) battles against the Ottoman army , which were ultimately unsuccessful. After this fell from the Ottomans, Grand Vizier Koca Sinan Pasha conquered the city in August 1595 after the battle of Călugăreni . A city fire broke out. In the autumn of the same year another battle broke out near Bucharest, in which the Turks withdrew and destroyed part of the city in the process. For this reason, the prince's seat was then moved to Târgovişte until 1626. Shortly after taking power, Prince Alexandru Coconul moved the residence back to Bucharest on November 10, 1626 .

After Prince Matei Basarab was the last of the predominant Wallachian family to take the throne in 1632, he built numerous buildings in Bucharest. Because of his tense relationship with the Ottomans, the prince moved to Târgovişte around 1640. Meanwhile, the princely seat remained in Bucharest. Basarab's successor, Prince Constantin Șerban , moved to Bucharest again after taking office in May 1654. The following year, the Dorobantzen and infantrymen revolted against the boyars at the headquarters of today's National Bank . On the occasion of the riots, Prince Șerban had the royal court and the city set on fire when he withdrew to Târgovişte and moved the princely seat.

In 1659 the residence was relocated again. After his enthronement, Prince Gheorghe Ghica moved the princely seat back to Bucharest on December 20, 1659. In the same year, under pressure from the Ottoman Empire, the city became the sole residence of the voivodes . From that year on, Bucharest remained the final capital of Wallachia. In 1668, the prince was followed by the religious leadership of Orthodoxy to Bucharest. During this period, the city's population grew to around 60,000, which is now spread over 21 districts (so-called mahalale ). At that time there were about 100 churches. During the reigns of Șerban I. Cantacuzino and Constantin Brâncoveanu , Bucharest flourished for a long time. The first hospitals, printing works, educational institutions, numerous churches, Mogoșoaia Castle and the grand and arterial road Podul Mogoșoaia were built on the orders of the princes. The power-hungry Prince Brâncoveanu also abolished the mayor and city council and reserved the right to govern.

In the Phanariot period (1716–1821) the burden of the population through higher taxes and tributes, but also through nepotism and corruption, increased so much that this phase is considered the epitome of exploitation, corruption and mismanagement in Romania. In 1753, due to the unbearable tax burden on the intervention of the Bucharest people, Prince Matei Ghica was ousted by the High Porte . Twelve years later, Ștefan Racoviță met the same fate during the revolt of the guilds . The prince defeated the rebels, but was deposed by the Sublime Porte because of the reprisals he had imposed.

The members of the royal family Ypsilantis, on the other hand, made visible contributions to Bucharest. During the reign of Alexander Ypsilanti , many improvements to the city took place and the first aqueduct was built (1779). Because of the frequent flooding of the Dâmbovița, the prince also had a diversion canal built. At the same time, the first industrial development began in the city through factories . In 1764 a wax factory was established, one for clothes in 1766, and one for paper in 1767. In 1811, 2,981 people were already working in the trade and craft sector.

This development was briefly interrupted during the Russo-Austrian Turkish War, when Prince Nicolae Mavrogheni fled the city on October 26, 1789, accompanied by an army of around a thousand men. The city was captured by the Austrians two weeks later on November 10, 1789 and only released again in the peace treaty of August 4, 1791. Subsequently, various natural disasters, a conflagration and epidemics hit the city between 1793 and 1812.

Transitional period (1807 to 1861)

In 1807, during the Russo-Turkish War , Bucharest came under the command of the commander of the Russian troops. The first peace of Bucharest on May 28, 1812 ended the war between Russia and the Ottoman Empire, which had been ongoing since 1806 .

The increased exploitation of the Wallachian masses and the spread of revolutionary ideas of the French bourgeoisie as well as the hetary influenced anti-Ottoman public opinion at the turn of the century. During the following uprising , the Wallachian leader Tudor Vladimirescu stayed in Bucharest from March to May 1821. This led to violent retaliation by the Turkish troops who subsequently occupied Bucharest. These reprisals only ended with the withdrawal of the army in September 1822 and Prince Grigore IV Ghica's accession to the throne .

After the Treaty of Adrianople in 1829, Bucharest came under Russian protection. From that year until 1834 General Pavel Kisselev administered the city. During his tenure, the decree of the organic regulations (Règlement organique) was introduced and a committee was set up to beautify the city. The city limits were redefined. Further urban development measures, such as the creation of promenades and marketplaces, were implemented.

A major fire in the commercial part of the city destroyed around 2,000 houses on March 23, 1847. After the fire, a planned reconstruction followed. The following year Bucharest was the center of the Wallachian Revolution . The revolution that began on June 11, 1848, was bloodily suppressed three months later on the evening of September 13 on Mount Spirei. A memorial commemorates the event at this point. Between 1853 and 1856, Bucharest was successively occupied by Russian, Turkish and Austrian troops.

Bucharest became the first Romanian city to introduce kerosene lamps into street lighting in May 1857 . In the same year, by decree of the Sultan in Bucharest, the “Diwan Ad Hoc Assembly” met. The assembly passed a resolution on October 9, 1857, which, among other things, provided for the unification of Romania into one state.

Capital of Romania, industrialization until the First World War

Alexandru Ioan Cuza proclaimed the formation of the Principality of Romania from the Danube Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia on December 24, 1861 . A year later, the two principalities were also formally united with Bucharest as the capital. However, the founder of the state, Alexandru Ioan Cuza, came under fire and therefore had to abdicate in 1866. In the same year, a provisional government appointed Karl Eitel Friedrich von Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen as prince on recommendation . After his official election as prince, he moved into Bucharest as Carol I on May 10, 1866.

In 1869 the capital got its first railway line. It connected Bucharest with Giurgiu . Two years later the first tram line (at that time still a horse tram) was opened from the Nordbahnhof via Pia Pa St. Georg to Piața Obor. After four years of construction, the North Railway Station opened in 1872 , as did rail traffic between Bucharest and Ploieşti .

After the Berlin Congress in 1878, Romania was recognized as independent. As a result, on March 26, 1881, the Principality proclaimed itself to be the Kingdom of Romania. Bucharest was transformed into an imperial city. The young kingdom oriented itself towards the west, especially towards France. During the subsequent modernization, Prussia was a supplier of ideas and technology.

Towards the end of the 19th century, Bucharest gradually developed into an industrial center, especially in light industry. Five major banking institutions - including the National Bank , the Bank of Romania, the Agricultural Bank and, since 1898, the Discount Bank - made Bucharest the national financial center. Electric light was introduced on Calea Victoriei in 1890. During this time, the new traffic artery from Obor to Cotroceni was opened. In 1896 the line service of the first electric tram followed on the same route.

In 1886 the Treaty of Bucharest ended the war between Serbia and Bulgaria. The Second Balkan War was also ended in the city in 1913 with the signing of the Bucharest Peace Treaty between Serbia, Greece and Romania on the one hand and Bulgaria on the other.

From the First to the Second World War

During the First World War , Bucharest was occupied by German troops from December 6, 1916 as a result of the Battle of the Argesch until the peace treaty of May 7, 1918 . With the flight of the king and the government, Iași became the provisional capital of Romania during this period. The city's importance as the capital of " Greater Romania " only increased again after the First World War .

From 1918 to the beginning of the Second World War , the urban area increased by 5600 to 7800 hectares. The number of the population increased from 380,000 to 870,000 inhabitants in the same period. International interest aroused a strike by oil workers and railroad workers who had stopped working because of the deteriorating living conditions. On February 16, 1933, the strike at the Grivița works was brutally suppressed.

With the construction of the axis Piața Victoriei and Piața Sf. Gheorghe between 1936 and 1940, based on the Parisian model of the Boulevard Henri Martin and the Brussels design of the Boulevard Louise , the city was nicknamed "Paris of the East". In the 1940s, building activity continued in a western style, but this time in a modern, international style , which was characterized by names such as Le Corbusier or terms such as "Form and Function".

Bucharest in World War II

During the Second World War, Romania joined the three-power pact between the German Empire , the Japanese Empire and the Kingdom of Italy on November 23, 1940, after initially being neutral . This was the direct result of the formation of the government of a "national legionary state" on September 4, 1940 by the Iron Guard and General Ion Antonescu and led to the abdication of Carol II in favor of his 19-year-old son Mihai. One month later, on October 8, German troops crossed the Romanian border. Shortly afterwards, the Wehrmacht entered Bucharest. In January 1941, a coup attempt by the far-right legionaries of the Iron Guard against the totalitarian government of Antonescu failed. During the three-day coup, the Iron Guard murdered at least 120 Bucharest Jews in a pogrom between January 21 and 23, most of them in a forest near Jilava .

From April 1944, Bucharest came within range of the American and British air forces. On April 4, 1944, the first major attack by the 15th US Air Force took place . 875 tons of bombs were dropped. The main train station (Gara de Nord) was also bombed. Some of the bombs fell in residential areas in high winds. There were many civilian casualties. The data on the victims vary between 2000 and 5000 dead, with the number of 2942 dead and 2126 injured being given as the official number.

Another heavy attack by the British Royal Air Force followed on April 15 , this time with incendiary bombs. The Bucharest University was also badly damaged. Towards the end of the war, Romania allied itself with the Allies through a coup d'état by King Michael on August 23, 1944. Adolf Hitler then ordered the bombing of Bucharest that same night, which continued the following night. 182 people were killed. Many government buildings and historical buildings were damaged or destroyed. A day later Romania declared war on Germany. After the Red Army marched into Bucharest on August 31, there was an armistice between Romania and the Soviet Union on September 12, 1944 .

As a result of disputes in 1945 between the new Prime Minister Petru Groza and King Michael I , the latter refused to sign any laws, whereupon Groza decided to put the laws into force without a royal signature. In connection with this, there was an anti-communist demonstration in front of the Royal Palace in Bucharest on November 8, 1945 . Many arrests, injuries and deaths resulted from the violent dissolution of the demonstration.

From the Second World War to the present

In the four decades after World War II, the city grew to more than double its population. Especially in the peripheral areas, Bucharest became a huge construction site. The city area tripled in this time to 21,700 hectares. In particular, farmers were drawn to the city, who found their new jobs here in the large industrial companies. They brought their rural way of life with them to the metropolis and still determine their image today. In order to be able to meet the strong demand for housing, the communist government launched an extensive housing program.

The so-called Bucharest Declaration (“Declaration for Ensuring Peace and Security in Europe”), which was adopted by a Warsaw Pact conference from July 4 to 6, 1966, received international attention .

On March 4, 1977, an earthquake shook the area around Bucharest. Over 1,500 people died in the process. The historic structure was also partially destroyed by the tremors. With the clean-up work, a new phase of urban development began, which was characterized by a radical reconstruction of the inner city. Because after the earthquake, Nicolae Ceaușescu saw the possibility of almost completely replacing the traditional urban structure of large inner-city areas with a colossal political and administrative center. In their place came new symbols of a monumental show of power. The core and dominant element is the Parliament Palace , which around 20,000 workers were involved in building. The city also received a functioning subway.

In mid-December 1989, the popular uprising against Nicolae Ceaușescu began in Timișoara . This reached Bucharest on December 21, because the Ceaușescu regime ordered a public rally in front of the Central Committee of the Romanian Communist Party to show their support among the population after the unrest in Timișoara. However, the state-organized demonstration turned into the opposite. Securitate troops, snipers and army units equipped with tanks massacred the indignant crowd within a day. Fires broke out in the former royal palace and in the university library. A day later, on December 22, 1989, the state television broadcaster TVR announced Romania as exempt. In Bucharest alone there were around 500 deaths. After the uprising, it turned out that there are some bunker systems and tunnels in Bucharest, some of which date from the Middle Ages. For example, an escape tunnel leads from the former Central Committee building from the Calea Victorei zone to the Universitate subway. The Parliament Palace also has a large bunker with various exits. A year later protests broke out again on the University Square against the election of Ion Iliescu as Romanian President. However, the demonstrations were violently broken up by the miners from the Jiu Valley who had been summoned (" Mineriades ").

On 30./31. In May 1990 two earthquakes measuring 6.7 and 6.0 respectively shook the city. In 1995 Bucharest became the permanent seat of the SECI . At the end of the 1990s, Pope John Paul II visited the Romanian capital during his visit to Romania. At a celebration of reconciliation between the Orthodox and Catholic Churches, the Pope symbolically presented Patriarch Teoctist I on the central Bucharest Piața Unirii with a notable donation for the construction of the largest Orthodox cathedral on the Piața Unirii.

The intensive construction activity in the historic old town since the turn of the millennium has been done in part at the expense of the historical building fabric. For many, the Cathedral Plaza office tower is a symbol of this conflict .

In 2006 the 11th Summit of the International Organization of Francophonie took place in Bucharest . In the year of Romania's accession to the EU, the fifth Patriarch Teoctist I died. Four days after his death, on August 3, 2007, he was buried in the Patriarchal Church . In the period from April 2nd to April 4th, 2008, the city hosted the XX. NATO summit.

A fire disaster occurred in Bucharest at the end of October 2015 . 64 people were killed and 147 injured, some seriously. The government then ordered a three-day state mourning. On March 12, 2016, the Spring Palace was opened to the general public for the first time, "so that the people can make their peace with history," said the Minister for Dialogue with Civil Society, Violeta Alexandru. The palace with garden was built in 1964/65 according to the ideas of Nicolae Ceausescu, who ruled from 1965 to 1989 and lived in the luxury residence with 80 rooms, cinema, pool and bunker for just as long with his wife and three children. After the overthrow, the palace was used to accommodate state guests.

population

Population development

The population of the city increased continuously from 1778 to 1992. Bucharest has always attracted large numbers of job seekers, which has resulted in rapid population growth in the city. In particular, the planned economic development of the Ceaușescu era led to a sharp increase in population, which required the construction of new city districts. Migration began in the first half of the 1990s. Many of the workers who immigrated in the 1980s and became unemployed in the following decade returned to their places of origin. Since around 1995, many (especially wealthy) Bucharest residents have moved to the rural surroundings of the city.

Bucharest has 1.9 million inhabitants, making it by far the most populous city in Romania. Around half of Romanian street children live in Bucharest . They can not be overlooked at București Nord train station or stations like Piața Victoriei, but there has been a significant decline in recent years.

|

|

|

|

The ethnic structure of the population in the city is extremely homogeneous. According to official statistics (2002) 97% are ethnic Romanians. The second largest group are the Roma with 1.4% (= 27,322 people). The population shares of the next larger groups, such as 0.3% Hungarians and 0.1% Romanian Germans , Jews , Greeks , Russians and Lipovans , Turks and Chinese , are only small. Another 0.4% belong to other ethnic groups (mainly Bulgarians , Armenians , Albanians , Italians , Ukrainians and Poles ). The average annual population growth is −0.7%. 11.6% of the population are under 15 years old, 5.9% are over 75 years old.

Religions

The cityscape is characterized by Romanian Orthodox sacred buildings. In 1885 there were already 124 churches in the city, meanwhile there are still around 100 churches in Bucharest. The most famous are the Curtea Veche Church (1545–1554), the Patriarchal Church (1654–1658), the Stavropoleos Church (1724), the Domnița Bălașa Church (1751), the Roman Catholic Cathedral of St. Joseph (1883) and Greek Catholic St. Basil's Cathedral (1909).

In 2002, 96.05 percent of Bucharest's residents committed themselves to the Romanian Orthodox Church . The largest church in Romania is subordinate to SS Daniel Ciobotea in Bucharest , who is the sixth patriarch in office since 2007.

In the same year, 1.21 percent of the population were Roman Catholic . The Archdiocese of Bucharest was established on April 27, 1883 when the Apostolic Vicariate of Wallachia was elevated to an Archdiocese . On June 5, 1930 , as a result of the signing of the Concordat between the Romanian State and the Holy See , the Archbishop of Bucharest was elevated to Primate of Romania .

The Evangelical Lutheran Church in Romania was founded in 1921 as the “Synodal Presbyterial Evangelical Lutheran Church” and until 2001 was called the “Evangelical Synodal Presbyterian Church AB in Romania”.

In Bucharest there is the world's only Romanian-speaking Lutheran congregation with around 70 members, which can be traced back to the Jewish Christian Richard Wurmbrand , among others .

In 2002, 0.49 percent of the Bucharest population professed the Muslim faith. 0.39 percent of the population were of Romanian Greek Catholic faith. The Jews represent approximately 4,000 members, one of the largest ethnic communities in Bucharest. Since 1990, this national minority in the cultural and political spheres by the Federation of Jewish Communities in Romania, represented with headquarters in Bucharest. The Jewish cemetery in the Romanian capital has 35,000 graves.

politics

Politics and administration

Bucharest has two administrative levels. The city administration (Primăria Generală) subordinate to the Lord Mayor is responsible for the entire city. Their competencies include water supply, public transport and main roads.

The mayors and administrations in the six sectors of Bucharest are responsible for secondary roads, schools and garbage disposal, among other things.

In the local elections of June 2016, the distribution of seats for the city council was as follows:

| Political party | Mandates |

|---|---|

| PSD (Social Democratic Party) + UNPR (National Unit for the Progress of Romania) | 24 |

| USB (Union Save Bucharest) | 15th |

| PNL (National Liberal Party) | 8th |

| PMP (People's Movement Party) | 4th |

| ALDE (Party of the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats) | 4th |

| total | 55 |

Of the six mayor offices in the Bucharest sectors, all are provided by the PSD . The new Lord Mayor Gabriela Firea also belongs to the PSD and was elected with 42.97% of the vote.

The mayors are directly elected every four years.

coat of arms

The coat of arms of Bucharest was designed in the 19th century under Alexandru Ioan Cuza and has been changed several times up to the present day. In 1868 the coat of arms consisted of a wall crown with seven towers, a coat of arms shield with the saint and today's city patron Sfântul Dimitrie cel Nou , not to be confused with Sfântul Dimitrie ( Demetrios of Thessaloniki ), and the inscription: PATRIA ȘI DREPTUL MEU (Romanian for: “Das Fatherland and my right ”). The coat of arms was exchanged for another coat of arms under Nicolae Ceaușescu in the period from 1970 to 1989.

The city coat of arms, which has been in effect since 1994, took over the wall crown with seven towers, the coat of arms shield with Saint Dimitrie Basarabov and the above-mentioned inscription. There was also the state flag with the same inscription, a golden eagle with a blue crown, sword and Latin cross, and an eagle with a Latin cross in its beak, which is enthroned on the top of the wall.

Town twinning

Bucharest has partnerships with the following cities:

-

Amman ( Jordan ), since 1999

Amman ( Jordan ), since 1999 -

Ankara ( Turkey )

Ankara ( Turkey ) -

Athens ( Greece ), since 1993

Athens ( Greece ), since 1993 -

Atlanta ( USA ), since 1994

Atlanta ( USA ), since 1994 -

Bethlehem ( Palestinian Territories ), since 1996

Bethlehem ( Palestinian Territories ), since 1996 -

Beijing ( People's Republic of China ), since 2005

Beijing ( People's Republic of China ), since 2005 -

Budapest ( Hungary ), since 1997

Budapest ( Hungary ), since 1997 -

Chișinău ( Moldova )

Chișinău ( Moldova )

Culture and sights

Cityscape

The cityscape of Bucharest is characterized by a diverse architecture with a colorful mix of styles in a small space. After the Turkish sultanate, architecture turned to western styles. Models were Paris and the Austrian monarchy. In addition to palaces in the French eclectic-academic style of the late 19th century, there are villas in the neo-Romanian Brâncoveanu style of the early 20th century, which combines oriental and Italian architectural motifs. Small rural houses crouch between blocks in the Bauhaus style of the 1930s and typical socialist prefabricated buildings from the 1960s and 1970s. In addition, there is the confectioner style from Nicolae Ceaușescu's last years in office .

The center of this new and still unfinished district is the former “ House of the People ”, which the Bucharest people called the “House of Victory over the People”. The Romanian parliament, conference centers and a museum are located in this gigantic step pyramid. Next door, Romania's largest Orthodox cathedral, the Cathedral of the Redemption of the People , is expected to be completed by the end of 2018.

The old town is located between Union Square (Piața Unirii), Cişmigiu Park , the National Opera and Revolution Square. A fifth of the old town was demolished to make way for the new socialist center, the Centrul Civic . Kilometers of boulevards (especially the boulevard Unirii , which is 60 meters longer than the avenue des Champs-Élysées ), lined with neo-Stalinist blocks of flats for the nomenklatura , and ornate fountains characterize the picture here.

However, four fifths of the old town remained untouched. In Bucharest, apart from a few major axes on which the nobles used to erect their palaces and representative buildings, there are also grown quarters with crooked streets, small, old (sometimes decaying) houses and lots of greenery.

In 2007, single-family houses were the dominant form of living in Bucharest. Around three quarters of the total of 115,000 residential buildings are single-family houses. Apartment blocks make up around 12%. In 2007 there were around 785,700 apartments in Bucharest. Estimates assume that around 10% of the apartments are vacant. Most of the buildings in Bucharest are in poor structural condition.

Buildings

The current Arcul de Triumf (Triumphal Arch) was built after the First World War. At the end of Kiseleff Avenue, a temporary monument was erected in 1878 after the country had gained independence. This structure was replaced in 1922 by a larger but still temporary one made of wood and stucco - whereupon the famous Romanian musician and composer George Enescu wrote a mocking letter to the mayor asking when the capital would one day get a real triumphal arch. Said “permanent” triumphal arch was then completed in 1935 to 1936 by Petre Antonescu to form a huge building in the classical Roman style and inaugurated on December 1, 1936 on the national holiday - an example that decades of bombastic temporary arrangements have a tradition in Bucharest. The Arcul de Triumf is decorated with numerous entries and remarkable reliefs. Well-known sculptors such as Frederic Storck , Ion Jalea and Cornel Medrea have contributed to the manufacture of this monument. As in Paris, the traffic flows in a star shape from a series of large streets towards the mighty arch.

The Romanian Athenaeum was built between 1885 and 1888 according to the plans of the architect Albert Galleron. The concert hall, which is now the seat of the George Enescu State Philharmonic, is located in the dome-roofed rotunda. The concert hall has 652 seats. The fresco on the inside of the drum of the dome is by Costin Petrescu and depicts the highlights of Romanian history from Roman times. Between the columns of the portico there are portraits of important princes of history on subsequently added round gold mosaics. In front of the portal is a bronze statue of Mihai Eminescu (Romania's poet prince).

The Bucharest Royal Castle (Palatul Regal) has a U-shaped floor plan. The building was built from 1927 to 1937 according to plans by Nicolae Nenciulescu in the neo-classical style. The Romanian King Michael I lived here until 1947. Since 1950, the National Art Museum of Romania (Muzeul Național de Artă al României) has been housed in a part of the building. After 1947 the communist rulers of Romania moved into the other part of the monumental palace complex. On December 22, 1989 , at 11:30 a.m., Ceaușescu tried to speak one last time to the people gathered in front of the ZK building from a balcony of the huge complex on which the Central Committee building was then. Shortly afterwards, the Ceaușescus had to flee from the roof of the building by helicopter. The scene became world famous through television broadcasts.

The Victoria Palace on Victory Square , seat of government since 1990, was built in 1937–1944. In communist times it housed the Council of Ministers and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

In the side street Strada Iuliu Maniu you come across the remains of the first Bucharest prince's court Curtea Veche (Old Court) from the 15th and 16th centuries. In the 17th century the prince's court reached an area of 25,000 square meters. Curtea Veche was later destroyed by fires and earthquakes. The remains, discovered in 1958, consist of a few ruins and the four hundred -year- old three-cornered old courtyard church (Biserica Curtea Veche) . The leaf and flower ornamentation of the later added Brâncoveanu portal is also impressive.

The Hanul lui Manuc is a well-preserved medieval tavern . Today's hotel and restaurant is the only former caravanserai from the beginning of the 19th century that has survived in the city. The building was erected in 1808 by the Armenian businessman and politician Manuc Bei on a building plot that was auctioned in 1798 and which previously belonged to the former royal court. The Bucharest Treaty between Russia and Turkey was signed in the tavern in 1812 . In 1880 a hall was built in the hostel, in which numerous workers' meetings subsequently took place.

The Parliament Palace ( Romanian Palatul Parlamentului ), also known as the House of the People ( Romanian Casa Poporului ), is one of the largest buildings in the world . Its floor area is 65,000 square meters, the built-up area 265,000 square meters. The largest hall in the building is 16 meters high and 2200 square meters. It is located at the mouth of the three and a half kilometers long main thoroughfare in downtown Bucharest, the Bulevardul Unirii . At 22 Bulevardul Unirii is the Romanian National Library ( Romanian Biblioteca Națională a României ), the largest library in Romania.

Church buildings worth seeing include the Patriarchal Cathedral (Catedrala Patriarhală), the Patriarch's Palace , the Stavropoleos Church , the Church of the Annunciation (Curtea Veche), the Kretzulescu Church and the Roman Catholic St. Joseph's Cathedral . Since 2010 the new Cathedral of the Redemption of the People , one of the largest Orthodox churches in the world , has been built next to the Parliament Palace.

Other notable buildings are the Cretzulescu Palace , the Palace of Justice, Mogoşoaia Palace , Cotroceni Palace and the Monument to the Heroes of the Air .

The Bucureşti Mall has existed since 1999.

Museums, galleries

At the beginning of the 19th century the first museums were founded in the city. Bucharest already had 39 museums and collections in the 1970s. Since 2005 the city has organized an art biennale , the Bucharest Biennale .

The Natural History Museum Grigore Antipa is the largest such museum in Romania. Founded in 1834, it had nearly 300,000 exhibits in the 1970s. With 82,000 specimens, the museum has one of the most important and richest butterfly collections in the world. The museum currently has more than 2 million exhibits.

In 1951 the European Gallery was opened. In the 15 museum halls you will find sculptures and paintings by famous Romanian and foreign artists such as Titian, Rembrandt, Veneziano, Tintoretto, Zurbaran, El Greco, Renoir, Monet, Pissarro, Breughel, Delacroix, Sisley and Rubens.

The Muzeul Național de Artă al României (National Art Museum of Romania) is located in the former royal palace (Palatul Regal), which was completed in 1937. In 1948, after the abolition of the monarchy, the palace became the seat of the National Art Museum. The museum opened two years later. It houses the National Gallery with over 70,000 exhibits. The collection shows Romanian paintings from Nicolae Grigorescu to Camil Ressu, masterpieces by Italian, Dutch, Spanish and Russian artists as well as late Byzantine icons and modernist sculptures.

Collections and exhibitions from prehistory to the 20th century can be found in the National Museum of the National History of Romania . Among other things, the extensive treasury with valuable objects from all eras is famous. The museum is located in the building of the former Post Palace.

The Zambaccian Museum (Romanian: Muzeul Zambaccian) in Bucharest is a museum in the former home of Krikor Zambaccians (1889–1962), an Armenian businessman and art collector. Here you can see the only Cézanne painting in Romania as well as an important collection of Romanian painters.

The George Enescu Museum is located in Calea Victoriei . The museum is housed in the French-inspired Art Nouveau palace of the landowner, prime minister and head of the Conservative Party, Gheorghe Grigore Cantacuzino , built between 1901-03 . The palace was later briefly the home of the Romanian composer Enescu.

The National Museum of Contemporary Art (MNAC, Muzeul National de Arte Contemporanea) is located in a part of the Parliament Palace.

The Romanian State Railways operate a small railway museum (Muzeul CFR) with a model railway system H0 at Bucharest Nord station (platform 14).

Outside the center is the village museum (Muzeul satului). It maintains innumerable, well-preserved houses from different eras. Since it opened in 1936, you can find centuries-old farmhouses and wooden churches from all over Romania as well as more than 50 households, workshops and mills.

Other well-known Bucharest museums are the Cercul Militar Naional Museum, the Gheorghe Tattarascu Museum, the Theodor Pallady Museum and the Jewish Museum (close to the center in the former Schneider Synagogue ).

Parks

In addition to a number of lakes on the outskirts of the city, Bucharest also has some parks. The oldest park in Bucharest is the approximately 17 hectare Cişmigiu Park (officially: Grădina Cişmigiu , also Cişmigiu Garden). The first work on the park area began in 1798 and lasted for several decades. The Viennese garden architect Meyer was entrusted with the creation of an extended park in 1849. In 1910 the park was given its final look by the architect Friedrich Rebhuhn. Cișmigiu has a French garden, the “writers' area”, the “Roman area”, a rose garden and three lakes.

Located in the north, Parcul Regele Mihai I al României (long Herastrau Park ) is the largest amusement area in Bucharest, with an area of 187 hectares. With well-kept avenues and flower beds, with statues, columns, bridges and thousands of willows , the park has an overwhelming effect due to its size.

At the southern end of the Bǎneasa Forest, just outside the north of Bucharest, lies the almost 6 hectare zoological garden of Bucharest , which was opened in 1955.

Overall, however, the proportion of green space in Bucharest fell by 50% between 1989 and 2008 as a result of construction work.

theatre

In Bucharest there are 19 theaters, one operetta and the Opera Națională Bucureşti, the largest of the four Romanian national operas . The National Theater opened in 1852. Since 1973 the theater has been housed in a modern building with an area of 10,000 square meters on Nicolae Bălcescu Boulevard.

The Bucharest National Opera was founded in 1919. It has been housed in a new building since 1953 and is a repertoire company for opera and ballet. The current repertoire consists of over 150 opera and ballet performances.

In 1946 the Teatrul Odeon was founded. The Majestic room has a sliding ceiling that is unique in Europe. Today's Nottara Theater was founded in 1947 under the name Army Theater. The Teatrul Bulandra was built in the late 1940s. It is located on Jean-Louis-Calderon-Strasse. In 1961, Romanian actor Radu Beligan founded the Comedy Theater on Sfântu Dumitru Street.

Streets, places

The Lipscani Zone (German: Leipziger Zone) is a street and a district near the Piața Unirii. The district was an important trading zone in the Middle Ages. The first alley in Bucharest that was mentioned in a document was initially called “Große Gasse bei alten Fürstenhof” and later “Deutsche Gasse”. Its current name comes from the second half of the 18th century. At that time there were shops of mostly Transylvanian traders who offered goods from Leipzig. The medieval architecture is still preserved. New archaeological finds are being made there. There is a large concentration of cafes and bars in the Lipscani zone.

Calea Victoriei is also one of the oldest boulevards in Bucharest . The road built by the ruler Brâncoveanu connects the Piața Splaiului with the Piața Victoriei. It was built to have a straight driveway to the Mogoșoaia Palace . It was given its current name in 1877 to commemorate the victory of the Romanian army in the War of Independence. Until the end of the 19th century, this city's artery was used almost exclusively by the sovereigns and courtiers. In the Calea Victoriei, palaces and magnificent buildings such as the Cantacuzino Palace (the museum of George Enescu), the Ateneul Român (Romanian Athenaeum) or the Palatul Regal (Bucharest Royal Castle) are lined up.

The Bulevardul Unirii (Boulevard of Unity) is the current name of the former Boulevard of the Victory of Socialism , which the Romanian dictator Nicolae Ceaușescu had laid out in the 1980s.

Culinary specialties

In the numerous restaurants and localities, dishes from international and local cuisine are served. However, there are no original Bucharest specialties that are not offered elsewhere. Romanian cuisine is a symbiosis of the experiences of a rural culture with its occupants. The Romanian taste demands were influenced by numerous variants of the Balkan cuisine, the cuisine of the Viennese Empire, the Hungarian and German cuisine. One of the most popular dishes is mămăligă , a corn porridge that has long been considered poor people's food . Main dishes are the cabbage wraps with meat ( sarmale ) , the mousakas , the șnițel ( Wiener Schnitzel ), game as roast and tochitură . Various cakes, plăcintă (from Latin: placenta) and meatballs (chiftele) (with garlic, black pepper and savory) are also offered. A grill specialty that can be found everywhere is the mititei or mici , a form of Ćevapčići that is eaten with mustard or hot paprika. Local specialties also include soups and stews such as tripe soup , but also bean soup, vegetable soup, beef and chicken soup, as well as zacuscă , a sauce made from peppers, aubergines and tomatoes, and the homonymous stew Zacuscă made from tomatoes, aubergines, vegetable onions and peppers (possibly. also with beans or mushrooms).

Sports

Bucharest has various sports facilities. Until the end of 2007, the Lia Manoliu Stadium in Bucharest was the largest stadium in Romania. According to official information, it offered space for 60,120 people and was demolished in 2008 to make way for the new Arena Națională , which was completed in August 2011 . The 2012 UEFA Europa League final took place in the new arena . Over the course of its history, the city has repeatedly hosted world and European championships.

World and European championships

Bucharest hosted the three-nation rugby tournament in 1938 , the 20th table tennis world championship in 1953 , the women's volleyball championship in 1955 , the first women's gymnastics championships in 1957 , the world wrestling championships in 1967 and the European wrestling championships in 1979 , The European Boxing Championship in 1969 and the European Volleyball Championship in 1955 and 1963 .

Soccer

There are five major football clubs in Bucharest. Sportul Studențesc is the oldest of these. It was founded on February 11, 1916 by the mathematician Traian Lalescu . One of the club's greatest successes was winning the Balkan Cup. The club plays its home games in the Stadionul Regie .

Rapid Bucharest (officially: Fotbal Club Rapid Bucureşti) was founded on June 11, 1923 by railway workers (see also: CFR ). Today's second division is the only Romanian pre-war club that was not dissolved by the communist post-war regime. The home stadium of Rapid Bucharest is the Giuleşti-Valentin Stănescu Stadium .

In 1944 the football club FC Progresul Bucharest was founded. The club has had numerous different names throughout its history. The club's home ground, the Cotroceni Stadium, can seat 14,452 spectators. The current club Liga 4 won the Romanian Cup in 1960 and the Romanian runner-up in 1996, 1997 and 2002.

Steaua Bucharest / FCSB Bucharest , one of the most successful Eastern European football clubs, was founded in 1947. In 1986 it was the first Eastern European club to win the European Champion Clubs' Cup and the European Supercup.

The football club Dinamo Bucharest (officially: Fotbal Club Dinamo Bucureşti) founded on May 14, 1948, is a very successful Romanian football club. The club's home games are played in Dinamo Stadium . The Liga 1 club was eighteen times Romanian champions, twelve times Romanian cup winners and once Romanian Supercup winners.

tennis

The international tennis tournament ATP Bucharest took place in Bucharest every autumn . However, it has not been held there since 2016.

Racing

In May 2007, a racing event was held on the Bucharest Ring for the first time . The temporary race track is 3180 meters long. It leads in an irregular square clockwise around the Parliament Palace.

Economy and Infrastructure

Bucharest is the most important economic center in Romania. Almost all of the major service companies in Romania, especially banks and financial firms, are based in Bucharest. According to a study from 2014, the greater Bucharest area generated a gross domestic product of 72.4 billion US dollars ( PPP ). In the ranking of the economically strongest metropolitan regions worldwide, he came in 178th place. The GDP per capita was $ 38,635, much higher than the rest of the country.

By the end of 1971, the total volume of Bucharest's industrial production was 17.3 percent of the national production. At that time there were 235 industrial plants in operation, 175 of them of national importance. The most important industry, accounting for 39.3% of the city's total production, was the engineering and metalworking industries.

The region around Bucharest is mainly characterized by the mechanical and electrical engineering industries. Since the 1990s, increasing efforts have been made to attract multinational corporations.

On January 1, 2006, 2.215 million people lived in Romania's richest economic region, Bucharest-Ilfov, or around 12 percent of the Romanian workforce. In 2005 and 2006 they achieved a growth rate of 7.3 and 7.8 percent, which is above the national average. The region also handled 20 percent of Romanian exports and 40 percent of imports. Unemployment in the region was 2.3 percent in 2006. An employee in the Bucharest-Ilfov region earned an average of 977 lei in 2005, almost a third more than in the rest of the country.

The Bucharest Exhibition Center (Complexul Expozițional ROMEXPO) is the largest exhibition complex in Romania. The total area of the facility is 421,700 m². The exhibition grounds have 42 halls and 2,200 parking spaces. Over 40 trade fairs take place on the site every year.

The larger companies based in Bucharest include, among others, Dacia , a Romanian automobile manufacturer that belongs to Renault, FAUR SA, a Romanian vehicle and machine manufacturer, Softwin, one of the leading European companies for security software and services for data security, and the Romanian oil company. and gas company Petrom . The company is listed in the BET 10 share index. The Bucharest Stock Exchange (Romanian: Bursa de Valori Bucureşti ) is the stock exchange of Romania . It was established on April 21, 1995 in the Bank of Romania building.

In a ranking of cities according to their quality of life, Bucharest took 107th place out of 231 cities worldwide in 2018.

Planned major projects

The following major projects are under construction or in preparation in Bucharest.

| Project | value | As of 2016 | annotation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carpathian Highway , (Bucharest- Brașov ) | around 1.4 billion euros | The Bucharest - Ploieşti section was opened on July 19, 2012. | The inner-city section up to Centura București is to be completed by the end of November 2017. |

| Metro expansion project in Bucharest, Line V | 1 billion euros | The start of construction for the new M5 line from Ghencea via Eroilor and Universitate to Pantelimon was in autumn 2011. Completion should take place in stages. | The opening of the Ghencea - Eroilor section with ten stations has been postponed to 2017 [out of date] . |

traffic

Bucharest has two civil airports . Henri Coandă in Otopeni is the largest and most important airport in Romania. The older and significantly smaller, but closer to the city center, Băneasa Airport , once the home destination of Blue Air and the destination of other low-cost airlines such as Germanwings and Wizz Air , has been reserved for business travel since March 2012.

As the largest transport hub in Romania, Bucharest has the international Gara de Nord train station . Local trains operated by the Căile Ferate Române state railway as well as long-distance and international trains run here. Many of the country's main lines begin or end in Gara de Nord. In Bucharest there are also several regional train stations (Progresul, Obor) and the București Triaj marshalling yard, which has already been partially closed .

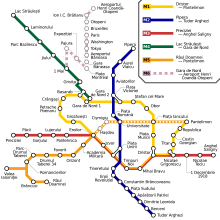

Around a million commuters visit the capital every day. The city has a well-developed underground, tram, trolleybus and omnibus network. The Bucharest Metro opened on November 16, 1979. The four Bucharest underground lines are together 62.5 kilometers long and serve 45 stations. The metro is operated by Metrorex, the tram, trolleybus and omnibus network by the transport company Societatea de Transport Bucureşti (STB). In 2006 the STB. Serves 25 tram lines. The bus system is the densest of all Bucharest modes of transport. 101 STB bus routes are served by 1000 buses, most of which operate in the immediate metropolitan area of Bucharest. In addition, some buses go to the cities and villages that border Bucharest. The trolleybus network of the STB. covers an additional 20 additional lines. The bus network has been expanded since 2005. For this reason, the city of Bucharest put 500 new low-floor buses into operation in 2006 and 2007 . Another 500 low-floor buses have been delivered since the beginning of 2008. The other modes of transport have also been or are being modernized; they have also procured new trolleybuses and underground trains and started to move some tram lines to their own tracks (known as metrou ușor , light rail). A single trip on an STB means of transport cost 1.30 lei (~ 0.35 euros) in 2014, a trip with the metro 2.50 lei.

There is a year-round driving ban in Bucharest between 7:00 a.m. and 9:00 p.m. for trucks over 7.5 tonnes gross vehicle weight. For the period from September 15 to June 15, access is permitted with a special permit. The Romanian motorway network is only just being established. The first Romanian motorway (Romanian autostradă, plural autostrăzi) was the 113 km long Bucharest – Piteşti route, which was built in the 1960s. The route is part of the A1 .

Cycle paths have been laid out along many of the main roads, for example Calea Victoriei or Bulevardul Kiseleff. The only noteworthy pedestrian zone in Bucharest is in the Lipscani district.

media

After the Romanian Revolution, the number of private media in Bucharest rose within a short time. The national broadcasting company, the national news agency and the public television company TVR with the channels TVR 1, TVR 2, TVR 3, TVR HD and TVR Internațional remained in state hands . TVR 1 also broadcasts a one and a half hour program in German every week. The national daily newspapers based in Bucharest include Adevărul , Cotidianul, România liberă and Evenimentul Zilei. Until 1992, the newspaper published in Bucharest for the German-speaking minority in Romania was called Neuer Weg . In 1993 it was renamed the Allgemeine Deutsche Zeitung for Romania . The ADZ is the only German daily newspaper in Eastern Europe.

education

The city is home to 16 state and twelve private universities, five colleges and numerous academies, research and educational institutions. The Romanian Academy is also located in Bucharest . The highest forum of science and culture in Romania was founded in 1866 and has 181 members elected for life.

The Bucharest Business Academy (Romanian: Academia de Studii Economice din București, ASE for short) is the city's largest university. It is a state economic university with a total of 49,000 students and around 2,000 academic employees. King Carol I founded the university in 1913.

The University of Bucharest is a state university with 30,000 students and 18 faculties. Your main building is on Universitätsplatz . The Polytechnic University of Bucharest currently has 13 faculties with a total of around 15,000 students and over 4,000 academic staff.

In 1854, the Technical University of Construction Bucharest (Romanian: Universitatea Tehnică de Construcții București, UTCB for short) was founded. Almost 10,000 students study at the technical university with six faculties. The Carol Davila Medical and Pharmaceutical University (Romanian: Universitatea de Medicină și Farmacie Carol Davila) with three faculties was founded three years later. The oldest agricultural college in the country is the Universitatea de Științe Agronomice și Medicinã Veterinarã București (USAMV, German: University of Agricultural Sciences and Veterinary Medicine), founded in 1852 . The National University of the Arts Bucharest (Romanian: Universitatea Națională de Arte București - often abbreviated as UNArte) is the most important art school in Romania. It was founded on October 5, 1864 by Prince Alexandru Ioan Cuza . In the same year the Ion Mincu University of Architecture and Urban Planning was founded .

Several private universities have also been founded in the last few decades. This includes the University of Titu Maiorescu, founded in 1990 (Romanian: Universitatea Titu Maiorescu) with six faculties, and the Romanian-American University founded in 2004 (Romanian: Universitatea Româno-Americană, English: Romanian-American University). One of the major academies based in Bucharest is the Technical Military Academy Bucharest (Romanian: Academia Tehnică Militară din București), founded in 1949 . The academy is a military training facility for the Romanian armed forces.

The National Music University Bucharest (Romanian: Universitatea Națională de Muzică Bucureşti ) was founded in 1864 by a decree of Prince Alexandru Ioan Cuza . Mihail Kogălniceanu signed the charter in his capacity as prime minister.

Personalities

- sons and daughters of the town

Bucharest was the birthplace of numerous well-known personalities. These include the tennis player Angelica Adelstein-Rozeanu , the writer Marthe Bibesco , the opera singer Nicolae Herlea , the composer Maia Ciobanu , the music producer Michael Cretu , the chemist Lazăr Edeleanu , the writer Dora d'Istria , the pianist Clara Haskil Peter Herbolzheimer , the band leader , the actor and filmmaker John Houseman , the doctor and psychiatrist Jacob Levy Moreno , the tennis player Ilie Năstase , the physiologist Nicolae Paulescu , the athlete Mihaela Peneș , the chess player Elisabeta Polihroniade , the actor Edward G. Robinson , the gallery owner Ileana Sonnabend , the painter Hedda Sterne , the writer Hélène Vacaresco , the historian Eugen Weber and the pastor Richard Wurmbrand .

See also

literature

- Marin Mihalache: The Museums of Bucharest. Meridiane Verlag, 1963, ISBN 978-3-7025-0430-4

- Paul Jeute: Bucharest. Myths, destruction, reconstruction. An architectural history of the city. Schiller Verlag, Bonn, 2013, ISBN 978-3-944529-17-2

- Ion Marin Sadoveanu, Elga Oprescu: Turn of the century in Bucharest. Der Morgen (publisher), 1964

- Merian: Bucharest and Romania's Black Sea coast. Issue 6 / XIX, Hoffmann and Campe, June 1966

- Sebastian Bonifaciu, Emanuel Valeriu (scientific subject: Șerban Cioculescu, Grigore Ionescu): Bucharest from A to Z. Pontica handbooks, publishing house for tourism, Bucharest 1974

- Constantin C. Giurescu : History of the City of Bucharest. Sports and tourism publisher, Bucharest, 1976

- Axel Barner : City Guide Bucharest. Kriterion Verlag, 1995, ISBN 973-26-0436-0

- Axel Barner: Select Europe. Bucharest. Wieser Verlag, 1999, ISBN 3-85129-284-7

- Ana G. Cast Branco dos Santos, Horia Georgescu, Pierre Levy: Modernism in Bucharest. Pustet Verlag, 2001, ISBN 3-7025-0430-3

- Joachim Vossen: Bucharest - The Development of Urban Space. From the beginning to the present. Reimer Verlag, 2004, ISBN 3-496-02753-3

- Birgitta Gabriela Hannover: Discover Bucharest - The Romanian capital and its surroundings. Trescher Verlag, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-89794-120-5

- Thomas Schares: Bucharest / Bucureşti . In: Online encyclopedia on the culture and history of Germans in Eastern Europe , 2013. URL: ome-lexikon.uni-oldenburg.de/54190.html (as of April 22, 2013).

Web links

- Private Bucharest portal (English)

Individual evidence

- ^ Population of Capital Cities in 2018 (thousands). UN , accessed on July 29, 2019 .

- ^ History of the city from July 21, 2008 .

- ↑ Merian, Bucharest and Romania's Black Sea Coast, p. 95, Issue 6 / XIX, Hoffmann and Campe (June 1966).

- ↑ Mihnea Corneliu Oncescu, Klaus-Peter Bonjer: A note on the depth recurrence and strain release of large Vrancea earthquakes , Tectonophysics 202, 1997.

- ↑ F. Wenzel: Reduction of earthquake damage - a challenge for geo- and engineering sciences, TU Berlin from July 21, 2008 ( Memento of the original from December 21, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. .

- ↑ Geotechnical and seismic microzoning of Bucharest, University of Karlsruhe from July 21, 2008 ( Memento from June 11, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 282 kB).

- ↑ Information on the Bucharest homepage , accessed on December 14, 2015.

- ↑ Michael Cismarescu: The constitutional development of the Socialist Republic of Romania 1965-1975, p. 238, in the yearbook of the public law of the present , Volume 24, 1975, ISBN 3-16-637762-X .

- ↑ Decree no. 284 din 31 Iulie 1979 ( memento from June 3, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) (Romanian).

- ↑ Birgitta Gabriela Hannover, Discover Bucharest, p. 54, 2008.

- ↑ A documentary film entitled "City of Bucur" (direction, production, screenplay Aurelia Mihai ) was funded by the German government with around € 12,500 in 2006 (see Press and Information Office of the Federal Government, press release No. 124: Minister of State Neumann awards production grants for short films ( Memento of September 27, 2013 in the Internet Archive )).

- ↑ Gerrit E. Ulrich: A song from the land in the sea of houses in the city , p. 4, from Merian, Bucharest and Romania's Black Sea coast, volume 6 / XIX, Hoffmann and Campe (June 1966).

- ↑ Guide to Bucharest (PDF) of July 21, 2008 ( Memento of November 13, 2011 in the Internet Archive ).

- ↑ Official homepage of Bucharest (www.pmb.ro) of July 21, 2008 ( Memento of the original of February 21, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. .

- ^ Sebastian Bonifaciu, Emanuel Valeriu: Bucharest from A to Z, p. 13, Pontica handbooks, Verlag für Tourismus, Bucharest (1974).

- ↑ Klaus Kreiser: The Ottoman State 1300-1922 , Oldenbourg 2000, p. 21.

- ^ Joachim Vossen: Bucharest - The development of urban space. From the beginning to the present .

- ^ Sebastian Bonifaciu, Emanuel Valeriu: Bucharest from A to Z, p. 13.

- ↑ Joachim Vossen conjectures : Bucharest, Uni Klagenfurt on September 11, 2008 ( Memento of February 13, 2009 in the Internet Archive ).

- ↑ Birgitta Gabriela Hannover, Discover Bucharest, p. 42, 2008.

- ^ Sebastian Bonifaciu, Emanuel Valeriu: Bucharest from A to Z, p. 16.

- ^ Sebastian Bonifaciu, Emanuel Valeriu: Bucharest from A to Z, p. 17.

- ^ Meyers Konversationslexikon, fourth edition, 1885-1892 .

- ↑ Birgitta Gabriela Hannover, Discover Bucharest, p. 44, 2008.

- ^ Sebastian Bonifaciu, Emanuel Valeriu: Bucharest from A to Z, p. 18.

- ^ Sebastian Bonifaciu, Emanuel Valeriu: Bucharest from A to Z, p. 21.

- ^ Sebastian Bonifaciu, Emanuel Valeriu: Bucharest from A to Z, p. 22.

- ^ Sebastian Bonifaciu, Emanuel Valeriu: Bucharest from A to Z, p. 23.

- ↑ a b c Sebastian Bonifaciu, Emanuel Valeriu: Bucharest from A to Z, p. 24.

- ↑ Horst G. Klein, Katja Göring: Romanische Landeskunde, p. 76, Gunter Narr Verlag, 1995, ISBN 3-8233-4149-9 .

- ↑ Birgitta Gabriela Hannover, Discover Bucharest, p. 48, 2008.

- ^ The Bucharest Pogrom, January 21-23 , 1941. The Nizkor Project.

- ^ Radu Ioanid: The Antonescu Era. In: Randolph L. Braham (Ed.): The Tragedy of Romanian Jewry. The Rosenthal Institute for Holocaust Studies, Columbia University Press, New York 1994, p. 126.

- ↑ Hans Rothfels and Theodor Eschenburg: “Quarterly Books for Contemporary History” at ifz-muenchen.de PDF 5.8 MB.

- ↑ Narcis Ionuţ Gherghina: History of American bombings (page 43) at scribd.com (Romanian).

- ^ Sorin Marin: The social consequences of the 1944 Anglo-American bombing of Ploieştis at etd.ceu.hu PDF 2.2 MB (English).

- ^ Ottmar Traşcă: Bombing of Romania by the British and American air forces from April to August 1944. at history-cluj.ro (Romanian).

- ↑ English and American bombs , at jurnalul.ro, July 3, 2006 (Romanian).

- ↑ Constantin C. Giurescu, "Istoria Bucureştilor. Din cele mai vechi timpuri pînă în zilele noastre" ("History of Bucharest. From the earliest times to the present day"), Ed. Pentru Literatură, Bucharest, 1966.

- ↑ Narcis I. Gherghina: German Luftwaffe bombed Bucharest on 23 to 26 August 1944 at aviatori.ro (Romanian).

- ↑ Axel Barner: Bucharest image in the German-language contemporary literature of July 21, 2008 (online) ( Memento of the original of May 17, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. .

- ↑ Manfred Görtemaker: From the Cold War to the Era of Relaxation, bpb.de of August 9, 2008 .

- ↑ Earthquake-proof construction - unique test set-up inaugurated in Bucharest, Uni-Protocol dated July 21, 2008 .

- ↑ Huge Parliament Palace in Bucharest's city center . In: KLM.com . ( klm.com [accessed March 17, 2017]).

- ↑ Armin Heinen: The death of the dictator and the present of the past Romania 1989–2002, Zeitblicke.de (PDF; 307 kB) of July 21, 2008 .

- ↑ Romulus Cristaea: Doar despre tuneluri, şi forturi buncăre accessed on 17 February 2010 .

- ^ Siebenbuergen.de, accessed on October 13, 2008 .

- ^ Religion.orf, accessed on October 13, 2008 .

- ↑ Villa of Romania's ex-dictator Ceausescu opens gates at orf.at on March 13, 2016 , accessed on March 13, 2016.

- ↑ J. Vossen. Bucharest - The development of urban space. From the beginning to the present, Berlin, 2004.

- ^ Meyers Konversationslexikon, fourth edition, 1885-1892 .

- ↑ Ghid-Bucaresti.ro of July 21, 2008 .

- ↑ Bucharest Info from July 27, 2008 .

- ↑ Results finale 5th June 2016: Mandate la CGMB (Romanian) . 5th June 2016.

- ↑ USB goes to court for recounting . June 10, 2016.

- ^ Adrian Nicolae Petcu: Piety of the Romanians for Sfântul Dimitrie cel Nou. ziarullumina.ro, October 26, 2010, accessed October 21, 2018 (Romanian).

- ↑ Bucharest homepage from July 21, 2008 ( Memento of the original from March 24, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. .

- ↑ Bethlehem Twinning Cities (English)

- ↑ Birgitta Gabriela Hannover, Discover Bucharest, p. 57, 2008.

- ↑ Bucharest: The urban population and their housing supply, Daniel Kamleitner, Ursula Lehner, Michaela Prammer-Waldhör, Karin Städtner, Michael Wagner-Pinter, Vienna July 2007 (PDF; 87 kB).

- ↑ M.Rute / R.Schediwy in Wiener Zeitung of July 21, 2008 ( Memento of February 7, 2006 in the Internet Archive ).

- ^ Sebastian Bonifaciu, Emanuel Valeriu: Bucharest from A to Z, p. 102.

- ^ Sebastian Bonifaciu, Emanuel Valeriu: Bucharest from A to Z, p. 247.

- ^ Sebastian Bonifaciu, Emanuel Valeriu: Bucharest from A to Z, p. 153.

- ↑ Museum Grigore Antipa (ro) July 21, 2008 ( Memento of 28 April 2010 at the Internet Archive ).

- ^ Sebastian Bonifaciu, Emanuel Valeriu: Bucharest from A to Z, p. 161.

- ^ AT Razvan, Cișmigiu - or dreaming under trees, p. 30, from Merian, Bucharest and Romania's Black Sea Coast, volume 6 / XIX, Hoffmann and Campe (June 1966).

- ↑ Page no longer available , search in web archives: ADZ.ro, November 22, 2008, accessed on November 25, 2008 .

- ^ Theater in Bucharest from July 21, 2008 ( Memento from February 24, 2008 in the Internet Archive ).

- ↑ CEE Musiktheater, National Opera Bucharest from July 21, 2008 ( Memento of the original from January 18, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. .

- ^ Odeon of July 21, 2008 ( Memento of October 30, 2008 in the Internet Archive ).

- ^ Sebastian Bonifaciu, Emanuel Valeriu: Bucharest from A to Z, p. 196.

- ^ Sinziana Pop: Calea Victoriei - die Siegstrasse , p. 11, from Merian, Bucharest and Romania's Black Sea Coast, Issue 6 / XIX, Hoffmann and Campe (June 1966).

- ^ Horst G. Klein, Katja Göring: Romanische Landeskunde, p. 169, Gunter Narr Verlag, 1995, ISBN 3-8233-4149-9 .

- ^ Alan Berube, Jesus Leal Trujillo, Tao Ran, and Joseph Parilla: Global Metro Monitor . In: Brookings . January 22, 2015 ( brookings.edu [accessed July 19, 2018]).

- ^ Sebastian Bonifaciu, Emanuel Valeriu: Bucharest from A to Z, p. 27.

- ^ General German newspaper for Romania from February 27, 2007, accessed on July 27, 2008 ( Memento from October 25, 2008 in the Internet Archive ).

- ↑ Romexpo.org of August 9, 2008 ( Memento of the original of July 27, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. .

- ↑ Mercer's 2018 Quality of Living Rankings. Retrieved July 30, 2018 .

- ↑ Information on the website of the Society for Road Infrastructure (CNAIR) accessed on December 26, 2016 (Romanian).

- ↑ Birgitta Gabriela Hannover, Discover Bucharest, p. 53, 2008.

- ^ Bucharester Verkehr, goruma.de, from July 25, 2008 ( Memento from April 24, 2012 in the Internet Archive ).

- ↑ Parc autobuze RATB (rum.) Of November 10, 2008 ( Memento of November 7, 2011 in the Internet Archive ).

- ^ Report on the opening of the cycle path on Calea Victoriei (Romanian), accessed on August 28, 2015 .