History of the Jews in Romania

The history of the Jews in Romania begins according to archaeological finds at the time of the Roman Empire . Written traditions have existed since the early Middle Ages .

After the formation of the united principality of Romania in 1859, efforts to enforce constitutional equality for Jews met with massive opposition, initially within and outside of parliament. On the other hand, there were new opportunities. In 1876, the first Yiddish theater in Europe was founded in Iași.

The Jews were formally granted rights after the intervention of the Berlin Congress in 1878, but these were practically worthless, as most Jews were denied Romanian citizenship. In 1881 the first Zionist organization worldwide was established in the Kingdom of Romania .

After the First World War , the legal position of the Jews improved; they could take part in social, cultural and political life with some restrictions. With the change of government in 1937, anti-Semitism was openly declared a state policy.

During the Second World War , around 350,000 Jews were killed under the Romanian dictator Ion Antonescu in cooperation with the Nazi regime. The systematic persecution of Jews gradually declined from the summer of 1942 and ended with the fall of Antonescu on August 23, 1944. In the post-war period and during the rule of the Communist Party, most Jews emigrated to Israel and the USA . In the 1990s, a controversial public reappraisal of the Romanian participation in the Holocaust began hesitantly .

Beginnings

Little is known about the early Jewish settlement of today's Romania after the turn of the century . It is possible that Jewish settlements still existed on the Black Sea coast of Dobruja during the time of the Roman Empire from the 2nd to the 4th century AD . H. in the Roman province of Moesia inferior (Lower Moesia ). At the beginning of the 2nd century Jews first came to the province of Dacia (Dacia) as Roman legionaries and later as traders . Tomb inscriptions and coin finds testify to this, including an item from the time of Bar-Kochba (133 AD). Nothing is known about a possible continuity of Jewish life between antiquity and the Middle Ages in the region. Presumably the Jewish culture of Dacia perished during the time of the Great Migration .

In the Danube principalities

The term " Danube Principalities " includes Wallachia and Moldova , which were the forerunners of the Romanian state that was constituted in 1859/62. Overall, the Jews in Moldova were represented much more numerous, their living conditions better than in Wallachia. For 1848 approx. 60,000 Jews were accepted in Moldova, compared to approx. 6000 in Wallachia.

Principality of Wallachia

Already during the early days of the Principality of Wallachia, especially under Prince Vladislav I , Jews immigrated there who had to flee from the Kingdom of Hungary during the reign of Ludwig I (1342-1382) . From the time of Vlad III. Drăculea (1456–1462) reports of persecution of Jews. Prince Mihai Viteazul ordered a mass execution in 1594, which also killed many Jews. This measure was probably not directed explicitly against Jews, but against all foreign creditors. As a result, phases of extensive tolerance alternated with sections of rather less pronounced persecutions. Prince Matei Basarab tried in 1633 to convert the Jews of Wallachia to Christianity by giving converts important offices. Constantin Brâncoveanu granted the Jews some privileges. His successor Ștefan Cantacuzino had the Bucharest synagogue destroyed. In the 18th century, anti-Semitic literature was initially founded on religion. In it, the Jews were repeatedly accused of ritual child murder, so that in 1804 Prince Constantin Ipsilanti felt compelled to call the Orthodox clergy to order. In 1812 - during the Russo-Turkish War - Kalmuck troops looted the capital Bucharest, destroying the Jewish quarter in particular and killing numerous Jewish residents. Two years later there was a pogrom in the city , which killed 128 Jewish residents.

Principality of Moldova

Even before the founding of the Principality of Moldova, Jews settled in the cities of Bârlad and Galați . Later, the resident Jews and the newly immigrated Jews received extensive concessions from the rulers Petru Musat (1391–1394) and Alexandru cel Bun (1400–1432). Ștefan cel Mare (1457–1504) brought with him Jewish prisoners from his successful campaigns against Poland , who, like a large number of voluntary Jewish settlers from Poland, settled in Moldova. Also in the 16th and 17th centuries other Jews - again mainly from Poland - immigrated to Moldova, especially during the anti - Jewish uprisings under Bohdan Khmelnyzkyj (1648–1657). At the beginning of the 18th century, numerous cities in the Moldavia were already inhabited by Jews. Local nobles called more Jews into the country in order to repopulate regions devastated by war and disease and to found new cities. Most of the Jews worked as artisans, traders and innkeepers. In a census in 1793, Moldova registered 4,000 Jewish taxpayers, which is likely to correspond to around 25,000 inhabitants. From the end of the 18th century, many Jews came from neighboring Galicia , which was under Austrian rule, to avoid military service, as well as from Russia . At that time, the economic conditions in Moldova were probably better than in Galicia and Russia. In 1859 Galai was charged with an alleged ritual murder ; however, the accused were acquitted.

In united Romania

The question of how to deal with the Jewish minority has preoccupied the representatives of the Romanian state people since the beginning of the unification process. During the revolutionary events of 1848 , the Romanian national and liberal forces demanded equality for Jews; However, their representatives who later assumed government responsibility mostly pursued a repressive policy. The Jews were accused of failing to assimilate, of dominating the trade like a monopoly and, as innkeepers, of harming the Romanian farmers by selling alcohol.

In 1859 the Principality of Romania was formed from the Principality of Moldavia and Wallachia. Iași became the capital. Prime Minister Ion C. Brătianu first tried in 1867 to enforce constitutional equality for Jews, but met with massive opposition within and outside of parliament. A synagogue was destroyed in Bucharest, and riots broke out in Iași and numerous other cities on the Vltava. In Galați soldiers threw 18 Jews into the Danube , two of whom drowned. In order not to lose his political backing, Brătianu gave up the project of equal rights for Jews and issued several regulations prohibiting Jews from living in rural communities, leasing land, or becoming innkeepers or innkeepers. The pogrom-like excesses and the repressive legislation prompted major European powers to intervene diplomatically, which briefly led to an end to the unrest. But as early as April 1868, the Jewish cemetery in Bacau was desecrated and 500 families were evicted after their houses were set on fire. After renewed international attention, there was a phase of relative calm - apart from locally limited riots from 1870 to 1872 - but the statutory circumcisions of the Jews remained in force. The Ottoman Empire , still formally the suzerain of the Romanian principality, asked the Romanian cabinet in vain to protect the rights of the Jews. The prince and later King Carol I took only half-hearted measures against the legislative and other grievances. On the other hand, Brătianu prevented further anti-Semitic bills that were introduced by Romanian nationalists in Moldova.

The fundamentally changed situation meant that immigration, which was quite brisk until around 1860, came to a complete standstill.

In 1876 the first Yiddish theater was founded in Iași by Abraham Goldfaden . This year, for the first time, Yiddish theater performances were also held in Bucharest.

In 1878 Romania became independent from the Ottoman Empire. The Berlin Congress in 1878 demanded that the Jews be granted constitutionally normal civil rights; after some resistance, this was implemented by the Romanian parliament. Legislation no longer excluded Jews from certain rights. In practice, however, the Jews continued to see themselves at a considerable disadvantage: Jews were called up for military service, but were not allowed to rise to the ranks of officers; Jewish children were partially prevented from attending school, and their access to secondary schools was increasingly difficult. As a rule, Jews were not allowed to practice several academic professions (doctor, judge). The status of many Jews as "foreigners" served as the legal basis; the "naturalization" - d. H. the granting of citizenship rights - was handled very slowly and restrictively. This also made it possible to expel critical Jewish journalists from the country. By 1916 only 883 Jewish soldiers who had fought in the War of Independence in 1877/78 , as well as a few hundred other Jews, had been naturalized. In addition to the legal, rather indirect measures against Jews, some communities decreed unlawful reprisals against Jews (mostly arbitrary levying of taxes) that were tolerated by the higher authorities. Riots against Jews that flared up again and again usually had no legal consequences for the perpetrators.

In 1881 Chibbat Zion , the very first Zionist organization, was established with its headquarters in Galați.

In a census in 1889, 266,652 Romanians identified themselves as Jews; thus the proportion of the total population was 4.5 percent.

In 1895 an "Anti-Semitic Alliance" ( Romanian Alianța Antisemită ) was founded in Bucharest , which several politicians were close to and which advocated a further tightening of the measures directed against Jews.

In 1900 there was a great wave of Jews emigrating from Romania; most of them went to the US. Some of them escaped on foot as so-called Fusgeyer . The Romanian authorities soon noticed that this was causing severe economic disadvantages, especially in Moldova; the originally welcome emigration was prohibited. From the founding of Romania to the outbreak of the First World War , a total of over 70,000 Jews left the country.

In February and March 1907 there was a great peasant uprising , especially in the Moldavia , which was justified by the great need of the Romanian peasants, but also had anti-Semitic features. Most Jews were not allowed to own land as “foreigners”, but acted as interim tenants for the big landowners - the boyars - who on behalf of the boyars leased the land to poor farmers for usurious interest and in some cases made considerable wealth themselves. These Jews were particularly hated by the peasants. The rioting against Jews was initially tolerated by the Romanian authorities; However, as the uprising quickly turned against the government and threatened the stability of the state, it was brutally suppressed by the army.

Around 30,000 Jews fought in the Romanian army during World War I , although the vast majority of them still did not hold citizenship.

Greater Romania

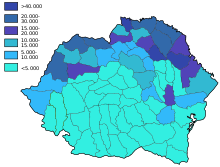

After the First World War, Romania was granted large areas, including in the Treaty of Trianon , which more than doubled its territory and also the number of Jews. The total population increased from 7.5 to 16 million, the number of Jews to almost 800,000. Of these, around 230,000 lived in the original national territory, 240,000 in Bessarabia , 130,000 in Bukovina and 200,000 in the former Hungarian areas ( Transylvania , Banat , Kreischgebiet , Sathmar , Maramures ). The area gains were made on the condition that Jews and other national minorities were granted full civil rights. The implementation of this requirement was not without controversy in the politically relevant circles of the country; Prime Minister Ion IC Brătianu resigned in 1919 because he did not want to support collective equality for Jews.

In 1923 a new constitution was passed, followed by several laws that allowed the Jews of Romania to acquire citizenship. The Jews could now participate in the social, political and cultural life of the country. In 1932, a Jewish party succeeded in sending five members to the Romanian parliament. Access to state schools was largely unhindered; there were also numerous Jewish schools in which teaching in Yiddish or Hebrew could be given. However, the Jews were denied higher posts in state administration, higher military ranks and university professorships.

In the late 1920s, the Iron Guard , a far-right organization, gained increasing influence over political life and became a mass movement. Their leader Corneliu Zelea Codreanu was able to get a significant part of the rural population, especially the middle classes and students, behind them, especially with anti-Semitic theses. The increasing political instability also made the situation of the Jews worse.

At the end of 1937, Octavian Goga formed a government in which Alexandru C. Cuza from the National Christian Defense League ( Liga Apărării Național Creştine ) also participated. Anti-Semitism was openly declared a state policy. On January 22, 1938, a law was passed on the basis of which 36 percent of the Jews were revoked their citizenship. As in National Socialist Germany, numerous academic professions removed Jews from their professional bodies.

In February 1938 a royal dictatorship began under Carol II . Jews were no longer allowed to serve in the army, but had to pay a high transfer fee. Marriages between Christians and Jews were forbidden. Romania came increasingly into economic and political dependence on the Third Reich . In 1940 Romania had to cede Bessarabia and the north of Bukovina to the Soviet Union as a result of the Hitler-Stalin Pact . Romanian soldiers murdered numerous Jews on their retreat from these areas.

After the Second Vienna Arbitration in 1940, General Ion Antonescu forced Carol II to resign and in turn ruled with dictatorial powers. Initially, members of the Iron Guard also took part in the government under their current leader, Horia Sima ; there were numerous violent riots against Jews. From January 21 to 23, 1941, the Iron Guard staged an attempted coup in order to gain complete control of the government. In the course of these events, a pogrom broke out in Bucharest that killed 120 people. In addition, 25 synagogues were destroyed, 600 Jewish shops and the same number of Jewish homes looted. In the power struggle, Antonescu prevailed against the Iron Guard, but this did nothing to change the increasingly anti-Jewish style of government. Jewish land and real estate was expropriated, Jews were banned from attending state schools, and all Jewish state employees were dismissed.

Romania and the Holocaust

On June 21, 1941, one day before the attack on the Soviet Union and Romania's entry into the war on the German side, Marshal Antonescu ordered all Jews from rural regions to be deported to cities . Almost all adult Jewish men were drawn into compulsory labor. Much of the privately owned Jewish property was expropriated; the same applied to the properties of the Jewish communities. All Jewish state employees were fired, as were many private workers. Numerous Jewish merchants were driven to ruin by specially enacted laws and regulations.

On June 29, 1941, a few days after the attack began, soldiers of the German Wehrmacht, together with Romanian military and police units, secret service employees and members of the civilian population , murdered around 13,000 Jews in the Iași pogrom .

In a few weeks Romanian troops recaptured the territories of Northern Bukovina and Bessarabia , which had been lost to the Soviet Union a year earlier , which brought numerous other Jews back into Antonescu's sphere of influence. The reclaimed areas were placed under a special regime, which was supposed to enable the ethnic cleansing to take place undisturbed.

At the beginning of July 1941, Antonescu announced before the Council of Ministers a comprehensive “cleansing” of the Romanian people from “elements alien to the people” and demanded merciless action against the Jews of the recaptured areas. On July 12, 1941, he ordered the authorities of Bessarabia and Bukovina to immediately begin "cleaning up the land" ( Romanian Curăţirea terenului ). This euphemistic word creation stood for the Holocaust in Romania, analogous to the expression “ final solution to the Jewish question ” in the language of National Socialism .

The extent of physical persecution in Romania varied widely from region to region. The Romanian leadership assumed that the Jews of Bessarabia and northern Bukovina had sympathized with the Soviet Union. Almost all Jews from these areas were deported to camps set up for this purpose in Bessarabia from July 1941 (including Chișinău , Vertiujeni near Floreşti , Mărculeşti , Edineț , Secureni ) and on to Transnistria until October . A short time later this measure was extended to many Jews in southern Bukovina. The Jews in the other parts of the country ( Moldova , Wallachia , Dobruja , Banat , southern Transylvania , southern Kreischgebiet ) were usually not deported; Exceptions were Jews who were “communist”, who stayed away from compulsory work, and “speculators”.

Many of the deportees died of disease and starvation in the Transnistrian camps and on the way there. In addition, there were repeated mass shootings. Of the 190,000 inmates, around 50,000 were still alive when the Red Army arrived .

From September 9, 1941, the Jews of eastern Romania were deported to the Transnistrian governorate . Task Force D of the Security Police and SD and Romanian soldiers set up by the Nazi regime together murdered more than 115,000 Ukrainian Jews there. The local population took part because they were allowed to appropriate the property of those who were shot. Tens of thousands of other deported Jews died in makeshift camps along the Dniester of malnutrition and hunger.

In 1942, 25,000 Roma were deported to Transnistria, of whom between 11,000 and 19,000 died there. Antonescu also commissioned General Vasiliu with this deportation. He described his task as “collecting and removing the fur of stray dogs”.

Starting in the summer of 1942, Antonescu promised the Nazi regime in writing that he would also hand over the Jews of Old Romania for extermination. For reasons of tactical power, this contract was not implemented. In contrast to Germany and its sphere of influence, where Hitler, with the increasingly unfavorable military situation, pushed the extermination of the Jews more and more, the persecution in Romania subsided from 1942. The planned deportation of the Jews concentrated in the Romanian cities to Transnistria did not take place to a large extent. The promise, hoped for by the Germans and already given in principle by Ion Antonescu, to extradite the Jews of Romania to Germany was not implemented either. In July 1942, Adolf Eichmann assumed that deliveries would begin around September 10, 1942. The SS-Sturmbannführer Gustav Richter was to organize these measures. Antonescu repeatedly postponed the deportations and finally canceled them entirely. Historians assume that the reasons are interventions from neutral third countries. The Antonescus family is also said to have been bribed by wealthy Jews. Antonescu also feared punitive measures by the Allies in the event of Romania's military defeat.

In 2004 the Wiesel Commission came to the conclusion that under the responsibility and as a result of the deliberate policy of the Romanian military and civil authorities, 280,000 to 300,000 Jews were murdered or died, including numerous Ukrainian Jews who killed Romanian occupation soldiers during the war. In Transnistria, in addition to the deportees, 105,000 to 180,000 Jews living there were also killed, especially in Odessa , where 25,000 to 30,000 Jews were killed within a few days.

Northern Transylvania , Maramures , the Sathmar region and the northern Kreisch area represent a special case . These areas did not belong to Romania during the war, but to Hungary as a result of the Second Vienna Arbitration . The Jews resident there were taken to the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp and the other extermination camps of the General Government in 1944 and murdered. Of the original 130,000 Jews in these areas, only around 10,000 survived.

The total number of victims can only be estimated approximately. In particular, the number of those killed by Romanian firing squads in Transnistria is unclear. The post-war turmoil throughout Europe also made it difficult to record the survivors. The Holocaust researcher Dieter Pohl estimates that under Antonescu's government around 350,000 Jews were murdered in areas of Greater Romania by the summer of 1942.

The systematic persecution of Jews in Romania ended with the fall of Ion Antonescu on August 23, 1944 by King Mihai I and the occupation of the country by the Red Army. Constantin Vasiliu and Mihai Antonescu were executed on June 1, 1946 for the 1941 mass murders and other crimes.

The Israeli memorial Yad Vashem has 60 Romanians , the Jewish risking their lives fellows who helped during the Holocaust, the title of Righteous Among the Nations awarded.

The post-war period and the rule of the Communist Party until 1989

After the fall of Ion Antonescu, around 285,000 Jews lived on the territory of Romania - to which northern Bukovina and Bessarabia again no longer belonged. Their number rose to around 390,000 by 1946 due to the return of the surviving deportees and immigration from other Eastern European countries.

Immediately after the end of the Second World War, most Jews were under the impression of the traumatic experiences of disenfranchisement and physical persecution. In addition, a large number of them lived in great poverty as a result of previous expropriations and high unemployment. Many were dependent on the support of foreign Jewish organizations. Therefore, most of the Jews of Romania wanted to leave the country. Most of them wanted to leave for Palestine . A complex Zionist movement with numerous groups emerged.

This phase was accompanied by a constantly changing political constellation. After the fall of Antonescu, a bourgeois all-party government including the communists took power. With the support of the Soviet Union , the latter succeeded in expanding their influence further and in 1947/48 to obtain complete control over the country's politics .

The anti-Jewish laws were repealed in the first months after the war. Numerous schools and high schools were able to open, in which Yiddish was taught. The return of the expropriated property was only incomplete and hesitant. Also because of the poor economic situation in Romania, which had to transfer large parts of its state budget to the Soviet Union as reparations , reintegration into working life was difficult. Financial reparation was only rudimentary. But the ongoing anti-Semitism of large sections of the Romanian population also prevented the Romanian government from supporting the Jewish minority.

The leader of the Romanian Jews in the interwar period , Wilhelm Filderman , was arrested in 1945 and was able to flee the country in 1948. The Secretary General of the Romanian Communist Party (PCR) called while participating in a gathering of Jewish organizations in Romania on 22 April 1946, the formation of a new association, the so-called Jewish Democratic Committee , as a subset of PCR. However, this attempt to bring the Jewish minority into line was hardly successful.

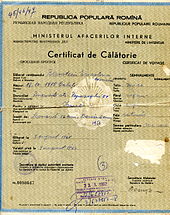

The emigration of Jews was initially tolerated (in some cases even encouraged) by the Romanian government in the first post-war years and was rather limited by the restriction of immigration by the British occupying forces in Palestine . The communist government, which was heavily dependent on the Soviet Union, tried to curb emigration from 1948 - when relations between the Soviet Union and the newly founded Israel deteriorated dramatically.

The first major wave of emigration came in 1950/51 when Romania agreed to release a larger number of Jews in return for economic benefits. For example, oil production systems were delivered to Romania from Israel. In return, 85,000 Jews were able to leave the country. Both countries also agreed to allow 5000 Jews to emigrate every month. The Joint Distribution Committee assumed the costs of 8,000 lei per capita to be paid to Romania . A total of 118,000 Jews left the country for Israel between May 1948 and the end of 1951. As a further compensation, poultry farms and other agricultural businesses were supplied by Israel.

The Romanian government's anti-Zionist propaganda continued, however; the Jews still in the country were promised that they would expect a better life in socialist Romania than in capitalist Israel. This agitation was not very successful; After a temporary repression of emigration, between 1956 and 1964 the government allowed most Romanian Jews who so wished to leave the country. In addition to Israel, many Jews went to the United States.

During the rule of the Communist Party, a total of between 300,000 and 350,000 Jewish people left the country. At the last census before the revolution in 1989 , 24,667 Romanian citizens identified themselves as Jews.

Under the rule of Nicolae Ceaușescu , anti-Semitism became, to some extent, part of national communist ideology. In the 1980s, corresponding newspaper articles were also tolerated. On the other hand, Romania was the only country in Eastern Europe to maintain diplomatic relations with Israel even after the 1967 Six Day War .

After the Romanian Revolution

After the fall of Ceaușescu in December 1989, the few remaining Jews left the country; In 2002, 5,870 people in Romania claimed to be Jewish, and 6,179 to be Jewish. The number of religious communities decreased from 67 in 1990 to 33 in 2002.

Since the beginning of the 1990s, a hesitant public discussion and an appraisal of the Romanian participation in the Holocaust began . This turned out to be quite contradictory. Until after 2000, Ion Antonescu's image was largely positive in the media. In 1991 the Romanian parliament remembered him with a minute's silence, and numerous streets were named after him. It was often claimed (as shortly after the war) that Antonescu did not persecute the Jews, but saved them by preventing them from being extradited to Hitler's Germany. Some Romanians also held Jews responsible for establishing the rule of the Communist Party; Confirmation of this thesis was seen in the fact that, before and immediately after the Second World War, Jews were clearly over-represented within the (numerically very small) Communist Party, but also in the Securitate secret service, compared to the proportion of the total population.

Anti-Semitism found its main form of political expression in post-communist Romania through the appearance and success of the Greater Romania party of Corneliu Vadim Tudor . The avowed Antonescu and Ceaușescu supporters blamed the Jews in particular, but also Hungarians and Roma, for all negative aspects in recent Romanian history. In the 2000 Romanian presidential elections , Tudor received 33% of the vote in the second ballot. In 2004 he announced his change from anti-Semitic to Philosemite , which he explained with a religious experience.

In July 2003 the Romanian President Ion Iliescu and the Romanian Minister of Culture at the time played down the Holocaust in their declarations and thus nurtured the belief that the Holocaust did not take place in Romania. After an international outcry over these statements, Iliescu convened the Wiesel Commission headed by Nobel Peace Prize laureate Elie Wiesel in October 2003 to investigate the Holocaust in Romania on the basis of the latest historical findings. The Commission presented its final report at the end of 2004. The Romanian government recognized the results of the final report and admitted that Romania deliberately participated in the Holocaust during the Second World War under the regime of Ion Antonescu. The report of the Wiesel Commission documents, among other things, the widespread anti-Semitism in Romania before the Second World War.

Romania celebrated Holocaust Day for the first time on October 9, 2004 ( Romanian Ziua Holocaustului ). On the occasion, President Ion Iliescu expressed general mourning over "250,000 Jews killed in territories under Romanian administration". On October 9, 2006, the foundation stone was laid for a memorial by President Traian Băsescu , which was designed by the Transylvanian-Saxon sculptor Peter Jacobi and inaugurated by Băsescu in October 2009.

Because of the small number of Jews in Romania, Jewish culture no longer plays a major role. Synagogues still exist in numerous cities, some of which are listed.

There is a Jewish theater in Bucharest. Hasefer publisher publishes books on Judaism in several languages. The magazine Realitatea Evreiască (“The Jewish Reality”) is published in Hebrew every several weeks .

The Federația Comunităților Evreieşti din România (Federation of Romanian Jewish Communities) party, founded in 1997, received 22,393 votes in the 2008 parliamentary elections , significantly more than the country's professing Judaism. One member of this party is now represented in the Romanian Chamber of Deputies .

Well-known Romanians with Jewish roots

Romania is the birthplace of many well-known personalities with Jewish roots. These include the author Felix Aderca , the intelligence officer Vera Atkins , the resistance fighter Olga Bancic , the painters Victor Brauner and Reuven Rubin , the chemist Lazăr Edeleanu , the poet Benjamin Fondane , the writer Mihail Sebastian , the lawyer and historian Serge Klarsfeld , the doctor and Psychiatrist Jacob Levy Moreno , the rabbi and father of conservative Judaism Solomon Schechter , the psychologist Serge Moscovici , the politician Ana Pauker , the actor Edward G. Robinson , the writer Tristan Tzara , the actor Mircea Krishan , the psychologist David Wechsler and the writer Elie Weasel . The parents of the American singer Art Garfunkel and the politicians Michael Howard (United Kingdom) and Jean-François Copé (France) were Romanian Jews.

See also

- Bricha

- History of the Jews in Hungary

- Iasi pogrom

- Judaism in Timișoara

- Struma (ship)

- List of Jewish cemeteries in Romania

literature

- Raphael Vago (Ed.): The history of the Jews in Romania. 4 volumes, Tel Aviv University: The Goldstein-Goren Diaspora Research Center, 2005/2006 (from the Hebrew; authors: Paul Cernovodeanu, Liviu Rotman, Carol Iancu, Raphael Vago, Judy Krausz, Haim Watzman).

History of the Jews in Romania up to the early 20th century

- Johann Daniel Ferdinand Neigebaur : The Jews in Moldavia and Wallachia. In: Heinrich Müller Malten (Hrsg.): Latest world customer. Volume 1, Heinrich Ludwig Brönner, Frankfurt am Main 1848, pp. 250-262.

- Bernard Lazare : The Jews in Romania. HS Hermann, Berlin 1902.

- Beate Welter: The Romanian Government's Jewish Policy 1866–1888. Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main 1989, ISBN 3-631-40490-5 .

- Friedrich Battenberg: The European Age of the Jews - To the development of a minority in the non-Jewish environment of Europe. Volume 2: From 1650 to 1945. 2nd edition. Darmstadt 2000, pp. 250–257: Progress towards emancipation in Europe as a whole, especially development in Eastern and Southeastern Europe.

- Victor Rusu: Back then in the shtetl - Jewish life in Romania. Experienced and handed down stories. Hartung-Gorre, Konstanz 2001, ISBN 3-89649-671-9 .

- Ladislau Gyémánt: The Jews in Transylvania up to the 18th century. In: Volker Leppin, Ulrich A. Wien (ed.): Confession formation and confessional culture in Transylvania in the early modern period. Franz Steiner, Wiesbaden 2005, pp. 191-200.

- Mariana Hausleitner : Germans and Jews in Bessarabia 1814–1941. On the minority policy of Russia and Greater Romania. Institute for German Culture and History of Southeast Europe (IKGS), Munich 2005, ISBN 3-9808883-8-X .

- Mariana Hausleitner : Iași. In: Dan Diner (Ed.): Encyclopedia of Jewish History and Culture (EJGK). Volume 3: He-Lu. Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar 2012, ISBN 978-3-476-02503-6 , pp. 106–112.

- Joachim F. Cotaru: The demand for the granting of citizenship for the Jewish population of Romania in the Bucharest Peace Treaty in 1918. Master's thesis, Hagen 2012 ( PDF file: 674 kB; 114 pages, slightly corrected version from April 2013).

Anti-Semitism and the Holocaust

- Documents

- Institutul Național pentru Studierea Holocaustului din România "Elie Wiesel" (Ed.): Pogromul de la Iași (June 28-30, 1941). Prologul Holocaustului din România. Iași 2006 ( PDF file ( memento from July 23, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) on inshr-ew.ro ).

- Final report: Comisia internaţionalăpentru studierea holocaustului în România: Raport final. Iasi 2005.

- International Commission on the Holocaust in Romania (Ed.): Final Report of the International Commission on the Holocaust in Romania. Bucharest 2004.

- research

- Hildrun Glass: Germany and the persecution of the Jews in the Romanian sphere of influence 1940–1944. Oldenbourg, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-486-72293-2 .

- Simon Geissbühler: Bloody July - Romania's war of extermination and the forgotten mass murder of the Jews in 1941. Schöningh, Paderborn 2013, ISBN 978-3-506-77675-4 .

- Benjamin Grilj (Ed.): Black Milk - Letters withheld from the Transnistrian death camps. Studies Verlag, Innsbruck 2013, ISBN 978-3-7065-5197-7 .

- Jill Culiner: Fusgeyer . In: Dan Diner (Ed.): Encyclopedia of Jewish History and Culture (EJGK). Volume 2: Co-Ha. Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar 2012, ISBN 978-3-476-02502-9 , pp. 393-396.

- Egon Balas : The Will to Freedom - A Dangerous Journey through Fascism and Communism. Springer, Berlin 2011, ISBN 978-3-642-23920-5 (pp. 57–162 on the persecution of Jews from 1941 to 1944 and anti-Semitism in the post-war period).

- Mariana Hausleitner: The confrontation with the Holocaust in Romania. In: Micha Brumlik, Karol Sauerland (Hrsg.): Re-interpret, keep silent, remember - the late coming to terms with the Holocaust in Eastern Europe. Campus, Frankfurt am Main 2010, ISBN 978-3-593-39271-4 , pp. 71-89.

- Andrei Oişteanu : Constructions of the image of the Jews - Romanian and East Central European stereotypes of anti-Semitism. Frank and Timme, Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-86596-273-7 .

- Brigitte Mihok (ed.): Holocaust on the periphery - Jewish policy and the murder of Jews in Romania and Transnistria 1940–1944. Metropol, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-940938-34-3 .

- Siegfried Jägendorf: The miracle of Moghilev - the rescue of ten thousand Jews from the Romanian Holocaust. Transit, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-88747-241-2 .

- Armin Heinen : Romania, the Holocaust and the logic of violence. Oldenbourg, Munich 2007, ISBN 3-486-58348-4 .

- Saul Friedländer , Martin Pfeiffer: The Third Reich and the Jews: The Years of Destruction, 1939–1945. Beck, Munich 2006, ISBN 978-3-406-56681-3 .

- Andrej Angrick: Occupation Policy and Mass Murder: The Einsatzgruppe D in the southern Soviet Union 1941-1943. Hamburger Edition, Hamburg 2003, ISBN 3-930908-91-3 .

- Mariana Hausleitner (Ed.): Romania and the Holocaust - On the mass crimes in Transnistria 1941–1944. Metropol, Berlin 2001, ISBN 3-932482-43-3 .

- Mariana Hausleitner: The Romanization of Bukovina. Oldenbourg, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-486-56585-0

- Mariana Hausleitner, Viorel Achim: The Romanian Population Exchange Project Elaborated by Sabin Manuila in October 1941. In: Yearbook of the Italian-German historical institute in Trieste. Volume 27, 2001, pp. 593-617 (English).

- Radu Ioanid: The Holocaust in Romania, the Destruction of Jews and Gypsies Under the Antonescu Regime 1940-1944. Dee, Chicago 1999, ISBN 1-56663-256-0 (preface by Elie Wiesel , introduction by Paul A. Shapiro ).

- Rainer Ohliger: From a multi-ethnic state to a nation-state - migration from and to Romania in the 20th century. In: Heinz Fassmann, Rainer Münz (Ed.): Migration in Europe. Campus, Frankfurt am Main 1996, ISBN 3-593-35609-0 , pp. 285-302.

- Alexandre Safran : "Torn from the Flames". The Jewish Community in Romania 1939–1947. Memories. A. Francke, Tübingen 1995, ISBN 3-7720-2148-4 .

- Mirjam Korber: Deported. Jewish survival fates from Romania 1941–1944. A diary. With a family story by Sylvia Hoisie-Korber and an account of the 1941 massacre in Jassy by Henry L. Eaton. Hartung-Gorre, Konstanz 1993, ISBN 3-89191-617-5 .

- Claus Stephani : "Was a ruler, carter". Life and suffering of the Jews in Oberwischau. Reminder conversations. Athenäums, Frankfurt am Main 1991, ISBN 3-445-08562-5 .

History of the Jews in Romania after 1945

- Hildrun Glass: Minority between two dictatorships - On the history of the Jews in Romania 1944–1949. Oldenbourg, Munich 2002.

- Hildrun Glass: The Disappearance of a Minority - The Emigration of the Jews from Romania after 1944. In: Konrad Clewing, Oliver Jens Schmitt (Ed.): Südosteuropa. Festschrift for Edgar Hösch. Oldenbourg, Munich 2005, ISBN 978-3-486-57888-1 , pp. 383-408.

Web links

- Homepage: Romanian Jewish Community. 2003–2012 (English).

- Weblink Collection: Romania During The Holocaust Years. Holocaust Survivors and Remembrance Project: “Forget You Not” (English).

- Homepage: Jewish Education Network. 2000-2006 (Romanian).

- Homepage: Jewisch Community Center București. (English, Romanian).

Individual evidence

- ^ Bernard Lazare: The Jews in Romania. Verlag HS Hermann, Berlin 1902. p. 6.

- ↑ juden-in-europa.de, accessed on September 24, 2010

- ↑ a b Ladislau Gyémánt: The Jews in Transylvania up to the 18th century. In: Volker Leppin, Ulrich A. Wien (ed.): Confession formation and confessional culture in Transylvania in the early modern period. Franz Steiner Verlag, Wiesbaden 2005. p. 191.

- ^ Bernard Lazare: The Jews in Romania. Verlag HS Hermann, Berlin 1902. p. 6.

- ^ Bernard Lazare: The Jews in Romania. Verlag HS Hermann, Berlin 1902. p. 7.

- ^ Johann Daniel Ferdinand Neigebaur: The Jews in Moldavia and Wallachia . In: Latest World Studies. Volume 1. Frankfurt am Main 1848. pp. 252/253.

- ↑ Daniela Oancea: Myths and Past. Romania after the reunification. Inaugural dissertation from the Ludwig Maximilians University, Munich 2005. p. 93.

- ^ Bernard Lazare: The Jews in Romania. Verlag HS Hermann, Berlin 1902. p. 7.

- ^ Johann Daniel Ferdinand Neigebaur: The Jews in Moldavia and Wallachia . In: Latest World Studies. Volume 1. Frankfurt am Main 1848. p. 261.

- ^ Bernard Lazare: The Jews in Romania. Verlag HS Hermann, Berlin 1902. p. 8.

- ^ Johann Daniel Ferdinand Neigebaur: The Jews in Moldavia and Wallachia . In: Latest World Studies. Volume 1. Frankfurt am Main 1848. pp. 261/262.

- ^ Bernard Lazare: The Jews in Romania. Verlag HS Hermann, Berlin 1902. p. 6.

- ^ Bernard Lazare: The Jews in Romania. Verlag HS Hermann, Berlin 1902. p. 16.

- ^ Johann Daniel Ferdinand Neigebaur: The Jews in Moldavia and Wallachia . In: Latest World Studies. Volume 1. Frankfurt am Main 1848. p. 251.

- ^ Bernard Lazare: The Jews in Romania. Verlag HS Hermann, Berlin 1902. p. 23.

- ^ Lothar Maier: Romania on the way to the declaration of independence 1866–1877. Oldenbourg-Verlag, Munich 1989. p. 339.

- ^ Bernard Lazare: The Jews in Romania. Verlag HS Hermann, Berlin 1902. p. 56.

- ↑ Daniela Oancea: Myths and Past. Romania after the reunification. Inaugural dissertation from the Ludwig Maximilians University, Munich 2005. p. 95.

- ↑ Daniela Oancea: Myths and Past. Romania after the reunification. Inaugural dissertation from the Ludwig Maximilians University, Munich 2005. p. 94.

- ^ Bernard Lazare: The Jews in Romania. Verlag HS Hermann, Berlin 1902. P. 73.

- ↑ Daniela Oancea: Myths and Past. Romania after the reunification. Inaugural dissertation from the Ludwig Maximilians University, Munich 2005. p. 94.

- ↑ Edgar Hösch et al., Südost-Institut Munich: Lexikon zur Geschichte Südosteuropas Verlag UTB, Munich 2004. P. 47. ISBN 3-8252-8270-8 .

- ^ Mariana Hausleitner : The Romanization of Bukovina. The enforcement of the nation-state claim of Greater Romania 1918–1944 Oldenbourg-Verlag, Munich 2001. ISBN 3-486-56585-0 . P. 116.

- ↑ Daniela Oancea: Myths and Past. Romania after the reunification. Inaugural dissertation from the Ludwig Maximilians University, Munich 2005. p. 95.

- ↑ Daniela Oancea: Myths and Past. Romania after the reunification. Inaugural dissertation from the Ludwig Maximilians University, Munich 2005. p. 95.

- ↑ Armin Heinen: Romania, the Holocaust and the logic of violence. Oldenbourg-Verlag, Munich 2002. p. 50.

- ↑ Daniela Oancea: Myths and Past. Romania after the reunification. Inaugural dissertation from the Ludwig Maximilians University, Munich 2005. p. 97.

- ↑ Hildrun Glass: Minority between two dictatorships: on the history of the Jews in Romania 1944–1949. Oldenbourg-Verlag, Munich 2002. p. 18.

- ↑ Hildrun Glass: Minority between two dictatorships: on the history of the Jews in Romania 1944–1949. Oldenbourg, Munich 2002. pp. 19/20.

- ^ A b William Totok: Antonescu, Ion. In: Wolfgang Benz (Hrsg.): Handbuch des Antisemitismus , Volume 2: Personen. De Gruyter, Berlin 2009, p. 28

- ^ Memories of the Holocaust: Kishinev (Chisinau). The Operation of the Chisinau Ghetto and of the Camps (1941-1944). Jewish Virtual Library

- ↑ Benjamin Grilj (ed.): Black milk. Letters withheld from Transnistria death camps. Studies Verlag, Innsbruck 2013, ISBN 978-3-7065-5197-7 .

- ↑ Dirk Schümer : Message in a bottle in the sea of destruction. The shattering fate of the Romanian Jews: Letters from the death camps of Transnistria recall a long-forgotten chapter in the history of the genocide . In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, November 30, 2013.

- ↑ Hildrun Glass: Minority between two dictatorships: on the history of the Jews in Romania 1944–1949. Oldenbourg-Verlag, Munich 2002. p. 58.

- ↑ Vladimir Solonari: Ethnic Cleansing or 'Crime Prevention'? Deportation of Romanian Roma. In: Anton Weiss-Wendt (Ed.): The Nazi Genocide of the Roma: Reassessment and Commemoration. Berghahn, New York 2013, ISBN 978-1-78238-923-1 , p. 109.

- ↑ Hildrun Glass: Minority between two dictatorships: on the history of the Jews in Romania 1944–1949. Oldenbourg, Munich 2002, p. 68.

- ↑ a b Saul Friedländer, Martin Pfeiffer: The Third Reich and the Jews: The Years of Destruction, 1939–1945. Beck, Munich 2006, p. 478.

- ↑ Daniela Oancea: Myths and Past. Romania after the reunification. Inaugural dissertation from the Ludwig Maximilians University, Munich 2005. p. 98.

- ^ Report of the Wiesel Commission. (PDF) accessed on September 23, 2010

- ^ Dennis Deletant: Living conditions in the ghettos and labor camps in Transnistria 1924-1944. The Golta case . In: Wolfgang Benz , Brigitte Mihok (ed.): Holocaust on the periphery. Jewish policy and the murder of Jews in Romania and Transnistria 1940-1944. Documents-texts-materials . tape 73 . Berlin 2009, p. 45-70 .

- ↑ Daniela Oancea: Myths and Past. Romania after the reunification. Inaugural dissertation from the Ludwig Maximilians University, Munich 2005, p. 98.

- ↑ Heinz Fassmann, Rainer Münz: Migration in Europe. Campus, Frankfurt am Main / New York 1996, p. 290.

- ^ Dieter Pohl: Persecution and mass murder in the Nazi era 1933-1945. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 2003, p. 79

- ^ Friedrich Battenberg: The European Age of the Jews , Vol. II, Darmstadt 1990, ISBN 3-534-11382-9 , p. 307.

- ↑ Hildrun Glass: The Disappearance of a Minority. The emigration of Jews from Romania after 1944. In: Südosteuropa. Festschrift for Edgar Hösch. Oldenbourg Verlag, Munich 2005. p. 391.

- ↑ Hildrun Glass: Minority between two dictatorships: on the history of the Jews in Romania 1944–1949. Oldenbourg-Verlag, Munich 2002. pp. 81-93.

- ↑ Daniela Oancea: Myths and Past. Romania after the reunification. Inaugural dissertation from the Ludwig Maximilians University, Munich 2005. p. 99.

- ↑ Hildrun Glass: Minority between two dictatorships: on the history of the Jews in Romania 1944–1949. Oldenbourg-Verlag, Munich 2002. pp. 81-93.

- ↑ Hildrun Glass: The Disappearance of a Minority. The emigration of Jews from Romania after 1944. In: Südosteuropa. Festschrift for Edgar Hösch. Oldenbourg Verlag, Munich 2005. p. 391.

- ↑ revista.memoria.ro , Teodor Wexler: Procesul sioniștilor , 7. – 9. July 2000.

- ↑ Teodor Wexler: Dr. Wilhelm Filderman - un avocat pentru cauza naţională a României . Istoric magazine, 1996, p. 81-83 (Romanian).

- ↑ Hildrun Glass: Minority between two dictatorships: on the history of the Jews in Romania 1944–1949. Oldenbourg-Verlag, Munich 2002, p. 185 ff.

- ↑ Hildrun Glass: Minority between two dictatorships: on the history of the Jews in Romania 1944–1949. Oldenbourg-Verlag, Munich 2002. p. 109.

- ↑ Hildrun Glass: The Disappearance of a Minority. The emigration of Jews from Romania after 1944. In: Südosteuropa. Festschrift for Edgar Hösch . Oldenbourg Verlag, Munich 2005. pp. 393/394.

- ↑ Hildrun Glass: The Disappearance of a Minority. The emigration of Jews from Romania after 1944. In: Südosteuropa. Festschrift for Edgar Hösch. Oldenbourg Verlag, Munich 2005. p. 399.

- ↑ Hildrun Glass: Minority between two dictatorships: on the history of the Jews in Romania 1944–1949, issue 112 of the Southeast European Works . Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, 2002, ISBN 3-486-56665-2 , p. 114/115 .

- ↑ Ion Mihai Pacepa : Red Horizons: The True Story of Nicolae and Elena Ceausescus' Crimes, Lifestyle, and Corruption . Regnery Publishing, Inc., 1990, ISBN 0-89526-746-2 , pp. 456 (English).

- ↑ Hildrun Glass: The Disappearance of a Minority. The emigration of Jews from Romania after 1944. In: Südosteuropa. Festschrift for Edgar Hösch. Oldenbourg Verlag, Munich 2005. pp. 383-408.

- ↑ focus-migration.de , Romania.

- ↑ Hildrun Glass: The Disappearance of a Minority. The emigration of Jews from Romania after 1944. In: Südosteuropa. Festschrift for Edgar Hösch. Oldenbourg Verlag, Munich 2005. p. 384.

- ↑ Daniela Oancea: Myths and Past. Romania after the reunification. Inaugural dissertation from the Ludwig Maximilians University, Munich 2005. p. 99

- ↑ Thomas Kunze: Nicolae Ceausescu: A biography. Christoph-Links-Verlag, Berlin 2009. p. 174.

- ↑ Hildrun Glass: The Disappearance of a Minority. The emigration of Jews from Romania after 1944. In: Südosteuropa. Festschrift for Edgar Hösch. Oldenbourg Verlag, Munich 2005. p. 383.

- ↑ juden-in-europa.de , Claus Stephani: Our path is not over yet , In: David , Heft No. 52, March 2002.

- ↑ Daniela Oancea: Myths and Past. Romania after the reunification. Inaugural dissertation from the Ludwig Maximilians University, Munich 2005. p. 100.

- ↑ Daniela Oancea: Myths and Past. Romania after the reunification. Inaugural dissertation from the Ludwig Maximilians University, Munich 2005. S. 113/114.

- ↑ Romania holds first Holocaust Day . BBC News, October 12, 2004.

- ^ Wolf Oschlies : Romanian and German anti-Semitism against the Jews in Romania. ( Memento from November 13, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) In: Shoa.de. Without year (archive.org).

- ↑ sevenbürger.de October 23, 2009; Retrieved September 23, 2010

- ↑ Daniela Oancea: Myths and Past. Romania after the reunification. Inaugural dissertation from the Ludwig Maximilians University, Munich 2005. S. 107/108.

- ↑ Website of the Romanian Central Election Office, accessed on September 23, 2010 ( Memento of October 4, 2017 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 2.1 MB)

Remarks

- ↑ In the social structure of the Securitate employees of all cadres in Romanians in February 1949 the proportion of Jews was 10 percent, and of 60 officers 25 percent were Jews, compared with their proportion of the total population of 2 to 2.5 percent. Source: Gabriel Catalan; Mircea Stănescu: Scurtă istorie a Securității ( German Short History of the Securitate ) . In: Sfera, Politicii . No. 109 , 2004, pp. 42 (Romanian).