History of Slovenia

Slovenia has been an independent state in Central Europe since 1991 and has been a member of the European Union since May 2004. The area of present-day Slovenia has been inhabited mainly by the ancestors of present-day Slovenes since the end of the 6th century. At the end of the 8th century the area came to the Frankish Empire and remained part of the Holy Roman Empire . Divided into various margravates and duchies, the area cameunder the rule of the Habsburgs in the late Middle Ages and in 1918 became part of the newly founded Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes , which was later called Yugoslavia. During the Second World War , Slovenia was divided and placed under German and Italian occupation. In 1945 Slovenia came to the re-established, but now communist Yugoslavia. On June 25, 1991, Slovenia broke away from the State Union of Yugoslavia and declared its independence.

Time to the Middle Ages

Prehistory and early history

Around 250,000 BC The first stone tools were made by humans, which were found, for example, in the Loza caves (not far from Postojna ). Around 2000 BC Chr. Built people of the Bronze Age pile dwellings in a bog near the present-day Ljubljana . Settlements on hilltops, surrounded by ramparts, which were probably built by the Illyrians , dissolved around 1200 BC. The pile dwellings. These in turn were used by the Celts in the 3rd century BC. Chr. Destroyed. Around the same time, Aegida ( Koper ) was founded by Greek merchants as a base on the northern Adriatic .

Taurisker

The Tauriskians were from the 3rd to the 1st century BC. A Celtic tribal association on the eastern edge of the Alps , whose settlement area is mostly limited to Carinthia and Slovenia. Your relationship with the Norikers is not entirely clear. After the battle of Telamon in 225 BC The Tauriskians were part of the Celtic allies who suffered a heavy defeat against the Romans . Those parts of the Tauriskians who were not involved in the battle settled on the Upper Save and subsequently traded gold with the Romans. Gold production increased their political and economic power. Together with the Boiern, Norikum was repeatedly threatened and Noreia attacked. At that time the Tauriskians were likely to have been subordinate to the Boians . 60 BC BC the allies were subject to the Dacians under Burebista . Then they had to allow other Celtic tribes, called Latobics , to settle on their territory in what was later to be Carniola .

Roman Empire since 9th BC Chr.

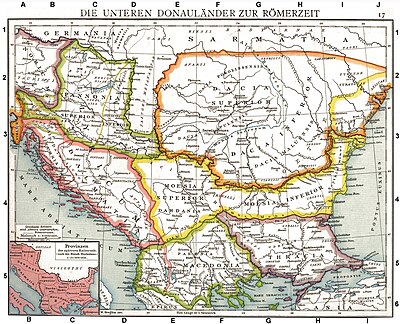

About fifty years later, the Roman Empire had provisionally reached the height of its power under Gaius Julius Caesar , who gave the Julian Alps its name. But it was only under his stepson and successor Octavian, who later became Emperor Augustus , that the Kingdom of Noricum and the Taurisk region were conquered. Under his stepson and successor Tiberius, the area was in the year 9 BC. Pacified and divided into the Roman provinces of Noricum, Pannonia and Dalmatia . The center and capital of Noricum was Virunum on the Zollfeld in Carinthia. The now Roman province was ruled from here.

The first cities developed from military camps: Emona (Ljubljana), Piranum ( Piran ), Claudia Celeia ( Celje ) and Poetovio ( Ptuj ). The new masters promoted the copper and iron industry of the long-time residents, built an extensive road network and used the many thermal springs. Gradually the country developed into an important region of the empire, the population was Romanised.

The region had an important geographical and strategic function for the Romans, as it represented an important land connection between Central and Southeastern Europe and Italy. When the incursions of Germanic tribes into Italy increased in the 3rd century, the Claustra Alpium Iuliarum , a barrier system of walls and fortifications, was built in the Julian Alps at the beginning of the 4th century under the rule of Emperor Diocletian . A center of this system was the fortress Ad Pirum on the pass of the Birnbaumer forest in the northwest of today's Slovenia.

From the 2nd century onwards, the Danube was the northern border (Danube Limes ) of the Roman Empire. All the legions to secure the Roman provinces were located there, while the inland cities remained unfortified. This meant that barbarians who had broken through at the borders were able to penetrate deep into the interior of the empire with almost no obstacles. In the third century, which was politically uncertain for Rome, the Sarmatian tribes of the Jazygens and Roxolans, living in the greater area of the Hungarian lowlands , took advantage of the situation to reach the southwestern edge of the Pannonia superior province during their raids in 259/260 . They wreaked havoc on the northeastern area of present-day Slovenia.

Only at the beginning of the 4th century, under the reign of Emperor Diocletian, were both the administrative units and the legions divided. In many cities in the new sub-provinces of Noricum Mediterraneum and Pannonia prima ( from which late ancient Slovenia was formed ), Roman troops were stationed for security. The two sub-provinces then belonged to the Pannonian-West Illyrian diocese with the capital Sirmium . The western part of today's Slovenia was with the province Venezia-Histria part of the Dioecesis Italiae with the capital Milan . The two inner Norse cities of Celeia and Poetovio are located in the former Spodnja Štajerska / Lower Styria. To 381 - on the synod of Aquileia - made himself the Bishop of Poetovio, Julian, Valens, gothic by wearing costumes suspicious Arians to be or even "heathen priest," as we conduct a review of orthodoxy by the Bishop of Milan Ambrose know . There, in the presence of Ambrosius, Bishop Anemius of Sirmium called himself "Church Father Illyrien". Due to the political upheavals of the following events, neither Milan nor Sirmium were able to maintain their ecclesiastical patronage in today's Slovenian area. The jurisdiction of Aquileia was limited to the westernmost areas of Slovenia.

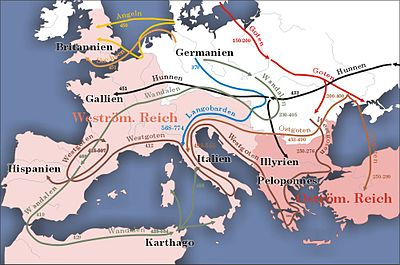

Great Migration

In the autumn of 376 many Goths , who were besieged by the Huns in the Russian area , were accepted into the Roman Empire. In January 395, the Western Roman Emperor Theodosius I died , who had reunited the Roman Empire in the Battle of Frigidus near Wippach / Vipava (autumn 394), but after his death the empire finally split into the Roman and Byzantine Empire . All the federal government of the empire and the peoples of the Pannonian plain became restless with his passing and no longer felt bound by their treaties. In 379 - one year after the Battle of Adrianople - the Goths came to the Julian Alps (Slov.: "Julijske Alpe"), that is, to the late antique Carnia / Carniola , an area on the Upper Sava, which later extended to Italy and Norikum was enough. The church father Hieronymus described a period of around twenty years in 396, during which the Goths, Sarmatians , Quads , Alans , Huns, Vandals and Marcomanni devastated today's Slovenian area.

Around 397, Marcomannic federations were settled in the Pannonia prima ( called "Valeria" since Emperor Valens ), which also included the easternmost part of Slovenia - the Prekmurje on the other side of the Mur . The Marcomannic Queen Fritigil exchanged letters with Bishop Ambrose of Milan in order to bring about the conversion of her people to Catholicism . Just like the quads, the marcomanni soon gave up their special name and have since been considered Suebi , which can be traced in the Pannonian-Slovenian region until the end of the Longobard rule in 568.

In the autumn of 401, Alaric I and his Goths occupied the area between Pannonia and Italy in order to attack the Apennine peninsula from there. However, they were destroyed by Stilicho a year later (402). In 405 another Ostrogothic army passed through what is now Slovenia and devastated Pannonia, Norikum and Italy.

“In the years 408 and 409, the Alaric Goths tried to gain a foothold in the Noric-West Pannonian region. First they marched to Emona / Laibach / Ljubljana, which was in the Venetian-Istrian province and therefore in Italy. After that they moved into the Styrian-Slovenian inland noricum. First, Alaric was here closest to the road over the Birnbaumer Wald / Hrušica, that is, the route to Italy that he had already tried in 401. Second, his brother-in-law Athaulf was in Pannonia and commanded the Gothic-Hunnic cavalry warriors here. Thirdly, at the end of August, beginning of September 408, Alaric offered the evacuation of Norikum and the withdrawal of the troops to Pannonia, which also suggests that the king had concentrated most of his army in the eastern interior Norikum. However, when all offers were rejected, the Alaric Goths left their Norican quarters at the beginning of October 408, but did not retreat to Pannonia, but invaded Italy. "

While the Goths were moving to Rome, the pagan Generidus was appointed magister militum from Ravenna for the provinces of Noricum and Pannonia in 409 . The province of Dalmatia was also under his command . At that time, the Archdiocese of Milan gradually lost its sphere of influence over what is now Slovenia to the Patriarchate of Aquileia .

In the first third of the 5th century Pannonia became the center of the Huns , from 445 Attila achieved sole rule. His reign lasted until 453. In Pannonia, Attila brought a period of relative calm. In 448 or 449, representatives of the province of Noricum also arrived at the court of Attila in addition to Eastern Roman envoys - among them the Comes Romulus from Poetovio / Pettau / Ptuj , the grandfather of the last Western Roman emperor Romulus Augustulus . After Attila's death, the Huns were defeated by a Germanic coalition led by Gepids in 454 or 455 at the Battle of Nedao . At that time, the sphere of influence of the Byzantine Empire extended to the province of Noricum, and it was the Eastern Roman Emperor Markianos who, before his death in 457, arranged for the Ostrogoths to settle by treaty in what is now Slovenia.

At the beginning of the reign of the Western Roman Emperor Anthemius (467–472), the army master Ricimer , who was of Gothic- Suebian origin, succeeded one last time in protecting Norikum's Roman statehood from the Goths, their allies and their opponents. Soon after his death, however, the church order and thus also the Roman administration crumbled in the entire Norikum until around 490. The Romanized population emigrated to Italy or withdrew to remote mountain valleys. Place names with the prefix lasko or lahko still bear witness to the existence of Romanesque enclaves in Slovenia. Odoacer's seizure of power in 476 marked the end of the Roman Empire. Ravenna stopped paying wages.

On August 28, 489, Ostrogoth troops under the Gothic king Theodoric the Great crossed the Isonzo and inflicted a heavy defeat on Odoacer. During the three-year conflict between the two rulers (490–493), the Slovenian region was left to its own devices. Only under the rule of Theodoric the Great was he reunited with Italy.

In the disputes between Theodoric the Great and the Byzantine Empire, the area of present-day Slovenia, which he had inherited from Odoacer, was repeatedly the deployment area of competing armies. The two opponents only made peace in 510. The still existing inland Norikum had the task of protecting Italy against Pannonia under Theodoric. Norikum was established as a military district ( ducatus ).

At the beginning of the 5th century, the Lombards appeared in the Pannonian region under the rule of King Wacho , who originally allied themselves with the Byzantine Empire and thus became the opponent of Theodoric. 536 to 537 Wacho also tolerated the Franconian expansion via the formerly Gothic-Italian Norikum. In 545 the Franks even occupied Veneto , and the later Slovene area was under Franconian influence for the first time. But then the alliances between the Lombards and the Byzantine Emperor Justinian I came back into play, who renewed his treaties in 547 to 548 in order to minimize the influence of the Franks south of the Alps.

In the course of this, the Lombards occupied the areas of present-day Slovenia, primarily between the Save and Drava, including the municipality of Ptuj , while the remaining Noro-Slovenian areas remained the Franks. In the spring of 552 an army of Justinian I moved via Istria to Italy and was accompanied by 5500 Lombards. After the destruction of the Ostrogoth Empire, however, the Lombards remained on their own and concentrated their power in what is now the Slovenian area, which they successfully defended on all sides. In the 540s they were able to win the favor of the Noriker, and from 555 there were also family ties to the Franks. Under King Alboin (561-572), at the urging of the Avars, the Lombards left what is now Slovenia and turned to Italy. The conclusion of a contract with the Avars around the year 568 guaranteed them their possible presence in Italy and, in return, the Lombards a 200-year right of return to what is now Slovenian territory.

In the Roman provinces of Noricum and Pannonia, the Roman statehood did not end in one fell swoop. In the area of present-day Slovenia, the ties to Rome remained until the Lombards withdrew in 568. Even the Avars preserved the forms of organization of late antiquity until their demise. It was only the Franks who separated the eastern Noro-western Pannonian region from Italy.

After Rome withdrew from Ufer-Noricum and Binnen-Noricum, the Celtic-Roman population as well as the Germanic tribes resident here only partially migrated. Names of places and names are retained in the Noric region even after the collapse of the Roman administration.

middle Ages

Origin of Carantania

After the Lombards withdrew, the Avars and their Slavic subjects, who had immigrated with them from the east, took possession of this vacated area.

From the second half of the 6th century, the Baiwar Agilolfinger were the new opponents of this Slavic-Avar "community of nations". In 592 there was the first major clash with Tassilo I , to which the Alpine Slavs were subject. In 595, however, the Bavarian Agilolfingers lost almost their entire tribal army , 2,000 warriors, when the Slavs were supported by the cavalry of the Avar Chagans . Both disputes can be located in what is now the Austrian Upper Drautal.

After the weakening of the Avars in 626 due to conflicts with the Byzantine Empire, the Slavic Samo Empire emerged in the power vacuum between the Bavarians and the Avars , to which, according to Czech and Slovak historians, the areas of present-day Carinthia and present-day Republic of Slovenia did not belong , although Samo was able to extend his influence to the Alpine Slavs. For other historians, however, Carinthia and Slovenia were very much part of the Samo Empire. With Samos death 658 the reports end up over his kingdom, but even after death Samos remained the Alpine Slavs under their Wallucus (= ruler ) free from the dominion over the Avars.

Around or after 610 the Alpine Slavs again prevailed against the Bavarians, this time against the Agilolfinger Duke Garibald II in Aguntum in what is now East Tyrol . With these armed conflicts, the Alpine Slavic sphere of influence expanded to the Upper Styrian Enns , in the Salzburg Enns-Pongau , the Pongau side valleys of the Salzach into the Gastein Valley , and to Innichen in the Puster Valley in what is now South Tyrol. This proto-Slovene principality with its center in Karnburg (Slov. Krnski grad) on the Zollfeld north of Klagenfurt was called Karantanien .

The ritual on the Carinthian Fürstenstein , which has become the “national myth of the Slovenes”, is neither to be interpreted as an enthronement ritual nor as a genuinely Slavic or Germanic ceremony. It is an initiation rite: the prince goes into a rural setting, integrates himself into the Edlinger group . The basic phenomenon that fortified farmers are directly subordinate to the king is already known from the Ostrogoth times. The ritual can be very old, go back to the Carantan period, but it can also have arisen in the 10th century. In any case, it is a wrong assessment to see the prince stone as the founding symbol of the Slovenian nation. The Slavic empire of the Carantans certainly did not extend south over the Karawanken into the Carniola . Slovenian historical research also sees it that way.

Franconian Empire, since 788

This independence did not last long, because in 788 the Principality of Carantania was conquered by the Franks. Under Charlemagne , the Slovene leadership was eliminated and the country evangelized by the dioceses of Aquileia and Salzburg . The ecclesiastical division of the karantanic area between the Archbishop of Salzburg and the Patriarch of Aquileia became essential for the further development, as the boundary of which was established in 796 at a bishops' conference on the Danube, on the occasion of Pippin's Avar campaign , the Drau, a regulation that was established in 803 was confirmed by Charlemagne. The parts of Carantania south of the Drava were in future ecclesiastically Aquileia, politically the Margrave of Friuli . In 796 the Avars were finally defeated and the south-east of the empire was divided into two different brands. The Pannonian Mark and the Mark Friuli were separated by the Drava. After the division of the Frankish Empire, Bavaria's influence increased. Many German colonists were also brought into the country, who later formed the middle and upper classes. Trade, church and politics remained in German hands until the end of the Habsburgs .

Changing rulers

In 863 the Slav apostles Cyril and Method of Saloniki translated the Bible into Slavic and developed their own script, the Glagolitic alphabet . At the end of the 9th century the Carolingian Empire broke up and the Carantan nobleman Kocelj formed the independent Balaton Principality , which also included parts of eastern Slovenia and lasted until 876.

The Slavs demanded the right to a church independent of Salzburg. Pope John VIII appointed Method Archbishop of Pannonia ( Neutra ) in 880, with his seat in Sirmium . In the middle of the 10th century the Hungarians who immigrated from the steppes of Asia began their raids. From Slovenia to Italy and southern Germany, many countries were affected. Only the victory of the German king and later emperor Otto I in the battle on the Lechfeld near Augsburg in 955 eliminated this danger. The Hungarians now established themselves in the Pannonian Plain, separating the settlement areas of the southern Slavs from those of the western and eastern Slavs.

976 Karantanien was as a result of the dispute between Henry the Wrangler and King Otto II. The duchy of Bavaria separated and the Duchy of Carinthia charged one, unlike the tribal duchies noninheritable Office Duchy of Holy Roman Empire with the dependent brands Krain and Styria ( "Carinthian Mark "). The not very numerous Slovenian nobility had all but disappeared by the 10th century. The Slovenian peasants lost their freedom almost completely to the landlords, who were almost independent because of the frequently changing rulers. The Eppensteiner (1000-1122), and the Spanheimer (1122-1269) including the Andechs-Meranier (1173-1209) provided the dukes until these families died out and some dukes of different sexes ruled before the long reign of the Habsburgs began.

In 1261, Styria, which had already become its own duchy in 1180, and in 1269 also Carinthia and the Margraviate of Krain, came into the possession of the Bohemian King Ottokar Przemysl II for a short time , but after his death in the battle on the Marchfeld in 1278 these countries became after Krain when Pfand and Carinthia were initially given to the Meinhardiners until 1335 , almost entirely by the Habsburgs. In the 200 years after Carinthia was elevated to the status of a duchy, there was a strong immigration of Bavarian and Franconian farmers into what is now the Austrian federal states of Carinthia and Styria. In the following centuries, German increasingly replaced the Slavic language in these areas, except for the border areas in the south of Carinthia. The Alpine Slavs were assimilated, but even in the areas with the greatest German settlement this process took several centuries. The Slavic population element lasted the longest in Upper Styria and Carinthia. In Lower Styria / Štajerska , which is now part of Slovenia , German language islands were formed , for example around Marburg an der Drau (Maribor), in Pettau , in Cilli and - despite its name - in Windisch-Feistritz . In the Upper and Lower Carniola the Gottschee language island and language islands in Zarz (area of the Selzacher Zayer ), around Wochein (Bohinj), in Bischoflack (Škofja Loka), Assling (Jesenice) and Laibach . In the county of Gorizia , a German language island was created in the Wippach Valley.

On the northeastern Adriatic, the rich maritime republic of Venice gained more and more power from the 12th century , expanding its dominion over Dalmatia and Istria with the exception of Trieste , which became part of the Habsburgs in 1382. All of the country's resources have been exploited. The partly vegetation-free karst areas of Istria and Dalmatia are the product of the overexploitation of the Venetians, who cleared the forests for shipbuilding and the pile foundations of their lagoon city. It was not until Napoleon ended the rule of Venice over the Adriatic coastal towns in 1797 with the creation of the Illyrian provinces .

Counts of Cilli, 14th and 15th centuries

The county of Sanegg in Cilli ( Celje ) was able to assert itself against the Habsburgs in the 14th and 15th centuries. The most famous count was Hermann II. His son was raised to the rank of imperial prince in 1436 and thus freed from the feudal rule of the Habsburgs. His daughter Barbara was married to the German emperor Sigismund (1387 King of Hungary and 1420 King of Bohemia). Thanks to a clever marriage policy , large parts of Slovenia and Croatia were in the hands of this family, whose last male member Ulrich von Cilli was killed in an attack by Ladislaus Hunyadi in 1456 . Due to his childlessness, the entire area fell back to the Habsburgs.

Modern times

Habsburgs

In 1473 there were peasant unrest and revolts that dragged on for almost 100 years. Due to feudal oppression and frequent Turkish invasions , the country was bled and turned to the Reformation . This led to the blossoming of a Slovenian national consciousness. Primož Trubar had the first Slovenian books printed in Tübingen in 1551 (a catechism and a primer). Jurij Dalmatin translated the Bible and Adam Bohorič wrote a Slovenian grammar. But clergy and nobility - with exceptions such as Andreas von Auersperg (Slovenian: "Andrej Turjaški") - countered with the Counter-Reformation . With military force and the Inquisition , the area of today's Slovenia was re-Catholicized.

For the next 300 years the Slovenian territory was a rural and quiet area of the Habsburg Monarchy . During the reign of Maria Theresa (1740–1780) it experienced an economic boom. The administration and taxation were reformed and compulsory schooling with Slovene lessons in the first grades was introduced. Her son Joseph II went even further with his reforms. He abolished serfdom in 1782 and gave everyone the right to exercise their religion freely. In 1797 the first Slovenian newspaper, Ljubljanske Novice, appeared .

Illyrian Province and Congress of Vienna 1815

Parts of today's Slovenia were occupied by Emperor Napoléon in 1809 and Carniola, Istria , the western part of Carinthia and Dalmatia were organized as Illyrian provinces with the capital Ljubljana . Now the Slovenian language and identity “awoke” again. Napoléon completely abolished feudal rule, freed the remaining unfree peasants, built schools and roads and laid the foundation for industrialization . After his defeat and the Congress of Vienna , the old state was restored under the new name of the Kingdom of Illyria and the Habsburg region was extended to Dalmatia and Veneto .

Revolution 1848/1849 and dual monarchy

The economic upswing that began in Europe also affected Slovenia. Viticulture, mining and textile industries were expanded. In 1849 the railway reached Ljubljana, from Trieste via Adelsberg ( Postojna ). And in 1854 - after the successful completion of the route over the Semmering - it was possible to travel from Vienna via Marburg an der Drau and Cilli to Ljubljana. The revolution of 1848/49 moved the Slovenian intellectuals and the first calls for Slovenian self-government were made. The Carinthian clergyman Matija Majar-Ziljski formulated his manifesto for a United Slovenia (“ Zedinjena Slovenija ”), the Gottschee-German Peter Kosler drew his provocative and immediately censored map of the “Slovenian lands” without just including the official German place names the terms customary in Slovene usage. The national poet of Slovenia France Prešeren (Preschern) formulated the longing for self-determination in his poems and literary works. Between 1869 and 1871, the popular assemblies called “Tabori” emerged as the nucleus of the political consciousness of the Slovenes. The union of all South Slav peoples in a federation within the k. u. k. Reich was now openly propagated. The Slovenian writer Ivan Cankar and the Croatian Bishop Josip Juraj Strossmayer were their best-known protagonists. Jurisprudence and administration in Cisleithanien showed a much fairer treatment of the Slavic and Romance nationalities than in Transleithanien , even if the Austrian administrative policy towards the Slovenes in southern Styria and, until shortly before the outbreak of war, also in Carniola ... could be used as counterexamples in many cases .

20th century

First World War, 1914–1918

With the assassination of the Austrian heir to the throne Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo on June 28, 1914, the First World War began . The Slovenes fought loyally on the side of the Austro-Hungarian armies, mainly on the Russian front ( Josip Broz Tito was taken prisoner here) until Italy declared war on Austria-Hungary on May 24, 1915. Now the war on the Isonzo began . From Trieste to South Tyrol , the troops on both sides fought against each other under the most difficult conditions on the Alpine front. Over a million soldiers were killed in the twelve Isonzo battles.

SHS State and Royal Yugoslavia

After the fall of the Habsburg Empire , the National Council of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs was formed in Zagreb on October 6, 1918, claiming the right to represent all southern Slavs of the Danube Monarchy. On October 29, this National Council decided to break away from Austria-Hungary and to merge all southern Slavs into a new country. With the war winners Serbia and its king at the head (until August 1921 Peter I , then Alexander I ), the SHS state was formed . In November 1920, however, Slovenia had to renounce areas it claimed for itself - karst and coast - in the Rapallo border treaty in favor of Italy. From a Slovenian point of view, the planned two referendums in southern Carinthia on joining the new state of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs also failed , so that not all Slovenes could be united in one state. As a result, around 350,000 Slovenes were separated from the around one million Slovenes in the motherland. In what is now the Italian coast , the Slovenian-Croatian underground organization TIGR fought for the connection to Yugoslavia.

Serbian dominance in the new state was soon felt to be oppressive. The Vidovdan Constitution of St. Vitus Day 1921, the Serbian national holiday commemorating the Battle of the Blackbird Field in 1389, as well as the royal dictatorship proclaimed in 1929 increased the discontent of many Slovenes even though the Slovenian People's Party under Anton Korošec participated in many governments of the new state was involved. The royal dictatorship began on January 6, 1929; on October 3, the name of the state was changed to Yugoslavia. Yugoslavia was divided into nine Banats ; the Drava-Banat roughly corresponded to the Slovenian settlement area. Without having solved the integration problems of the new Yugoslavia, King Alexander was murdered on October 8, 1934 by Macedonian and Croatian terrorists in 1934 in Marseille. He was followed by 11-year-old Peter II ; his uncle Paul ran the government.

Although its domestic political situation was deeply disrupted, Yugoslavia retained its political neutrality at the beginning of the Second World War . However, the Axis powers Germany and Italy urged Prince Paul to join on March 25, 1941. Two days later, the Serbian-dominated military leadership launched a coup d'état, who made the seventeen-year-old Crown Prince Peter head of government and immediately terminated membership. The German Reich , which now saw Yugoslavia as a factor of uncertainty on its south-eastern flank, brought World War II to Yugoslavia with its air raid on Belgrade on April 6, 1941. In the Balkans campaign , German and Italian troops crossed the border in Slovenia, the royal Yugoslav army was overrun and forced to surrender on April 17, 1941.

Slovenia in World War II, 1941–1945

See also: CdZ area Lower Styria

The occupation had serious consequences for Slovenia. The land was divided:

- The south and west up to and including Ljubljana was occupied by the Italian army and incorporated into the Kingdom of Italy as the province of Ljubljana . After Mussolini's fall , the area was placed under the German Supreme Commissioner in the Adriatic Coastal Operation Zone in Trieste from October 1943 .

- Hungary received the Prekmurje region in the northeast.

- The German-occupied areas of Carinthia and Carniola and Lower Styria were each under a head of the civil administration (CdZ) and were intended for formal integration into the Greater German Reich .

- A small piece of Slovenia north of the village of Bregana was occupied by the newly independent state of Croatia .

On April 12, 1941, the SS-Obergruppenführer Reinhard Heydrich , the head of Sipo and SD , had a resettlement staff set up with the task of resettling Slovenes and " Windische " insofar as this seemed "racially and politically necessary". The plan was to expropriate around 220,000 to 260,000 Slovenes and then relocate them. In April 1941 the Styrian Heimatbund was also brought into being, which was a compulsory organization of the German minority with the task of Germanizing the CdZ area . The deportations began on May 26, 1941, initially to Croatia and Serbia , and from autumn 1941, because of the resistance movement in these countries, to Lower Silesia , Brandenburg, Hanover, Thuringia, Württemberg, Bavaria, Baden and the Sudetengau . From June 7th to September 27th 1941 14,634 people were transported from Lower Styria to Serbia and Croatia, and from Upper Carniola from July 6th to 10th 1941 2,337 people were transported to Serbia. This particularly affected the educated classes, including the clergy. On October 23, 1941, the targeted depopulation of the so-called " Ranner triangle" (at the confluence of the Krka and the Save ) began. By July 30, 1942, but mostly by December 9, 1941, around 36,000 Slovenes of all classes - mostly farmers and winegrowers - were deported to the " Altreich ", mostly for forced labor in German industry. For various reasons, however, the actual resettlements did not reach the planned figures by a long way; on the contrary, including 17,000 Slovenes who had fled to the Italian province of Ljubljana, a total of 80,000 people. Ethnic Germans from other areas of Yugoslavia and Eastern Europe were to take the place of the deportees . The German-speaking Gottscheers were resettled from their linguistic island in southern Slovenia, which belonged to the Italian occupied territory, to the deported areas of the Ranner triangle in the German-occupied part of the Slovenian Lower Styria. In addition to Gottscheers, ethnic Germans from Eastern Europe, including Bessarabian Germans and Dobrudscha Germans , as well as South Tyrolean Optanten were settled here.

But the resistance soon formed. Just a few days after the occupation of Slovenia by the Axis powers, communists, left Catholics and left-wing bourgeois intellectuals founded the Slovene Anti-Imperialist Front in Ljubljana on April 26, 1941, shortly afterwards renamed the Liberation Front ( Osvobodilna Fronta , OF), which began with the establishment of a partisan army . The Yugoslav communists , since 1937 under the leadership of Josip Broz - alias Tito, who was of Croatian-Slovenian origin, were initially paralyzed because Stalin was still allied with the German Reich. Only after the German attack on the Soviet Union did communist resistance increase. Soon the communist party managed to take full control of the OF. The communist partisans not only fought against the occupiers themselves, but also against their allies, the Domobranci ( "Belogardisti" , a conservative, clerical / Christian and anti-communist home guard of "White Guards") as well as against the loyal Yugoslav army in the fatherland ("Plavogardisti") ) . It is assumed that 32,000 Slovenes were killed in the Second World War, that is 2.5% of the population.

Towards the end of the war and after the war, there were serious war crimes by Tito partisans in what is now Slovenia, for example in the Hornwald and during the expulsion of German-speaking parts of the population (camp Laško / Tüffer, Strnišče / Sterntal and Teharje / Tüchern), but also in neighboring Lower Carinthia, occupied by partisans ( Bleiburg massacre ). A Slovenian commission set up by the conservative Janša government in 2004 estimated that 15,000 Slovenes were executed without a court judgment in the first two months after the end of the German occupation. The number of liquidated Croatian, Serbian, Montenegrin and German soldiers as well as members of the German minority in the anti-tank ditch at Tezno near Maribor is also estimated by the investigators at 15,000. The Barbara studs of Huda Jama could contain the skeletons of 4,000 victims, so far more than 400 have been recovered

In 2010 over 600 mass graves were registered. The Tito partisans killed around 100,000 people after the end of the war. Of these, more than 14,000 were Slovenes, plus 20,000 German soldiers and members of the German-speaking minority, as well as tens of thousands of Croats and also Serbs, Montegrins, Italians and Hungarians. A decision made in 2009 to rename a street in the capital after Tito was declared unconstitutional two years later.

After the Second World War

After the war, most of the former Austrian coastal area fell from Italy to the Yugoslav republics of Slovenia and Croatia. Since the hinterland of Gorizia (Gorica / Görz) came to Slovenia, but most of the city to Italy, the Slovenian city of Nova Gorica was founded. For the strongly mixed, controversial area around Trieste, the Free State of Trieste was established in 1947 as a provisional , which was placed under international control. When it was dissolved under the London Agreement of October 5, 1954, the city of Trieste and its surroundings (Zone A) fell to Italy, the hinterland in the south (Zone B) to Yugoslavia. The final division of the area was regulated in the Osimo Treaty and came into force in 1977.

Independence since 1989/1991

On January 17, 1989, the Central Committee of the Slovenian Communists committed itself to political pluralism, thus opening the way to a multi-party system in Slovenia. On September 27, 1989, the Slovenian Parliament passed a constitutional amendment that allowed Slovenia to secede from Yugoslavia. In addition, the rights to free and secret elections and free political association were established while remaining in the Yugoslav state association. On December 7, 1989, the anti-communist bourgeois parties in Ljubljana united to form the DEMOS ( Democratic Opposition Slovenije , Democratic Opposition of Slovenia) bloc and achieved an absolute majority in parliament in the first multi-party elections after the end of the war. However, the presidential elections on April 22, 1990 were won by the Communists' leading candidate, Milan Kučan .

On June 25, 1991, Slovenia broke away from the State Union of Yugoslavia and declared its political independence , which triggered a military intervention by the Yugoslav People's Army . In the so-called 10-day war , an occupation of the country by the Serbian-dominated army was prevented by the relatively well-organized resistance with the formation of the Slovenian territorial defense. There were several rather small skirmishes between the territorial defense and the Yugoslav Federal Army, especially at border crossings, when Slovenian customs officers took control there, but the Yugoslav army wanted to recapture these crossings. Several air strikes were carried out, in the course of which Austrian territory was injured several times . The conflict left 39 dead on the part of the People's Army, 13 on the Slovenian side and 10 foreign nationals killed.

Ultimately, however, there was no major destruction, which favored the development of the Slovenian economy, which had already been the richest part of the country, after independence. The danger of a civil war, as it was taking place in other parts of Yugoslavia, never existed, since the Slovenian population, apart from smaller minorities, consists almost entirely of Slovenes , while in the following conflicts the question of the Serbian minorities and their change to Serbian State was at the center of the disputes.

With the mediation of the United Nations and the Austrian government , a compromise was finally reached: Slovenia was supposed to suspend its independence for a period of three months and during this time the Yugoslav People's Army had to withdraw completely from Slovenia. Both sides adhered to the agreement, and so on October 8, 1991 the independence of the Republic of Slovenia came into effect. Since Croatia refused to allow the Yugoslav People's Army to cross its territory, the soldiers had to be relocated to Montenegro by ship . However, no heavy weapons could be taken with them, so this equipment was left behind in Slovenia.

Austria declared the recognition of the new state planned for January 15, 1992 on December 19. On December 19, 1991, the German government announced that it would recognize Slovenia's independence on December 23, which it then did. The Vatican recognized Slovenia on January 13, 1992, on January 15 the other eleven EEC countries joined in accordance with the decision of December 16, 1991, and by the end of January 1992 Slovenia was recognized by the majority of the international community as an independent state .

Since then, the country has stabilized quickly and is considered the most advanced formerly socialist reform state. Remaining minor border disputes with neighboring Croatia over sea areas on the Adriatic were largely settled when it joined the EU in 2013 , but the borders have not yet been finally determined. In addition, there are still different views regarding the definition of the sea border in the Adriatic. The Permanent Court of Arbitration awarded Slovenia a large part of the Piran Bay in 2017 . This ruling is not recognized by Croatia, which had previously withdrawn from the arbitration proceedings. The European Court of Justice , which was then called upon by Slovenia, declared itself inconsistent in 2020.

Since joining the EU in 2004

After the decision at the EU summit on December 13, 2002 in Copenhagen, Slovenia was admitted to the European Union on May 1, 2004 along with nine other states . Thanks to its good economic development, Slovenia has been a net contributor since accession . It has been part of the European Monetary Union since January 1, 2007 , the euro replaced the Slovenian tolar .

The rapid economic development of the state has been dampened since the global economic crisis in 2007. It was considered a candidate for the euro rescue package in 2008 , but was able to consolidate its budget independently through privatizations and a strict austerity and reform program. There were also several government crises.

See also

literature

- Peter Štih, Vasko Simoniti, Peter Vodopivec: Slovenian history. Society - Politics - Culture (= publications of the Historical Commission for Styria. 40; = Zbirka Zgodovinskega časopisa. 34). Graz 2008, ISBN 978-3-7011-0101-6 .

- Slavko Ciglenečki: Slovenia. In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde (RGA). 2nd Edition. Volume 29, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2005, ISBN 3-11-018360-9 , pp. 123-128. (on-line)

- Joachim Hösler: Slovenia. From the beginning to the present. Pustet, Regensburg 2006, ISBN 3-7917-2004-X .

- Helmut Rumpler , Arnold Suppan (Hrsg.): History of the Germans in the area of today's Slovenia 1848-1941. (Zgodovina nemcev na obmožju današneje slovenije 1848–1941. ) (= Series of publications by the Austrian Institute for Eastern and Southeastern Europe. 13). Publishing house for history and politics / Oldenbourg, Vienna / Munich 1989, ISBN 3-7028-0279-7 .

- Herwig Wolfram (Ed.): Austrian History 378–907. Boundaries and spaces. History of Austria before its creation. Ueberreuter, Vienna 1995, ISBN 3-8000-3524-3 .

Web links

- 1. Slovenia - moving ahead in the liberation front

2. Trieste or Trst?

3. Partial republic in Tito's Yugoslavia

4. The exit is decided

on the pages of: Der Standard.at/Wwissenschaft - Slovenes and Germans in World War II

Individual evidence

- ↑ Joachim Hösler: Slovenia. From the beginning to the present. Verlag Pustet, Regensburg 2006, ISBN 3-7917-2004-X , p. 264.

- ↑ Peter Petru: The East Alpine Taurisker and Latobiker. In: Hildegard Temporini (ed.): The rise and fall of the Roman world. Political history. Provinces and fringe peoples. Latin Danube-Balkan area . Verlag de Gruyter, Berlin 1977, ISBN 3-11-006735-8 , pp. 482 and 487.

- ↑ Peter Petru: The East Alpine Taurisker and Latobiker. In: Hildegard Temporini (ed.): The rise and fall of the Roman world. Political history. Provinces and fringe peoples. Latin Danube-Balkan area . Verlag de Gruyter, Berlin 1977, ISBN 3-11-006735-8 , p. 490f. and 495.

- ↑ a b Joachim Hösler: Slovenia. From the beginning to the present. Verlag Pustet, Regensburg 2006, ISBN 3-7917-2004-X , p. 15.

- ^ Slavko Ciglenečki: Slovenia. In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde. Volume 29. Walter de Gruyter. Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-11-018360-9 , p. 123.

- ↑ Philipp von Rummel : Habitus barbarus. Clothing and representation of late antique elites in the 4th and 5th centuries. Verlag de Gruyter, Berlin 2007, ISBN 978-3-11-019150-9 , p. 128 ff.

- ↑ Herwig Wolfram (ed.): The birth of Central Europe . Verlag Kremayr and Scheriau, Vienna 1987, ISBN 3-218-00451-9 , p. 35.

- ↑ Herwig Wolfram: The Empire and the Germanic Peoples . Verlag Siedler, Berlin 1998, ISBN 3-442-75518-2 , p. 264 ff.

- ^ Daniela Schetar, Friedrich Köthe: Slovenia. Ljubljana - Julian Alps - Adriatic Coast. DuMont Reiseverlag, 2003, ISBN 3-7701-5991-8 , p. 27.

- ↑ Walter Pohl : The Avars. A steppe people in Central Europe 567–822 AD . Verlag Beck, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-406-48969-9 , p. 57.

- ↑ Walter Pohl: The Avars. A steppe people in Central Europe 567–822 AD . Beck, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-406-48969-9 , p. 150.

- ↑ a b c d Peter Štih: Search for history, or how the Karantan prince stone has become the national symbol of the Slovenes. ( Memento from February 21, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Information portal of the Central Association of Slovenia. Organizations and the Slovenian Cultural Association, October 30, 2006.

-

^ Herwig Wolfram: Salzburg, Bavaria, Austria. The Conversio Bagoariorum et Carantanorum and the sources of their time. (= Communications from the Institute for Austrian Historical Research. Supplementary Volume 31). Oldenbourg, Vienna / Munich 1995, ISBN 3-486-64833-0 , p. 43. and

Helmut Beumann, Werner Schröder (Ed.): Early Middle Ages Ethnogenesis in the Alpine Region. Thorbecke Verlag, Sigmaringen 1985, ISBN 3-7995-6105-6 , p. 130. -

↑ cf. the map of Samos area in Stephen Clissold, Henry Clifford Darby: A short history of Yugoslavia from early times to 1966. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge-London 1968, ISBN 0-521-09531-X , p. 14. Fig. 4 and

Joseph Slabey Rouček: Slavonic encyclopaedia. Philosophical Library, Kennikat Press, Port Washington NY 1949, p. 463. - ^ Maria Crăciun (Ed.): Ethnicity and religion in Central and Eastern Europe. Cluj Univ. Press, Cluj / Klausenburg 1995, ISBN 973-96280-7-9 , S, p. 18.

- ↑ Herwig Wolfram (ed.): The birth of Central Europe . Verlag Kremayr and Scheriau, Vienna 1987, ISBN 3-218-00451-9 , p. 95.

- ^ Heinz Dopsch , Hans Spatzenegger : History of Salzburg. Volume 1: Prehistory, Antiquity, Middle Ages. Universitätsverlag A. Pustet, Salzburg 1981, ISBN 3-7025-0121-5 , p. 166.

- ↑ Bernd Moeller, Gerhard Ruhbach (Hrsg.): Remaining in the change of church history. Church history studies. Verlag Mohr, Tübingen 1973, ISBN 3-16-135332-3 , p. 103.

- ^ A b Hermann Wiesflecker: Austria in the age of Maximilian I. The unification of the countries to form an early modern state. The rise to world power. Verlag Oldenbourg, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-486-56452-8 , p. 139 ff.

- ^ Hans-Ulrich Wehler : Nationality Policy in Yugoslavia. The German minority 1918–1978. Verlag Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1980, ISBN 3-525-01322-1 , p. 13f. And Arnold Suppan : Yugoslavia and Austria 1918–1938. Bilateral foreign policy in the European environment. Verlag für Geschichte und Politik, Vienna 1996, ISBN 3-486-56166-9 , p. 493 f.

- ^ A b Petra Rehder: Slovenia. CH Beck, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-406-39879-0 , p. 125.

- ↑ Robert A. Kann : The Habsburg Monarchy and the Problem of the Supranational State. In: Adam Wandruszka , Walter Urbanitsch (ed.): The Habsburg Monarchy 1848–1918 . Volume 2: Administration and Legal . Vienna 1975, ISBN 3-7001-0081-7 , pp. 1–56, pp. 47 ff.

- ↑ Götz Aly : Final Solution. Peoples' displacement and the murder of European Jews. Fischer TB, Frankfurt am Main 1998, ISBN 3-596-14067-6 , p. 286.

- ↑ Tamara Griesser-Pečar: The torn people. Slovenia 1941-1946. Occupation, collaboration, civil war, revolution . Böhlau Verlag, Vienna 2002. Chapter “The Yugoslav Army at Home (Jugoslovanska vojska v domovini, JVvD)”, p. 24 ff.

- ^ Stefan Karner : Styria in the 20th century. 2nd Edition. Graz 2005, p. 231.

- ^ Research institute for questions about the Danube region: The Danube region. Vienna 1986, No. 28, p. 183.

- ^ Karl-Peter Schwarz: The gruesome secret of the partisans. In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. April 15, 2009, p. 7.

- ↑ Karl-Peter Schwarz: A one and a half meter thick layer of skeletons. In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. Accessed July 22, 2020.

- ↑ Naming Street After Tito Unconstitutional. In: sloveniatimes. October 5, 2011, accessed July 22, 2020 .

- ↑ a b Tagesschau from September 27, 1989. Tagesschau vor ... (ARD) , February 27, 2012, accessed on September 11, 2016 .

- ^ Petra Rehder: Slovenia. CH Beck, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-406-39879-0 , p. 144.

- ^ A b Andrea Beer: Dispute over Piran Bay: Slovenia is right. In: tagesschau.de. Norddeutscher Rundfunk , June 29, 2017, accessed on April 20, 2020 .

- ^ Marine Strauss: EU court will not intervene in Croatia-Slovenia border dispute . In: Thomson Reuters (ed.): Reuters . January 31, 2020 ( reuters.com [accessed April 20, 2020]).

- ↑ Disempowered Prime Minister: Slovenia's governing coalition is threatened with collapse - Slovenia slides into the government crisis. In: Spiegel online. April 26, 2014.