Brocolitia

| Carrawburgh Castle | |

|---|---|

| Alternative name |

a) Brocolitia , b) Brocoliti , c) Brocolita , d) Procolita |

| limes | Britain |

| section | Hadrian's Wall |

| Dating (occupancy) |

Hadrianic , 2nd to late 4th century AD |

| Type | Cohort fort |

| unit |

a) Legio VI Victrix (Bau vexillation ), b) Cohors I Tungrorum , c) Cohors I Aquitanorum , d) Cohors I Cugernorum , e) Cohors I Frisiavonum , f) Cohors II Nerviorum , g) Cohors V Raetorum , h) Cohors I. Batavorum |

| size | Area: 1.5 ha |

| Construction | Stone construction |

| State of preservation | square floor plan with rounded corners, foundations of the west gate and the west wall partly. visible |

| place | Newbrough / Chollerford |

| Geographical location | 55 ° 2 '9.6 " N , 2 ° 13' 22.8" W |

| Previous | Fort Ciliurnum (east) |

| Subsequently | Vercovicium Fort (west) |

| Backwards | Newbrough Fort (Stanegate) (southwest) |

| Aerial view of the fort area |

|---|

| Webaviation |

|

Link to the picture |

Brocolitia or Procolitia was a Roman fort of the auxiliary troops in County Northumbria , hamlet (Hamlet) Collerford des Parish Newbrough in north-east England .

It belonged to the chain of fortresses of Hadrian's Wall ( per lineam valli ) consisting of a total of 16 forts and secured its eastern section. The camp was used by the Roman military for about 300 years, probably from 130 to 400 AD. In the provincial Roman archeology , the excavation site is known for three Romano-British places of worship located near the camp.

Surname

The place name comes from the Celtic and means either "badger hole" (JC Bruce), "place in the heath" or "rocky place" (Guy de la Bedoyere). The name appears in the Notitia dignitatum ( Procolitia ) of the late 4th century and is mentioned in the cosmography of the geographer of Ravenna from the 7th century as Brocoliti between Celunnum (Chesters) and Velurtion (Housesteads).

location

Brocolitia is the seventh link in the chain of fortresses of Hadrian's Wall ( vallum aelium ) and is located in the area of Tynedale district, County Northumberland, 1.5 miles west of the hamlet of Chollerford on the B6318, on the central section of the wall. It stood in Tepper Moor , at the northernmost point of the “Limestone Corner” wall section, a Roman mile west of Mile Fort 30 . There is a hamlet nearby , Carrawburgh, halfway between Sewingsshield and Chollerford. The fort area is now on the pastures of the Carrow farm (Carrow House). The location offered excellent views south over the valley of Maggie's Dene Burn. Road connections existed to the camps of Cilurnum (Chesters), Vercovicium (Housesteads), Vindolanda , Newbrough on Stanegate and Coesike. From 212/213 the region around Brocolitia belonged to the province of Britannia inferior , from the 4th century to the province of Britannia secunda .

Research history

The fort was first examined and described by John Horsley in the mid-18th century. He found that its eastern and western side walls were built at right angles to the wall and that the camp did not protrude to the north. He also reported traces of a vicus on the west side and the presence of a well. The first excavation was carried out at the end of the 19th century by John Clayton (1792–1890). In 1873 he was able to locate and examine the camp bath. In 1875 a coin hoard consisting of 66 denarii from the time from Marcus Antonius to Geta was discovered under a large stone in the center of the fort . In 1876 the remains of the southwestern intermediate tower were found. In the same year, workers in a lead mine discovered the "Coventinas Well" well, which was then uncovered by Clayton and John Collingwood Bruce. Bruce published a preliminary excavation report in the edition of the Newcastle Daily Chronicle of October 23, 1876. In 1934 a site inspection revealed that the southern moat of the wall ( vallum ) had been filled in when the fort was built. The mithraium was discovered in 1949 and exposed in 1950 by I. A. Richmond and J. P. Gillam. In 1960, a nymph shrine was discovered right next to the mithraeum . In 1964 excavations were carried out in the visitor car park. From 1967 to 1969 David J. Breeze conducted exploratory excavations for Durham University in Carrawburgh. Research on Brocolitia was summarized by Birley in 1961 and Charles Daniels in 1978. In 1984, the RCHME Newcastle made a plan of the fort and its surroundings, along with a full report on the state of preservation of the remains. In the same year remains of the south and east walls of the Conventina spring could be observed. At the end of the 1990s, aerial photographs were taken of the fort area.

Inscriptions and spectrum of finds

To date, 48 Roman inscriptions from the Carrawburgh area have become known. They were on 31 consecration altars, five building inscriptions (one damaged, undated), four centurial stones and six gravestones or grave inscriptions.

The finds from the Coventina shrine are particularly noteworthy , including a three-part stone relief of the goddess. A huge number of Roman coins and votive offerings were found in the spring basin, many of which, however, were stolen because Clayton had deposited them in a pit next to the spring overnight. When finally up to 6.5 kg of coins had been recovered from the source shaft, it was initially thought that a hoard had been struck, which had been sunk there because of a barbarian attack or the like. Later, however, it turned out that these were offerings for the goddess that must have accumulated here over a long period of time. A total of 13,487 coins (four of gold, 184 of silver, the rest of copper bronze) were seized. Many of them were worn out from years of use. They dated from the early reign of Augustus to the late 4th century. These coins included more than three hundred Aes from the time of Antoninus Pius , minted to mark the crackdown on a revolt of the northern British tribes in 155. These coins showed Britannia with her head bowed and a vexillum in hand. The final coin came from 388. Clayton had 3000 heavily worn specimens melted down and made an eagle sculpture (“Coventina's Eagle”) for his library (today in the Chesters Museum). The rest of the coins were given to the British Museum in London in the 1960s .

The other votive offerings included animal figures made of bronze, cloak fibulae ( fibulae ), rings, pearls, glass vessels, two clay incense burners with 'Augusta Coventina' carved into them, and scraps of leather. These included metal pegs (probably a symbol of birth) and sculptures of horses and dogs. The horse was a symbol of fertility, while the dog stood for the god of healing Asclepius . The majority of the artifacts are now in the collection of the Chesters Museum.

development

122 ordered the Emperor Hadrian to build a barrier wall in northern Britain, reinforced by watchtowers and forts, from the Tyne to the Solway Firth, to protect the British provinces from encroachments by the Picts from the north. Most of the wall was built by soldiers from the three legions stationed in Britain and the Classis Britannica .

The Brocolitia camp was almost certainly not built until after Hadrian's Wall was completed, probably between 130 and 132, and was built by members of the Legio VI Victrix . This assumption is substantiated by the discovery of an inscription mentioning Sextus Iulius Severus, the governor who officiated in Britain after 130. One of the reasons for this was the decision of the army command to move the crews of the Stanegate fort directly to the wall. The neighboring forts of Chesters and Housesteads were probably too far apart for the Roman strategists . The Mithraeum was probably destroyed at the end of the 3rd century during an incursion by the northern barbarian tribes. These took advantage of the rebellion of the usurpers Carausius and Allectus for a plundering campaign, since most of the units of the Wall Garrisons 296 had marched in the southeast to repel an invasion of the imperial troops. The fort was probably occupied by the regular military until the late 4th century. The last visible remains were demolished in the early 18th century by construction crews of the British Army under General George Wade (1673–1748) to extract material for the construction of an artillery road (today's B6318). The fort area is now privately owned, but freely accessible to visitors.

Fort

The fortification measured about 140 meters (north-south) × 110 meters (east-west), covered an area of 1.6 hectares and had the square floor plan with rounded corners (playing card shape) typical of the middle imperial era. The excavations at the end of the 1960s revealed that the camp probably went through three construction phases. Phase II could u. a. can be dated to the year 200 by ceramic shards. There was no evidence that it was still used by the military after 368. The rampart formed the north wall of the fortress. In contrast to the neighboring cavalry fort, it did not jut out over the wall to the north. The walls were broken through by a gate on each side. The east and west gates were not in the center of the wall, but were shifted slightly to the north as they were adapted to the course of the Wall Street or Military Street (also the via principalis of the camp). As a result, the retendura of the camp was somewhat larger than that of comparable forts. The camp covered the original course of the south trench ( vallum ). Today only the fort platform and some 0.5 meter high elevations at the southern end of the western wall are visible.

Enclosure

The fence consisted of a stone wall that was supported at the rear by an earth ramp. The latter also served as a battlement. On the west side, the fort wall is still a few rows of stones high (approx. 1.0 to 3.2 meters). Visible masonry is otherwise still on the south side, the remains of the northern flank tower of the west gate and a tower between the west gate and the south-western corner of the fort and on the B6318. The walls were reinforced with four corner towers set on the inside and probably eight intermediate towers (two on each side) with a square floor plan. The intermediate tower on the west wall, south of the west gate, was partially ten rows high when it was discovered in the late 19th century. A building inscription (now Chesters Museum) found in the lower layers of its western wall reports that 24 feet of the wall was built by the Thruponian centurion. The lower two rows were made a little wider. The north wall is now under the B6318 and could not be examined. The camp had the standard four main gates with - presumably - two passages, divided by two support pillars ( spina ) and two square side towers each; the porta Praetoria in the north, the two portae principales at each end of the via principalis from east to west, and the porta decumana in the south. One of the passages of the south gate was later blocked with stones from demolished buildings. The fort was also surrounded by a double moat to prevent it from approaching. The width of the berm was about four meters. For most of the periphery it is still visible as a terrace - around two meters below the crest of the wall. A third ditch might also exist. The southwest section of the trenches is still clearly visible.

Interior development

The buildings were also completely destroyed over time by stone robbery, agriculture and dredging. Only fragmentary remains have survived, including a large stone with a carved phallic symbol. South of the main road running from east to west, at the west gate, you came across the western side wall of a warehouse ( horreum ). The camp headquarters ( principia ) resembled that of Arbeia . Excavations on its south and west sides of the camp headquarters were made in the late 1960s. Subsequent changes to rooms VI and VIII were found. However, they could not be dated. They were probably due to the subsidence of the heaped ground above the former vallum . The hypocaust heating in room II seems to have never been completed.

Hadrian's Wall

The section of Hadrian's Wall at Brocolitia was built in the narrow version. After the fort, the wall leads over hilly terrain in a straight line to the Sewingshields Grags. At Carrawburgh, the remains of the wall are still under the B6318, but before it ascends to the Whin Sills, 3.2 km west, the road turns south into a valley and takes the easier route west there. The wall, on the other hand, leads over the ridge of the Sewingshields Grags to the valley of the Knag Burn, where it reaches the Housesteads fort ( Vercovicium ).

garrison

Brocolitia housed a number of auxiliary units of various origins in the course of its existence. Their names could be identified from the numerous epigraphic sources that were found there. The following units provided the crew for the fort or could have stayed there for a limited time:

| Time position | Troop name | description |

|---|---|---|

| 2nd century AD |

Legio sextae Victrix ("the sixth, Legion, the victorious") |

This legion was not permanently stationed here, one of its vexillations was probably busy with construction work in the fort. A total of four inscriptions from Brocolitia are known that refer to the Legion. An altar dedicated to Coventina had been donated by soldiers of the Sixth. Furthermore, three centurial stones from this section of Hadrian's Wall are known, which were set by this legion. Perhaps another vexillation had been assigned to the fort for repairs during the late second century, possibly after the retreat from Antonine Wall and the associated reoccupation of Hadrian's Wall. |

| 2nd century AD |

Cohors prima Aquitanorum ("the first cohort of the Aquitanians ") |

This cohort was originally recruited from various Aquitaine tribes in Gaul. Men from today's regions of Guyenne and Gascogne in south-west France. The force had a nominal strength of five hundred men ( cohors peditata quingenaria ). You must have provided the first crew for Carrawburgh. The cohort was posted to the Pennines in the small fort of Brough on Noe around the middle of the second century . It is therefore also possible that one of their vexillations was in an as yet undiscovered camp near Bakewell. In late antiquity, it stood in the Saxon coastal fort Brancaster ( Branodunum ), on the north-west coast of Norfolk . The unit is known for Brocolitia only from an inscription found on site. It is a fragment of a stone tablet that was found in the north-east corner of the fort in 1833. According to the inscription, the tablet was placed by this unit under their commandant Cornelius 130. |

| 2nd century AD |

Cohors prima Tungrorum millaria ("the first cohort of Tungerer , 1000 men strong") |

A cohort of the Tungrians from eastern Belgica . Today the landscapes of Brabant and Hainaut in Belgium. It is likely that this unit was divided between the castles of Carrawburgh and Chesterholm ( Vindolanda on Stanegate ). It stood between 139 and 161 on Antonine Wall in the castles of Cramond and Castlecary. After the Antonine Wall was abandoned, it was moved to Housesteads Fort ( Vercovicium ) and stood there until the end of the fourth century. The presence of this unit in Brocolitia is known from an altar inscription for Hadrian, donated between 122 and 138. |

| 2nd century AD |

Cohors prima Cugernorum ("the first cohort of Cugernians ") |

The unit had a strength of 500 men and was recruited from the Cugerni tribe in the Germania Inferior province . They settled in what is now the Meuse department and on the Rhine . Carrawburgh could have been their first base on Hadrian's Wall. In the middle of the 2nd century it was probably moved further north, to Newbridge near Cramond in Scotland. After abandoning the Antonine Wall, she occupied the Newcastle camp ( Pons Aelius ). The unit is known from an altar inscription for the goddess Coventina found on site. It was donated by one of its commanders, Aurelius Campester. |

| 2nd century AD |

Cohors prima Frixiavonum ("the first cohort of the Frisians ") |

The cohort had a strength of 500 men and was originally recruited from the Frisian tribe. Their settlement area extended over the Noordbrabant, a landscape in the Netherlands, south of the Meuse . The presence of the cohort in Brocolitia is known from an altar donated by an optio named Mausaeus after fulfilling a vow to the goddess Coventina. The unit was relocated to Rudchester ( Vindobala ) in the 3rd century . |

| 2nd century AD |

Cohors secundae Nerviorum ("the second cohort of the Nervii ") |

The troops were originally made up of recruits from the Nervier tribe in the Gallia Belgica province (now Belgium, Hainaut region). She arrived in Britain with the army of Quintus Petillius Cerialis in 71, along with five other Belgian cohorts. The unit is also mentioned on an undated building inscription from the warehouse at High Rochester ( Habitancum ), where it was assigned to the cohors IV Gallorum for construction work. The cohort also camped for some time in Fort Wallsend ( Segedunum ). The troops are named on an undated altar inscription dedicated to the genius of the camp. |

| 2nd century AD |

Cohors quintae Raetorum ("the fifth cohort of Raeter") |

The troops were recruited in the province of Raetia , which stretched across western Austria, south-eastern Germany and eastern Switzerland. This cohort is first mentioned for Britain on a military diploma of 122. The diploma enumerated all units of the Northern Army under the governor Aulus Platorius Nepos. The further activities of the Raeter are not known. An altarpiece dedicated to Coventina by a soldier named Publius testifies to the presence of this troop in Brocolitia . |

| 3rd to 5th century AD |

Cohors prima Batavorum ("the first cohort of the Batavians ") |

The soldiers of this troop originally came from the Lower Rhine. Their settlement area was around the current cities of Rotterdam , Sleidrecht , Geldermalsen and Tiel , all in what is now the Netherlands . In Britain it has been traceable since 122 AD. This cohort also had riders in its ranks ( cohors equitata ). The Batavians were considered to be specialists in river crossings in full armor. The earliest inscriptions date from the first quarter of the 3rd century. Ten inscriptions from Brocolitia are known that name this unit, they date between 213 and 237. Two gravestone inscriptions mention a horn player ( Bucinator ) and a standard bearer ( Signifer ) who had served in this cohort. One of their commanders, Domitius Cosconianus, donated an altar for Coventina around 140. From the Notitia dignitatum , troop list of the Dux Britanniarum , the rank of its commanding officer, a tribune , is known for the Procolitia of the 4th century . Since the troops appear in this late antique document, they could have stood here until the withdrawal of the Roman army from Hadrian's Wall. |

Vicus

The vicus is mentioned in several inscriptions from the 3rd and 4th centuries. The observations of John Horsley and Nick Hodgson could be confirmed by aerial photographs, which immediately in front of the fort showed clear traces of long rectangular building structures on both sides of the military road. The camp village, which was only very small in terms of area, spread over the low-lying, swampy terrain west of the fort. Today there are no noteworthy remains of it to be seen, as its buildings also fell victim to the centuries-old stone robbery. On the west side you can still see six terraces with embankments up to a height of 2.1 meters on the slope parallel to the fort. In the north half they overlay one of the camp trenches. The densest construction (remains of foundations and house platforms) could be observed on the west side, around 60 meters in front of the fort. The archaeologist Nick Hodgson also came across building traces in the south. 50 meters south-east of the Mithraeum ran a 3.5-meter-wide road, which was paved with large stone slabs, including gravestones that were used for a second time. Construction periods could not be determined. Some of the wall remains from the turn of the 3rd to the 4th century, as coins from the time of the emperors Claudius II and Tacitus were found on them.

Thermal bath

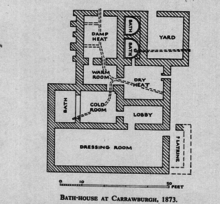

The bathhouse ( balnaeum ) examined by John Clayton (1792–1890) at the end of the 19th century stood in front of the west gate on the grounds of the vicus and consisted of seven rooms. It was a row-type bathroom - often found at Limes forts - with changing room, toilet, tepid, hot and cold bath and was similar in many details to the bathhouses of Benwell, Chesters and Netherby, but was much smaller. The thermal baths were last renovated in the 4th century. Its exact position is unknown today, a rise in the ground still recognizable on the west side of the fort seems to be the most likely location. From there, a paved road discovered in 1977 led to Maggie's Dene Burn.

Cult building

The remains of three Roman sanctuaries were discovered in the lowland marshes around the fort. The Mithraeum, the Coventina Spring and the Nymphaeum are on Maggie's Dene Burn, which flows into the South Tyne 1.8 km from Carrawburgh, near the Stanegate Fort of Newbrough . It is believed that Brocolitia was an important cult center on Hadrian's Wall.

Mithraeum

80 meters from the south-west corner of the fort, on the east bank of the stream, there was a temple for the god Mithras , who was especially worshiped by the Roman military . It was probably built around 200 by the soldiers stationed in the fort. The mithraea was completely exposed by IA Richmond and JP Gillam in the middle of the 20th century. After a period of drought, the tops of the three original altars and masonry protruded from the otherwise heavily boggy ground. The bases of the wattle wall between the anteroom and the cult room and those of the roof support beams were particularly well preserved. One of the roof beams could also be recovered from the rubble. The preserved masonry of the temple is still visible several layers of stone. The altars erected there today and the two reliefs of Cautes and Cautopates are casts of the Roman originals that are now in the collection of the Chesters Museum. The wooden pegs mark the position of the support beams. A small wrought-iron altar shovel from the 3rd century has also been preserved from the cult inventor. It is the only known Mithras shrine outside the Rhine provinces, in which a statue of the goddess Vagdavercustis was venerated, which stood to the right of the entrance.

The excavations revealed that the building went through three phases of construction:

- Phase I: The early temple was still relatively small, about 5.5 meters wide and eight meters long. The floor was made of tamped clay. As is usual with such temples, the interior should convey the atmosphere of a cave. In most cases it was divided into an anteroom and a cult room. In Brocolitia the vestibule and the cult room were separated by a wattle wall. In the anteroom, the archaeologists came across a fireplace where u. a. Pine cones had been burned. The cult meals were probably prepared here. A kind of sacrificial pit was set in the ground next to the fireplace. Pig, lamb and goat bones were found in it. On both sides of the cult room podium-like benches were set up, on which the believers sat during the rites. At the northern end there was a small gallery on which the altars were placed. They were donated by three prefects, all of whom were commanders of the cohors I Batavorum . They all came from the 3rd century. One could be dated between 213 and 222. Below the main altars was a sacrificial pit that contained a thin-walled bowl, a mug and poultry bones.

- Phase II: The Mithräum was later extended to eleven meters in length and a long rectangular niche to accommodate the Mithras relief. The cult room was again lavishly furnished and decorated and the roof supported with an extensive wooden structure. Dried heather was strewn on the floor. Temple II was forcibly destroyed in 296 or 297. Most of the stone monuments remained intact.

- Phase III: Shortly afterwards, the Mithraeum was rebuilt. After Constantius Chlorus put down the Carausius Rebellion , it was renovated for the last time. At the beginning of the fourth century it was destroyed again, possibly by Christian zealots. After that the place of worship should have been abandoned.

The Mithras relief - on which the tauroctony scene was depicted - and the Cautes / Cautopates reliefs were deliberately smashed according to the location of the find (see also iconoclasm ). Only a fragment of the Mithras relief could be recovered. Four smaller altars and the images of Cautes and Cautopates stood along the side benches. The left main altar bears a representation of Mithras, crowned by a halo that is lit from behind with a torch. Behind this stood the Mithras relief. The altars and other cult images are casts of the originals that are in the Newcastle Museum. The final coin on the site of the Mithräum was a freshly minted follis of Maximian (296–308). The complete lack of coins from the period after 308 suggests that the temple was no longer in use in the 4th century. A reconstruction of the sanctuary can be viewed at Newcastle University, Great North Museum.

Nymphaeum

At the end of the 1950s, another sanctuary was found on the south side or directly in front of the entrance to the Mithraum. It was the remains of a nymphaeum that was completely excavated by DJ Smith between 1957 and 1960. The nymphaeum was likely built during the third century and remained in use until the early fourth century. No remains of it are visible today. It consisted of a semicircular stone bench built into the slope with a paved floor. The spring water was collected in a low basin lined with stone slabs. The place of worship was probably not covered. It is very likely that the relief of the Carrawburgh triad of nymphs was originally placed here. One of the altars was carved from sandstone and bears the same inscription on the front and back. This indicates that he was standing in the center of the sanctuary. Two altar stones were dedicated to the nymphs, one donated by soldiers of the legio VI Victrix and the other by the Bataverkohort (for Coventina and the camp genius , genius loci ).

Coventina spring

This sanctuary of the Romano-British goddess Coventina is located west of the fort ("Coventinas Well"). Little of it is visible today, only a single standing stone marks the archaeological site. Apart from the source enclosure, there are still a few stones from the east and south walls. It was probably built between 128 and 133. Its remains (enclosing wall of the spring) were mentioned as early as 1732 by John Horsley and uncovered in 1876 by John Clayton. It was a simple square building measuring 12 × 12 meters, consisting of an enclosure wall and a basin, which was built around several springs emerging from the ground. The 5 meter wide entrance was on the west. Since no remains of roof tiles or wooden beams could be found, it is assumed that the building was not roofed. The 0.9 meter thick enclosure wall consisted of massive stone blocks. When it was discovered, it was still about three feet above the ground. The walls of the 2 meter deep and 2.6 × 2.4 meter large pool consisted of large, carefully hewn stone blocks. The bottom was covered with gravel. When the sanctuary was discovered, they were still preserved on 4 rows of stones above the waterline. On the north side, one of the blocks was carved out like a tub. The basin drain was also made of stone. The building structure was typical of Celto-Roman spring sanctuaries. In the interior and tw. In the spring basin there were 22 stone altars, which were originally probably all lined up on the walls. In addition to coins, John Clayton was able to recover a large number of other votive offerings from the spring basin. It was therefore not a healing cult that was practiced here, only the source was venerated. According to the coins found, the sanctuary was used until the end of the 4th century. Carrawburgh is the only Coventina shrine site identified in Great Britain to date. Two other possible sites are in France.

Burial ground

Soldiers and civilians from Brocolitia buried their dead in a cemetery on the east side of the fort. The first bones were found in 1807 between the camp and Mile Fort 31. Ten years later, Roman urn graves were found during earthworks in the east of the camp. A total of five headstones have been found at Carrawburgh, but their original locations are unknown. Archaeologists also found the remains of a small temple or tomb in 1964.

See also

literature

- John Clayton, Charles Roach Smith: The Temple of the Goddess Coventina. At Procolitia, Northumberland 1878. (English; paperback: Kessinger Publishing, 2010, ISBN 978-1-167-16901-4 )

- Guy de la Bédoyère : Hadrian's Wall: history and guide. Tempus, 1998, ISBN 0-7524-1407-0 .

- Peter Salway: The frontier people of Roman Britain. (= Cambridge classical studies ). Cambridge Univ. Press, 1965.

- John Collingwood-Bruce: Handbook to the Roman Wall. 12th edition. Newcastle-upon-Tyne 1966.

- Nick Hodgson: Hadrian's Wall 1999-2009. Titus Wilson & Son, Kendal 2009, ISBN 978-1-873124-48-2 .

- Hadrian's Wall Map and Guide. Ordnance Survey, Southampton 1989, OCLC 165461449 .

- Ronald Embleton, Frank Graham: Hadrian's Wall in the Days of the Romans. Newcastle 1984, pp. 117-121.

- Les Turnbull: Hadrian's Wall History Trails. Guidebook IV. Newcastle 1974, pp. 26-28.

- MJT Lewis: Temples in Roman Britain. Cambridge 1966.

- IA Richmond, JP Gillam: The Temple of Mithras at Carrawburgh. Archaeol. Aeliana. No. 4 XXIX, the excavation report 1951.

- Lindsay Allason-Jones, Bruce McKay: Coventina's Well. Oxbow Books, Oxford 1985.

- Lindsay Allason-Jones, Bruce McKay: Coventina's Well, a shrine on Hadrians Wall. Chester Museum, Oxford 1985.

- Eric Birley: Research on Hadrian's Wall. 1961, pp. 175-178.

- R. Blair: Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Newcastle upon Tyne. No. 10, 1901-1902.

- David J. Breeze 1972 Excavations at the Roman fort of Carrawburgh, 1967-1969, Archaeologia Aeliana or miscellaneous tracts relating to antiquity, Third series Volume 1 (1904) - 21 (1924) 50.

- Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Newcastle. (2nd Series) 10, 161.

- Journal of Roman Studies. 58, 1968, p. 179.

- RG Collingwood, RP Wright: The Roman Inscriptions of Britain. Clarendon Press, Oxford 1965.

- JH Corbitt: The Goddess Coventina and her Well at Carrawburgh. In: Northumberland Archeology News. 6 (5) 1958.

- Miranda Green: The Gods of the Celts. Bramley Books, Surrey 1986.

- Miranda Green: Celtic Goddesses, Virgins, Mothers. British Museum Press, London 1995.

- E. Huebner: The find of Procolitia. In: Hermes. Volume 12, Issue 3, Franz Steiner Verlag, 1877, pp. 257-271.

- Maarten Jozef Vermaseren : Corpus Inscriptionum et Monumentorum Religionis Mithriacae . 2 volumes. Martinus Nijhoff, The Hague 1956–1960.

Web links

- RIB Roman Inscriptions of Britain inscription database

- Hadrian's Wall photo album on Flickr

- Brocolitia on Roman Britain

- Carrawburgh / Brocolitia PASTSCAPE

- Satellite photo of the fort area, location of Roman monuments on Vici.org.

- Eric Edwards Collected Works: The Goddess Coventina of Northumbria

- Coventina's Well at Carrawburgh (Northumbria)

- Images of the finds from the Coventina spring

- The Carrawburgh Mithraeum, Britain, description and reconstruction (English)

- The wall from Arbeia to Maia. Film production with 3D-CGI models, images and explanations of the individual Roman castles along Hadrian's Wall, Part VI on You Tube, (English).

- Hadrian's Wall Camera, Page VIII, Brocolitia to Vercovicium, Milecastles 31 to 37, images and descriptions of places (English)

- The Megalith Portal, aerial view of the fort area

- John Collingwood Bruce: The Roman Wall: A Description of the Mural Barrier of the North of England, 1867, with numerous pictures of wall remains, altars, inscriptions etc.

Remarks

- RIB = Roman inscriptions in Britain

- ↑ Gaelic : broc, bruic = badger, toll, tuill = hole, Welsh: broch = badger, twll, tyllu = hole, RC 148, ALF Rivet, Colin Smith 1979, pp. 431–433, Guy de la Bedoyere, 1998, P. 65, JC Bruce 1966, p. 100.

- ↑ Guy de la Bedoyere 1997, E. Hübner 1877, p. 17.

- ↑ E. Hübner 1877, p. 17, Lindsay Allason-Jones / Bruce McKay 1985, Coventina's Well: a shrine on Hadrian's Wall.

- ↑ Eric Birley 1961, pp. 175–178, R. Blair 1901–1902, pp. 161–164, David J. Breeze 1972, pp. 81–144, Guy de la Bedoyere 1998, p. 67, JC Bruce 1966, P. 102.

- ↑ JC Bruce 1966, p. 101.

- ^ Society for Promotion of Roman Studies. The journal of Roman studies No. 58, 1968, p. 179.

- ↑ JC Bruce, 1966, p. 100.

- ^ Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies Britannia: a journal of Romano-British and kindred studies, No. 1, 1970, p. 276, JC Bruce 1966, p. 101.

- ↑ JC Bruce 1966, p. 100.

- ↑ RIB 1547 , RIB 1554 , RIB 1555 , RIB 1556

- ↑ RIB 1550 ; Hadrian ?, Brough on Noe: RIB 283 ; 158 AD, Bakewell: RIB 278 ; Altar, Corbitt 1958.

- ↑ RIB 1563b ; JRS lvi (1966), p. 218, No. 5, Castlecary: RIB 2155 139-161, Cramond: RIB 2135 altar inscription, Housesteads: RIB 1578-1580 , 1584-1586 , RIB 1591 , RIB 1598 , altars; RIB 1618/1619 tombstones; RIB 1631b 205-208.

- ^ RIB 1524 , Newbridge near Cramond: RIB 2313 , milestone, set 140-144.

- ↑ RIB 1523

- ↑ RIB 1538

- ↑ RIB 1529 ; Altar stone

- ^ ND Occ. XL, 23, RIB 1544 , RIB 1545 .

- ↑ Peter Salway 1965, pp. 81–83, Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies Britannia: a journal of Romano-British and kindred studies. No. 9, 1978, p. 420, JC Bruce 1966, p. 101.

- ↑ MJ Vermaseren: Corpus Inscriptionum et Monumentorum Religionis Mithriacae, Volume I, The Hague 1956, Nijhoff, Manfred Clauss: Cultores Mithrae, Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart 1992, Guy de la Bedoyere 1998, pp. 68-69, IA Richmond / JP Gillam, 1951, p. 1ff.

- ↑ RIB 1547

- ↑ Guy de la Bedoyere 1998, pp. 66-67, Allason-Jones / McKay 1985, pp. 6-11 and 19-50; Allason-Jones, 1996, pp. 115-118.

- ↑ EC Waight: Ordnance Survey Archeology Division Field Investigation 1966, An archaeological watching brief in association with a coring survey along the B6318 'Military Road', Throckley-Gilsland, Tynedale, Northumberland 2007.