Habitancum

| Risingham Castle | |

|---|---|

| Alternative name |

a) Habitancum b) Habitanci |

| limes | Britain |

| section | Line 2 (outpost) |

| Dating (occupancy) |

Antonine / Severan , 2nd to 4th century AD? |

| Type |

a) cavalry fort, b) cohort fort, c) street fort |

| unit |

a) Legio VI Victrix (Bauvexillation), b) Cohors IIII Gallorum , c) Cohors I Vangionum , d) Numerus Exploratorum Habitancensium , e) Cohors II Nerviorum , f) Raeti Gaesati |

| size | Area: 1.6 ha |

| Construction |

a) wood and earth fort, b) stone fort |

| State of preservation | Square floor plan with rounded corners, visible above ground (fort platform and wall at the NE corner) |

| place | Corenside |

| Geographical location | 55 ° 10 '12 " N , 2 ° 10' 19.2" W |

| Subsequently | Bremenium Fort (outpost, north) |

| Upstream | Fort Onnum (wall fort , south) |

Habitancum was a Roman auxiliary fort in the parish of Corsenside / Hamlet Risingham, County Northumberland , England .

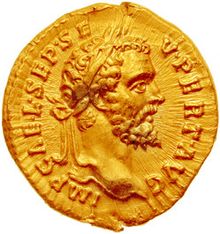

It was part of the ramp protection of Hadrian's Wall, which consisted of a total of four forts, and stood on a Roman highway that led far to the north of Caledonia . The fort probably also played an important role as a starting point and retreat base during campaigns by the Roman army in the north. The early wood and earth fort was built under Emperor Antoninus Pius and destroyed in the late 2nd century. Rebuilt in stone during the reign of Septimius Severus , it burned down again in the late 3rd century. Repaired again in the early 4th century, it was finally devastated at the end of the century and abandoned by the Romans. The camp almost certainly included a larger civil settlement and a burial ground. Its area probably still contains numerous important archaeological finds for future excavations, which will offer new insights into life on the outermost edge of Roman Britain.

Surname

The fort is mentioned in three ancient written sources. One is a consecration altar that was found in the Rede River and donated by a beneficiary ( Habitanci ). On a consecration altar, dedicated to the imperial couple Septimius Severus and Julia Domna and the spirits of their ancestors, the place is called Habitancum . It is also listed in the Ravenna cosmography of the geographer of Ravenna (7th century), also as Habitancum . The etymology of the Latin place name is uncertain. It seems to consist of two parts: the Roman name habitus, the meaning of which is unclear, but possibly goes back to a clan head or a landowner or even stands for a whole group (like the Anglo-Saxon ingas , 'people'). The cognomen is Avitus, along with many derived forms (Abitus, Avithus, Avittus). The final syllable -ium is a Latin suffix that denotes property. The place name could therefore be interpreted as “the place of the people of habit”. Ie the fortress was perhaps built on land that could originally have been owned by a Romano-British. Roman fortresses were usually not named after their builders or first commanders.

location

The fort is 21 km north of Corbridge ( Coriosopitum / Coria ) and 13 km south of High Rochester ( Bremenium ), the nearest Roman fortress on Dere Street , which led to Melrose ( Trimontium ) and the Antonine Wall . The area is located in a northern depression between the hills near the south bank of the Rede, in a field west of the present-day A68 between Corbridge and Jedburgh, about 800 meters from the hamlet of Woodburn, near the point where the A68 road crosses the river at the entrance to the town from the west Woodburn crosses, and is one of the grazing grounds of Broadgate Farm. In the southwest, the Chesterhope Burn flows past the camp and flows directly northwest into the Rede. There the route of the ancient Dere-Street deviates from the A68 in the west and joins the A68 again after about 3 km in the north. The fort area is now almost 200 meters from the banks of the Rede, as its course has now shifted further to the northwest. In Roman times it was only about 45 meters. The river probably also served as a transport route with which the fort could be supplied with supplies from the Corbridge warehouses by flat-bottomed freighters. So far no traces of a Roman bridge have been discovered. Dere Street connected the fort to the north with the camps in High Rochester ( Bremenium ), to the south with Halton Chesters ( Onnum ), the wall passage at Portgate and the Coriosopitum supply center.

Research history

Many Roman finds made in Risingham were first brought to Conington by Robert Bruce Cotton in the 17th century and later bequeathed to Jesus College in Cambridge. Parts of the fort were exposed during the 19th and 20th centuries. During investigations between 1839 and 1842 Richard Shanks discovered the remains of the fort bath at the southeast corner and that of the camp headquarters in the center of the fortress. A building inscription was excavated near the bathing building in 1844 and signed by John Bell. The original has since been lost. The camp headquarters was exposed during excavations in 1840, 1849 (Robson) and 1935. The building inscription from the stone construction phase from the year 213 was recovered. John Kenneth Sinclair St. Joseph made aerial photographs of the fort area in the 1960s. During construction work in 2004, a fragment of Roman ceramics (so-called Black Coarse ware) was found. Between 2009 and 2012, geophysical investigations took place on the fort area and revealed a dense building structure. In addition, aerial photographs of the square were taken again. Since the fort area was never built over in a modern way, a larger archaeological excavation should uncover a wealth of knowledge about this ground monument.

Find spectrum

Numerous Roman inscriptions (eighteen altars and seven dedicatory inscriptions) are known from Risingham and its vicinity. The ancient place name is given on two of them; An undated altar for the god Mogon and a dedication that was made at the beginning of the third century. Five altars were u. a. dedicated to the supreme state god, Iupiter Optimus Maximus . Two to Iupiter Dolichenus , three to Fortuna , three to Hercules , two to Mars , two to Mogon and an altar each for Diana , Cocidius , a local deity, the mother goddesses, the nymphs and the genius of the reigning emperor. During the excavations in 1840, a small hoard find consisting of 15 coins was found in the bathhouse, dating from the time of Gallienus (254) to Claudius Gothicus (269).

Robin of Risingham

One of the most remarkable ancient artifacts in the area around the fort is an ancient, approximately 1.2 meter high sandstone relief, popularly known as the "Robin of Risingham" or "Robin of Redesdale". Either it is a representation of a locally revered god of hunting, that of the Roman god of the forest, Silvanus , or the Celtic god Cocidius . The deity is probably standing next to an altar, wearing a belted tunic and a quiver with arrows on his back, and a cloak draped over his right and left shoulders. He holds a bow over his head in his left hand and a small animal sits in his right hand. First described by John Horsley in the 18th century, it is the only known Roman-era sculpture in Northumberland that was carved out of a rock. In the 18th century, the then landowner blasted the upper part of the relief with gunpowder out of anger at the large number of visitors. The underside with the legs of the figure are all that is left of the original sculpture today. In 1983 the Redesdale Society erected a replica of the destroyed upper part in front of the antique original.

development

In 122 the Emperor Hadrian ordered a barrier wall to be built in northern Britain, reinforced by watchtowers and forts, from the Tyne to the Solway Firth, to protect the British provinces from the constant incursions of the Picts from the north. Most of the wall was built by soldiers from the three legions stationed in Britain and the Classis Britannica . Five forts (two of which were supposed to secure the tribal area of the allied brigands ) were located in the vicinity north of Hadrian's Wall. The tasks of the crews initially included securing and monitoring the main traffic routes.

The initial phase of the Roman occupation of Risingham is still largely hidden in the dark of history; to this day no evidence has emerged that the fort was built at the same time as Hadrian's Wall. A first fortification (wood-earth fort) was built by a building vexillation of the Legio VI - only between 139 and 140 - under Emperor Antoninus Pius , as a related building inscription suggests. However, it has not yet been possible to precisely date it. During the excavations, ceramic shards from the early second century were found on the western wall. It was probably used to secure the occupation of the Central Lowlands up to the Antonine Wall . The wall and a gate were renovated in the 2nd century. It is believed to have burned down as early as the end of the 2nd century (approx. 197) during an invasion of the northern tribes and then temporarily abandoned by its occupation. It could also have been a planned evacuation and destruction of the site by the army.

Under Septimius Severus the region was pacified again, the fort was occupied with a Vangion cohort and completely rebuilt in stone. This was probably in the course of the large-scale repair work on the infrastructure of Hadrian's Wall between 205 and 208, in preparation for a campaign by the emperor and his two sons to the north. From the reign of Caracalla , the fortress served as an outpost. Until the middle of the 3rd century, Habitancum and the neighboring Bremenium were also occupied with reconnaissance ( exploratores ), which suggests increasingly troubled times. Habitancum was destroyed again in the late 3rd century (presumably in a concerted attack by the Caledons and Maeter in 296 after the defeat of Allectus ). A thick layer of fire over the floors of the Severan buildings suggests that Habitancum was overrun at that time. In the early 4th century, around 306, it was rebuilt. The camp was again destroyed - probably towards the end of the 4th century (according to the findings, between 367 and 369) and then finally abandoned. This could have happened in the course of the retreat of the army behind Hadrian's Wall, which perhaps began as early as 312 (under Constantine I). Perhaps as a concession for a peace treaty made with the northern tribes. The Roman high command should finally have come to the conclusion that the benefit of a military presence so far north of the wall was disproportionate to the expenditure of material and soldiers required for it. By the end of this century at the latest, the other outpost forts had also been closed.

In the Middle Ages, a settlement was founded in the castle ruins. The camp was probably largely destroyed by stone robbery during this time. Another settlement at Risingham is mentioned in 1604 by a certain Elizabeth Swan. Its last known resident emigrated in 1826.

Fort

Habitancum went through four construction phases during its useful life.

The only remains of the first, Antonine, phase found so far are a layer of ash and charred wooden beams from the 2nd century under the western wall of the stone fort. Their garrison force, the Cohors IV Gallorum , comprised around 500 men. From this one concludes that the wood and earth fort must have covered an area of approximately 1.21 hectares.

The Severan stone fort did not stand exactly above the foundation walls of the Antonine wood-earth camp and faced west. The only remnants still visible above ground today are two rows of stones of the rising (inner height of 0.5–1.2 meters, outer height of 2.5–3.5 meters) at the NE corner and some sections of the weir ditches that are still are visible on three sides (west, south and east). They date from the early 3rd century. The northwestern part of the north wall was washed away by the Rede. The fort had a long rectangular floor plan with rounded corners, was oriented to the northwest and measured 135 meters from north to south, 117 meters from east to west and covered an area of almost 1.6 hectares. It was surrounded by a total of four trenches. They are still clearly visible on the west and south sides, but have been mutilated by agricultural activities. The fort wall consisted of an earth and quarry stone core, faced with carefully hewn sandstone blocks, which was reinforced at the rear by a ramp made of mud (width 9-10 meters). It also served as a battlement. In places it has been preserved up to a height of 1.2 meters. The wall base consisted of sandstone blocks cut diagonally at the front.

Gates and towers

The north, south and west gates have been archaeologically proven. Their locations can be recognized by 8 meter wide gaps in the wall. The location of the east gate has not yet been localized. The ditches were bridged with earth dams. A gap in the middle of the northern wall should mark the location of the north gate. Such gates were usually flanked by two towers. Slight elevations in the ground on both sides of the west and south gates mark the position of the gate towers. The former served as the main gate ( porta praetoria ), but had only one passage. The flank towers protruding from the wall looked more like specimens of late Roman military architecture. The eastern flank tower may have collapsed once and was then rebuilt. The passage was later narrowed even further so that it was only passable for pedestrians. From the west gate, which was last renovated in the 4th century, a road led across Chesterhope Burn to Dere Street.

The corners of the fort were secured by rectangular towers attached to the inside. Today only grassy hills can be seen of them. The northwest corner tower was destroyed by changing the course of the Rede. The walls were additionally reinforced by rectangular, internally attached intermediate towers. You can still see slight elevations from them.

Interior development

Only a few details of the interior are known. The outlines of some of the buildings are still clearly visible on the lawn inside the warehouse. The most recent interpretation of these remains has shown that the majority of the fortress probably came from a post-Roman period of use. However, the dating is uncertain. In addition to the camp headquarters ( principia ) in the center and the bathing building ( therme ) in the SE corner, the fort certainly had the other buildings that were standard for mid-imperial camps: one or two granaries ( horrea ), horse stables ( stabula ), probably up to 18 crew barracks ( centuria ) and workshops ( fabricae ).

There are no more surface traces of the bathhouse in the southeast corner of the fortress. The only recognizable remains of Roman buildings are those of the Principia. These consist of a mutilated wall, a remnant of the northern end of the transverse hall ( basilica ). It had a dais with three steps leading up to it. There is also a deepening in the ground at the flag sanctuary ( Sacellum ) and a pivot stone at the entrance. The principia of the stone fort was built (according to the building inscription recovered in 1849) around 213 and is likely to have burned down at least once after that, probably around 343. Then it was rebuilt and used for a longer time, as induced by strong signs of wear on the floors and the door sills. Because of the fort's exposed location, the bathing building was also within the walls, despite the high risk of fire. It was probably destroyed in the late 3rd century, but renovated again under Constantine I between 305 and 306. Numerous reused stone fragments ( Spolia ) were discovered in its walls . In the vicinity of the central interval tower on the east side of the camp there is still a roughly worked stone on which two small square indentations have been carved, possibly pivot or dowel holes.

garrison

Habitancum was presumably occupied by regular Roman soldiers from the 2nd to the late 4th century. During its existence it housed several cohorts of auxiliary troops ( auxilia ). It is not yet known which unit was stationed there first. The name of a field signer , Julius Victor, is known from his gravestone. However, its unit was not specified on it. The governor set up a kind of street police to collect taxes and to control the movement of goods on Dere Street . For one of them, Marcus Gavius Secundinus, Habitancum was his first place of employment ( prima statione ) in the office of beneficiarius consularis, according to an altar inscription .

The following units either provided the fort's crew or may have stayed there for a limited time:

| Time position | Troop name | description |

|---|---|---|

| 2nd century AD |

Legio sextae Victrix ("the sixth legion, the victorious") |

Legionaries were usually not assigned to garrison service on the border, but sent special forces for the more demanding construction projects on Hadrian's Wall. The presence of members (construction crew) of this legion is confirmed by a building inscription discovered in 1844 near the fort bath. The Legion's headquarters were in Eburacum (York). |

| 2nd century AD |

Cohors quartae Gallorum quingenaria equitata (the fourth cohort of the Gauls, 500 strong, partly mounted). |

This partially mounted unit was in Habitancum and Bremenium at the time of Marc Aurel (161-180) and was originally recruited from tribes in the Gallic provinces in what is now France. The cohort is known on several inscriptions from Vindolanda (Chesterholm) at Stanegate , as well as from the third and fourth centuries. It also appears in the Notitia Dignitatum ; The unit is believed to have been located in Risingham from the third century onwards. The troop is further mentioned on two undated gravestones from Templeborough (South Yorkshire), which must have been their former garrison location, and on a couple of - also undated - consecration altars from Camboglanna (Castlesteads) on Hadrian's Wall. In the case of Risingham, the unity is mentioned on another undated inscription dedicated to the deified emperor (altar?) And a tombstone. |

| 2nd century AD |

Cohors secundae Nerviorum (the second cohort of the Nervier) |

This unit of the Gallic Nervians is only mentioned on a single - badly damaged - inscription from Risingham. It was previously in the ramparts Segedunum (Wallsend), Brocolitia (Carrawburgh) and in Vindolanda (Chesterholm) on Stanegate . |

| 3rd century AD |

Cohors primae Vangionum milliaria equitata (the first cohort of Vangions , partly mounted, 1000 men strong) |

The Vangionen settled on the west bank of the Upper Rhine , around today's city of Worms and in the area between the Moselle and the Saar. This unit is mentioned on a total of twelve inscription stones from Habitancum . Some could be dated between 205 and 217. According to a building inscription from the south gate, it was built by this unit between 205 and 207. The cohort may originally have consisted of a thousand men. It is possible that at the time of Hadrian it was divided into two vexillations of 500 men ( quingenary ). The ramparts of Chesters ( Cilurnum ) and Benwell ( Condercum ) are attested as further of their stationing places on the northern border . The force was apparently reunited at Risingham around the middle of the third century. The names and rank of some of their commanders are known from the inscriptions found there. Including those of the tribunes Lucius Aemilius Salvianus , Iulius Victor and Aemilius Aemilianus . |

| 3rd century AD |

Numerus Exploratorum Habitancensium or Exploratores Habitancenses (a group of scouts in Habitancum) |

This unit is mentioned in three inscriptions. One of them, a building inscription, could be dated to the year 209. Accordingly, their soldiers, together with members of the Vangionen cohort and the Raeti Gaesati , built the south gate. They were moved to Habitancum in the course of the Caledonian campaigns of Septimius Severus . According to an inscription from the neighboring fortress of Bremenium (High Rochester), a vexillation of this unit was also stationed there. In the Notitia Dignitatum , two more explorer units appear, in Lavatris (Bowes) and on the Saxon coast , Fort Portus Adurni (Portchester). |

| 3rd century AD |

Raeti Gaesati (Rhaetian spear throwers) |

These soldiers were originally recruited in the province of Raetia (today Bavaria, Switzerland and Austria) and were among others. a. armed with javelins. Her presence in Risingham is attested by several altar stones and an inscription from the Principia (with a dedication to Caracalla and his mother Julia Domna ). One of them was donated together with the Vangionen cohort. Another fragment of the inscription, presumably once part of an altar, was found above a door of Jedburgh Abbey, only a few kilometers from Risingham. The stone was probably carried there from the fort. The name and rank of one of their commanding officers, the Tribune Julius Severinus, are also known from him. |

Marching camp

There were also three temporary marching camps in the vicinity of Risingham, two of them at Swine Hill / Four Laws.

| place | description |

|---|---|

| Swine Hill I. | The fortification was directly on Dere Street, about 60 meters west of the present-day Motorway (Dere Street) and 4 km southeast of Risingham Fort. The earlier (larger) of the two camps had a square floor plan, measuring around 168 meters (east-west) × 174 meters (north-south), thus covering an area of 2.4 hectares and superimposing the route of Dere Street in the east. The north wall is still up to a height of 0.5 to 0.9 meters high. The depth of the outer moat varies between 0.2 and 0.4 meters. Most of the east wall is up to 0.9 meters high. The trench on this side is still 0.2 or 0.4 meters deep. The south wall is best preserved and in some places still reaches a maximum height of 1.1 meters. The trench is up to 0.4 meters deep here. The western wall, however, is only 0.5 meters high. There is nothing to be seen of the ditch there. In several places on the north, south and east sides small bulges can be seen on the inner edge of the earth ramp, probably a kind of platform. They measure 2.5 meters in diameter and are still up to 0.4 meters high. Seven of them are located south of the east gate. What they were used for is still unclear. The fort had three gates, which were secured by an earth rampart (so-called clavicula ). Such camp entrances could be proven from the reign of Vespasian (69 to 79 AD). An extension of the camp wall was arched around the gate entrance in order to prevent attackers from penetrating directly into the interior of the camp. The passage was additionally blocked and closely guarded by a number of tribuli , wooden Spanish horsemen . They were centrally located on the east, north and south sides. None could be detected in the west. They are also extremely well preserved; The earthwork of the north and south gates is still up to a height of 0.8 meters. That of the east gate still reaches a height of 0.7 meters. |

| Swine Hill II | The second camp had been installed in the northeast corner of Swin Hill I. The defensive walls of the previous building were reused in the north and east. The walls were, however, much weaker and some of them are still up to 0.4 meters high. The dimensions of this camp were about 60 × 60 meters, it thus covered an area of 0.3 hectares. On Dere Street there was also a Roman milestone from the 4th century, from the reign of Galerius (305-311), south of the Marching camp at Waterfalls, discovered. It had only two gates, they both broke through the eastern wall and were designed as so-called Titulum gates. Characteristic for such gates is an additionally raised earth wall with a pointed ditch (still 0.3 meters deep) in front of the entrance. The south gate is best preserved. Its earthwork reaches a height of 0.4 meters, the trench in front of it is still 0.2 meters deep. There appear to have been no gates on the other sides of the fortification. |

| West Woodburn | This marching camp was 1.6 km northeast of the fort in a field near West Woodburn in the Redesdale valley. The Rede River flows around it on three sides. Only the course of the north, west and east sides, together with the north-east, south-east and north-west corners could be proven. The south-western part of the camp was destroyed by centuries of agricultural use of the area. The camp presumably covered an area of 11 hectares. It is believed that around three thousand men were housed there. It also appears to have a standard square floor plan with rounded corners (playing card shape). It could be entered through two gates, centrally located on the north and east wall and made in the titulum construction. The best preserved northern section has a length of about 6.7 meters. |

Vicus and burial ground

The existence of a civil settlement and a burial ground outside the fort is confirmed by the discovery of seven gravestones. They were set for civilians and soldiers. The settlement probably surrounded the camp in the west, east and south, but has not yet been explored.

See also

literature

- John Hodgson: A History of Northumberland: The topography and local antiquities, arranged in parishes. E. Walker 1827.

- John Collingwood Bruce: Roman Wall. Harold Hill & Son, 1863, ISBN 0-900463-32-5 .

- John Collingwood Bruce: Lapidarium Septentrionale, or A Description of the Monuments of Roman Rule in the North of England. B. Quaritch, Newcastle upon Tyne, 1870-1875.

- Frank Graham: The Roman Wall, Comprehensive History and Guide. Frank Graham 1979, ISBN 0-85983-140-X .

- Chris Scarre: Chronicle of the Roman Emperors. Thames & Hudson, London, 1995.

- Albert Rivet, Colin Smith: Place Names of Roman Britain. Batsford, London, 1979.

- RG Collingwood, RP Wright: The Roman Inscriptions of Britain. Vol 1, Inscriptions on Stone, Oxford 1965.

- Shepard Frere, John K. St Joseph: Roman Britain from the Air, 1983.

- Anne Johnson: Roman Forts. 1983, p. 287.

- Ian Alexander Richmond: Northumberland County History, XV, therein The Romans in Redesdale, 1940.

- IA Richmond: Archaeologia Aeliana: or miscellaneous tracts relating to antiquity. No. 13, 1936.

- Humphrey Welfare, Vivien Swan: Roman camps in England: the field archeology. 1995.

- AJ Berggren: Ptolemy's Geography. Princeton University Press, 2000.

- David J. Breeze: Roman Forts in Britain. Shire Archeology, Oxford 2002.

- David J. Breeze: The Frontiers of Imperial Rome. Pen and Sword Books Ltd, Barnsley 2011.

- Duncan Campbell: Roman Auxiliary Forts 27BC-AD378. Osprey, Oxford 2009.

- H. Davies: Roman Roads in Britain. Shire Archeology, Oxford 2008.

- Nick Fields: Rome's Northern Frontier AD 70-235. Osprey, Oxford 2005.

- R. Hobbs, R. Jackson: Roman Britain. British Museum Company Ltd., London 2010.

- J. Waite: To Rule Britannia. The History Press, Stroud 2011.

- Guy de la Bédoyère: Hadrian's Wall: history and guide, Tempus, 1998, ISBN 0-7524-1407-0 .

- Jann Le Bohec: The Roman Army. Nikol 2009, ISBN 978-3-86820-022-5 .

- Kate Gilliver: On the Road to Empire. The history of the Roman army. Nicholas 2007.

- Nic Fields: Hadrian's Wall AD 122-410. Osprey, Oxford 2003, ISBN 1-84176-430-2 .

- Eric Birley: Research on Hadrian's Wall. 1961.

- John K. St. Joseph: Journal of Roman Studys, No. 59, 1969.

- Margot Klee: Borders of the Empire, Life on the Roman Limes. Konrad Theiss Verlag, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 3-8062-2015-8 .

- Marcus Reuter: Studies on the numbers of the Roman Army in the Middle Imperial Era, Dissertation, In: Reports of the Roman-Germanic Commission 80, 1999, pp. 359-569.

Remarks

- RIB = Roman inscriptions in Britain

- ↑ RIB 1225 , RIB 1235 , R&C No. 184, Rivet / Smith, pp. 361-362

- ↑ Frere / St.Joseph 1983, pp. 119 and 121.

- ↑ RIB 1208 , RIB 1209 , RIB 1212 , RIB 1215 , RIB 1221 , RIB 1224 , RIB 1225 , RIB 1228 , The Gentleman's Magazine, Volumes 169–170, F. Jeffries 1841, p. 135, Lapidarium Septentrionale, p. 329, John Hodgson 1827, p. 166.

- ↑ RIB 1239 RIB 1241 , Archaeologia Aeliana: or miscellaneous tracts relating to antiquity, No. 13, pp. 182-183 and 186-195, Bedoyere 1998, p. 120, Richmond 1936, pp. 184-198; id., “The Romans in Redesdale,” Northumberland County History XV, 1940, Birley 1961, pp. 235-240, St. Joseph, JRS 59, 1969, Margot Klee, 2006, p. 31.

- ↑ Archaeologia Aeliana, No. 13, pp. 182-183, pp. 186-195, RIB 1235 .

- ↑ RIB 1247 , RIB 1225

- ^ RIB 1239

- ↑ Nic Fields 2003, p. 47, RIB 1227 Altar? , RIB 1249 tombstone

- ↑ RIB 1303 , RIB 1538

- ↑ Bedoyere 1998, p. 20, RIB 1215 RIB 1216 Altar ?, RIB 1217 , RIB 1230 , RIB 1231 , RIB 1234 (205–208), RIB 1235 (209–213), RIB 1241 , RIB 1242 , RIB 1243 , RIB 1261a

- ↑ According to Marcus Reuter, the geographical surname Habitancensium or Habitancenses was subsequently added, as it has not yet been found in any inscription assigned to this unit. According to Reuter, in this case it is probably not a question of local, indigenous scouts, but of regular soldiers of the Roman army who were specially assigned for reconnaissance purposes. RIB 1235 , RIB 1243 , RIB 1262 (238-244).

- ↑ RIB 2117 , RIB 2118

- ↑ Welfare / Swan 1995, pp. 130-131.

- ↑ RIB 2293 (305-311), Welfare / Swan 1995, pp. 130-131.

- ↑ Jann Le Bohec 2009, Fig.25b, Kate Gilliver p. 93, Welfare / Swan 1995, p. 133.

- ↑ RIB 1246 , RIB 1247 , RIB 1248 , RIB 1249 , RIB 1250 , RIB 1251 , RIB 1254

Web links

- Roman Inscriptions of Britain (English)

- Habitancum on ROMAN BRITAIN

- Risingham on Castles Forts Battles

- Habitancum Castle on PASTSCAPE

- Habitancum Castle on HISTORIC ENGLAND

- Risingham Roman Fort (Habitancum)

- ADS: Habitancum Roman fort and medieval settlement

- Location Habitancum on Vici.org.

- Aerial view of the fort area

- Naming

- Keys to Past: Info Robin of Risingham