Castra Exploratorum

| Netherby Castle | |

|---|---|

| Alternative name |

a) Castra Exploratorum b) Axelodunum? |

| limes | Britain |

| section | Line 2 (outpost) |

| Dating (occupancy) |

Flavian / Hadrianic 1st to 4th century AD? |

| Type |

a) Cavalry fort b) Cohort fort c) Street fort |

| unit |

a) Legio XX (Bauvexillation) b) Legio VI Victrix (Bauvexillation) c) Legio XX Valeria Victrix (Bauvexillation) d) Cohors I Nervana e) Cohors I Aelia Hispanorum f) Numerus Exploratorum ? |

| size | unknown |

| Construction |

a) Wood and earth fort. b) Stone fort |

| place | Arthuret / Netherby Hall |

| Geographical location | 55 ° 2 '9.6 " N , 2 ° 56' 42" W |

| Previous | Uxelodunum Fort (southeast) |

| Subsequently | Blatobulgium Fort (northwest) |

Castra Exploratorum was a Roman auxiliary forces fort on the territory of the municipality ( Parish ) Arthuret, Carlisle District, the district Netherby, County ( County ) Cumbria , England.

Founded in the late 1st century AD and renovated in stone in the 2nd century, it was one of the forts used to secure Hadrian's Wall. Remnants of the fort are no longer visible, as they are now completely covered by the buildings and gardens of an aristocratic residence, Netherby Hall. It was probably occupied by Roman soldiers until the 3rd or 4th century AD at the latest. Its area has never been scientifically investigated. The existence of the fort is only known from earlier descriptions of its remains by scholars in the 16th century and from numerous Roman inscriptions found on site. Presumably there was also a larger camp village with a harbor on the banks of the Esk. Netherby Hall now houses a rich collection of Roman artefacts.

Surname

The ancient place name is only mentioned in the Antonini Itinerarium (early 3rd century). It comes from Latin , means "camp or fortress of the scouts" and in this form is so far unique in British toponymy . " Castra " is usually found in place names of the provinces of the Roman Empire further south. The term was also adopted into Anglo-Saxon. Perhaps from the Saxons on the continent or from mercenaries who served in Britain's provincial army in the late 4th century. There it is - depending on the dialect in several modifications - part of the place names of a number of former Roman cities, settlements or fortresses, such as B. Chester, Caster-Caistor, -cester, -xeter etc. The place is also known as Brocara . He has been handed down from one entry in the Ravenna Cosmography and found there between Fanocodi (Bewcastle) and the not yet localized Croucingo . For a long time it was assumed that the civil settlement of Castra Exploratorum was meant. However, there is no archaeological or written evidence to support this thesis. Brocara is now more equated with the fort of Brougham (Cumbria), which is also known under the name Brocavum . A fortress called Axelodunum also appears in the Notitia Dignitatum . It is commonly equated with Stanwix Castle . The Cohors I Aelia Hispanorum is said to have been stationed in this fort in late antiquity , but there is also evidence of Netherby. In light of this, it seems possible that the ND entry for Castra Exploratorum has been merged into Axelodunum (perhaps due to a transcription error) .

location

Athuret is on the River Esk and the North British Railway, near the border with Scotland. The village is 10 miles north of Carlisle and 2 miles from Longtown. The exact location, size and orientation of the fort are uncertain. In ancient times there were probably road connections to Blatobulgium (Birrens) in the north-west, to the fort of Broomholm, Hadrian's Wall / Uxelodunum (Stanwix), Luguvalium (Carlisle) and to Stanegate (Brampton / Old Church). In the Itinerarium , Castra Exploratorium is located at the beginning of Iter (Route) II , between Blatobulgium , the northern end point of this route and Luguvalium . According to this, it was 12 Roman miles each from Blatobulgium and Luguvalium . Although this does not exactly match the actual distances, it could be that the Roman road turned southeast to Brampton / Old Church in order to avoid the impassable coastal marshes at the mouth of the Solway Firth . This entry describes the route from Hadrian's Wall to what is now Richborough in Kent . Blatobulgio appears to be the northern terminus, about 12 Roman miles from Castra Exploratorum .

Research history and range of finds

The first reports of Roman wall remains in Netherby come from John Leland , who visited the place in 1539. He wrote:

“There were once many wonderful buildings here, as you can see from the destroyed walls. Some also claim to have seen retaining rings and jetties for ships here. The country is controversial, it is both English and Scottish. The ruins are now about three miles from the water of the Solway. Grass grows on the ruined walls. "

The first edition of William Camden's "Britannia" - from the year 1586 - speaks of "... wonderful and great ruins of an old city" at Netherby. In the 17th century, William Stukeley was of the opinion that the mansion stood exactly above the remains of the Roman fortress. He and two other scholars, Gale and Goodman, also came across the remains of the civil settlement and several roads that are said to have stretched northwest of the fort and along the riverbank. Stukeley also reports of a cemetery on a hill a bit away from the manor house, but he does not say which side of the house this hill is said to have been on. In 1601 , while visiting Netherby , Reginald Bainbrigg, a schoolmaster at Appleby , drew a Roman inscription which was walled into the front of a house. He also reported about iron rings that had been found there. In 1671 Sir Daniel Fleming mentions an "... amazing collection of (Roman) ruins " on the river bank. That was the last written mention in this connection until the bathhouse was found. In 1732, workers who were digging for stones that could be used for building purposes came across the remains of a Roman thermal bath that had stood on the area between the fort and the bank of the Esk. An inscribed altar was recovered from one of the rooms. 18 more Roman inscriptions later came to light. Some were dedicated to the gods of classical Roman mythology: Apollo, the goddess Fortuna, Silvanus, Mars and Jupiter the supreme god in the Roman pantheon. Almost half were set for Germanic gods: Cocidius, Huetirus, Moguntus and Belatucader. An altar was dedicated to an unknown deity and was severely damaged when it was found. A very beautiful sculpture, also found in Netherby, depicts a young man. He is standing in a niche with a wall crown on his head, in his left hand he holds a cornucopia and a patera with which he offers a libation on an altar ; It is one of the most beautiful stone works found on Hadrian's Wall. From the grooves carved in the lower part of the stone, one can conclude that the relief was originally set in masonry. Maybe to decorate the entrance of a temple with it. Gordon assumed it was dedicated to Hadrian; Lysons believed that it shows the " genius of the wall of Severus". John Collingwood Bruce believed that he represented the genius of the wall. Extensive archaeological studies are planned around Netherby Hall in the near future. The Roman finds are now partly in Netherby Hall and in the Tullie House Museum in Carlisle.

development

In 122 the Emperor Hadrian ordered a barrier wall to be built in northern Britain, reinforced by watchtowers and forts, from the Tyne to the Solway Firth, to protect the British provinces from the constant incursions of the Picts from the north. Most of the wall was built by soldiers from the three legions stationed in Britain and the Classis Britannica . Five forts (two of which were to additionally secure the tribal territory of the allied brigands ) were located as outposts north of Hadrian's Wall.

The Netherby camp was probably occupied by the Romans for over 300 years. The early wood and earth fort was built in the late 1st century AD (80) during the campaigns of Gnaeus Iulius Agricola . It was located in the middle of the Selgovae settlement area and secured a road crossing and a bridge or ford over the Esk during this time . Under Hadrian it was converted into a stone fort , possibly at the same time as the rampart and the other outposts ( Habitancum / High Rochester, Fanum Cocidi / Bewcastle and Blatobulgium / Birrens). Perhaps also to protect the wall construction site against attacks by hostile tribes. They were all about half a day's march from Hadrian's Wall.

Some of the 3rd century inscriptions found in Netherby suggest that the fortress was the headquarters of the Roman reconnaissance units on the northern border. His garrison was supposed to keep the northern tribes in check, secure the road to Birrens and Hadrian's Wall (Stanwix), and conduct apron reconnaissance. Judging by the finds, the camp was used until the middle of the 3rd century. The most recent Roman finds are coins from the time of Emperor Gordian III. (A.D. 238–244).

The fort was in use for a much longer period of time, probably well into the 4th century, as were the other four outpost forts on Hadrian's Wall. Under Constantine the Great , a large part of the Roman troops north of Hadrian's Wall was withdrawn from 312 onwards. Perhaps in the course of a peace agreement with the Caledons and Maeters, since he needed the soldiers more urgently for his war against Maxentius in Italy. The scouts stationed north of the wall are said to have been bribed in the course of the great barbaric conspiracy of 367, when the Picts , Scots and Anglo-Saxons invaded Britain together, not to report the deployment of the barbarian army. The fort is not mentioned in the relevant troop list of the Notitia Dignitatum . This could mean that it was no longer occupied by regular soldiers in the late 4th century. After the Romans had finally given up the island by 410, the fort - as happened in Birdoswald - could either have been taken over by a Romano-British warlord or destroyed by the Picts. Its ruins were obviously clearly visible for a very long time, as the travel reports from the 16th century show.

Netherby could also have been the site of the legendary Battle of Arfderydd (Athuret). This dispute is mentioned in the Annales Cambriae , in the entry for the year 573. One of the military leaders, King Gwenddoleu , may have holed up in the Roman fort ( " Caer Wenddolau " ).

A permanent tower house, a so-called peel tower, was built within the Roman walls in the 15th century . It was built mainly from the stones of the fort, which could be found in large numbers in the tower walls. At the end of the 1500s, Netherby was owned by the Graham family for the next 400 years. From this time on the house and its possessions prospered. The first extensions to the tower and the garden were probably made at the beginning of the 16th century. During this time the Border Reivers , looters and murderers who made the border area unsafe, could from King James VI. to be crushed. The last visible remains of the fortress and the vicus were removed in the late 18th century when the buildings were extended to create a representative aristocratic seat.

Fort

Presumably the remains of the fort are covered by the manor Netherby Hall, which stands on a small hill above the Esk river valley, which flows north past the property. From the inscriptions found on site, historians have deduced that the fort went through at least two (possibly up to four) construction phases. It was probably aimed at the esk . Its dimensions can only be estimated from the Roman garrison units stationed here. It is known that initially a 500-man infantry unit and later a (nominally) 1000-man cavalry regiment ( ala ) with around 300 horses were quartered in the fort. The warehouse should have occupied an area between 2.4 and 3.6 hectares. The Hadrianic stone fort probably had the long rectangular floor plan with rounded corners, which is typical for mid-imperial fortifications. It probably also had four access gates, plus the interior buildings that were standard for mid-imperial auxiliary troop camps. In the center these were the headquarters ( principia ), one or two granaries ( horrea ), horse stables ( stabula ), team barracks ( centuria ) and various functional buildings (workshops, latrines, bakeries). An inscription discovered in 1762 reports the completion of a riding and parade hall ( Basilica Equestris Exercitatorius ) by the Hispanic cohort, this happened in the early 3rd century. For archaeologists and historians, it is one of the most important written finds from Netherby, as it became known as the Romans called their riding arenas. In the auxiliary troop forts, they were mostly at the front of the principia. The only comparable buildings in Britain were in the legionary camp of Caerleon ( Isca Silurum ) and in the Wallkastell Birdoswald ( Banna ).

garrison

Castra Exploratorum was probably occupied by regular Roman soldiers from the 1st to the 4th century. During its existence it housed some cohorts of auxiliary troops ( auxilia ), but also legionnaires' vexillations. The latter were usually not assigned to garrison service at the border, but instead sent special forces for the more demanding construction projects in the forts. It is believed that the fort was continuously occupied during the Agricola campaigns around 80 AD. The type, strength and composition of the garrison at this time is unknown due to the lack of archaeological and epigraphic finds. The fort was probably also occupied by a number of spies. These units were later disbanded because they had actively participated in the 367 Barbarian Conspiracy.

The following units either provided the fort's crew or may have stayed there for a limited time:

| Time position | Troop name | description |

|---|---|---|

| 2nd century AD | Legio sextae Victrix ("the sixth legion, the victorious") | A fragment of the inscription from Netherby attests to the presence of soldiers from this legion. Construction or repair work was probably carried out inside the fortress at the end of the 2nd century during the reign of Commodus . Another inscription found there is also dedicated to this emperor. |

| 2nd - 3rd century AD | Legio secunda Augusta ("the second legion of Augustus") | The presence of members of this legion is known from several inscriptions. From this it is concluded that during the reign of Emperor Hadrian major construction work was carried out by the legion in the fort. The second legion was also used there for construction work during the 3rd century. |

| 3rd century AD | Legio vicesimae Valeria Victrix ("the twentieth Valerian legion, the victorious") | The Legion, together with the Legio II Augusta and the Cohors I Hispania , put an inscription during the governor Modius Julianus (219) . |

| 2nd century AD? | Cohors primae Nervanae (the first cohort of Nervi) | The troops were recruited from the Nervii tribe in the province of Gallia Belgica . It was a so-called Cohors Peditata Quingenaria , d. H. it consisted of around 500 foot soldiers. The unit is named for Netherby from a single (undated) altar to the god Cocidius and probably represented the first garrison of the Hadrianic stone fort. At that time, the command of the castle was a tribune named Paternius Maternus who had previously served in the Praetorian Guard in Rome . Due to its geological nature (altars from Netherby were usually made of red sandstone), the historian Eric Birley assumes that it was brought here from Bewcastle ( Fanum Cocidi ) . Perhaps the Nervier Cohort (or one of its departments) was stationed in Bewcastle in the 3rd century. The presence of the troops could also be verified for Vindolanda at Stanegate . |

| 3rd century AD |

Cohors prima Aelia Hispanorum milliaria equitata (the first cohort of Hispanics , 1000 men strong, partly mounted) |

The cohort originally consisted of 500 men and was raised from the Celtiberian tribes of the Hispanic provinces. It is very likely that it was increased to 1,000 soldiers in the second century. Aelia suggests that this happened during the reign of the Aelian emperors. This cohort left four datable inscriptions (from 213 to 222) in Netherby. An inscription, which was created between 215 and 220, reports on various works that she carried out together with vexillations of the Legio II Augusta and the Legio XX Valeria Victrix . Presumably the unit came to Netherby during the campaigns under Septimius Severus and Caracalla - between 208 and 212 - and was perhaps permanently stationed there after the end of the campaign. Two of their commanders, the tribunes [...] Maximus and Marcus Aurelius Salvius , are also known from these inscriptions. |

| 3rd to 4th century? | Numerus Exploratorum (scout / scout) | These special forces also belonged to the auxiliary forces and were recruited from tribes known for their good local knowledge and perseverance in hunting. They were only lightly armed and were mainly used as scouts in enemy reconnaissance. The name and serial number of the reconnaissance troops stationed in Netherby are - due to a lack of related findings - unknown. |

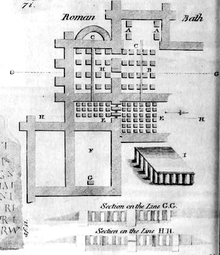

Bathhouse

The bathhouse ( balineum ), discovered in the 18th century, stood outside the fort walls ( extra muros ) because of the high risk of fire . It was oriented from east to west and was very similar to the specimens that were excavated at the ramparts of Benwell , Carrawburgh and Chesters (so-called row type). Leading experts in the field believe they were all built to a standard plan. The bathhouse was probably built around 222. It stood in a side street of the vicus. Its remains were examined superficially and a sketch made of it. In one of the rooms (room F in the plan) an altar for Fortuna with an inscription was found at the beginning of October 1732 , donated by a tribune of the Hispanic cohort. The exact location of the bath was also not recorded. It is believed to have been supplied with fresh water from a stream called Friar's Bush. If this was actually the case, it must have been northeast of the fort settlement or north of the camp. This avoided having to build a water pipe that crossed the route of the northwestern road leading into the north of Scotland. In two letters from 1734 the building is described as follows:

“ September 23, 1734 : This building consists of two larger rooms, which, I believe, have always been a little lower, because you can see the remains of steps leading down to them. The door sill is formed from three large stones, one in front and two on the sides, each about six feet long, with holes for hinges and locks. Each of the rooms is about nine or ten feet tall and divided from one another by a thin partition. Both were covered by the same arched roof, which the workers tore off. The outermost was used for a small temple of Fortune, because an altar and a pile of heads of various animals, especially oxen and sheep, were found in it. The interior was a bathroom and, in my opinion, was more intended for placing the bath tub. There is a cement layer here, which is made of lime and broken bricks. It covers both the floors and the walls and is very hard indeed. But I have no idea if it should ever hold water. Both rooms are covered with large flat stones. Below them is an aqueduct or some kind of long empty space or canal. It goes from one end of the building to the other. The floors are covered with cement to about 1 1/2 inches thick. I suspect because otherwise the stones were too cold to stand on. "

“ October 29, 1734 : The hypocaust (room E) was discovered in 1745, adjacent to the old bath, which was discovered in 1732. One hypocaust was supported by 54 stone pillars, which are marked as E on the plan. 36 of them were still covered with the floor made of flat stone and cement, as Figure I in the plan shows. The connection between its two parts consisted of three passages, marked as D. To the west of it was another hypocaust, supported by 20 pillars made of square tiles. A few were still covered with a little cement, marked with B. To the west of them there were four pillars, marked as A, of a similar construction. A canal, marked as C, crossed room B (from east to west), as well as in the adjoining room H. This was filled with bricks, including some hollow specimens. "

Vicus and port

Some of the inscriptions found in Netherby suggest that a larger civil settlement ( vicus ) had formed around the fort there over time . There are no remains to be seen. The settlement is likely to have spread on the area northwest of the fortress to the river bank. An inscription tells of the rebuilding of a temple. It probably dates from the middle of the 3rd century. According to the descriptions by Leeland and Bainbrigg found from there building remains, retaining rings and piers, as well as the observation of several streets that led north and south on the slope in front of the northwest corner of the fort to the north and south and to the Esk, the Romans may also have built a harbor on the riverbank. It is possible that the Classis Britannica had a few warehouses there but no naval base. Bainbrigge suspected that it was cut off from the Solway by silting up and therefore unusable. Presumably, its remains were also demolished for stone extraction from the 16th century.

Burial ground

William Stukeley claims to have seen a Roman cemetery during his visit, but he kept silent about its exact location. The burial ground was probably located southeast of the fort, furthest from the civil settlement. The existence of a burial ground near the fort is proven by the discovery of several Roman gravestones. One of the stones was set for Titullinia Pussitta from the Raetia province . The inscription, however, does not mention her husband's name or his military rank, which would be expected if she were the wife of a commanding officer. The lack of name, title and rank suggests that Titullinia was more the wife of a simple soldier, trader or craftsman, and did not live in the fortress, but outside the walls in the vicus. So far she is the only woman known by name from the area around the camp.

See also

literature

- William Camden: Britannia, 1607.

- William Stukeley: Iter Boreale, 1776.

- John Horsley: Britannia Romana or the Roman antiquities of Britain in three books. J. Osborn and T. Longman 1732.

- F. and C. Rivington: The British Critic, and Quarterly Theological Review, Volume 15, T. Rickary, London, 1800.

- Eilert Ekwall: The concise Oxford Dictionary of English Place-Names. 4th edition, Clarendon Press, 1936-1980.

- AL F Rivet, Colin Smith: The place-names of Roman Britain. Batsford Ltd., London, 1979-1982.

- A. D Mills: Oxford Dictionary of British Places names. Oxford University Press, 1991-2003.

- Eric Birley: Research on Hadrian's Wall, 1961.

- J. Collingwood Bruce, Charles Daniels: Handbook to the Roman Wall, with the Cumbrian coast and outpost forts. 13th edition, Newcastle upon Tyne, 1978.

- Chris Scarre: Chronicle of the Roman Emperors. Tames & Hudson, London, 1995.

- EJ Bickerman: Chronology of the Ancient World. Thames & Hudson, London, 1980.

- RG Collingwood, RP Wright: The Roman Inscriptions of Britain. Vol. 1: Inscriptions on Stone. Oxford 1965.

- Hans DL Viereck: The Roman fleet. Classis Romana. Köhlers Verlagsgesellschaft, Hamburg 1996, ISBN 3-930656-33-7 .

- Tim Clarkson: Scotland's Merlin: A Medieval Legend and its Dark Age Origins. Birlinn 2016.

- Robin Melrose: Warriors and Wilderness in Medieval Britain: From Arthur and Beowulf to Sir Gawain and Robin Hood. McFarland 2017.

Remarks

- RIB = Roman inscriptions in Britain

- ↑ IA 467/1 (Iter II), Rivet / Smith 1979-1982, p. 307, ND XL, 49.

- ↑ Iter II: "the route from the entrenchments to the port of Rutupiae , four hundred and eighty-one thousand steps", "A Vallo ad Portum Ritupas: A Blatio Bulgio / Castra Exploratorum XII / Luguvallio XII" , F. and C. Rivington 1800, p. 21st

- ↑ Camden 1607, p. 643, Stukeley 1776, pp. 57-58, Horsley 1732, pp. 78, 182 and 271, RIB 966 , RIB 967 . JCBruce 1851, 126, p. 353.

- ↑ RIB 995 ; Bewcastle, Eric Birley 1961, pp. 229-230, Robin Melrose 2017, pp. 24-25, Tim Clarkson 2016.

- ^ William Camden 1789, p. 195, RIB 968 , RIB 978

- ↑ RIB 975 , RIB 981

- ↑ RIB 974 , RIB 980

- ↑ RIB 980

- ^ RIB 966

- ^ RIB 980 , RIB 968 altar; RIB 976 approx. 213; RIB 977 approx. 213; RIB 978 222; RIB 979 ; approx. 215-220

- ↑ Letters from J. Clerk to a Mr. Gale dated September 23 and October 29, 1734.

- ↑ Viereck 1996, p. 254

- ↑ RIB 979 , RIB 984 , RC No. 156, Camden Britannia 1789