History of Bucharest

The history of the city of Bucharest including the settlement of the urban area around the Colentina and Dâmbovița rivers goes back over 2000 years. Since then the place has developed into today's metropolis and capital of Romania . Bucharest itself was first mentioned in a document in 1459.

The city finally replaced Târgovişte as the residence of the princes of Wallachia in the second half of the 17th century . As a result, despite a series of natural disasters, epidemics and conflagrations, it developed into an important economic center. After the establishment of the Romanian state, Bucharest became its capital in 1862. During the Turkish wars and the First and Second World Wars, Bucharest was repeatedly occupied by foreign troops.

During the term of office of the Romanian dictator Nicolae Ceaușescu , a new phase of urban development began, which was characterized by a radical reconstruction of the city center at the expense of the historic city district. After the Romanian Revolution , urban planning was based on the standards of Western European metropolises.

Beginnings, suburban period

Derivation of the name

Legend has it that Bucharest was founded by a shepherd named Bucur. Bucurie means happy joy in Romanian, therefore Bucur esti means 'you are happy'. Another story tells of the Getenkönig Dromichaetes , who is said to have built the city.

Oldest finds

Archaeological excavations on the banks of the Dâmbovița and Colentina unearthed finds from the Paleolithic , Neolithic and Bronze Ages . Traces of the Paleolithic were discovered on today's Strada Ziduri intre Vii, on Lake Herastrau , in Bucureștii Noi, on the hill of the Radu Vodă Church and the hills next to the Mihai Vodă Church. In Dudeşti, Mihai Vodă and on Lake Tei, remains from the Neolithic were found. The finds from the Bronze Age extend from 1800 BC. Chr. To 700 BC. Chr. Archaeologists explored especially the Glina settlements at Fundeni and Crivăţ.

Since around the 5th century BC The area around what would later become Bucharest was settled by the Getes and Dacians . However, urban development did not begin either under them or in Roman and Byzantine times. Despite some finds from Roman times at Lake Tei and in the Giuleşti district , a Roman military camp in the area of today's Bucharest could not be convincingly proven.

First signs of settlement, ascent to the royal seat

Probably in the second half of the 13th century the development of a settlement in what is now Bucharest began. The political unification of Wallachia under Prince Basarab I (approx. 1310-1352) created the basis for the development of a residential city . However, there are no mentions of Bucharest from the time of Basarab and his successor Nicolae Alexandru. First references to fortifications come from the years 1368 and 1396/97. In several sources a fortress Dîmboviţa is mentioned, which was presumably on the area of the later Bucharest. After 1400 there was evidence of a craftsmen's settlement with a forge, pottery and tannery.

The first written mention of the place comes from September 20, 1459. It was attested by the signature of Vlad Țepeş (his person served as a template for Bram Stoker's Dracula ) .

In the second half of the 15th century Bucharest developed into the Curtea (princely seat) of Wallachia . After Vlad Țepeș, his brother, Prince Radu the Beautiful, also stayed in Bucharest. At that time, there is evidence that 18 documents were drawn up in Bucharest. In a document dated October 14, 1465, Radu designated Bucharest for the first time as the seat of a prince. In a letter to Pope Sixtus IV thirteen years later, the Hungarian King Matthias Corvinus rated Bucharest as "the strongest fortress in Wallachia, both artificially and naturally fortified".

After Curtea de Argeş , Bucharest was alternately with Târgovişte the capital of the Principality of Wallachia until 1659 . The city gained its importance as a princely center of power and trade, which was located in a conurbation of settlements. Between 1459 and 1625 41 settlements emerged in what is now Bucharest. The main market arose around Lipscani Street.

Phase of Ottoman tribute rule (late 14th-17th century)

The Ottoman Empire expanded into Europe from the middle of the 14th century, an expansion that also affected Wallachia. In 1394 a first Ottoman army advanced across the Danube . As a result, the Principality of Wallachia was first subject to tribute. The expansion of the Ottoman Empire was interrupted in 1402 by the defeat in the Battle of Ankara . Soon after, however, in 1414 and 1417, Mehmed I was able to enforce a new tribute agreement with Wallachia.

Bucharest benefited economically from the presence of the court and the return of foreign traders. The population increased, so did the number of buildings, and an urban structure developed. In the second half of the 15th century the mint was moved to Bucharest. With the rule of Mircea Ciobanul , a period of eventful changes began for the city. In 1545 Prince Mircea Ciobanul built the first city wall in the form of a palisade wall and donated the Old Court Church Curtea Veche , which is still preserved today . A large part of the arable and pasture land surrounding the city has now been marked with boundary stones as “the land of the city citizens” (moșia orășenilor) . After the prince was deposed in 1554, the Turks looted and pillaged the city and murdered its dignitaries. When Ciobanul came to power again in 1558, he took revenge on the city's representatives. On the occasion of a banquet in February of that year he had many boyars, prelates and abbots killed. Despite these strokes of fate, the economy and the population grew in the following years.

A limited independence of the citizens showed in the fact that the city had a council. A document dated May 13, 1563 mentions a prefecture and 12 parish councils that were at the head of the city. The city took on supply functions for the surrounding area and among other things became an important grain transshipment point for long-distance trade, especially with the Ottoman Empire.

The rigid Ottoman tribute system put a strain on the city's economic development. In 1574 and 1575 and 1594, the urban population rose against the growing tributes of the Sublime Porte . She also took part in the battles of Mihai Viteazul (Michael the Brave) against the Ottoman army . {In this context, Grand Vizier Koca Sinan Pasha conquered the city in August 1595 after the battle of Călugăreni . A city fire broke out. In the autumn of next year there was unexpectedly another attack by the Tatars near Bucharest, in which the Turks withdrew. Part of the city was again put in ashes. For this reason, the prince's seat was then moved to Târgovişte until 1626. Urban reconstruction began during this period. Radu Șerban (1602–1611) had the first bridge built over the Dâmboviţa and Prince Alexandru Coconul finally moved the residence back to Bucharest shortly after taking power on November 10, 1626 .

After Prince Matei Basarab was the last of the predominant Wallachian family to take the throne in 1632, he built numerous buildings in Bucharest. Because of his tense relationship with the Ottomans, the prince moved to Târgovişte around 1640. Meanwhile, the princely seat remained in Bucharest. Towards the end of the first half of the 17th century, a document proves the attempt by the central authority to curb the expansion of the city by marking the city limits with stone crosses, whereby it was forbidden to build new buildings beyond this boundary. In fact, this measure did not restrict further growth. Basarab's successor, Prince Constantin Șerban , moved to Bucharest again after taking office in May 1654. The following year, the Dorobantzen and infantrymen revolted against the boyars at the headquarters of today's National Bank . On the occasion of the riots, Prince Șerban had the royal court and the city set on fire when he withdrew to Târgovişte and moved the princely seat. The riots continued under Prince Mihnea III. away. When the prince rebels against the Turks, he is defeated by them and Bucharest is plundered.

Final capital (from 1659)

After his enthronement, Prince Gheorghe Ghica relocated the princely seat to Bucharest on December 20, 1659. In the same year, under pressure from the Ottoman Empire, the city became the sole residence of the voivodes ; from now on it remained the final capital of Wallachia. This is followed by five decades of peaceful and stable urban development. During this period, the city's population grew to around 60,000. These were spread over 21 districts (so-called mahalale ) and there were around 100 churches. During Radu Leon's term of office , the church on the Metropolitan Hill was renovated and, according to a resolution documented on July 8, 1668, the religious leadership of Orthodoxy was moved to the capital. During the reigns of Șerban I. Cantacuzino and Constantin Brâncoveanu , Bucharest flourished for a long time. The city became a great commercial and cultural center. On the orders of the princes, the first hospitals, printing works, educational institutions, other churches, the Mogoșoaia Castle and the grand and arterial road Podul Mogoșoaia were built. The craftsmen and merchants were organized in guilds or fraternities. There were goods from many countries. The power-hungry Prince Brâncoveanu abolished the office of mayor and the city council during this time and reserved the exclusive right of government.

Phanariot period (1716-1821)

After the Ottomans had lost their supremacy over Transylvania as a result of the Peace of Karlowitz , they introduced the Phanariot rule in Wallachia and previously in Moldova in 1716 . Members of important Greek families from the Phanar district in Istanbul were appointed as princes. During their reign, the burden on the population through taxes and tributes, but also through nepotism and corruption, increased so much that this phase is still considered the epitome of exploitation, corruption and mismanagement in Romania. During this period there was also progress in urban development.

During the reign of Ioan Mavrocordat , a fire destroyed parts of the city in February 1718. In the same year there was a famine due to a lengthy drought. This was followed by the plague, of which Prince Nicolae Mavrocordat also died on September 3, 1730 . Eight years later, on May 31, a strong earthquake shook the capital. This is followed by a renewed outbreak of the plague and a large plague of locusts . The Greek chronicler Constantin Dapontes claims that ten thousand people died in Bucharest as a result from July to October 1, 1738. In 1753, due to the unbearable tax burden on the intervention of the Bucharest people, Prince Matei Ghica was ousted by the High Porte . Twelve years later, Stephen Racoviţă met the same fate in the revolt of the guilds . The prince defeated the rebels, but was deposed by the Sublime Porte because of the reprisals he had imposed.

In the Russo-Turkish War (1768–1774) , the Russian Field Marshal Nikolai Wassiljewitsch Repnin was given command of all of Wallachia. He triumphed on October 30, 1771 at Bucharest over the Turks, who consequently had to evacuate Moldavia and Wallachia and only got them back through the Peace of Küçük Kaynarca (1774).

After the peace, Constantinople's influence on everyday life in the city increased. The members of the royal family Ypsilantis did a lot for Bucharest. During the reign of Alexander Ypsilantis in particular , many city improvements were made and the first aqueduct was built (1779). Because of the frequent flooding of the Dâmbovița, the prince also had a diversion canal built. Furthermore, the area around the city was delimited again and the number of neighborhoods was limited to sixty-seven. At the same time, the first industrial development began in the city through factories . In 1764 a wax factory was established, one for clothes in 1766, and one for paper in 1767.

During the Russo-Austrian Turkish War from 1787 to 1792, this development was briefly interrupted when Prince Nicolae Mavrogheni fled the city on October 26, 1789, accompanied by an army of around a thousand men. The city was captured by the Austrians two weeks later - on November 10th, 1789 - and only given back in the peace of August 4th, 1791. In 1798, one counted 6006 houses and 80 suburbs. The first work began in the same year in Cișmigiu Park , the oldest park in Bucharest. In 1801 there was a pogrom in the city , which killed 128 Jewish residents.

Towards the end of the 18th century, Pasha Osman Pazvantoğlu von Widin undertook numerous raids into Wallachia, which was under Ottoman suzerainty. In 1802, the news that Pazvantoğlu was approaching Bucharest prompted many merchants and clergy to flee to Transylvania. The area around Kronstadt alone housed 6,000 refugees, including Prince Mihai Șutu . In the following year, the newly appointed Prince Konstantin Ypsilantis was able to prevent Turkish troops from entering Bucharest with 3500 soldiers. In the meantime, two earthquakes (1793 and October 26, 1802), waves of plague (1794 and 1813), floods (1805 and 1806) and a conflagration (1804) ravaged the city. Many people lost their lives, especially during the plague epidemics.

Between Russia and the Ottoman Empire (1807–1861), capital

In 1807, Bucharest came under Russian command during the Russo-Turkish War . The Peace of Bucharest ended the war on May 28, 1812 after six years. Towards the end of the war, Kalmuck troops looted the capital, mainly destroying the Jewish quarter and killing numerous Jewish residents.

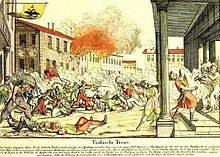

During the Greek uprising of 1821, the Wallachian leader Tudor Vladimirescu stayed in Bucharest from March to May. Tudor camped with his troops on 19/31. March at Cotroceni. Three days earlier he had issued a proclamation calling on the people of Bucharest to resist. Around a thousand tanners and workers from the Radu-Vodă district and the neighboring districts answered the call. Subsequently, there is a break with the entire feudal system. This led to retaliation by the Turkish troops who subsequently occupied Bucharest and captured and executed the commander. These reprisals only ended with the withdrawal of the army in September 1822 and the accession of the local Prince Grigore IV Ghica to the throne . However, the Ottoman occupation continued to generate significant costs. As a result, taxes had to be tripled in some cases. Despite these stresses, the wooden bridges in the city were repaired, the road to the outer market paved and the lighting improved.

Period of the Organic Regulations

During the Russo-Turkish War of 1828–1829 , the Russian Field Marshal Count zu Sayn-Wittgenstein conquered the city. After the Treaty of Adrianople , Bucharest came under Russian protection. From that year until 1834 General Pavel Kisseljow administered the city. During his tenure, the unpopular decree of the Organic Regulations (Règlement organique) was introduced and a committee was set up to beautify the city. According to the statute for the city beautification, the city limits were redefined. In the northeast the Pantelimon monastery and in the south the hills Spirei and Filaret as well as the then Bellu garden were included in the urban area. The northern border ended at the Piața Victoriei. This continued the improvements that had begun on September 30, 1825 with the completion of the first "paved streets of the outer city". Further urban development measures, such as the creation of promenades and marketplaces, were carried out. In 1831 a new municipal leadership was elected. In addition, an infantry regiment, a cavalry squadron and an artillery regiment were stationed in the city. The first maneuver took place in the fall of 1831.

The organic regulations led to urban progress in the areas of administrative organization, freedom of trade and the separation of powers. In contrast, the situation of the peasants deteriorated because of their duties and rights. Due to the repeated influence of Russia, the regulations were viewed more and more critically in the following years. A year before the Wallachian Revolution, on March 23, 1847, a great fire destroyed many buildings in the commercial part of the city. 1,850 buildings of which 1,142 shops and 12 churches and monasteries were severely damaged. The event triggered a supra-regional relief effort. A planned reconstruction then followed.

Wallachian Revolution, Union of Danube Principalities

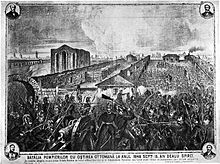

The following year Bucharest was the center of the Wallachian Revolution . The movement began in several places around the country. But it was primarily a revolution of the Bucharest because it was prepared in the city and supported primarily by supporters of the Bucharest population. The center for mass gatherings was the so-called Filaretfeld (freedom field). With the beginning of the revolution, the organic regulations were declared ineffective by the insurgents. This survey, which began on June 11, 1848 in Bucharest, was suppressed three months later, on the evening of September 13, on Spirei Mountain. At the request of Russia, Ottoman troops occupied the city and thus ended the uprising. A memorial at this point commemorates the event.

Bucharest then remained under a double occupation for a long time. The last troops left the city in April 1851. Between 1853 and 1856 - during the Crimean War - Bucharest was successively occupied by Russian, Turkish and Austrian troops. Prince Barbu Dimitrie Știrbey therefore left the throne shortly after the entry of the Russian army in October 1853 and went to Vienna. A year later, after the arrival of the Austrians, the prince returned to Bucharest under Feldzeugmeister Johann Baptist Coronini-Cronberg . In the second term of office of the prince on March 10, 1855 the telegraph line Bucharest - Giurgiu was opened. As the first Romanian city and one of the first cities in the world, Bucharest introduced kerosene lamps to street lighting in May 1857 .

In the previous year, the “Diwan Ad-hoc Assemblies” (joint representative body) met in parallel in Iasi and Bucharest with the aim of uniting the two Danube Principalities of Moldova and Wallachia. The decisive assembly in Bucharest passed a resolution on October 9, 1857. It provided that the two principalities would each be led by their own regent and their own government. Laws, administration, currency and taxes should, however, be standardized by a joint commission. At the beginning of 1859, the legislative assemblies of Wallachia and Moldova each elected Colonel Alexandru Ioan Cuza as prince and thereby established a personal union that would later lead to the Real Union. When choosing the new capital city location, after some discussion, the decision was almost unanimously in favor of Bucharest. Because of this, between 1859 and 1861 some joint institutions, such as the War Ministry and the Customs Office, moved their central headquarters to the capital.

Capital of Romania, industrialization up to the First World War (1861–1916)

On December 24th, 1861, Cuza proclaimed the formation of the Principality of Romania from the Danube Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia. A year later, the two principalities were also formally united with Bucharest as the capital. In June of the same year, however, Prime Minister Barbu Catargiu was murdered in the car of the police prefect in Bucharest. The background to the fact remains unclear to this day.

The founder of the state, Alexandru Ioan Cuza, later came under fire and had to abdicate in 1866. In the same year, a provisional government appointed Karl Eitel Friedrich von Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen as prince. After being elected prince, he moved into Bucharest as Carol I on May 10, 1866. On July 11th, the convened Constituent Assembly voted for a new constitution, which remained in force until 1923.

At that time, Bucharest was one of the centers of Bulgarian exile. In 1853 the Bulgarian Charity Organization (Bulgarian Добродетелна дружина) was founded here. In the years 1868 and 1869, several Bulgarian organizations were established which organized and financially supported the armed struggle of the Bulgarians who were still under Ottoman rule, including the Bulgarian Society (Bulgarian Българско общество), the Young Bulgaria Group (Bulgarian Млада България) and das Bulgarian Revolutionary Central Committee ( BRZK ), which later became the head of the “ Inner Revolutionary Organization ” (IRO).

The lively cultural and scientific life continued in the city. The National Theater, the Romanian Academy , music halls and cultural associations were created. In addition, the botanical garden "Dimitrie Brândză" and large cemeteries were created and medical institutes were founded. In 1869 the capital was equipped with a first railway line . It connected Bucharest with Giurgiu . Two years later the first tram line (a horse-drawn tram) was opened from the Nordbahnhof via Piața St. Georg to Piața Obor. After four years of construction, the North Railway Station opened in 1872 , as did rail traffic between Bucharest and Ploieşti .

After the Berlin Congress in 1878, Romania was recognized as sovereign. In the same year, the temporary triumphal arch was built at the end of Kiseleff Avenue . According to the city's employment statistics, a total of 27,100 merchants, 64,732 industrialists and craftsmen, 11,993 workers, 19,531 servants and 50,977 owners, renters and freelancers were employed in the city at that time.

On March 26, 1881, the principality proclaimed itself the Kingdom of Romania . It was oriented towards the west, especially towards France. During the modernization, Prussia was a supplier of ideas and technology. At that time, construction work on the Dâmbovița Canal had already started. The deepening and regulation work according to a plan by the architect Grigore Cerchez began on November 21, 1880 and lasted until 1883. Work on securing the drinking water supply began immediately afterwards.

The Belgian general Henri Alexis Brialmont received an order from the Romanian government in 1883 to develop a defense system for the country. Brialmont then drew up plans for fortifying the border and fortifying Bucharest. For Bucharest he designed 18 batteries that were to be connected underground. However, the plans were not fully implemented because the Belgian government recalled Brialmont at short notice.

Between 1885 and 1888, the Romanian Athenaeum was built according to the plans of the architect Albert Galleron . In the year of completion, the ultra-conservative opposition opposed Prime Minister Ion C. Brătianu . Oppositionists invaded the royal palace and the parliament in March 1888. There was bloodshed when the summoned military drove the insurgents out. Prime Minister Brătianu resigned in March as a result of the uprisings and street riots, as well as a lack of support.

After the National Industry Protection Act came into force in 1887, new industrial plants were built in the city. By 1893, a total of 102 municipal companies with 7,128 employees had benefited from this law. In 1895 an anti-Semitic alliance ( Alianța Antisemită ) was founded in Bucharest , which several politicians were close to and which advocated further tightening of the measures directed against Jews .

At the end of the 19th century, Bucharest developed into an industrial center, especially in light industry. In 1902, 178 of the 367 industrial plants in the former Wallachia were in Bucharest. Five major banking institutions - including the National Bank , the Bank of Romania, the Agricultural Bank and, since 1898, the Discount Bank - made Bucharest the national financial center. Electric light was introduced on Calea Victoriei in 1890. During this time, the new traffic artery from Ober to Cotroceni was opened. In 1896 the line service of the first electric tram followed on the same route. The same year the first cinema opened on Calea Victoriei. On the occasion of the 40th anniversary of King Carol I's accession to the throne, the Parcul Carol was built between 1900 and 1906 . In 1906 a mosque was built in this park as a symbol of reconciliation after the war of 1877/1878.

In 1907 there was a peasant uprising in Romania . The farmers protested against their living and working conditions as well as the unjust distribution of land. With the start of the marches of looting and destruction, many interim tenants and land managers fled to the cities. Because of this, several thousand farmers moved against Bucharest in March of that year. But they were stopped by soldiers in advance. The new Minister of War and General Alexandru Averescu then suppressed the uprising within a few days through massive military action. The exact number of deaths is not known, the officially stated number of 419 has been far exceeded.

Towards the end of the second Balkan War , envoys from the five warring states met on July 30, 1913 for their first meeting in the building of the Bucharest Foreign Ministry. The twelve meetings ended on July 28th . / August 10, 1913 greg. with the Peace of Bucharest .

First World War

With the outbreak of World War I , Bucharest became the center of a distinct movement for the completion of nation-state unification. On August 27, 1916, Romania entered the war on the side of the Entente . In response to Romania's participation in the war , a German zeppelin attacked Bucharest the next day . Further attacks by airships took place on September 4th, 5th and 24th. On September 25th, pigeon planes also began to attack the capital. Many people were killed and injured in the air strikes. The Romanian army was defeated in December in the Battle of the Argesch . After the German and Austro-Hungarian troops merged shortly before Bucharest, troops of the Central Powers marched into the city on December 6, 1916 . Because of this, Bucharest had to temporarily (until 1918) surrender its capital status to Iași .

In 1917 the Romanian Air Corps went down in Bucharest with the military defeat of Romania. A year later, on May 7, 1918, the peace treaty between Romania and the Central Powers was signed in Bucharest . The city remained under German occupation until November 1918. Due to the material and economic situation, the workers went on strike at the end of 1918. This was on 13./25. December was bloodily crushed by those in power in the National Theater Square and Câmpineanu Street. 102 people were killed.

Enlarged Romania, expansion of the capital

The importance of Bucharest as the capital of Greater Romania grew after the First World War with the amalgamation of the "Old Reich" with Transylvania , the Banat and Kreisch area , Bukovina and Bessarabia . From 1918 to the beginning of the Second World War, the urban area increased by 5600 to 7800 hectares . The number of inhabitants rose from 380,000 to 870,000 in the same period. The economy developed differently in the interwar period. During this time Bucharest gradually became an industrial city. As a result of the global economic crisis , Bucharest also found itself in a downward spiral. After the crisis, trade increased again significantly by 1939.

In October 1920 a general workers' strike took place in the center of the city. A year later the Congress of the Socialist Party met in Bucharest. The Romanian Communist Party was founded . Ferdinand I died on July 20, 1927. The five-year-old grandson Michael I then formally ascended the Romanian throne for the first time for three years because Ferdinand's son Karl was not considered a suitable heir to the throne because of an affair with the divorced Jewess Magda-Elena Lupescuals.

According to plans by Nicolae Nenciulescu, the Bucharest Royal Palace (today the Muzeul Național de Artă al României ) was built in the neo-classical style from 1927 to 1937 . King Michael I lived in the castle until his abdication. After returning from exile on June 6, 1930 and promising to part with Magda-Elena Lupescu, Carol II became King of Romania on June 8. Oil workers and railroad workers went on strike from January to February 1933 because of the deterioration in living conditions. During this time there were sharp clashes with the bourgeoisie . The bloody strike suppression on February 16, 1933 at the Grivița works of the state railway company CFR aroused international attention.

King Carol II dismissed the government on February 10, 1938 and set up a royal dictatorship to prevent the formation of a government whose ministers would have belonged to the fascist movement of the Iron Guard . By 1940 the conflict between her and other political groups turned into almost a civil war. After the arrest of Corneliu Zelea Codreanu , this and other legionaries were killed on the night of November 29th to 30th, 1938 near Tâncăbeşti while trying to escape. At the instigation of his successor Horia Sima , members of the Iron Guard committed an assassination attempt on the Romanian Prime Minister Armand Călinescu in Bucharest on September 21, 1939, among other things in revenge for the killing of Codreanu . After the attack was announced on the radio, the perpetrators were caught in the radio building .

With the construction of the axis Piața Victoriei and Piața Sf. Gheorghe between 1936 and 1940 based on the model of Avenue Henri-Martin (Paris) and Avenue Louise , the city was nicknamed Micul Paris ("Little Paris", also "Paris of the East"). There was also a lot of construction in the 1940s, but this time in a modern, international style that was shaped, for example, by Le Corbusier and the principle of form follows function .

On November 10, 1940, a 7.3 magnitude earthquake struck the city. The quake surprised many people while they were sleeping. Around three hundred people died when the Carlton building collapsed. Around 1,000 people died in total.

Bucharest in World War II (1940-1945)

Romania joined the Second World War after initial neutrality on November 23, 1940 the Tripartite Pact between the German Reich , the Japanese Empire and the Kingdom of Italy in. This was the direct result of the formation of the government of a "national legionary state" on September 4, 1940 by the Iron Guard and General Ion Antonescu and led to the abdication of Carol II in favor of his 19-year-old son Michael I. At Antonescu's request, a German Army Mission requested to train Romanian troops. In addition, the Iron Guard tightened anti-Semitic laws. German troops arrived in Romania on October 8, 1940, and shortly afterwards in Bucharest.

Romania took part in the German-Soviet War on June 22, 1941 . As a result, Bucharest was attacked by the Soviet air force the following month . However, there was no major personal injury or property damage. Previously, in January 1941, an attempted coup by the far-right legionaries of the Iron Guard against Antonescu's totalitarian government failed. This coup was connected with a pogrom against the Romanian Jews . 118 Jews lost their lives in Bucharest alone. On the orders of Marshal Antonescu, over 24,000 Roma were deported between June and September 1942 . They came mainly from Bucharest and the surrounding villages and cities and were forcibly deported to Transnistria .

In early April 1944, Bucharest came within range of the American and British air forces. The first major attack took place on April 4, 1944 by the 15th US Air Force . A total of 875 tons of bombs were dropped. The main train station (Gara de Nord) was also bombed. This was intended to interrupt military transports to the Eastern Front. Because of the strong winds, some of the bombs were carried to residential areas. The data on the victims vary between 2000 and 5000, with the number of 2942 dead and 2126 injured as the official figure. Another heavy attack by the British Royal Air Force followed on April 15 , this time with incendiary bombs. The university was also badly damaged. When the defeat became apparent, Michael I and a newly formed National Democratic bloc under Iuliu Maniu and Dinu Brătianu overthrew Marshal Antonescu on August 23, 1944. Adolf Hitler then ordered the bombing of Bucharest that same night, which continued the following night. 182 people were killed. Many government buildings and historical buildings were damaged or destroyed. A day later Romania declared war on Germany. The king then appointed a new government consisting of non-party members, members of the Peasant Party, National Liberals, Social Democrats and Communists and put the 1923 constitution back into force. After the Red Army marched into Bucharest on August 31, there was an armistice on September 12, 1944 between Romania and the Soviet Union.

From the Second World War to the Romanian Revolution (1945–1989)

Before the formation of the Groza government on March 6, 1945, there were some mass rallies. On February 24, 1945, one of the largest demonstrations in the city's history resulted in many arrests and injuries. The interior ministry building was shot at during the rally, killing six protesters. As a result of disputes between the new Prime Minister Petru Groza and King Michael I, the latter refused to sign any laws in 1945, whereupon Groza decided to put the laws into force without a royal signature.

In a public trial, the Bucharest “People's Court” sentenced former Prime Minister Ion Antonescu to death on May 17, 1946. The execution took place on June 1, 1946 in Jilava prison near Bucharest. After the peace treaty of 1947 the way was clear for the Communist Party , the monarchy ended on December 30, 1947. Under pressure from the Communists, King Michael I abdicated and fled to Switzerland. On the same day, the Romanian People's Republic was proclaimed on the Bucharest Square of the palace .

Phase of socialist urban development (1947–1977)

This marked the beginning of the socialist urban development phase for Bucharest. In the four decades after World War II, the city grew to more than double its population. Especially in the peripheral areas it became a huge construction site. The city area tripled in this time to 21,700 hectares. Bucharest particularly attracted farmers to the city, who found work in the large industrial plants here. They brought their rural way of life with them to the metropolis and still determine their image today. In order to be able to meet the strong demand for housing, the government launched an extensive housing construction program.

In 1953 the 4th World Festival "For Peace and Friendship", in which 30,000 young people and students from 111 countries took part, took place in Bucharest. On the occasion of the games, the newly built Lia Manoliu Stadium and the opera and ballet theater were inaugurated at the end of July 1953 . The so-called Bucharest Declaration (“Declaration for the Guarantee of Peace and Security in Europe”) received international attention. It was adopted by the Warsaw Pact after the Bucharest Conference, which took place from July 4 to 6, 1966 .

A year later, began under the code name top secret channel of free purchase of Romanian Germans . At the beginning of 1968, the then federal government appointed the lawyer Heinz Günther Hüsch as negotiator. This led his first round of negotiations from February 9 to 12, 1968 with the representatives of Romania in Bucharest's Ambasador Hotels.

At the end of 1971 there were 235 industrial companies in the city, 175 of them of national importance. Industrial production accounted for 17.3% of national production. Over 39% of the city's production came from the engineering and metalworking industries. In 1972 around 65,000 students studied at the 60 faculties of the 13 university institutes. The urban expansion of Bucharest also led to the incorporation of many surrounding areas. According to the research of the historian Constantin C. Giurescu , a total of sixty-four villages and hamlets were attached to the city between the founding of the city and 1976.

An earthquake whose epicenter was in the Vrancea district shook the area around Bucharest on March 4, 1977 with a magnitude of 7.2 on the Richter scale. Entire rows of houses and many high-rise buildings collapsed like houses of cards. The historic structure was also partially destroyed by the tremors. Over 1,500 people died.

Phase after the earthquake up to the Romanian Revolution (1977–1989)

With the clean-up work, a new phase of urban development began, which was characterized by a radical reconstruction of the inner city. After the earthquake, President Nicolae Ceaușescu saw the possibility of almost completely replacing the traditional urban structure of large inner-city areas with a colossal political and administrative center. In their place came new symbols of a monumental show of power. The core and dominant element is the Parliament Palace , which around 70,000 workers were involved in building. The city also got a subway . The first line opened on November 16, 1979 between Timpuri Noi and Semănătoarea . After a further extension, the traffic went to the Republica underground station in 1981 .

From 1982 onwards, the centrally located old residential areas were demolished against the will of the majority of the population. More than 20% of the inner city were affected. A total of around 5.5 square kilometers and around 40,000 apartments are assumed. Over 20 churches disappeared with the demolition. The homeowners were forcibly expropriated; they received little compensation. According to the Systematisation Act, the building site was then nationalized. Most of the residents then got an apartment in the new collective housing estates on the outskirts of the capital. The majority of the affected population did not agree with this urban planning measure.

In mid-December 1989, the popular uprising against Nicolae Ceaușescu began in Timișoara . The uprising reached Bucharest on December 21, because the Ceaușescu regime ordered a public rally in front of the Central Committee of the Romanian Communist Party to show the support of the population after the riots in Timișoara. However, the demonstration turned into the opposite. Securitate troops, snipers and army units equipped with tanks massacred the indignant crowd within a day. Fires broke out in the former royal palace and in the university library. A day later, Ceaușescu tried to speak one last time to the people gathered in front of the building from a balcony of the huge complex on which the Central Committee building was then located. However, shortly afterwards the Ceaușescus had to flee from the roof of the building by helicopter. On the same day, the state television broadcaster TVR announced Romania as exempt. In Bucharest alone there were around 500 deaths.

Post-communist era to the present (since 1989)

After the uprising it turned out that there were bunker systems and tunnels in Bucharest, some of them from the Middle Ages. An escape tunnel led from the former Central Committee building from the Calea Victorei zone to the Universitate underground station. In addition, the Parliament Palace had a large bunker with various exits.

Dissatisfied with the continued political and economic influence of former supporters of the Ceaușescu dictatorship, anti-communist demonstrators met in the same year on Bucharest University Square for an ongoing protest . The demonstrations were also directed against the election of Ion Iliescu as president. In this context, miners from the Shilt Valley ( Valea Jiului ) were brought to Bucharest to break up the demonstrations by force. There were dead and injured in the so-called six “ Mineriades ”. In late September 1991, the Roman government collapsed when the miners returned to Bucharest to demand higher wages and better living conditions.

The representatives of all six Black Sea countries met on April 21 and 22, 1992 in the city. After the conference, the Bucharest Convention (or the Convention on the Protection of the Black Sea from Pollution ) was adopted. The framework convention came into force in 1994. In the same year Bucharest became the permanent seat of the SECI (Southeast European Cooperative Initiative).

After the fall of 1989, another building boom began. In the interest of reorganizing the city center, ideas were created at the end of the 1990s through the urban planning competition "București 2000", which was to form the basis for further urban development. Binding decisions based on the competition result are still pending despite an existing development strategy. The self-indulgence of construction investors later led to protests. According to the protesters, despite an existing master plan, in which 98 zones had architectural protection status, there was no orderly urban development. In 2009, therefore, over 6,000 citizens demonstrated against the urban sprawl.

Despite visible improvements in the living conditions of its population, at times over 3000 Romanian street children lived in Bucharest without any medical care or social security worth mentioning. The problem was known before the Romanian Revolution. However, it was withheld from the public in all its dimensions by the state organs. The city also has problems with a large number of stray dogs. The responsible agencies have therefore taken several tough measures in the past to contain the stray population. This led to many protests and rallies by animal welfare organizations. - Stray dogs are a decades-old problem in Bucharest. Dog lovers feed the stray animals, although they have recently risked heavy fines. In 2012 16,000 people were bitten, in 2006, 2011 and 2013 a total of 3 people were killed in this way.

On his 86th trip abroad from May 7 to May 9, 1999, Pope John Paul II visited a predominantly Orthodox country in Southeast Europe for the first time. At the celebration of the reconciliation between the Orthodox and the Catholic Church in the Romanian capital, the Pope presented Patriarch Teoctist I with a notable donation for the construction of the largest Orthodox cathedral in Romania at the Bucharest Piața Unirii in front of over 60,000 believers.

Even after the turn of the millennium, Bucharest was repeatedly in the focus of the global public. The ninth meeting of the OSCE Ministerial Council took place from December 3-4, 2001 in Bucharest. Influenced by the 9/11 terrorist attacks, the Council adopted a declaration and thirteen resolutions, as well as the Bucharest Plan of Action to Combat Terrorism. Three years later the 23rd Universal Postal Congress and in 2006 the 11th Summit of the International Organization of Francophonie took place in Bucharest .

At the turn of 2006/2007 tens of thousands of Romanians celebrated Romania's accession to the European Union. The then acting EU Council President and Federal Foreign Minister Frank-Walter Steinmeier also took part in the official celebration in Bucharest. In the year Romanian acceded to the EU, there were around 740,000 households in the capital. Around 25% of this was in single-person households. Of the total of 115,000 residential buildings, around three quarters were single-family houses and around 12% were apartment blocks. In the same year, the fifth Patriarch Teoctist I died. Four days after his death, on August 3, 2007, he was buried in the Patriarchal Church. The following year, from April 2nd to April 4th, the city hosted the XX. NATO summit . The summit was dominated by enlargement to the east and with around 3,000 official delegates and the same number of journalists it was the largest NATO meeting in history. In the discussion rounds, the NATO members agreed on an accession procedure for the Balkan states of Croatia and Albania.

Even before joining the EU in 2007, the main priority was to expand the roads and underground lines . The urban development plan also provides for investments in order to develop the neglected districts more quickly. The Arena Națională , which was completed in August 2011 , also replaces the Lia Manoliu Stadium, which was demolished in 2008 . A new town project, the Colosseum Commercial Center with over 480 shops and the Esplanada City Center are in the planning stage.

A fire disaster occurred in Bucharest at the end of October 2015 . In Strada Tăbăcarilor 7, 64 people were killed and 147 injured, some seriously. The government then ordered a three-day state mourning. On November 4, Prime Minister Ponta announced his resignation as well as that of his cabinet after massive popular protests against the government in connection with the fire the previous evening.

See also

- List of Mayors of Bucharest

- List of sons and daughters of the city of Bucharest

- List of rulers of Wallachia

literature

- Florian Georgescu: Bucharest - historical overview , meridians, 1965

- Sebastian Bonifaciu, Emanuel Valeriu (scientific subject area: Șerban Cioculescu, Grigore Ionescu): Bucharest from A to Z, stages and moments of the city's history, pp. 11–30, Verlag für Tourismus, Bucharest 1974.

- Constantin C. Giurescu , (German translation, N. Hochscheidt): History of the city of Bucharest. Sports and tourism publisher, Bucharest 1976.

- Dan Berindei : Bucharest - capital of the Romanian nation. In: Harald Heppner (Ed.): Capitals in Southeast Europe. History, function, national symbolism. Böhlau, Vienna 1994, ISBN 3-205-98255-X , pp. 37-53.

- Paul Jeute: The Palace of the Parliament in Bucharest. Munich, 2011, ISBN 978-3-640-95418-6

- Horst G. Klein, Katja Göring: Romanian cultural studies. Gunter Narr Verlag, Tübingen 1995, ISBN 3-8233-4149-9 .

- Joachim Vossen: Bucharest. The development of urban space. From the beginning to the present. Reimer Verlag, Berlin 2004, ISBN 3-496-02753-3 .

- Birgitta Gabriela Hannover: Discover Bucharest. The Romanian capital and its surroundings - history of the city of Bucharest , pp. 39–51, Trescher Verlag, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-89794-120-5 .

- * Paul Jeute: Bucharest. Myths, destruction, reconstruction. An architectural history of the city. Bonn, 2013, ISBN 978-3-944529-17-2

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Österreichisches Ost- und Südosteuropa-Institut, Arbeitsgemeinschaft Ost (Ed.): Österreichische Osthefte, Volume 37, Issues 1–2, p. 301, from Axel Barner, Bucharest, 1999 Google Books , accessed on December 5, 2010.

- ↑ Hariton Tiktin: Romanian-German Dictionary , Volume I, 3rd edition, Wiesbaden 2001, p. 329.

- ^ Romanian Information Center in Brussels (ed.): Guide to Bucharest - Capital of Contrasts, p. 1 (PDF) ( Memento of November 13, 2011 in the Internet Archive ), accessed on December 18, 2010.

- ^ Dan Berindei: Bucharest - Capital of the Romanian Nation , p. 37, in Harald Heppner (Ed.): Capitals in Southeast Europe - History, Function, National Symbolism , ISBN 3-205-98255-X .

- ^ Constantin C. Giurescu: History of the city of Bucharest. P. 11.

- ^ Constantin C. Giurescu: History of the city of Bucharest. P. 12.

- ↑ Cristian Schuster: On the early Bronze Age settlements and burials in southern Romania , Institutul de arheologie "Vasile Pârvan", Centrul de tracologie, Bucureşti , accessed on February 21, 2011.

- ↑ So presumed Joachim Vossen: Article - Bucharest (City), University of Klagenfurt ( Memento of February 13, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) accessed on December 18, 2010.

- ^ Constantin C. Giurescu: History of the city of Bucharest. P. 21.

- ↑ Edgar Hösch. Karl Nehring, Holm Sundhaussen (Ed.): Lexicon for the history of Southeast Europe , Böhlau, Vienna 2004, ISBN 3-8385-8270-5 , p. 135.

- ↑ Harald Heppner: Capitals in Southeast Europe: History, Function, National Symbolism , Böhlau 1994, p. 37.

- ^ Constantin C. Giurescu: History of the city of Bucharest. P. 24.

- ↑ a b c Sebastian Bonifaciu, Emanuel Valeriu: Bucharest from A to Z - stages and moments in the city's history. P. 13, Pontica Handbooks, Tourism Publishing House, Bucharest (1974).

- ^ Constantin C. Giurescu: History of the city of Bucharest. P. 25.

- ^ Klaus Kreiser: The Ottoman State 1300–1922 , Oldenbourg, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-486-53711-3 , p. 21.

- ↑ Biographical Lexicon for the History of Southeast Europe , Oldenbourg, Munich 1979, Vol. 3, p. 222.

- ^ Joachim Vossen: Bucharest - The development of urban space. From the beginning to the present , Berlin: Dietrich-Reimer-Verlag ISBN 3-496-02753-3 .

- ↑ Constantin C. Giurescu: History of the City of Bucharest , p. 27.

- ^ Constantin C. Giurescu: History of the City of Bucharest , p. 29.

- ^ Dan Berindei: Bucharest - Capital of the Romanian Nation , p. 38 in Harald Heppner (Ed.), Capitals in Southeast Europe - History, Function, National Symbolism, ISBN 3-205-98255-X .

- ↑ Sebastian Bonifaciu, Emanuel Valeriu: Bucharest from A to Z - stages and moments in the city's history. P. 15.

- ^ Constantin C. Giurescu: History of the city of Bucharest. P. 31.

- ^ Constantin C. Giurescu: History of the city of Bucharest. P. 33.

- ↑ Joachim Vossen conjectures : Article - Bucharest (City), Uni Klagenfurt ( Memento from February 13, 2009 in the Internet Archive ), accessed on December 18, 2010.

- ^ Constantin C. Giurescu: History of the city of Bucharest. P. 35.

- ↑ Birgitta Gabriela Hannover, Discover Bucharest - History of the City of Bucharest. P. 42, 2008.

- ^ Constantin C. Giurescu: History of the city of Bucharest. P. 38.

- ^ Dan Berindei: Bucharest - Capital of the Romanian Nation, p. 38 in Harald Heppner: Capitals in Southeast Europe - History, Function, National Symbolism, Boehlau, Vienna 1994, ISBN 3-205-98255-X .

- ^ Constantin C. Giurescu: History of the city of Bucharest. P. 39.

- ^ Constantin C. Giurescu: History of the city of Bucharest. P. 40.

- ↑ Sebastian Bonifaciu, Emanuel Valeriu: Bucharest from A to Z - stages and moments in the city's history. P. 16.

- ^ Constantin C. Giurescu: History of the city of Bucharest. P. 41.

- ↑ Sebastian Bonifaciu, Emanuel Valeriu: Bucharest from A to Z - stages and moments in the city's history. P. 17.

- ↑ Ion C. Butnaru: The Silent Holocaust: Romania and Its Jews. New York et al. a .: Greenwood Press 1992, p. 10.

- ^ Konstantin Jireček: History of the Bulgarians. P. 497, Textor, 2008, ISBN 3-938402-11-3 .

- ^ Karl Ernst Adolf von Hoff: Chronicle of the earthquakes and volcanic eruptions. Volume 2, p. 132, Gotha, 1841.

- ^ Johann Friedrich Reinhold Grohmann: Observations about the plague that ruled in 1813 in Bucharest. Schaumburg, Vienna, 1816.

- ^ Bernard Lazare: The Jews in Romania. Verlag HS Hermann, Berlin 1902. p. 8.

- ^ Constantin C. Giurescu: History of the city of Bucharest. P. 46.

- ^ Constantin C. Giurescu: History of the city of Bucharest. P. 47.

- ↑ Constantin C. Giurescu: History of the City of Bucharest , p. 50.

- ↑ Birgitta Gabriela Hannover, Discover Bucharest - History of the City of Bucharest. 2008, p. 44.

- ^ Constantin C. Giurescu: History of the city of Bucharest. P. 51.

- ↑ Sebastian Bonifaciu, Emanuel Valeriu: Bucharest from A to Z - stages and moments in the city's history. P. 18.

- ^ Constantin C. Giurescu: History of the City of Bucharest , p. 54.

- ^ Constantin C. Giurescu: History of the city of Bucharest. P.56.

- ^ Constantin C. Giurescu: History of the city of Bucharest. P. 58.

- ^ Constantin C. Giurescu: History of the city of Bucharest. P. 61.

- ^ Constantin C. Giurescu: History of the city of Bucharest. P. 62.

- ↑ Sebastian Bonifaciu, Emanuel Valeriu: Bucharest from A to Z - stages and moments in the city's history. P. 22.

- ^ Constantin C. Giurescu: History of the city of Bucharest. P. 63.

- ↑ a b Homepage University of Klagenfurt, Meinolf Arens, Lisa Mayerhofer, Agnieszka Barszczewska: Article Romania (Country) ( Memento from February 13, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) accessed on December 19, 2010.

- ^ Dan Berindei: Bucharest - Capital of the Romanian Nation, p. 46, in Harald Heppner: Capitals in Southeast Europe - History, Function, National Symbolism, Boehlau, Vienna 1994, ISBN 3-205-98255-X .

- ^ Constantin C. Giurescu: History of the city of Bucharest. P. 66.

- ^ Constantin C. Giurescu: History of the city of Bucharest. P. 69.

- ^ Südost-Institut Munich, German Institute for International Studies in Berlin: Southeast Research: International Journal for History, Culture and Regional Studies of Southeast Europe, Oldenbourg, 1952, p. 387 (Google Books), accessed on December 3, 2010 .

- ↑ Birgitta Gabriela Hannover, Discover Bucharest, p. 46, 2008.

- ↑ Sebastian Bonifaciu, Emanuel Valeriu: Bucharest from A to Z - stages and moments in the city's history. P. 23.

- ↑ a b c d Sebastian Bonifaciu, Emanuel Valeriu: Bucharest from A to Z - stages and moments in the city's history. P. 24.

- ^ Dan Berindei: Bucharest - Capital of the Romanian Nation, p. 49 in Harald Heppner: Capitals in Southeast Europe - History, Function, National Symbolism, Boehlau, Vienna 1994, ISBN 3-205-98255-X .

- ^ Constantin C. Giurescu: History of the city of Bucharest. P. 75.

- ↑ Page no longer available , search in web archives: Fortress Study Group, Bucharest and sereth line defense .

- ↑ Home Surprising-romania, Bucharest system of fortifications , accessed on 26 January 2011th

- ↑ German weekly: Collected essays on cultural and contemporary history 1887–1901, Die Woche, 22. – 28. March 1888, Rudolf Steiner's estate, online version , accessed February 6, 2011.

- ^ Constantin C. Giurescu: History of the city of Bucharest. P. 80.

- ↑ Edgar Hösch, Karl Nehring, Holm Sundhaussen, Konrad Clewing (eds.): Lexikon zur Geschichte Südosteuropas , p. 47, Utb, 2004, ISBN 3-8252-8270-8 .

- ^ Dan Berindei: Bucharest - Capital of the Romanian Nation, p. 50 in Harald Heppner: Capitals in Southeast Europe - History, Function, National Symbolism, Boehlau, Vienna 1994, ISBN 3-205-98255-X .

- ^ Image of the mosque in Parcul Carol at show.ro ( memento from August 26, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) accessed on December 17, 2010.

- ^ Wiener Zeitung, Franz Schausberger : Unrest in the Balkans , print edition from Saturday, March 17, 2007 Online version ( Memento from September 30, 2007 in the Internet Archive ), accessed on February 6, 2011.

- ^ Katrin Boeckh: From the Balkan Wars to the First World War - The negotiations of Bucharest , p. 61, Oldenbourg, 1996, ISBN 3-486-56173-1 .

- ^ Constantin C. Giurescu: History of the city of Bucharest. P. 84.

- ^ Gerhard Hirschfeld (ed.), Rudolf Jerabek: Encyclopedia First World War - Bucharest , p. 399, UTB, 2009, ISBN 3-8252-8396-8 .

- ^ Constantin C. Giurescu: History of the city of Bucharest. P. 87.

- ↑ Birgitta Gabriela Hannover, Discover Bucharest, 2008, p. 48.

- ^ Constantin C. Giurescu: History of the city of Bucharest. P. 91.

- ↑ Sebastian Bonifaciu, Emanuel Valeriu: Bucharest from A to Z - stages and moments in the city's history. P. 25.

- ^ Constantin C. Giurescu : History of the city of Bucharest. P. 98.

- ^ Constantin C. Giurescu: History of the city of Bucharest. P. 102.

- ↑ see also en: Avenue Louise

- ↑ Deutsche Geophysikalische Gesellschaft , F. Wenzel: Reduction of earthquake damage - a challenge for geo- and engineering sciences ( Memento of the original from December 21, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Retrieved December 18, 2010.

- ^ Constantin C. Giurescu: History of the City of Bucharest , p. 104.

- ^ You Tube, Video - Earthquake in Romania (November 10, 1940) , accessed December 18, 2010.

- ^ Institute for Contemporary History Munich: Quarterly Issues for Contemporary History, 3rd issue, July 1966 (PDF; 6.1 MB) accessed on October 30, 2010.

- ^ Constantin C. Giurescu: History of the city of Bucharest. P. 105.

- ↑ Christina von Braun , Eva-Maria Ziege (Ed.): The movable prejudice - aspects of international anti-Semitism , The deportation of the Roma and other expulsion plans, p. 183, Koenigshausen + Neumann, 2005, ISBN 3-8260-2820-1 .

- ↑ Donald Kenrick: Sinti and Roma - The Destruction of a People in the Nazi State , p. 95, Society for Threatened Peoples, 1981.

-

↑ a) Homepage Scribd.com, Narcis Ionuţ Gherghina: Istoria Bombardamentelor Americare, 1943-44, page 43 , ISBN 973-615-005-4 , accessed on December 5, 2010,

b) Homepage Etd.ceu.hu, Sorin Marin : The Social Consequences of the 1944, Anglo American Bombing of Ploiesti, Budapest, 2008 (PDF; 2.3 MB) accessed on December 5, 2010,

c) Homepage History-cluj.ro, Ottmar Traşcă: Bombardamentele anglo – americane asupra României , April – August 1944. Percepţii germane şi maghiare. În “Anuarul Institutului de Istorie Cluj-Napoca”, Cluj-Napoca, 2002, 41, p. 191–209, Institutul de Istorie “George Bariţ” (PDF) accessed on December 5, 2010,

d) Homepage Jurnalul.ro, Daniela Cârlea Şontică: Anglo-American bomb of July 3, 2006, accessed on December 5, 2010. - ^ Constantin C. Giurescu: Istoria Bucureştilor. Din cele mai vechi timpuri pînă în zilele noastre ('History of Bucharest. From the early days to the present day'), Ed. Pentru Literatură, Bucharest, 1966.

- ↑ Commons Iuliu Maniu and IC Bratianu 1942 memorium by Ion Antonescu from Andreea Dobeş, Iuliu Maniu - Un creator de istorie, Fundaţia Academia Civică, Bucharest, 2008. ISBN 973-8214-18-6 or ISBN 978-973-8214-11- 8 .

- ↑ Homepage Aviatori.ro, Gherghina, I., Narcis, Capitala României sub bombele germane (23-26 August 1944), In Dosarele Istoriei. No. 8 (97), 2004, p. 35-38 , accessed December 18, 2010.

- ^ Homepage University of Klagenfurt, Ralf T. Göllner: Article Romania (Land) ( Memento from February 13, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) accessed on December 19, 2010.

- ^ Constantin C. Giurescu: History of the city of Bucharest. P. 111.

- ^ Constantin C. Giurescu: History of the city of Bucharest. P. 112.

- ↑ Homepage Weltfestspiele.de, History of the World Festival ( Memento of the original from December 9, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Retrieved December 18, 2010.

- ^ Constantin C. Giurescu: History of the city of Bucharest. P. 123.

- ↑ Homepage Federal Agency for Civic Education, Manfred Görtemaker: From the Cold War to the era of détente , information on political education (issue 245) , accessed on December 18, 2010.

- ↑ Homepage Siebenbürgische Zeitung, Buying Romanian Germans Free in the Years of Communism, May 3, 2010 , accessed on December 20, 2010.

- ^ Sebastian Bonifaciu, Emanuel Valeriu: Bucharest from A to Z. p. 27.

- ^ Constantin C. Giurescu: History of the city of Bucharest. P. 137.

- ^ University of Karlsruhe - Geophysical Institute, Sibylle Hofmeyer - Earthquake-Proof Building - Unique test arrangement in Bucharest inaugurated on August 31, 1999 , accessed on December 18, 2010.

- ↑ Homepage Allgemeine Deutsche Zeitung für Romania, Peter Derer: Urban development between project and implementation: Bucharest 2000, Is the capital missing its chance to build a modern center? (PDF) accessed on December 25, 2010.

- ↑ Zeitblicke homepage, Armin Heinen: The death of the dictator and the present of the past Romania 1989–2002, Zeitblicke 3, No. 1, 2004 (PDF; 307 kB) , accessed on December 18, 2010.

- ↑ Homepage Rcristea, Romulus Cristea: Construcție subterană în zona Unirii of July 18, 2010 , accessed on December 18, 2010.

- ↑ Kristina Werndl: Romania after the Revolution: A cultural contemporary determination, p. 6, Braumüller-Verlag, Vienna, 2007, ISBN 978-3-7003-1618-3 .

- ^ Homepage Blacksea-commission.org, Convention on the Protection of the Black Sea Against Pollution , accessed December 18, 2010.

- ↑ Bucharest homepage, București development strategy 2000–2008 ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF; 1.2 MB) accessed on January 6, 2011.

- ↑ Der Spiegel: Bucharest - Uprising against the real estate mafia on July 22, 2009.

- ↑ Welt Online: The Stray Dogs of Bucharest from May 14, 1997.

- ↑ Der Spiegel: Action against stray dogs from September 27, 2010.

- ↑ Four-year-old child killed by stray dogs in Bucharest, ORF.at, September 3, 2013 .

- ↑ Jürgen Henkel: Introduction to the history and ecclesiastical life of the Romanian Orthodox Church , Pope John Paul II in Romania, p. 107, Lit Verlag, 2007, ISBN 978-3-8258-9453-5 .

- ↑ Österreichischer Rundfunk (ORF): Anglicans and Catholics coming closer on the Pope question of May 14, 1999 , accessed on December 18, 2010.

- ↑ Homepage Center for OSCE Research, Heinz Vetschera: The Ministerial Council Meeting in Bucharest (PDF; 80 kB), accessed on December 20, 2010.

- ↑ Homepage OSCE, Bucharest Action Plan to Combat Terrorism (PDF) , accessed on December 20, 2010.

- ^ Homepage Konrad Adenauer Foundation Günter W. Dill, Maria Vasiu, Georgeta Voinea: Romania before the Francophonie Summit , Konrad Adenauer Foundation - Bucharest branch, 2006 (PDF) accessed on March 26, 2011.

- ↑ Synthesis Research, Vienna Housing Research: Bucharest - The Urban Population and Their Housing Supply, Housing Policy Monitoring , pp. 5 ff., 2007 (PDF; 87 kB) , accessed on February 21, 2011.

- ^ Federal Agency for Civic Education: NATO summit in Bucharest on April 3, 2008 .

- ↑ Home Thecolosseum , accessed on 28 January 2011th

- ↑ Trigranit homepage , accessed on January 28, 2011.