Henderson (Pitcairn Islands)

| Henderson Island | |

|---|---|

| Map of Henderson | |

| Waters | Pacific Ocean |

| Archipelago | Pitcairn Islands |

| Geographical location | 24 ° 22 ′ 42 ″ S , 128 ° 19 ′ 30 ″ W |

| length | 10 km |

| width | 5 km |

| surface | 43.1 km² |

| Highest elevation | 33.5 m |

| Residents | uninhabited |

| Location of Henderson within the Pitcairn Islands | |

| Henderson | |

|---|---|

|

UNESCO world heritage |

|

|

|

| The north beach on Henderson |

|

| National territory: |

|

| Type: | nature |

| Criteria : | vii, x |

| Reference No .: | 487 |

| UNESCO region : | Europe and North America |

| History of enrollment | |

| Enrollment: | 1988 (session 12) |

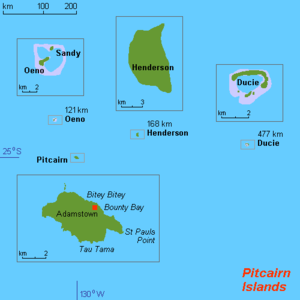

Henderson , historically San Juan Bautista (São João Batista) or Elizabeth, is a coral island in the southeast Pacific that belongs to the Pitcairn Islands . The uninhabited island with a length of ten kilometers, a width of five kilometers and an area of 43.1 km² is a UNESCO World Heritage Site .

geology

Henderson is an upscale atoll . Originally, the island was - like many in the South Pacific - a classic atoll , i. H. a ring of coral islands that had formed around a central mountain of volcanic origin that was formed around 13 million years ago and has since sunk in the sea. Further volcanic activity, which led to the formation of Pitcairn Island 900,000 years ago , deformed the earth's crust in such a way that the Henderson Atoll was raised even further above the sea surface. This led to the emergence of the table mountain-like plateau characteristic of Henderson . The uplift process continues today at a rate of 0.1 mm per year. The plateau slopes slightly from north to south. The highest point was measured in the north at 33.5 m . In the northern third of the island, the plateau deepens in an area from two to four kilometers to 15 meters above sea level, the silted up remnant of the former lagoon. The interior of the island consists of porous limestone of the late Tertiary and is heavily karstified. The karst and sharp-edged, weathered coral tips make it almost impossible to cross Henderson. Within a very short geological time, a new coral fringe has formed around the island.

There is no open fresh water on Henderson. Groundwater seeps out in sparse amounts only on the north beach. However, the infiltration point is below sea level and can only be reached at low tide . There are also a few drip sites in the caves on the north beach that were used by the Polynesian inhabitants.

Flora and fauna

Henderson is a nature reserve since 1988 and is part of World Heritage of UNESCO .

flora

A 1991 inventory of the flora by Steve Waldgren and Naomi Kingston of Trinity College Botanic Garden in Dublin revealed the number of 63 species, nine of which are endemic .

The beach zones are densely overgrown with bushes and creeping plants above the tidal areas, on the north and west beaches often interspersed with coconut palms and pandanus trees .

Behind it rises the up to 30 meters high, karst plateau made of porous limestone , into which the rainwater quickly seeps away. The flora of the plateau is dominated by the bushy growing tree Pisonia grandis , which in part forms extensive thickets, which are interspersed with pandanus in places. Another common plant on the plateau is the small tree Nesoluma st.-johnianum , which belongs to the sapote family . The endemic bush Santalum insulare hendersonense , belonging to the sandalwood family, grows as undergrowth , but it also occurs in the higher beach and lower cliff areas. In the crevices of the karst, but also in the lighter areas of the Pisonia forest, the epilithic , also endemic plant Peperomia hendersonensis , which belongs to the pepper family , grows .

fauna

Like the flora, the fauna of Henderson is also unique, although - due to its isolated location at the extreme end of the biogeographical region of the Indo-West Pacific - relatively underdeveloped. The land fauna of the Pitcairn Islands is oriented to the west; H. the species originally come from the west pacific region and came to Henderson by using the islands further west as "stepping stones" for their distribution.

Almost all animals found on land are indigenous or endemic , which makes Henderson a unique research space for biologists . There are no larger land animals on Henderson.

Birds

Henderson is the breeding ground for numerous bird species. Seventeen species of seabird are cataloged, including the fairy tern ( Gygis alba ), the banded frigate bird ( Fregata minor ), which nests in abundance in the Pisonia forest of the plateau, the curlew Numenius tahitiensis , the Noddise tern ( Anous stolidus ) and the red-footed booby ( Sula sula ).

Four of the land birds found are endemic:

- Tuamotus moorhen ( Porzana atra ), also Henderson's rail, a black-gray, flightless ground-breeder of about 25 cm in length.

- Henderson fruit pigeon ( Ptilinopus insularis ), also silver-cheeked downy pigeon - which feeds on fruit pulp and insects. The plumage of the colorful bird was used as jewelry by the Polynesian natives of Henderson and exported to other islands ( Mangareva ).

- Hendersonlori ( Vini stepheni ) - a small, highly specialized parrot bird from the genus Maidloris , which feeds mainly on the nectar of two plants ( Scaevola sericea and Timonius polygamus ), but also occasionally consumes pollen , fruit pulp and insects as complementary food .

- Henderson reed warbler ( Acrocephalus taiti ), also Pitcairn reed warbler , a small bird belonging to the genus of reed warbler .

In 1994, Wragg and Weisler named four more, now extinct, land bird species, including the Henderson pigeon ( Gallicolumba leonpascoi ).

Reptiles

The reptiles on the island include a skink ( Emoia cyanura ), a gecko that has not yet been precisely identified and the green sea turtle ( Chelonia mydas ).

insects

Quite a few insect species occur exclusively on Henderson, including two beetles ( Coleoptera ). Two species of jumping horror that were recorded in the 1991 inventory had not previously been observed anywhere. Of the six species of constant winged ( Homoptera ) registered on Henderson , two were endemic and one was previously completely unknown. In Henderson, there are 36 species of Diptera ( Diptera ), including three endemic. There are also 53 species of butterflies ( Lepidoptera ).

Mollusks

Half of the 16 species of land snail found on Henderson are endemic.

Mammals

In general, the population of mammals in the Polynesian Islands is low, usually they were introduced by humans. There is no indigenous species on Henderson . The Pacific rat ( Rattus exulans ) is the only mammal that has so far been safely identified on Henderson. It was brought in by Polynesian settlers who took it with them as a food animal. In August 2011, the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds tried to exterminate the rats with 75 tons of poisonous bait. The attempt failed, about 60 to 80 rats survived. The population rose again shortly afterwards to an estimated 50,000 to 100,000.

Marine fauna

The beaches of the island, especially the north beach, are visited by the green sea turtle ( Chelonia mydas ) to lay their eggs. As archaeological findings prove, the species was an important source of food for the Polynesian natives.

Henderson is completely enclosed by a coral reef that has only two narrow passages in the north and south. The underwater fauna was also able to develop undisturbed on Henderson. In 1987 there was a scientific inventory of the corals , 29 different species were registered. The molluscs ( Mollusca ) are particularly rich in species with 320 species. There are numerous sperm whales in the surrounding waters, and the Pacific between the Marquesas and the Pitcairn Islands was a preferred destination for whalers in the 19th century .

history

Archaeological finds show that Henderson was temporarily inhabited by Polynesians . The population is unlikely to have included more than a few dozen people. The findings date the settlement to the period between 1050 (or perhaps earlier) and 1600 AD. The archaeologist Marshall Weisler of the University of Otago in New Zealand has established trade links between Mangareva , Pitcairn and Henderson in the course of recent research . His research shows the export of oyster shells for making jewelry and fishhooks from Mangareva to Pitcairn and Henderson on the one hand and the import of stone tools from Pitcairn and probably bird feathers and sea turtles from Henderson on the other. The densely populated Mangareva may have been the hub for this triangular trade, which also included the Tuamotu and Austral Islands . The trade relations ended around 1450, the reasons for this can no longer be determined. The evolutionary biologist Jared Diamond suspects in his book Collapse a man-made ecological catastrophe on Mangareva as the cause; Weisler and Walter cite social tensions caused by overpopulation and lack of resources as reasons. The now self-reliant populations of Pitcairn and Henderson probably survived for a few more generations. Henderson was abandoned around 1600. When the island was first visited by Europeans, it was already uninhabited.

The Portuguese navigator in the Spanish service Pedro Fernández de Quirós discovered the island for Europe on January 29, 1606 . He named it "San Juan Bautista" after Saint John the Baptist and dedicated only a few lines to it in his report:

“This country is believed to be 870 iguanas from Lima. It has a circumference of 10 iguanas. It is massive, open, of moderate height and has groups of trees on a plateau. It is also steep and its beaches are rocky. It is only inhabited by birds. The latitude is 24 ° 45 ′ and we named it 'San Juan Bautista'. Since [the island] has no harbor where we could take wood and water, we continued our journey WNW. "

The island was soon forgotten again. On January 17, 1819, she was rediscovered by James Henderson, the captain of the merchant ship Hercules of the British East India Company, and received her current name. Just six weeks later, on March 1, 1819, the British whaler Elizabeth reached Henderson Island under the command of Captain Henry King. Since King knew nothing of the Hercules' previous visit , he named the island "Elizabeth" after his ship.

The shipwrecked people of the American whaler Essex from Nantucket landed on Henderson after their ship was rammed by a sperm whale about 3000 kilometers north and sank in 1820 . They found the island uninhabitable and continued to sail towards South America in their open boats . After driving 7,000 kilometers, five survivors were rescued. The three crew members who remained on Henderson were found alive by the British ship Surry in 1821 after spending more than four months on the inhospitable island. The later published diary of Owen Chase , an Essex crew member , was the model for Herman Melville's famous novel Moby Dick .

A curious story, the veracity of which is controversial, happened during the Second World War . In 1937 the British-New Zealand light cruiser HMNZS Leander visited the islands of Oeno, Ducie and Henderson. In order to renew the claim of the British crown, the Union Jack was hoisted on Henderson and a plaque was left with the inscription: “This island belongs to SM King George VI. She was visited by HMS Leander on August 6, 1937. Signed: JW Rivett-Carnac, Captain RN “When Henderson was visited again in December 1940, the British flag was replaced by the swastika flag . A plaque was found on the beach with the inscription: "With the best recommendations to King George VI, this island is now the property of the Greater German Empire." Who left the plaque and flag has not yet been clarified. Henderson was called at by the German auxiliary cruiser Atlantis , but this only happened in October 1941.

In the 1980s, the American cattle baron, banker, mine and landowner Arthur M. (Smiley) Ratliff (born June 18, 1924 in Grundy, Virginia , † October 31, 2007 in Kingsport, Tennessee ) intended to found his own nation on Henderson and establish an airfield, settlement and livestock farm. The nomination for UNESCO World Heritage in April 1988 prevented the implementation of these plans.

The island is still uninhabited. Occasionally looking Pitcairner on the north beach to where the of them so-called Miro-wood ( Thespesia populnea Thespesia populnea ) and tau wood ( Cordia subcordata , genus Kordien to win) for their carvings. Henderson is off all shipping routes and is therefore hardly accessible for tourists. The island may not be entered without prior official permission.

environmental pollution

Despite its very remote location, Henderson is now also affected by global pollution. Ocean eddies that accumulate civilization litter bring litter to Henderson, which is spread across the beach. The main components are plastic parts of all kinds, including fishing waste (nets, ropes, floats) and plastic bags. According to a 2017 study, an estimated 37.7 million pieces of garbage with a total weight of 17.6 tons had washed up by then. Another expedition in 2019 confirmed the progressive pollution. Six tons of plastic waste were collected.

Web links

- Entry on the UNESCO World Heritage Center website ( English and French ).

- Map of the island

- Private Henderson Island Homepage (in English)

- Satellite image of Henderson ( December 23, 2010 memento on the Internet Archive ) (north is on the right in the photo)

Individual evidence

- ^ Robert Irving, Terry Dawson: The Marine Environment of the Pitcairn Islands . A report to Global Ocean Legacy, a project of the Pew Environment Group . Dundee University Press, Dundee 2012, ISBN 978-1-84586-161-2 , 3.2 Henderson - Key Facts, pp. 21 (English, pewtrusts.org [PDF; 3.6 MB ; accessed on May 19, 2020]).

- ^ A b c Robert Irving, Terry Dawson: The Marine Environment of the Pitcairn Islands . A report to Global Ocean Legacy, a project of the Pew Environment Group . Dundee University Press, Dundee 2012, ISBN 978-1-84586-161-2 , 1.3 Geology / geomorphology, pp. 4 (English, pewtrusts.org [PDF; 3.6 MB ; accessed on May 19, 2020]).

- ↑ a b c Dana Procter & LV Fleming (Eds.): Biodiversity: the UK Overseas Territories, Chapter 12: The Pitcairn Islands, Joint Nature Conservation Committee, Peterborough (Cambridgeshire) 1999, ISBN 1-86107-502-2 , pp. 88–95 digitized version (PDF; 66 kB).

- ^ J. Florence, S. Waldren, AJ Chepstow-Lusty: The flora of the Pitcairn Islands: a review. In: Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. Vol. 56, No. 1/2, 1995, ISSN 0024-4066 , pp. 79-119, doi: 10.1111 / j.1095-8312.1995.tb01079.x .

- ↑ Markus Kappeler: Tuamotu marsh grouse - Henderson Lorikeet - silver-cheeked downy pigeon - Pitcairn reed warbler .

- ↑ Michael De L. Brooke & Peter J. Jones: The diet of the Henderson Fruit-dove Ptilinopus insularis. I. Field observations of fruit choice. In: Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, Volume 56 (1-2), September 1995, pp. 149-165.

- ^ Marshall I. Weisler: An Archaeological Survey of Mangareva. Implications for regional Settlement Models and Interaction Studies. In: Man and Culture in Oceania. Vol. 12, 1996, ISSN 0911-3533 , pp. 61-85.

- ↑ Rosie Trevelyana: The feeding ecology of Stephen's lory and nectar availability in its food plants. In: Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. Vol. 56, No. 1/2, 1995, pp. 185-197, doi: 10.1111 / j.1095-8312.1995.tb01084.x .

- ^ Trevor H. Worthy, Graham M. Wragg: A new species of Gallicolumba: Columbidae from Henderson Island, Pitcairn Group. In: Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand. Vol. 33, No. 4, ISSN 0303-6758 , 2003, pp. 769-793, doi: 10.1080 / 03014223.2003.9517758 .

- ^ TG Benton: Biodiversity and biogeography of Henderson Island's insects. In: Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. Vol. 56, No. 1/2, 1995, pp. 245-259, here p. 247, doi: 10.1111 / j.1095-8312.1995.tb01089.x .

- ↑ Süddeutsche Zeitung, How Rats Survived Extinction on Henderson Island , April 20, 2016 .

- ^ Marshall I. Weisler: Henderson Island prehistory: colonization and extinction on a remote Polynesian island . In: Biological Journal of the Linnean Society . tape 56 , no. 1-2 , September 1995, ISSN 0024-4066 , pp. 377-404 , here pp. 388-390: Chronology , doi : 10.1111 / j.1095-8312.1995.tb01099.x (English).

- ↑ Guillaume Molle, Aymeric Hermann: Pitcairn before the Mutineers: Revisiting the Isolation of a Polynesian Island . In: Sylvie Largeaud-Ortega (Ed.): The Bounty from the Beach. Cross-Cultural and Cross-Disciplinary Essays . ANU Press, Acton, Australia 2018, ISBN 978-1-76046-244-4 , chap. 2 , p. 67–94 , here pp. 71–74: The settlement of Pitcairn , doi : 10.22459 / BB.10.2018.02 (English).

- ^ Marshall I. Weisler: Henderson Island prehistory: colonization and extinction on a remote Polynesian island . In: Biological Journal of the Linnean Society . tape 56 , no. 1-2 , September 1995, ISSN 0024-4066 , pp. 377–404 , here p. 399–401: Long-distance Interaction , doi : 10.1111 / j.1095-8312.1995.tb01099.x (English).

- ↑ Guillaume Molle, Aymeric Hermann: Pitcairn before the Mutineers: Revisiting the Isolation of a Polynesian Island . In: Sylvie Largeaud-Ortega (Ed.): The Bounty from the Beach. Cross-Cultural and Cross-Disciplinary Essays . ANU Press, Acton, Australia 2018, ISBN 978-1-76046-244-4 , chap. 2 , p. 67–94 , here pp. 85–88: Tracing ancient inter-island mobility and exchange in south-east Polynesia , doi : 10.22459 / BB.10.2018.02 (English).

- ^ Marshal Weisler, Richard Walter: East Polynesian connectivity . In: Tamar Hodos et al. (Ed.): The Routledge Handbook of Archeology and Globalization . Routledge, Abingdon / New York 2017, ISBN 978-0-415-84130-6 , chap. 4.7, p. 369–386 , here pp. 376–379: The Mangareva-Pitcairn group: sustainability only with connectivity (English, limited preview in the Google book search).

- ↑ Guillaume Molle, Aymeric Hermann: Pitcairn before the Mutineers: Revisiting the Isolation of a Polynesian Island . In: Sylvie Largeaud-Ortega (Ed.): The Bounty from the Beach. Cross-Cultural and Cross-Disciplinary Essays . ANU Press, Acton, Australia 2018, ISBN 978-1-76046-244-4 , chap. 2 , p. 67–94 , here pp. 88–91: The abandonment of Pitcairn: Why, when and how? , doi : 10.22459 / BB.10.2018.02 (English).

- ↑ Quoted from: Clements Markham (Ed.): The voyages of Pedro Fernandez de Quiros, 1595 to 1606 . tape 1 . The Hakluyt Society, London 1904, III. Narrative of the Voyage of Pedro Fernandez de Quiros in 1606, for the Discovery of the Austrial Regions - Chapter VI, p. 192–193 (English, full text ).

- ↑ Thomas Farel Heffernan: Stove by a Whale - Owen Chase and the Essex . Wesleyan University Press, Middletown, CT 1990, ISBN 0-8195-6244-0 , Chapter Three: Ne Cede Malis , pp. 77–118 , here p. 80 (English, limited preview in Google book search).

- ^ Herbert Ford: Pitcairn Island as a Port of Call - A Record, 1790-2010 . 2nd Edition. McFarland & Company, Jefferson, NC 2012, ISBN 978-0-7864-6604-7 , Pitcairn: Port of Call - 1819, pp. 10 (English, limited preview in Google Book Search).

- ↑ Art. XXII: Extract from the journal of Captain Henry King of the Elizabeth . In: David Brewster , Robert Jameson (Eds.): The Edinburgh Philosophical Journal . Vol. III, No. VI , October 1820, ZDB -ID 218162-9 , p. 380–388 , here pp. 381–382 (English, full text ).

- ^ Name according to NW Faircloth: New Zealanders in the Battle of Britain (= New Zealand in the Second World War. Official History ). Department of Internal Affairs - War History Branch, Wellington 1950, p. 32 ( New Zealand Electronic Text Center: Biographical Notes ).

- ^ Herbert Ford: Pitcairn Island as a Port of Call: A Record, 1790-2010. 2nd ed., McFarland, Jefferson 2012, ISBN 978-0-7864-6604-7 , p. 152.

- ↑ James Serpell: Desert Island Risk. In: New Scientist. Vol. 98 = No. 1356, May 5, 1983, ISSN 0262-4079 , p. 320.

- ↑ World Heritage Nomination - IUCN Summary 487: Henderson Island (United Kingdom), PDF .

- ↑ Jennifer L. Lavers, Alexander L. Bond: Exceptional and rapid accumulation of anthropogenic debris on one of the world's most remote and pristine islands . In: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America . April 7, 2017, doi : 10.1073 / pnas.1619818114 (English).

- ↑ AFP : Plastic junk spawns desert island disaster in Pacific. (English) July 30, 2019, accessed July 30, 2019.

- ↑ Plastic: the island is over-littered. In: schweizerbauer.ch . July 31, 2019, accessed July 31, 2019 .