History of romania

The history of Romania is strongly influenced by the recourse to the Roman era, which is also reflected in the name Romania or rum. România ( French Roumanie ; English Romania ) reflects. Romania was a common name for the Roman Empire in late antiquity and for the area of the Byzantine Empire in the Middle Ages . The Dacians , who lived in what was later to become Romania, were incorporated into the Roman Empire by Trajan in AD 106 and Romanized linguistically and culturally. In 271 the Roman troops were withdrawn to the right bank of the Danube . In the following centuries, with the Bulgarian rule, Christianization took place and the Cyrillic alphabet prevailed, which was abolished in 1862 in favor of the Latin writing system.

Great Migration

Faced with the invasion of Germanic peoples, the administration of the Roman Empire withdrew from Dacia . The last positions north of the Danube were given up during the reign of Aurelian (270-275). Several waves of migration followed, including first that of the Visigoths and the Gepids , then in the 7th century that of the Slavs, mostly settlers, who colonized the lowlands of today's Romania. They came into contact with the Dako-Roman population who still lived in the highlands and were assimilated over the course of centuries of coexistence. Many warrior tribes also moved through the Romanian territory, such as the Huns , the Proto-Bulgarians , the Magyars in the 9th century and the Tatars in the 13th century (see also Migration ).

There is no written evidence of the existence of "proto-Romanians" in the area north of the Danube for the century after Rome's retreat from Dacia. But there is probably no evidence to the contrary. This fact is the reason for a centuries-long feud over Transylvania between Romanian and Hungarian historians .

Some historians claim that the Romanians did not actually descend from the Romanized Dacians, but that they came from south of the Danube and settled in what is now Romania's territory. (For this debate, see: Dako-Romance continuity theory .)

Other historians explain the lack of written evidence to the lack of organized local administration up to the 12th century and the fact that the Mongols destroyed all existing records when the area was looted in 1241 (see also Unorganized State ).

Hungarian migration

In 896 the Magyars settled in the central Carpathian Basin after they had been defeated by the Bulgarians under Tsar Simeon and the Pechenegs in Bessarabia . A century later, Stephan I extended the Hungarian kingdom to Transylvania. The Hungarians built fortresses, founded a Roman Catholic diocese and began evangelizing the Szekler population who had settled there. There are doubts that there were also Romanians among the missionaries, as they were already Christian and remained loyal to the Eastern Orthodox Church after the Eastern Schism . Stephan and his successors recruited German and Hungarian settlers to settle in the region.

Some of the settlers came from far away, including Szekler and the Teutonic Order returning from Palestine , which founded Kronstadt ( Brașov in Romanian ), but then relocated to the Baltic Sea region in 1225 after a conflict with the king. Hungary's kings promoted the loyalty of the colonists by granting them land, trade privileges, and a considerable amount of autonomy. The nobility was limited to Catholics, and while Romanian nobles converted to the Roman Catholic denomination (which eventually led to their Magyarization) in order to preserve their privileges, many Orthodox Romanians became serfs , as did numerous Hungarians and, to a lesser extent, Saxons who lived on the county floor or were settled there by Hungarian nobles as part of internal colonization .

In 1241 the Mongols invaded Transylvania from the north and east across the Carpathian Mountains. They routed Bélas IV's troops , burned down the settlements in Transylvania and central Hungary and murdered part of the population. When the Mongols suddenly withdrew again in 1242, Béla started an energetic reconstruction program. He invited other foreigners to settle in Transylvania and other devastated regions of the kingdom, granted land to local nobles, and ordered stone fortresses to be built. Béla's rebuilding efforts and the extinction of the Árpáden dynasty in 1301 shifted the balance of power in Hungary significantly. The king's influence declined, and rival magnates established smaller kingdoms for themselves, expropriated peasant lands, and tightened feudal duties.

Transylvania became practically independent. As early as 1288, the Transylvanian nobles called their own meeting of the estates. Under increasing economic pressure from uninhibited feudal lords and religious pressure from zealous Catholics, many Romanians emigrated from Transylvania east and south across the Carpathian Mountains and made a decisive contribution to the establishment of the principalities of Moldova and Wallachia.

Medieval states

Early Romanian states emerged in the 10th and 11th centuries and appear in historical sources under the name Wlachen (see also Wallachians ). Most of these states were small kingdoms that usually fell apart after the death of their chiefs.

From 1061 to 1171 Wallachia formed the core empire of the Turkic Pechenegs , then from 1171 to 1240 Wallachia and Moldavia belonged to the empire of the Turkic Cumans . Some historians (including Romanian) claim that Romanians did not advance into the lower parts of Great Wallachia and Moldavia until these areas were cleared by Pechenegs and Cumans. From the end of the 10th century ( Svyatoslaw I ) to the beginning of the 14th century, large parts of Moldova were repeatedly under the direct rule or indirect sovereignty of East Slav princes ( Kievan Rus , Halych-Volhynia ).

The larger principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia did not emerge until the 14th century . Transylvania at that time was an essentially autonomous part of the Hungarian Kingdom, a result of the conquest of the pre-existing smaller political formations in the 11th – 13th centuries. Century.

Wallachia and Moldova

Legend has it that in 1290 Negru Vodă , a leading Romanian nobleman, left Fagarash in southern Transylvania with a group of nobles and founded Țara Românească in the area between the southern Carpathians and the Danube . The name literally means "Romanian land" and actually refers to Wallachia. The word Wallachia is derived from the Slavic word Vlach , which in turn is derived from the Germanic Walh , which originally comes from the Celtic neighbors of the Volcae (Germanic * Walhos ), "Celts" in general, then "Strangers" in general and also "Romane" or "Latin speakers “Meant.

A second legend tells that a Romanian voivode named Dragoș crossed the Carpathian Mountains and settled with other Romanians in the plain between the mountains and the Black Sea. They were joined in 1349 by a Transylvanian voivode named Bogdan, who rebelled against his liege lord and settled on the Moldova river, which gives the Moldova its name. Bogdan declared Moldovan independence from Hungary a decade later. The Romanian nobles who stayed behind in Transylvania eventually adopted the Hungarian language and culture. The Romanian serfs in Transylvania continued to speak Romanian and adhered to the Orthodox faith; but they were powerless to withdraw from Hungarian rule.

Apart from the above-mentioned legends, the principalities of Wallachia and Moldavia were initially set up by the Hungarian king as buffer zones or border marks to protect the Hungarian kingdom from the migrant peoples invading from the north-east and south. The principalities received their political independence in 1330 (Wallachia) and 1359 (Moldova).

Wallachia and Moldova gradually gained power in the course of the 14th century, a peaceful and prosperous time for Southeastern Europe. Prince Basarab I of Wallachia (approx. 1330–1352) had to continue to recognize Hungarian sovereignty , although he won a victory against the first Hungarian Anjou king, Charles I , in 1330 . The Patriarch of the Orthodox Church in Constantinople, on the other hand, established an ecclesiastical seat in Wallachia and appointed a metropolitan. Recognition by the Church confirmed Wallachia's status as a principality, and Wallachia freed itself from Hungarian sovereignty in 1380.

The princes of Wallachia and Moldavia had almost absolute power; only the prince had the power to distribute land and to confer titles of nobility. Meetings of nobles, or boyars , and the higher clergy elected princes for life, and the absence of a succession law created a fertile atmosphere for intrigue. From the 14th to the 17th centuries, the history of the principalities abounds in the overthrow of princes by rival parties, often supported by strangers. The boyars were exempt from paying taxes, with the exception of taxes on the main sources of agricultural property. Although the peasants had to give part of their income in kind to the local nobles, apart from their subordinate position, they were never denied the right to own land or to relocate.

After their founding, Wallachia and Moldova had a similar political, social and economic structure. The state, the political organization and the self-image were strongly based on the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) model of Constantinople. Nonetheless, the development of both principalities remained afflicted with chronic obstacles: Excessive fiscal policy strangled the already inefficient agricultural economy, and the ongoing political instability did not promote the development of stable internal markets and cities. So the development of a significant commercial life remained in the hands of foreign merchants. Over time, trade between the Mediterranean countries and the Black Sea region developed. Merchants from Genoa and Venice established trading centers along the Black Sea coast, where Tatars, Germans, Greeks, Jews, Poles, Ragusians and Armenians exchanged goods. The Romanians (Wallachians and Moldovans), however, remained essentially an agricultural people.

Transylvania

In Transylvania, economic life recovered quickly after the Mongol invasion. New cultivation methods brought with them by the German colonists from Western Europe boosted the crop yield. Craftsmen formed guilds when the craft flourished; Gold, silver and salt mining was expanded, and money-based deals replaced the exchange of goods.

Although the townspeople were exempt from feudal duties thanks to royal privileges and in accordance with medieval town law, feudalism expanded and nobles tightened their obligations. The serfs rebelled against the higher payments; some left the country while others became outlaws. In 1437 Romanian and Hungarian peasants rose up against their feudal lords. The uprising gained momentum, but was finally suppressed at great expense by the combined forces of the Hungarian nobles and with the support of the Saxons and Szeklers in Transylvania. As a result, the Union of the Three Nations (Hungarian nobility, National University of the Saxons and Szeklers) was formed, which vowed to defend its privileges against all powers except that of the Hungarian king.

The document declared the Hungarians, Germans and Szeklers to be the only recognized nations in Transylvania. From then on, all other nationalities there, especially the Romanians, were only "tolerated". In the medieval sense, however, nations are to be understood as classes and not as ethnic groups. The nobility gradually imposed even harsher conditions on their serfs. In 1437, for example, every serf had to work one day a year at harvest time for his liege lord without pay; In 1514, serfs had to work for their master one day a week, with their own animals and tools.

Under Ottoman suzerainty

In the 14th century, the Ottoman Empire expanded from Asia Minor to the Balkan Peninsula. The Ottomans crossed the Bosporus in 1352 and defeated the Serbs in the Battle of the Blackbird Field in 1389 . Tradition has it that the Wallachian prince Mircea cel Bătrân (1386–1418) sent his army to Kosovo to fight alongside the Serbs. He also succeeded temporarily in building a certain position of power south of the Danube. However, this came to an end in 1393 when Bayezid I conquered the Bulgarian Empire (see History of Bulgaria # Ottoman rule ). As a result, many Bulgarian scholars and nobles fled to the Principality of Wallachia , which now became a direct neighbor of the Ottoman Empire on the Danube.

Bayezid I continued his campaign northwards: in 1394 he crossed the Danube and invaded Wallachia, but Mircea inflicted a serious defeat on him on October 10, 1394 in the Battle of Rovine . In 1395 Mircea concluded an alliance with the Hungarian King Sigismund of Luxemburg in Brașov . As a result, he joined his army in a crusade initiated by Sigismund in 1396. The campaign ended in catastrophe: The Ottomans routed Sigismund's army in 1396 at the Battle of Nicopolis in what is now Bulgaria. Encouraged by this victory, the Ottomans invaded Wallachia again the following year, but Mircea again threw the Turkish expedition back across the Danube. Another Ottoman attempt to conquer Wallachia was successfully repulsed by Mircea and his army in 1400.

In 1402 Wallachia got a reprieve from pressure from the Ottoman Empire, as the Mongol leader Tamerlan invaded Asia Minor from the east, killed the sultan and caused a civil war. In 1404, Mircea even succeeded in recapturing the Dobruja province, which had been lost to the Turks . When order returned to the empire after the Ottoman Interregnum , the Ottomans renewed their attack on Wallachia. Towards the end of his rule in 1417, Mircea concluded an agreement with Sultan Mehmed I , whereby he bought his country's independence with an annual tribute payment of 3,000 gold coins. Brăila , Giurgiu and Turnu fell directly to the Ottoman Empire by 1829.

After Mircea's death in 1418, Wallachia and Moldavia experienced a period of decline. Succession struggles, Polish and Hungarian intrigues and corruption produced a series of eleven princes within just 25 years. As the Ottoman threat increased, the principalities were weakened. In 1444 the Ottomans struck again a European campaign near Varna in what is now Bulgaria. When Constantinople was conquered in 1453, the Ottomans cut off the Genoese and Venetian galleys from the Black Sea ports. Trade declined and the isolation of the Romanian principalities increased, although, unlike the more southern Balkan countries, they were able to escape direct Ottoman rule.

At that time, Johann Hunyadi became Imperial Administrator of Hungary. Hunyadi, a hero from the Turkish wars, mobilized Hungary against the Ottomans and equipped a mercenary army, which was financed for the first time from a tax imposed on the Hungarian nobility. He scored a resounding victory over the Turks in front of Belgrade in 1456, but died of the plague soon after the battle.

In one of his last steps, Hunyadi brought Vlad Țepeş (1456–1462) to the throne of Wallachia. Vlad became known for cruelly executing enemies. He hated the Turks and challenged the Sultan by refusing to pay tribute. In 1461 Hamsa Pasha tried to lure him into a trap, but the Wallachian prince discovered the betrayal and had Hamsa and his men captured and staked. Sultan Mehmed II later marched into Wallachia and forced Vlad into exile in Hungary. Vlad returned to the throne for a short time, but died a little later, whereupon the resistance of Wallachia against the Ottomans weakened.

The Moldau and its prince Ștefan cel Mare ( Stefan the Great , 1457–1504) were the principality's last hope to meet the threat from the Ottoman Empire. Stefan raised an army of 55,000 men from the Moldavian peasantry and repulsed the invading lord of the Hungarian King Matthias Corvinus . Stefan's army marched into Wallachia in 1471 and defeated the returning Ottoman army in 1473 and 1474. After these victories, Stephen asked Pope Sixtus IV to call a Christian alliance against the Turks. The Pope responded by paying tribute to Stefan as Athleta Christi , but ignored his demand for a united approach of Christianity. During the last decades of Stefan's reign, the Ottomans increased pressure on Moldova. They captured important Black Sea ports in 1484 and set fire to the Moldavian capital, Suceava , in 1485 . Stefan achieved another victory the following year, but then limited his efforts for the independence of Moldova to diplomatic territory. On his death bed he is said to have advised his son to submit to the Turks if they were to offer an honorable suzerainty. Succession struggles weakened the Vltava after his death.

In 1514, exploitation by the nobility and a badly planned crusade led to an extensive peasant revolt in Hungary and Transylvania. Well-equipped farmers under György Dózsa plundered goods across the country. Despite their large number, however, the peasants were poorly organized and suffered a decisive defeat at Temesvar . Dózsa and the other leaders were tortured and executed. After the uprising, the Hungarian nobility passed laws that tied the serfs to their clods forever and increased their work duties.

Now that serfs and nobility were deeply estranged from each other and various magnates competed with the king for power, Hungary became vulnerable to external attack. The Ottomans stormed Belgrade in 1521, defeated a Hungarian army at Mohács in 1526 and captured Buda in 1541 . They installed a pasha for the government of central Hungary; the Habsburgs controlled parts of northern and western Hungary. Transylvania became an autonomous principality under Ottoman suzerainty.

After the fall of Buda, Transylvania, albeit a vassal state of the Sublime Porte , experienced a period of far-reaching autonomy. As a vassal, Transylvania paid an annual tribute to the Porte and gave military support; in return, the Ottomans promised to protect Transylvania from external threats. Local princes ruled Transylvania from 1540 to 1690. Transylvania’s powerful, mostly Hungarian, ruling families, ironically strengthened by Hungary’s collapse, usually elected the prince who had to be confirmed by the Porte; in some cases, however, the Ottomans appointed the prince in advance. The Transylvanian Estates Assembly became a parliament and the nobility renewed the Union of Three Nations, which still excluded the Romanians from political power. The princes took measures to separate the Transylvanian Romanians from those in Wallachia and Moldova and prohibited Orthodox priests from entering Transylvania from Wallachia.

After Hungary's collapse, the Protestant Reformation spread rapidly in Transylvania and the region became one of Europe's Protestant strongholds. Transylvanian Germans adopted Lutheranism and many Hungarians converted to Calvinism. However, the Protestants who had catechisms printed and distributed in Romanian hardly succeeded in luring the Romanians out of Orthodoxy. In 1571 the Transylvanian state parliament passed a law granting freedom of belief and equal rights to four religions in Transylvania: the Roman Catholic, the Lutheran, the Calvinist and the Unitarian. The law was one of the first of its kind in Europe, but the religious equality it proclaimed was limited: Orthodox Romanians, for example, were free to practice their religion, but they did not enjoy political equality.

After the conquest of Buda by the Ottomans, the pressure of the Ottoman Empire on Wallachia and Moldova increased. In the 170 years that followed, the two Romanian principalities gradually came under more and more dependence on the Sublime Porte, even if their status remained that of vassal states: Wallachia and Moldova secured extensive internal independence for themselves in return for the payment of increasing tribute in the 18th century even a certain leeway in foreign policy. The Ottomans chose the Wallachian and Moldavian princes among the sons of noble hostages or refugees. Few princes died of natural causes, but lived in great luxury during their reigns. As in the case of Transylvania, the two principalities also undertook to provide military support to the Sublime Porte and in return received the promise of the Ottomans to be protected from external threats.

The last serious Wallachian resistance came from Prince Mihai Viteazul ( Michael the Brave , 1593–1601). After he was enthroned, his army took several Ottoman fortresses. Ultimately, Mihai's goal was complete independence. For this purpose, in 1598, he first pledged allegiance to the Roman-German Emperor Rudolf II . A year later, Mihai took Transylvania, and his victory incited the Transylvanian peasants to rebellion. Mihai, however, was more interested in endorsing the Transylvanian nobility and less in supporting unruly serfs. He suppressed the uprising, but despite the prince's promises, the nobles distrusted him. In 1600 Mihai finally conquered the Vltava.

In 1600 a Romanian prince ruled over all Romanians in Wallachia, Moldova and Transylvania for the first time for four months. Mihai's success startled Rudolf. The emperor incited the Transylvanian nobility to revolt against the prince, and at the same time Poland invaded Moldavia. Mihai consolidated his forces in Wallachia, apologized to Rudolf and agreed to a campaign together with Rudolf's general Giorgio Basta , with which Transylvania was to be won back from rebellious Hungarian nobles. After her victory, Basta had Mihai killed for alleged treason. Mihai Viteazul (Michael the Brave) became more impressive in the legend than he was in his life, and his brief unification of the Romanian territories later inspired the Romanians to struggle for their cultural and political unity.

In Transylvania, Basta's army persecuted Protestants and illegally expropriated their property until Stephan Bocskay (1605-1607), a former supporter of the Habsburgs, called up an army that drove the imperial troops out of the country. In 1606, Bocskay signed peace treaties with the Habsburgs and the Ottomans , which secured his position as Prince of Transylvania, guaranteed religious freedom and extended Transylvania’s autonomy.

After Bocskay's death and the reign of the tyrannical Gabriel Báthory (1607–1613), the gate forced the Transylvania to accept Gábor Bethlen (1613–1629) as prince. Transylvania lived a golden age under Bethlen's enlightened despotism. He encouraged agriculture, trade and industry, had new mines opened, sent students to Protestant universities abroad, and forbade landlords from denying their serfs' children an education.

After Bethlen died, the Transylvanian state parliament reversed most of its reforms. Soon after, György Rákóczi I (1630–1640) became prince. Like Bethlen, Rákóczi sent Transylvanian troops to the Thirty Years' War to fight on the side of the Protestants; In the Peace of Westphalia , Transylvania was mentioned as a sovereign state. The golden age ended after György Rákóczi II (1648–1660) had started an unfortunate attack on Poland without consulting the Porte or the state parliament beforehand. A Turkish and Tatar army defeated Rákóczi's army and occupied Transylvania. For the remainder of its independence, Transylvania had to endure a number of weak leaders, and throughout the 17th century its Romanian peasants remained in poverty and ignorance.

During Mihai's brief tenure and the early years of Ottoman suzerainty, the distribution of land within Wallachia and Moldova changed dramatically. Over the years Wallachian and Moldovan princes granted local boyars property in return for military service, so that by the 17th century there was hardly any land left. In search of prosperity, boyars began to encroach on peasant lands and their military loyalty to the prince waned. As a result, serfdom spread, successful boyars became more courtiers than warriors, and an intermediate class of impoverished lowly nobles developed. Would-be princes were forced to pay their way to power with huge bribes, and peasant life was made even more miserable by taxes and collections. Any prince who sought to improve the lives of the peasants risked a financial deficit that could enable rivals to outdo him at the gate and seize his post.

1632 came with Matei Basarab (1632-1654) the last of the predominant Wallachian family on the throne; two years later, Vasile Lupu (1634–1653), a man of Albanian origin, became Prince of Moldova. The jealousy and ambition of Matei and Vasile undermined the strength of the two principalities at a time when the power of the Porte was beginning to wane. Targeting the more attractive Wallachian throne, Vasile attacked Matei, but his army defeated the Moldovans and a group of Moldovan boyars ousted Vasile. Both Matei and Vasile, however, were enlightened rulers who generously supported religion and the arts, set up printing presses, published religious books and codes of law, and founded large monasteries that developed into important supraregional cultural and educational centers, such as the Căldăruşani monastery in Wallachia and Trei Ierarhi in the capital of Moldova.

The cultural, social and economic life in Wallachia flourished under the rule of Constantin Brâncoveanu (1654–1714), prince from 1688 to 1714. At the same time, the Cantemir family ruled in the Principality of Moldova. As in the first half of the 17th century, the conflict between the two principalities weakened their foreign policy situation. Brâncoveanu and Dimitrie Cantemir negotiated at the same time with Tsar Peter I (Russia) and tried to conclude an alliance with him against the Turks, but at the same time disclosed the intentions of the other to the Sublime Porte in order to weaken his position. After the death of Brâncoveanu and his 4 sons, who were beheaded in Constantinople, and after Dimitrie Cantemir's flight to Russia, the so-called Phanariot period began in Wallachia and Moldova. From now on the princes were no longer elected by the local boyars, but appointed by the Sublime Porte from the Greek elite in Constantinople. The two principalities continued to play an important cultural and religious role in south-eastern Europe. Since, unlike the neighboring countries south of the Danube, they were not exposed to Islamic influences, they became a refuge for many Christian scholars. In addition, the Wallachian and Moldovan princes were able to support the Orthodox monasteries of Mount Athos, Syria, Egypt, Palestine and Sinai for centuries. So appeared z. B. 1711 the first Bible in Arabic script for the Syrian Christians with the financial help of Constantin Brâncoveanu.

Towards the end of the 17th century, after the victory against the Ottomans, Hungary and Transylvania became part of the Habsburg Empire.

The period between 1711 and 1821 is referred to in Romanian historiography as the “ Phanariot period ”, a time of decline and national disaster. Wallachia and Moldova lost all appearances of their independence, and the Porte demanded considerable tribute payments. Members of important Greek families from the Phanar district in Constantinople were appointed to be ruling princes in the principalities - hence the name "Phanarioti". Although the old state treaties ("capitulations") between the Sublime Porte and the Romanian principalities forbade the Ottoman subjects to settle in the principalities, to marry, to buy land or to build mosques there, the princes now allowed Greek and Turkish traders and usurers to exploit the riches of the principalities. By jealously defending their privileges, the Greeks inhibited the developing Romanian middle class. At this time, the Romanian principalities recorded heavy territorial losses. As a result of the Treaty of Passarowitz , Wallachia and Little Wallachia lost their western part to the Habsburg Empire in 1718 , but received this "Oltenia" back in 1739 in the Treaty of Belgrade . In 1775 Austria occupied the northwestern part of the Vltava, the Bukowina , the "beech country". In 1812 Russia occupied Bessarabia , the eastern half of the principality, and was awarded the part of the country between Prut and Dniester in the Treaty of Bucharest .

From the beginning of the 19th century, Russia gained increasing influence in the Danube principalities at the expense of the Ottoman Empire. During the Russo-Turkish War (1828–1829) Russian troops occupied Wallachia and Moldova for a few years; The Tsar had his say in the Peace of Adrianople (1829) and in the Organic Regulations - the first constitutional piece of legislation in the forerunner states of Romania - confirmed.

Romanian Revolution of 1848

During the period of Austrian rule in Transylvania and Ottoman suzerainty over most of the rest of Romanian territory, most ethnic Romanians had to be content with a role as second class citizens. In most Transylvanian cities, however, Romanians were not even allowed to live within the city walls.

During the Romantic era , as among many other peoples in Europe, a national consciousness developed among the Romanians. Seeing themselves in contrast to the nearby Slavs, Germans and Hungarians, the nationalistic Romanians looked to other Romance countries, especially France, for role models for nationality.

In 1848, as in many other European countries, there were uprisings in Moldova, Wallachia and Transylvania. Although the rebels were initially unable to achieve their goals and were denied full independence for Moldova and Wallachia as well as national emancipation for Transylvania, the basis for the following developments was created, since the population of the three principalities in the course of the clashes from the Unity of their language and interests.

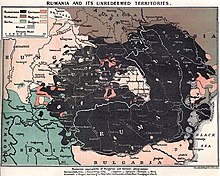

Heavily taxed and badly administered, the people of both Moldova and Wallachia elected the same person - Alexandru Ioan Cuza - to be their prince. Thus came Romania, albeit a Romania without Transylvania, where Romanian nationalism inevitably clashed with Hungarian nationalism. For some time, Austria-Hungary , especially under the dual monarchy of 1867, was to give the Hungarians firm control even in those parts of Transylvania where the Romanians made up a local majority.

Kingdom of Romania

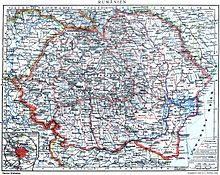

The election of Alexandru Ioan Cuza as prince of both Moldova and Wallachia under the nominal suzerainty of the Ottoman Empire in 1859 united an identifiable Romanian nation under a common ruler. On December 8, 1861, Alexandru Ioan Cuza proclaimed the formation of the Principality of Romania from the Danube Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia. In 1862 the two principalities were also formally united and formed Romania with Bucharest as the capital.

Under pressure from the so-called “monstrous coalition” of conservative and radical liberals, Cuza had to abdicate on February 23, 1866. The German Prince Karl von Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen was appointed Prince of Romania with the ulterior motive of ensuring Prussian support for unity and future independence. His descendants would rule as kings of Romania until the fall by the communists in 1947.

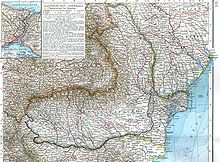

After the Russo-Turkish War of 1877/78, in which Romania fought alongside Russia against Turkish rule, Romania was recognized as independent by the Treaty of Berlin in 1878 (→ Berlin Congress ). The Dobrudscha was added to it as territory, but at the same time it had to cede the three districts of Cahul, Bolgrad and Ismail in southern Bessarabia in the area of the Danube estuary to Russia (this corresponded to about a quarter of the Moldavia, to which the area belonged until then). The principality proclaimed itself the Kingdom of Romania on March 26, 1881 , and Charles became the first King of Romania as Carol I. The new state, wedged between the Ottoman Empire, Austria-Hungary and Russia with Slavic neighbors on three sides, looked to the west for cultural and administrative models, especially France. Today this state is also called Altreich .

Germany and Austria-Hungary, which had formed the Triple Alliance with Italy in 1882 , tried to bind Romania to them in order to prevent Romania from taking the side in the event of a conflict; Romania joined the Triple Alliance in 1883. In the First Balkan War in 1912/13 Romania remained neutral, in the Second Balkan War the country took part in the coalition against Bulgaria, which emerged as a loser from the war and had to cede southern Dobruja to Romania. During the First World War , too , they remained neutral for the time being; since Austria-Hungary had declared war on Serbia, there was no alliance commitment.

First World War

In the course of the war, however, the constellations changed. Italy declared war on the Central Powers and Bulgaria entered the war on the side of the Central Powers. Prime Minister Ion IC Brătianu tried in vain to compensate for the neutrality of Romanian-speaking areas in Transylvania and Bukovina . On August 17, 1916, Romania signed an alliance treaty with the Entente . In it, Romania was assured almost all of Bukovina (south of the Prut ), Transylvania and the Temesvár Banat. On August 27, 1916, Romania entered the war on the side of the Entente; Romania's war target was the areas of Austria-Hungary, which were predominantly Romanians. The Romanian army was militarily extremely unhappy, and within a few months all of Wallachia was occupied by German, Austro-Hungarian and Bulgarian troops. Only with Russian help could the Romanian army stop the enemy advance in the summer of 1917. On March 5, 1918, the preliminary peace of Buftea came about. On May 7, 1918, Romania concluded the Treaty of Bucharest with the Central Powers . The Romanians of Transylvania spoke on December 1, 1918 in the “Karlsburger Decisions” ( Alba Iulia ) for unification with Romania. The Germans of Transylvania supported this decision on December 15, 1918 in Mediasch , while the Hungarians spoke out against it on December 22, 1918 in Cluj- Napoca. The new Romanian state, however, only fulfilled part of the promises made to the minorities in the Karlsburger Decisions.

Interwar period

Before that, Romania had re-entered the war at the beginning of November, which, after the end of the fighting against the Central Powers, turned into the Hungarian-Romanian War for predominantly Romanian-populated areas in the same month and in August 1919 with the occupation of Budapest and the end of the Soviet Republic of Hungary under Béla Kun ended. With this military position, Romania benefited from a favorable military-political boom at the Paris Peace Conference : Because Austro-Hungary and the Russian Empire had disintegrated, it was able to raise extensive territorial demands in the peace negotiations, namely those areas where there was an absolute Romanian majority gave. However, Romania was also granted areas that were mostly inhabited by Hungarians, such as the Szeklerland and numerous border towns in the north and northwest. Government bodies formed in Transylvania , Bessarabia and Bukovina opted for union with Romania, which was confirmed in the Treaty of Trianon in 1920.

In the new " Greater Romania " three quarters of the population were ethnic Romanians. Numerous minorities lived in Transylvania, the Banat, Bukovina, Bessarabia and Dobruja. The most important minorities were the Hungarians (7.9%), Germans (4.1%), Jews (4%) and Ukrainians / Russians (3.2%); there were also Russians (2.3%), Bulgarians (2%), Roma / Gypsies (1.5%), Turks (0.9%), Gagauz (0.6%) etc. But also the number of Romanians who lived in the neighboring states along the borders of Greater Romania was not insignificant: 250,000 in the Soviet Union (including 172,419 in the Autonomous Republic of Moldova ), 230,000 in Yugoslavia in the Serbian Banat and in central Serbia , 60,000 in Bulgaria (including 42,414 in the region of Widin ) and 24,000 in Hungary.

Most of the governments in the interwar years retained the form but not the substance of a liberal constitutional monarchy. The 1923 constitution gave the king the power to dissolve parliament and call elections at will; As a result, there were over 25 different governments between 1930 and 1940. The national liberal party, which dominated in the years immediately after the First World War, became increasingly nationalist and was replaced in power by the national peasant party in 1927.

During this time the relationship between the nationalist parties and King Carol II was marked by mutual distrust. After the death of his father Ferdinand in 1927, Carol was prevented from acceding to the throne because of his famous Jewish mistress Magda Lupescu. After three years in exile, during which his brother Nicolae served as regent and his young son Mihai as king, Carol publicly gave up his mistress and ascended the throne herself; but it quickly became clear that his renunciation was a delusion.

In the 1930s a number of ultra-nationalist parties rose, in particular the quasi-mystical fascist movement of the Iron Guard (also: "Legion of the Archangel Michael"), which promoted nationalism , the fear of communism and resentment against the alleged foreign and Jewish Took advantage of dominance in the economy. On December 10, 1933, Liberal Prime Minister Ion Duca disbanded the Iron Guard and arrested thousands; 19 days later he was murdered by legionnaires of the Iron Guard on a platform at Sinaia train station .

On February 10, 1938, King Carol II dismissed the government and instituted a royal dictatorship to prevent the formation of a government that would have included ministers from the Iron Guard. This happened in direct confrontation with Adolf Hitler's express support for the Iron Guard.

Over the next two years, the already fierce conflict between the Iron Guard and other political groups under several short-lived governments turned into almost civil war. In April 1938, Carol had the Iron Guard leader, Corneliu Zelea Codreanu, arrested. On the night of November 29th to 30th, 1938, presumably in revenge for a series of assassinations by Iron Guard commands, Codreanu and several other legionaries were killed, allegedly while attempting to escape. It is generally believed that such an attempt to escape did not take place.

The king's dictatorship was short-lived. On March 7, 1939, a new government was formed with Armand Călinescu as Prime Minister; on September 21, 1939, three weeks after the outbreak of World War II , Călinescu was again murdered by legionnaires as revenge for Codreanu.

Second World War

At the beginning of the Second World War, Romania initially tried to remain neutral. On April 13, 1939, France and Britain had committed themselves to securing Romania's independence, but negotiations for a similar guarantee by the Soviet Union were broken off after Romania refused to allow the Red Army to be present on its territory. On August 23, Vyacheslav Mikhailovich Molotov and Joachim von Ribbentrop signed the German-Soviet non-aggression pact . Eight days later , Germany invaded Poland and Romania gave refuge to members of the Polish government (see Polish government in exile ).

On June 26, 1940, the Soviet Union issued an ultimatum asking Romania to withdraw its troops and administration from Bessarabia , northern Bukovina and the Herza area , otherwise the USSR would begin the military invasion. This move was made possible by the secret additional protocol of the German-Soviet non-aggression pact. Both Germany and Italy had already been informed of the ultimatum on June 24, but had neither informed Romania of this nor were they prepared to provide assistance. Due to France's surrender ( June 22, 1940 ) and Great Britain's withdrawal from the mainland ( Battle of Dunkirk May 26 – June 5, 1940), Romania's western allies were unable to intervene. Romania agreed to the terms to avoid an armed conflict. The Soviet annexation began on June 28th and was completed with the proclamation of the Moldovan Soviet Socialist Republic on August 2nd.

Romania was forced by Germany and Italy through the Second Vienna Arbitration (August 30, 1940) to return the northern half of Transylvania ( Northern Transylvania ) to Hungary (Southern Transylvania remained Romanian). On September 7th Romania undertook to return the southern part of the Dobruja to Bulgaria ( Treaty of Craiova ). These territorial losses shook the very foundations of Carol's power.

The government formed by Ion Gigurtu on July 4, 1940 was the first to include an Iron Guard minister , namely the anti-Semite Horia Sima , who had become the nominal leader of the movement after Codreanu's death. He was one of the few prominent legionaries who had survived the carnage of the past few years.

Antonescu era

The Iron Guard (led by Sima ) and General (later Marshal) Ion Antonescu formed the government of a “national legionary state” on September 4, 1940, which forced the abdication of Carol II in favor of his 19-year-old son Mihai . Carol and Lupescu went into exile, and in the face of the defeat of the protecting power France, Romania had no choice but to move closer to the Axis powers , despite the previously enforced relinquishment of territory .

In power, the Iron Guard tightened the already tough anti-Semitic laws and took revenge on their enemies. More than 60 former dignitaries and officials were executed in Jilava Prison on November 27, 1940 while awaiting trial. Former Prime Minister Nicolae Iorga and economist Virgil Madgearu, also ministers in a previous government, were murdered without arrest. The relationship between the Iron Guard and Antonescu was considered tense. On January 20, 1941, the Iron Guard attempted a coup, combined with a pogrom against the Bucharest Jews, but the coup was crushed by Antonescu within four days and the Iron Guard was expelled from the government. Sima and many other legionaries took refuge in Germany, others were imprisoned.

At the end of November Romania joined the Tripartite Pact and made its territory available as a deployment area for the planned German eastern campaign. The Wehrmacht crossed the Romanian borders on October 8, 1940 and soon reached a troop strength of 500,000 soldiers. On November 23, Romania entered the war on the side of the Axis Powers.

On June 22, 1941, Operation Barbarossa began the German invasion of the Soviet Union. In the southern area of Bukovina and Bessarabia, the attack did not begin until July 2, 1941. The German 11th Army (100,000 men) and the Romanian 3rd and 4th Army (200,000 men in 14 divisions) were involved there. On July 27, the troops reached the Dniester River and advanced into what would later become Transnistria , the conquest of which was completed as far as the Bug River in August 1941. The battle for Odessa lasted until October 1941. Between Romania and the German Reich, the Tighina Agreement was reached on a military level at the end of August 1941 , after which Transnistria was annexed to Romania.

Hitler convinced Antonescu to advance further than the 1940 border. General Petre Dumitrescu led the 3rd Army into the battle of the Sea of Azov . By October 10, the units had moved more than 1,700 kilometers from Romania, fought four major battles and fought 42 minor skirmishes. For the battle of Stalingrad , the High Command of the Army (OKH) ordered large parts of Dumitrescu's troops into the besieged city, which either fell there or were taken prisoner by the Soviets. The defense of the 138 km long section of the front by the remaining units was thereby weakened; an offensive by the Red Army in the southwest broke through the Romanian front and forced the Romanian units to withdraw in December 1943. On the way to Bucharest , the troops were surrounded by the Red Army. The Soviets made more than 130,000 Romanian prisoners of war , and only remnants of the associations were able to reach Bucharest.

Under the Antonescu government, Romania made a significant contribution to supplying Germany and the armies of the Axis powers with supplies of oil, grain and industrial products, but mostly without financial compensation, which resulted in high inflation. The oil fields of Ploieşti were one of the most important sources of raw materials for the Wehrmacht. Allied air strikes on Ploiești were intended to prevent or at least impair the production of essential war goods such as fuel. On August 1, 1943, US planes bombed the conveyors and refineries in Operation Tidal Wave .

Despite the alliances between Hungary and Romania and Germany, the Antonescu regime remained hostile to Hungary on the diplomatic level on the Transylvania question. Before the Soviet counter-offensive in Stalingrad , the Romanian government saw an armed conflict with Hungary on this issue as inevitable for the time after the expected victory over the Soviet Union.

Romania and the Holocaust

Shortly after taking office in 1940, Antonescu declared the Jews of Romania to be stateless unless they had become citizens before the peace treaty was signed. That affected just about all Jews, about 590,000. When Romania entered the war, the Iron Guard's massacre of the Jews began in February 1941 and culminated in the Iași pogrom . Also in the massacres of Odessa in the autumn and winter of 1941, tens of thousands of Jews were Odessa and throughout Transnistria killed. Even after the fall of the Iron Guard, the Antonescu regime, allied with the German Reich , continued a policy of oppression and massacres of Jews and Roma , mainly in the eastern areas. Pogroms and deportations were the order of the day in Moldova, Bukovina and Bessarabia . The number of victims is controversial, but the lowest serious estimates range between 100,000, 250,000 and at least 280,000 Jews and 20,000 to 25,000 Roma in these eastern regions, while 120,000 of Transylvania's 150,000 Jews died under the attack of the Hungarians. Without German pressure, by the time Romania surrendered in August 1944, more than half of the country's Jews had been murdered, and only the new political situation prevented the complete annihilation of the country's Jews .

Royal coup

By 1944, the Romanian economy was on the brink of war spending and Allied bombing, and resistance to skimming by Germany developed even among those in favor of war.

When the front reached Romanian territory in 1944 (see Operation Jassy-Kishinew = major attack on August 20, 1944), King Mihai, until then mainly a representative figure, led on August 23, 1944 with the support of opposition politicians from the center-left spectrum and the Army successfully carried out a coup , which ended Antonescu's dictatorship, partially reinstated the 1923 constitution and brought Romania to the side of the Allies. The new Romanian bourgeois government was led by Prime Minister Nicolae Rădescu . In the battle against Germany, Romania suffered further heavy losses in Transylvania, Hungary and Czechoslovakia.

Although Romanian units were now fighting under Soviet command, the Soviets viewed Romania as occupied territory and stationed troops across the country. The Allied Western Powers recognized this status in the Yalta Conference . The 1946 Paris Peace Conference denied Romania the rank of fellow ally. The territory of Romania shrank significantly compared to its size before the Second World War. Although the Vienna arbitration award was revised and northern Transylvania was placed under Romanian administration again, Bessarabia and northern Bukovina had to be returned to the Soviet Union.

In January 1945, Romania fulfilled Soviet reparations claims for war damage before the change of sides by the deportation of able-bodied Romanian Germans to Soviet labor camps, forced by the Russian occupiers . Herta Müller processed the subject in her novel Atemschaukel .

People's Republic and Socialist Republic

Rise of the communists

In 1945 Petru Groza was appointed Prime Minister by the Frontul Plugarilor, which is close to the communists . Although his government consisted of representatives from most of the major pre-war parties, the key ministries were occupied by the communists. The first government under Groza decided on land reform in March 1945 with extensive expropriations of fields, houses, cattle, agricultural machinery and equipment . Women were also given the right to vote. At the same time, however, it also marked the beginning of Soviet and Communist domination in Romania.

King Mihai, dissatisfied with the course taken by the government, refused to sign new laws in an attempt to force Groza's resignation. Groza decided to let the laws go into effect without Mihai's consent. On November 8, 1945, an anti-communist demonstration in front of the Royal Palace in Bucharest was violently broken up, with numerous arrests, injuries and an indefinite number of deaths.

According to Article 14 of the Armistice Agreement of September 12, 1944 with Romania, the Allied Control Commission , chaired by the Soviet Union, had two people's courts of justice established in Romania to judge war crimes and crimes against humanity after the Second World War . These People's Courts ( Tribunalele Poporului in Romanian ) were located in Cluj and Bucharest. In 1946 and 1947 tens of thousands of members of the regime formerly on the side of the Axis powers were executed as war criminals, including the Army Chief of Staff and former dictatorial Prime Minister Ion Antonescu in Jilava prison near Bucharest on June 1, 1946 . The women's suffrage was introduced 1946th In the elections according to the unified list of November 9, 1946 (cf. Romanian Communist Party ), the communists received 80% of the votes, but this resulted in widespread and sometimes violent election manipulation.

In the spring of 1947, the Groza government crushed the remnants of the opposition with mass arrests and the banning of the two large traditional political groups, the Partidul Național Țărănesc Creștin Democrat (“National Christian Democratic Peasant Party”) and the Partidul Național Liberal (“National Liberal Party "). Farmer leader Iuliu Maniu , then 74 years old, was sentenced to life imprisonment on November 11, 1947 and died eight years later. The leader of the liberals Constantin Brătianu suffered the same fate . After the last liberal ministers around Gheorghe Tătărescu were deposed, King Mihai also abdicated under pressure on December 30, 1947 and went into exile. The "Romanian People's Republic " was proclaimed and founded on April 13, 1948 by a constitution .

Internal party power struggles

The early years of communist rule in Romania were marked by repeated changes of course and mass arrests, and various groups fought for supremacy. In 1948 the earlier agrarian reform was reversed and replaced by a move towards collectivization of agriculture . This resulted in tens of thousands of arrests, as did efforts to eliminate the Uniate Church . On June 11, 1948, all banks and large corporations were nationalized. Romania developed a system of forced labor and political prisons similar to that in the Soviet Union. An estimated 100,000 political prisoners died in an unsuccessful attempt to build a Danube-Black Sea Canal .

There were three important groups, all Stalinist, which differed more in their personal histories than in deeper political or philosophical differences: The emigrants under Ana Pauker and Vasile Luca had spent the war in exile in Moscow. The locals , of whom Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej was the most important, had been in Romanian prisons during the war, especially in Doftana prison , and were therefore called prison groups in Romania . A somewhat less Stalinist group, to which Lucrețiu Pătrășcanu belongs, had saved itself through the Antonescu years by hiding in Romania. She had participated in the broad governments immediately after Mihai's coup.

With Stalin's backing, and probably under the influence of the anti-Semitic policies of late Stalinism (Pauker was Jewish), Gheorghiu-Dej and the locals won the power struggle. Pauker was expelled from the party along with 192,000 other party members during the purges. Pătrășcanu was executed after a show trial.

Gheorghiu-Dej era

Gheorghiu-Dej, a staunch Stalinist, was not impressed by the incipient de-Stalinization in the Soviet Union after Stalin's death in 1953. He also feared the plan of CMEA to make the Eastern bloc from Romania the "bread basket", as he pursued a program to develop heavy industry. He closed Romania's largest labor camp, abandoned the Danube-Black Sea Canal project , stopped rationing and increased workers' wages .

This, combined with the persistent resentment that with the founding of the Moldovan Soviet Republic historically Romanian country had become part of the Soviet Union, led Romania under Gheorghiu-Dej consistently to a relatively independent and nationalist course.

Gheorghiu-Dej identified with Stalinism . In order to consolidate his position, he had Foreign Minister Ana Pauker disempowered and expelled from the party in 1952 . The more liberal thaw after Stalin's death threatened to undermine his authority. Now he promised cooperation with every state - regardless of its political-economic system - as long as it recognized international equality and did not interfere in the internal affairs of other states. These policies strengthened Romania's ties with China, which also advocated national self-determination.

1954 Gheorghiu-Dej resigned as general secretary of the party, but remained chairman. A collective secretariat of four members, including Nicolae Ceaușescu , controlled the party for a year, after which Gheorghiu-Dej took over the reins again. Despite its new policy of international cooperation, Romania joined the Warsaw Pact in 1955 , which led to the subordination and integration of part of its military into the Soviet military machine. Romania later rejected Warsaw Pact maneuvers on its territory and restricted its participation in military maneuvers in other countries of the alliance.

In 1956, Soviet Prime Minister Khrushchev branded Stalin in his secret address to the XX. Party congress of the CPSU . Gheorghiu-Dej and the leadership of the PMR were strengthened to survive the de-Stalinization. Gheorghiu-Dej made Pauker, Luca and Georgescu the scapegoats for the excesses of Romanian communists in the past, claiming that the Romanian party had purged the Stalinist elements before Stalin's death.

In October 1956, the communist leaders in Poland resisted Soviet military threats to meddle in domestic affairs and set up a more docile Politburo. A few weeks later the communist party in Hungary practically dissolved during a revolution. The Polish October and Hungarian uprisings inspired Romanian students and workers to demonstrate in universities and workers' cities for freedom, better living conditions and the end of Soviet domination, for example in the student uprising in Timișoara in 1956 . Since Gheorghiu-Dej feared that a Hungarian uprising could incite the Hungarian people to revolt in his own country, he advocated rapid intervention by the Soviets. The Soviet Union increased its military presence in Romania, particularly along the Hungarian border. Although the riots in Romania proved fragmented and controllable, those in Hungary were not, and so Moscow launched a bloody invasion of Hungary in November.

After the revolution of 1956, Gheorghiu-Dej worked closely with Hungary's new leader, János Kádár . Although Romania initially took in exiled former Hungarian Prime Minister Imre Nagy , it extradited him to Budapest for trial and execution. In return, Kádár gave up the Hungarian claims to Transylvania and denounced Hungarians, who had supported the revolution there, as chauvinists, nationalists and irredentists.

Romania's government took measures to alleviate the discontent in the country by reducing investment in heavy industry, increasing the production of consumer goods, decentralizing economic management, increasing wages and introducing elements of workers' self-government. The authorities abolished mandatory supplies by private farmers, but accelerated the collectivization program in the mid-1950s, albeit less brutally than before. The government declared collectivization complete in 1962; at that time, collective and state courts held 77% of the arable land.

Despite Gheorghiu-Dej's claim that he purged Stalinists from the Romanian party, he remained vulnerable to attack between 1944 and 1953 because of his apparent complicity in party activities. At a general assembly of the PMR in March 1956, Miron Constantinescu and Iosif Chișinevschi , both politburo members and deputy prime ministers, criticized Gheorghiu-Dej. Constantinescu, who campaigned for Khrushchev-style liberalization, posed a particular threat to Gheorghiu-Dej because of his good relations with the Moscow leadership. The PMR removed Constantinescu and Chișinevschi in 1957 by denouncing them as Stalinists and accusing them of complicity with Pauker. After that, Gheorghiu-Dej did not have to fear any serious challenge to his leadership role. Ceaușescu replaced Constantinescu at the top of the PMR squad.

Gheorghiu-Dej never reached a truly mutually acceptable agreement with Hungary over Transylvania. Gheorghiu-Dej approached the problem from two sides: by arresting the leaders of the Hungarian People's Union and by establishing an autonomous Hungarian region (Regiunea Autonoma Maghiara) in Szeklerland in 1952 .

Ceaușescu era

Gheorghiu-Dej died in unclear circumstances in 1965 (apparently while he was in Moscow for medical treatment). After an inevitable power struggle, the previously inconspicuous Nicolae Ceaușescu became his successor. Where Gheorghiu-Dej had followed a Stalinist line while the Soviet Union was in a phase of reform, Ceaușescu now appeared first as a reformer, and that at a time when the Soviet Union under Leonid Brezhnev was heading in a neo-Stalinist direction.

In his early reign, Ceaușescu was popular both domestically and abroad. Agricultural goods were abundant, consumer goods reappeared, and there was a period of political thaw . Abroad it was noted that he spoke out against the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968 . While his domestic standing soon faded, he continued to enjoy unusually good relations with Western governments and with institutions such as the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank because of his independent political stance . Under Ceaușescu, Romania maintained diplomatic relations with the Federal Republic of Germany, Israel, China and Albania, among others.

The phase of freedom and apparent prosperity, however, should only be short. In an attempt to increase the birth rate , Ceaușescu enforced a law restricting abortion and contraception : both were only allowed to women over 40 and those with at least four children; In 1972 these limits were raised to 45 years or five children. In the 1980s he went even further: Compulsory gynecological exams were designed to identify women who were circumventing their "patriotic responsibility" to give birth. Tax rates were changed to discriminate against singles and childless people. However, many women, especially those in need, tried to secretly abort their unborn child with wires or drugs. Birth control pills , contraceptives, and even expired abortion pills have been traded on the black market. As a result of these attempts at abortion (but also the poor diet), 11,000 women died, and massive numbers of disabled children were born and deported to orphanages. At the age of three, they were examined by a medical committee that decided on their fate. Then the Securitate secret police took their offspring from the orphanages. The chronically ill children, the children with developmental defects due to malnutrition and those left behind were taken to homes such as B. Cighid deported. Most of them died of hunger and disease after just a few weeks, or they simply froze to death.

While Gheorghiu-Dej's attitude towards the Hungarian minority was still ambiguous, Ceaușescu was openly repressive. Hungarian language schools, publishing houses and cultural institutions have largely been closed. Ethnic Hungarians were urged to traditionally give their children Romanian names. Jews and Germans fared relatively better: they were useful as bargaining chips in relation to the German and Israeli governments. With the free purchase of Romanian Germans by the German federal government from 1967 to 1989 under the code name top secret channel the departure of 226,654 Romanian Germans from Romania sought in the Federal Republic of Germany. The amount of the payments for the so-called bounty is estimated at over 1 billion DM. Romania and the young state of Israel concluded an economic agreement as early as July 1948, which, among other things, provided for the emigration of 5,000 Jews per month at a cost of 8,000 lei per person. The Joint Distribution Committee agreed to bear these costs. A total of 118,000 Jews left the country for Israel between May 1948 and the end of 1951. As a further compensation, poultry farms and other agricultural businesses were supplied by Israel.

Other violations of human rights were typical of a Stalinist regime: the massive use of the secret police (the Securitate ), censorship, massive resettlements, if not on the same scale as in the 1950s. The whole of Bucharest was subjected to a tunnel system for the Securitate, as it turned out during the 1989 uprising.

Ceaușescus Romania continued Gheorghiu-Dej's policy of industrialization, but still produced few goods that could qualitatively compete on the world market. After a visit to North Korea , Ceaușescus developed a megalomaniac vision to completely rebuild the country; this became known as the Village Systematization Program . Whole cities, and eventually a large part of the capital Bucharest , were torn down and replaced either with bland concrete buildings or (if money ran out) with nothing; this fate met u. a. Parts of the historic old town of Bucharest including the Jewish shtetl .

Despite everything, and despite the appalling treatment of the “redundant” or sick children, the country continued to have a good school system and, in general, a good health system. However, both were shattered by the corruption in Romania, which is increasingly necessary for survival : Operations and entrance exams at universities had to be “paid” in kind or in cash, and people over 60 often received no medical care at all. Not every industrialization project failed: Ceaușescu left Romania with a fairly effective system of energy generation and transmission, which was inoperable in the last years of his rule. The thermal power stations, which also had to burn lignite and tar slate, were partially operated with black earth, and the necessary thermal heat was not achieved. The temperature in houses was at times 12-14 ° C, and the electricity was switched off in the morning, evening and night. Bucharest received a working metro . New blocks of flats were built in many cities, and the old buildings were sometimes razed to the ground on the personal orders of Elena Ceaușescu.

In the 1980s, Ceaușescu similarly became obsessed with the idea of repaying western debts that had piled up to threaten Romania with national bankruptcy , and building a "Palace of the People" ( Palatul Poporului ) of unprecedented proportions, along with one alike grandiose surroundings, the Centru Civic . There was also a resurgence of efforts to build a Danube-Black Sea Canal. This led to unprecedented levels of poverty for the average Romanian. There was no meat to buy because it was sold abroad for foreign currency . There was no marble for tombstones because it was needed for the construction of the “Palace of the People”, which is the second largest building in the world, although it was never completed, and the Centru Civic. In the era of glasnost and perestroika this became more and more unacceptable to both the Soviet Union and the West. In the last years of his rule, Ceaușescu had lost all sense of proportion and all relation to its population. Warning signs of growing discontent among the workers such as the Brașov uprising in 1987 were ignored by Ceaușescu. Since the social elite learned English and French in schools and had the opportunity to get information from the West, the rebellion against the dictatorship grew underground.

Romanian Revolution 1989

Unlike the Soviet Union at the same time, Romania did not develop a comprehensive, privileged elite. Outside of Ceaușescu's own relatives, government officials were often rotated from job to job and relocated to prevent the possibility of developing a power base. This prevented the Gorbachev era reform communism , which existed in Hungary or the Soviet Union. In contrast to Poland, Ceaușescu reacted to strikes with a ruthless strategy of further repression. Those who warned him against such a policy were treated as criminals. When the wave of the 1989 revolution spilled over to Romania, it did so with incomparable energy. The fall of the Romanian regime was almost one of the last in Eastern Europe. He was also one of the most brutal of the time. Although the events of December 1989 are highly controversial, the following account is at least a fair outline.

Protests and riots broke out in Timișoara on December 17th . The trigger was the evacuation from the rectory ordered by the police and the planned arrest of the Protestant pastor and later bishop László Tőkés , who was an outspoken opponent of Ceaușescu. Although the first demonstrators were evacuated by the Securitate, the unrest spread across the city the next day. Soldiers opened fire on the protesters, killing around 100 people. The outrage over the shootings spread to Sibiu, Bucharest and elsewhere. Soldiers outside Timisoara usually refused to carry out orders to attack protesters.

After a two-day trip to Iran, Ceausescu reached out to a handpicked crowd of 100,000 people in central Bucharest on December 21. Even here the crowd started screaming at him. The Securitate opened fire, but Defense Minister Vasile Milea's military generally refused to follow suit . After Milea died under circumstances that were not entirely clear and the loyalty of the army no longer seemed guaranteed, Ceaușescu and his wife Elena Ceaușescu tried to escape from the capital by helicopter. The army and the Securitate fought open street fighting in Bucharest, and hundreds, perhaps thousands, were killed in gunfire. The Ceauşescus were finally arrested in Târgovişte . Her life might have been spared if the Securitate had been willing to lay down their arms; but they were subjected to a swift and dubious trial and shot on December 25th. With her death, the Securitate began to give up and soon broke up, bringing the violence to an end.

Post communist era

1990-1992

Regardless of the controversies described, Romania has made great strides in institutionalizing democratic principles, civil rights and respect for human rights since the revolution. However, the legacy of 44 years of communist rule cannot suddenly be erased. Membership in the Communist Party was usually a prerequisite for higher education, foreign travel or a good job, while the extensive internal security apparatus undermined normal social and political relationships. It must appear to the few active dissidents who suffered under Ceaușescu that most of those who made careers as politicians after the revolution have been compromised by their collaboration with the old regime.

Over 200 new political parties emerged after 1989, revolving more around personalities than programs. All major parties advocated democracy and market reform, but the ruling National Bailout Front (FSN) proposed slower, more cautious economic reforms and a social safety net. In contrast, the main opposition parties - the National Liberal Party PNL and the Christian Democratic Peasant Party PNȚ-CD - favored rapid and radical reforms, immediate privatization, and a weakening of the influence of the ex-communist elite. While there is no law banning communist parties, the old communist party disbanded anyway, but many former party members remained active.

On May 20, 1990, presidential and parliamentary elections were held. Ion Iliescu won 85.07% of the votes against representatives of the National Peasant Party PNȚ-CD and the National Liberal Party PNL , which existed before the war . The FSN (Front of National Rescue) received 66.31% of the vote and received three quarters of the seats in parliament. The strongest opposition parties were the Democratic Alliance of Hungarians in Romania (UDMR) with 7.23% and the PNL with 6.41%. He appointed the university professor Petre Roman as prime minister and began cautious economic reforms.

The new government made a crucial misstep early on. Dissatisfied with the continued political and economic influence of members of the elite of the Ceaușescu era, anti-communist demonstrators met in Bucharest University Square for an ongoing protest . Two months later, miners from the Jiu Valley were brought to Bucharest and brutally dispersed the remaining protesters (" mineriades "). President Iliescu publicly expressed his gratitude, which convinced many that the government had initiated the miners' actions. The miners also attacked the headquarters and homes of opposition leaders. The Roman government fell in late September 1991 when the miners returned to Bucharest to demand higher wages and better living conditions. A technocrat, Theodor Stolojan , was appointed head of an interim government until new elections were held.

Parliament drafted a new democratic constitution , which was adopted in a referendum in December 1991. The FSN split into two groups in March, led by Ion Iliescu (FDSN) and Petre Roman (FSN). Roman's party subsequently adopted the name "Democratic Party" (PD).

1992-1996

The local and national elections in September 1992 revealed a political gap between the major urban centers and the country. The rural voters, grateful for the return of most of the farmland to the farmers but feared changes, preferred President Ion Iliescu and the FDSN, while the urban voters preferred the CDR (an alliance of several parties, including the PNȚ-CD and the PNL were the strongest, and civic organizations) and favored rapid reforms. Iliescu was easily re-elected against five other candidates. The FDSN won a majority in both houses of parliament. The FDSN formed a government in November 1992 under Prime Minister Nicolae Văcăroiu , an economist, with parliamentary support from the nationalist parties PUNR and PRM and the communist PSM. In July 1993 the FDSN became the “Romanian Social Democracy Party” (PDSR). In January 1994 the stability of the governing coalition was jeopardized by the threat of the PUNR withdrawing its support if it did not get a position in the cabinet. In August 1994, two members of the nationalist PUNR were given cabinet posts in the government. In September the incumbent Justice Minister announced that he had joined the PUNR. The PRM and PSM left the government in October and December 1995, respectively.

1996-2000

The local elections of 1996 resulted in a major shift in the political orientation of Romanian voters. The opposition parties prevailed in Bucharest and in most of the larger cities in Transylvania and the Banat .

The trend continued in the national elections, with the opposition dominating the cities and winning strongly in the rural areas and the former strongholds outside of Transylvania, which had previously been dominated by Iliescu and the PDSR. The opposition's campaign focused on the two issues of anti-corruption and economic reform. This message was echoed by the electorate, and Emil Constantinescu and his allied parties came to power.

Emil Constantinescu from the “Democratic Convention of Romania” (CDR), an electoral alliance, defeated President Iliescu by a margin of 9% in the next election and became the new head of state.

The PDSR won the largest number of seats in parliament, but the parties of the CDR, the Democratic Party, the PNL and the Democratic Union of Hungarians of Romania (UDMR) together formed a center coalition government with 60% of the seats in parliament would have. Victor Ciorbea became prime minister. Ciorbea remained in office until March 1998 and was first replaced by Radu Vasile ( PNȚ-CD ), then by the head of the National Bank Mugur Isărescu .

The multi-party coalition turned out to be not always easy, as decisions were often delayed by lengthy negotiations. Nonetheless, several crucial reforms have been initiated. The influence of former communists and members of the "Securitate" in the state administration was eliminated and a functioning market economy was introduced.

The coalition government formed in December 1996 took a historic step by inviting the UDMR and its Hungarian supporters into the government.

In July 2000, President Emil Constantinescu announced that he would no longer run.

2000-2004

In the parliamentary elections in November 2000, the Christian Democratic PNȚ-CD failed at the electoral hurdle, the liberal PNL and the Democratic Party formed the actual opposition in Romania. The PSD (Party of Democratic Socialism) under Ion Iliescu recorded an impressive victory. Adrian Năstase became Prime Minister of the government that was shaken by several corruption allegations in 2003. In October 2003, three ministers had to resign on these allegations.

The EU accession process continued. Democratic transparency, corruption and the handling of press freedom were problematic in Romania under Iliescu and Năstase.

In 2002 Romania was invited to join NATO in 2004 . This accession took place in the course of NATO's eastward expansion on March 29, 2004. In the same year, the European Union confirmed its support for Romania's goal of joining the Union in 2007. However, this required profound changes in the economy in the years that followed.

2004-2008

Presidential elections were held on November 28 and December 12, 2004 . The two most important candidates were the incumbent Prime Minister Adrian Năstase from the PSD and the mayor of Bucharest, Traian Băsescu, from the liberal alliance DA. While Năstase insisted on the continuity of his government, which was already plagued by corruption scandals, Băsescu was now promoting the fight against corruption.

Traian Băsescu won the race and named Călin Popescu-Tăriceanu from the liberal alliance DA as prime minister.

The bicameral parliament was also re-elected on November 28, 2004. The largest parliamentary group was formed by the PNL and PD , which formed a center-right government with the PUR and UDMR, which primarily wanted to fight corruption and implement reforms in agriculture and industry.

On April 13, 2005, the European Parliament in Strasbourg approved Romania's accession to the European Union. Romania and Bulgaria have been members of the EU since January 1, 2007.

The PNL-PD alliance broke up in 2007; Tăriceanu continued to rule with a largely incapable minority government made up of PNL and UDMR.

2008-2011

The parliamentary elections in Romania in 2008 were for the first time decoupled from the presidential elections. The PSD and the newly founded PD-L emerged victorious, after which they formed a government under Emil Boc . Tough austerity measures sparked protests and ultimately a vote of no confidence in parliament. The Boc II cabinet resigned. Former Foreign Minister Teodor Baconschi claimed that manipulation of individual MPs had caused some to join the opposition alliance. In early February 2012, President Traian Băsescu appointed Mihai Răzvan Ungureanu as Prime Minister and entrusted him with forming a government.

State crises in Romania since 2012

After less than three months in office, Ungureanu's government failed due to a successful vote of no confidence in parliament, which was tabled by the Partidul Social Democrat (PSD) and Partidul National Liberal (PNL) parties .

Strengthened by defectors, the National Liberal Party ( Romanian Partidul Național Liberal , PNL), the Social Democratic Party ( Partidul Social Democrat , PSD) and the Conservative Party ( Partidul Conservator , PC) joined the new government alliance Social Liberal Union ( Uniunea Social Liberală , USL) ) under Prime Minister Victor Ponta . The declared goal was the disempowerment of Romanian President Traian Băsescu from the Democratic Liberal Party ( Partidul Democrat Liberal , PD-L). At the end of June 2012, impeachment proceedings against Băsescu were initiated. The vote in parliament led to the president's suspension. The official business is conducted by the national liberal Senate President Crin Antonescu . In the popular vote ( referendum ) on 29 July 2012 on the impeachment Băsescu, his accusations were made about massive constitutional violations in the run-up to, much of the population had to have chosen the overwhelming feeling, the lesser evil, even if it is after the open call the PD-L abstained from voting on the election boycott. The turnout was below the required 50 percent of possible votes and was declared invalid. Of the votes cast, around 87 percent opted for impeachment. The USL expressed doubts about the correctness of the electoral roll on which the referendum was based and appealed to the Constitutional Court of Romania . This announced that it would decide on the validity of the referendum on August 21, after it was presented.

The USL's political approach, often described by critics as a “ coup d'état ”, drew fierce national and international criticism. In addition to the widespread corruption in Romania, the background is a power struggle between political cliques from the various camps, which is not always in accordance with the principles of the law. In Romania's corrupt political world, unease grew when a former PSD prime minister was sentenced to several years in prison.

World politics expressed concern about the pressure on constitutional judges and the rule of law that it harassed , arbitrary governance through emergency ordinances, and a lack of interest in the values of the European Union (EU). The chief justices reported tremendous pressure from the government, including threats against their families. The EU expressed its determination to guarantee the independence of the judiciary in Romania.

In the 2014 presidential elections , Klaus Johannis , the mayor of Sibiu , was elected Băsescu's successor. He prevailed in a runoff election against Prime Minister Ponta.