Anti-communist resistance in Romania

Anti-Communist Resistance in Romania describes the resistance by political, military and civil groups as well as individuals against the communist regime of the Romanian Communist Party during the People's Republic and Socialist Republic of Romania between the end of the Kingdom of Romania in 1947 and the Romanian Revolution in 1989 .

history

prehistory

Romania under the military dictatorship of Ion Antonescu took part in the war against the Soviet Union on the side of Hitler's Germany from 1941 to 1944 . In the wake of the looming defeat, the country changed sides on August 23, 1944 ( royal coup d'état ) and fought together with the Soviet Union against Germany until the end of the Second World War . Nevertheless, Soviet troops occupied the country. The political leadership of the Soviet Union single-mindedly incorporated Romania into its sphere of influence; the numerically very weak Romanian Communist Party (Romanian: Partidul Comunist Român ) gradually conquered all important positions of power. On December 30, 1947, King Michael I had to abdicate. The supporters of the king, the fascist legionnaires' movement (Iron Guard), but also those of the bourgeois, anti - communist parties were exposed to massive persecution.

The Communist Party also identified numerous students among the opponents of the emerging regime, whose political views were particularly suspicious of them. The party leadership under Ana Pauker decided - possibly on instructions from the Soviet Union - to take extreme action against the actual or suspected anti-communist resistance. On the night of May 14-15, 1948 , about 1,000 students were arrested in Bucharest , Cluj-Napoca and Iași , which was about 2 percent of the number of students at the time. Most of those arrested have been sentenced to at least five years in prison.

Armed resistance in the post-war period

Until their dissolution in 1947, the non-communist parties in Romania resolutely opposed the communists' seizure of power; the churches also defended their traditional rights during this phase.

The resistance forces were similar to those in other Eastern European countries during the transition to communism. Besides the People's Republic of Poland , the Ukrainian SSR and the Baltic States , there were armed resistance groups only in Romania. These had holed up mainly in inaccessible areas of the Carpathian Mountains , but also in the Banat and the Danube Delta . In the first phase, the carriers of these groups were mainly former members of the Romanian military who, after the royal coup in Romania, did not want to fight alongside the Soviet army against the German Empire .

After the defeat of the Third Reich , the resistance groups in Romania took up the armed anti-communist struggle together, but apparently there was no nationwide coordination between the individual groups. In some cases they attacked communist representatives, after which the government branded them “bandits” and “terrorists”. These "partisans" were provided with food by the shepherds in the mountains and by the peasant population, although this often resulted in severe punishment.

The groups - on average between 10 and 40 people - did not pose any major threat to the communist rulers, although they undermined the regime's claim to complete control of the country. They consisted of young people, old people, women (among them some with small children or pregnant women), farmers, former army officers, lawyers, doctors, students, workers. All age, social and political classes were represented. They were armed with pistols, revolvers and machine guns from World War II, but suffered from an acute shortage of ammunition. The underground fighters often had to escape the chase of the Securitate , who organized real hunts in order to capture them - dead or alive. The terrorization of their families through interrogation, the exclusion of their children from school and the use of cruel methods led many of the fighters hidden in the mountains to surrender to protect their families. Some were sentenced to long prison terms and had their property confiscated for "conspiracy against social order", but most were killed. The successful "hunters" received rewards and ranks.

Some of these groups still had a loose connection with German military agencies in Austria and the self-proclaimed Romanian government in exile of the leader of the fascist Iron Guard , Horia Sima . Occasionally the fascist “legionaries” who worked in western countries after 1944 tried to get in touch with the armed groups. In 1949 and 1950 there were broader resistance campaigns in some localities when the communist rulers forcefully forced the farmers to join cooperatives. Some farmers who were wanted by the security police afterwards joined the armed groups in the mountains. After the beginning of the Cold War , Western intelligence services supported the resistance initiatives. Most of the forces smuggled in from abroad were captured by the security forces before they could contact the resistance groups. The groups had trusted that the Western powers would wait for signs of anti-communist resistance to intervene in their support. When there was no intervention after the bloody suppression of the Hungarian people's uprising in 1956, the resistance in the mountains of Romania also subsided.

| Area | Name of the group | Leaders and main characters |

|---|---|---|

| Apuseni Mountains | Garda Albă or Armata Albă, National Defense Front, Hajduk Corps, Organization Cross and Sword | Alexandru Suciu, Nicolae Dabija, Macavei brothers, Iosif Capotă, Alexandru Dejeu, Teodor Șuşman Ioan Robu, Ștefan Popa, Ioan Crişan, Leon Abăcioaiei, Maxim Sandu, Spaniol brothers; Ionescu Diamandi |

| Bistrița-Năsăud County | Iancu Haiducii lui Avramr | |

| Bacau | Uturea | Vasile Cordunean, Gheorghe Ungurașu, Petre Baciu |

| Banat | Partisans of Romania | Ion Uță, Spiru Blănaru, Aurel Vernichescu, Petru Domăşneanu, Nicolae Popovici, Gheorghe Ionescu, Petru Ambruș, Blaj Brothers, Ion Tănase, Dumitru Isfănuț, Nicolae Doran, Ion Vuc |

| Bârlad | Constantin Dan | |

| Brașov | Organization of Vlad Țepeș | |

| Cluj-Napoca | Gheorghe Paşca, Alexandru Podea, Oniga Emil, Deac Cornel | |

| Covasna | Organization of Vlad Țepeș | Victor Lupșa, Corneliu Gheorghe-Szavras |

| Craiova | Ion Carlaon, Marin Dumitraşcu | |

| Dobruja | Haiduken of the Dobruja | Gheorghe Fudulea, the Croitoru brothers, Puiu Gogu, Nicolae Ciolacu, Niculae Trocan |

| Northern Făgăraş Mountains | Ion Gavrilă Ogoranu , Ion Dumitru, Ion Cândea | |

| Southern Făgăraș Mountains | Haiducii Muscelului | Gheorghe Arsenescu, Petru brothers, Toma Arnăuțoiu |

| Gorj district | Mihai Brâncuși | |

| Hunedoara | Lazar Caragea, Petru Vitan | |

| Kreischgebiet and Arad | National Liberation Movement | Valer Șirianu, Adrian Mihuţiu, Gligor Cantemir, Ion Lulușa |

| Maramureș County | Group of priests of the Uniate Church | Gavrilă Mihali-Ștrifundă, Vasile Popșa, Ilie Zubașcu, Ion Ilban, Nicolae Pop, Vasile Dunca |

| Rodna Mountains | Organization cross and sword | Leonida Bodiu |

| Sibiu | Fetea | |

| Suceava County | Tinerii Partizani ai României | Constantin Cenuță, Vasile Motrescu, Vasile Cârlan, Grigore Sandu, Vasile Cămăruță, Silvestru Harsmei, Gavril Vatamaniuc, Ion Vatamaniuc, Vladimir Macoveiciuc, Petru Maruseac, Negre Sumanele |

| Suceava | Gǎrzile lui Decebal | Silvestru Hazmei, Ion Chiraş, Gheorghe Chiraş |

| District of Vâlcea | Gheorghe Pele, Şerban Secu, Ion Jijie | |

| Vrancea County | Vrancea Group, Organization Vlad Țepeș | Paragina brothers, Gheorghe Militaru, Victor Lupșa |

Peasant uprisings in the 1950s

During the period of collectivization of agriculture in Romania between 1945 and 1962, revolts and uprisings of the peasantry repeatedly broke out in large parts of Romania, which were violently suppressed by armed troops.

They were triggered, among other things, by physical attacks that were used by party representatives as a means of persuasion, as well as by harassment with high compulsory taxes for landowners who had not previously entered collectives with their agricultural land.

In July and August 1949 there were dozens of spontaneous local revolts in Băița ( Bihor ), Arad and Botoșani , and in July 1950 in Vlașca ( Ialomița ) and Vrancea. Army , militia and Securitate troops put down the riots, resulting in the wounded, dead, arrests and deportations. According to official information at the time, over 80,000 farmers were arrested from 1949 to 1952, of which around 30,000 were convicted. Their number is likely to be much higher, the death toll was never announced.

After a period of temporary stagnation, collectivization efforts accelerated towards the end of the 1950s. Here again there were peasant uprisings, for example in Suraia and Vadu Roşca (both in Vrancea ), in which at least nine people were killed, and in Cudalbi ( Galați ), Răstoaca (Vrancea), Drăgăneşti-Vlaşca and Olt . One of the punitive actions against unruly peasants was directed in 1960 by Nicolae Ceaușescu . All in all, there was hardly a region in Romania during the period of collectivization that did not revolt.

Attack in Switzerland in 1955

In February 1955, four Romanians in exile from Germany occupied the Romanian legation in Bern , which resulted in a hostage-taking for the release of political prisoners and one dead. The leader of the group, Oliviu Beldeanu, was abducted from West to East Berlin after his release from Swiss custody, arrested there, transferred from the GDR to Romania and sentenced to death there.

Protests from 1956

On November 5, 1956, the student body in Bucharest, Timişoara , Cluj-Napoca and Târgu Mureş prepared for public protests against the Soviet intervention in Hungary. The massive appearance of the security forces only led to the student revolt in Timișoara , where around 300 people were arrested and fifty were sentenced to prison terms. In Cluj-Napoca and Târgu Mureș, all the organizers were not immediately arrested, as there was fear of broad solidarity among the Hungarian minority , but repression gradually took place over the course of the following two years.

There were protests even in Romanian prisons. The largest of these occurred in Aiud Prison , one of the most notorious re-education and labor camps, where around 3,000 prisoners went on hunger strike in 1956.

As in Hungary, some representatives of the Romanian military sought to withdraw from the Warsaw Pact , but the interweaving of punitive measures with economic relief and the lack of a real force that could have brought anti-Soviet feelings and attitudes to a common denominator prevented the Romanian echoes too loud about the Hungarian Revolution and the Polish October . The weak beginnings of criticism of the personality cult around Secretary General Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej , which had made itself felt in intellectual circles shortly before 1956, dissolved after the suppression of the Budapest uprising. Gheorghiu-Dej, who had been employed in 1945, was able to hold onto the head of Romania until his death in 1965. Although the Soviet troops left Romania in 1958, the Stalinist economic concept continued. The forced industrialization at the expense of the peasantry should now serve the "Romanian independence". Because of the brutal methods of forced collectivization , there was widespread resistance in some villages in the winter of 1959/60, but this was ended with the use of violence. At the end of 1956, wages were increased and the supply of consumer goods improved to calm the population.

Kronstadt writers' trial 1959

In 1959, the five Transylvanian-Saxon writers Wolf von Aichelburg , Hans Bergel , Andreas Birkner , Georg Scherg and Harald Siegmund were indicted and convicted in the Kronstadt writers ' trial (Romanian: Procesul scriitorilor germani, the trial of the German writers' group ) . They were accused of having formed an anti-system association and circulating anti-regime literature. It is the only trial of Romania's Stalinist era that has been brought against a group of writers. Von Aichelburg received 25 years (released 1964), Bergel 15 years (released 1964), Birkner 25 years (released 1964), Siegmund 10 years (released 1962) and Scherg 20 years of forced labor (released 1962).

1960s

In the 1960s hardly anything leaked out about political resistance in Romania. In 1964, an amnesty was declared in Romania, during which all political prisoners, more than 50,000, were released. Nicolae Ceaușescu became General Secretary of the Communist Party in 1965 and was well received in the early years of his rule due to his nationalist criticism of the Soviet Union. At this time, Ceaușescu distanced himself from the personality cult and accused the previous party leader and the newly deposed Interior Minister Alexandru Drăghici of “certain attacks”.

Some people have been rehabilitated. From 1964 there was also a cultural “ period of political thaw ”. When Ceaușescu refused to take part in the intervention against the Prague Spring in 1968, many intellectuals who had been rather skeptical of the system up until then joined the party. Among them was the writer Paul Goma , whose story illustrates the futile hope of de-Stalinization .

Paul Goma

Goma was arrested as a student in November 1956 and was only allowed to resume his studies in 1965 after two years in prison and five years of forced residency. In August 1968 his first book The Room Next Door ( Romanian Camera de alături ) came out in Romania. The novel Ostinato , which was written in 1967 and dealt with prison life and the protest actions in Romania in 1956, failed due to state censorship . However, the novel was published in German in 1971 and was presented as "the book of the Romanian Solzhenitsyn " at the Frankfurt Book Fair . As a result, the representatives of Romania demonstratively left the fair. Goma was then no longer able to publish in Romania and in 1973 also lost his job at a magazine editorial office. He made several complaints to the relevant authorities and turned to foreign writers for help.

Goma had hoped to initiate a broad protest movement against the Ceaușescu regime. He spoke of "a Romania that is occupied by Romanians".

However, it was not until 1977 that Paul Goma's three “open letters” achieved a certain level of resonance at home and abroad, with which he followed up the demands of other Eastern European human rights groups. The members of Charter 77 from the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic (ČSSR) , who demanded respect for the Final Act of the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe (CSCE) in Helsinki in 1975, had just come under pressure. In January 1977 Goma expressed his solidarity in an open letter to Pavel Kohout , in which he wrote to the Czech writer that “the Czechoslovakia was occupied by the Russians and Romania only by Romanians”. But poverty and terror are the same. In a second letter, Goma addressed Ceaușescu directly and asked him to support the Czechs and Slovaks in their struggle against the overwhelming Russian forces, as in 1968. At the same time he criticized the attacks by the Securitate secret service . Goma's letters became known in Romania through the Romanian broadcasts of Radio Free Europe . Some listeners expressed their solidarity and support through phone calls or messages sent, including for the first time technical staff and workers.

Soon Goma's phone was blocked and only callers commissioned by the Securitate could still get on the line. At the beginning of February Goma and eight co-signatories wrote a letter to the CSCE conference in Belgrade, in which they demanded respect for human rights. Romania had accepted a code of guaranteed rights by signing the Helsinki Final Act, but had not implemented it in practice. Ceaușescu held a fiery speech in Bucharest against “traitors” and “bought ones”, but without naming Gomas. But since this first major protest action in Romania was followed with interest abroad, Corneliu Burtică , who is responsible in the Central Committee for Ideology and Cultural Issues , declared himself ready to talk to Goma on February 22, 1977. He made no specific concessions and denied that Goma should be isolated. When over a hundred people had already publicly announced their support with Goma's letter to the Belgrade conference, Burtică tried again to persuade Goma to give in. At the same time, the Securitate had placed a professional boxer in front of Goma's apartment block, which prevented unwanted visitors to Goma. Nevertheless, the number of supporters grew to around 200 by the end of March 1977. The Securitate began its offensive at the beginning of April. One of the supporters, the psychiatry professor Ion Vianu, was insulted as a "bandit" and "legionnaire" before the staff meeting of his institute and was subsequently dismissed. Many supporters were beaten on the street or after they were arrested. Like Goma, the Securitate threatened supporters of the Open Letter with assassination attempts on their relatives if they did not withdraw their signature. Some of those arrested were offered to leave for the West , which many accepted.

Goma was detained for over a month and was released on the occasion of a general amnesty for prisoners on the anniversary of Romania's independence in May. He left Romania in November 1977. Since Goma made public statements on the situation in Romania in the years that followed, he received death threats from the Securitate in Paris. In 1983, a person hired for an assassination attempt on Goma revealed himself to the French secret service . The evidence, a pen prepared with a highly effective poison, prompted President François Mitterrand to refrain from his planned state visit to Romania.

Forced political psychiatization

Pitesti experiment

Places of forced political psychiatization in Romania |

From 1949 to 1951, under the rule of Gheorghiu-Dej, political prisoners were forced by the Securitate to torture , kill or re-educate one another as communist-oriented people . This became known as the " Piteşti Experiment ".

The purpose of torture and humiliation was to destroy the prisoners' personalities. The relevant measures were mainly carried out by fellow prisoners or had to be carried out by them. Initially only students were affected, and later other prisoners as well. The ultimate goal was to create a "new man" who would either be a staunch supporter of the communist idea or at least a willless tool of the Communist Party. The measures, now known as the Piteşti experiment, were carried out in several prisons in Romania, including Gherla , Târgu Ocna and Ocnele Mari . However, since the first and most serious incidents took place in the Piteşti detention center , the program was named this city.

Vasile Paraschiv

In the 1970s, the number of people admitted to psychiatric hospitals because of their regime-critical behavior increased . Through the fall of the worker Vasile Paraschiv , this practice, which at that time also spread in the Soviet Union, became known in western countries. Paraschiv had already joined the Communist Party in Ploiesti in 1946 and had no doubts about the system until 1963. At that time he was expelled from the apartment with his wife and two small children because a lieutenant in the police claimed them for himself. The court seised decided in favor of the policeman, which led to the bitterness of the worker and made him want to leave the party in October 1968.

In an open letter to Ceaușescu, he wrote that the party's decisions would not be properly implemented. When he tried to read this letter at the factory, he was prevented from doing so by the management. In July 1969, the police sent him to a mental hospital for the first time. During this targeted action, between 80 and 100 people were brought in at the same time with the aim of silencing critical spirits. Paraschiv went on a hunger strike and was released five days later.

When he tried to determine the legal basis for his admission to psychiatry, he was turned away everywhere. His suggestions on how the work of the unions could be democratized were ignored by the editorial offices and the party leadership. In 1976 Paraschiv was again isolated in a psychiatric institution because he had made contact with a member of a banned social democratic association. In addition, a letter from him to Radio Free Europe had been intercepted. He had to spend 23 days with the seriously ill in a psychiatric hospital; Paranoia was attested to him in the discharge certificate . The Securitate threatened to receive even harsher treatment in the event of further contact with enemies of the state. When Goma's first open letter was read by Radio Free Europe in February 1977 , Paraschiv tried to visit Goma in Bucharest. He was beaten and temporarily arrested. On a further attempt he was arrested in Goma's apartment in April 1977. He was then held in a mental hospital again for 45 days. The prosecutor of Ploiesti has now applied for his "final internment". When eighteen workers from his factory wrote positive replies about his case, they too were threatened. Apparently in the hope that Paraschiv would not return, he was allowed to travel abroad at the end of 1977. After he had himself examined by eight French psychiatrists, and they found no signs of illness, he was able to credibly point to the abuse of psychiatry for political purposes in Romania.

In April 1978 he joined Russian, Czech and Polish dissidents in support of the newly established Russian Free Trade Union . The first time he tried to return to Romania, he was turned away. Due to public pressure he returned to the country in June 1978 and only reappeared as a member of the Sindicatul Liber al Oamenilor Muncii din România (SLOMR, German Free Trade Union of the Working People of Romania ), which was founded in Romania in 1979 . After their suppression, contact with him was no longer possible because his home was constantly screened by the police.

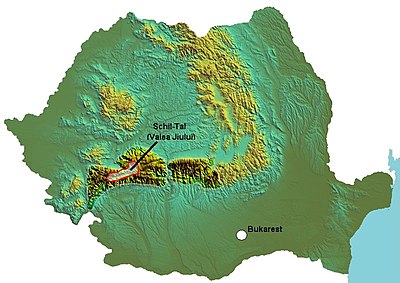

Miners strike in the Schiltal in 1977

In June and July 1977 riots broke out in several large factories in Bucharest, Galați , Piteşti, Craiova and Braşov. At the beginning of August 1977, the largest workers' protests occurred in Romania before December 1989. In the Shilt Valley , where around 60% of Romania's coal reserves are stored, around 35,000 miners are said to have participated in the strike. The reason for this was the changes in social legislation announced in July that restricted sick pay and other social benefits. The special conditions taking into account the special burdens on miners should be abolished, for example the length of a work shift should be increased from six to eight hours and the minimum retirement age from 50 to 55 years. In Lupeni workers gathered on August 1, spontaneous protest, which soon support from the mines around as Uricani , Vulcan , Bărbăteni , PAROSENI , Aninoasa , Livezeni , Dalj , Petrila and Lonea got. The miners held the premises for three days and demanded negotiations with Ceaușescu. The crowd did not leave the fire brigade spraying water after the operation. The Politburo -members Ilie Verdeţ and Gheorghe Pană met on August 2, a spot, but the miners gave their promises no faith. As a result, Ceaușescu broke off his vacation on the Black Sea and traveled to Lupeni on August 3. With his gruff speech, Ceaușescu first insulted the miners, but then promised with his "word of honor" that he would respond to their demands. He said: "Be good people and go back to work, otherwise we will be trodden under". 22 miners explained in a letter addressed to the director of Radio Free Europe that this meant a possible intervention by the Soviet Union. They referred to Ceaușescu's subsequent working visit to Leonid Brezhnev , party leader of the CPSU .

At first the impression arose as if Ceaușescu was keeping his word. The daily working time of the miners was set at six hours and the supply of food was improved. At the same time, however, military units were relocated to the mine sites and the Schiltal was declared a “closed area”, into which travel was only possible with a special permit. The Securitate infiltrated the mine administration and began investigations against the "masterminds" of the protest. In September 1977, the strikers' spokesmen, engineer Jurca and brigade chief Ioan Dobre, were killed in alleged car accidents. The miners sent delegates to Bucharest to protest at Ceauşescu for failure to keep promises. However, they did not get an audience and then lost their jobs. Strikes took place again in October, but this time the security forces were well prepared and were able to suppress the unrest quickly. According to information from miners, around 4,000 colleagues and their families were forced to return to their home communities. For the 22 miners who had turned to Radio Free Europe for support , Amnesty International was able to determine that as a result they could mostly only earn their living at the newly assigned jobs as unskilled workers.

Foundation of "Free Trade Unions" 1979

In 1978 and 1979 there was a major wave of solidarity in Romania. Radio Free Europe reported at this time increasingly on the human rights movement in the Czechoslovak Republic and the “Free Trade Unions” in Poland and Russia. Based on an organization of the Czechoslovak dissidents, the "Association for the Defense of the Unjustly Persecuted" was founded in November 1978 in Brașov. At the end of February 1979 the "Free Trade Union of Romanian Workers" ( Sindicatul Liber al Oamenilor Muncii din România , SLOMR) was founded by five Bucharest intellectuals and fifteen workers from Drobeta Turnu Severin .

The union called for better working conditions and the abolition of unpaid compulsory overtime and the privileges of party officials. After the start-up appeal was broadcast on Radio Free Europe , supporters immediately got in touch. Among them were the aforementioned worker Vasile Paraschiv, as well as other supporters of the Paul Gomas protest in 1977, such as the English teacher Nicolae Dascălu. In March, the cutter Virgil Chender announced a collection of 1,487 signatures from Mureș County and proposed, as an extension of the demands, the free choice of job, no restrictions on farmers in selling their products, and the abolition of terror and forced psychiatry. By the end of April, the SLOMR union had more than 2,000 members across the country and its ranks continued to grow by July 1979.

While the Securitate held back in March because of the state visit by French President Valéry Giscard d'Estaing , it took massive action against the movement in April. All known supporters were arrested and convicted of "parasitism" or other allegations. Two SLOMR spokesmen, who are also known abroad, the doctor Ionel Cană and the economist Gheorghe Brașoveanu were admitted to psychiatric hospitals. The Orthodox theologian Gheorghe Calciu-Dumitreasa had already been imprisoned between 1948 and 1964 and had lost his position as professor at the theological seminary in Bucharest in 1978; now he received the highest sentence among the supporters with ten years in prison. In addition, the Securitate accused him of opposing the state's atheist propaganda in his sermons. When Western human rights organizations called on Romania's church dignitaries to commit themselves to the theologian, Archbishop Nicolae claimed that Calciu-Dumitreasa had not been accused of the content of his sermons, but rather that he had drawn himself “through his political activities from our ranks both as pastor and excluded as citizens ”. Due to foreign pressure, the father did not have to serve his sentence in full; he was released in 1984 and was able to travel to the West.

After a meeting with the SLOMR founding members in February 1979 in Bucharest, Carl Gibson and 16 other sympathizers in Timișoara founded a regional free trade union . The group included the brothers Erwin and Edgar Ludwig from Nerău and Fenelon Sacerdoțeanu , who took over the presidency. On April 4, 1979, after the Radio Free Europe had read out the name of Carl Gibson as the head of the regional group of the free trade union SLOMR, he and Erwin Ludwig were imprisoned for six months in the Popa Şapcă asylum in Timişoara without trial and without a defense attorney “Founding an organization with an anti-socialist character”. After his departure to the Federal Republic of Germany , Gibson continued to campaign for democratic structures in Romania and appeared as spokesman for the SLOMR in the West. As part of an investigation by the International Labor Organization (ILO) initiated by the international trade union confederation Confederation Mondial du Travail World Confederation of Labor , Carl Gibson, among others, was heard as a key witness. The investigation, in which the Romanian government was accused of having failed to respect the agreements on general civil rights and trade union freedoms it had ratified, dragged on from 1981 to 1984 and resulted in the release of long-term convicted union founders.

In October 1979 Ceaușescu accused the “imperialist world of initiating actions against the unity of the working class”. Nevertheless, the unrest was taken into account to the extent that the planned economy provided for higher investments in the consumer and agricultural sectors for 1981 than in previous years.

National minority protests

German minority

|

Members of the Banat Action Group |

From the German minority of the Banat Swabians , a small student group emerged in 1972, called the Action Group Banat . She dealt mainly with literature and was initially unmolested. It was only when Ceaușescu proclaimed the existence of a unified socialist nation at the 11th party congress in 1974 and the policy of "ethnic homogenization" began that it came under increasing pressure. In the autumn of 1975 Gerhard Ortinau , William Totok and Richard Wagner as well as the Bucharest literary critic Gerhardt Csejka were arrested on the pretext of attempting to flee the border. As a cautionary note, William Totok should be charged with “anti-socialist attitudes” and “disseminating fascist writings”. Because friends in the West stood up for Totok, he was released after eight months of pre-trial detention. Then he had to prove himself in "production" for a few months before he could continue studying. Since the Banat Action Group was not in line with the adjusted representatives of the German minority in the Banat, broader support was not to be expected. The protest of the small group against the harassment of its members died away as well as that against the cancellation of German radio programs in Timișoara. The German newspapers in Romania reported on the protests of the Timişoara writers only after the fall of Ceauşescu.

Hungarian minority

While the German minority was only 1.6 percent of the total population in 1977, according to Romanian data it was 7.9 percent for the Hungarians. Hungarian dissidents found support from this minority, which represented a far more significant part of society as a whole.

Károly Király from Târgu Mureş - until 1972 a member of the Politburo and in 1975 the Central Committee (ZK) of the Romanian Communist Party (Romanian: Partidul Comunist Român ) - wrote several open letters in the autumn of 1977 in which he protested against the worsening situation of the Hungarian minority . Until the publication of his letters abroad in early 1978, he held the position of Vice-President of the Workers' Council of Hungarian Nationality .

The first, still very cautiously worded, letter was addressed to the Hungarian Politburo member Fazekas and the subsequent more critical letter to János Vincze , who represented the Hungarian nationality in the Central Committee. Király complained that his proposals to improve the situation of the minorities were being ignored by the relevant party organs and demanded that his letters be discussed in the Politburo. The Nationalities Councils established in 1967 had degenerated into a propaganda instrument for deceiving foreign countries. Since they are only of an advisory nature, their suggestions would mostly end up in the files. The situation of the minorities had deteriorated further and further in the last few years, for example the education system in the minority languages had been severely curtailed since 1976. In places with a predominantly Hungarian population, Romanians without knowledge of the Hungarian language are often used as mayors or party secretaries, and many plant managers do not understand the language of the majority of the workforce. Since 1975 all Hungarian place-name signs have disappeared.

The party leadership responded to these letters in October 1977 with a summons to the disciplinary department of the Central Committee, in which Király was asked about his "collaborators". He said he wrote the letters alone, but many would share his views. He was then released with instructions to name such people. Király found support from former Prime Minister Ion Gheorghe Maurer , who retired in 1974 , the director of the Editura Kriterion publishing house , Géza Domokos , as well as several university professors, theater directors, journalists and doctors. Nevertheless, he was relieved of his duties and placed under police supervision. When the letters appeared in western countries in the spring of 1978, Király was arrested and then isolated with his family for some time. In May 1978, at the plenary session of the Workers' Council of German and Hungarian Nationality , Ceaușescu noted that “reactionary forces” wanted to incite the minorities to a civil war against the Romanians. Despite his isolation, Király managed to speak up later. In the 1980s, he was the first to sign an appeal to the United Nations , formulated by the writers Géza Szőcs and Dorin Tudoran , from which they demanded the formation of a commission on minority problems that should also deal with the situation in Romania.

Géza Szőcs, Attila Ara-Kovács and Károly Tóth published the first Hungarian-language samizdat publication in Romania with the name Ellenpontok ( German nodes ) in nine editions between 1981 and 1982 . In November 1982, some of the Hungarians involved in the publication of the magazine were arrested in Miercurea Ciuc . Ara-Kovács and Tóth were able to travel to Hungary at the end of their imprisonment. Szőcs remained in Romania until 1986, but his circle of friends was still under surveillance and harassed after he left. Because of this breach of the state's information monopoly, a decree was issued in 1983 that subjected typewriter owners to strict control by the militia.

Resistance to Ceaușescu's program of systematisation was also strongest on the Hungarian side. The towns that the authorities had classified as "not capable of development" were to be converted into arable land. While many Romanian farmers were being relocated to the apartment blocks in the next larger town, the Hungarians were already protesting vehemently against the planning, as the destruction of Hungarian villages would mostly have meant forced assimilation into Romanian-dominated towns. This struggle received broad support from Hungary . In June 1988, 25,000 people took part in a rally organized by the dissidents in front of the Romanian embassy in Budapest. This was the largest non-state-controlled protest in the country since 1956.

Protests in the 1980s

Despite continued repression, there were further workers' protests in the 1980s. In February 1981, unrest spread in a rolling mill and chemical factory in Bucharest and in the petrochemical plants of Ploieşti and Piteşti. In October 1981 the miners went on strike in the Motru city area . Little is known about these protests and their suppression to this day.

While the protests from the ranks of the minorities were mostly carried out by a group of intellectuals, some Romanian intellectuals criticized the system on an individual basis until 1989. The literary scholar Doina Cornea from Cluj-Napoca described how even good friends and relatives withdrew after their first "problems with the Securitate". In 1983 she lost her position at the Babeș-Bolyai University of Cluj due to a critical letter to Radio Free Europe . In 1987 she was in custody for five weeks because she had distributed 160 leaflets just after the workers' unrest in Brasov. It was not until 1988 that the worker Iulius Filip, the doctor Dumitru Alexandru Pop, the poet Teohar Mihadaș , the painter Isaiah Vâtcă and the teachers Gina and Dan Sâmpleanu Cornea's criticism of systematization signed . Some of the signatories were beaten during interrogation. Cornea was under house arrest until December 1989. The Securitate tried to prevent the British Ambassador Arbuthnott from visiting Cornea's apartment.

In May 1983, the young engineer Radu Filipescu distributed self-printed leaflets in Bucharest mailboxes. In it, he called on the recipients to express their protest against Ceaușescu by taking a two-hour walk in a certain place on Sundays. Filipescu was arrested by the Securitate and sentenced to ten years in prison. Shortly thereafter, his father, a well-known doctor, tried "secretly" to contact prominent figures in order to persuade them to take an action critical of the regime, but this failed.

In Aiud Prison, Radu Filipescu met other people who had also made leaflets. Due to pressure from abroad, Filipescu was released early after three years in prison. When he distributed leaflets again in December 1987 and gave an interview to a French television team, the Securitate reacted irritably. This time he was beaten during interrogation. After the then French Prime Minister Jacques Chirac campaigned for Filipescu and Doina Cornea, who had been arrested for the same television program, both were released.

In 1983 a new protest group called "Movement for Freedom and Social Justice" was created. Its initiator Dumitru Iuga was sentenced to twelve years in prison, his helpers to five years. In 1985 the "Romanian Democratic Action" called for political and economic reforms.

In the 1980s there were always new protests, although the initiators were often silenced by the most brutal means. The Securitate used torture methods on persons unknown abroad, although Romania had committed itself by signing international treaties not to use force against prisoners. There have also been deaths during interrogation, such as the case of the engineer Gheorghe Ursu , who was arrested in January 1985 for denunciation. The Securitate confiscated his personal diary in which he had expressed himself critical of Romania's domestic and foreign policy. Urzu died in December 1985 from internal injuries in the sick section of Jilava Prison . In October 1986 the engineer Ion Puiu signed a joint declaration by dissidents from Hungary, Poland and the Czechoslovak Republic on the anniversary of the 1956 revolution. During the interrogations that followed, he was beaten. After Ceauşescu's fall, the worker Paraschiv reported that the Securitate had isolated him from the outside world since 1979 and had beaten him to hospital several times.

Short worker protests flared up again and again, for example in 1982 in a truck plant in Brașov, 1985 in Timișoara, 1986 in Cluj-Napoca, Arad and Turda . The largest riots since the miners' strike of 1977 occurred in November 1987 during the Brașov uprising ; again a spontaneous action. The party officials had planned that the workers of the truck combine Intreprinderea Autocamionul Brașov " Steagul Roșu " ( German Red Flag ) should participate in the local elections directly from the shift. Even when moving to the polling station, the angry workers were chanting slogans directed against Ceaușescu. Once there, around 4,000 people stormed the party building. Pictures of Ceaușescu and propaganda material were burned and the "valuables from the party canteen" were plundered. In the afternoon, the security forces managed to stifle the riot before news of the uprising could penetrate other cities. Only weeks later, when the repression had taken hold, were brief reports on so-called "hooligans" and "vandalism". In December 1987, dockworkers in should Constanta went on strike, although the details remain unknown to date.

In the run-up to the revolutions in 1989 , the Securitate tried to be present everywhere. However, it could not prevent the aforementioned Radu Filipescu, together with six other political prisoners released from Aiud prison, from founding the “Libertatea” ( German freedom ) union in May 1988 and their catalog of demands from reaching abroad. At the end of 1988 three Bucharest journalists and a printer began preparing to publish an illegal newspaper. The Securitate was able to arrest Petre Mihai Băcanu's group while printing the first page. After four months, all but Băcanu were released; he was now accused of "illegal business".

In March 1989 resistance from the ranks of the Communist Party also reported. A group of six old communists had sent a protest letter to Ceaușescu, in which they demanded that he respect the agreements of the Helsinki Final Act and renounce the systematisation program and food exports. The letter caused a sensation abroad as the signatories had once held high positions. They were interrogated and pressured to distance themselves from their letter. They were then under house arrest. The writer Mircea Dinescu was also cut off from the outside world after the French newspaper Liberation published a critical interview with him in March 1989.

Although the mass protests in Eastern Europe in late autumn 1989 had put the communist leaderships, with the exception of Albania, on the defensive, Romania remained quiet until mid-December 1989. On December 14th, leaflets appeared in Iași calling for protest assemblies, but the assembly area had been largely shielded by the Securitate. In view of the impending blood bath, the authors of the appeal did not take action. The spark of the Romanian Revolution in 1989 should emanate from some members of the Hungarian Reformed Congregation in Timișoara , who wanted to prevent the forced transfer of their pastor László Tőkés . Since December 13th, despite the constant siege of the Securitate, they have not left his house.

On December 16, the protest spread to the townspeople, and the demonstrators, pushed back by the Securitate, began to defend themselves. It was only the tough crackdown on the part of the Securitate and the army, who used armored vehicles, and especially the shots at some children who protested with candles, that caused the anger of broad groups to flare up. The lists of deaths show that in Bucharest on December 21 and 22 it was mainly young people who defied the armored vehicles. There was no organization of dissidents in Romania that could have influenced the further development after the escape, overthrow and execution of Nicolae Ceaușescu and his wife Elena . Most of the people whose resistance actions were described first got to know each other personally in the newly created Council of the Front for National Rescue . After giving this organization credibility through their names, however, they were soon pushed into the background by the new rulers.

Monica Lovinescu , who from 1964 onwards had contributed to building internal resistance in Romania against the Ceaușescu regime with two broadcasts a week on Radio Free Europe, accompanied the revolution from France as a radio presenter.

Commemoration

The Sighet Memorial is a memorial to the victims of communism and anti-communist resistance in Romania. The memorial is located in Sighetu Marmației , in the far north of Romania, directly on the border with today's Ukraine (in the communist era on the border with the Soviet Union), in the building of a former penal institution.

The building, which was built in 1897 by the Austro-Hungarian authorities as a public prison in what was then Máramaros County , was converted into a political prison by the communist regime in 1948 and was feared until 1989 because of the particularly strict prison conditions.

The prison acquired its special significance as a prison for the country's elite in May 1950, when 150 political prisoners were admitted (50 more were added later). They included leading church members, top politicians from the illegal democratic parties, former ministers, intellectuals and generals, and later also critical communists.

The Catholic bishops Anton Durcovici and Valeriu Traian Frențiu died of starvation there in 1951 and 1952 respectively. Particularly prominent prisoners were the politicians Iuliu Maniu from the National Peasant Party and Dinu Brătianu from the National Liberal Party , who were seen as a beacon of democracy in Romania ; Iuliu Maniu and the pro-fascist historian Gheorghe Brătianu died in prison in 1953.

Although there was hardly any torture in the prison, around 25 percent of the inmates died during their detention, as the detention conditions without a heating system, with meager meals and harassment by the guards affected the prisoners, who were mostly over sixty years old. In 1955 an amnesty was issued, but the more important inmates were only transferred to other prisons.

The director of the memorial is the former dissident Ana Blandiana .

rating

William Totok , a former member of the Banat Action Group , wrote in 1997:

- "Fear, oppression and mistrust are inherent characteristics of every dictatorship, but the lack of any solidarity - as in Romania during the Ceaușescu period - is even beyond the imagination of a reader who knows a totalitarian regime from personal experience."

The historian Mariana Hausleitner wrote in 1996:

- “Little is known about dissidents from Romania during the years of the Ceaușescu era. For one thing, the protest was mostly isolated and short-lived. Unlike in Poland, Hungary or the CSSR, there were no groups in Romania that created a counter-public with their criticism. Second, Romania played a special role in the perception of the West because of Ceaușescu's foreign policy, which differed in some points from that of the Soviet Union. Therefore hardly anything was conveyed about the tentative resistance attempts in Romania from the western media up to perestroika . The third reason why even today historians do not concern themselves with the protests in the Ceaușescu era is related to Romania's development after 1989. The new archive law keeps the holdings of the Ceaușescu era completely under lock and key, which severely restricts research. With the methods of oral history, one could at least reconstruct the world of ideas of those who resisted in the 1970s and 1980s on this topic . This has not yet begun, however, suggesting that there is a problem with the Romanian intellectuals behind this. Most of them lived in the Ceaușescu era in a privileged way, measured against the total population, and therefore took little risk. Why should they expose themselves to counter-questions from people who have been driven to rebellion by social pressure or idealism and severely punished for it? The only resistance actions that are widely discussed by the public and by scholars in Romania today are those of the years before 1956. The anti-communist resistance groups in the mountains are particularly popular. There you can weave in new national myths and at the same time include at least some army members in the new ancestral chain. "

literature

- Karl-Heinz Brenndörfer: Bandits, Spies or Heroes? Armed anti-communist resistance in Romania 1948–1962. Stuttgart 2005, ISBN 3-00-015903-7 .

- Carl Gibson : Symphony of Freedom. Resistance to the Ceausescu dictatorship. Chronicle and testimony of a tragic human rights movement in literary sketches, essays, confessions and reflections. JH Röll Verlag, Dettelbach 2008, ISBN 978-3-89754-297-6 .

- William Totok, Elena-Irina Macovei: Între with şi bagatelizare. Despre reconsiderarea critică a trecutului, Ion Gavrilă Ogoranu şi rezistenţa armată anticomunistă din România (Between myth and belittlement. On the critical coming to terms with the past, Ion Gavrilă Ogoranu and the armed, anti-communist resistance in Romania 2016)., Edita Polşiirom

Web links

- Mariana Hausleitner : Political Resistance in Romania , 1996 (→ online 53–57.pdf Part 1 (PDF; 55 kB), Part 2 )

- Hans Bergel : The Unknown Revolt - Armed resistance against the communist dictatorship in Romania , 2004 (→ online )

- William Totok : Coming to terms with the past between myth and trivialization - On the armed anti-communist resistance in Romania , 2004 (→ online )

Remarks

- ↑ Hanns-Stephan Haas subdivided “ethnic homogenization” into two basic types: violent assimilation and physical expulsion, if not even murder, of the ethnically allogeneic population, i.e. the population with a different origin and / or culture. (→ Ethnic homogenization under duress. Types and progression models. )

- ↑ According to Hungarian sources, the data from the 1977 census were manipulated in order to restrict the rights of the minority. According to M. Hausleitner, representatives of the minority calculated a figure of 2.5 million instead of the official 1.7 million Hungarians in Romania. In August 1982, Der Spiegel named around two million Hungarians in Romania.

- ↑ In order to better understand the political implications of the father's act, it must be added that the Radus family on their mother's side is related to Petru Groza , the first communist prime minister of Romania . Herma Kennel , author of the book There are things you just have to do. The resistance of the young Radu Filipescu , Herder Verlag, Freiburg-Basel-Wien, 1995, wrote on p. 170: “All acquaintances that Dr. Filipescu spoke out against the regime. But nobody was ready to support a specific action. "

Individual evidence

- ^ A b Gheorghe Boldur-Lățescu: The communist genocide in Romania. Nova Science Publishers, New York 2005, ISBN 1-59454-251-1 , p. 21, in English

- ↑ Alexandru Daniel Popescu: Petre Țuțea: between sacrifice and suicide. Ashgate Publishing Ltd, Aldershot 2004, ISBN 0-7546-5006-5 , p. 69, in English

- ↑ Dennis Deletant : Communist terror in Romania: Gheorghiu-Dej and the Police State, 1948-1965. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, London 1999, ISBN 1-85065-386-0 , pp. 200f, in English

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l Mariana Hausleitner : Political Resistance in Romania , 1996, (→ 53–57.pdf online part 1 ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was created automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this note. (PDF; 55 kB) • Part 2 ( Memento of the original dated February 2, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this note. )

- ↑ a b Memorial Sighet : Museum: Room 48 - Anti-Communist Resistance in the Mountains (→ online )

- ↑ Ionitoiu Cicerone: Rezistenţa Anticomunista din Munţii României, 1946-1958. Gîndirea Românească, 1993 (→ online ), in Romanian.

- ↑ Adrian BRISCA: The Anticommunist Armed Resistance in Romania, 1944-1962. AT, no. 34-35, 1-2 / 2002, pp. 75-101, in English.

- ↑ Cristian Troncotă: Procesul mişcării naţionale de rezistenţă. P. 225, in Romanian.

- ^ Grupul de rezistenţă maior Nicolae Dabija. In: Memoria. No. 13, pp. 59-67, in Romanian.

- ↑ Lucretia Jurj-Costescu: Patru ani de rezistentă cu arma în mână în Muntii Apuseni in Memoria. Revista gândirii arestate, No. 26, in Romanian (→ online ( Memento of November 11, 2014 in the Internet Archive ))

- ↑ Radu Ciuceanu, Octavian Roske, Cristian Troncotă: Începuturile mişcării de rezistenţă. vol. 2, 1946, Bucharest, Institutul naţional pentru studiul totalitarismului, 2001, doc. 1-10, pp. 30-40, in Romanian.

- ↑ Cristian Troncotă: Procesul mişcării naţionale de rezistenţă. 1946, in: Arhivele Totalitarismului, no. 19-20, 2-3 / 1998, pp. 102-120, in Romanian.

- ↑ Atanasie Berzescu: Lacrimi şi sânge. Rezistenţa anticomunistă armată din munţii Banatului. Editura Marineasa, Timişoara, 1999, in Romanian.

- ↑ Adrian BRISCA: Rezistenţa Armata din Banat. vol. 1, 1945–1949, Editura Institutul Naţional pentru Studiul Totalitarismului, 2004, in Romanian.

- ↑ Tudor Matei: Rezistenţa Anticomunista din Mehedinti. In: AS, 1998, 6, pp. 250-255, in Romanian.

- ↑ Emil Sebeşan, Ileana Silveanu: Rezistenţa din Banat 1949. In: A tot, 1998, 6, nr. 1, pp. 116-138, in Romanian.

- ^ Theodor Bărbulescu, Liviu Țăranu: Rezistenistena anticomunistă - Cazul colonelului I. Uță in Memoria. Revista gândirii arestate no. 44-45, in Romanian (→ online ( Memento from November 11, 2014 in the Internet Archive )).

- ↑ Petre Baicu, Alexandru Salcă: Rezistenţa în munţi şi oraşul Brașov (1944-1948). Ed. Transilvania Express, Brașov, 1997, in Romanian.

- ↑ Radu Ciuceanu, Octavian Roske, Cristian Troncotă: Începuturile mişcării de rezistenţă. doc. 10, p. 153, in Romanian.

- ^ Paula Ivan: Aspects du mouvement de resistance anti-communiste a Cluj et a Alba, 1947-1952. In: Trans. R, 1995, 4, no. 4, pp. 116-121, in Romanian.

- ↑ Marian Cojoc: Rezistenţa Armata din Dobrogea, 1945-1960. Ed. Institutul Naţional pentru Studierea Totalitarismului, Bucharest, 2004, in Romanian.

- ↑ Zoe Radulescu: Rezistenţa Anticomunista din Munţii Babadag. In: AS, 1995, 2, pp. 311-319, in Romanian.

- ↑ a b Ion Gavrliă Ogoranu, Lucia Baki: Brazii se frâng, dar nu se îndoiesc , Vol.III, Editura Marineasa, Timişoara, in Romanian.

- ↑ Claudia Căpăţână, Răzvan Ciolcă: Fişe pentru o istorie a rezistenţei anticomuniste. Group "Haiducii Muscelului". In: MI, 1998, 32, no. 6, pp. 40-44, in Romanian.

- ↑ Steliana Breazu: Grupul de rezistenţă anticomunistă al lui Cantemir Gligor din munţii Zarandului şi munţii Codrului, pe valea Crişului Alb. AS, 1995, 2, pp. 334-337, in Romanian.

- ↑ Ștefan Bellu: Rezistenţa în munţii Maramureşului. AS, 1995, 2, pp. 320-326, in Romanian.

- ↑ Adrian BRISCA: Rezistenţa Armata din Bucovina. vol. al II-lea, 1950–1952, Institutul National pentru Studiul Totalitarismului, Bucharest, 2000, in Romanian.

- ↑ Adrian BRISCA: Jurnalul unui partizan Vasile Motrescu şi Armata rezistenţa din Bucovina. 2005, in Romanian.

- ↑ Adrian BRISCA, Radu Ciuceanu: Rezistenţa Armata din Bucovina. Vol. I, 1944–1950, Bucharest 1998, in Romanian.

- ↑ a b c d e f g Adrian Stǎnescu: Din istoria rezistenţei anticomuniste in România. Curierul Românesc, Year XVI, no. 5 (208), May 2004, pp. 8-9, in Romanian.

- ↑ Radu Ciuceanu, Octavian Roske, Cristian Troncotă: Începuturile mişcării de rezistenţă. doc. 2, pp. 138-147, in Romanian.

- ↑ Mihai Timaru: Lupta de rezistenţă anticomunistă în munţii Vrancei. In: AS, 1995, 2, pp. 327-333, in Romanian.

- ↑ a b c d Katharina Kilzer, Helmut Müller-Enbergs : Spirit behind bars: The Romanian Memorial Sighet , Volume 16 of Forum: Romania, Frank & Timme Verlag, 2013, ISBN 3-86596-546-6 , 213 pages, P. 79 f.

- ↑ Kenneth Jowitt: Revolutionary Breakthroughs and National Development: the Case of Romania, 1944-1965. University of California Press, 1971, ISBN 0-520-01762-5 , 317 pp., P. 99, in English.

- ↑ a b c Keno Verseck : Romania , Volume 868 by Beck series, CH Beck Verlag, 2007, ISBN 3-406-55835-6 , 226 pp, p. 74.

- ↑ a b c Thomas Kunze : Nicolae Ceausescu: A biography. Ch. Links Verlag, 2009, ISBN 978-3-86153-562-1 , p. 464, here p. 125 (→ online )

- ^ Winfried Heinemann, Norbert Theodor Wiggershaus: The international crisis year 1956: Poland, Hungary, Suez. Volume 48 of articles on military and war history, Oldenbourg Verlag, 1999, ISBN 3-486-56369-6 , p. 722, here p. 437, (→ online )

- ↑ Renate Windisch-Middendorf: The man without a fatherland. Hans Bergel - life and work. Forum: Romania, Vol. 5, Berlin, 2010, p. 45.

- ↑ Sven Pauling: We will imprison them because they exist. Study, contemporary witness reports and Securitate files on the Kronstadt writers' trial in 1959. Berlin, 2012, ISBN 978-3-86596-419-9 .

- ↑ a b c William Totok : Resistance against the Ceausescu regime - Rezistenta împotriva regimului ceausist , 1997 (→ online )

- ↑ Vladimir Tismăneanu: Stalinism for all seasons: a political history of Romanian communism . In: Societies and culture in East-Central Europe, Vol. 11. University of California Press, 2003, ISBN 0-520-23747-1 , p. 36, in English.

- ↑ Dennis Deletant : Ceaușescu and the Securitate: coercion and dissent in Romania, 1965–1989. Verlag ME Sharpe, New York 1995, ISBN 1-56324-633-3 , p. 29, in English.

- ↑ Keno Verseck : Vasile Paraschiv: "I just want you to say: I wasn't crazy." , January 1, 1999 (→ online )

- ^ Carl Gibson : The brief flash of resistance - founding and smashing the first free trade union in Romania - an experience report (→ online ; PDF; 1.8 MB).

- ^ Carl Gibson Institute : Documents on the history of the "Free Trade Union of Romanian Workers" "SLOMR" in the Banat - from the CNSAS Securitate files , August 16, 2012 (→ online )

- ^ Siebenbürgische Zeitung, Carl Gibson: Legitimate Protest against the Ceaușescu dictatorship , March 20, 2009 (→ online )

- ↑ Radio Transylvania: Interview with Carl Gibson, Anti-Communist Resistance (→ online )

- ↑ a b kulturraum-banat.de (PDF; 86 kB), Siebenbürger Zeitung, Elisabeth Packi: Resistance against the Ceauşescu dictatorship , August 10, 2009.

- ↑ World Confederation of Labor : Report (→ Interim Report - Report No 218, November 1982 )

- ↑ George Bara: Biografia secreta a lui karoly kiraly unul dintre instigatorii conflictului din martie 1990 de la Tg-Mures , March 24, 2010, in Romanian (→ online ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was created automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. )

- ↑ Der Spiegel : Separated Parts - The Hungarian minority in Romania defends itself against Ceausescu's rigid nationality policy - for the first time with support from Budapest. 34/1982 (→ online )

- ↑ Vladimir Tismăneanu : Commentary. Why Does Monica Lovinescu Matter? In: Radio Free Europe of April 24, 2008.

- ↑ Biography on the homepage of the Diocese of Iași, in Romanian (→ online )

- ↑ Silvestru Augustin Prunduş, Clemente Plăianu: Catholicism and Orthodoxy Romanian. Brief history of the Romanian United Church , Christian Life Publishing House, Cluj 1994.

- ↑ Jiulius Maniu in the Munzinger archive ( beginning of article freely available)

- ↑ Gazeta de Bistriţa: Eroii rezistentei anticomuniste, Sighetmormantul elitei romanesti , in Romanian (→ online ( Memento from November 5, 2013 in the Internet Archive ))

- ↑ Memorial Sighet : The memorial for the victims of communism and resistance (→ online )