Limes Britannicus

Limes Britannicus ("British Limes ") is the collective term for those fortifications and ramparts that were supposed to protect the north, the coasts and main traffic routes of Roman-occupied Britain. This section of the Limes existed from the 1st to the 5th century AD and extended to what is now England, Scotland and Wales ( United Kingdom ).

Britain was one of the most restless areas in the European part of the Roman Empire and had to be secured by its army at great expense in terms of personnel and money. Despite the rapid victory over the large tribal associations in the south, the British will not be able to completely break the will to resist for a long time. Nevertheless, the Romans succeeded in further consolidating their rule in the period that followed, although the military stationed there was usually overwhelmed with the simultaneous defense of Britain on three fronts. Especially the incursions of the barbarian peoples from the north of the island repeatedly caused serious problems for Rome. In the west and south-east the British provinces had to be defended against Hibernian and Germanic attackers. Despite all of these adversities, Britain was kept within the Roman Empire for nearly three centuries. In retrospect, historians generally rate Roman rule as positive. For a long time, the Roman troops ensured peace and prosperity on the island. Under the protection of Hadrian's Wall and the natural boundaries formed by the sea coasts to the east, south and west, the regions that are now in England were penetrated by the achievements of Roman civilization. The remains of Hadrian's Wall and the castles on the Saxon coast are the most impressive evidence of Roman rule over Britain to this day.

development

prehistory

In the years 55 and 54 BC A Roman expeditionary army landed in Britain for the first time under Julius Caesar . However, the southeastern tribes avoided direct confrontation. Before Caesar's troops in 54 BC BC moved away from the island again, he concluded a peace treaty with the British tribal leaders. As a result, the south-east of the island came under the influence of Rome from that time on. Weakened by the defeats in free Germania, his successor Augustus later had to drop the plan to conquer Britain. In the autumn of 39 Caligula crossed the Alps with an army in order to continue in the tradition of his ancestors the expansion into Germania and Britain, which was regarded as not yet completed. Even before the planned British campaign, however, his troops mutinied and refused to cross the English Channel. In this context, the sources report that the emperor's orders were sometimes grotesque. To humiliate the soldiers, he had them collect shells on the beaches of the canal, which were to be presented in Rome as "spoils of war". The truth of these absurd processes, which Suetonius describes in this context, remains to be seen. His successor Claudius had little reputation among the troops and was therefore forced - according to the tradition of the emperors - to also gain fame on the battlefield in order to secure his rule over the long term. In the year 43 AD, four legions landed on his behalf on the southeast coast of the island.

Britain under Roman rule

Britain had large deposits of precious metals, fertile soils and extensive forests, which made it economically interesting for the Romans. A large part of the British Isles was conquered by the general Aulus Plautius in the first year of the invasion . He first occupied the territory of the Belgians and their residence in Venta Belgarum (Winchester). The neighboring tribes were given the status of rich clientele. It is possible that Claudius initially only planned to occupy the lowland regions. In the 1st century, the Romans also had no clear idea of how big the island actually was. Britain can be roughly divided into two topographical zones: lowlands and highlands. The lowlands were located near the Gallic coast and were open to contact with the tribes on the continent even before the Roman conquest. It was also much more agriculturally attractive than the highland zone and enjoyed a much milder climate. It is likely that the Romans originally only wanted to annex this region without excluding the rest of the island from their new province. However, the campaign sparked tenacious resistance by the British against the occupiers that lasted for several decades. In the course of the Boudicca uprising , in the reign of Nero , it almost succeeded in driving the Romans back from the island. The Roman sphere of influence was initially repeatedly subject to major shifts in borders. The constantly flaring up battles with the indigenous Celtic tribes in the outskirts of the new province forced the Roman troops to continually occupy new areas in the west and north, in a constant effort to give the Roman dominion permanent and secure borders. The army of Agricola in particular penetrated far into what is now Scotland ( Caledonia ) in 80 AD (after its victory in the battle of Mons Graupius ) . " Perdomita Britannia ", "All of Britain was occupied", wrote Agricola's son-in-law, the historian Tacitus, and added: "... et statim omissa ", "... and was immediately given up". After the permanent occupation of the Highlands failed, the army withdrew to the Stanegate line by 120 AD. Possibly the triumphal arch built in Richborough was supposed to commemorate Agricola's victories. Most of the troops deployed in Britain had to continue to be stationed in the north.

To protect against raids by pirates from Ireland ( Hibernia ), a powerful protection force was also required for the west coast. The regions in present-day Cumbria and Lancashire in particular suffered time and again from raids by the Irish. The Romans had probably already explored the Irish island in detail. Certainly there had been intensive political and economic contacts between the Britons and their western neighbors since pre-Roman times, which the Romans probably took advantage of. Roman artifacts have been recovered in Drumanagh , a little north of Dublin , suggesting that there may have been a trading post here, where Roman ships must have docked. The writings of the Roman authors Juvenal and Tacitus (1st and 2nd centuries AD) provide evidence of limited Roman military action in Ireland. Apparently detailed plans for a landing on the island already existed. However, the driving force behind the Roman conquests of the early imperial era was not just lust for power. Two important questions were usually in the foreground for the strategists: Was there something valuable to be found in the target area - such as? B. rich mineral resources - or did the peoples living there pose an existential threat to the Roman Empire? Neither was the case in resource-poor Ireland. Its quarreling tribes were never really a serious military threat to the Empire. That is why the Romans finally rejected their plans for a logistically very complex and therefore costly conquest of Hibernia.

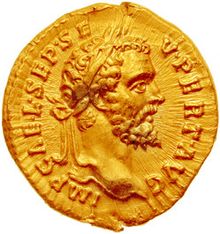

Even under Hadrian's rule, Britain was still not a fully pacified province. Coin issues during this period identify Britain as "in constant defense". In the outskirts of the island, the pre-Roman tribal societies were able to hold their own. The greatest danger always came from the Picts , who settled across the Scottish rivers Forth and Clyde. Between them and the wall lived four other Celtic tribal groups ( Votadini , Selgovaen, Damnonii and Novantae ), whose settlement area, the Central Lowlands, also sought to incorporate Rome in order to neutralize their fighting power and to be able to use the farmland. For this purpose, street forts were built to secure the Roman claims. From 122 the northern border was secured with Hadrian's Wall. The circumnavigation of the wall on both sides was much more difficult to prevent. The barriers built a little later on the Cumbrian coast were supposed to prevent the wall from being bypassed, at least in the west. Under Hadrian, the three legionary camps were also rebuilt in stone. In 140 AD, the Roman troops attacked the Caledonians again and built a new barrier further north, the Antonine Wall . However, this was given up again around 160 AD. 155 to 158 there was a revolt in Britain, which inflicted heavy losses on the legions there. This had to be compensated for by soldiers from the Rhine-Germanic provinces. At the end of the 2nd century, seafaring Germanic peoples from the continent began to threaten the Angles , Saxons and Franks , the Gallic and British coasts with their first raids. In the course of the civil war after the elevation of Septimius Severus to emperor, his rival Clodius Albinus crossed the continent with the British army in 197, but suffered a crushing defeat against Severus' troops in the battle of Lugdunum (Lyon).

In the 3rd century, Roman Britain was undergoing profound changes. After his soldiers returned, the Picts first had to be driven out again. They had taken advantage of their absence for extensive raids. Then Septimius Severus ordered a large-scale punitive expedition against the tribes north of Hadrian's Wall and in the course of this - but only for a short time - occupied the Antonine Wall again. In contrast to the other provinces, it was apparently stable and calm again in Britain afterwards. But from 260 to 274 the British provinces, together with Gaul and Hispania, joined the " Gallic Empire " of the usurper Postumus . Another secession of the island by the admiral of the British fleet, Carausius (287–296), suggests that Roman power there was perceived as weaker and weaker. Carausius used the increasing neglect by Rome to found his own empire, consisting of Britain and a narrow strip of coast around the port city of Gesoriacum in northern Gaul. However, he and his successor Allectus failed because of the counter-offensive of Rome, commanded by Constantius Chlorus , which soon brought down the Gallo-British Empire.

In the late 3rd and 4th centuries the security situation on the continent worsened, as the pressure of the barbarian tribes on the borders on the Rhine and Danube did not ease. Their island location did not really protect the British provinces. Especially the flat east coast with its numerous river mouths was ideal for invaders to land. Hadrian's Wall in the north also proved to be ineffective in warding off barbarians. From the 4th century onwards, Britain was again increasingly the target of attacks by the Saxons, Picts and Skots . The latter circumnavigated Hadrian's Wall in 360, went ashore far to the south and reached the gates of Londinium . The population on the coast of Cumbria could mostly be warned in time by the crews of the watchtowers and small forts located there. Due to the precarious security situation in the rest of the empire, more and more units were withdrawn from the island, so that the British provinces were finally defended almost exclusively by the locally raised auxiliary troops or newly recruited Germanic mercenaries. The British historian Guy Halsall argues that Anglo-Saxon mercenaries came to Britain as foederati (allies) in the course of the usurpation of Magnus Maximus . He may have recruited them as auxiliary troops in order to be able to defend the island effectively even in his absence. At the end of the 4th century, the Roman troops withdrew from Wales, which is why raids and settlement activities by the Irish increased considerably. Hadrian's Wall, too, had to be largely abandoned around 400 due to a lack of soldiers. From this point on, regional rulers or warlords with their own private armies ( bucellari ) increasingly took control of the British provinces. Most of the units of the mobile field army were posted in 401/402 to defend Italy against the Visigoths of Alaric from Britain.

After several barbarian tribes crossed the Rhine border in Gaul in 406 , contact between Britain and the western Roman central government in Ravenna broke off. The soldiers thereupon - presumably pushed by the local upper class - proclaimed three of their own emperors in quick succession, 407 of whom the commander-in-chief of the provincial army, Constantine, finally prevailed. He wanted to take advantage of the political and military chaos in Gaul after the barbarian invasion to strengthen his power and crossed the English Channel with the troops who were devoted to him. Thereupon the Romano-British broke away from him, presumably there was an uprising against the governors appointed by him. Around the year 410 the last units of the mobile field army were probably withdrawn from the island, that was in fact the end of the more than 300-year Roman rule over Britain. After Constantine's death in Gaul, Rome never again succeeded in gaining a foothold in Britain. The historian Prokopios of Caesarea later reported that from this time it was under the rule of tyrants .

Apparently afterwards Anglo-Saxons were recruited from the continent by the Romano-British civitas as reinforcements in order to be able to defend themselves more effectively against the constant attacks. While some researchers assume that some of them came to Britain as mercenaries around 380, the majority now assume that this did not happen until around 440. However, they soon rose up against their masters, as they were supposedly insufficiently cared for by them. Their leaders then established their own independent kingdoms, which quickly expanded west and north. Many regions of Britain continued to be administered according to the Roman model even after the retreat of Rome, but this practice soon dissolved due to the constant advance of the Anglo-Saxon renegades . With the disintegration of the old administrative districts into independent small kingdoms, the jointly maintained Roman provincial army also disappeared.

Development of the Limes

Most of the castles in Britain were founded in the 1st and 2nd centuries AD. Some were only used for a short time, others were more or less permanent or occupied for a long time. The early forts were built using the wood and earth technique. From the middle of the second century AD, they were gradually replaced by stone structures. Roman forts are rare in the interior of the island, south of the Severn-Trent line there were hardly any.

1st century

North and midlands

Four years after the Roman invasion, the conquered territory stretched roughly as far as the Exeter ( Isca Dumnoniorum ) - Lincoln ( Lindum Colonia ) line , an important inter-British transport hub. Around 55 AD the main camp of the Legio II Augusta was set up in Isca Dumnoniorum . This was given up around 75 AD and the place advanced to the civitas of the Dumnonians . The city of Lincoln was first the headquarters of the Legio IX Hispana and was elevated to Colonia at the end of Domitian's reign . It was on the Witham River , another major transportation route. A bridge that spanned the river probably also existed near the city. From north to south, " Ermine Street " connected London ( Londinium ) with the legionary camp of York ( Eburacum ). The " Fosse Way " coming from the west, from the Welsh legionary base in Exeter, one of the main traffic routes of Roman Britain, also ended in Lincoln. Furthermore, from there a road led east to the coast of the English Channel. A first boundary line to the north and west of the island was marked by watchtowers and forts along the Fosse Way. This leads some historians to assume that it served as a Limes in the first years of the Roman occupation. However, it is more likely that the border between Roman and Celtic Britain fluctuated over and over again during this period. In Eburacum in 71 AD the Legio VIIII Hispana built a wood-earth legionary camp to secure the northern region. When Domitian withdrew the Legio II Augusta and most of the auxiliary units from the Scottish lowlands for his Dacer war in 87 AD, this too could no longer be held due to a lack of soldiers. The northern border was taken back to the Tyne - Solway Firth line , a chain of fortifications on Stanegatestrasse . After 100 AD the last forts in the Lowlands were abandoned - with a few exceptions .

The campaigns of Agricola

After the defeat of the Welsh tribes joined an army under the command of the governor Gnaeus Julius Agricola in the settlement areas of the considered particularly warlike Piktenstämme before. In 79 his soldiers reached the Tanaus (or Taus ; its location is unknown today, perhaps the Firth of Tay ) and founded some forts there. Since they were equipped with supplies for a whole year, they could withstand long sieges, even over the winter. In the year 80, Agricola further secured its conquests and built a number of forts for their defense on an isthmus where the inlets known by Tacitus as Clota ( Firth of Clyde ) and Bodotria ( Firth of Forth ) cut deep into the island . He even thought of the conquest of Hibernia (Ireland) and for this purpose he gathered his troops on the coast of the Irish Sea . The further advance northward took place in AD 81, when Agricola apparently advanced across the Firth of Clyde on the west coast of Britain against the resistance of previously unknown tribes. In 82 he advanced with his soldiers and a naval formation along the east coast of Scotland in the regions north of the Firth of Forth. For this purpose, another legion camp was built near Inchtuthil ( Pinnata Castra ). Subsequently, he tried to secure the north with further fortifications on the so-called Gask Ridge (in Perthshire , the border line to the Highlands ). Agricola had its forts and streets built mainly in the Selgovae settlement area . No military security took place in the tribal areas of the Novantae , Damnonii and Votadini , in which Rome apparently had no interest. After Agricola was recalled by the emperor in 84, construction work on the Inchtuthil camp was stopped and the fortifications along the Gask Ridge abandoned. Rome apparently contented itself with a formal submission of the tribes. The expenditures for military equipment and logistics and the losses suffered in this endless war were probably not in a reasonable proportion to the profit made. After his recall, the harsh climatic and poorly productive Caledonia was again left to its own devices and the Romans limited themselves to securing the most fertile and economically attractive regions of the island. The troops bound in Britain were now much more urgently needed to defend themselves against Teutons and Dacians on the Rhine and Danube.

west

The occupation of the western outskirts of Britain was largely over in 52 with the victory over the Silurian tribe . From 74/75 AD Isca Silurum (Caerlon) became the new headquarters of the Legio II Augusta. The Silurians were only finally overthrown in 78 through several campaigns led by Sextus Iulius Frontinus . His successor Agricola subdued at the beginning of the year 79, finally, the ordovices and occupied the British as the holy island applicable Mona , a center of the Druid cult . To consolidate Roman rule, Agricola had in AD 77 or 78 a. a. also set up auxiliary camps on the Welsh coast such as those of Canovium (Caerhun) and Segontium (Caernavon). After the legionary camp in Inchtuthil had been cleared, the Legio XX Valeria Victrix stationed there was relocated to the Deva ( Chester ) camp originally built by the Legio II Adiutrix in 88 . The Legion later replaced the wood and earth fort with a stone warehouse and operated a lead mine there.

southeast

After the Roman invasion , a first legion camp was established near the city of Camulodunum around 43-44 AD , in which the Legio XX Valeria Victrix and auxiliary troops were stationed. However, its crew was detached from Publius Ostorius Scapula to Glevum ( Gloucester ) in Wales in the winter of 48-49 AD and the fortifications in Camulodunum razed. The camp was left to civilians and legionary veterans and turned into a colony .

2nd century

north

At the transition from the 1st to the 2nd century AD, the Stanegate and the forts and watchtowers lined up on it marked the northern border of the Roman domain. In contrast to other limits in the Roman Empire, there was no natural barrier such as B. a wide river that crossed the whole island and whose banks could be fortified relatively easily against the constant attacks and raids of the northern tribes. Therefore the Romans were forced to build artificial barriers there. In doing so, they secured the isthmus between the mouth of the Tyne and Solway Firth ( Hadrian's Wall ) and later also the isthmus between the Firth of Forth and Firth of Clyde ( Antonine Wall ). Around 108 the Eburacum camp was rebuilt in Stein. The Legio VI Victrix has stood here since 120 . In the years 139 to 141 there were again major clashes with the Caledonian tribes. In response, Rome invaded the Lowlands again. At 155 they withdrew from the Antonine Wall, only to reoccupy it a short time later. Because between 155 and 158 serious unrest broke out in the north. The legion there had to be increased with contingents from the Germanic provinces. In 163 the Antonine Wall was finally abandoned and Hadrian's Wall was manned again and - where necessary - repaired. Most of the passages of the mile fort in the north were walled up and the dams over the ditch in front of the building were removed.

West and southeast

Defense and control on the coasts in the west and south-east were also carried out by means of forts, watchtowers and signal towers and along the main roads inland. The majority of the provincial troops were also stationed in such forts, small forts and watchtowers. In the event of an emergency, they received support from the legions , which were now concentrated in the island's three major military centers. These legionary camps were connected by a well-developed road network with all regions of the island occupied by the Romans. The legionary camps at Lincoln and Glouchester were abandoned and converted to veteran colonies.

3rd century

north

At the end of his reign, in the early 3rd century, led the already hard at the gout ill Septimius Severus and his sons Caracalla and Geta a costly campaign in the tribal areas of Caledonii and Maeatae north of the Wall. Caracalla received the supreme command of the army. Geta, on the other hand, received no command, but took on purely civilian tasks. A large number of military buildings along Hadrian's Wall were repaired for this purpose, and the demolition of watchtowers and the downsizing of some forts may have been ordered during this period. Between 209 and 210 the Roman army advanced far to the north of the island to the Moray Firth with great losses . The Antonine Wall was also occupied again for a short time. A peace treaty was finally imposed on the Pict tribes. However, this did not offer a permanent solution. Nevertheless, both sons took on the winning name Britannicus maximus , which their father also used. Severus died on February 4, 211 in Eburacum . From 287 to 296, during the usurpation of Carausius , Hadrian's Wall was again dilapidated and was partially destroyed in combat operations. At the same time, Carausius successfully defended his island kingdom against barbarian incursions. Hadrian's Wall was repaired on his behalf in order to secure the north more effectively against Picts and Scots. As in his earlier actions against Franconian pirates, Carausius probably rebuilt diplomatic relations with the northern barbarians, so his military successes there may also be partly due to his good contacts with their leaders. Carausius' successor, Allectus , withdrew a large part of the ramparts to defend the Channel coast against Constantius Chlorus . In the late 3rd century, however , the Picts and Scots changed their tactics and united in a concerted attack on the British provinces. The Picts did not attack Hadrian's Wall head-on - as is usually the case - but bypassed it by sea. Then they invaded the Roman provinces on the southeast coast. The Scots' predatory fleet landed on the west coast and plundered the Provençals there. After the overthrow of the usurper Allectus, immediately thereafter, Chlorus led a retaliatory campaign against the invaders, marched in the course of this with his troops into their settlement areas north of Hadrian's Wall and devastated them. He was accompanied by his son Constantine . Constantius is likely to have successfully completed the fighting quickly, in January 306 he was proclaimed the "second winner of Britain". But in the same year Constantius died in Eburacum . There Constantine was unceremoniously elevated to Caesar of the West by the soldiers . At the turn of the 4th century the northern border was stable again, but still required strong troops to defend it.

west

The position of the Roman emperors was particularly endangered by usurpations by the legion commanders (see Imperial Crisis of the 3rd Century ). Some of the rebels also came from Britain. In order to be able to muster enough soldiers for their march to Rome, they reduced the British garrisons each time far beyond what was justifiable. The forts in the west were always the first to surrender their crews, as this region was viewed as negligible due to its peripheral location and low economic importance. Even the advance into Scotland under Antoninus Pius led to a considerable reduction in troops in Wales. Only a few forts such as Segontium on the northwest coast remained occupied to keep the Celtic tribes living there under control. In the early third century the Legio II Augusta returned to Caerleon after a lengthy campaign, but the number of Roman troops in Wales remained very low. In the late third century, the coasts there were increasingly threatened by Irish and Scottish raiders. Most of their robbery ships entered the Bristol Channel , a bay between the headland of south-west England and southern Wales. From there they advanced to the richest regions of Britain, the Cotswolds and Wiltshire . A new fort was built in Cardiff to defend against them. Others that already existed were repaired. Nevertheless, the border here became more and more permeable, as the severely decimated protection force could no longer drive the Irish new settlers from the coastal regions.

southeast

On the south-east coast they also made do with forts and watchtowers to fend off migration and raids from Franks, Angles and Saxony. Attempts were made to master the Germanic looters, who had been invading from the sea since about 270, with partly newly built, strongly fortified fortresses. In his chronicle from the second half of the 4th century, Eutrop reports that the commander of the Classis Britannica , Carausius, was commissioned around 285 AD to take action against Frankish and Saxon pirates in the English Channel. The constant raids on the local coasts hindered maritime traffic and, above all, the safe transfer of goods and precious metals to Gaul and Rome . The ramified river system of Britain enabled the Germanic invaders to quickly penetrate the interior of the island with their small, shallow boats. As a countermeasure, the Roman administration set up a separate military district on both sides of the English Channel. These strategically important fortresses and naval stations, well manned during Carausius' short-lived British Empire with its most loyal officers and soldiers, were just as good at repelling Roman invaders. However, the exact date of their creation is in the dark. The already difficult military situation in Britain worsened nonetheless. The army command there had to counter the new threat effectively without having a sufficient number of soldiers available. She was therefore forced to withdraw troops from less endangered or economically unimportant areas of the island.

4th century

north

The Eburacum , which has been strongly influenced by the military since its foundation, maintained its status as the metropolis of the north in the fourth century. In the early 4th century, the Legio VI Victrix undertook major renovations at their main camp. The fortifications and towers were strengthened and other buildings like the Principia were repaired. In 368 the general Flavius Theodosius landed on behalf of Emperor Valentinian I in Britain, where he first defeated the uprising of Valentinus, then a "barbaric conspiracy" of Picts, Scots and Anglo-Saxons and secured Hadrian's Wall again. The two commanders of the provincial army were also killed in the fighting.

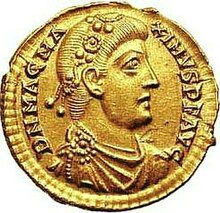

In 383 the acting commander in chief of the provincial army ( Comes Britanniarum in praesenti ), Magnus Maximus , was proclaimed emperor by his troops. The rebellion is said to have been triggered by growing anger among the British military over the Emperor of the West, Gratian , who allegedly preferred Alan warriors to Roman soldiers. The decisive factor, however, is likely to have been that the British troops, which were involved in constant defensive battles with the Picts, Skots and Irish, felt increasingly abandoned by the emperor. It was typical for troops constantly in combat that over time they developed a great desire to be “close to the emperor”. But Gratian was already busy dealing with other crises in the empire. That is why the Romano-British soldiers unceremoniously elevated their general to emperor. Maximus also enlisted a large part of the garrison units stationed on the northern border in his army for his subsequent campaign in Gaul. As a result, Hadrian's Wall was likely to have been almost unguarded from this point onwards and ceased to be a coherent and uniformly organized border security system. After the usurper's violent end, many of his soldiers did not return to Britain, but instead settled on the west coast of Gaul, in Bretannia , what is now Brittany . The fact is that Maximus' continental campaign withdrew a large part of the Roman troops from the island. However, since Roman units were relocated to Britain towards the end of the 4th century (see below), the province could not have been given up at the time of its usurpation.

In 398/399 another Roman army was sent to Britain. The panegyric Claudian reports that the Western Roman magister militum , Stilicho , led a campaign against the Picts and Scots on Hadrian's Wall. Stilicho apparently subordinated the Comes Britanniarum to nine units of the Comitatenses . In 402, however, most of these soldiers were withdrawn to use them in Italy against the renegade Visigoth army of Alaric . Around this time the praepositus Justinian had a tower in the Ravenscar Castle renewed and on this occasion the last known Roman building inscription in Britain was placed.

west

In the fourth century, Cardiff, Caernarfon, Holyhead and Caerhun were particularly hard hit by Irish pirate attacks. It is believed that Magnus Maximus was responsible for the final withdrawal of most of the Roman troops from Wales. In Welsh lore, it is reported that Maximus reorganized the island's defense before leaving for Gaul. He divided Wales into new military districts, which he then subordinated either to a regional tribal chief or officers of the Limitanei . It is unclear when the Legion was withdrawn from the Caerleon camp. Maybe at the end of the third or around the middle of the fourth century. Coin finds with minted dates up to 370 show a - possibly only civil - settlement continuity up to this time. The final coin comes from the reign of Theodosius (388–395). The Chester legionary camp was also likely to have been evacuated during this period.

southeast

In the south-east of Britain, from the turn of the 3rd to the 4th century, Frankish and Saxon pirates were up to mischief. In the middle of the 4th century, the responsibility for securing this stretch of coast lay with a Comes . In 367 several barbarian peoples invaded Britain at the same time . As a result, the units of the provincial armed forces were either wiped out or blown up. Their commanders-in-chief were also killed, including the "Count of the Coastal Regions". His area of responsibility must then have been divided into three military districts - by 395 at the latest. This also wanted to prevent a military leader from getting too many units under his command and thus a rebellion (such as the usurpation of Carausius) could repeat itself.

5th century

north

In the forts on Hadrian's Wall, no more Roman coins could be found in the excavation layers after 407. With the - presumably - between 407 and 410 withdrawal of the British field army by the usurper Constantine III. The garrisons on the Wall probably lost some soldiers too. But Constantine was probably followed by very few fighters from the north, as most of them were born there and ran their own farms with their families at the stations. According to the Notitia Dignitatum , which was last updated around 420 , the wall seems to have been guarded by regular limitanei at least until the early 5th century . They were under the command of the Dux Britanniarum , which probably still had considerable material and military resources. Before he left Britain, Magnus Maximus presumably appointed Coelius commander in chief on the northern border; he should have been the last military commander appointed there by the Romans. John Morris suspects that he was the legendary Coel Hen . Archaeological finds show that some of the fortifications were still inhabited by the descendants of Roman soldiers until the first half of the 5th century. The Birdoswald Fort was even inhabited until the early Middle Ages. Most of them turned into defensive villages ( oppida ) in the course of time or were removed for the extraction of building material; some mile forts were u. a. used as cattle pen. The southeast was still protected from attacks by the Picts and Skots by the troops of the Dux . The administrative districts of the late Roman provinces disintegrated towards the middle of the fifth century through the division of inheritance into independent small kingdoms, which is why Eburacum finally received no more material or financial donations from the south. Coel Hen appears to have wielded far greater power in the northern half of Britain than the previous incumbents. He could represent a transition between a late Roman military official and a regional ruler in an increasingly independent kingdom. Coel then became, according to a Welsh tradition, the ancestor of all the Celto-British kings in this region. Eburacum advanced to become the metropolis of the Celto-British kingdom of Ebrauc . The consequence of this was that intruders were only fought if they threatened your own territory.

west

Since there was no longer any central power in the south-east, the local commanders also let the Irish take their hand at their conquest on the Welsh coast and in the remote regions of Cornwall and Devon . At that time, only larger Romano-British settlements such as Carmarthen and Caerwent are likely to have had a garrison in Wales. After the collapse of the Roman administration in the early fifth century, the old tribal societies revived and the West also quickly disintegrated into independent, constantly warring petty kingdoms. It was only around the larger cities of Chester, Wroxeter, Glouchester and Caerlon that a certain amount of Roman way of life could still be maintained.

southeast

Even the Comes of the Saxon coast did not join Constantine's march to Gaul with his troops. He was probably able to maintain his defense organization until the beginning of the 5th century. This part of Britain had the greatest number of cities and the most developed production of goods. It is believed that military activity in the castles there continued well beyond the early 5th century. The Saxon coastal forts were no longer supplied from state magazines. Their crews, which were mostly made up of Germanic tribes, ran mostly small farms with their families - as on Hadrian's Wall - and produced most of what they needed to live themselves. When the pressure of the Anglo-Saxons to migrate to Britain grew steadily and they slowly began to appropriate the fertile lowlands as well, the Romano-British fled a. a. also in the forts on the Saxon coast, most of which were probably still intact. However, this only temporarily protected them from the invaders. One of them, Anderitum , was besieged and stormed in 491 by the Anglo-Saxons under the command of the first King of Sussex , Ælle (477-514) and his son Cissa. The defenders were killed down to the last man. This is one of the rare surviving reports from the Migration Period about the successful siege of a fortified Romano-British settlement by the new immigrants. There are further indications in Gallic chronicles that the island came more and more under Anglo-Saxon rule after 440/441 at the latest - probably triggered by a rebellion of the foederati recruited by the Provençals .

troops

When the resistance largely subsided towards the end of the 1st century - at least in the south - Britain nevertheless stood out from all other provinces for the next 300 years due to its massive military presence. By the middle of the 2nd century, 10-12% of the Roman army was stationed there, although its area was only 4% of the entire empire. Legions, auxiliary cohorts and fleet were commanded by the incumbent provincial governors.

At the time of its peak, the Roman army in Britain (Exercitus Britannicus) numbered probably 35,000 to 40,000 men. This made it the largest standing association in the Roman army. 122 soldiers from 13 ales and 37 cohorts, a total of 50 different auxiliary units, have been rewarded with citizenship. Two decades earlier, 103 and 105, two constitutions were issued for soldiers from different groups of units. Soldiers from once four, once two Alen and eleven cohorts each were privileged, the troop lists did not overlap. So at that time there were already at least six Alen and at least 22 cohorts on the island. Jarrett assumes a strength of the exercitus under Hadrian of 15 ales and 43 cohorts, of which nine ales and 35 cohorts are still detectable at the beginning of the 3rd century AD. Since there were always three legions stationed in Britain during this time, this results in a ratio of 3-5 ales and 11-15 cohorts per legion. In the case of forts built later on the Saxon coast, however, it is less clear who was directly involved in their construction. From the 3rd century onwards, the number of men in the Roman army in Britain was reduced further, so that by the end of the century (around 210 AD) there was probably only a little more than half left. It is also crucial that the composition of the troops changed during this time and that the number of available army craftsmen must also have decreased from the middle of the 3rd century. In spite of such bloodletting, the Roman army in Britain was not yet overstretched at this point, its provinces had largely remained unmolested by the sometimes violent conflicts that raged in the rest of the empire.

Such a high number of soldiers can only partly be explained by the stubborn resistance of the British against the Roman occupation. It is conceivable that Britain was viewed as an ideal location due to its peripheral location, e.g. B. to permanently isolate and employ some of the potentially troubled legions. Their commanders, the Legati , have also been reprimanded several times for their seditious behavior. Britain is surrounded by water. So it wasn't that easy to start a rebellion against the Emperor from there. Nevertheless, in AD 185, British Lanciarii (javelin throwers) marched to the gates of Rome in 1500 and murdered the Praetorian prefect of Commodus , Tigidius Perennis, and his family. How the soldiers managed to penetrate unhindered into the heart of the empire without the imperial court taking appropriate countermeasures remains an unsolved mystery to this day. Presumably Rome was firmly convinced that the troops in Britain were too far away to pose a serious threat. During the era of the Gallic and British Empire in the 3rd century, the British troops always stood on the side of usurpers.

Like most of the other provinces of Rome, Britain was kept under control by threats or use of force when necessary. The army should not primarily protect the British from their enemies, but rather intimidate or control them and ensure that a maximum of taxes reliably flowed into the Reich treasury every year. The military administration also recorded where and how many people lived there, their travel movements and what property they had to show. With this information, the Romans were able to tax them even higher and more efficiently than they had ever been before. But the remuneration and equipment of the provincial armed forces probably devoured a large part of the tax revenue.

Legions

Four legions remained in Britain for the first four decades after the invasion of 43. Thereafter, by the end of Rome's rule in the early 5th century, their number dropped to three. Their headquarters were in

- Eburacum / York,

- Isca Silurum / Caerlon and

- Deva / Chester .

Taken together, their total strength was around 15,000 men.

| Time position | legion | Locations / missions |

|---|---|---|

| 1st to 5th century | Legio II Augusta | One of the legions that it can be safely said belonged to Claudius' invading army. The Legio secunda Augusta was involved in 30 combat operations in Britain (their greatest success was the siege and storming of the fortress of Maiden Hill), they conquered 20 villages and also landed on the Isle of Wight . In 43 she was commanded by the later Emperor Vespasian during a campaign in southwestern Britain . She had also played an important role several times in the crushing of subsequent revolts by the British tribes. After the occupation of the south, the legion was divided into vexillations and initially stationed in the south-west of the island. She stood u. a. in Silchester and from 49 AD in Dorchester and Lake Farm near Wimborne until she was transferred to the Exeter legionary camp in 55 AD . Around 74 on the banks of the Usk, initially only a temporary camp, but a few months later (74/75) a new one in Caerleon (Welsh: "the fortress of the Legion") was built. It remained their headquarters until the early 3rd century AD. At times up to 5000 men were stationed here. In the 2nd century their legionaries took part in the construction of Hadrian's and Antonine walls. They preferred to erect the mile fort on Hadrian's Wall and various buildings in Corbridge . The Legion was used again under Septimius Severus, 207, for renovation and repair work on the wall. In the course of the campaign against the Caledonian tribes, the unit shared a fort near Carpow on the Tay with the Legio VI Victrix after 208 and stayed there until the occupied territories in Caledonia were given up again under Severus Alexander . After that, the Legion was probably used increasingly in Kent in coastal defense. In late antiquity it was in Richborough , but the Saxon coastal fort there was only a fraction of the size of Caerleon. The legion's manpower must have been considerably smaller than it was in the middle of the imperial era. The Legio II Britannica attested for the 4th century was possibly pulled out of the Legio II Augusta in the time of Carausius . |

| 1st century | Legio II Adiutrix Pia Fidelis | Stationed in Britain since 60 or 71. But she probably came to Britain with the army of Petillius Cerialis . Since that time she was in Lincoln. It is uncertain whether the Legio secunda Adiutrix was completely relocated to the west of Chester in the 80s or only one of its vexillations. The main task of the Legion was to support Legio IX and XX during their campaigns in the north in the 70s and 80s. After the Romans withdrew from Scotland, it was withdrawn from Britain in 87. |

| 2nd to 5th century | Legio VI Victrix Pia Fidelis | She had been in Britain since 121 and had her headquarters in Eburacum (York). From 122 the legionaries were used in the construction of Hadrian's Wall . Their construction phase was between Newcastle upon Tyne and Carlisle . Between 139 and 142 some of her vexillations were entrusted with the construction of the Antonine Wall between Edinburgh and Glasgow . Since 158 the Legio sextae Victrix was busy with the revitalization of Hadrian's Wall in preparation for the retreat from the Antonine Wall. In the period between 175 and 190, a few decades after the Antonine Wall was abandoned, one of its vexillations was at least temporarily stationed in the Castlecary outpost fort. In the late 2nd century one of its vexillations was in Coriosopidum . The prefect Lucius Artorius Castus , perhaps the historical role model for the legendary King Arthur , was in command of the legion between 180 and 230. He probably led a campaign against rebels in Brittany in the late 2nd century with vexillations drawn from all three British legions. Legion inscriptions can be traced back to the beginning of the 5th century AD. Around 402 the rest of the Stilicho Legion was probably withdrawn to defend Italy. It is possible that in post-Roman Britain a militia formed from their veterans still occupied a few forts on Hadrian's Wall. |

| 1st to 2nd century | Legio IX Hispana | Since 30 BC It was first used in Hispania , from 19 BC onwards. BC she was nicknamed Hispana . She probably took part in the Claudius invasion in 43. Their presence on the island has only been reliably proven since the year 60. The last inscription, which mentions the Legio nona Hispana in Britain, dates from the year 108. It was removed from there before 122. |

| 1st century | Legio XIV Gemina Martia Victrix | The Legion arguably also participated in the invasion of 43. Their presence in Britain cannot be proven before 60. She was honored under Nero for her work in suppressing the Boudica uprising . The Legion was moved back to the continent in 69 (Danube Limes). |

| 1st to 3rd century | Legio XX Valeria Victrix | Presumably it was part of the invading army from 43. Before 60 it is epigraphically undetectable in Britain. The honorary title Valeria Victrix was awarded to her for her participation in the suppression of the Boudica uprising. Initially, part of the Legion - together with auxiliaries - was stationed in the Camulodunum camp (Colchester). 48–49 AD she was relocated to Glevum (Gloucester) in Wales. Kingsholm near Gloucester could also be considered as an alternative location. In 57 she was moved to Usk. Shortly after 65 the Legion was posted to Viroconium (Wroxeter) to replace the Legio XIIII Gemina there . The Legion was also temporarily in Carlisle. Around 84 she built the Pinnata Castra (Inchtuthil) camp on the Scottish River Tay. In 88 she was moved to the camp Deva (Chester) built by the Legio II Adiutrix . Between 122 and 125, their legionaries were assigned to build Hadrian's Wall. From 139 to 142 they were also involved in the construction of the Antonine Wall. At 219 there were vexillations in Alauna (Maryport), Netherby and Bewcastle. They also carried out construction work there. The last inscriptions that tell of the Legion date from the 3rd century. Perhaps it was dissolved by Constantius Chlorus after the breaking up of the British special empire . It is also possible that it was withdrawn from Britain by the regent of the west, Stilicho , between 402 or 403. The Legion no longer appears in the Notitia Dignitatum either. In the troop list of the Dux Britanniarum only one Numerus Solensium is given in Maglone , it could have emerged from this legion. |

Auxiliaries

More than half of the Roman occupation forces in Britain were recruited from the auxiliary forces ( auxilia ). Auxiliary units are rarely mentioned in ancient literary sources. The epigraphic evidence of their presence there comes from various sources - including the famous wooden tablets from Vindolanda and military diplomas . The majority of the British occupation force consisted of soldiers - mainly recruited in Spain, Gaul, Lower Germany, Bulgaria and Greece. Their primary task was the guard duty in the border forts. The forts on Hadrian's Wall ( per lineam valli ) were invariably occupied by them. His garrisons totaled around 12,000 men, including the outposts, as an estimate based on the size of the fort shows. That was almost a third of the British auxiliaries. The strength of the auxiliary troops reached their highest level in the 2nd century and at that time probably comprised around 20,000 men. However, it is not possible to give a precise answer to which units are involved. Military diplomas from AD 98, 103, 105, 108, 122, and A.D. 124 show numerous auxiliary units who were in Britain, but they do not record where these troops were garrisoned.

Under Hadrian there were 14 cavalry squadrons ( ala ) and 47 infantry cohorts ( cohortes peditae ) of the auxiliary troops in Britain :

- civium Romanorum = Roman citizens

- equitata = partially mounted

- milliaria = 1000 strong

fleet

The provincial fleet, Classis Britannica , was responsible for the control and surveillance of the waters and coasts around the British island. It had emerged in the 1st century AD from the naval forces used in the invasion. Their units mostly operated in close cooperation with the land forces and also played a key role in supplying the provincial army with the necessary supplies. She played a particularly important role in the forays into the north of the island by Gnaeus Iulius Agricola . Your teams explored the coasts of Ireland and Scotland, circling Britain. With the establishment of the Limes on the Saxon coast in the 3rd century, the fleet regained somewhat greater importance. Vegetius, a chronicler who wrote his works at the end of the 4th century, mentions that the provincial fleet still existed at that time. The main task of their warships was to secure the strategically and economically important passage between the British and Gallic coasts (Dover-Calais). Your main port on the British side was initially probably Portus Dubris / Dobrae (Dover). Under Carausius, the fleet command was temporarily housed in Portus Adurni (Portchester), after which it was relocated to Rutupiae (Richborough).

Late antique military organization

In late antiquity, the military administration was separated from the civil administration throughout the empire and the army was divided into a mobile field army ( Comitatenses ) and a stationary border guard ( Limitanei ). The garrisons of the Saxon coastal fort consisted of infantrymen ( pedes ), some cavalry units ( ala ) and the crews of the canal fleet ( liburnari ). Until the middle of the 3rd century the outpost forts, such as B. Bremenium and Habitancum , occupied with reconnaissance ( exploratores ), which suggests increasingly troubled times. These units were later disbanded because they had actively participated in the barbarian conspiracy of 367. A mobile field army is demonstrable for Britain from 395 onwards. It was supposed to locate, destroy or drive out intruders who had penetrated into the hinterland. The main source for the composition of the late Roman army in Britain is the Notitia Dignitatum Occidentis (Western Empire) - probably last updated around 420 . It is believed that the British troop lists show the inventory around 400. Possibly they were already out of date when they were written, as many units from the Middle Imperial period are still listed in it. On the other hand, the lack of the outpost fort on Hadrian's Wall speaks for its topicality at the time. The legionary camps of Chester and Caerleon are also no longer mentioned in the Notitia . Another indication that the Roman troops from Wales had withdrawn completely by this time. According to ND, the Limitanei in the north and south-east were commanded by a Dux limites and a Comes rei militaris , which in turn were subordinate to the highest-ranking army commander in Britain. As a rule, the period between 409/410 is considered to be the time when the last regular troops of Rome moved away from the island. With the departure of the Comitatenses , the almost 400-year-old Roman military presence in Britain is likely to have come to an end as early as 407. The field army that embarked for Gaul with Constantine was probably a rebellious mercenary force dominated by German warriors, who were only sworn to his person and remained loyal to him as long as he could provide them and their families with all essential goods. Nevertheless, with their departure, the most powerful units of the provincial army must have been withdrawn. Unlike in earlier times, the loyalty of Romano-British soldiers was no longer to the ruling emperor, but primarily to their home provinces or generals. Most of the Limitanei in the north and on the Saxon coast therefore remained in their forts. These units probably only dissolved with the gradual disintegration of the provinces into small kingdoms.

The military leaders and units of the provincial army listed in the Notitia Dignitatum (as of the early 5th century AD)

| Army commander / command area | equestrian | infantry | infantry | infantry |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Comes Britanniarum |

I Ala Herculeae |

Cohors I Vetasiorum |

Numeri Fortensium |

Legio II Augusta |

Limites in Britain

The defense of Roman rule in Britain relied on five chains of fortresses over the centuries:

* Listed from north to south

| Surname | location | description | map |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gask Ridge | This chain of castles and watchtowers was located along two Roman roads in northern Scotland (county of Perthshire ). | Presumably it was created under the Flavians in the late 1st century. It was one of the earliest Roman border fortifications in Britain. However, the fortifications only served to secure supplies for the campaign of Agricola , governor of Britain around 80 AD. As far as we know, the chain of castles extended from the south end of Loch Lomond (Drumquhassle near Drymen ) and Barochan on the Clyde in a north-easterly direction Stracathro. They protected the agriculturally productive coastal strip between Strathallan and Strathearn and also served for reconnaissance, in order to be able to recognize the advance of enemy tribes from the west at an early stage and for the transmission of communications between the coastal strip and the Roman-controlled areas in the south. The Gask Ridge also acted as a base for further advances to the north. Almost each of the forts was positioned at the point where one of the rivers from the highland valleys (Glens) flows into the lowlands. This enabled the main local traffic routes to be monitored. Camps and towers were built using the wood-and-earth technique, were surrounded by one or two trenches and occupied by auxiliary soldiers. The northernmost legion camp in Britain was built in Inchtuthil. Fortresses were also built at strategic positions such as Elginhaugh and Newstead between the Forth and Tyne. So far, three larger forts are known in Ardoch , Strageath and Bertha. There were also smaller fortifications between the forts. Overall, the crews of three or four small forts and 18 watch and signal towers ensured comprehensive surveillance. To prevent surprise attacks from the numerous deeply cut glens of the Highlands, each of them was also secured by watchtowers or small forts (glen blockers). Today remains of some watchtowers and those of a small fort, Kaims Castle, are still visible. Ardoch is one of the best preserved Roman castles in Scotland. | |

| Antonine Wall | This rampart secured the narrowest part of the island, the isthmus between the Firth of Forth and the mouth of the Clyde ( Central Belt ). | Antoninus Pius had this wood-earth wall ( vallum Antonini ) built between 139 and 141. It was topographically more favorable and with a length of 60 km (40.49 Roman miles) it was also much shorter than Hadrian's Wall. In contrast, however, the supply routes lengthened. It consisted of a 3 meter high earth wall on a 4.5 meter wide stone foundation, covered with turf. The parapet consisted of palisades. In the run-up, a 12-meter-wide and 4-meter-deep trench was dug 6 meters from the wall as an approach obstacle. Building inscriptions report that legionaries and auxiliary soldiers were involved in the construction of the wall. He was secured with wood and earth forts of various sizes. Watchtowers at regular intervals between the forts, such as on Hadrian's Wall, were not installed. A total of 15 forts are known that were occupied by auxiliary troops. In front of the wall there were four outpost forts. The approach routes in the hinterland (Central Lowlands) were also secured by fort chains. | |

| Hadrian's Wall | The rampart zone ( vallum Aelium ) extended 113 km along the isthmus between the mouth of the Tyne in the east and the Solway Firth in the west, in the area of the Roman province of Britannia inferior , from late antiquity of the Maxima Caesariensis , which encompassed the whole of northern Britain. | According to the chronicler Aelius Spartianus , the wall was built to "... separate the Romans from the barbarians". Its primary purpose, however, was to control the activities of the indigenous tribes on both sides of the wall, to control the movement of people and to levy taxes on merchandise. The border wall was built at the beginning of the 2nd century in six years. On the west coast of Cumbria, a similar barricade of wood-earth fortifications and palisades was built over a length of 40 km to repel pirate attacks and prevent the wall from being bypassed over the sea. In the eastern part it consisted of a 4.5 m high stone wall (Newcastle uT to the River Irthing), in the western part (to Bowness o. S.) initially only a provisional wood-earth wall. Trenches on the north and south sides ( vallum ) marked the military exclusion zone and served as obstacles to the approach. Later the western section was also expanded in stone. In the east, the stone wall was subsequently extended to Wallsend. A section of the east wall was raised to a width of 3 meters (broad wall). It was reduced to 2.1 meters during construction (narrow wall). 17 cavalry or infantry fort, 80 mile fort (as fortified passages) and 320 watchtowers strengthened the border fortifications. The mile forts were about 1 Roman mile apart. There were two watchtowers in between. They were connected by the military road that ran between the southern trench and the wall in a zone closed to civilians. The most important supply port for the wall garrisons was South Shields at the mouth of the Tyne . At first they were satisfied with accommodating the men in the old forts on Stanegate, but later on it was decided to move all garrisons directly to the wall. Some fortifications were therefore only built after its completion. In the course of time, some forts were added to secure the apron. But most of the Stanegate fort also remained occupied by the military to secure supplies. The garrison garrisons in the Pennine Hills supported the ramparts and the northern outposts . The British resident there had long been subject, their settlements surrounded by numerous forts, nevertheless they tried to evade the permanent control of the Romans. The wall was occupied by Roman troops until the early 5th century. | |

| Stanegate | This road running from east to west ("stone road") lay in the area of the Roman province of Britannia inferior , from late antiquity the Maxima Caesariensis , which encompassed the whole of northern Britain. | The road was laid out during the campaigns of Gnaeus Iulius Agricola and secured at regular intervals by forts and watchtowers. It initially served as a starting point and supply route for his further conquests in Caledonia . It ran mostly in the river valleys of the Tyne Irthing and Eden. The first forts founded by Agricola on Stanegate were still a day's march apart. This was still considered sufficient in the early days of the Roman occupation. The forts of Vindolanda (Chesterholm) and Nether Denton may have been built at the same time as Coriosopitum / Coria (Corbridge) and Luguvalium (Carlisle), between the 1970s and 1980s. In 105 Emperor Trajan moved additional cohorts of auxiliary troops to the Stanegate and a number of new forts were built between Chesterholm, Carlisle and Corbridge. This shortened the distance between the individual camps to about half a day's march. Newly established small forts and watchtowers at good vantage points such as Pike Hill and on the Walltown Crags (later watchtower 45a Walltown of Hadrian's Wall) on both banks of the Irthing further consolidated the fortress line. With the construction of Hadrian's Wall, 122, the Stanegate line lost its border security function. Some of their forts and towers were included in the wall because of their favorable location. | |

| Fosse Way | This road connected the southern Welsh legionary camp Isca Dumnoniorum ( Exeter ) with the Roman colony of Lindum ( Lincoln ). In the 1st century it formed the western border of the Roman sphere of influence in Britain. The name of the street is derived from the Latin fossa (ditch). Presumably a trench had been dug next to the road as a border marker. In this case, however, it was not yet possible to speak of a first "fortified Limes" in the classical sense, since at this time the doctrine of the "empire without borders" ( imperium sine fine ) was still adhered to. | ||

| Saxony coast | This Limes section ( litus saxonicum ) existed from the late 3rd to the early 5th century AD. It extended along the coasts of the provinces of Flavia Caesariensis , Maxima Caesariensis and Britannia prima . | The coasts were controlled and monitored by a chain of watch towers and signal towers and forts. Most of the Saxon coastal forts also served as naval bases. The first camps were probably built on behalf of Probus . These forts were later integrated into the new line of defense. When exactly or on whose occasion it is unknown, this may have happened on behalf of Carausius, who had further signal stations, forts and fortified harbors built from 286 onwards. The army built new forts in exposed coastal areas and especially at river mouths, which were also connected to the military camps and fortified port cities on the Gallic mainland. It is estimated that the construction of this Limes, located in the area between the Wash and the Solent , took almost a century. The coin finds and typology of the Saxon coastal fort also contradict a simultaneous construction of the SK Limes. Only at the end of the 3rd century did a dense network of fortifications, some of them heavily fortified, extend along the south-east coast, which became increasingly important for the defense of the most economically developed regions of Britain due to the steadily increasing raids by Franks and Saxons. You can use them to follow the change from the military architecture of the 2nd century to the much more massive fortress construction from the 3rd century onwards. The forts, which were founded in the late 3rd century, are particularly well preserved. Some of them were used as fortresses until the Middle Ages. Between the coastal fort and the northeast there were numerous smaller bases that were used to transmit communications. It is believed that they were not only pure war ports, but also important links in the supply logistics of the provincial troops. The units stationed there could be relocated quickly if necessary, as they could fall back on the well-developed road network and the fleet. From the early 5th century, some of the forts were transformed into civilian oppida . Their Romano-British residents were soon expelled or assimilated by the Anglo-Saxon immigrants. | |

| West britain | Today's Wales and Cornwall lay on the territory of the Roman province of Britannia superior , from late antiquity on Britannia secunda , which encompassed the whole of western Britain. | To consolidate their rule, the Romans laid a dense road network here, secured by forts. The occupation army for the west of the island consisted at times of around 30,000 men who had to put down the rebellions that flared up there again and again. The interest of Rome in this rough and mountainous country was - apart from the mining of its natural resources - only slight, since there was only little suitable arable land for cultivation and settlement. Most of the Roman remains still visible in Wales today are therefore fortifications. So far, a total of 30 auxiliary forts are known, each only a day's march away from each other. The majority were wood and earth forts and were not occupied for very long, as most of the indigenous tribes gave up their resistance to the Roman occupation in the 2nd century. Some were later rebuilt in stone. Moridunum later turned into a civilian settlement. Two of the three British legionary camps were on Welsh soil (Chester, Caerleon) from which the country was administered. Around 11,000 men were stationed in them. Via well-developed roads they were directly with the most important auxiliary troop camps such as B. Segontium (Caerhun), Canovium (Caerwent) and Moridunum (Carmarthen) connected. |

Timetable

1st century BC BC to 1st century AD:

- 55 BC: Julius Caesar lets his fleet explore the SE coast of Britain.

- 54 BC BC Caesar lands in Britain, but withdraws to the Gallic mainland before the end of the year.

- 27 BC Chr. To 14 AD: Augustus becomes the first emperor of the empire, although his court poets repeatedly report on an allegedly planned conquest of Britain, but this never takes place.

- 41 to 54 AD: the reign of Claudius.

- 43 AD: Claudius sends an invading force to Britain, which within a few years brings the south-east of Britain under their control. Many of the native tribes welcome the Romans and cooperate with them. Others, especially in the west and north of the island, offer strong resistance, but are gradually subjugated.

- 54 to 68 AD: Nero's reign.

- 60 to 61 AD: Outbreak and bloody suppression of the Boudiaca uprising, after that there is no more revolt against Roman rule in the south of the island.

- 72 to 73 AD: Foundation of the Luguvalium (Carlisle) castle , it serves as the basis for the conquest of northern Britain.

- 78 to 84 AD: Agricola's governorship and Roman advance into the north of the island. Agricola defeated a coalition of the northern tribes in the battle of Mons Graupius, afterwards founding of forts and watchtowers on the SE coast of Scotland (Gask Ridge), north of the Forth Line and a legion camp in Inchtuthil.

- AD 86-87: Scottish castles are abandoned and the British legions are reduced from four to three.

2nd century AD:

- 98 to 117 AD: reign of Trajan, wars with the neighboring peoples of the Romans mainly take place on the Danube border and in the east. What happened in Britain during this time is largely unclear, presumably another legion was withdrawn from the island and the remaining crew was repeatedly involved in smaller disputes with the tribes in the north.

- 117-138 AD: Hadrian's reign, he gives up some territories in the east that were conquered by Trajan. Then he traveled to all Roman provinces, ordered numerous reforms there and had the existing borders secured by a limes. At the same time, riots break out again on the northern border of Britain, which will last throughout Hadrian's reign.

- 122 AD: Hadrian visits Britain, Legio VI Victrix is permanently stationed on the island and the construction of Hadrian's Wall ( Vallum Aelium ) is ordered to protect the northern border.

- 138 to 161 AD: reign of Antoninus Pius; in the early stages of his rule, war is likely to break out again with the northern British tribes. As a consequence, the emperor gave up Hadrian's Wall, marched into the Lowlands and had a new border barrier, the Antoninus Wall ( Vallum Antonini ), built further north on the Forth-Clyde line .

- 158 AD: Evidence of extensive renovation work on Hadrian's Wall. The Antoninuswall is either abandoned in the late period of Antoninus Pius' rule - or only on the orders of his successor Marc Aurel (around 163) - and the border troops are drawn back to Hadrian's Wall.

- 161 to 180 AD: Reign of Marc Aurel, heavy fighting with barbarian tribes on the Danube border and the outbreak of the Antonine plague. Riots break out again in Britain.

- 180 to 192 AD: reign of Commodus, barbarian invasion of northern Great Britain, during which one of the legionaries is killed. A coin emission of 184 celebrates the victory over the invaders.

3rd century AD:

- 197 to 211 AD: Reign of Septimius Severus, who emerged victorious from a civil war during which his greatest adversary, the governor of Britain Clodius Albinus, was killed in the battle of Lugdunum . Then again serious unrest in Northern Great Britain.

- 208 to 211 AD: Landing of Severus in Britain and subsequent costly campaign against the Picts and Caledons. In 211 the emperor dies in Eburacum (York). After his successor Caracalla made peace with the northern tribes, the situation in Britain seems to have largely calmed down again.

- 260 to 269 AD: Britain is part of the Gallic Empire under the usurper Postumus.

- 287 to 296 AD Usurpation and establishment of a short-lived Gaulish-British special empire by Carausius and Allectus.

- 296 to 305 AD: renewed consolidation of Roman rule and battles with the northern British tribes by the Caesar of the West Constantius I. He dies in Eburacum in 305 , the army then proclaims his son Constantine as his successor in the West.

- Late 3rd century AD: Establishment of the Litus Saxonicum (Saxon coast) in SE Britain.

4th century AD:

- 314 AD: Constantine adopts the title " Britannicus Maximus ", indicating a victory in a major war with the northern British tribes.

- 360 AD: Defensive battles against Picts and Scots.

- 367 AD: Common invasion of the British provinces by the Picts, Scots and Atticots. A large part of the Roman reconnaissance units made common cause with the barbarians. One of the commanders of the provincial army is also killed during the fighting. Stabilization of the situation by the Comes Flavius Theodosius.

- 382 AD: Restoration of Roman rule under Magnus Maximus. Maximus allows himself to be called to be emperor and withdraws large parts of his army from Britain in order to enforce his claim to rule.

5th century AD:

- Early 5th century AD: The north and the Litus Saxonicum are listed in the Notitia Dignitatum as separate military districts, commanded by a Comes Litoris Saxonici and a Dux Britanniarium . The commander of the field army is the most senior military in the British provinces, the Comes Britanniarum .

- 402 to 410 AD: End of Roman rule over Britain after the complete withdrawal of the field army under the usurper Constantine III.

literature

- Margot Klee : Limits of the Empire. Life on the Roman Limes. Konrad Theiss Verlag, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 3-8062-2015-8 .

- Thomas Fischer : The army of the Caesars. Archeology and history. With contributions by Ronald Bockius , Dietrich Boschung and Thomas Schmidts . Verlag Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg 2012, ISBN 978-3-7917-2413-3 .

- Kai Brodersen : The Roman Britain. Traces of its history. Primus, Darmstadt 1998, ISBN 3-89678-080-8 .

- Stephen Johnson: The Roman Forts of the Saxon Shore. 2nd Edition. Elek, London 1979, ISBN 0-236-40165-3 .

- Stephen Johnson: Late Roman fortifications . Batsford, London 1983, ISBN 0-7134-3476-7 .

- Alexander Gaheis: Iulius 49 . In: Paulys Realencyclopadie der classischen Antiquity Science (RE). Volume X, 1, Stuttgart 1918.

- Ronald Syme : Tacitus . Vol. 1 (of 2). Oxford 1958.

- Malcolm Todd : Julius Agricola, Gnaeus . In: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (ODNB). Vol. 30 (2004).

- Wolfgang Kuhoff : Diocletian and the epoch of the tetrarchy. The Roman Empire between crisis management and rebuilding (284–313 AD) , Frankfurt am Main 2001.

- Oliver Schmitt: Constantin the Great , Stuttgart et al. 2007.

- Matthias Springer : The Saxons . Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-17-016588-7 .

- Alex Woolfe: Romancing the Celts: Segmentary societies and the geography of Romanization in the north-west provinces , in: Ray Laurence and Joanne Berry (eds.): Cultural Identity in the Roman Empire. Routledge, Oxford 1998, ISBN 0-203-02266-1 .

- Geoff and Fran Doel, Terry Lloyd: King Arthur and His World. A journey through history, mythology and literature . Translated from the English by Christof Köhler. 2nd Edition. Sutton Verlag 2000, ISBN 3-89702-191-9 .

- Richard Hobbs, Ralph Jackson: Das Römische Britannien , Theiss 2011, ISBN 978-3-8062-2525-9 .

- Peter Salway: History of Roman Britain , Oxford History of England, Oxford Paperbacks 2001.

- Simon Mc Dowall, Gerry Embleton: Late Roman Infantryman, 236-565 AD. Weapons - Armor - Tactics . Osprey Military, Oxford 1994, ISBN 1-85532-419-9 (Warrior Series 9).

- John Morris: The Age of Arthur , Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London 1973, ISBN 0-297-17601-3 .

- Alfred Michael Hirt: Imperial Mines and Quarries in the Roman World: Organizational Aspects 27 BC-AD 235 (Oxford Classical Monographs), Oxford University Press, Oxford 2010, ISBN 978-0-19-957287-8 .

- Anthony R. Birley : The Roman government of Britain , Oxford University Press, 2005, ISBN 978-0-19-925237-4 .

- Anthony R. Birley: The people of Roman Britain , University of California Press, 1980, ISBN 978-0-520-04119-6 .

- National Museums & Galleries of Wales (Ed.): Birthday of the eagle: the second Augustan legion and the Roman military machine , 2002, ISBN 0-7200-0514-0 .

- Alan K. Bowman, Peter Garnsey, Dominic Rathbone (Eds.): The Cambridge Ancient History. Vol. 11: The High Empire, AD 70-192. University Press, Cambridge 2000, ISBN 0-521-26335-2 .

- A. Simon Esmonde-Cleary: The Ending of Roman Britain , Routledge, 1991, ISBN 978-0-415-23898-4 .

- Claude Lepelley (Ed.): Rome and the Empire in the High Imperial Era, Vol. 2: The Regions of the Empire, de Gruyter, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-598-77449-4 .

- Sheppard Sunderland Frere: Britannia: a history of Roman Britain , Routledge, 1987, ISBN 978-0-7102-1215-3 .

- Lawrence JF Keppie: Legions and veterans: Roman army papers 1971-2000 ( Mavors. Roman Army Researches Volume 12), Steiner, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 978-3-515-07744-6 .

- John Stewart Wacher: Coming of Rome (Britain Before the Conquest) , Routledge, 1979, ISBN 978-0-7100-0312-6 .

- Victor Erle Nash-Williams, The Roman frontier in Wales , University of Wales Press, 2nd edition, Cardiff, 1969.

- Stuart Laycock: Warlords. The Struggle for Power in Post-Roman Britain . Stroud 2009.

- Jann Le Bohec: The Roman Army. Nikol 2009, ISBN 978-3-86820-022-5 .

- Jörg Scheuerbrandt: Exercitus. Tasks, organization and command structure of Roman armies during the imperial era. Inaugural dissertation to obtain a doctorate from the Philosophical Faculty of the Albert Ludwig University in Freiburg / Breisgau, 2003/2004.

Remarks

- ↑ Doel / Lloyd 2000, p. 19

- ↑ C. Svetoni Tranqvilli. De vita Caesarvm libros VIII VI, 43 to 49.

- ↑ Patrick Reinard: Why didn't the Romans conquer Ireland? Communication from the Philipps University of Marburg, September 2017.

- ↑ Stuart Laycock, 2009, H. Fehr / P. von Rummel 2011, p. 107.

- ↑ Peter Salway 2001, p. 281, Richard Hobbs / Ralf Jackson 2010, pp. 35–36, Matthias Springer 2004, p. 33, A. Simon Esmonde-Cleary 1991, pp. 45–46, Alex Woolfe 1998, p. 207; Nennius : Historia Brittonum 66 , Doel / Loyd 2000, pp. 10-14, 17-18 and 30, Margot Klee, 2006, p. 10., Le Bohec 2009, p. 189.

- ↑ Claude Lepelley 2001, p. 217, Sheppard Sunderland Frere 1987, p. 72. The name Colonia Victrix is not clearly passed down; See Lawrence JF Keppie 1971-2000 , Mavors. Roman Army Researches Vol. 12, p. 304, John Stewart Wacher 1979, p. 74.

- ↑ Margot Klee p. 20

- ↑ Tacitus, Agricola 22 f.

- ↑ Tacitus, Agricola 22f, Malcolm Todd, ODNB Vol. 30, p. 824; Alexander Gaheis, RE X, 1, col. 136.

- ↑ Thomas Fischer 2012, p. 302.

- ^ Margot Klee, 2006, p. 11

- ↑ See military diploma from January 7, 306, ( AE 1961, 240 ); Origo Constantini 2.4. Wolfgang Kuhoff 2001, p. 794, Oliver Schmitt 2007, p. 102-106, Thomas Fischer 2012, p. 302. Doel / Loyd 1998, p. 18.

- ↑ Doef / Loyd 2000, pp. 19 and 29

- ↑ Doel / Lloyd 2000, pp. 14 and 19.

- ↑ barbarica conspiratio, Ammianus Marcellinus 27, 8, 1-6

- ^ "Iustinianus p (rae) p (ositus) Vindicianus magister turr [e] m castrum fecit a so (lo)" (AE 1954, 15 = CIL 7, 268 ), Doel / Loyd 2000, p. 22.

- ↑ Thomas Fischer 2012, p. 303, Doel / Loyd 2000, pp. 26-27.

- ↑ Doel / Loyd 2000, p. 27.

- ↑ Mc Dowall / Embleton: 1994, p. 64, Doel / Loyd 2000, p. 27.

- ^ David J. Breeze: Demand and supply on the northern frontier. In: Roger Miket, C. Burgess (Ed.): Between and Beyond the Walls. Essays on the prehistory and history of North Britain in honor of George Jobey. Edinburgh University Press 1984, pp. 265-276 (here p. 267).

- ↑ Scheuerbrandt 2004, p. 83

- ^ Kai Brodersen 1998, p. 185, Cassius Dio 72, 9, 1-4.

- ↑ According to Jona Lendering, while Emil Ritterling regards Durocornovium ( Cirencester ) and Glevum ( Gloucester ) as the first camps. According to another opinion, the Legion was divided into "many smaller detachments".

- ↑ Anthony R. Birley 1980 pp. 61, 82-86 and 2005, p. 148, Alfred Michael Hirt 2010, p. 176, National Museums & Galleries of Wales 2002, p. 76, A. Simon Esmonde-Cleary 1991, p 45-46.

- ^ Anthony R. Birley 1980, p. 45, National Museums & Galleries of Wales 2002, pp. 70-72 and p. 95, Bowman / Garnsey / Rathbone 2000, pp. 562-563.

- ↑ Doel / Loyd 2000, pp. 12 and 15, cf. Shotter, Romans and Britons, p. 49; the limit without d. Cumbrian coast according to Breeze / Dobson 9050 men, cf. Breeze / Dobson, Hadrian's Wall, p. 54, RIB 2401,1-8; CIL XVI 43; CIL XVI 69.

- ↑ Vegetius: Epitoma 4, 37.

- ↑ Hobbs / Jackson 2010, pp. 46-47

- ↑ Margot Klee pp. 9-10

- ↑ Thomas Fischer 2012, p. 302

- ↑ Hobbs / Jackson 2010, p. 42, Thomas Fischer, 2012, pp. 300-301

- ↑ Margot Klee 2006, p. 10

- ↑ Kai Brodersen 1998, p. 83

- ↑ Stephen Johnson 1979, pp. 68–69 and 1983, pp. 211–213, Thomas Fischer 2012, p. 303, Doel / Loyd 2000, p. 19.

Web links

- Castles on ROMAN BRITAIN

- The Romans in Britain. Sites, Museums and Resources (AF)

- Roman camps and forts in Britain

- Roman Governors of Britannia