Claustra Alpium Iuliarum

| The lock in the Julian Alps | |

|---|---|

| Alternative name | Claustra Alpium Iuliarum |

| limes | Italy |

| Dating (occupancy) | 1st to 5th century AD |

| Type | Three-part barrage with watchtowers, burgi and forts |

| unit | a) Auxilia ?, b) Limitanei ? |

| Construction | Stone construction |

| State of preservation | Above ground still largely visible, individual wall sections were preserved, the Lanišče castle was partially rebuilt, a round tower in Ajdovščina was completely preserved. |

| place | Julian Alps and Karst (Slovenia / Croatia) |

| Geographical location | 45 ° 51 '49 " N , 14 ° 6' 42" E |

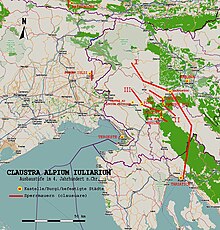

The claustra alpium iuliarum (locks in the Julian Alps ) were a late Roman fastening system at the present territory of Slovenia (Region Upper / Innerkrain ), Croatia ( Rijeka ), Italy (region of Friuli-Venezia Giulia ) and Austria (a small section at Rattendorf in Carinthia ).

The rampart system, more than 80 km long, ran through the karst landscape in western Slovenia and secured the core provinces of the Roman Empire from the 3rd to the 5th century AD. The remains of Claustra are considered to be the largest Roman soil monument in Slovenia in terms of area. Its fortifications were primarily intended to protect an important connection road to Italy, the Via Gemina , and the pass crossing in the Birnbaumer Wald from incursions by potential invaders. They subsequently also secured the gate of Postojna , one of the busiest land connections between the western and eastern parts of the Roman Empire. The wall system was also used several times by ancient authors, such as B. Herodian and Prosper Tiro of Aquitaine mentioned.

Location and road connections

The Claustra Alpium Iuliarum exclusion zone extended over three Roman provinces:

- Noricum-Mediterranum in the northeast,

- Venetia et Histrica in the southwest and

- Dalmatia in the east.

The forts of Claustra were located along the Via Gemina , a military road already built under Augustus through the Karst mountains . a. connected the cities of Emona (Ljubljana), Forum Iulii (Cividale del Friuli) and Tergeste (Trieste) with the Danube port of Siscia in Pannonia and thus shortened the distance to Aquileia by two travel days. In places the road was provided with track grooves and steps for the load carriers and pack animal columns, which were partly carved into the rock or had been removed over time. The center of Claustra was the Ocra Mountains ( Nanos and the surrounding area) with the Ad Pirum fort in the Birnbaumer Wald (Slovenian Hrušica , Italian Selva del Pero ), an approximately 100 km² limestone plateau on the southeastern edge of the Eastern Alps .

In the Tabula Peutingeriana , Ad Pirum is referred to as in alpe Iulia (“in Alpe” is the name of pass stations) and is located on the Hrušica pass between Castra fluvio frigido ( Ajdovščina ) and the hostel ( mansio ) of Longatico (Logatec). In the Itinerarium Burdigalense , a travel guide of an anonymous Christian pilgrim from the year 333, Ad Pirum is listed as a stage stop.

development

The region was inhabited since the Neolithic, as the remains of fortified hill settlements in Logaško suggest. The largest of them was that of Velike Bukve on the tabor of Gornji Logatec. In ancient times, a section of the Amber Road , which connected the Baltic Sea with the trading center Aquileia in northeast Italy, also ran through this region .

The first entrenchments (ramparts and watchtowers) go back to the year 6 AD and were created as a reaction to the great Pannonian uprising , which had massively threatened the heart of the Roman Empire. Since the 1st century AD, there was a post office for the cursus publicus on the Birnbaumer Pass , and from the 2nd century there was also a base for the beneficiaries . A journey on this pass road without escort was obviously a dangerous affair, as the inscription on a tombstone of a centurion of Legio XIII Gemina , Antonius Valentinus, found near Ajdovščina reports. Over the centuries, the region around the Claustra Alpium Iuliarum has also repeatedly been the scene of armed conflicts. The fortifications could only briefly stop the Marcomanni on their march to Aquileia in 169/170 , which they then besieged. The neighboring Opitergium ( Oderzo ) was completely destroyed by them. In response, a temporary military zone, the Praetendura Italiae et Alpium, was set up. Responsible for this was the former consul Quintus Antistius Adventus, who was also in command of the legions newly established in Italy at this time ( Legio II and III Italica ). This military zone included the regio decima , the eastern Friuli and Emona ( Ljubljana ), the southeastern Noricum with the city of Celeia ( Celje ) and the southeast of the Pannonia Inferior around the city of Poetovio ( Ptuj ). It was supposed to secure the road from Aquileia to Emona , which was part of the Amber Road . The military zone was dissolved again in 171. The Alemanni were able during their invasion in 271 claustra overcome apparently without problems, while also penetrate far into northern Italy. The massive final construction to strengthen the barriers began in 284 under Diocletian and Constantine I , the reason for the raid of the Alemanni 13 years earlier.

In the 4th century the troops and fortifications of the ramparts and northern Italy were combined in a separate military district, the Tractus Italiae circa Alpes . The claustra obviously only proved themselves in civil wars. In 351 the usurper Magnentius was able to prevent Constantius II's invasion of Italy by luring his army into an ambush - presumably in the Birnbaumer Wald - and forcing them to retreat to Pannonia after a brief battle near Atrans ( Trojane ). In 394, Theodosius I , emperor in the east of the empire, undertook a campaign with 100,000 men against his western adversary Eugenius , who was supported by the Senate in Rome, among others . Archaeological evidence suggests that Theodosius' army, led by the Magister militum Stilicho , which included a contingent of 20,000 Goths under Alaric , besieged the fortress of Ad Pirum and soon took it. According to another account, the top of the pass had been cleared by the western army before the arrival of the eastern troops. The emperor is said to have spent the night praying in the castle. The subsequent dispute, the Battle of the Frigidus , was fought between Castra fluvio frigido and Ad Pirum . In this battle, which was particularly costly for the West, Theodosius triumphed over his rival and imperial unity was restored for the last time and only for a short time.

During the time of the Great Migration in the early 5th century AD, the barrier system lost its military function and the Birnbaumer Wald was used by various peoples as a gateway to Italy. Alaric in particular had been able to study the terrain and the weaknesses of the defenses thoroughly on the campaign against Eugenius. Because of this, between the years 401 and 409 he and his army of Goths invaded Italy repeatedly over the Birnbaumer Pass ( plundering Rome (410) ). In 452, Attila's Huns also moved across the Birnbaumer forest and destroyed the Ajdovščina castle in the process. Theodoric the Great met with no resistance there either on his conquest of Italy in 489, because Odoacer did not oppose him until the bridge over the Isonzo . Most recently, in 568, the Lombards invaded under Alboin over the Birnbaumer Forest in northern Italy.

Research history

The ruins of the fortress Ad Pirum were excavated by Austrian archaeologists in the interwar period and subsequently conserved by their Italian colleagues. Between 1971 and 1973, further Slovenian-German excavations took place at the top of the pass in the Birnbaum Forest. Above all, part of the inner surface and the east gate of the fort were examined. A gate system of the outer defensive walls in the southeast of the fort was also explored. Most of the militaria finds date from the middle and second half of the 4th century. The most notable of these finds was the fragment of a Roman parade breastplate from the 3rd century that was discovered in the vicinity of the fortress. The burgi of Lanišče and Martinj Hrib as well as a section of rampart near Logatec / Longaticum were excavated and restored by Slovenian archaeologists in the 1970s. Most of the finds from Martinj Hrib date from the late 4th century.

Wall system, forts and burgi

The late antique version of the triple wall system was probably not created in one go, but in several stages of expansion. However, the strategists decided not to build a wall line like Hadrian's Wall in Britain, but instead opted for a system of three consecutive walls with forts and watchtowers at the most endangered passages.

The chain of castles along Via Gemina began in the west at the Ajdovščina fort in the Vipava Valley and ended in the east at Nauportus (today Vrhnika ). The barriers also included fortified places such as Forum Iulii ( Cividale del Friuli , Slov. Čedad ) and Tarsatica ( Rijeka ) and - in addition to the Postojna gate - also secured the chain of hills south of Emona ( Ljubljana ) and the Idrijca valley , where they were reached their end point.

A total of three blocking lines could be identified:

* Listed from east to west

| ON / name | Description / castles / watchtowers |

|---|---|

| Wall I | It ran west of the Logarska basin and marked the line Tarsatica- Idrijcawo valley. A watch / signal tower was erected on its wall at a distance of approx. 100 meters. The southeastern starting point of the rampart system, the Liburnian port city of Tarsatica (Trsat east of Rijeka), a former oppidum of the tribus (tribe) Sergia , was east of the Istria peninsula on the Adriatic coast . It is also mentioned in Pliny the Elder , in the Tabula Peutingeriana and the Itinerarium Antonini . |

| Wall II | He blocked the surrounding area and the passage at Longatico . The Burgi of Martinj Hrib and Lanišče were important military bases on this section of the wall . They probably originated in the Valentine period. The latter monitored a separate road connection to Italy. They were probably destroyed around the year 388 and then given up. |

| Wall III | He secured the section of the valley at the so-called Postonja Gate, the apex of the Via Gemina at 858 m above sea level and the area of the Birnbaumer Forest, which was difficult to access due to its topography alone and could therefore be successfully defended even with a few, well-managed soldiers a rapid advance with a larger army was only possible over the pass road.

Its key position was the castle of Ad Pirum (= "the pear hill" or "near the pear tree") , which was built directly on the pass . The place name was not derived from the tree fruit, but rather from the Greek term for fire, which in turn refers to a watch / signal tower that may have been here before. The oldest finds, however, point to a street station from the 1st or 2nd century AD as the previous building. Ad Pirum was constantly manned by around 100–500 men, its outer ring walls enclosed an area that could offer an additional refuge for several thousand men in an emergency. According to the found coins, the construction of the defensive walls and the fort should have started in the late 3rd century AD. The fort was 250 m long, 75 m wide and surrounded by a 2.70 m wide and 8 m high wall. The east gate was protected by two massive, cantilevered flank towers about 10 m high. The interruption of the series of coins between 388 and 401 suggests that the fort was finally destroyed and abandoned around this time. At the same time, the Castra ad fluvium frigidum / Ajdovščina fort was probably built . Its later name is derived from "ajdi" (= giants), probably an allusion to the late Roman building remains, of which an almost completely preserved round tower can still be seen today. Another important military base on this wall was at Strmica. |

garrison

According to the Notitia Dignitatum , the occupation troops, ramparts and forts belonged to the military district of the Tractus Italiae circa Alpes and were perhaps at times under the command of a Comes Italiae .

Monument protection

Slovenia: The archaeological sites and zones in Slovenia are designated as strictly protected locations by relevant laws and individual ordinances. The export of archaeological objects is prohibited and requires an official license in advance. Unauthorized digging is prohibited. Damage and destruction caused to ancient objects are punishable by imprisonment between five and eight years. (StGB, Article 223). The export of archaeological remains without the approval of the competent authority is punished with a prison sentence of three to five years. (StGB, Article 222) The national monuments are the responsibility of the Slovenian Institute for the Protection of Cultural Heritage (ZVKDS), which is affiliated to the Ministry of Culture.

Croatia: Archaeological finds and sites as well as archaeological zones, landscapes and parts thereof are cultural assets of the Republic of Croatia and enjoy special protection. The Croatian Administrative Authority for Monument Protection in the Ministry of Culture in Zagreb is responsible. The protection is regulated by Act No. 01-081-99-1280 / 2 of June 18, 1999, issued on Article 89 of the Croatian Constitution, with its subsequent additions and amendments. Damage, destruction and theft of cultural property must be reported to the competent authority immediately, but no later than the next day. Unannounced excavations are forbidden, violations of the export regulations are punished as a crime in the most serious case , and in the lightest case as an offense within the meaning of Croatian law.

literature

- Jaroslav Šašel , Peter Petrù: Claustra Alpium Iuliarum. Volume 1: Fontes . Narodni Muzej, Ljubljana 1971.

- Peter Petru: Claustra Alpium Iuliarum and the late Roman defense in Slovenia . In: Arheološki vestnik 29, 1978, pp. 505-509.

- Thilo Ulbert (Ed.): Ad Pirum (Hrušica). Late Roman fortification of the pass in the Julian Alps (= Munich contributions to prehistory and early history. Volume 31). Beck, Munich 1981, ISBN 3-406-07981-4 .

- Marjeta Šašel Kos: Zgodovinska podoba prostora med akvilejo, Jadranom in Sirmijem pri Kasiju Dionu in Herodijanu = A historical outline of the region between Aquilea, the Adriatic, and Sirmium in Cassius Dio and Herodian. Slovenska akademia znanosti in umetnosti Institut za arheologijo, Ljubljana 1986.

- Jana Horvat: Roman Provincial Archeology in Slovenia Following the Year 1965: Settlement and Small Finds. In: Arheolški vestnik 50, 1999, pp. 215-257, zrc-sazu.si (PDF).

- Marko Frelih, Walter Istenic, Mojca Urankar, Donald F. Reindl: Logatec - Longaticum in rimski obrambni sistem Claustra Alpium Iuliarum: s prispevkom o bitki pri reki Frigidus (soča) leta 394. Občina, Turisticno drustvo, 2003, ISBN- 961-91241 0-3 .

- Aleksander Jankovič Potočnik: Utrbe na Slovenskem. Vodnik po utrdbah c Slovenjii in bliznji okolici - ruga dopolnjena izdaja / Slovenian Fortifications. A Guide to Fortifications in Slovenia and Surrounds, Second revised edition. Ljubljana 2008, ISBN 978-961-91721-6-2 .

- Peter Kos: The construction and abandonment of the Claustra Alpium Iuliarum defense system in light of the numismatic material . In: Arheološki vestnik 63, 2012, pp. 265-300 ( digitized version ).

- Andrew G. Poulter: An indefensible frontier: the Claustra Alpium Iuliarum. In: Annual books of the Austrian Archaeological Institute in Vienna. Volume 81, 2012, pp. 97-126 ( preprint ).

- Peter Kos: Ad Pirum (Hrušica) in Claustra Alpium Iuliarum (= Vestnik 26). Zavod za varstvo kulturne dediščine Slovenije, Ljubljana 2014, ISBN 978-961-6902-67-0 , claustra.org (PDF).

- Günther Moosbauer : The forgotten Roman battle. The sensational find on the Harzhorn. CH Beck, Munich 2018, ISBN 978-3-406-72489-3 .

- Mario Zaccaria: Claustra Alpium Iuliarum: a Research Plan. PDF

Web links

- Description and illustrations of Claustra Alpium Iuliarum (English)

- Animation video about the Claustra Alpium Iuliarum on You Tube

- Animation video of the reconstruction of the Ad Pirum fort on You Tube

- Lanišče castle

- Maps and illustrations (Slovenian)

- Poznoantična utrdba Kastra (Ajdovščina) = The late antique Ajdovščina castle (Slovenian)

Remarks

- ^ Charles R. Whittaker: Frontiers of the Roman Empire. A social and economic study. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, London 1997, ISBN 0-8018-5785-6 , p. 197.

- ^ Provincial division according to the Diocletian reforms, early 4th century AD.

- ↑ “... sub Julio Octaviano Caesare Augusto per Alpes Julias iter factum est.” Rufius Festus : Breviarum 7, 51.

- ↑ So in Alpe on the Radstädter Tauern Pass , between Virunum and Iuvavum .

- ↑ Segmentum III, 5th

- ↑ Itinerarium Burdigalense 560, 3 f.

- ↑ Inscriptiones Latinae selectae 2646: "[Valentinus was] slain by muggers in this ominous place in the Julian Alps, [...] in Alpes Iulias loco quod appellatur Scelerata interfecto a latrionibus."

- ↑ G. Moosbauer 2018, p. 26

- ↑ Pedro Barceló : Constantius II and his time. The beginnings of the state church. Klett-Cotta Verlag, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-608-94046-4 , p. 98.

- ↑ Thilo Ulbert 1981, p. 31.

- ↑ Hartmut Leppin : Theodosius the Great, on the way to the Christian empire (= shaping the ancient world ). Primus Verlag, Darmstadt 2003, ISBN 3-89678-471-4 , p. 217.

- ↑ Zosimos : New Story 5, 45, 5.

- ↑ Aleksander Jankovič Potočnik 2008, pp. 21-23.

- ^ Philipp Pröttel : Mediterranean fine ceramics imports from the 2nd to 7th centuries AD in the Upper Adriatic region and in Slovenia. (= Cologne studies on the archeology of the Roman provinces. Volume 2). Verlag M. Leidorf, Espelkamp 1996, p. 136.

- ↑ Peter Petru: Rimsky paradni oklep s Hrusice / Roman parade armor fitting from Hrušica . In: Opuscula Iosepho Kastelic sexagenario dicata (= Situla Bd. 14/15). Ljubljana 1974, pp. 225-237.

- ↑ Aleksander Jankovič Potočnik 2008, pp. 21-23.

- ↑ Marietta Šašel Kos 1986, pp. 195–196 and pp. 203–204.

- ↑ Aleksander Jankovič Potočnik 2008, pp. 21-23.

- ↑ Pliny, naturalis historia 3, 140; Tabula Peutingeriana 5, 1 f .; Itinerarium Antonini 273: Tharsatico .

- ↑ duoviri , decuriones : CIL 3, 3028 .

- ↑ Marjeta Šašel Kos 1986, pp. 195–196 and 203-204; Jana Horvath 1999, pp. 231-232.

- ↑ Michael Mackensen in Thilo Ulbert 1981, pp. 131–152; Marjeta Šašel Kos 1986, pp. 198-207.

- ↑ Aleksander Jankovic Potocnik 2008.

- ↑ Notitia Dignitatum Occ. XXIV.

- ^ Official gazettes for the protection of cultural assets in (Slovene language) ( Memento of the original from June 16, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ The legal regulations on the website of the Croatian Ministry of Culture (in Croatian language).