Hadrian's Wall

| Hadrian's Wall | |

|---|---|

| Alternative name | vallum Aelium |

| limes | Britain |

| Dating (occupancy) | 2nd to 5th century AD |

| Type | Barrage with watchtowers, mile fortifications, bridges and a system of ditches |

| unit |

a) auxilia , b) limitanei |

| size | Length: 117.5 km, width: 2.5-3 m, height: 5 m, wall volume: approx. 1,615,625 m³ |

| Construction |

a) Wood and sod construction, b) Stone construction |

| State of preservation | Stone wall, still largely visible above ground |

| place | Cumbria / Northumberland |

| Geographical location | 55 ° 0 ′ 44 ″ N , 2 ° 20 ′ 21 ″ W |

| Previous | Stanegate |

| Subsequently | Antonine Wall |

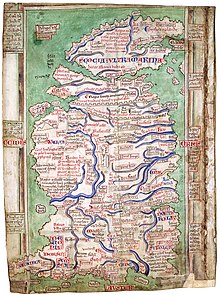

British Library , London

The Hadrian's Wall ( ancient Latin name may vallum Aelium ) was a Roman border fortification system of Britannic Limes located between Newcastle and Solway Firth , near the present border between Scotland and England in the UK , was created. It was built between 122 and 128 AD by order of Emperor Hadrian (76-138), after he had visited the northern borders as part of his inspection tour of all provinces of the empire. The wall extended over a length of around 117.5 kilometers. According to the prevailing view today, it did not serve to ward off invasions (the Roman limites were generally not suitable for this purpose ), but should primarily monitor trade and passenger traffic and canalize them at the border crossings provided for this purpose. a. enable the collection of customs duties. Furthermore, it was supposed to prevent minor attacks and the uncontrolled migration of Scottish and Irish tribes into the area of the province of Britannia inferior .

In its eastern part the facility consisted of a stone wall up to 4.5 meters high , in the western part it was initially just an earth wall . A trench system as well as 320 towers , 16 auxiliary troop forts and 80 mile forts were built to protect them . An almost identical - albeit simpler - security system, presumably consisting of up to 26 small forts with attached watchtowers and signal towers, was created on the west coast of today's Cumbria to protect the ramparts.

The remains of the wall still give an idea of how Rome's border fortifications once shaped the landscape. It was the result of a new foreign policy of consolidation and increasing isolation of the empire, which took its final shape under Hadrian. The wall was until the reign of Antoninus Pius , at whose instigation a new wood-earth wall system (" Antoninuswall ") was built on the threshold of the Scottish highlands , the northernmost border zone of the Roman Empire . However, this expansion could not be sustained for long (approximately from 141 AD to 180 AD). Hadrian's Wall and its forts were used again to monitor the border after the Antonine Wall was abandoned, until Rome left Britain to its own devices in the 5th century.

Large parts of the ramparts still exist today, especially in the middle section with the most impressive landscape. Mostly running on plateaus, you have a good view of the surrounding area from here. The ground monument is now one of the most famous tourist attractions in Northern England and was declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1987 . You can also comfortably hike it on the so-called Hadrian's Wall Path / National Trail and visit all relevant archaeological sites.

Location and topography

The rampart zone lay in the area of the Roman province of Britannia inferior , after the division in late antiquity on the area of the province of Maxima Caesariensis , which encompassed the whole of northern Britain.

Up to Wallsend the mouth of the Tyne formed a natural border to the east coast. The wall stretched over 117.5 kilometers (78 Roman miles), starting in the east at Segedunum , from the north bank of the Tyne eight kilometers overland to Fort Pons Aelius (now Newcastle upon Tyne ), Condercum (now Benwell ), Coriosopidum (now Corbridge ), Luguvalium (now Carlisle ), to name but a few, to the westernmost Maia Fort (now Bowness-on-Solway ), where it ended at the Solway Firth . This is a fjord that opens to the Irish Sea after 30 km . After Bowness-on-Solway, the fortifications continued along the west coast of Cumbria, reinforced by a series of small forts and towers - south to Maryport. All of these places are north of a once important Roman military road and border marker, the so-called Stanegate between Carlisle and Corbridge, which intersected there with Dere Street, which led to Scotland. The wall closes the isthmus between the mouth of the Tyne and the Solway Firth and connects over the central hill country of the Pennines , the mountains in the west of the island with the eastern heights. The wall terrain averages 150 meters above sea level and reaches its highest point at the Whin Sill's (680 meters). This area was used intensively for agriculture even before the arrival of the Romans. The isthmus was ideal for the construction of a barrage, also because natural border markings - such as rivers - are missing in this region of Britain.

course

The route on the northern side of the river valleys of Tyne , Irthing and Eden was known to the Romans since the Agricola campaigns in the 1st century. The military road of the Stanegate , secured by forts and watchtowers , which had marked the northern border in Britain since 105 AD , ran in the valley floor . In contrast to Stanegatestrasse, which essentially followed the valleys, Hadrian's Wall ran as far as possible on the ridges of the hills. From the east the wall stretches from Wallsend to Chesters and from there began to climb over its northernmost point, Limestone Corner, to the impressive basalt cliffs of the Whin Sills, from where you have a good view of the surrounding area. These, a 20-meter high corridor made of volcanic rock, then drop off steeply to the so-called Craigs. At Willowford the wall crosses the Irthing and now adheres closely to its north bank. West of Carlisle, the wall finally reaches the Solway Marshland, where it runs between Burgh-by-Sands and Bowness-on-Solway on a line just above the high water mark. From Bowness, the border fortifications along the coast of translated Cumbria continued.

development

Although they ruled Britain for around 400 years, the Romans did not manage to take control of the entire island. Emperor Claudius and his successors were only able to largely “Romanize” the south and east. The wild and restless tribes of the north, on the other hand, could not be dealt with by military means alone in the long term, the country was climatically much rougher than the south, the supply routes longer and the economic yield of this region for the Romans ultimately far too low to bear the costs and effort to compensate for the larger army of occupation. Under Emperor Domitian , the Roman army withdrew from Scotland (Caledonia) and first established the border - at about the same height as the later wall - at Stanegate. At the same time, under Trajan, the Stanegate line was strengthened with new forts, thus temporarily securing the new northern border.

2nd century

Even at the beginning of Hadrian's reign, Britain was still far from being a completely pacified province. Coin issues during this period identify Britain as "in constant defense," an indication that is also supported by archaeological evidence. 122 Hadrian also visited Britain during an inspection tour through the western provinces:

“Hadrian went to Britain; here too he ordered many improvements. He built a wall over 80 miles long to separate the Romans from the barbarians . "

A badly damaged inscription from the church of Jarrow on the south bank of the Tyne gives the reason for the construction of the wall:

“The son of all deified (emperors) emperor Caesar Trajanus Hadrianus Augustus, after the necessity of keeping the empire within its national borders, after the barbarians had been dispersed and the province regained, set a limes between the ocean coasts of Britain by divine providence Miles, which the army of the province built as a wall, under the supervision of Aulus Platorius Nepos the legatus of Augustus Propretor. "

This is the only inscription known to date that explains the reasons for the construction of the wall. Large parts of it have not survived, however, but were reconstructed by Anthony Birley , including the words and Latin terms that describe the wall in more detail. According to Birley's interpretation, it was officially his divine origin and providence alone that prompted Hadrian to award the army the major contract to build the wall after the pacification of the province of 122. The wall is referred to as the limes between the straits on the one hand and the opus valli of the army on the other . A clear distinction is made in the reconstruction between Limes and Vallum ; the reason for this lies in the assignment of the concepts to the acting personalities. This means that the emperor, enlightened by the gods, marks a lane over the island, which is then fortified with a wall by the army. A significant finding is also a - probably in the mile fort 38 (Hotbank) inscription of - excavated Legio II Augusta that Hadrian called and the reigning Britannic governor. It dates from the time the wall was built (122–125), and clearly proves that the wall was commissioned by Hadrian and not - as claimed in the decades-long wall controversy - by Septimius Severus .

Soon after Hadrian's death (138), his successor Antoninus Pius had most of the border troops relocated from the recently completed Hadrian's Wall 160 kilometers further north, where they started building one on the much shorter Bodotria ( Firth of Forth ) - Clota ( Clyde ) line new border installation, the Antonine Wall , began. The Tyne and Irthing valleys, which had been the scene of brisk military activity for more than 20 years, emptied again. The bulk of the soldiers withdrew, and with them undoubtedly the majority of the civilian population.

Nevertheless, the permanent subjugation of the tribes living in the Lowlands failed , and about 20 years later Emperor Marcus Aurelius ordered that the Antonine Wall be partially vacated and most of the troops relocated back to Hadrian's Wall. Some forts in his apron, such as High Rochester ( Bremenium ), remained occupied to demonstrate that the Romans had not withdrawn and left the area completely to the southern Scottish tribes. Hadrian's Wall itself had never been completely abandoned in the meantime, only a few superfluous gates had been bricked up. The rest of the teams looked there to see if the fortifications, which were built with such great effort, were not plundered. At the latest from 164 he was put back into full operation; some repair work can even be dated back to 158. All this happened under the governor Calpurnius Agricola , who is mentioned in inscriptions from the castles Carvoran ( Magnis ) and Stanwix ( Uxelodunum ) . If at that time parts of the wood-earth wall still stood in the western sector, they must also have been replaced by a stone wall at that time in order to, among other things, a. also to effectively prevent the smuggling of goods to the north, because this - and not the defense against attacks - was the most important task of the wall garrison.

Nevertheless, the Roman army in the north apparently found it difficult to maintain the peace. In a letter to Mark Aurel around 166 , Marcus Claudius Fronto described the Wallzone as a loss-making section. Cassius Dio reported heavy fighting with the northern tribes during the early reign of Commodus (180–192):

“Commodus also had to fight some wars with the barbarians on the other side of Dacia , with Albinus and Niger, the later opponents of the emperor Severus, gaining fame. But his war in Britain was of the greatest importance. The tribes on the island crossed the wall that separated them from the Roman army camps, committed numerous acts of violence and killed a general and his soldiers. "

Some forts, such as Birrens ( Blatobulgium ) and Haltonchesters ( Onnum ) were destroyed. Cassius Dio goes on to report that one of the two walls played an important role in these disputes; which of them, however, remains in the dark. It is mostly assumed, however, that this was Hadrian's Wall, perhaps in connection with the then partially abandoned Antonine Wall . However, the unrest has apparently been put down as a coinage from AD 184 glorifies a "Victory in Britain" (Victoria Britannica) . Major construction work on Hadrian's Wall followed. Towards that were partially demolished in the central section of the ramparts were rebuilt up to the edge of the battlements. In the west, the earth wall was replaced by a stone wall, the quarry stone core of which was bound with particularly hard and lime-rich mortar. The six ramparts between Birdoswald ( Banna ) and Bowness ( Maia ) were replaced by stone structures. In Chester-le-Street (Concangis) fresh water was supplied through an aqueduct in the northern apron. At the outpost fort Risingham ( Habitancum ) the wall and a gate were renovated, High Rochester (Bremenium) received gun platforms .

According to many researchers, the last Roman troops were withdrawn from the Antonine Wall in the course of these battles and subsequent reorganizations, and Hadrian's Wall marked its northern border until the Romans withdrew from Britain.

3rd century

At the end of his reign, in the early 3rd century, the terminally ill Septimius Severus and his sons Caracalla and Geta led a costly campaign in the tribal areas far north of Hadrian's Wall. In the preparatory phase, a large number of military structures along the wall were repaired. The demolition of watchtowers and the downsizing of some forts may also have been carried out during this period. Repairs to a granary for fort Banna / Birdoswald have been reported in the years 205–208, the former riding fort South Shields / Arbeia was converted into a supply center with 20 warehouses. Severus died in York (Eburacum) in 211 . After Caracalla's peace agreement with the Caledonian tribes, the northern regions experienced a relatively quiet period again during the 3rd century. The peace with the northern tribes seems to have lasted for a relatively long time. The Romans controlled the ramparts as far as the banks of the Tay . Around 220 u. a. some watchtowers were torn down and the top of the wall was renovated with the material obtained in this way. In the period that followed, up to 240 major repair work was documented on Hadrian's Wall, which has now finally established itself as the northern border of Britain. It is unclear whether these construction measures were related to incursions by the Maeataea .

During the reign of the usurper Carausius , the wall had become dilapidated again and was probably partly destroyed during fighting; this could be connected with the withdrawal of a large part of his garrison, since Carausius' successor, Allectus , urgently needed the soldiers to defend the Channel coast against the Caesar of the west, Constantius Chlorus . Due to the lack of sources about the time of the reign of Carausius and his successor Allectus, it is difficult to work out the differences and changes during their reign. The problem with this is that generally little is known about the conditions in Britain at that time. That is why most of the statements about it are to be classified in the area of speculation. Archaeological research has shown that the condition of the wall at the time the island was reconquered by Constantius Chlorus must have been miserable. The reason given for this is that hardly any repair work has been carried out on the border wall in the previous fifty years. Since Allectus had evidently withdrawn most of the occupation troops from the northern border, the border wall was almost not defended, and the tribes north of the wall had an easy time invading Roman territory again without danger. It is believed that further destruction of Hadrian's Wall occurred. However, since the sources do not express themselves clearly in this direction and the archaeological research does not provide any clear findings, this remains only a guess. That the destruction was caused by these looters has also not been proven archaeologically. An inscription from Birdoswald from the period between 297 and 305 mentions that various buildings had fallen into disrepair and some had already collapsed, but were completely rebuilt at that time. These reconstruction measures may also have included the praetorium and the thermal baths of the fort. These apparently seem to have had no practical use for the occupation there for a longer period in the history of this fort, since there are no indications of their destruction by enemy action. The above-mentioned inscription from Birdoswald speaks of natural decay, not destruction, so that repair work on other fortifications at the same time could be part of a routine renovation campaign. Some accommodation barracks were completely rebuilt, the classic, strip-shaped rooms replaced by individual chambers, as has been found in Housesteads and Wallsend . Conversions to milestones, gates or the construction of a completely new gate at Knag Burn - near Housesteads - are further examples of extensive renovations that were carried out on the wall at that time. This shows that a large part of the wall's infrastructure continued to be maintained and thus received state support. The fact that no signs of such renovation measures could be found at other forts, such as Haltonchesters , can also mean that repairs either did not seem necessary or the fort was temporarily unoccupied . This does not seem absurd when you consider how much time had passed since the erection of Hadrian's Wall. The soldiers who once built the wall were as far removed from the garrison troops in the 4th century as they are today in Napoleon's era . In this context, it is easier to understand why the wall fell into disrepair over and over again and was then repeatedly renovated over long stretches.

4th century

Shortly before the year 300 we heard of a new tribal coalition in the north, the Picts . These presented Rome with great difficulties in the fourth century. Emperor Constantius Chlorus went to Britain between 305 and 306 to take action against them. Before that, he may have had some of the forts on the wall repaired. However, he died soon after during his stay in Eburacum (York). His son Constantine was proclaimed emperor by the army in 306 and may later return to Britain for further campaigns. Among other things, coin issues from the years 313-314 AD indicate that Constantine must have traveled there at least once, as there had obviously been great unrest there, which made the renewed presence of the emperor imperative. It can be assumed that the tribes north of Hadrian's Wall had not stopped their attacks. Rather, the destruction of the outpost forts at High Rochester, Risingham and Bewcastle, all of which can be dated between the reconquest of the island by Constantius and the year 367, indicates that a massive attack must have taken place there, possibly by the Picts with the support of the Caledonians. His son and successor, Constans , stayed there in the winter of 342–343. In the 4th century the situation in Britain became more and more threatening, because even its island position could not protect it from the effects of the so-called migration in the long term . External attacks and civil wars increasingly weakened the empire's defenses. The Romans resorted to recruiting foreign mercenaries ( foederati ) due to recruitment bottlenecks . In Britain these were often Anglo-Saxons trying to get their share of the prosperity of the Roman Empire in this way. Together with Roman border troops ( limitanei ) they defended the British provinces, which were now divided into five administrative units. Written sources report that the situation on the northern border in Britain was viewed as worrying by the Roman leadership at the time. Major military operations designed to retaliate and deter the Picts are reported between AD 306 and AD 367. Thereafter, in 360 and 367, there were again unrest on the northern border. In the following years, several tribes allied to invade Britain. They included the Picts from Caledonia, the Scots and Attacotti from Ireland, and the Franks and Saxons from the continent. Although the attackers penetrated deep south, a direct attack on Hadrian's Wall is not mentioned. Rome put an army on the march in 360 under the command of the proven Comes Theodosius to end the chaos there - which had broken out by the concerted barbarian invasion - and to bring the British provinces back under imperial rule. The rampart zone was probably also affected, but there are no archaeological signs of major destruction during this period. Presumably, the attackers did not want to lose valuable time storming and burning the forts, bypassed the wall by sea and, after overcoming the wall, immediately turned to the more prosperous provinces in the southeast, where much richer prey beckoned. The Caledonian tribes do not seem to have been interested in a permanent occupation of the country. In response, Rome set up its own cavalry units ( Equites Promoti ) in order to be able to counter this threat more effectively. However, this led to the best and most powerful troops being withdrawn from the border.

Repairs to the wall are only known from later inscriptions ( Ravenscar ); some of them mention the involvement of southern British tribes such as B. that of the Durotriges. Probably all provincial residents able to work were obliged by Theodosius to repair the damage after restoration of peace and order. In order to secure the flanks of the rampart zone, watchtowers and forts were again built or repaired on the east coast of Cumbria over a length of 42 km. The outpost forts north of the wall were no longer occupied. The acts of war on the northern border continued, with a Roman campaign in 383 and further incursions until the year 400. In the course of the usurpation of the Comes Britanniarum , Magnus Maximus , around 388 the last Roman coins were struck on British soil. It is also believed that Maximus withdrew all Roman garrisons from Wales in 383 for his Gaul campaign against the legitimate Emperor Gratian . However, their number was probably not nearly enough, and so he had to add a large part of the garrison units on the northern border to his army for his project. This probably led to the fact that Hadrian's Wall was not adequately guarded at that time. For this reason, the forts on Wall ceased to be part of a uniformly organized border security system at the end of the 4th century. The withdrawal of the troops by Maximus actually heralded the end of the Roman military presence in Britain. From this point on, more and more independent regional rulers or “ warlords ” took control of the British provinces with their own private armies (bucellari) . In his work " On the Destruction and Conquest of Britain ", written around 540, the monk Gildas also refers to these events. He reports that Britain was stripped of its soldiers and the prime of its youth when the usurper Magnus Maximus crossed the continent with the British Provincial Forces. The soldiers did not return afterwards. The Provençals, “ignorant of the art of war”, suffered increasingly from the attacks of the Picts and the Scots and urgently asked Rome for military aid. Thereupon a legion was put on the march, which drove the barbarians out again. The Romano-British were also instructed to build a wall from one sea to the other. But since it only consisted of turf bricks instead of stone, it was of no use to the “stupid people”, Gildas sneered. No sooner had the Legion withdrawn than the old enemy overran the whole country again and slaughtered its people.

In 399, Stilicho sent a powerful army to Britain for the last time to repel invaders from the north. The provincial contingent was reinforced by around ten units, and at the end of the 4th century a mobile field army ( Comitatenses ) was set up to better defend the island. The soldiers instructed the Romano-British in the manufacture of new weapons (exemplaria armorum) and probably also helped them to repair Hadrian's Wall again and to erect new watchtowers on the west coast. But Rome withdrew its intervention troops as early as 400.

5th century

There can be no doubt that the garrisons in Britain were successively withdrawn by Maximus, Stilicho and Constantine III. have been greatly weakened. Nevertheless, the wall was not completely abandoned after the end of the 4th century. The latest archaeological findings have shown continuous use well into the 5th century. More recent archaeological finds show that at least some forts on the wall were still inhabited by the descendants of the Roman soldiers up to around 500. Most of the fortresses of the 2nd century, which were built according to a uniform construction scheme, were no longer recognizable. In terms of interior development, irregularly laid out, nested and simply designed buildings predominated. The principia and warehouses had either been converted for residential purposes or as assembly halls or had been allowed to deteriorate. The bathhouses no longer served their previous purpose. The guards often lived for years - or for several generations - with their families in the same quarter and stayed there long after the central military organization had ceased to exist.

With the withdrawal of the British field army ( Comitatenses ) by the usurper Constantine III in 410 at the latest . the wall probably lost more regular soldiers. However, only very few border guards followed Constantine, as they probably ran their own farms on the side. Most of these men were born in Northern Britain. The greatly shrunk guards continued to defend the wall as best they could, in the hope that Ravenna would again send an army to Britain, but this no longer happened. According to the Notitia dignitatum Occ. (ND) at that time the wall was still guarded by regular limitanei along its entire length . The list of troops of the Notitia was probably long out of date when it was drawn up, as it still lists many units from the Middle Imperial period, on the other hand the lack of outposts in the list speaks for its topicality at the time. There was no longer a central command on the Wall either issuing orders or regularly sending supplies. This promoted the transformation of the regular units into local militias. It is likely that the last regular Roman garrisons lasted until at least 407. What happened next on the wall is largely in the dark. Since no more Roman coins could be found in the forts in the strata of the following period, it was initially assumed that they had been abandoned. But it doesn't have to be like that everywhere on the wall. Money transactions soon became superfluous due to a lack of coins and the resurgent barter trade. This worked e.g. B. in trading in agricultural products quite well. The complex, previous economy, which was mainly geared towards the needs of the military, collapsed due to lack of purchasing power.

After the collapse of Roman rule, small farms and some larger estates from Hadrian's Wall to the Humber in the southeast and Chester in the southwest formed the economic backbone of the north. They were under the control of the commander of the border troops based in the legionary camp of Eburacum . Magnus Maximus probably appointed a certain Coel (lat. Coelius or Coelestinus) as commander in chief of the northern border; he should be the last official, d. H. Dux Britanniarum appointed by the Roman high command . Early Welsh traditions (such as the Bonedd Gwŷr y Gogledd, = "The descendants of the men of the north") report u. a. by a mythical king named Coel Hen ( Cymrian : the old Coel), he is said to have been the progenitor of all independent Romano- British kings of the north. Coelius and his troops continued to protect the provinces in the southeast from incursions by the Picts from the Scottish Lowlands and in return received his supplies from these regions. However, with the merger of the Caledonian kingdoms north of the Forth and the Clydes, the incursions of the Picts increased. Hadrian's Wall, which was probably already largely dilapidated, was still - poorly - guarded, so that it was safer for looters to bypass it by sea without being observed. However, the coastal residents were usually able to be warned of them in good time by the crews at the signal stations. The Picts therefore relocated their raids further south, where they quickly reached the even more prosperous regions of the island on the well-developed Roman roads. At some point, however, the Dux of the North apparently received no more support from there, as the people there resumed pre-Roman customs and the administrative districts of the late Roman provinces were transformed into independent, fighting small kingdoms through inheritance. He therefore only fought the looters if they endangered his territory and left the south to itself.

After the state sources of supply had dried up, its residents probably only started to secure their immediate surroundings and became defense farmers. It is also conceivable that they sometimes ventured into the even better-off southern provinces of the island. During this time the fortresses were either transformed into fortified villages (oppida) or were abandoned and only used as quarries; some of the mile forts were used as cattle pens. It seems that after 410 some of the former military camps served as residences for local rulers. These men presumably came from the local upper class and were probably mostly officers in the past. The most successful later founded their own royal dynasties. The soldiers still remaining on the wall put themselves in their service, as only then could they and their families be adequately supplied with everyday necessities.

There are numerous indications that many of the fortifications were not abandoned after 410. The Birdoswald camp was inhabited for many decades afterwards. Excavations revealed that its infrastructure continued to be used until it finally became completely unusable and had to be replaced by simpler wooden buildings. Its inhabitants, presumably mostly the descendants of the Roman garrison soldiers, now managed to survive as a largely autonomous and rural community. The ruler resident there had over the ruins of one of the grain stores u. a. have a large hall built out of wood. It is believed that several other forts on Hadrian's Wall were used in this way and thus enabled the Romano-British communities to resist attacks and infiltration by the Anglo-Saxons, Picts and Scots. For some time, the Romano-British residing on the wall were able to prevent the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Bernicia , whose metropolis was in Bamburgh , at the eastern end of the wall, from expanding further. They arguably continued to maintain the traditions and culture of the military units to which they had once belonged; Traces of such activities were found all over the excavation sites along the wall. What happened in Birdoswald could therefore have happened in the same way - or at least similarly - elsewhere in the Wall Region.

In the second half of the 5th century the so-called " Dark Age (actually without writing) " began for Britain . What exactly happened during this time can no longer be fully reconstructed today due to a lack of epigraphic sources. It is believed that the Anglo-Saxon mercenaries recruited by the Romano-British mutinied around 440, then settled their tribesmen on a large scale in Britain and thus gradually gained control of the entire former Roman province.

6th century to modern times

At least for Northern Gaul, the Liminate of the Rhine Army has written evidence of the adherence to the late Roman military order and culture up to the 6th century. There is therefore nothing to be said against the assumption that this was the same in Britain. The inscription on a tombstone from Vindolanda, for example (today in Chesters ), is written in a very wild Latin that no longer belongs to a classical Roman, but rather to an early medieval Christian cultural community. Although it cannot be dated exactly, it probably dates from the early 6th century.

The Greek historian Prokopios of Caesarea , who never entered Britain, also mentioned a wall (teichos) around 550 that divided the island of Brittia into a Roman and a non-Roman part that was hostile to life and was built "in ancient times". It is noticeable that, on the one hand, Prokopios' source still knew about the complex, but on the other hand, it does not seem to have been informed that the wall was built by the Romans. The monk Beda Venerabilis describes the wall in the 7th century as 2.4 meters wide and six meters high. It was undoubtedly a practical source of building materials for a number of new buildings, including the monasteries at Jarrow , Monkwearmouth and Lindisfarne, even then .

In spite of everything, the wall seems to have been preserved well into Elizabethan times. In the 16th and 17th centuries, the former wall zone was notorious as a hiding place for cattle thieves and highwaymen (" Border Reivers ") who made the border area with Scotland and Yorkshire unsafe. After the death of Elizabeth I, the anarchic conditions along the border became untenable, so that the government in London for the fight against gangs u. a. also considered the revitalization of Hadrian's Wall. From this time on, the wall, which had become useless, was increasingly destroyed by stone robbery. Their building materials were needed much more urgently for new houses, churches, farms in Cumbria, Northumberland and Tyne and Wear , including the construction of the Lanercost Priory monastery complex . Much of the material was used in the 18th century by General George Wade (1673–1748) to pave a military road (today's B6318). The road was intended to enable the British heavy artillery to be quickly moved from Newcastle to Scots-occupied Carlisle during the crushing of a Scottish revolt under Charles Edward Stuart (Bonnie Prince Charlie) in 1745. In the first decade of the 19th century, well-known antiquarians began to take an interest in the wall, and from the middle of the century great efforts were made to preserve the last remains of the wall for posterity.

function

Archaeologists and historians debated the real purpose of the wall for a long time. For a long time it was believed that it was built to create a barrier between Roman civilization and the barbarians. The situation at that time was probably much more complex. For decades, the border in the north was only marked or secured by the Stanegate and a chain of fortifications. Now it was made unmistakably clear to the northern tribes that the Roman Empire with all its achievements (e.g. legal security) began on the wall and that it knew how to defend itself effectively. In addition to its (minor) military protective function, the wall was therefore primarily used to demonstrate Roman power, architecture and engineering.

Hadrian's new border security concept was to establish the limits of clearly identifiable natural obstacles such as rivers and mountain ranges final and the gaps between them with artificial fortifications earthen walls or palisades as the limit between the Roman provinces of Germania , Upper Germania , Raetia and Germania magna - from which the Romans had to retreat after their defeat in the Varus Battle - to be permanently secured or marked. Hadrian's Wall was also one of this new type of fixed border control system. Once peace at the border was secured, the emperor thought, the Romanization could progress and the economy could develop undisturbed according to the Roman model, which in turn was inevitable for later tax revenues. The land north of the ramparts was barren and rough, while south of it there was plenty of good pasture land. This difference can be seen particularly well at Grag Lough. The area around Chesterholm / Vindolanda is also very fertile. The wall also drove a wedge between the belligerent highlanders and the Pennine tribes south of the Tyne. In this way, a potential danger was neutralized that had probably already caused great difficulties for the crews at Stanegate.

Hadrian also realized that Britain could become a source of something even more valuable than gold at the time: soldiers. The best prerequisite for this was its short land border. Most of the provinces Hadrian visited had very long borders that required many soldiers to secure. There were no such difficulties in Britain, all that was needed was to effectively and permanently keep the tribes in the north away. The Historia Augusta gives another hint in this regard: It reports that the emperor in Germania had introduced a much stricter service order for the border troops. It is almost certain that Hadrian took the same measures in Britain. The Historia Augusta also speaks of a lot of problems in the province, but does not go into these in more detail. Years of ineffective advances and retreats in the north must have had an increasingly demoralizing effect on the soldiers there. The construction of the wall was probably also a means of raising morale through a meaningful occupation and at the same time offered the side effect of joint probation in a large project that promised a benefit for everyone. In addition, the Romans also maintained forts ( Netherby , Bewcastle and Birrens ) in the northwestern apron in order to keep the Glacis des Walles and the area of the allied Brigantes better under control. In the east the camp secured by Risingham and High Rochester the Dere Street , the main transport and supply road to Caledonia. Determined attackers, however, had no major difficulties in climbing over a poorly secured point: the wall was just as unsuitable as other border fortifications at the time to ward off serious military attacks. In the military sense, however, the wall formed a safe base for deployment or retreat for the Roman army, and under its protection an advance to the north could be prepared at any time and unobserved.

Nevertheless, the wall with its few, certainly strictly guarded crossing points made it possible to monitor the daily travel movements of the tribes close to the border, whose ancestral areas the wall presumably intersected, just like at today's border crossings, which also channel traffic to certain control points (for example between the USA and Mexico or between Syria and Turkey). Similar to the Upper German-Raetian Limes, Hadrian's Wall was primarily a monitoring system for times of peace. In the exclusion zone between the wall and the southern ditch, individuals or groups who passed the wall from the north with their merchandise could be compelled to pay taxes, and their further south or the smuggling of goods and weapons on a large scale could be prevented. The border thus remained permeable and represented an additional source of income for the Roman tax authorities. Whether this income made up for the personnel and material expenditure that the Roman state made on the northern border is questionable.

Construction and building history

On the basis of coin finds in the Birdoswald castle , it is assumed that the western sector of the rampart zone could have been secured with a continuous earth wall as early as the time of the Traian. The construction work on Hadrian's Wall probably began as early as 120 AD. H. even before Hadrian's visit to Britain. There is epigraphic evidence, such as a letter from Vindolanda and other texts, that the emperor himself determined the course of the wall. The work was under the supervision of the governor Aulus Platorius Nepos, a personal friend of Hadrian, he had accompanied the ruler of Germania to Britain and was installed in his new office in the summer of 122. Around the years 126–127 he was followed by Trebius Germanus, who let work on the wall continue.

Work began along the entire route with laying the foundation. In its earliest construction phase, the barrage consisted of a stone and wood-earth wall, some of which were built on bridges over the rivers Tyne, Irthing and Eden. The forts and towers on the south side were built first. The gaps in between were probably temporarily closed in part with a wood-earth wall, also because the border regions, as was determined by means of pollen analyzes, were largely deforested 600 years before the arrival of the Romans in Britain and thus the material for conventional palisades was missing. Around 125 AD, either under Nepos or under the new governor, the structure of the fortifications was changed: From tower 26B to Irthing (Willowford near Birdoswald) the wall was only 2.5 m thick. The mile fort and watchtowers were later connected to the wall by means of their wing walls. The foundations were originally intended for a much wider wall (this could be proven by digging stitches), but ultimately only a slightly narrower version was realized. One explanation for changing the original plans would be that existing or poorly positioned forts had to be integrated or removed along the planned wall line.

The remaining distance (45 km) from the Irthing to the Solway Firth near Bowness-on-Solway on the west coast was initially secured with a 5.9 m wide wood-earth wall at the base. Presumably there weren't enough stones available there. It presumably rose steeply on the enemy side and gently sloped down again on the rear. At the east gate of Birdoswald there are still remnants of the original wood-earth wall. Between sections 49 and 54 (Gathside), the wood-earth wall slipped in places in the late Hadrian period and collapsed. The gap was closed with a stone wall at this width. The watchtower 54A also had to be rebuilt. The wood-earth wall was finally largely replaced by a 1.8 m wide stone wall in Severan times.

In the east the wall had been built of stone from the beginning; For the first few kilometers it ran a little further north than the original wood-earth wall. The foundation consisted of broken stones that were only partially mortared or bound with clay and a plinth of different heights made of three to four layers of stone. It was estimated to be between four and five meters high and consisted of two ashlar formwork, which was attached to a pounded cast mortar core made of rubble stones on both sides with a mixture of sand, lime and animal blood as a binding agent. The wall has no scaffolding holes and clearly receded on both sides. The humid climate in these latitudes also had to be taken into account: At regular intervals (2.4 m), a later-made canal runs under the wall to divert the rainwater into the north ditch. What it looked like in the upper part is unknown. At Wallsend you can see a five-meter-high, battlement-reinforced reconstruction of Hadrian's Wall. The parapet walk probably continued on the three ramparts. Whether the wall was plastered along its entire length, as some findings indicate, is still controversial. In front of the wall, a trench that was not completely continuous was dug.

Most of the building material had to be brought in from ten to twelve kilometers away, from quarries in Cumberland . These breaks could be located on the basis of inscriptions on both sides of the rampart zone. The lime pits were right next to the construction sites. An attempt to calculate the cost of materials for the entire system as precisely as possible led to the result that around 3.7 million tons of stones were required for its completion. Peter Hill even came to the conclusion that up to 18 million stones were built into the wall. The ashlar stones are small, only 20 to 23 cm square. This seems unusual at first, until you consider that everything had to be built by hand, largely without aids such as cranes or pulley blocks. It is estimated that the Roman stonemasons needed around 20 minutes to complete such a block. In some cases, there are also unprocessed stones in the casing, which suggests great time pressure during construction.

Presumably the wall was not completed according to the original plans. In order to reduce the workload, the wall, which was initially around three meters wide, was narrowed to 1.8 to 2.4 m. In places they changed their course a little to better adapt them to the terrain. Events such as epidemics , acts of war or the withdrawal of entire garrisons often forced the Romans to compromise when carrying out their building projects. Transport logistics also posed major problems. It is unclear whether the full length of the wall was completed; in comparison with other major Roman projects, it does not seem impossible that it was only a temporary solution. The wood-earth wall in the western sector also supports the theory that it was of great importance for the builders to complete this barrage as quickly as possible.

Organization and manpower

The legions and auxiliaries stationed in Britain were used for the construction work . At first glance, the mile fort and towers seem indistinguishable from one another, and yet there are architectural differences - especially in the design of their entrance gates and their orientation. According to the building inscriptions found all over the wall, each of the three legions may have partially realized their own ideas in their section. Since these occur repeatedly at different points on the wall, it was initially assumed that the building lots were allocated to the three “legionary units” in the same area in terms of area. These were then carried out by the cohorts and centurions on their own responsibility and based on the plan. However, recent investigations on the sections at Northtyne and Irthing showed that probably only two construction teams were responsible for carrying out the project. In view of the typically Roman planning efficiency and the logistics required for it, this also makes more sense. Smaller, independently working construction teams would probably only have hindered each other on shorter distances. Each assigned construction lot stretched for about eight to ten kilometers and was dependent on the nature of the terrain. The division of the sections among the various units served to optimize the existing workforce, was an incentive for productive competition and was intended to form groups that worked as cooperatively and as smoothly as possible.

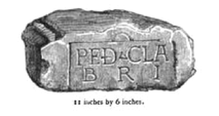

After the construction work was completed, an inscription plaque was placed on each section of the wall that was removed, indicating the units involved in the construction and sometimes the names of their officers. A considerable number of these - mostly only roughly executed - inscriptions have stood the test of time and are now exhibited in the museums along the wall. The museum in Carlisle owns 36 of them, proving that Legionnaires weren't the only ones involved in its construction. A specimen that comes from the area around the Birdoswald castle names marines:

[ PED ] ATURA [ CLA ] SSIS [ BRI ] TANNICAE, "this length was built by the British fleet".

Others again mention legionaries:

[ LEG ] IONIS [ II AUG ] USTAE [ COH ] HORS [ VII SU ] B [ CU ] RA ..., "from the second legion of Augusta, the seventh cohort under the command of ..."

Unfortunately, this inscription is incomplete. It was found at the so-called "High House Castel" ( Meilenkastell 50 ), which could only have been built by special forces. Such work was carried out by skilled workers ( immune ) who were also assigned by the legions. Simpler work - like digging the trench, for example - was mostly done by the auxiliaries, the discovery of a stone south of the wall with the following inscription attests to this:

[ C ] OHORS [ IIII LIN ] GONUM [ F ] ECIT, "The fourth cohort of Lingonians did this".

However, it does not appear that this can be assumed for the excavation of the trench in the northern section of the wall or even for the entire length of the trench. A geologically particularly problematic section was Teppermoor Hill, also known as "Limestone Corner", at the northernmost point of the wall. Here, the otherwise easy-to-manage excavation of basalt rock was disturbed, which required specialists particularly well versed in stone processing in order to move forward. A large boulder, originally weighing 13 tons, lies - split into three parts - in the middle of the trench to this day. The Roman workers chiseled holes in its top to prepare it to break wooden wedges softened with water. Apparently the work was stopped beforehand. Presumably, o. A. Difficulties in completing the trench. At the end of the 2nd century, according to building inscriptions, civilians from the " civitates " of the Carvetii , Brigantes and Dumnonians were also used for construction work on the wall. The so-called "Civitas Stones" are all undated. They probably date from the time between Hadrian and the end of the 4th century. The two westernmost specimens were discovered in the section of the wood-earth wall between the transition at Irthing and Bowness-on-Solway. The inscriptions could also be related to the renovation and reconstruction work in the early 3rd century under Emperor Septimius Severus.

Fixing and security systems

Even before the wall was completely finished, the fort crews of the Stanegate were relocated directly to the wall around 126 AD. Up to 14 larger auxiliary camps were built along the wall, which were set up at regular intervals. The bulk of the Roman occupation troops were also in these . They could be brought quickly to any location in the Wallzone via the well-developed military road. If necessary, intervention troops could be withdrawn from the Corbridge / Halton Chesters Vindolanda and Carlisle / Stanwix fortifications to endangered sections of the wall without completely exposing the border there. At Stagshaw, the main route to the north, Dere Street , crossed the Wall. The so-called “Portgate”, a paved passage and checkpoint, stood here. The Romans used their tried and tested signaling system for communication between the individual bases. During the day, the guards would probably use mirrors or polished metal plates to transmit flashing signals from tower to tower, when it was cloudy or foggy, tubas or horns were used, and torches were used at night. The transmission of messages to quickly alert the border troops in the event of enemy attacks in order to be able to intercept the intruders by means of a pincer maneuver in the front border zone before they could cause major damage was one of the main tasks of the wall crew. This warning system was also common at the other limits of the empire.

Hadrian's Wall had a total of 80 gates over its entire length - secured by small fortifications, each at a distance of exactly one Roman mile, which, according to the current unit of measurement, corresponds to about 1470 to 1490 m. The cavalry fort protruded a little over the wall, with gates opening to the north. Although this seems contradictory, since they were supposed to keep the warring tribes out of the north, they were thereby an effective means of deterring any attacker, as they made a rapid failure of the cavalry possible. If it threatened to be cut off or surrounded, a quick retreat could be started again behind the safe walls. David Breeze explains the high number of gates primarily from the strategy that the Roman army of the time preferred to use: the Roman soldiers of the middle imperial era only seldom fought down from the protection of solid walls; they were in close formation for forward defense and field battles trained. This offensive approach was hindered by the wall. With the help of the many passages, the garrisons were able to react quickly and flexibly to approaching attackers or changing circumstances. The wall, closed from coast to coast, was still permeable, but only to the north. In theory, approaching enemies could be rendered harmless well in advance, even before they had even reached the border zone (provided they were discovered in time).

The wall itself was provided with additional small forts (mile forts) on the south side of the wall and within a third of a mile with two watchtowers at intervals of about one Roman mile. However, the distance between the towers often differs a little. Ditches were dug on the north and south sides as an obstacle to the approach, except where the wall ran past extremely sloping terrain, such as the volcanic folding of the Great Whin Sill (Northumberland National Park), thus rendering further excavation unnecessary. In front of the embankment raised when the trench was excavated, there were three rows of pits as an additional obstacle, which were presumably studded with pointed branches. In front of the wall section near Wallsend , some holes were found that had been made in Roman times, in which there were still remains of thorn bushes (cippi) . It probably also acted as an obstacle to the approach.

Seen from north to south, the defense system consisted of the following elements:

- the northern glacis with a ditch and camouflaged pitfalls, riddled with sharp wooden stakes and iron ankles (the so-called Lilia ),

- the wall itself,

- a military road and

- the southern ditch, vallum , between two earth dams.

Compared to the Upper German-Raetian Limes , Hadrian's Wall was a considerably stronger line of defense. The integration of already existing forts into the wall met with fierce resistance from the Caledonian tribes, who mainly farmed cattle, during the initial stage of the construction work, as it now divided their areas and thus probably also cut them off from the most fertile summer pastures in the south. It seemed to the Roman commanders also inexpedient to have to secure the entire construction site with considerable troop expenditure, which had its quarters in the relatively distant forts on the old Stanegate line. It is therefore easy to imagine that these two factors influenced the decision to build a light version of the wall instead of a solid version.

Wall

Such fortifications were called Murus caespiticius by the Romans - if it was a wall system built from turf - or vallum . The barrier wall, which was over 100 km long, was not only of different construction quality, but also consisted of different materials: The narrow foundation consisted of rubble stones that were only partially mortared or bound with clay. The base was of different heights, about three to four layers of stone. Above it rose a 4.5 m high, double-shell wall that clearly receded behind the foundation plinth. Whether the wall also had a battlements with battlements as chest protection is disputed. No scaffolding holes were detectable on the outside. Drainage ditches on the foundations were only added during later repairs. They were laid out at regular intervals of 2.4 m. For the first 72 km (Newcastle to Irthing) locally available types of stone were used. The quarry stones were lifted out of their position with the help of metal goblets wedged in wolf holes , split into several parts and then processed by the stonemasons into more manageable blocks. Stones inserted unprocessed testify to the pressure to finish the wall as quickly as possible. Quarries could be located on both sides of the wall by inscriptions. In order to avoid long transport routes, the lime was burned on site. Possibly it was plastered in the early days and provided with red grouting (so-called dummy masonry) that were supposed to simulate more massive stone blocks. Traces of such plastering have been archaeologically proven in some places on the original wall and also in other Limes forts. It is not certain whether the wall was plastered along its entire length. The wall was probably only continued after the fort had been completed. This could also explain its - in parts - late completion. The eastern part from Wallsend to the Irthing River was built in stone from the start. The western section, from Birdoswald to Bowness-on-Solway, was originally designed as an earth wall (murus cespiticius) , which was probably crowned with a wooden palisade as a parapet . It is also possible that the earth wall was built under Traian and that the building material used for fortifications at that time was used. For the 45 km long section between Irthing and Solway, only sod slabs were laid on a 2.4 m wide earth wall at the base. Perhaps too little stone material was available in the vicinity. The earth wall rose steeply on the north side and fell gently in the south. However, a lack of stone cannot be a satisfactory explanation for the construction of the western earth wall. For example, under Hadrian, the earth wall between MK 49 and WT 49A , which collapsed due to erosion, was closed by a stone wall. Until the late 2nd century under Septimius Severus, it was finally completely replaced by a stone wall (so-called narrow version 1.8 m wide).

Military road

On the south side of the wall was accompanied by a street leading from east to west, which, unlike the street on Antoninuswall, was only laid out during the major renovation work under Septimius Severus. It ran mostly between the wall and the south ditch, but deviated significantly from this line, especially at the mile forts or steep inclines. It was supposed to ensure a largely unobstructed connection between the forts and to facilitate replenishment. Express messages or orders could also be transmitted from coast to coast by messenger riders / runners within a short time and undisturbed. A good runner covered the distance between two towers in just 2.5 minutes. The route was between two and five meters wide. Because of the sometimes very steep terrain, it was not always passable for wagons. The Stanegate remained the most important road connection for long-distance traffic on the border line .

North ditch

In front of the approximately six meter wide berm ran a ditch eight to ten meters wide and three meters deep, with a V-shaped or pointed ditch. The excavation was heaped up on the enemy side to form an embankment that was only interrupted in front of the mile forts. Behind it earth dams made it possible to cross. The trench was supposed to prevent attackers from getting too close to the wall and from being fought with projectiles beforehand. The sharp angle at the bottom should break the ankles of anyone attempting to negotiate it. It did not run continuously, but was only excavated in sections. It was probably not considered necessary everywhere by the engineers. It is completely absent from the forts south of the Irthing. In research, the trench is seen as marking a safety area. According to a reinterpretation, however, it was actually intended to protect the border zone during the construction of the wall.

Particularly noteworthy is a 1.6 km long trench section, "Limestone Corner". It is located on Teppermoor Hill (Whin Sill Massif) near MK 30 . Its name is a bit misleading. In truth, the rock there does not consist exclusively of limestone, but largely of volcanic quartz dolerite (basalt) and fine-grain igneous rock. The Romans never completed the moat at this point. At one point only a small amount of topsoil was removed. There are still large stone blocks in the middle of the ditch and on its north side that could not be removed. On one of the boulders there were indications as to which method the legionary pioneers used to crush the rock for removal. To do this, holes were first drilled or carved into the quartz veins at the top of the rock. Wooden wedges were then driven in to split the rock along the quartz veins. The wooden wedges were probably also doused with water so that they swell and break the rock more quickly. It is unclear why the Romans stopped digging the trench here. Perhaps the rock became too hard at this point, the effort to crush it too big, or the workers were under too much time pressure that it was not considered necessary to finish it.

Südgraben

To the south of the wall ran - in contrast to other limits - next to the military road a continuous, shallow ditch (so-called vallum ) about six meters wide and up to three meters deep. The latter, however, is a modern name; the Romans probably called it fossatum . It was laid out at 122, was 112 km long and stretched from Newcastle in the east to Bowness-on-Solway in the west. With the excavation - set back approx. Nine meters from the edge of the trench - lower dams were raised on both sides. An estimated 1,465,313 m³ of earth was moved for this purpose. These were then usually covered with turf, and occasionally with stones. Direct access to the wall was only possible via 16 well-guarded causeways that were laid out near the larger forts. Usually the Vallum was near the wall. In contrast to some wall sections, however, it was laid out in very long, straight sections, extremely steep terrain was bypassed - if necessary also widely. In the topographically demanding, central wall section, where the wall stands hard on the cliff edge of the Whin Sill, the Vallum runs in the valley. Where it crosses very soft terrain, such as B. at White Moss in Cumbria, only the two earth dams were raised. Sometimes it was uninterrupted by causeways , especially at Portgate , at wall crossings like that of Benwell and perhaps at some heavily frequented mile forts. It is believed that it served as a marker for a 36-meter-wide military exclusion zone, in which troops could move quickly and unhindered by civilians on the east-west axis. Although this may have been its primary purpose, it was also an obstacle to the approach of enemies emerging behind the ramparts. By reducing the number of crossings, the Südgraben made it more difficult for riders and wagons to cross the border illegally and thus also improved the control of individuals or small groups. Presumably, the exclusion zone was only established after the wall was completed, as the moat leads around the fortifications built in Hadrian's time, such as Benwell and Birdoswald. It would also be possible that it should protect the construction site of Hadrian's Wall or the pastures of pack animals and cavalry horses. Another explanation would be that the Vallum was actually a preparation for a road that was never completed. The Vallum probably only fulfilled its function for a short time, probably less than ten years.

Castles

Originally only twelve forts were planned and built on the wall itself. The distance between them was generally seven Roman miles. A distance that could be covered on foot in one day. Two more stone forts were later added to the existing chain of fortresses (Carrawburgh and Drumburgh). Carvoran was rebuilt towards the end of Hadrian's government. It was on the old Stanegate line with Carlisle, Chesterholm and Corbridge.

The wall fort had the usual playing card-shaped floor plan for the time, but had some special features: The fort at Halton Chesters was extended by an annex in the Severan period. Four camps were built on the wall in such a way that they formed the northern barrier (Housesteads, Great Chesters, Drumburgh, Bowness). In five of the forts their praetentura protruded far beyond the wall (Birdoswald, Chesters, Halton Chesters, Rudchester, Benwell). With a few exceptions, only cavalrymen were stationed in them. Where there was a stone wall at the beginning, the stone forts were also raised. In the case of the camps on the wood-earth wall, the defense initially consisted of this material. Only the interior was made of stone. When the wall was rebuilt, the fort defenses were later replaced by stone walls.

The medieval castle was not a fortress in which the garrison could withstand long sieges. Rather, it was a lightly fortified barracks that should not be taken in one fell swoop. About 500 men were housed in it. Their main purpose was to keep a large number of soldiers ready at a strategically important location so that they could quickly take on invaders if necessary. The fortifications of the ramparts served as protection from the long-range weapons commonly used at the time, such as javelins, sling stones or arrows. They were surrounded by pointed trenches 5.4 to 5.9 meters wide and 2.66 to 2.96 meters deep. The walls were 1.2 to 1.5 meters wide and, at 3.6 to 4.4 meters, not particularly high. The battlements were protected by battlements. It was additionally reinforced by square towers set on the inside, which were erected at regular intervals. The corners of the fort were also secured by such towers. The battlements consisted of a raised ramp made of earth, rubble or peat and clay. He could be reached via a road that ran around the entire camp internally (via sagularis) . The ovens (clibani) , which had to be built far away from the other buildings due to the enormous fire hazard, were also included in it . The latrines (lavatrina) were also located on the ramp . They were always at the lowest point of the fort and were housed in long rectangular buildings. This position enabled constant rinsing with fresh water. The best-preserved latrine in Housesteads Fort had room for 16 men.

Access to the forts was possible through four gates with two passages each, flanked on each side by towers with guard rooms. The gates at Housesteads and Birdoswald are typical examples. Its portals were vaulted and could be closed with two gate leaves, the pins of which turned in iron-coated stone sockets between the central pillar and the side walls of the gate structures. If the praetendura protruded beyond the wall, three of them were placed to the north of it to enable the riders to make a quick dropout. The cavalry fort had smaller side gates in the east and west, through which the military road ran and which formed the rear main road (via quintana) . Since these gates were protected by the wall, all through traffic was probably handled through them. They only had one passage and no guard rooms of their own. Such gates can be found u. a. in Chesters and Birdoswald. In those forts where the wall itself formed the north wall, it was only broken through by a gate.

The main streets of the camp led directly to the main buildings. The interior of the forts was divided into three functional areas: center (latera praetori) , front camp (praetentura) and rear camp (retendura) . The standard buildings of a wall fort were the camp administration ( principia ), the commandant's house ( praetorium ) , the warehouse ( horreum ) , the hospital ( valetudinarium ) , workshops (fabricia) , functional buildings (bakeries, latrines) and barracks / stables (centuriae / stabuli) . Some rooms of the camp administration and the commandant's house were richly painted and z. Some have underfloor heating, bathrooms and latrines.

| Wall fort | Closest place |

| Maia (replenishment center) | Bowness-on-Solway |

| Congavata | Drumburgh |

| Aballava | Burgh-by-Sands |

| Uxelodunum / Petrianis (headquarters) | Stanwix |

| Camboglanna ? | Castlesteads |

| Banna ? (Training centre) | Birdoswald |

| Magnis | Carvoran |

| Aesica | Great Chesters |

| Vercovicium | Housesteads |

| Brocolitia | Carrawburgh |

| Cilurnum | Chester |

| Onnum | Haltonchesters |

| Vindobala | Rudchesters |

| Condercum ? | Benwell |

| Pons Aelius | Newcastle upon Tyne |

| Segedunum | Wallsend |

Five forts (Birrens and Netherby were also supposed to secure the tribal area of the allied brigands ) and were located north of Hadrian's Wall as apron protection. The last coin from one of these outposts found by archaeologists was minted around 309. The outpost forts were probably abandoned under Constantine I, approx. 312-314:

| Outpost fort | Closest place |

| Blatobulgium | Birrens |

| Castra Exploratorum (training center) | Netherby |

| Fanum Cocidi | Bewcastle |

| Habitancum | Risingham |

| Bremenium | High Rochester |

Mile Fort

The mile fort covered an area of approx. 270 m² and was integrated into the wall on its north side. They had two passages in the south and in the north, with the north being additionally secured by a tower. Most of them were built in stone from the start - with the exception of the specimens on the wood-earth wall, which were originally made of brick as well. They were routinely placed one Roman mile apart regardless of the terrain. As standard, they had one or two elongated buildings made of wood or stone for internal structures. They served as depot and accommodation for eight to 32 men. Ovens were usually located in the north-west corner, while a staircase in the north-east corner provided access to the battlements and the northern gate tower. The architectural style of these fortifications varied slightly from region to region. They are differentiated on the basis of the design of their passages or on the basis of the dimensions of their main axes (between north and south gate) and are known as long axis type and short axis type (I to IV). At the end of the 2nd century, most of the northern passages of the mile fort were walled up. The rest of them were narrowed so that they could only be passed on foot.

Small fort

The barriers went beyond the western terminus of Hadrian's Wall in Bowness-on-Solway, which presumably extended from Bowness to Maryport and perhaps a little further. The west coast of Cumbria was secured by six stone forts (see table) and a chain of small forts about a Roman mile apart. They also had two gates and were exclusively earth and wood constructions; their floor plan was very similar to the mile forts on the wall. Most of them appear to have been manned by soldiers only from 122–140 AD.

| Coastal fort (Cumbria) | Closest place |

| Bibra | Beckfoot |

| Alauna (headquarters) | Maryport |

| Magis | Burrow Walls |

| Gabrosis | Moresby |

| Tunnocelum | Calder Bridge |

| Glannoventa | Ravenglass |

Watchtowers

Between each mile fort there were two towers, about six square meters in size and with a square floor plan, evenly spaced. They were erected at the same time as the wall and were built in stone, including the specimens along the peat wall. They offered space for a temporary occupation by about eight soldiers. They were almost certainly higher than the wall (up to nine meters, estimated). They served as observation posts and for the transmission of light or smoke signals. Each tower was within sight of the neighboring MKs, which enabled mutual protection and - when fully occupied - comprehensive surveillance of the border. The entrance was on the south wall. In the middle of the first floor was a fireplace that was used for heating and cooking. Access to the upper floor and the battlement was probably via a simple wooden ladder inside the building. The appearance of the upper floor (battlements or a tiled roof) is still unclear due to the lack of archaeological evidence. On the coast of Cumbria, a number of signal towers were later added to the chain of castles there in order to prevent an enemy landing from the sea.

Wall bridges

At Willowford, Chesters and Carlisle / Stanwix the rivers Tyne (Tinea) , Irthing and Eden were spanned by ramparts. From these, the multi-phase bridge at Chesters can be reconstructed particularly well. In the 2nd century only a simple and narrow stone arch bridge led across the river. At each end there was an abutment that tapered to a point on the river side. The widths of the bridge and wall were almost identical, which suggests that they were built at the same time. Also proof of the existence of a battlement on the top of the wall. It is possible that the bridge was destroyed by flooding and replaced in the early 3rd century by a nine-meter-high and 61-meter-long four-arch construction with a wider driveway. It was to be entered from the bank via a twelve meter wide ramp. The masonry of the bridge arches was made using the opus quadratum technique . At both ends there was a gate tower directly above the abutment, the stone railings were decorated with columns and statues, which also contained small shrines.

At Willowford, the three-arched stone bridge built in Hadrian's time connected the western section of the earth wall with the eastern end of the stone wall. It went through three construction phases and was also equipped with watchtowers at both ends. The abutment has also been preserved on its east side to this day. This bridge and two others at Stanwix and Corbridge have shown major renovations for the late 3rd century. They were probably carried out in the course of preparations for the campaign of Septimius Severus in northern Britain.

There were three other bridges in the vicinity of the wall. The first was at the Pons Aelius fort . It was the only bridge outside of Rome that was named after an emperor, which underlines its special importance for road traffic on Hadrian's Wall. The deck slab and main girder were probably made of wood, only the pillars and abutments are likely to have been made entirely of stone. It was built before the fort (122) and was probably in use until 1248. At Stanwix there was a stone bridge over the Eden and the Caldew. Another was west of Corbridge, where Dere Street crossed the Tyne. The remains of the southern bridge abutment can be seen when the water level is low. During excavations, stones of their access ramp were uncovered. There is also evidence of a Roman bridge further downstream at Bywell which linked Ebchester and Halton east of Postgate.

Detailed descriptions in:

Wall gates and ditch crossings

At some important and heavily frequented border crossing points, separate gates were built due to their location or topographical conditions. They were outside or near the forts. So far, three such goals are known. They were on Dere Street ( Portgate ) and at Housesteads Fort (Walltor on Knag Burn ). The latter were passages that could be closed on both sides and were comparable to today's security gates, in a way, a small-scale mile fort. At the same time, such a surprise attack or breakthrough by attackers from the north was impossible. The crossing over the southern ditch at Fort Benwell was an exception . It only consisted of a stone embankment spanned by an arch construction. It was closed with wooden gate wings that could only be opened from the side facing the fort. The Benwell moat was probably not the only one of its kind on the wall. Such stone dams have also been seen south of the castles at Housesteads, Great Chesters, and Birdoswald.

Camp villages

In the course of time, extensive civilian settlements often developed around the fortifications, which the Romans called Vici . A vicus was at the lowest level of the self-governing settlements recognized as such under Roman law. They served to supply the troops stationed at the wall, to administer the land and as trading centers for the local population. The presence and purchasing power of a large number of regularly paid soldiers attracted many people from all parts of the empire. Many of the residents are likely to have been relatives of the soldiers stationed at the wall. Geophysical studies have shown that civil settlements were many times larger than the camps next to which they were founded, although the structures recorded in this way cannot be dated. The buildings extended along the fortifications of camps and their arteries. Some settlements were also framed by earth walls and ditches, but it is unclear whether these were used for defense. It is believed that the soldiers' wives and families lived here rather than in the forts. Around their houses there were shops, workshops, inns, temples and brothels. Somewhat away from the camp and the civilian settlement were the cemeteries for soldiers and civilians. Little is known of these on Hadrian's Wall. Most burials were preceded by cremation, although body burials became more common from the third century onwards. Although it was not allowed until the third century that soldiers on active duty could officially marry. The soldiers stationed on the wall mostly came from distant provinces of the empire. Only a small percentage returned to their original homeland after having started families with local women. After leaving the army, in addition to an advance payment, they were also given a piece of land in the immediate vicinity of their last stationing location, which they could cultivate for their own use. This helped develop the local economy and increase political stability. In times of war these men also provided the reserve to defend the border (veterani) . Numerous traders and craftsmen ran their shops and workshops in the villages and supplied soldiers and civilians with everyday necessities. The most common building type found in these settlements, as well as in the areas around Hadrian's Wall, were the long and narrow strip houses . These appear to have been used for domestic and commercial purposes. The Vici also had bathhouses (ballineum) and hostels (mansio) for travelers in some cases .

Supply routes

The wall was supplied with supplies via a well-developed network of supply roads. The camps and civil settlements were connected by roads along which milestones were erected. Two of the locations used as the starting point for distance measurements were Carlisle in the west of the Wallzone and Corbridge in the east of the Wallzone. To the west a road led to the port of Ravenglass (Glannoventa) and Kirkbride to Bowness (Maia) . From Catterick (Cataractonium) , the goods could be transported on Ermine Street to the northern border. The supply at the eastern end of the wall could be done via Ermine Street to York (Eburacum) and Chester-le-Street on Wrekendike to South Shields (Arbeia) , at the mouth of the Tyne. From there a road led to Wallsend (Segedunum) . At Newcastle upon Tyne (Pons Aelius) with its bridge over the Tyne, a road led south to the supply center of Corbridge (Coriosopidum) and the Stanegate to the west. From Corbridge, Dere Street led north via Halton Chesters / Portgate (Onnum) to the Antonine Wall.

Antique souvenirs from Hadrian's Wall

In the 18th, 20th and 21st centuries, three pan-like vessels were found that were probably used for scooping wine. On them are the names of some of the camps on Hadrian's Wall. The three vessels described below ( paterae or trulla ) probably date from the period between the second and third centuries AD and were probably souvenirs from soldiers stationed on the wall when they returned to their homeland. They are an important source for the names and positions of the western forts in the fortress chain of the ramparts.

Rudge Cup