Aesica

| Great Chesters Castle | |

|---|---|

| Alternative name |

a) Aesica , b) Esica |

| limes | Britain |

| section | Hadrian's Wall |

| Dating (occupancy) |

Hadrianic , 2nd to early 5th centuries AD? |

| Type | Equestrian and cohort fort |

| unit |

a) Legio XX Valeria Victrix (building vexillation ), b) Legio VI Victrix (building crew), c) Cohors I Pannoniorum , d) Cohors VI Nerviorum , e) Cohors II (?) Gallorum equ. , f) Cohors VI Raetorum , g) Vexillatio Gaesatorum et Raetorum , h) Cohors II Asturum equitata |

| size | Area: 1.3 ha |

| Construction | Stone construction |

| State of preservation | square floor plan with rounded corners; Remains of the west and south gates and the fence as well as a cellar vault of the Principia are still visible |

| place | Halt whistle |

| Geographical location | 54 ° 59 '42 " N , 2 ° 27' 50.4" W |

| Previous | Vercovicium Castle (east) |

| Subsequently | Magnis Castle (west) |

| Upstream | Haltwhistle Burn ( Stanegate ) fort (southwest) |

| Aerial view of the fort area |

|---|

| Webaviation |

|

Link to the picture |

Aesica was a Roman fort of the auxiliary troops in County Northumbria , in the north-west of England , Parish Greenhead, hamlet Haltwhistle .

It belonged to the chain of fortresses of Hadrian's Wall ( per lineam valli ), which consisted of a total of 16 forts, and secured its central section. In contrast to most of the other camps along the wall, Aesica stood entirely south of the wall, alongside the foundations of the original wall and a mile fort that had been removed when the fort was built. The camp was believed to have been used by the Roman military from 128 to 400 AD.

Surname

The origin of the ancient place name is unclear. It may be derived from a Celtic deity and could mean "the place of Esus ". It is given in the Notitia Dignitatum ( Aesica ), on the Amiens Patera and in the cosmography of the geographer of Ravenna as Esica . The name Great-Chesters (= the great fortress) in use today probably comes from the early Middle Ages , when the Anglo-Saxons took over rule in Britain. Chester ([ ˈtʃɛstə ]) was the name given to a place enclosed by a wall in their language. Presumably the walls of the fort remained upright long after the Romans left, as it was initially spared from stone robbery due to its remote location.

location

Aesica is the ninth link in the fortress chain of Hadrian's Wall ( vallum aelium ). The fort is about 1.5 miles north of the town of Haltwhistle, north of the Tyne , in a pasture west of Great Chesters Farm. To the south of it stood the Haltwhistle Burn small fort on Stanegate . In the late 2nd century the region belonged to the province of Britannia inferior , from the 4th century to the province of Britannia secunda . The fort is now part of Northumberland National Park.

Research history

In 1724, the Scottish antiquarian Alexander Gordon reported that some of the fort's wall passages were still thirteen feet (3.9 meters) high. The remains of the camp and vicus were also described by John Horsley in 1732. In 1807 Lingard reported on the cellar vault in the Principia and the discovery of an altar dedicated to the Disciplinae . The first excavations were carried out in 1894. By 1897, the south and west gates, the corner towers of the northwest and southwest corners as well as the most important functional buildings and a thermal bath were uncovered. Most of the remains of the camp were destroyed in the course of the excavations. At the south gate you came across a hoard that contained numerous decorative elements. These included an enameled brooch in the shape of a rabbit, a gold-plated Celtic brooch, a silver necklace with a pendant, a gold ring and a bronze ring with a Gnostic symbol. Replicas of these objects can be seen in the Museum of Antiquities in Newcastle. During this excavation, the camp headquarters ( principia ) were also partially exposed, including the remains of the cellar vault under the flag sanctuary. The walls of a barracks block were observed southwest of the Principia. In 1908 a watermill was discovered at Haltwhistle Burn. The remains of her wooden mill wheel were also preserved. As a result, their millstones could also be recovered. They are now in the collection of the Chesters Museum. In 1925, the northwest corner of the fort was examined again. In 1939 Frank Gerald Simpson came across the remains of Mile Fort 43 . In 1966 a field inspection was carried out along the aqueduct. Members of the Society of Antiquaries of Newcastle made a second visit in 1971 to verify the 1966 results. From 1987 to 1988 the aqueduct was re-measured.

Find spectrum

Aesica brooch: The piece of jewelery is one of the most famous finds of Celto-Roman Britain and was discovered in September 1894 during an excavation in the western guard room of the south gate, about 0.9 meters from its north wall. It is made of gilded bronze and was cast in two parts. The upper part is formed by a square head plate with a curved arch, the lower part from an elongated, foot-shaped plate. The approximately ten centimeter long brooch is decorated with spiral ornaments based on Celtic models. It is believed to have been made in a workshop in northern Britain, possibly in Yorkshire , around AD 70 or 80. Such pieces were worn in pairs on the shoulders to attach an upper garment. Similar brooches were also found on the continent in the Rhineland, in Gaul and Pannonia. Although there are many parallels to its shape and decoration in Great Britain, the Aesica brooch is so far unique in its execution.

Inscriptions: 31 inscriptions have been discovered in Great Chesters to date. They include eleven consecration altars, a base for statues of various gods, six building inscriptions (of which only three could be dated), seven tombstones, six other unspecified inscription stones including a centurial stone with the number XLVIII "Forty-eight". The inscriptions were created between 127 and 244. Two tombstones and a Iupiter altar were used in the commandant's house for a second time.

development

In 122 Emperor Hadrian ordered a barrier wall to be built in northern Britain, reinforced by watchtowers and forts, from the Tyne to the Solway Firth, to protect the British provinces from the constant incursions of the Picts from the north. Most of the wall was built by soldiers from the three legions and men of the Classis Britannica stationed in Britain .

Little is known about the history of the fortress. It is believed that there was a temple or shrine of the Celtic god of war there before Hadrian's Wall was built. Aesica was supposed to secure the valley of the Haltwhistle Burn and a transition over the Winshield Ridge (the so-called Caw Gap). The fort was built in the middle of the 2nd century AD, but only after the Hadrian's Wall was completed in this region. Together with Carrawburgh , it was one of the last forts built on the wall. The building inscription recovered around 1851 near the east gate is dedicated to Hadrian and describes him as the "father of the fatherland" ( pater patriae ). The emperor had held this title since 128, so the gate and probably the rest of the fort must have been built between 128 and 138. Near the camp, at the point where the Military Road crossed Haltwhistle Burn, stood a Roman watermill. Perhaps from here the crew were also supplied with flour for their bread rations. Another building inscription discovered in the fort reports that the granary was renovated in 225, during the reign of Severus Alexander . In the late fourth century Britain slipped more and more out of the control of the Roman central government in Ravenna . As the entry in the Notitia Dignitatum suggests, like most other ramparts, it was probably not abandoned by the military until the early 5th century. The last regular units of the Roman army withdrew from Britain around 410. The fortress was eventually destroyed over the centuries by stone robbery, for building agricultural buildings and field walls.

Fort

In contrast to some fortifications in the eastern sector, some of which protruded beyond Hadrian's Wall, Aesica stood entirely south of the wall. It had the long rectangular floor plan with rounded corners (playing card shape) typical of medieval forts and was oriented from east to west. The camp measured 108 meters from north-south, 128 meters from east-west and thus only covered an area of 1.3 hectares. With the Pons Aelius and Congavata castles, it is one of the smallest castles on the wall. The long side was oriented towards Hadrian's Wall. The north-east corner of the fort is now built over with farm buildings. The military road that accompanied the wall in the south reached Aesica at the east gate (main gate porta praetoria ), formed the main camp road ( via principalis ) and led from the west gate to the nearest fort Birdoswald ( Banna ). A branch street, starting from the south gate, connected the fort with the Stanegate . The remains of the fort are now heavily overgrown by vegetation.

Enclosure

The foundations of the 2.1 meter wide wall and the surrounding trenches are still relatively well preserved. On the west side they are recognizable as slight elevations or depressions. It was probably supported at the rear by an earth ramp, which also served as a battlement. Unusually for a fort on Hadrian's Wall, it was probably surrounded by several moats. Four have been identified on the west side, while the south and east walls were protected by just one moat. This suggests that the builders of the fortress viewed the flat terrain to the west as the greatest weak point in the defense. The western trenches are covered by the wall at their northern end. The fort was probably expanded again during its existence (see Fort Onnum ), or they were excavated before the mile fort was demolished. On the south side it seems that the moat there disturbed the vallum , which was also built before the fortress was built.

Gates

One could enter the fort through four gates placed in the north, south, east and west. The north and south gates were not placed centrally, but were shifted slightly to the east. All were flanked by two square towers protruding slightly from the wall. Each had two passages, separated by two support pillars ( spina ) on the front and back. The guard rooms were in the flank towers. The gates could be locked with double-leaf wooden gates.

East Gate: The building inscription from him has been preserved, which proves that the fortress was built in the time of Hadrian (now in the Chesters Museum).

West gate: A structural feature from its late antique construction phase can still be recognized on this gate construction. It was last renovated under Septimius Severus . During the reign of Constantine I , a passage was walled up. At a later date, the second was also completely blocked. These walls can still be seen. Such blocking measures could also be observed at other ramparts. They could be explained by the continuous reduction in crews in late antiquity . The first excavators usually systematically cleared later additions aside in order to expose the original building structures. H. usually the hadrianic ones. In this way, more precise floor plans could be determined. Unfortunately, this also destroyed valuable references to the later construction phases in the history of the camp. Many of them were removed because they were believed to be rubble. With this gate everything was left as it was found, as the passage blockages contrasted strongly with the more massive masonry of the foundations of the gate towers. An unusually large stone block in the northern passage suggests that the upper part of the gate for the extraction of stone material had been partially torn off as it had lost its function anyway.

South gate: A safe deposit box in the western guard room of the south gate (from the end of the 2nd century) contained various items of jewelry (see above). In the eastern flank tower there is still a Roman altar on which the relief of a jug is carved. It is one of the few specimens in Great Britain that is still in its place of discovery. A little to the side you can see a stone block on which two soldiers are depicted on a heavily weathered relief.

North Gate: This gate has not yet been exposed.

Towers

The walls of the fort were additionally reinforced at each of its corners with a square tower attached to the inside. The entrances were on the ground floor. It is not known whether there were stone staircases or only wooden ladders inside. The towers were probably ten meters high. It is difficult to say whether the upper floor was covered with a roof or open and provided with a crenellated crown. So far, there are no relevant archaeological finds in order to be able to reconstruct their appearance beyond doubt. The south-west and north-west specimens of the corner towers are still visible. Intermediate towers could not be proven archaeologically.

Interior development

The fort had all the standard functional buildings of a mid-imperial fort, a camp headquarters or administration building ( principia ), a commanders' house ( praetorium ), a granary ( horraeum ), and barracks for officers and men ( centuriae ). The flag sanctuary ( aedes ), the basement below, the office ( officia ) and the transverse hall ( basilica ) were uncovered from the camp headquarters in 1894 . Today only two stone arches of the vault of the cellar can be seen under the flag sanctuary. The only remnant of the building that is still visible inside the fort. The granary was probably north of the camp headquarters, the commandant's house south of it. It was also only partially exposed. Its walls contained numerous spoils . The excavations also revealed traces of six late Roman crew houses in the southwest of the fort area. They resembled the huts of the late 3rd century that were also discovered in neighboring Housesteads . Their floor plans can still be seen from the air. At the western wall one also came across square building structures (bakeries or latrines?) Whose function has remained unknown.

aqueduct

Fresh water was supplied via an aqueduct that was fed from the upper reaches of the Caw Burn further north. Its remains can still be seen in some places as shallow depressions. The aqueduct was designed as a 9.6 km long, one meter wide and deep canal. The difference in height from the source to the fort is approx. 320 meters. The numerous natural obstacles (slopes) required a water pipe laid out in wide serpentines . It started at Tom's Pool, northeast of Saughy Rigg and crossed a valley at Benks Bridge. There the line must have been routed over a bridge construction made of wood or masonry. The course of the last line section north of the fort is not known. Due to the steeply sloping terrain, the water may have flowed behind a dam or in a culvert . It is doubtful whether the aqueduct ended inside the fortress; possibly it emptied into the moat at the NW corner tower.

Hadrian's Wall

At the end of the 1930s, the remnants of Mile Fort 43 , which had been built before the fort , were found in the north-western camp area . It was built exactly on the foundations of a wide version of the wall. When examining the wall foundations, the archaeologists found that they were up to three meters thick. Why the north wall of the fort was not built on the foundations of the original ramparts is unclear. It is assumed that the later, only 2.1 meters wide north wall of the camp was built further south because the mile fort and the wall were supposed to protect the soldiers involved in the construction from sudden attacks by the Caledonians. They could therefore only be completely removed after the fort had been completed. The course of the southern moat ( vallum ) could be demonstrated over a short distance south of the camp. It was crossed by the connecting road to Stanegate and was tw. covered by the fort walls. Although - in contrast to Carrawburgh - it was still in the military exclusion zone. Another solid proof of the subsequent construction of the fort.

garrison

Aesica hosted several cohorts of auxiliary troops ( auxilia ) during its existence . In late antiquity, the castle's occupants were among the Limitanei . Legionaries were probably only used here for building projects. They were usually stationed in their main camps during the winter months and were probably only assigned to Hadrian's Wall in summer.

The following units either provided the crew for the fort or could have stayed there temporarily:

| Time position | Troop name | description |

|---|---|---|

| 2nd century AD | Legio vicesimae Valeria Victrix (the twentieth Valerian Legion, the Victorious) | A Jupiter Dolichenus altar (127–150) discovered in the Praetorium of Aesica in 1897 was donated by a centurion of the Legio XX , Lucius Maximius Gaetulicus. |

| 2nd century AD | Legio sextae Victrix (the sixth legion, the victorious) | A tombstone for a certain Nigrina discovered at Aesica around 1875 was commissioned by Aurelius Casitto, a centurion of Legio VI . |

| 2nd century AD | Cohors prima Pannoniorum (the first cohort of the Pannonians ) | It is possible that soldiers from the province of Pannonia (today's Austria-Hungary-Serbia) stood at Great Chesters sometime shortly after the fort was completed. Their presence in this region is known from a tombstone for Dagvalda, placed in the late 2nd century by his wife Pusinna, which was found in the neighboring Mile Fort 42 . However, the tombstone was used there as an accessory for a hearth (so-called Spolie ). The serial number of the unit was not given in the inscription. The researchers can therefore only assume that the deceased was a member of this cohort. John Clayton (1792–1890) assumed that the stone originally came from the fort's burial ground. |

| 2nd century AD | Cohors sextae Nerviorum (the sixth cohort of the Nervier ) | The force was originally recruited from members of the Nervii tribe, resident in the province of Gallia Belgica . It was believed to be the first garrison unit for Great Chesters Castle. In the middle of the 2nd century she was transferred to Rough Castle on Antonine Wall. There the soldiers erected u. a. the principia of this camp. The unity is otherwise mentioned for Britain in an inscription from the early 3rd century from Brough by Bainbridge in Yorkshire and in the late antique Notitia Dignitatum . From the inscription discovered in Great Chesters around 1801, the rank and name of one of its commanders, the Prefect Gaius Iulius Barbarus , is known. |

| 2nd century AD | Cohors secundae (?) Gallorum equitata (the second partially mounted cohort of the Gauls) | The unit is known for Great Chesters from the inscription of a fragment of a Jupiter altar discovered in 1907. Their serial number was no longer legible on the inscription. It was originally set up with members of tribes living in central and northern Gaul. Presumably she came to the island with Hadrian's escort. The unit is also mentioned on five military diplomas (dated 122–178). For Britain there are four other related inscriptions from Old Penrith Castle in Cumbria (178–249) where this troop was stationed afterwards. |

| 2nd century AD | Cohors sextae Raetorum (the sixth cohort of the Raetians ) | This 500-strong unit was located in Great Chesters in the late 2nd century during the reign of Marcus Aurelius . She was probably recruited from several Rhaetian tribes in today's Austrian-Bavarian-Swiss Alpine regions. These included u. a. the Vindeliker , the Estionen , the Licates, the Genauni , the Briganten , the Venones and the Kalukonen . The troop is only mentioned on a late second century (166-169) inscription from Great Chesters. Nothing is known about their further activities in Britain. |

| 3rd to 4th century AD | Vexillatio Gaesatorum et Raetorum (a department of the Gaeseter and Raetians) | The fort garrison was possibly reinforced in the late 3rd century by a vexillation of irregular Gallic and Rhaetian mercenaries. The presence of the troops in Britain is only known from the inscription on an altar of Fortune discovered in 1908 from the thermal baths of Great Chesters. It was donated by this unit. The name of one of their centurions , Tabellius Victor, has been passed down from this consecration altar. |

| 3rd to 5th century AD | Cohors secundae Asturum equitata (the second partially mounted cohort of Asturians ) | The five hundred strong troop provided the garrison from the third century. They were originally recruited from a Celtic tribe who settled in northern Spain. The troop may have been in Llano in Wales ( Bremia ) before . Their presence in Great Chesters is attested by a building inscription. She reports that her soldiers were instrumental in rebuilding the fort's granaries under the command of the legionary centurion Valerius Martialis (of which legion is unknown). The unit is also mentioned as the garrison of Aesica in the Notitia Dignitatum (4th century), in the troop list of the Dux Britanniarum . There it is, however, given the order number I, probably a copying error by the medieval copyists. The rank of the officer in command at the time, a tribunus , is also known from the Notitia . Since the troops still appear in this late antique document, they could have stood here until the final withdrawal of the Roman army from Hadrian's Wall. |

Vicus

A civil settlement ( vicus ) spread to the south and west of the glacis of the fort . Their remains have never been scientifically studied, so very little is known about them. The only remaining identifiable features are their once artificially built platforms and terraces. Remnants of the settlement had also been observed in a field south of the fort. However, they are likely to have been largely destroyed by the intensive agricultural use of the area. The contours of the buildings south of the fortress and east of the road leading from the south gate can also be seen in aerial photographs.

Thermal bath

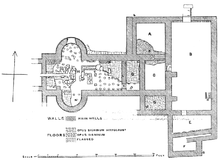

The bathhouse ( thermae ) , discovered at the end of the 19th century, stood about 92 meters south-east of the fort, east of the road connecting to Stanegate. It was a row type building and had all the relevant functional rooms (see diagnosis plan):

- Changing room and fitness room ( apodyterium or gymnasium , room B),

- Latrine ( lavatrina , room E),

- Cold bath ( frigidarium , rooms C and D),

- Sweat room ( laconicum , room A),

- Hot bath ( caldarium )

- Leaf bath ( tepidarium , rooms G and H).

Fresh water was supplied via the aqueduct. The hot bath had two exactly opposite apses on the north and south walls. Their water basins were heated via a T-shaped channel, starting from a boiler room ( prefurnium ) behind the west wall. Some of the stone pillars were still preserved from the hypocaust heating . A coin hoard from the 3rd century AD was recovered during the excavations in the hot bath. In 1908 an altar of the goddess Fortuna was found . Also worth mentioning are the remains of a glazed window, about 1.5 meters high and 1.2 meters wide, which was discovered in situ (fall position) in the northern apse of the hot bath. The corresponding window ledge was 0.3 meters above the floor, measured 4 meters on the inside and narrowed to 3 meters towards the outer wall. More broken glass was later found inside the building. In 1984 aerial photographs of the stone foundations were made. The bath house was then backfilled with earth by the Royal Commission of Heritage Memorial in England (RCHME) to prevent further destruction through erosion.

Burial ground

To the west of Walltown Mill, several headstones were found in a cattle pasture at Mill Hill between 1742 and 1817. Presumably the soldiers and the residents of the vicus buried their dead there. One had the relief of a woman. The gravestone of the soldier Aelius Mercurialis was about 400 meters from the road connecting south to the Stanegate. He may have served as scribe ( cornicularis ) for the Asturian cohort. The tombstone was donated by his sister Aelia Vacia. She apparently lived very close to her brother, perhaps even in the Great Chesters civil settlement. It is also possible that her father was already a soldier in the local garrison, later married a British woman and settled with her in Aesica after he left the army . Two tombstones were placed for young girls, one for Pervica, the other by Aurelia Scintilla for her sister Aurelia Caula.

See also

literature

- John Hodgson: History of Northumberland. 1840, part 2, vol. 3.

- Guy de la Bédoyère : Hadrian's Wall: history and guide, Tempus, 1998, ISBN 0-7524-1407-0 .

- John Collingwood Bruce, Roman Wall, Harold Hill & Son, 1863, ISBN 0-900463-32-5 .

- John Collingwood Bruce: Handbook to the Roman Wall . 12th edition. Newcastle-upon-Tyne 1966.

- JC Bruce: Handbook to the Roman Wall . Ed. IA Richmond, 11th Edition, 1957.

- Frank Graham: The Roman Wall, Comprehensive History and Guide. 1979, ISBN 0-85983-140-X .

- GDB Jones, DJ Woolliscroft: Hadrian's Wall From the Air. Tempus, Stroud 2001.

- Ronald Embleton, Frank Graham: Hadrian's Wall in the Days of the Romans. Newcastle, 1984, pp. 172-179.

- Robin George Collingwood, RP Wright: The Roman Inscriptions of Britain. 1. Inscriptions on stone. Oxford 1965.

- AJ Evans: Society of Antiquaries of London Archaeologia: or miscellaneous tracts relating to antiquity. No. 55, 1896, p. 177.

- Dorothy Charlesworth: The Aesica hoard of jewelery, Great Chesters, Northumberland . 1973.

- Eric Birley: Research on Hadrian's Wall. 1961.

- Eric Birley: The Beaumont Inscription, the Notitia Dignitatum, and the Garrison of Hadrian's Wall. Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society, Transactions of 2nd Series. No. 39, 1939.

- Ian Archibald Richmond : Society for Promotion of Roman Studies. The journal of Roman studies. No. 35, 1945.

- D. Peel: Council for British Archeology Group 3: Archaeological newsbulletin for Northumberland, Cumberland, Durham, Westmorland and Lancashire-north-of-the-sands. 1, 1972.

- Peter Salway: The frontier people of Roman Britain . Cambridge classical studies, 1965.

- JP Gibson: Archaeologia Aeliana: or miscellaneous tracts relating to antiquity. No. 24, 1901-1902, pp. 19-64.

- John Kenneth Sinclair St. Joseph: Air Reconnaissance of North Britain. In: The Journal of Roman Studies . 1951.

- CE Stevens: The building of Hadrian's wall. Archaeologia Aeliana, Issue 4, 26, 1948, pp. 1-46.

Remarks

- RIB = Roman inscriptions in Britain

- ↑ Guy de la Bedoyere, 1998, p. 89, R&C 150, a Roman bronze vessel (found in 1949 in Amiens , France), inscription: MAIS ABALLAVA VXELODVNVM CAMBOG… S BANNA ESICA.

- ^ John Horsley, 1732, Britannia Romana, RIB 1723, p. 150, D. Peel, 1972, p. 11, JC Bruce, 1966, pp. 143-145.

- ↑ RIB 1748 , RIB 1750 , RIB 1751 , Eric Birley, 1961, pp. 188-191 and p. 267, JC Bruce, 1966, pp. 143-145.

- ↑ RIB 1736 , Guy de la Bedoyere, 1998, pp. 89-90, JC Bruce, 1966, p. 143, CE Stevens, 1948.

- ↑ Guy de la Bedoyere, 1998, p. 89

- ↑ Guy de la Bedoyere, 1998, p. 90

- ↑ Guy de la Bedoyere, 1998, pp. 90-91, JC Bruce, 1966, p. 145.

- ↑ Guy de la Bedoyere, 1998, p. 90, JC Bruce, 1966, pp. 145-146.

- ↑ IA Richmond 1945, pp. 80–81, Guy de la Bedoyere 1998, p. 91, JC Bruce 1966, p. 148.

- ↑ Guy de la Bedoyere, 1998, p. 90

- ↑ RIB 1725

- ^ RIB 1746 , JC Bruce, 1966, p. 146.

- ↑ RIB 1667 , RIB 2042 (253-258), Eric Birley 1939c, p. 226.

- ↑ RIB 1731 (statue base)

- ^ RIB 1727

- ↑ RIB 1737

- ↑ RIB 1724

- ↑ RIB 407 , RIB 408 , ND Occ. XL, 42: Tribunos cohortis primae Asturum, Aesica.

- ↑ JP Gibson, 1901-1902, p. 43, P. Salway 1965, pp. 92-93, JC Bruce, 1957, p. 155.

- ↑ JC Bruce, 1957, p. 155, RG Collingwood / RP Wright, 1965, p. 541, JP Gibson, 1901-1902, pp. 19-64, JC Bruce, 1966, p. 146.

- Jump up ↑ RIB 1742 , RIB 1743 , RIB 1745 , RIB 1747 , John Hodgson, 1840, p. 203, RG Collingwood / RP Wright, 1965, pp. 547-548.

Web links

- RIB Roman Inscriptions of Britain inscription database

- Aesica on ROMAN BRITAIN

- Description of the Amiens Patera on ROMAN BRITAIN

- Aesica Castle on PASTSCAPE

- Aesica on Historic England

- Part VIII on You Tube, The Wall from Arbeia to Maia. Film production with 3D-CGI models, images and explanation of the individual Roman castles along Hadrian's Wall (English).

- Relief on the south gate

- Odyssey of Archeology The Wall

- Hadrian's Wall photo album on Flickr

- Satellite photo of the fort area, location of Roman monuments on Vici.org.

- John Collingwood Bruce: The Roman Wall: A Description of the Mural Barrier of the North of England, 1867, with numerous pictures of wall remains, altars, inscriptions etc.