Luguvalium

| Carlisle Castle | |

|---|---|

| Alternative name |

a) Luguvalium , b) Luguvallo , c) Luguvalii , d) Luguvalium Carvetiorum |

| limes | Britain |

| section | Stanegate |

| Dating (occupancy) | Flavian, 1st - 4th century AD |

| Type |

a) cavalry and cohort fort, b) supply depot |

| unit |

a) Legio IX Hispana , b) Legio XX Valeria Victrix , c) Ala Sebosiana , d) Ala I Augusta Gallorum Proculeiana , e) Ala Petriana , f) Limitanei |

| size | 3.2 ha |

| Construction |

a) wood-earth, b) stone construction |

| State of preservation | Square system with rounded corners, not visible above ground. |

| place | Carlisle |

| Geographical location | 54 ° 53 '46 " N , 2 ° 56' 26.5" W |

| Previous | Old Church Castle (Brampton) (east) |

| Subsequently | Portus Trucculensis (west) |

| Upstream | Uxelodunum Castle (Hadrian's Wall) (northeast) |

Luguvalium (Carvetiorum) ( pronunciation : [ ˌluːɡuːvælɪəm ]) was a Roman fort, including associated civil town in the area of the city Carlisle , county of Cumbria , District City of Carlisle in England .

Luguvalium was established as a military camp and supply base. The Roman army built a multi-phase wood-earth fort there in the late 1st century AD, which was replaced by a stone warehouse in the late 2nd century. In addition to the forts, a larger civil settlement developed. After Hadrian's Wall was built in the middle of the 2nd century AD, another fort was built in nearby Stanwix to accommodate a 1,000-man cavalry unit, the largest on Hadrian's Wall. When the majority of the occupation soldiers from the north were relocated there, Luguvalium's military importance as a border fortress declined; instead, like Coriosopitum in the east, it became a logistics center at the western end of the Stanegate. The city also became the metropolis of the indigenous Carvetii in the 3rd century . Until late antiquity , due to its proximity to Stanegate and Hadrian's Wall , as well as to the Cumbrian coast, it remained a regional administrative and settlement focus. Its position as a "frontier town" and the peculiarities of the surrounding area gave it a special role as a bulwark to defend Roman Britannia and later the border between two new, emerging kingdoms, England and Scotland .

Surname

The ancient name of today's Carlisle, had Celtic roots and originally meant the "fortress of Lugus or Luguwalos", a given name that is dissolved as "the power or strength of Lugus". It is not known who this Luguvalos was, possibly he was a member of the local aristocracy in the Iron Age , another high-ranking member of the Carvetii tribe or a deity, i.e. of theonymous origin. The latter is most likely. The name was in Welsh continue to be used, where the element caer extended ( "attachment").

- Luguvalium Carvetiorum (also Luguvallo or Luguvallio ) is first listed in the Itinerarium Antonini of the 3rd century, the

- Luguvalii of the 4th century in the Notitia Dignitatum . The city also appears as in the cosmography of the geographer of Ravenna , in the 7th century

- Lagubalium between the entries for Voreda (Old Penrith, Cumbria) and Magnis (Carvoran, Northumberland).

- Civitas Carvetiorum could have been the alternative name of the civil settlement.

The early medieval

- Cair Ligualid was mentioned in the Chronicle of Nennius among the 28 cities of Britain and in the Book of Taliesin , in which it was mentioned as

- Caer Liwelyδ (Welsh Caer Liwelydd) is called. These are probably derived from the original British name and therefore do not come from the Latin.

The earliest mention of the place in an Old English source is

- Civitas Luel (approx. 1050 / Beda), later names read on

- Carleol (1106),

- Karlioli and

- Cærleoil .

location

Its favorable location in the Cumberland Plain has given this place great strategic importance since pre-Roman times. Carlisle is 8 km above the tidal line, at the confluence of three rivers, about 16 km from today's border with Scotland and about 13 km upstream of the Solway Firth . Hadrian's Wall at Stanwix was less than 1 km north of Carlisle. The Roman fort stood at the northern end of a cliff overlooking the confluence of the Caldew in the Eden (Ituna ) north of today's city center. This was part of a low hill made of red sandstone, which extends gently uphill over the valley of Eden to the south. The sandstone cliffs form the roughly triangular-shaped steep slope occupied by the medieval castle today. Geologically, this is an Ice Age glacier moraine that has pushed itself over the alluvial silt and clay deposits of Eden. The highest points of the terrain are two peaks, which are now occupied by the city castle and St. Mary's Cathedral . To the north and west it drops steeply to Eden and Calder; in the east the Petteril flows past the fort. A few miles further north, the inlet of the Solway Firth forms the natural border with the Scottish Lowlands. Luguvalium also stood at the western end of the Stanegate , which connected them to the trade and supply center in the east, Coriosopitum (Corbridge). This and another highway to the north crossed the Eden east of the fort . The intersection of two long-distance routes encouraged the rapid development of the initial military base into one of the largest cities in Northern Britain. In the 2nd century the region belonged to the province of Britannia inferior , from the 4th century to the province of Britannia secunda and from the late 4th century - presumably - to the province of Valentia .

Road connections existed

- heading west to Aballava (Burgh by Sands, Cumbria),

- heading south east to Barrockside and Brampton / Old Church . Another road to the south ran along the Petteril between Carlisle and Penrith, marked by today's A6. Several signal stations have been identified alongside this road, including the tower at Wrey Hall.

- north to Uxelodunum (Stanwix, Cumbria), over the Moose to the outpost fort Castra Exploratorum (Netherby) and possibly even further to Broomholm. Another road branched off from this after the Lyne had been crossed south of Netherby. It probably also crossed the Esk at Burnfoot and continued west to the Blatobulgium (Birrens) outpost , then further into the Dumfries area,

- heading southwest to Old Carlisle ( Maglona ) and

via the military road (heading west) to Grinsdale. A recently discovered Roman road running east from Kirkbride near the mouth of the Wampool ran towards Burgh-by-Sands and must have also led to Carlisle. This street is believed to be the extension of Stanegate to the west in the early 2nd century.

Research history

Roman remains at Carlisle are mentioned by Beda Venerabilis (7th century), William of Malmesbury (11th century), John Leland and William Camden (16th and 17th centuries). Despite this long tradition of preoccupation with the Roman Carlisle, additional information about the origin, type and extent of Roman settlement in the city has only come to light in recent years. The theory that the hill occupied by Carlisle Castle was the site of a Roman fortress had been held since the mid-nineteenth century. An analysis of ceramic shards from the city also indicated an early Flavian military presence. Collar urns from the Bronze Age were found in 1861 on the site of Garlands Hospital. During the excavation at The Lanes, east of Scotch Street, a paved road and plow tracks were observed that are believed to be of prehistoric origin and that show an agricultural activity at the time. Isolated finds, including barbed arrowheads, are also evidence of prehistoric activities within the Carlisle area. The first archaeological evidence of a Roman fort in the urban area comes from the year 1892. From the early 19th century, a large number of urns and inscription stones from the 5th century came to light.

During the redesign of the city center in the 20th and 21st centuries, parts of the civil town and the southern part of the fort were repeatedly uncovered. Golden Fleece's temporary marching camp was discovered in aerial photographs taken between 1945 and 1949. At Tullie House, in 1954 and 1955 (Dorothy Charlesworth), remains of the foundations of a turf brick and wooden structure that belonged to the Agricolan fortress were found. It was eventually recognized as the foundation of the north wall. Judging by the findings, the former military site was evacuated by the army at the beginning of the 2nd century - possibly due to the construction of the Stanwix fort - and initially left to civilians. In 1978 excavations of the Carlisle Archaeological Unit took place further north on Annetwell Street. The south gate of Fort II, which had already been discovered in 1973, came to light. The finds in Annetwell Street also include the remains of wooden writing boards, comparable to that of Vindolanda , a fragment of an unlabeled altar made of red sandstone, a relief fragment made of the same material, and two statue heads with wall crowns, interpreted as guardian spirits ( Genii) .

In the mid-1970s, the Carlisle City Council decided to redevelop the old town streets (the Lanes), a densely built-up area in the northeast corner of the historic city center. The earlier archaeological digs had confirmed traces of complex Roman and medieval layers of finds in this part of the city, most of which would be destroyed by the modern development. Between 1978 and 1982, therefore, further archaeological investigations and related Analyzes and publication of project results carried out (Carlisle City Council, Historic England, Manpower Services Commission, Marc Fitch Fund and Society of Antiquaries of London). To this day, this project represents one of the largest and most important urban and archaeological projects carried out in the north of England. The results of these investigations were published in 2000. The early Roman settlement of the northern streets could be proven by the construction of the military camp and some large wooden buildings, possibly mansiones . Also the expansion of civil settlement in this area in the middle of the late second century AD could be based on the appearance of a certain pattern of building plots. The good conservation of water-soaked organic materials was a prominent feature of the early Roman Straten, which provided a wealth of environmental information and many artifacts made of wood and leather. Further investigations in the west of the city revealed indications of an intensive use of the area by the Roman civil population, which lasted into the early Middle Ages. It is also likely that the Flavian settlement activity was limited to the western and higher part of today's city center. Excavations near the city castle have uncovered parts of the southern and western defenses of the fort. Limited excavations in Abbey Street and Castle Street uncovered the remains of the defensive walls of the stone fort, just south of the former wall. Over the years remains of the Roman civil city have been observed again and again, including rooms that can be heated with hypocausts , presumably bathing facilities. Cemetery fields were uncovered along the main roads in the east, south and west of the city area.

The Millennium Project of the city of Carlisle between 1998 and 2001 has also considerably expanded our understanding of the processes surrounding the development of the Roman fortress. The excavations (Carlisle Archeology Ltd. and University of Bradford) focused on the southern part of the fort area, including the presumed Praetentura and a small area of the Latera Praetorii . More than 100,000 individual finds were recovered. A total of five excavation zones were examined prior to the construction of the pedestrian bridge over Castle Way (Irish Gate), the Millennium Gallery and the underpass. It was the largest archaeological dig in Carlisle since the early 19th century.

A Roman burial ground full of “extraordinary” cremation urns from the late 1st and early 2nd centuries, which was divided into several burial grounds and later used as workshop grounds, was discovered by archaeologists in 2015 at Botchergate (William Street car park). A completely preserved copper needle, possibly of Roman origin, was found in Paternoster Row. Only the tip was slightly bent.

Nowadays only a few Roman remains can be seen in place. Many of the finds recovered from Carlisle are on display in the Tullie House Museum, which is a division of the city's public library and art gallery. The exhibits include finds from everyday life in Roman Britain, such as B. Tools, ornaments, shoes, glass and pottery. It has the largest collection of finds at the western end of Hadrian's Wall and complements the collection in the Newcastle Museum in the eastern half of the Wallzone.

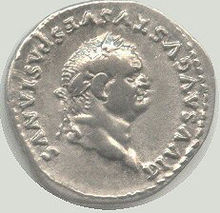

Inscriptions

Twenty-four Roman inscriptions have so far been recovered in Carlisle. There are fourteen altars and votive stones, nine gravestones and funeral inscriptions as well as an altar text, found in 1899, which consists only of the three letters LEC (Legion). The preferred deity for a military base is naturally the god of war Mars, to whom three altars have been dedicated, but all of which are shared with other deities. There are also two dedications to the genii (guardian spirits) and two altar stones to unknown deities. Two dedicatory inscriptions are dedicated to the Celtic-Roman deities Mars Barrex and Mars Ocelus (dated 227–235). William of Malmesbury claims to have seen a dedicatory inscription for Mars Victor in the 11th century on a "vaulted building". Maybe the ruins of a Roman temple. In addition, inscriptions were found that indicate one of Mithras ' companions , Cautes (and suggest a Mithraeum for Luguvalium ), Hercules (dated: 180–192 AD), the matrons (base inscription), the god of commerce Mercury , the goddesses of fate (altar) and another altar stone, which was dedicated to the Roman pantheon of gods (dated 213–222). A Roman milestone (dated 286-307) was discovered on Penrith Road at Harraby Bridge / Gallows Hill, south of Carlisle. Three inscriptions had been carved on it at different times; The original text had been smoothed out to make way for a dedication in honor of the British usurper Carausius . The stone was turned over and re-inscribed after his assassination and the reconquest of the island by the Caesar of the West, this time in honor of Constantius Chlorus .

Writing boards

During the excavations at Tullie House, Castle, Annetwell and Abbey Streets in the 1970s, 150 wooden writing boards (of the same design as those in Vindolanda ) from the late 1st and early 2nd centuries AD were found. to daylight. The letters were either written in ink or carved with a stylus . Such tablets were only found in Vindolanda and Carlisle. The texts of the copies written in ink contain a mixture of lists and letter sequences; only addresses could be read out on the stilus type. The majority of them were recovered from the layers of the wood and earth castles I and II. They are among the earliest Roman documents found in Britain. Most of the panels were recovered from landfills and debris from destroyed buildings. Their highly fragmented condition also suggests that they were exposed to the weather for a long time and were significantly damaged in the process. The texts presumably mainly deal with the daily operations of the unit stationed in the fort. Most of them are too poorly preserved to be deciphered. The best-preserved text clearly relates to purely military matters. It is not surprising that these tablets are mainly used in military camps and cities such as Londinium , as literacy rates are expected to increase in such places. However, their widespread use also proves the use of writing in rural areas, more extensively than previously suspected in research.

development

The heights of Carlisle are surrounded by the fertile Solway Planes, an area that has always been densely populated and is characterized by a relatively large number of prehistoric settlements. Many of them apparently come from the Iron Age , whose inhabitants cultivated the fertile soils. But there are also indications of even earlier settlement activities ( Bronze Age ). During excavations in Annetwell Street, the remains of a rural Iron Age settlement (round huts) have been observed. The hill on which the old town of Carlisle stands was probably also fortified at this time, although there is no archaeological evidence of this. The land around Carlisle belonged to the settlement area of the Celto-British Carvetii . Before the arrival of the Romans, Clifton Dykes appears to have been the chief town of this tribe, who lived mainly in Cumbria and north Lancashire . What is known about the early Roman history of Carlisle is derived mainly from archaeological finds and the writings of the Roman historian Cornelius Tacitus . According to Boethius and John Fordun , Luguvalion was one of the most powerful Celto-British cities before the arrival of the Romans. However , it is said to have been burned down during the reign of Nero .

1st century AD

The Romans advanced in the late 1st century AD to what is now the border area between England and Scotland. At the time of their rule over Britain, most of their occupation forces were concentrated here. The securing of the border through a dense chain of forts, such as Vindolanda, and through military roads such as the Stanegate , which connected them with one another, began in the late 1st century after the Romans had given up part of their conquests in Scotland. After the outbreak of hostilities with the north British tribe of the Briganten under Venutius , Emperor Vespasian decided to occupy their territory as well. He had already served as a legionary legate in Britain during the Claudian invasion (43). The governor at the time, Quintus Petillius Cerialis , was therefore commissioned with a punitive expedition in AD 71. The Legio IX Hispana from Lincoln and the Legio XX Valeria Victrix from Wroxeter invaded the tribal area of the brigands. Both legions were supported by auxiliaries. Cerealis commanded the Legio IX , marched with it up the east coast, first to Eburacum ( York ) and then on to Uxelodunum (Stanwix), at that time an important brigant oppidum , while the Legio XX marched along the west coast to Luguvalion to get hold of the brigands to take. With a convenient location on the Eden it was for shallow-draft ships of the Classis Britannica , attainable, so that the land forces rapidly and could be sufficiently supplied. Presumably the residence of Venutius was also there. After bloody fighting, the brigands were defeated in 73 AD and the Romans built their first wooden and earth fort in the late 1st century AD on the site of what would later become Carlisle Castle . Luguvalium was only used as a military base for a short time. To support the campaigns of Gnaeus Iulius Agricola in Caledonia, it was reoccupied by Legio XX around 78 AD . The continuing unrest led to the fact that the territory of the 79 Brigands was annexed by Rome. The occupation of Luguvalium was also supposed to secure the strategically important crossing at Eden. It was long believed to have served as the Legio XX base for their operations in south-west Scotland during the Agricola campaign , but it is believed that it served as one of the rallying points for returning troops during the Retreat from the Lowlands, 87 served.

2nd to 3rd century AD

In 122, Emperor Hadrian built the border wall named after him. The wall ran north of Carlisle through Stanwix (now a suburb of Carlisle). The camp in Carlisle, like some other forts on Stanegate, was not abandoned after the completion of Hadrian's Wall, but was now a military base of the rear line. After the demolition of the wood and earth fort I in the early 2nd century, a second wood and earth fort - with the same dimensions and floor plan - was built on the same site, possibly as a result of the reoccupation of southern Scotland under Emperor Antoninus Pius . The garrison is likely to have been reduced further and further until the Holz-Erde-Kastell II (still during the Antonine period) was destroyed and abandoned. Britain, like most provinces, was usually administered from the civitates under the provincial administration of the governor . There were also the border regions that were administered and monitored by the military. A text passage on one of the Vindolanda tablets shows that an Annus Equester around 103 was also stationed in Luguvalium . Another proof that the Stanegate extended at least to that point. In the late 2nd century the wood and earth fort was replaced by a stone fort, presumably built by the Legio XX . At the time of Septimius Severus (193-211), the civil settlement could have been granted second-order city rights ( municipium ). Under his rule the northern border region was comprehensively and reorganized. In 1993 a milestone was found in Brougham Castle ( Brocavum ) , on which the Civitas Carvetiorum is indicated. It comes from the reign of one of his successors, Alexander Severus , according to the title it was set up between the years 222-223. Accordingly, Luguvalium must have been elevated to the status of a city some time before. During the reign of Diocletian , around AD 296, the two provinces of Britain were divided again. The military administration of the newly established Britannia Inferior was entrusted to a legatus based in Eburacum , which meant that he was also in command of the only legion in the north. The civil administration, on the other hand , was the responsibility of a procurator , who could also dispose of contingents of auxiliary troops and probably resided in Luguvalium .

4th to 5th century AD

In the 4th century Luguvalium probably also advanced to the provincial capital of Valentia . The stone fort was in use by the regular army at least until the last third of the 4th century. According to Notitia Dignitatum, the military occupation of the city lasted until the late 4th or early 5th century. Late Roman coins found in Carlisle suggest that coins were in use there until the reign of Valentinian II (375 to 392). Likewise, the Romano-British settlement did not tear down immediately after the withdrawal of the Roman administration and field army around 410. However, the archaeological evidence suggests that the civil city began to decline as early as the fourth century. In the second half of the fifth century, the commanders of the Limitanei and militias in Northern Great Britain became local warlords, but formally recognized the superiority of Coelius (Coel Hen), probably the last official Dux Britanniarum to reside in Eburacum (York). The military district of the northern border split off from the rest of Britain as the autonomous kingdom of Ebrauc . The former Limitanei officers - or their descendants - soon founded their own dynasties. Ebrauc was divided into independent small kingdoms such as Bernica, Caer Guendoleu, Dunoting, Elmet , Rheged and the Pennines . The castle of Luguvalium could possibly have been used as an oppidum by the civilian population during this time, the so-called " Dark Age " .

Post Roman time

The fate of the city immediately after the dissolution of the Western Roman state (475-480) is largely uncertain. The infrastructure was falling into disrepair and its stone buildings were being demolished for the extraction of building material, a process that probably began as early as the 4th century and would continue into the 10th century. The early medieval Caer-Ligualid is likely to have retained its position as a regional administrative and trading center in the "dark ages". It will u. a. associated with the 6th century King Urien mentioned in the Historia Brittonum . Both the archeology and the related historical sources point to the existence of a town-like settlement at this time.

Carlisle was viewed in earlier research as the residence of the Celto-British kingdom of Rheged . But new excavations at Trusty's Hill Fort (Gatehouse of Fleet) now indicate that its center was probably there. Rheged finally came under Northumbrian rule after Rieinmellt , a daughter of Rhoedd ap Rhuns , had married Oswiu , the king of Northumbria , probably before 638 . In 685 Bishop Cuthbert von Lindisfarne stayed in Lugubalium to visit the Queen of Northumbrias in her sister's monastery. The chronicler Beda Venerabilis also mentions a royal court in this context, the high stone walls ( "..illis murum civitatis .." ) - presumably the city and not the fort wall - an impressive fountain, which was probably fed by the still functional Roman aqueduct and an administrator. In the same year, the surrounding land and its people within a 15 mile radius were awarded the Ecclesiastical Property of Cuthbert. His visit implies that towards the end of the 7th century there was still a community protected by a strong wall with a functioning infrastructure and rudimentary administration based on the Roman model. The excavations have not yet supported this tradition of the Bede, but they have also not revealed any signs of a city in complete decline. However, these findings still leave a large gap in time between the early fifth century and Cuthbert's residence.

For the remainder of the first millennium, however, Caer-luel apparently remained an important frontier fortress and was a constant bone of contention between the British Kingdom of Strathclyde and the Anglish Northumbria. It is also known that it was the residence of a bishop , Eadred Lulisc , at the end of the 9th century , and that it should have survived the conquest of the Angles as well as the border disputes largely unscathed. Here, too, as in many other parts of the Western Roman Empire, which fell in the 5th century, the Church had created the prerequisites through which a superficially Romanized society was maintained for a while and finally transformed into an Anglo-Saxon or English cultural community. The city is even considered by some to be the original home of the Irish national saint, St. Patrick . Around 876 it was probably stormed and devastated by the so-called great army of the Danes , the last historically significant event before the beginning of Norman rule. The Northmen held Carleol until the 10th century, then the Anglo-Saxons recaptured it .

Duke William of Normandy occupied England in 1066. At the time of the Norman invasion, Carlisle was part of the county of Northumbria that was still in constant border disputes with Scotland. In the late 11th century, Dolfin , the youngest son of the Gospatric , Earl of Northumbria, a vassal of the Scottish King, controlled Carlisle. In 1092, according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle , King William II Rufus stormed Carlisle and drove Dolfin out of the city. He founded the first city castle, which was probably still a simple wooden structure, surrounded by a ring wall made of earth ( Motte ). To secure the city, a new earth wall was raised, which largely followed the line of the Roman city wall and was broken by three gates (East: Scotch Gate or Rickergate, West: Irish Gate or Caldew Gate, South: English or Botcher Gate). In 1122, Henry I had Carlisle Castle rebuilt in stone on the site of the former Roman camp . The reconstruction of the city wall in Stein followed from 1130.

Castles

The exact location of the Roman fort remained unclear until the excavations on Annetwell Street from 1973 to 1984. The excavations have shown that the multi-phase castle of Luguvalium , which stood between the city castle and Tullie House, was in use from the 1st to at least the end of the 4th century AD. It was much older than the Stanegate border and was integrated into it between 103 and 105. The defenses were renewed roughly every ten years, and - presumably - each time the occupying force was relieved and replaced by a different unit. The north-eastern sector of its area is now under the city castle. The foundations of Fort III, the southeast corner and sections of the eastern and southern fort walls are only completely preserved between the city castle and the A595 (Castle Way Road) but are not visible. They have recently been examined using the most modern techniques. This made it possible for the archaeologists to determine the different phases of construction of the fort, the size and floor plans of which were apparently all the same or at least similar. Excavations on Annetwell Street uncovered the remains of a wall of turf, earth and wood. During excavations on the Millennium Side, within the fort, something rounded off the picture of the internal arrangement of the buildings and the location of the main building. The actual dimensions of the fortresses can no longer be verified. The local topography suggests that they all covered an area of about 3 hectares.

So far, three construction phases have been verified:

Castle I.

The Flavian wood-earth fort had the typical, playing card-shaped floor plan (axis alignment from NW to SE). It was clearly pre-Agricolan, this could be proven beyond doubt by means of dendrochronological dating of the timber, its southern defenses were accordingly built during the years 72–73 AD - in autumn or winter - and later abandoned. Coin finds indicate that the fortress was reoccupied during the Agricola campaigns between 78 and 79 AD. The interior development consisted of multi-phase wooden buildings. The other dendrochronological results indicate that some were renovated or rebuilt between 83 and 84 AD - again in autumn or winter. It is likely that at this time the high command decided to establish itself permanently in Luguvalium and therefore used oak from more distant areas instead of the locally more readily available alder for the renovation of the fort . The remains of the camp headquarters ( principia ), the commandant's house ( prätorium ) and two barracks ( contubernium ) were found in the south of the fort. The interior was apparently changed several times during the usage phase of this warehouse. Fort I was demolished between 103 and 105 AD and its area was leveled.

Castle II

The defenses of the Trajan wood and earth fort had apparently been moved further south in the early second century. This could have been caused by an increase in the fenced area. Wooden structures were also observed further to the southeast, they were probably also used by the military. Under the rule of Hadrian , the previous garrison was replaced and the interior buildings were completely redesigned or renovated. The change in the occupation force is most likely due to the completion of the Uxelodunum (Stanwix) wall fort . However, it was not completely abandoned in the 120s, but continued to be used until the beginning of the Antonine period. The activities there at that time are difficult to trace, but it is likely that it was not solely occupied by the military. It was probably only demolished as a result of the reoccupation of southern Scotland in the 140s. The only more closely examined gate, the south gate, had two passageways, flanked by slightly protruding wooden towers that were set into a mound covered with lawn tiles. The soil around the gate was unusually damp, which is why it was still very well preserved when it was discovered. Silting up in the second half of the second century suggests that the fort was deserted at that time.

Castle III

The late Cantonese stone fort was built in the late second or early third century (165-200), almost exactly over the two original wood-earth fort and again with the same playing card layout. One of its interior buildings was erected sometime after 165 in the south-eastern area along with a camp road. Also wooden buildings could be proven again. These were later also replaced by stone buildings. In the third century the fort seems to have been enlarged again; During excavations in Abbey Street and Castle Street, traces of the fort wall, which stood still further south of the defenses of the wood and earth castles I and II, were observed. It could also be an annex. Use of the camp by the regular military is assured until around 330; its fate after that is uncertain. In the case of the barracks, traces of a series of roughly executed stone foundations for unknown purposes were observed, which date from the late 4th century. Finds of coins and ceramics showed that it was used well into the 5th century. The interior of the stone fort was covered with a thick layer of humus when it was discovered, an indication that no people had lived there for a long period of time.

garrison

Luguvalium was presumably occupied by regular Roman soldiers from the 1st to the late 4th century. During its existence it housed several vexillations that were drawn out by the Roman legions or auxiliary units permanently stationed in Britain. At times there were probably up to 1,500 soldiers there. The soldiers of Legio II, IX and XX are therefore likely to have been among the first occupation units of the fort - as part of their work as building vexillations. In particular, the conversion to a stone fort required specialized craftsmen, who were usually only to be found with the legions and not with the auxiliaries who were later to be found in the garrison here. Legionnaires were used to build most of the empire's fortresses and were withdrawn from there after their completion. However, it is likely that they were stationed in Luguvalium until the 4th century and were used there as supply logisticians.

The location will u. a. also mentioned in a text in the Vindolanda tablets. Claudius Karus asks Flavius Cerialis, the site commander in Vindolanda , for his support for the application of Brigonius: "I ask you to recommend him as Annius Equester for Luguvalium ...", d. H. the board of the military administration responsible for the region (also centurio regionarius ). This officer commanded a troop of Regionarii , merited soldiers who had been assigned from other units to perform the necessary surveillance and police tasks in the military districts ( regio ) assigned to them . This could mean that Brigonius was also responsible for the organization and administration of the western sector of the Stanegate border. Brigonius is a Celtic name, it is even likely that he was a member of the British resident here. An Annius Equester led u. a. Censuses by. When the Romans consolidated their rule over a newly conquered area, one of their first measures was to keep the number of indigenous people on tax registers. He should therefore be well informed about the local conditions.

The following units were stationed in the forts of Luguvalium or could have stayed there for a limited time:

| Time position | Troop name | description |

|---|---|---|

| 1st century AD |

Legio secunda Augusta ("the second legion of Augustus ") |

An altar from Carlisle was dedicated by the Legion to Concordia (Concord). Another dedication of this kind comes from Coriosopitum , in this case by members of the Sixth and Twentieth, of whom vexillations were stationed there in the 3rd century. This altar indicates that the Second and Twentieth Divisions were barracked together in Carlisle. |

| 1st century AD |

Legio nona Hispana ("the ninth legion of Hispanics ") |

About five miles south of Carlisle, in Scalesceugh, brick temples belonging to this legion were discovered in 1921. Presumably she stayed in Carlisle during the Flavian era and built the wood and earth fort I there. The Legio IX was withdrawn from Britain around 120 AD. |

| 2nd to 3rd century AD |

Legio Vicesimae Valeria Victrix Antoniniana ("the twentieth Valerian Legion, the strong and victorious, the Antoninian ") |

Presumably soldiers of this legion built the wood and earth fort II. The honorary title Antoniniana was bestowed on her under Emperor Caracalla (213-217 AD) or Elagabalus (218-222 AD). An altar from Carlisle (from 213 or 222) for the supreme Roman gods and goddesses was dedicated by the tribune to Marcus Aurelius Syrio, son of Marcus, from the city of Ulpia Nicopolis in the province of Thrace. Another - labeled - altar fragment could also have been commissioned by this legion. |

| 1st century AD |

Ala (Gallorum) Sebosiana ("the first Gallic cavalry squadron of Sebosius") |

In the earliest layers of the fort, a large number of wooden writing boards came to light in Vindolanda . The texts contained therein suggest that this cavalry troop could have been a garrison ( auxilia ) in Carlisle at the time of the Flavians . |

| 2nd century AD |

Ala prima Augusta Gallorum Proculeiana ("the first Augustan cavalry squadron of the Gauls of Proculeius") |

An inscription on a Hercules altar found in Carlisle and dated to the reign of Commodus (176–192 AD) refers to the successful defense of one

Barbarian attack by this cavalry unit. |

| 2nd century AD |

Ala Petriana ("the first cavalry squadron of Petra") |

Twenty years later there was another cavalry unit. After she had been increased to over 1000 soldiers ( Ala miliaria ), she was transferred to Stanwix or to Hadrian's Wall. A dedicatory inscription donated by Prefect Luca was found in Carlisle. |

| 4th to 5th century AD | Limitanei ("border guards") | According to the list of troops relevant to Hadrian's Wall in the Notitia Dignitatum , the Luguvallii of the late 4th century contained a unit of late Roman border troops that was not known by name and was under the command of the Dux Britanniarum . Since the troops still appear in this late antique document, they could have stood there until the final withdrawal of the Roman army. |

Civil city

The civil town of Luguvalium is mentioned for the first time on writing tablets that were recovered in Vindolanda in the 1980s . The isolated excavations in the old town have also clearly confirmed the existence of an extramural civil settlement, which perhaps existed since the Flavian period. In the course of Roman times, the settlement developed into a small town that stretched south and east of the fort. There is no doubt that Luguvalium flourished mainly due to the long-lasting presence of the Roman military, first on the south bank of the Eden and later also further north, where there is another smaller settlement in the area between the Uxelodunum (Stanwix) fort and the river developed. Otherwise there is very little evidence of settlement activity west of the Caldew. Unfortunately, although large in size, very little is known about the city and the types of buildings it contained. Like Coriosopitum in the east, Luguvalium began as a first century fortress and both continued to have a military base in the center. Despite their continued military importance, the civil element of these settlements had become increasingly important and economically prosperous by the late second century: enough to make Luguvalium civitas shortly thereafter . They were cities that were designed rather than naturally developed. The streets were arranged in a regular grid, they were u. a. equipped with a basilica, a forum, a public bath and running water. It is still a matter of dispute whether these institutions were always all built on the initiative of the Roman state.

administration

The city was probably elevated to the status of the metropolis of the Carvetii, the Civitas Carvetiorum , in the early 3rd century (under Septimius Severus) . This "Council of Carvetii" is first attested in writing during the reign of Alexander Severus (222-235) and it almost certainly met in the city. It is also likely that due to the numerous Roman veterans who lived here and are also documented by inscriptions, it was granted a town charter ( Municipium ). From an undated tombstone from Voreda (Old Penrith), a high administrative officer of the Civitas Carvetii is known, Flavius Martius, who had served as councilor ( senator ) and quaestor of the Carvetii and was 45 years old. In the course of time various changes took place in the functions and titles of the city and local government. For example, council members were more frequent in the later Empire as curiales called although the Decurio never fully fell into disuse. Occasionally a decurion is also referred to as a senator , as on the tombstone of Martius. The territory of the civitas probably comprised the northwestern part of the original tribal area of the brigands. The administration based on the Roman model apparently lasted until the 7th century, since in the Chronicle of the Bede Venerabilis a Praepositus civitatis is mentioned as head of the city.

population

How many people lived in Luguvalium Carvetiorum during its heyday is unknown. Only a rough estimate can be made here. The high points of the population development were certainly the founding phase and the campaigns of Agricola until 80 AD, the withdrawal of the army from Scotland and the consolidation of the Stanegate border from 139–140. Military personnel were withdrawn mainly between 122 and 160, after the completion of Hadrian's and Antonine walls. The last time there was probably a greater population growth during the Scottish campaigns of the Severians (208–211). In any case, the findings of archeology make it clear (among other things, inscriptions in Greek and Latin have been found) that the Roman city was one of the busiest and cosmopolitan places in Northern Great Britain during the period of its existence .

city wall

The layout of the Roman city resembled an elongated triangle that stretched slightly to the southeast, probably 28-30 hectares in size, and changed only insignificantly until the early modern period . The first fortification of the city seems to have consisted only of a palisade and a moat. They probably only served as an entry block to collect tariffs from travelers. It is not known when it was fortified with a stone wall. In those cities in which Roman or Anglo-Saxon defenses were still well preserved, these were repeatedly repaired and continued to be used. It is therefore assumed that the later - medieval - city wall of Carlisle still largely followed the line of the Roman wall. But it is also possible that the city was never completely defended (McCarthy).

Road system

The north-south main street ( cardo maximus ) started from the south gate of Fort I and reached at least as far as Blackfriars Street / Botchergate, at the northern end of which porticos accompanying the street could be identified. The putative east-west axis ( decumanus maximus ) of the Roman city is marked by Castle Street. A second street, starting from the forum and running from northwest to southeast, which is partly under what is now Scotch Street, led to Uxelodunum (Stanwix), where one could cross the Eden on a bridge.

Water supply

The impressive aqueduct and fountain, which Sankt Cuthbert claims to have seen in the 7th century, could not yet be archaeologically recorded. A stone water tank in the portico of a building uncovered at Tullie House could have been fed from it. The water source for this was probably on a plateau in the south of the city.

Interior development

The buildings were essentially lined up along the three main streets. Major excavation campaigns, particularly the excavations in The Lanes, provided important information about the development of the Roman city. First of all, large wooden buildings were erected on their area, which probably still served purely military purposes. The west side of the city area was initially only used by civilians, later it was evidently completely cleared by the army in the east and also left to civilians. The military buildings were leveled and new buildings were erected over them. Wooden buildings from before AD 150 stood in Keays Lane, including a kind of praetorium , which was obviously only in use for a short time. As in Fort III, the first stone buildings were erected in the late second to early third centuries.

There was probably a temple on Scotch Street. In Annetwell Street remains of wooden buildings of the 2nd century were found, which were also replaced by stone buildings under the Severians. They resembled barracks blocks and were separated from one another by streets. It is believed that they belonged to some kind of military enclave or arsenal, comparable to the legionary quarters in Corbridge . In addition, finds came to light (brick stamps, inscriptions, architectural fragments) that can be traced back to the three legions that can be identified in Luguvalium . The city's political, legal, economic and religious center, the Forum , was likely located at what is now the Market Cross. Finds indicating a temple precinct were found on English Street. Inscriptions confirm that a mithraeum and possibly also a temple of the Celto-British god Belatucadros / Mars stood in the city . Other excavations have uncovered the location of a large late Roman bathhouse ( thermae ) under the Victorian market hall in the center of today's old town and some well-appointed houses with hypocausts in Keays Lane. It was rebuilt several times in the 3rd and 4th centuries. The previous building there resembles a market hall with one or more tholoi , as can be seen in the African Leptis Magna . This house coexisted with a - remarkably long-lived - half-timbered building in a lane leading to the north that existed until the end of the 4th century.

In the center of today's old town (at the intersection of Castle Street and Fisher Street), a single massive stone building - measuring 55 × 13 meters - with about 2 m thick walls from late antiquity has been examined in more detail. It was flanked to the west by a possible road that runs parallel to the main axis between northwest and south. This building, near what is believed to be the ancient city center, could have had a public function; it may have been used for administrative purposes. The discovery of 12.2 x 67 m, late Roman strip houses on Blackfriars Street confirms the continuity of the settlement well into the 5th century.

Post Roman time

As is so often the case, knowledge of the early medieval activities in former Roman cities is extremely limited. On Blackfriars Street, the late Roman strip houses were finally replaced by hall-like buildings, the characteristics of which are described in research as Anglo-Saxon. Though exact dating was impossible. There is also evidence that some elements of Roman infrastructure still existed in the 7th century, such as: B. the ancient water pipe system. In addition, Beda Venerabilis mentions a nunnery and possibly another abbey in his chronicle, which may have been associated with the early St. Cuthbert's Church. The church itself seems to have been aligned with the Roman road network (from east to west), and the relevant finds are also concentrated on the line of the former main street of the Roman city, which ran from northwest to southeast. This finding also includes coins that date to the 8th and 9th centuries.

economy

The prosperity of the civil town was probably based exclusively on the trade and the supply of the crews of Hadrian's Wall with everyday goods. If they ever really became important trading or administrative centers for the indigenous British of the surrounding area, then after 200 AD at the earliest, Villa rustica and other signs of the development of the country by a Romanized elite are still missing in their hinterland. Much of the economic activities of its residents were probably carried out on behalf of the army, who worked for them in one capacity or another. In Botchergate and Rickergate standing (multi-phase) timber and half-timbered buildings, border moats of the parcels, individual burials and references to craft activities were uncovered directly on the street front. Buildings and finds could be dated to the period between the early third to fourth centuries AD. Local economic activities included u. a. copper and leather processing. Luguvalium is also the only place in Roman Britain in which a training center for stonemasons could be proven. These created u. a. Local sandstone tombstones, some of which have been found in surrounding Romano-British settlements such as Old Carlisle and Bowness. It was in operation from the Antonine period until the 3rd century. About 150 yards east of the fort, on Fisher Street, was a major pottery from the late first or early second century. In the middle of the 2nd century, two circular workshop buildings were built on the Botchergate burial ground, which were used either for metal and glass processing or for dyeing textiles. The latest excavations in the north of the ancient city area revealed evidence of iron and lead processing. Luguvalium, as a typical border town, earned a large part of its prosperity not only through the production of goods for the garrison soldiers of the wall, but also through long-distance trade across the empire via the well-developed road network. Trade relations existed not only with the neighboring Coria (Corbridge), but also with Viroconium (Wroxeter) in Wales and certainly also with cities in provinces on the continent such as B. Carnuntum , where the Amber Road coming from the Baltic Sea crossed the Danube and reached as far as northern Italy. Excavations in Old Grapes Lane revealed remains of coriander, sloe , plums, cherries, apples / pears, walnuts, olives, grapes and lentils in human food residues . The existence of these fruits, which were exotic for the region at the time, proves the extensive trade relations and thus also guaranteed the availability of such luxury goods in the remote bases of the Roman north of Great Britain. Merchants could be proven epigraphically in Luguvalium . A Greek trader, Flavius Antigonus Papias, probably an army supplier, was here in the early 2nd century AD. buried

Burial ground

Numerous Roman burials have also been discovered in Carlisle. Since it was strictly forbidden to bury the deceased within the city walls, the graves were laid on the roadsides. In Carlisle they were laid out along the main arterial roads. In this way, the course of these streets in the Roman Luguvalium could be determined. Two burial grounds were believed to have been along the main road (Castle Road), which ran east to west. The largest stretched along both sides of what is now London Road from the South Gate along Bothchergate, William Street to Gallows Hill. This burial ground probably marks the course of the trunk road that led in the south-west to Old Carlisle, Papcastle and from there on to the Cumbrian coast. Individual graves were still found on Murrell Hill and in Botcherby. A total of 30 cremation burials ( ustrina ) and skeletal graves were uncovered. The finds included a. a stone lion, a column in the shape of a pine cone wound around by a snake, a few smaller sculpture fragments, wooden or lead coffins, stone sarcophagi and graves lined with stone slabs or bricks. The ashes from cremations were buried in urns made of clay, lead and glass. Most of these finds are now on display at the Tullie House Museum. The names of some of the inhabitants of the ancient city are also known from grave inscriptions. Including the Greek Flavius Antigonus Papias, who died at the age of 66 and was presumably a Christian when he died, a man named Malrius Martialis, Anica Lucilla who lived for 55 years, Aurelia Senecita who lived for 20 years, an unknown soldier and a likewise unknown deceased at 35 Years old. Another tombstone was placed for Aurelia Aureliana (died at the age of 41) by Ulpius Apolinaris. The female figure on the tombstone of Vacia, who died at the age of three, wears a long tunic with a belt and a cloak. She is presumably holding grapes in her right hand. It was still lying on her oak coffin and dates from the middle of the third century. The stone was probably bought ready-made, as the relief shows a person who is clearly older than the toddler named in the text. It was found on Bowling Green, on the east side of the north end of Lowther Street (now in the Tullie House Museum). An unlabeled headstone from Murrell Hill is a fine example of Provencal Roman art of the time. It shows a mother, dressed in a long tunic, sitting in a chair with an open fan held in her right hand. Next to her is a child who is petting a bird on his lap. Christianity is represented by a tombstone and a gold ring with an incised palm branch and the words AMA ME, but this religion was probably more important for the post-Roman Carlisle.

March camps and signal stations

Several temporary marching camps and watchtowers were found in the vicinity of Carlisle.

| Ground monument | description |

|---|---|

| Nowtler Hill I. | The existence of two Roman fortifications, 300 m apart on Nowtler Hill, just over 1 km southwest of Grinsdale, has been known for nearly two centuries. Site plans of them were first made around 1800 by Daniel Lysons. The fortifications were also mentioned by John Hodgson in 1840. In the early 1850s, what was still visible was destroyed by plows. By 1938 they had completely disappeared. They could be rediscovered from the air between 1945 and 1949.

The marching camp was located on the highest point of Nowtler Hill, an approximately 35 m high, rounded elevation that is part of a terrain spur that protrudes to the northeast and overlooks the Valley of Eden. This position provides a good view of all heavenly directions, especially over the hinterland of Hadrian's Wall. The earth wall of this relatively small camp enclosed an area of approx. 0.5 ha. The floor plan is not exactly rectangular, the northwest and southeast sides measure 78 m and 73 m respectively and the northeast and southwest side 64 m. The west and east corners are rounded, the north and south corners are slightly tapered. The titulumatore are located on the north-west, south-east and north-east side, the first two being secured by ramparts (clavicula). Although the wall on the northeast side is no longer visible in aerial photos due to its proximity to the modern motor road, its existence is confirmed by both Lysons and MacLauchlan. Lyson's records, however, do not match the older reports as his description indicates a titulum gate on the SW side. Probably a mistake, as the surrounding moat can be clearly seen as continuous on aerial photos. However, it is possible that this was due to the creation of a drainage trench. |

| Nowtler Hill II | Camp II is located about 300 m southwest of camp I, on a very gently rising, south-westerly, 35 m high slope, immediately southwest of Nowtler Hill. A wide, low saddle connects it with the area of Camp I. Its position offers a far-reaching view in all directions, except to the northeast. The rising terrain of the hill restricts the view over camp I here. The fortifications, which were very small in terms of area, had a rectangular floor plan oriented east-south-east to west-north-west. The fenced-in area measures about 57 × 39 m and covers an area of about 0.2 hectares. According to Daniel Lysons, the circumferential moat was interrupted on all four sides by access roads to the claviculators, each of which was secured by a wall ( tutuli ). This is confirmed by aerial photographs on three sides, but evidence of an earth dam on the east-south-east side was destroyed by the planting of a modern hedge that cuts right through its center. |

| Golden fleece | This camp is located 300 m east of the hamlet of Golden Fleece and 5 km southeast of Carlisle, on an approximately 70 m high plateau. It stood on the gently sloping northwest slope of a wide ridge that stretches from northeast to southwest. From there you overlook a narrow watercourse that flows into the Petteril, as well as the north and northwest of the river valley. The Roman road from Carlisle to Old Penrith ( Voreda ), which runs about 450 m southwest of the site, is also still in sight. The camp was aligned to the SSE and covered an area of 0.5 hectares. Its sides are not exactly parallel to one another, although there does not seem to be any topographical reason for this. The west corner is right-angled, but the southern ditch is slightly shorter than on the north side. The south wall was 2.5 m higher than the one on the north side, it ran directly on the ridge of the terrain. There are still four Titulum gates to be seen, three of which were secured by earth walls ( clavicula ) about 8 m in front . The west gate can only be seen very faintly. The storage area is disturbed by herringbone-like drainage ditches which can also be seen on aerial photos. |

| Barrockside | The camp was on the eastern side of the Petteril Valley, about 520 m southeast of Barrockside Farm and a little over 1 km northwest of Low Hesket. The Roman Road from Old Penrith to Carlisle runs about 600 meters east of here. The camp, which is oriented from north to south, is located on an 80 m high ridge that slopes gently to the NE. A small stream, most of which is now piped, runs a short distance along the east side of the camp and then turns to the northwest immediately north of the camp, finally flowing into the Petteril. From the camp you can see far to the northwest, west and south along the Petteril. The view to the north, northeast and south are restricted by mountain ridges. In the south, a 300 m high ridge blocks the view. The camp's ground plan is irregular and south-facing. It was surrounded by a moat. There is no apparent topographical reason for the somewhat asymmetrical shape of the square camp, which covers an area of approximately 0.8 hectares. The north side measures 72 m, the east and west sides between 102 and 103 m. The south side is 5 m shorter than the north side, which runs almost parallel to it. This inclines slightly inward in its course. The east and west sides, both about 107 m long, are also not quite parallel to each other. The NW and SE corners are rounded, but the NE and SW corners are slightly pointed. The west ditch is approx. 30 m away from the slope on the valley side. All four sides seem to have been broken through by a gate. A trench crossing can only be seen at the south gate. |

| Plumpton Head | The camp can only be recognized today by means of elevations in the ground. The existence of a camp in this hilly area, immediately northwest of the hamlet of the same name, has been known for a long time. However, it was not until the 1970s that the RCHME was able to determine its complete floor plan with detailed field investigations and aerial photographs. It lies in the valley of the Petteril, on a plateau between 130 m and 137 m high, 60 m west of the Roman road from Eburacum (York) to Luguvalium and only 3.1 km south of the Voreda fort (Old Penrith). This position offers a good view in all directions, especially to the west, which however cannot be seen from the adjacent section of the Roman road. The defensive walls of the camp enclose its area in the form of an irregular polygon. The camp covers a broad valley depression that extends from north to south. It enclosed an area of about 9.5 hectares. Its west side, about 350 m long, runs parallel to a ridge that extends northwest from the edge of the Petteril floodplain to a point near the river bank. This marks the northwest corner of the Marschlagers. The northern side of the camp, which is mostly flat except for its western end, is the most irregular of all. Its eastern section is in two separate sections, and its central section curves unusually abruptly about 35 m to the south. These distractions should probably avoid the very swampy ground there. The defensive moat, which is still clearly visible on the east side of the camp, which is around 170 m long, is interrupted by three relatively closely spaced, unusually wide titulum gates, each of which is protected by a wall ( clavicula ) in front of it , which is around 18 m apart from the warehouse wall. The south wall of the camp is only faintly visible, it was about 330 m long, including a slight deviation about 50 m east of the southwest corner. The fact that the camp is not aligned with the Roman road could indicate that it was built before the road was built. |

| Wrey Hall | Elevations indicating a Roman watchtower were discovered in an aerial photograph from 1946 and excavated by Richard Bellhouse on March 17, 1951. The tower was west of the sixth milestone on the Carlisle to Penrith road, near Wreay Hall. The findings revealed a square trench with rounded corners, separated from an outer circular trench by a wide strip of land (with the remains of a heaped mound). Based on the pottery found there, Ian Richmond identified the tower site as a signaling station from the 4th century. In 1958 a small temporary marching camp was observed under the layers of the signal station. Its entire NW and SW sides and a section of the NE side could be traced. |

literature

- Beda Venerabilis : Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum , Online in the Medieval Sourcebook (English)

- Anonymous: Anglo-Saxon Chronicle , online in Project Gutenberg (English)

- Theodor Mommsen: Nennius, Historia Brittonum, VI. Composed after AD 830. (Latin version).

- W. Whellan: The History and Topography of the Counties of Cumberland and Westmorland, Pontefract 1860.

- M. Creighton: Historic Towns: Carlisle. London 1889.

- John of Fordun: Chronicle of the Scottish Nation, Edinburgh, Edmonston and Douglas. In: The Historians of Scotland, vol. IV. 1872.

- RS Ferguson: On a massive timber platform of early date uncovered at Carlisle: and on sundry relics found in connection therewith, Trans Cumberland Westmorland Antiq. Archaeol. Soc., 1 ser., No. 12, 1893, pp. 344-364.

- HA Doubleday: Victoria History of the County of Cumberland, 3 vols, London 1901.

- Nicholas Higham, Barri Jones: The Carvetii. Sutton, London, 1985.

- JP Huntley: Plant remains from excavations at The Lanes, Carlisle, Cumbria: Part 1 — CAL, OGL, OBL, and LEL. Ancient Monuments Laboratory Report 51, 1992.

- ID Caruana: Carlisle: Excavation of a section of the Annexe ditch ot first Flavian fort. Britannia 22, 1990.

- Rachel Newman: Carlisle: Excavations at Rickergate, 1998-1999 and 1953-1955 Botchergate, 2001, Cumbria Archaeological Research Reports, Paperback, 2011.

- David Shotter: Romans and Britains in North West England. Lancaster 1993.

- RH Bewley: Prehistoric and Romano-British Settlement in the Solway Plain, Cumbria, Oxbow monog. 36, Oxford 1994.

- B. Colgrave: Two lives of St. Cuthbert, Oxford 1940.

- Ronald Embleton, Frank Graham: Hadrian's Wall in the Days of the Romans. Newcastle, 1984, pp. 311-316.

- RG Collingwood, RP Wright: The Roman Inscriptions of Britain. Oxford 1965.

- AR Burn: The Romans in Britain An anthology of Inscriptions. Oxford 1932.

- Malcolm Todd: The Small Towns of Roman Britain. Britannia 1, 1970, pp. 114-130.

- Peter Salway: The Frontier People of Roman Britain. Cambridge University Press, 1965.

- Allistair Moffet: The Borders: A History of the Borders from Earliest Times, Birlinn, 2011.

- Barry Burnham, John Wacher: The Small Towns of Roman Britain. University of California Press, 1990.

- John Watcher: The Towns of Roman Britain. 2nd Edition, Routledge, London / New York 1995.

- Albert Rivet, Colin Smith: The place-names of Roman Britain. 1979.

- Eilert Ekwall: The Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Place-names. Clarendon Press. Oxford. 1936-1980.

- KM Sheard: Llewellyn's Complete Book of Names for Pagans, Wiccans, Witches, Druids, Heathens, Mages, Shamans & Independent Thinkers of All Sorts who are Curious about Names from Every Place and Every Time. Llewellyn Worldwide, 2011.

- M. Lewis: Temples in Roman Britain, 1966.

- Kenneth Jackson: Language and History in Early Britain. Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh 1953. ISBN 1-85182-140-6 .

- H. Fulton: Why was Welsh Literature First Written Down? in: Medieval Celtic Literature and Society. Four Courts Press, Dublin 2005. ISBN 1-85182-928-8 . Pp. 15-31.

- Dorothy Charlesworth: Roman Carlisle. Royal Archaeological Institute. The Archaeological Journal, No. 135, 1978, pp. 115-137.

- W. Hanson, L. Keppie: Roman frontier studies 1979: papers presented to the 12th International Congress of Roman Frontier Studies, BAR international Series 71, 1980 pp. 201–211

- Mike McCarthy: Current archeology, 68, 1979, pp. 269-270

- Mike McCarthy, H. Summerson, R. Annis: Carlisle Castle: a survey and documentary history. English Heritage archaeological reports No. 1, 1985 - No. 24, 1994, No. 18, 1990, pp. 4-6

- Mike McCarthy: British Archaeological Report. British series 1 - Thomas Chadwick and Post-Roman Carlisle, 1974.

- Mike McCarthy: Roman Carlisle & the lands of the Solway. Tempus, 2002.

- Mike McCarthy: A Roman, Anglian and Medieval Site at Blackfriars Street. Stroud 1990.

- Mike McCarthy: Carlisle A Frontier and Border City, 1st Edition, Routledge 2017.

- Mike McCarthy: Carlisle: Function and Change between the First and Seventh Centuries AD, Archaeological Journal, No. 175: 2, 2018, pp. 292-314.

- Mike McCarthy: Roman and Medieval Carlisle: The Southern Lanes, Archeology Limited Res Rep, 1, Carlisle, Carlisle 2000.

- Mike McCarthy, M. Summerson: Carlisle Castle: a survey and documentary history. English Heritage Archaeol Rep, 18, London 1990.

- Mike McCarthy, T. Padley, M. Henig: Excavations and Finds from the Lanes, Carlisle. Britannia, Vol. 13, 1982, pp. 79-89.

- The Carlisle Millenium Project - Excavations in Carlisle 1998-2001, Vol 1: Stratigraphy, Oxford Archeology North, 2010.

- Pat Southern: Hadrian's Wall: Everyday Life on a Roman Frontier. Amberly Publishing, The Hill, Stroud, Glouchestershire 2016.

- Eric Birley: Research on Hadrian's Wall, 1961.

- JP Bushe-Fox: The use of samian pottery in the dating of the early Roman occupation of the north of Britain, Archaeologia, 64, 1913, pp. 295-314.

- Dorothy Charlesworth: The south gate of a Flavian fort at Carlisle, in: Hanson / Keppie: Roman frontier studies 1979, BAR Int. Ser. 71, Oxford 1980, pp. 201-210.

- John Pearce: Archeology, writing tablets and literacy in Roman Britain. In: Gallia 61, 2004.

- R. Hogg: Transactions of the Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian & Archaeological Society, No. 64, 1964, pp. 58-59

- R. Hogg: Transactions of the Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian & Archaeological Society, No. 55, 1956, p. 72

- R. Goodburn: Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies Britannia: a journal of Romano-British and kindred studies, No. 10, 1979, p. 281

- FO Grew: Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies Britannia: a journal of Romano-British and kindred studies, No. 11, 1980, pp. 359-360

- T. Podley: Council for British Archeology Group 3: Archaeological newsbulletin, No. 21, 1983, p. 9

- Mark Hassall, Roger Tomlin: Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies Britannia: a journal of Romano-British and kindred studies, No. 12, 1981, p. 379

- Coles / Orme: Trust for British Archeology and Council for British Archeology Rescue news: the newspaper of RESCUE, the British Archaeological Trust, No. 31, 1983, pp. 1 and 8

- P. Wilson, R. Jones, D. Evans: Settlement and society in the Roman north. 1984, pp. 65-70

- Anne Johnson: Roman forts of the 1st and 2nd centuries AD in Britain and the German provinces. 1983, p. 84

- Timothy Potter: 1979 Romans in north-west England: excavations at the Roman forts of Ravenglass, Watercrook and Bowness on Solway. Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society research series 1, Vol. 1, 1979.

- Timothy W. Potter, Catherine Johns: Roman Britain. University of California Press, 1992.

- John Kenneth St. Joseph: Society for Promotion of Roman Studies The journal of Roman studies. No. 41, 1951.

- Humphrey Welfare, Vivien Swan: Roman camps in England: the field archeology. 1995.

- Transactions of the Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian & Archaeological Society. No. 88, 1988, p. 87

- Transactions of the Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian & Archaeological Society. No. 94, 1994, p. 67

- Transactions of the Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian & Archaeological Society. No. 91, 1991, pp. 31-48

- B. Edwards, D. Shotter: Two Roman milestones from the Penrith area, Trans Cumberland Westmorland Antiq Archaeol Soc, 3 ser. 5, 2005, pp. 65-77.

- Nick Hodgson: Hadrian's Wall 1999-2009. Pp. 140-150

- P. Wilson, R. Jones, D. Evans: Settlement and society in the Roman north. 1984.

- Helmut Birkhan : Celts. Attempt at a complete representation of their culture. Publishing house of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna 1997, ISBN 3-7001-2609-3 .

- David Nash Ford: The 28 Cities of Britain. Britannia, 2000, Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies Britannia: a journal of Romano-British and kindred studies 25, 1994.

- R. Allen: English Castles. Batsford, London 1976.

- David Breeze: Roman Forts in Britain. Shire Archeology, Oxford 2002.

- R. Fleming: Britain After Rome. Penguin, London 2011.

- H. Summerson: Carlisle Castle. English Hermitage, London 2008.

- HL Turner: Town defenses in England and Wales. John Baker, London 1970.

- K. Branigan: Rome and the Brigantes: The Impact of Rome on Northern Britain. University of Sheffield Press, Sheffield 1980.

- North Pennines Archeology, 2004 Interim report for an Archaeological Excavation at the Maltsters' Arms, 17 John Street, Caldewgate, Carlisle, unpubl. rep.

- RC Shaw: Romano-British Carlisle: its structural remains, Trans Cumberland Westmorland Antiq. Archaeol. Soc., New series 24, 1924, pp. 95-109.

- Frank Gerald Simpson: The Wall at the sewage disposal works, Trans Cumberland Westmorland Antiq. Arch. Soc., N. Ser. 32, Carlisle 1932, pp. 149-51.

- Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies Britannia: a journal of Romano-British and kindred studies. No. 13, 1982, p. 410

- Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies Britannia: a journal of Romano-British and kindred studies. No. 14, 1983, pp. 290-292

- Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies Britannia: a journal of Romano-British and kindred studies. No. 15, 1984, p. 280

- Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies Britannia: a journal of Romano-British and kindred studies. No. 16, 1985, pp. 274-276

- Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies Britannia: a journal of Romano-British and kindred studies. No. 17, 1986, p. 437

- Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies Britannia: a journal of Romano-British and kindred studies. No. 18, 1987, p. 275

- Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies Britannia: a journal of Romano-British and kindred studies. No. 19, 1988, pp. 438,495

- Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies Britannia: a journal of Romano-British and kindred studies. No. 23, 1992, pp. 45-109

- Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies Britannia: a journal of Romano-British and kindred studies. No. 20, 1989, p. 335

- Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies Britannia: a journal of Romano-British and kindred studies. No. 21, 1990, pp. 320,366

- Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies Britannia: a journal of Romano-British and kindred studies. No. 22, 1991, pp. 299, 301, 235

- Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies Britannia: a journal of Romano-British and kindred studies. No. 25, 1994, p. 263

Remarks

- ↑ Sheard 2011, p. 122.

- ↑ R&C 129

- ↑ Rivet / Smith 1979, pp. 301–302, Jackson 1953, p. 39, Fulton 2005, pp. 15–31, Burnham / Watcher 1990, p. 51, Southern, 2016, Itinerarium Antonini / Iter II : "Der Weg from the entrenchments to port Rutupiae ", this lists all road stations between Hadrian's Wall and Portus Rutupiae (Richborough, England), including Luguvallo , 12 (Roman) miles from Castra Exploratorum (Netherby, Cumbria) and 14 miles from Voreda (Old Penrith, Cumbria ). The city is also the northern end point of Iter V : "The route from Londinium to Luguvalium on the wall, 433,000 steps", this time called Luguvalio and 36 kilometers from Brocavum (Brougham, Cumbria). The Lugubalia des Beda Venerabilis (approx. 730) is based on the Latin place name.

- ↑ Burnham / Watcher 1990, p. 51

- ↑ Charlesworth 1978, pp. 115-117, Wilson / Jones / Evans 1984 pp. 65 and 70, McCarthy 1974, pp. 102 and 242, St. Joseph 1951, p. 54, Ferguson 1893a, pp. 348-349, Shaw 1924, pp. 96-102; Simpson 1953, p. 234; Hogg 1955, p. 72, Bushe-Fox 1913, pp. 299-301, Charlesworth 1980, McCarthy 1991, Caruana 1992.

-

↑ Burnham / Watcher 1990, p. 55

- Cautius: RIB 943 ,

- Genius: RIB 944 ,

- Genius: RIB 945 ,

- Hercules: RIB 946 ,

- Unknown deity: RIB 947 ,

- Mars Belatucader: RIB 948 ,

- Mars Ocelus: RIB 949 ,

- Mars Victorius: RIB 950 ,

- Matrones: RIB 951 ,

- Mercury relief: RIB 952 ,

- RIB 953 ,

- Unknown deity: RIB 954 ,

- RIB 959 ,

- RIB 963 ,

- Milestone Harraby Bridge: RIB 2290 , RIB 2291 and RIB 2292 .

- ↑ Tab. Luguval. 16, Pearce 2004, pp. 49-50.

- ↑ Doubleday 1901, p. 285, Whellan 1860, p. 83, Burnham / Watcher 1990, p. 51, Bewley 1994, John of Fordun 1872, p. 52. In The Historians of Scotland, vol. IV.

- ↑ Frere Britannia p. 100, Tacitus, Agricola 17.2.

- ↑ Burnham / Watcher 1990, p. 331, Milestone Brougham: RIB 3526 .

- ↑ ND occ. XL, 29, Moffet 2011.

- ^ Nash Ford 1994, p. 263, McCarthy 1979, pp. 268-272, Birkhan 1997, pp. 951 and 1020, Burnham / Watcher 1990, pp. 51, 58.

- ^ McCarthy 1984

- ↑ McCarthy 1979, pp. 269-270

- ^ Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies, Britannia, No. 25, 1994, p. 263, Hodgson 2009, pp. 140-150.

- ↑ Burnham / Watcher 1990, p. 57, Moffat 2011, Potter / Johns 1992, p. 57, Tablet 250 McCarthy 2017.

- ↑ RIB 1125 , RIB 3458

- ↑ Burn 33; Brick stamp [LE] G VIIII

- ↑ RIB 3460 , RIB 3462

- ↑ Tomlin 1998, pp. 31-84, Tablet 671 .

- ^ RIB 946

- ↑ RIB 957

- ↑ ND occ. XL, 29

- ↑ North Pennines Archeology 2004, Shotter 2005, p. 69

- ↑ Milestone Brougham Castle: RIB 3526 , Gravestone Old Penrith: RIB 933 , Watcher 1995, p. 40.

- ^ Charlesworth 1978, p. 123

- ↑ Burnham / Watcher 1990, p. 55.

- ↑ Burnham / Watcher 1990, p. 55.

- ↑ Burnham / Watcher 1990, p. 55.

- ↑ Rivet / Smith 1979, pp. 301, 402, Charlesworth 1978, pp. 115-137, Caruana 1992, pp. 45-109, Lewis 1966, p. 125, Wilson / Jones / Evans 1984, pp. 65,66, 72-73, McCarthy et al. 1990, Hodgson 2009 pp. 140-150, Moffet 2011, Burnham / Watcher 1990, pp. 51-55, Colgrave 1940, Papia's tombstone from Gallows Hill: RIB 955 .

- ↑ Burnham / Watcher 1990, p. 55, Huntley 1992.

- ↑ Ferguson Transactions No. 12, 1893, pp. 365-374, McCarthy 1984, p. 72, Moffet 2011, Burnham / Watcher 1990, p. 55,

- ^ Hodgson: History of Northumberland pt II, vol. III, Newcastle 1840, JC Bruce: Handbook to the Roman Wall. 1957, p. 210, J. St Joseph: Air reconnaissance of North Britain. 41, 1951, pp. 52-65.

- ↑ St. Joseph 1951, p. 55, Welfare / Swan 1995, pp. 42–43.

- ↑ St. Joseph 1951, p. 54, Welfare / Swan 1995, pp. 38-39.

- ↑ Welfare / Swan 1995, pp. 30-31.

- ↑ Welfare / Swan 1995 pp. 43-44, St Joseph 1951 pp. 52-65.

- ↑ St. Joseph 51, 1961, pp. 120-121; R. Bellhouse: Transactions of the Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian & Archaeological Society, No. 53, 1953, pp. 49-51.

Web links

- Description of the town on Tynedale

- Luguvalium on ROMAN BRITAIN

- Luguvalium on Pastcape

- Location of the fort on Vici.org

| From the rampart to the port of Ritupiae . | Distance: 481 Roman miles | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| of Blatobulgium | [ Birrens ] | 12 | |

| to Castra Exploratorum | [ Netherby ] | 12 | |

| after Luguvalium | [ Carlisle ] | 12 | |

| after Voreda | [ Old Penrith ) | 14th | |

| after Bravoniacum | [ Kirkby Thore ] | 13 | |

| after Verterae | [ Brough ] | 13 | |

| according to Lavatrae | [ Bowes ] | 14th | |

| after cataractonium | [ Catterick ] | 16 | |

| to Isurium | [ Aldborough ] | 24 | |

| to Eboracum | [ York ], | [Location of Legio VI Victrix ], | 17th |

| after Calcaria | [ Tadcaster ] | 9 | |

| to Cambodunum | [ Slack ] | 20th | |

| after Mamucium | [ Manchester ] | 18th | |

| according to Condate | [ Northwich ] | 18th | |

| after Deva | [ Chester ], | [Location of Legio XX Valeria Victrix ], | 20th |

| according to Bovium | [ Tilston ] | 10 | |

| after Mediolanum | [ unknown ] | 20th | |

| after rutunium | [ Harcourt Park ] | 12 | |

| after Viroconium | [ Wroxeter ] | 11 | |

| to Uxacona | [ Redhill ] | 11 | |

| after Pennocrucium | [ Penkridge ] | 12 | |

| after Letocetum | [ Wall ] | 12 | |

| to Manduessedum | [ Mancetter ] | 16 | |

| to Venonae | [ High Cross ] | 12 | |

| to Bannaventa | [ Norton ] | 17th | |

| after Lactodurum | [ Towcester ] | 12 | |

| to Magiovinium | [ Fenny Stratford ] | 17th | |

| after Durocobrivae | [ Dunstable ] | 12 | |

| after Verulamium | [ St Albans ] | 12 | |

| after Sulloniacae | [ unknown ] | 9 | |

| to Londinium | [London] | 12 | |

| after Noviomagus | [ unknown ] | 10 | |

| after Vagniacae | [ Springhead ] | 18th | |

| after Durobrivae | [ Rochester ] | 9 | |

| according to Durolevum | [ unknown ] | 13 | |

| after Durovernum | [ Canterbury ] | 12 | |

| to the port of Ritupiae | [ Richborough ] | 12 | |