Plastic waste in the oceans

Plastic waste in the oceans comprises the remnants of plastic products that collect in the world's oceans and are then accumulated in various places. According to a study published in the scientific journal Science in early 2015 , around 8 million tons of this garbage ended up in the oceans in 2010 , with a confidence interval of 4.8 to 12.7 million tons per year.

The plastic waste consists of plastic parts , "primary" microplastics and the corresponding decomposition products ("secondary" microplastics). In particular, the constituents accumulate in some ocean drift current eddies and lead to considerable compression in some ocean regions; the North Pacific Gyre ( English North Pacific Gyre ) this phenomenon brought the nickname Great Pacific Garbage Patch (German Great Pacific Garbage carpet , first described in 1997) a.

In mid-2014 it was reported that geologists on the coast of the island of Hawaii had discovered structures made of molten plastics, volcanic rock, coral fragments and grains of sand, which they called a separate type of " rock ", as " plastiglomerate " due to their strength . In the meantime, the plastic crust has also been discovered in Italy on the island of Giglio . Plastic deposits in rock are also observed in the so-called beach rock .

Plastic rubbish floating in the oceans is permanently crushed by wave motion and UV light , whereby an ever higher degree of fineness can be achieved up to pulverization. With a high degree of fineness, the plastic powder is ingested by various marine life as well as by plankton instead of or with the usual food. Starting with the plankton, the plastic particles, to which toxic and cancer-causing chemicals such as DDT and polychlorinated biphenyls can adhere, continue to rise in the food chain . In this way, the plastic waste with the accumulating toxins also ends up in food intended for human consumption. In the 1980s, scientists still assumed that the plastic particles were no longer environmentally relevant, as they were colonized by algae and microorganisms , similar to floating seaweed plants .

In 2012, the scientific journal Environmental Science & Technology reported on a study on many beaches on all six continents, which found microplastic particles everywhere; This also includes fibers from fleece and other items of clothing made from synthetic materials: up to 1900 tiny plastic particles were found in the waste water from washing machines per wash cycle .

"Every little piece of plastic manufactured in the past 50 years that made it into the ocean is still out there somewhere."

"Every little piece of plastic that has been made in the past 50 years and ended up in the ocean is still out there somewhere."

background

A study commissioned by the World Economic Forum in 2016 describes the plastics economy as an archetypal linear economy in which, in contrast to an ideal circular economy, only 2 percent of annual production is recycled with the same quality. Another eight percent are recycled in a cascade, i.e. at a lower level. On the other hand, a share of 32 percent of plastic packaging worldwide is neither deposited nor incinerated, but leaves the system uncontrolled.

Extent, affected areas, density and amount

According to information from the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and scientists from the Sea Education Association (SEA), there has long been no precise estimate of the size of the areas contaminated by plastic waste; the whereabouts of 99% of plastic waste in the oceans remains unexplained, according to researchers.

According to information from the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) from 2005, an average of up to 13,000 plastic particles were floating on every square kilometer (km²) of ocean at that time . However, NOAA points out that UNEP does not cite any scientific source for this information.

A study conducted by the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC) has calculated, based on an expedition lasting several months (2010/2011) and sampling at over 300 locations in the world's oceans, that 88% of the world's ocean surfaces are polluted with microplastics.

According to the German Federal Environment Agency, there were 100 to 150 million tons of waste in the oceans in 2013 , 60% of which was plastic. 70% of the litter sinks to the ocean floor, 15% floats on the surface and 15% was washed up on beaches. On photographs of the Arctic deep sea floor between Spitsbergen and Greenland, extrapolated “83 pieces of garbage per soccer field ” were found; In 2010, after ten years at a depth of 2500 meters, the amount of submerged plastic waste doubled.

The Alfred Wegener Institute cites an annual entry of 4.8 to 12.7 million tons, calculated on the basis of production rates and the waste generated on land.

At the end of 2014, an international research group reported in the specialist magazine PLOS ONE after evaluating numbers from 24 studies with over 1,500 individual data collections, including for the first time also for plastic parts> 5 mm, that in the oceans, the five subtropical ocean eddies, in the busy coastal areas of Australia , in The Gulf of Bengal and the Mediterranean Sea contained more than 269,000 tonnes and more than 5.25 trillion pieces of plastic waste. The smallest particles would have been found near the North Pole .

According to a science study from the beginning of 2015, the result of the calculated input of an estimated average of around eight million tons per year corresponds to "five supermarket bags full of plastic per 30 centimeters of coastline", according to a report by the UN Environment Program (UNEP) from the end of 2014 Every year around 6.4 million tons of plastic waste enter the oceans.

Calculations by German hydrologists published in mid-October 2017 indicate a quantity of between 400,000 and a maximum of four million tons for the annual plastic cargo transported to the oceans.

In a study published in 2018, with ice samples from 2014 and 2015, between 33 and 75,143 microplastic particles were found per liter of sea ice .

According to a study published in 2020 by the Leibniz Center for Tropical Marine Research (as of August 2020) there are around 399,000 tons of plastic on the surface of the oceans alone .

Arctic

In the summer of 2013, an average of 63,000 plastic particles per km² of water surface were found off the west coast of Greenland and in the Barents Sea , mainly remains of plastic film from bags and packaging material. The amount found is around 30% higher than that in the known large garbage whirlpools in the subtropical Pacific or Atlantic . Obviously, the plastic parts do not sink to the ground as quickly as the salty surface water in the pull of the thermohaline circulation : the Barents Sea seems to form a kind of “ dead end ” for the garbage particles.

According to a report from the Alfred Wegener Institute (AWI) published online in October 2015 in the magazine Polar Biology , plastic waste is already on the surface of the water in the Arctic (North Pole). The origin is unclear; corresponding data was collected for the first time during an expedition in 2012 between Greenland and the Svalbard archipelago to the east .

High concentrations of microplastics were found in ice cores from the Arctic sea ice . Samples from Framstrasse contained up to several million plastic particles per cubic meter of ice, mainly polyethylene . The entry occurs primarily via tributaries, including the Bering Strait , the Mackenzie River and the Lena . Local sources also play a role in plastic pollution, such as shipping. Some of the plastic is transported with the drift ice through the Fram Strait into the Atlantic Ocean.

Atlantic

At the beginning of 2016, after more than six months of measurements at 18 locations in the ocean off New York City on the east coast of the United States, 165 million plastic parts were extrapolated (or more than 250,000 parts per km²) - 85% with a size of less than five Millimeters. In 2020 measurements showed that the plastic content in the Atlantic is much higher than previously assumed.

One on the South Atlantic lying Inaccessible Iceland study, from the year 2018/2019 came to the conclusion that 90% of washed up there empty plastic bottles which 34% constituted of there encountered and investigated garbage, not older than two years old. Since three quarters of the plastic bottles examined were also produced in Asia, the study came to the conclusion that the bottles came from merchant ships and had to be thrown overboard because they could not have traveled the route from Asia in the short time since production. According to the report, this thesis is also supported by the fact that garbage from Asia mainly drifts into the North Pacific and the bottles do not come from African coasts, since China, for example, hardly supplies any water to South Africa. The reason is supported by the increase in trade , which quadrupled from 1992 to 2012. In 2016, 2,400 cargo ships passed through the Tristan da Cunha archipelago , to which Inaccessible Island belongs.

Mediterranean Sea

In the Mediterranean, it is estimated that there is one part of microplastic for every two plankton creatures, or up to 300,000 particles per square kilometer were found (before 2014). In 2018 there were already 1.25 million fragments per square kilometer. In the marine sediments of the Tyrrhenian Sea , up to 182 fibers and 9 fragments per 50 grams of dried sediment were detected, which corresponds to 1.9 million pieces per square meter.

North and east Sea

Approx. 20,000 tons of waste, mainly from shipping and fishing, end up in the North Sea every year . Along examined stretches of beach on the Wadden Sea coast of Germany and Holland , plastic and styrofoam made up over 75 percent of the litter washed up; In 2013, around 600,000 cubic meters of plastic waste were said to have been lying on the bottom of the North Sea. Plastic waste in the North Sea has not decreased in recent years. 90% of the garbage consists of plastics. At 60% of the examined fulmars more than 0.1 grams of plastics could be detected in the stomach.

On the coast of the Baltic Sea there are up to seven pieces of garbage per meter on some stretches of beach, on the coastlines of the Northeast Atlantic ( OSPAR region) an average of 712 pieces of garbage per 100 m of coastline were found in the years 2000 to 2006. Around the UK , an average of 12,000 to a maximum of 150,000 microplastic particles per square kilometer were found.

Pacific

The area of the North Pacific vortex between North America and Asia , also known as the Great Pacific Garbage Patch , is particularly known for its increased concentration of plastic parts . Studies have shown that there are around 1.8 trillion plastic particles in an area of 1.6 million km². Even at the deepest point of the ocean , the Mariana Trench , microplastics have already been found in considerable quantities.

In English-language media, the plastic waste-affected area has been described as twice the size of Texas or twice the size of the United States . A scientist from Oregon State University comes to the conclusion that the highest values published to date would add up to a closed area that would be only one percent the size of Texas. German media compare it with the size of Central and Western Europe . In fact, the size can hardly be specified because the boundaries are diffuse - only the particle concentration can be quantified.

For the Great Pacific Ocean Garbage Patch , one million pieces of plastic per km² are assumed, i.e. one part per square meter. The North Pacific Vortex covers an area of around 1.6 million km². Between 79,000 and 129,000 tons of plastic waste was collected in it. According to information from NOAA, the plastic parts can be found in the top for up to 16 years. Charles Curtis Ebbesmeyer , among others, came up with various current models for landing in the coastal area.

More rubbish swirls

The subtropical eddy of the North Pacific is the largest of the five major current circles in the oceans. But the waste problem has already reached other areas: In the Sargasso Sea in the North Atlantic , high concentrations of plastic waste have also been detected.

There is also a large amount of plastic waste in the northern Atlantic between 22 and 38 degrees north. The maximum density of the plastic particles is one particle per five square meters. This amount is comparable to that contained in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch .

In October 2015, scientists from the Alfred Wegener Institute warned of the possibility of another (the sixth worldwide) garbage vortex in the Barents Sea , the particles of which could be carried as far as the Fram Strait . The parts came from the northern European coasts.

origin

Geographically

According to a study published in Science in early 2015 , the main sources of annual waste are China , Indonesia , Vietnam and the Philippines . In the countries with the 192 coastal regions examined, 275 million tons of plastic waste were produced in 2010, 99.5 million tons of which came from the population who live within a 50-kilometer strip of the respective coast and where probably most of it comes from There were plastic residues, 31.9 million of which were improperly disposed of, which ultimately led to the calculated result. "The 20 countries with the highest pollution rates are responsible for 83% of all improperly treated plastic waste."

It is estimated that around half of the total amount of plastic that enters the world's oceans each year comes from rivers. Calculations by German hydrologists published in mid-October 2017 show that around 90% of this comes from ten rivers, eight in Asia and two in Africa . The longest river in Asia, the Yangtze River (China), and the second largest by the Indus ( Pakistan ) carry the largest amount of plastic waste . In third place is the Yellow River (also China). The other rivers are Hai He (China), Nile (Africa), Ganges (India / Bangladesh), Pearl River (China), Amur (China / Russia), Niger (Africa) and Mekong (Southeast Asia).

According to a study published in 2017 by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN), most of the microplastic inputs come from China, India and South Asia, as well as Africa with the Middle East . Around 16% came from Europe and Central Asia.

Legend: "India" = India / South Asia, "Africa" = Africa / Middle East, "East Asia" = East Asia / Oceania , " South America " = South America , "Europe" = Europe / Central Asia , "North America" = North America.

In Germany , microplastic emissions are around 330,000 tons per year. This corresponds to around 4 kilograms per person.

| Microplastic emissions in Germany (in grams per person) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| origin | Gram | |||

| tires | 1228.5 | |||

| Waste disposal | 302.8 | |||

| asphalt | 228 | |||

| Plastic granulate | 182 | |||

| Sports and playgrounds | 131.8 | |||

| construction sites | 117 | |||

| shoe soles | 109 | |||

| Plastic packaging | 99.1 | |||

| Road markings | 91 | |||

| Textile laundry | 76.8 | |||

| Source: Fraunhofer identifies sources of microplastics | ||||

Fishing nets

Disused, discarded or lost plastic fishing nets , so-called “ ghost nets ”, make up a significant proportion of plastic waste in the oceans and have an impact on the maritime environment, according to the latest studies between 30 and 50%. According to a study by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations FAO from 2016, around 1,250 kilometers of fishing nets per year end up in the European seas as ghost nets; worldwide, fishing is the cause of more than a million tons of plastic waste in the oceans. A fishing nylon net takes up to 600 years to decompose. Around 25,000 of them find their way into the seas uncontrolled every year.

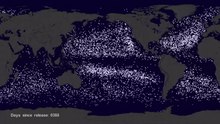

Loss of charge

Losses at sea in container transport are likely to make up the smallest part. The case of the freighter Hansa Carrier , who lost over 60,000 sneakers on May 27, 1990, became known. On the same route as the Hansa Carrier , the cargo ship Ever Laurel lost 29,000 brightly colored toy animals (including yellow plastic ducks), which became known as friendly floatees , on the way from Hong Kong to Tacoma, Washington . Since then, parts of this lost cargo have washed up in Alaska about every three years . Accordingly, the garbage moves at eleven centimeters per second (corresponds to 0.4 km / h ) in a huge circle.

Plastic waste

Plastic waste is washed into the sea via the rivers. In many cases, landfill sites and wild rubbish dumps are also being dumped in the wasteland on rivers, swamps or sea coasts. According to the Federal Environment Agency, plastic bottles need 450 years to decompose.

Tsunami after the Tōhoku earthquake in 2011

Another major source of litter in the North Pacific was the tsunami following the Tōhoku earthquake in 2011 , which washed large quantities of objects of all kinds into the sea that have been floating around since then. The size of the resulting “garbage carpet” is given as an area larger than that of the Federal Republic of Germany .

Tire wear

The abrasion of car tires can be a significant source of micro-plastic entry in the oceans. In Norway, according to estimates by the local environmental authority from 2014, more than half of the total Norwegian microplastic input came from it. Tire wear increases with the total permissible weight of the vehicles and with the engine power (depending on the data source :) 53-200 mg / km mileage for cars, 105-1,700 mg / km for trucks , 1,000-1,500 mg / km for articulated trucks . A similar fine abrasion is the abrasion of the soles of plastic shoes.

artificial grass

According to surveys by the Norwegian environmental authorities arrive annually about 3,000 tons of rubber granules of artificial turf in the local fjords , so would the football field a protective cover for the car tire wear is the second largest emitter of micro-plastic plastic waste in the oceans. There are around three times more artificial turf pitches in Germany than in Norway.

Components

Marine plastic waste consists of used plastic bags , water bottles, disposable razors, CD cases, buckets, cable drums, toothbrushes, lighters and other objects: the tides and the effects of the waves sometimes break the plastics into smaller and smaller pieces.

In the habitat of the lugworms on the North Sea , for example, the plastic polyvinyl chloride makes up more than a quarter of the microplastic particles; This is among other things for window frames, pipes, floor coverings, cable sheathing, different film types and credit cards used.

Some plastics become brittle and break apart as a result of exposure to light and the release of the plasticizers they contain; This is how, among other things, so-called pellets three to five millimeters in size are created , which marine animals mistake for plankton and ingest them. Even smaller fragments and released chemicals are also absorbed and colonized by plankton organisms themselves.

Effect and whereabouts

Plastic waste has a significant impact on marine ecosystems: Larger animals in particular are at risk from mechanical injuries. Seals get stuck in beverage crates or fish and dolphins in abandoned or lost fishing nets , so-called ghost nets .

"It is known of 136 marine species that they regularly get entangled and strangled in garbage"

Sinking

94% of the plastic that ends up in the ocean ends up on the ocean floor . There is now an estimated 70 kg of plastic on every square kilometer of the ocean floor. There it can only decompose with difficulty due to a lack of oxygen and light. The thermohaline circulation creates extensive accumulations of sediment. The highest reported value is 1.9 million particles per square meter.

Some types of algae bind microplastic particles to themselves and could transport them from the sea surface into deeper water layers of the oceans and thus into the local biosphere and food cycle.

Biological effect

Moreover provoke floating as well as superimposed on the seabed plastic parts, the approach of sessile animals or those larvae, for example barnacles , barnacles , hydroids and plants such as ( algae or algae ) (see The Reef Ball Foundation ); in this way they can become starting points for artificial biotopes. In this way, the ocean currents can introduce organisms into foreign ecosystems and possibly displace native species there.

Adsorption of chemicals

Plastic fragments can accumulate toxins (on their surface). Due to their high specific surface , this is particularly true of microplastic particles. If plastic breaks down into microplastics (<5 mm by definition), it can multiply pollutants from the water, for example from oil residues. It then acts like a passive collector, so to speak. A study showed that microplastics contain three to four times as much toxins as the sea floor in its immediate vicinity. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons are preferentially deposited on microparticles made of polyethylene , the most widely used industrial plastic ; it binds about twice as many pollutants as silicone . Some types of plastic adsorb floating crude oil from natural and human sources, giving them a tarry surface.

According to a report from 2009, when polystyrene breaks down, toxins are released.

Confusion with food

Albatrosses and fulmars confuse the pieces of waste with food and eat them. You feel full but eventually starve to death with a garbage-filled stomach. About 1 million seabirds and 100,000 other marine life die this way every year . Charles Curtis Ebbesmeyer found around 100 pieces of plastic in a dead albatross cub that the parent animals had fed it ( National Geographic 10/2005). Whales and dolphins also eat the waste. In March 2019, the largest documented amount of plastic in the stomach of a whale was found when it was discovered during the necropsy of a Cuvier's beaked whale that it had died of 40 kg of plastic waste in its stomach.

Countermeasures

Collect

Various projects (for example the garbage collection ship Manatee ) and researchers are dedicated to collecting the small pieces of plastic in the oceans.

Fishing for litter

The project Fishing for Litter of KIMO aims the North and Baltic Sea clean of plastic waste; Hundreds of thousands of volunteers around the world meet on International Coastal Cleanup Day on September 25th to clean up coasts, bodies of water and river banks. In 2010, the Naturschutzbund Deutschland (NABU) participated in Germany for the first time as part of its Sea without Plastic project . Under the motto Beach Cleanup , Sea Shepherd supports garbage collection campaigns not only limited to marine areas, but also inland on river and lake banks, in cooperation with divers also directly in water. The WWF started a project in March 2016 in which old fishing nets (so-called ghost nets ) are deliberately removed from the Baltic Sea. Continues to make Plogging a contribution to pollution control.

Other initiatives to collect plastic from beaches also achieved international fame, for example the campaign by Afroz Shah and a thousand volunteers in Mumbai or the Final Straw campaign by Pat Smith in Cornwall .

Incentives for fishermen

The German Green-Ocean e. V. started a pilot project in the port of Livorno in 2006 : plastic waste that was fished up was bought from fishermen . This should show that it is entirely possible to remove plastic waste from the ocean cheaply and effectively. In other projects, fishermen are motivated to collect plastic waste and dispose of it in ports. Fishermen in particular should have an interest in keeping their products healthy.

The Ocean Cleanup

The Ocean Cleanup project was presented in October 2012 by the 19-year-old Dutch student Boyan Slat at the TEDx Delft event at the TU Delft as a way to collect and recycle millions of tons of plastic waste from the oceans. The technology is in the testing phase and is based on the use of several manta ray-shaped platforms connected to tubular pontoons floating on the sea surface . The technology makes use of the natural ocean currents and the fact that some of the plastic to be collected is floating on the ocean surface. This has the advantage that plankton and other sea creatures are not caught. He estimates that it will take about five years to clean each large oceanic eddy. On June 22, 2016, a 100 meter long prototype went into operation off the Dutch North Sea coast. On September 8, 2018, the first functional system, called "System 001", was sent on its way to the "Great Pacific garbage patch". At the beginning of January 2019, damage to this system became known, which made repairs on land necessary. So far, only 2,200 kilograms of plastic could be collected. The second attempt started on June 21, 2019.

Pacific Garbage Screening - PGS

The association Pacific Garbage Screening was founded in November 2016 by a team led by Marcella Hansch in Aachen based on her thesis at RWTH Aachen University . The aim of the association is to develop a technology that can remove not only coarse plastic waste, but also small plastic particles from the sea.

PGS is based on the idea of a floating platform. The special design is intended to calm waves and currents within the platform in such a way that the plastic particles in the sea rise and collect in the high points of the platform, where they are removed from the water. Due to this passive sedimentation principle ("reverse sedimentation"), the approach works without nets and marine life is not endangered.

Marcella Hansch and her team have so far been working on a voluntary basis on a feasibility study and the implementation of the technology. With the association founded, they also want to draw attention to the pollution of the seas. For their commitment and the idea of Pacific Garbage Screening , Hansch won the award 25 women, whose inventions change our lives 2017 and the federal award EcoDesign in the young talent category.

Preventive measures

Household garbage

Banning the disposal of household waste via rivers into the sea is another major concern.

Free disposal

It must be possible to unload the garbage free of charge in all ports and the garbage must be disposed of properly on land.

Prohibition of entry via ships

The introduction of plastic waste into the oceans by ships was banned as early as 1988 with the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL) in Annex V : The ship's command of commercial ships is obliged to keep a log of all waste accumulating on board in a so-called garbage diary to lead. The delivery on land must be proven by means of a receipt . Violations of these provisions can result in severe fines ; In Germany, fines of up to € 50,000 can be imposed in accordance with the ordinance on violations of the 1973 international convention for the prevention of marine pollution from ships and the 1978 protocol to this convention (MARPOL infringement ordinance) .

Composition of plastics

The aim is also to use more readily biodegradable plastics and more environmentally friendly polymers , additives and fillers . Scientists at the University of Southern Mississippi have optimized some polymers for disintegration in seawater. Degradation-promoting additives, however, have proven to be ineffective. A study published in April 2019 shows that these novel materials are not sufficiently biodegradable and can accumulate in the environment.

Disposable Plastic Policy

In May 2019, the EU passed the Single-Use Plastic Directive - Directive (EU) 2019/904 on reducing the impact of certain plastic products on the environment. For certain single-use products made of plastic, such as single-use dishes , drinking straws and cotton swabs with plastic content, a trade ban will apply from 2021.

reception

- Addicted to plastic (film)

- A Plastic Ocean (film)

- The plastic beach of Hawaii - Where the world's garbage goes ashore (radio report)

- End of the line sea? The plastic waste project (exhibition, project)

- Plastic Planet (book, film)

- Trashed (documentation)

- Vincent Perazio: Microplastics in the Sea: Invisible, but also Safe? , ARTE France & Via Découvertes, arte 2016

See also

literature

- Boris Worm, Heike K. Lotze, Isabelle Jubinville, Chris Wilcox and Jenna Jambeck: Plastic as a Persistent Marine Pollutant . In: Annual Review of Environment and Resources . tape 42 , October 2017, doi : 10.1146 / annurev-environ-102016-060700 (Open Access).

- Callum Roberts: Man and the Sea: Why the largest living space on earth is in danger (original title: Ocean of Life , translated by Sebastian Vogel) DVA, Stuttgart 2013, p. 218f, ISBN 978-3-421-04496-9 .

- Charles Moore (with Cassandra Phillips): Plastic Ocean: How a Sea Captain's Chance Discovery Launched a Determined Quest to Save the Oceans , Avery, New York 2011, ISBN 978-1-58333-501-7 .

- Melanie Bergmann, Lars Gutow, Michael Klages: Marine Anthropogenic Litter , 2015, 456 S., doi: 10.1007 / 978-3-319-16510-3 .

Broadcast reports

- Anja Krieger and Christine Westerhaus : Particle catcher - ideas against microplastics in the sea , Deutschlandfunk - “ Science in focus ” from June 4, 2017

Web links

- Alfred Wegener Institute , litterbase.awi.de: Online Portal for Marine Litter (" Online Portal for Maritime Garbage")

- seilnacht.com: The pollution of the seas

- Helmholtz Association of German Research Centers , Earth System Knowledge Platform / Knowledge Platform Earth and Environment , themenspezial.eskp.de: Plastic in Waters

- visualcapitalist.com, April 21, 2018, Nick Routley: Visualizing the Prolific Plastic Problem in Our Oceans (English; "Visualizing the growing plastic problem in our oceans")

- 3 July 2019, Iman Ghosh: Mapping the Flow of the World's Plastic Waste ("Map of the global plastic waste path")

Organizations

- Congress documents of the GESAMP workshop on microplastic small parts, 28. – 30. June 2010, Paris: Proceedings of the GESAMP International Workshop on micro-plastic particles as a vector in transporting persistent, bio-accumulating and toxic substances in the oceans , jodc.go (2.19 MB)

- Plastic waste in the sea , nabu.de (February 25, 2015)

- An oceanographer against plastic waste ( memento from February 10, 2013 in the web archive archive.today ), 3sat.de, nano

- Facts and figures on marine pollution , UNESCO

- WWF plastic report: The big plastic bankruptcy. In: wwf.de . Retrieved on March 5, 2019 : "New WWF report on plastic waste: Global UN convention against the plastic flood is overdue"

newspapers and magazines

- Güven Purtul: Plastic in the stomach . In: Süddeutsche Zeitung , May 17, 2010

- 46,000 plastic parts on one square kilometer . In: Die Welt , June 9, 2009

- Kara Lavender Law, Skye E. Morét-Ferguson, Deborah S. Goodwin, Erik R. Zettler, Emelia DeForce, Tobias Kukulka, Giora Proskurowski: Distribution of Surface Plastic Debris in the Eastern Pacific Ocean from an 11-Year Data Set . Environmental Science & Technology 2014, 48 (9), 4732-4738; doi: 10.1021 / es4053076

- Marcus Eriksen, Laurent CM Lebreton, Henry S. Carson, Martin Thiel, Charles J. Moore, Jose C. Borerro, Francois Galgani, Peter G. Ryan, Julia Reisser: Plastic Pollution in the World's Oceans: More than 5 Trillion Plastic Pieces Weighing over 250,000 tons of Afloat at Sea. PLoS ONE 2014, 9 (12), doi: 10.1371 / journal.pone.0111913

- bigthink.com, August 10, 2018, Frank Jacobs: Just 10 streams carry 95% of all river-borne plastic into the ocean ("Only ten rivers bring 95% of all corresponding plastics into the oceans")

Individual evidence

- ^ Resonator podcast of the Helmholtz Association : Garbage in the Sea (episode 51, January 16, 2015)

- ↑ a b J. R. Jambeck, R. Geyer, C. Wilcox, TR Siegler, M. Perryman, A. Andrady, R. Narayan, KL Law: Plastic waste inputs from land into the ocean. In: Science. 347, 2015, pp. 768–771, doi: 10.1126 / science.1260352

- ↑ a b c Badische Zeitung , February 14, 2015, badische-zeitung.de: More garbage in the sea .

- ↑ a b Helmholtz Association of German Research Centers , eskp.de: Earth System Knowledge Platform (ESKP), knowledge platform “Earth and Environment”, research topic: Garbage in the sea (July 12, 2016).

- ↑ Peter Haffner : An inkling of the apocalypse. In: NZZ Folio . 07/09.

- ^ Daniel Lingenhöhl: Spektrum.de: A new rock called plastiglomerate . Spectrum of Science , June 13, 2014. From: Angus Chen: sciencemag.org: Rocks Made of Plastic Found on Hawaiian Beach , June 4, 2014 (June 15, 2014).

- ↑ Daniel Lingenhöhl: Environmental pollution: plastic rust is spreading. In: Spektrum.de . November 15, 2019, accessed November 18, 2019 .

- ↑ a b Samiha Shafy: Environment: The Garbage Carousel . In: Spiegel Online , February 2, 2008.

- ↑ a b Virgin plastic granules on some beaches of Eastern Canada and Bermuda, Murray R. Gregory, February 13, 1983, Marine Environmental Research , Volume 10, Issue 2, 1983, pp 73-92, doi: 10.1016 / 0141-1136 (83) 90011-9

- ↑ SECURVITAL - Das Magazin , 4/012, p. 5: Textiles - Fleece in the Sea , November 24, 2012.

- ↑ a b Kathy Marks, Daniel Howden: The world's rubbish dump: a tip that stretches from Hawaii to Japan. In: The Independent . February 5, 2008, accessed January 13, 2015 .

- ↑ How can we create a world where plastic never becomes waste? Summary of the study at the WEForum, January 19, 2016; the complete study: http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_The_New_Plastics_Economy.pdf

- ↑ More plastic than fish in the sea in 35 years , Die Zeit, January 19, 2016.

- ↑ Garbage Patch Visualization Experiment (April 21, 2017)

- ^ NOAA: Info: Patch , Marine Debris Program , accessed February 27, 2012.

- ↑ Plastic rubbish blights Atlantic Ocean , BBC News, February 24, 2010.

- ↑ a b deutschlandfunk.de , Research Current , April 21, 2017, Lucian Haas: Barents Sea - a dead end for plastic waste in the sea (April 21, 2017)

- ↑ Marine Litter - An analytical overview (PDF; 9.0 MB) United Nations Environment Program , 2005

- ^ NOAA Marine Debris Program - FAQs , accessed February 27, 2012.

- ↑ Die Denker , July 2, 2014, 88% of the ocean's surfaces are polluted by plastic particles .

- ↑ a b Environment and Consumers , Deutschlandfunk , April 11, 2013, Anja Nehls: Müllhalde Meer , deutschlandfunk.de, December 12, 2013.

- ^ Wissenschaft im Brennpunkt , Deutschlandfunk , April 7, 2013; Anja Krieger: The waste disposal of the seas , deutschlandfunk.de, December 12, 2013.

- ↑ More and more plastic waste in the Arctic deep sea , Scinexx from: Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research , October 22, 2012.

- ↑ Question 3 - AWI. Retrieved May 17, 2018 .

- ↑ Garbage dump Ocean , Badische Zeitung , Education & Knowledge December 13, 2014

- ↑ Marcus Eriksen, Laurent CM Lebreton, Henry S. Carson, Martin Thiel, Charles J. Moore, Jose C. Borerro, Francois Galgani, Peter G. Ryan, Julia Reisser: Plastic Pollution in the World's Oceans: More than 5 Trillion Plastic Pieces Weighing over 250,000 tons of Afloat at Sea. PLoS ONE 2014, 9 (12), doi: 10.1371 / journal.pone.0111913 .

- ^ Die Welt , December 18, 2014, Anja Garms, Where ridiculous amounts of plastic waste disappear. .

- ↑ Pollution - How plastic waste ends up in the ocean . In: Deutschlandfunk . ( deutschlandfunk.de [accessed on October 13, 2017]).

- ↑ Ilka Peeken, Sebastian Primpke, Birte Beyer, Julia Gütermann, Christian Katlein, Thomas Krumpen, Melanie Bergmann, Laura Hehemann & Gunnar Gerdts: Arctic sea ice is an important temporal sink and means of transport for microplastic . In: Nature Communications . 2018, doi : 10.1038 / s41467-018-03825-5 .

- ^ The long-term legacy of plastic mass production . In: Science of The Total Environment . tape 746 , July 22, 2020, ISSN 0048-9697 , p. 141115 , doi : 10.1016 / j.scitotenv.2020.141115 ( sciencedirect.com [accessed August 24, 2020]).

- ↑ DER SPIEGEL: Floating garbage chutes: Study diminishes hope for plastic-free seas - DER SPIEGEL - Wissenschaft. Retrieved August 24, 2020 .

- ↑ badische-zeitung.de , May 27, 2017, Roland Knauer: Before Greenland, plastic waste sinks into the depths (June 11, 2017).

- ↑ Badische-zeitung.de , October 24, 2015: Plastic waste in the Arctic .

- ↑ Ilka Peeken et al. a .: Arctic sea ice is an important temporal sink and means of transport for microplastic . In: Nature Communications . tape 9 , no. 1505 , 2018, doi : 10.1038 / s41467-018-03825-5 .

- ↑ deutschlandfunk.de , research news, reports , February 22, 2016: Microplastics in front of New York (February 26, 2016); peconicbaykeeper.org .

- ↑ Katsiaryna Pabortsava, Richard S. Lampitt: High Concentrations of plastic hidden beneath the surface of the Atlantic Ocean . In: Nature Communications . tape 11 , no. 1 , August 18, 2020, ISSN 2041-1723 , p. 1–11 , doi : 10.1038 / s41467-020-17932-9 ( nature.com [accessed August 19, 2020]).

- ^ Fiona Harvey: Atlantic ocean plastic more than 10 times previous estimates. In: The Guardian. August 18, 2020, accessed August 19, 2020 .

- ↑ Plastic waste: How sailors pollute the sea. In: Spiegel Online. September 30, 2019, accessed September 30, 2019 .

- ↑ Peter G. Ryan, Ben J. Dilley, Robert A. Ronconi, Maëlle Connan: Rapid increase in Asian bottles in the South Atlantic Ocean indicates major debris inputs from ships . In: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences . September 25, 2019, ISSN 0027-8424 , p. 201909816 , doi : 10.1073 / pnas.1909816116 ( pnas.org [accessed September 30, 2019]).

- ↑ a b c Jochen Steiner: Microplastics threaten living beings in the sea. In: Deutschlandfunk . July 2, 2014, accessed August 24, 2020 .

- ↑ WWF Switzerland : WWF Report: Record amounts of microplastics in the Mediterranean In: wwf.ch, June 8, 2018, accessed on June 23, 2018.

- ^ Ian A. Kane, Michael A. Clare, Elda Miramontes, Roy Wogelius, James J. Rothwell, Pierre Garreau, Florian Pohl: Seafloor microplastic hotspots controlled by deep-sea circulation. In: Science. April 30, 2020, p. Eaba5899, doi : 10.1126 / science.aba5899 .

- ↑ a b Plastic in the North and Baltic Seas , Naturschutzbund Deutschland , December 14, 2013.

- ^ A b Annett Stein: Plastic waste poisoned key species of the North Sea , Die Welt , December 7, 2013, accessed on December 12, 2012.

- ↑ Bayerischer Rundfunk quotes the Federal Environment Agency

- ↑ Status report on the North Sea shows need for action Olaf Lies: The federal government should campaign internationally for tracking devices on dangerous goods containers. In: Environment.niedersachsen.de . January 8, 2019, accessed January 14, 2019 .

- ↑ NOAA 'S RESPONSE AND RESTORATION BLOG , June 22, 2012, Ashley Braun: How Big Is the “Great Pacific Garbage Patch”? Science vs. Myth ( April 26, 2017 memento in the Internet Archive ) (April 21, 2017), How Big Is the "Great Pacific Garbage Patch"? Science vs. Myth, updated February 7, 2013 .

- ↑ Pacific: Garbage vortex is more than four times the size of Germany . In: Spiegel Online . March 22, 2018 ( spiegel.de [accessed March 23, 2018]).

- ↑ L. Lebreton, B. Slat, F. Ferrari, B. Sainte-Rose, J. Aitken, R. Marthouse, S. Hajbane, S. Cunsolo, A. Schwarz, A. Levivier, K. Noble, P. Debeljak , H. Maral, R. Schoeneich-Argent, R. Brambini, J. Reisser: Evidence that the Great Pacific Garbage Patch is rapidly accumulating plastic . In: Scientific Reports . tape 8 , no. 1 , December 2018, doi : 10.1038 / s41598-018-22939-w .

- ^ The Great Pacific Garbage Patch. The Ocean Cleanup, accessed October 25, 2019 .

- ↑ X. Peng, M. Chen, S. Chen, S. Dasgupta, H. Xu, K. Ta, M. Du, J. Li, Z. Guo, S. Bai: Microplastics contaminate the deepest part of the world's ocean . In: Geochemical Perspectives Letters . 2018, ISSN 2410-3403 , pp. 1-5. doi : 10.7185 / geochemlet . 1829 .

- ^ Worse Than Climate Change. (No longer available online.) In: WGBH . November 8, 2011, archived from the original on January 13, 2012 ; accessed on January 13, 2015 (video, Capt. Charles Moore on his new book, Plastic Ocean; 7:24 min).

- ↑ Brian Craft: Giant Ocean-Trash Vortex Attracts Explorers. In: National Geographic News . July 31, 2009, accessed January 13, 2015 .

- ↑ Exaggerated the size of the Pacific garbage vortex? , scinexx , January 6, 2011.

- ↑ faz.net , January 24, 2011, Rüdiger Schacht: The old sea and the garbage

- ↑ Pia Heinemann : Huge field of plastic waste discovered in the Atlantic. In: Welt online . February 25, 2010.

- ^ Spiegel.de , February 2, 2008, Samiha Shafy: Das Müll-Karussell .

- ↑ http://response.restoration.noaa.gov/about/media/how-big-great-pacific-garbage-patch-science-vs-myth.html .

- ↑ Florian Rötzer: Gigantic plastic waste dump in the sea , in: Telepolis from August 28, 2009.

- ↑ L. Lives Reton et al .: Evidence did the Great Pacific Garbage Patch is Rapidly accumulating plastic. March 22, 2018, accessed November 10, 2019 .

- ↑ Vortex in the Pacific: Plastic waste drives carousel , Spiegel Online, January 15, 2007.

- ↑ Victoria Gill: Plastic rubbish blights Atlantic Ocean. In: BBC News . February 24, 2010, accessed August 24, 2020 .

- ↑ Plastic garbage in the Arctic: researchers fear a new giant garbage vortex. In: feelgreen.de. October 22, 2015, archived from the original on January 5, 2016 ; accessed on August 24, 2020 .

- ↑ Christoph Behrens: The Yangtze washes the most plastic into the sea . In: Süddeutsche Zeitung . October 13, 2017 ( sueddeutsche.de ).

- ^ Christian Schmidt, Tobias Krauth, Stephan Wagner: Export of Plastic Debris by Rivers into the Sea . In: Environmental Science & Technology . 51, No. 21, October 11, 2017, pp. 12246–12253. bibcode : 2017EnST ... 5112246S . doi : 10.1021 / acs.est.7b02368 . PMID 29019247 . "The 10 top-ranked rivers transport 88–95% of the global load into the sea"

- ↑ Julien Boucher, Damien Friot: Primary Micro Plastics in the Oceans . Ed .: IUCN. 2017, ISBN 978-2-8317-1827-9 , doi : 10.2305 / IUCN.CH.2017.01.en ( iucn.org [PDF; accessed August 21, 2017]). ; Page 28

- ↑ Fraunhofer identifies sources of microplastics , 2018

- ↑ Ghost nets - deadly danger on www.wwf.de , August 17, 2018

- ↑ Michael Weiland: Undead under water. Greenpeace , May 13, 2016, accessed July 14, 2016 .

- ↑ Cosmetics do not solve the problem , Taz , July 3, 2014, accessed on July 7, 2014.

- ↑ Federal Environment Agency: How long does the garbage in the sea need to be broken down? ( Memento of March 11, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) , 2013.

- ↑ Donovan Hohn: Moby-Duck: The True Story of 28,800 Bath Toys Lost at Sea & of the Beachcombers, Oceanograp hers, Environmentalists & Fools Including the Author Who Went in Search of Them . Penguin, 2011, ISBN 978-1-101-47596-6 ( google.de [accessed on March 26, 2018]).

- ↑ Dietmar Bartz: Unterwegs - Bade-Entchens last Ufer , NZZ Folio 04/02, accessed on August 6, 2010.

- ↑ Gigantic vortex transports plastic waste through the Atlantic , Access to sustainable knowledge, January 15, 2007, accessed on August 6, 2010.

- ↑ ASK Access to sustainable Knowledge , accessed on July 28, 2013.

- ↑ Indonesia: Citarum - the poison flow , ARD-Weltspiegel, at daserste.de

- ^ Christian Schmidt, Tobias Krauth and Stephan Wagner: Export of Plastic Debris by Rivers into the Sea . In: Environmental Science and Technology . 2017, doi : 10.1021 / acs.est.7b02368 .

- ↑ Constantin Vogt, Carmen Schnaidt: Life from Garbage, Garbage Collectors in Cebu City , PDF file available online

- ↑ Eva Krafczyk, dpa: Garbage dump poisons slum , n-tv.de.

- ↑ Federal Environment Agency: How long does the garbage in the sea need to be broken down? ( Memento of March 11, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) , 2013.

- ↑ Tsunami junk from Japan floating in the Pacific ( Memento from November 2, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) , tagesschau.de , November 1, 2011, accessed on April 7, 2012.

- ^ Peter Sundt, Per-Erik Schulze, Frode Syversen: Sources of microplastics-pollution to the marine environment. , 2014; Pages 39-41 and Tables 8-1 and 8-2 (p. 88).

- ↑ Gebbe, Hartung, Berthold: Quantification of tire wear from motor vehicles in Berlin. Part II: Final Report. ; P. 77; Technical University of Berlin, Institute for Road and Rail Transport, ISS Vehicle Technology; 1997, quoted by Birgit Kocher: Substance entries in the street side area - tire wear ; Page 7; Reports of the Federal Road Research Laboratory; Traffic engineering booklet V; 188; Wirtschaftsverlag NW Verlag für neue Wissenschaft GmbH, Bremerhaven; 2010; ISBN 978-3-86509-976-1 ; ( PDF file )

- ↑ . Hillenbrand Th, Touissant D., E. Böhm, Fuch S., Scherer U., Rudolphi A., Hoffmann M., J. Kreißig, Kotz Ch .: (2005) entries of copper, zinc and lead in water and soils - analysis of emissions ; quoted by Birgit Kocher: substance entries in the street side area - tire wear ; Page 8; Reports of the Federal Road Research Laboratory; Traffic engineering booklet V; 188; Wirtschaftsverlag NW Verlag für neue Wissenschaft GmbH, Bremerhaven; 2010; ISBN 978-3-86509-976-1 ; ( PDF file )

- ↑ https://www.br.de/themen/wissen/inhalt/mehr-mikroplastik-durch-reifenabrieb-als-durch-kosmetik-100.html

- ↑ Artificial turf is the second largest source of microplastics in the sea . In: Deutschlandfunk Nova . ( deutschlandfunknova.de [accessed June 30, 2018]).

- ↑ Plastic Planet - The dark side of plastics , layout for the book , orange-press.com (PDF; 4.1 MB).

- ^ Daniela Weingärtner, dpa: Brussels declares war on plastic waste , Badische Zeitung , November 5, 2013, accessed on December 12, 2013.

- ↑ Chris Sherrington: Plastics in the Marine Environment . In: Eunomia. June 1, 2016, accessed May 16, 2020.

- ↑ Melanie Bergmann, Lars Gutow, Michael Klages: Marine Anthropogenic Litter , 2015, doi: 10.1007 / 978-3-319-16510-3

- ^ Ian A. Kane, Michael A. Clare, Elda Miramontes, Roy Wogelius, James J. Rothwell, Pierre Garreau, Florian Pohl: Seafloor microplastic hotspots controlled by deep-sea circulation. In: Science. April 30, 2020, p. Eaba5899, doi : 10.1126 / science.aba5899 .

- ^ To ( memento of October 23, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Richard Thompson .

- ↑ Helmholtz Knowledge Platform "Earth and Environment", ESKP: Pollutant Magnet Microplastics. In: ESKP special topic "Plastic in Waters". November 7, 2017, accessed February 20, 2018 .

- ↑ Informationsdienst Wissenschaft , August 1, 2016, Katharina Jeorgakopulos, idw-online.de: Alarming results: pollution from microplastics in the sediment higher than expected

- ↑ sueddeutsche.de , August 1, 2016 Kathrin Zinkant: Microplastics: Like a magnet for pollutants

- ↑ Katsuhiko Saido et al., Algalita.org, Marine Research and Education : New contamination derived from marine debris plastics , 238th ACS National Meeting

- ↑ Plastic waste in the sea - facts and figures. (PDF; 289 kB) In: Wissenschaftsjahr.de. Retrieved January 14, 2019 .

- ↑ Plastic waste poisons the world's oceans , Society for the Rescue of Dolphins , January 12, 2011

- ↑ http://www.plastic-sea.com/?file=projekt_beschreibung&language=german ( Memento from December 24, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Sperm whale from the Mediterranean Sea dies of plastic waste , March 9, 2013.

- ↑ "Whale that starved to death had record 40kg of plastic waste in its stomach" Independent.co.uk of March 18, 2019

- ↑ a b Christian Rauch: On the long journey to plastic waste . In: brand eins . Volume 15, Issue 7, July 2013, ISSN 1438-9339 , p. 54-58 .

- ↑ Garbage boats collect more rubbish off the coast of Mallorca in June. In: mallorcazeitung.es . July 15, 2019, accessed on July 15, 2019 : “The 30 garbage boats of the Balearic Ministry of the Environment, which have been in use since May 1, fished 14.5 tons of waste out of the water in June, which corresponds to around 484 kilos per day . "

- ↑ Kim Detloff: For a sea without garbage . Deutschlandradio Kultur , April 10, 2013, accessed on December 12, 2013 (interview with Gabi Wuttke).

- ↑ Organize your own beach cleanup! Sea Shepherd Germany e. V., archived from the original on November 24, 2015 ; accessed on November 24, 2015 .

- ↑ Ghost nets in the Baltic Sea - project progress . wwf.de, as of June 23, 2016, accessed on June 11, 2017.

- ↑ Nadja Ayoub: World's largest garbage collection campaign in Mumbai: This is what the beach looks like after almost 3 years. In: utopia.de. September 15, 2018, accessed August 14, 2019 .

- ^ Louise Bevan: 70-Year-Old 'Action Nan' Cleans 52 Beaches and Starts Radical Anti-Plastic Campaign. In: The Epoch Times. March 18, 2019, accessed on August 14, 2019 .

- ↑ About Pat. In: finalstrawcornwall.co.uk. Retrieved on August 14, 2019 .

- ↑ The numbers speak tough language , November 11, 2008, accessed April 30, 2012.

- ↑ Never grow up , TEDxDelft, October 5, 2012 found.

- ↑ How the oceans can clean themselves: Boyan Slat at TEDxDelft , YouTube.

- ^ The Concept: The Ocean Cleanup. Retrieved September 29, 2014 .

- ^ North Sea Prototype. theoceancleanup.com, accessed July 17, 2016 .

- ↑ The floating garbage barrier fishes away plastic. n-tv.de, June 23, 2016, accessed on July 17, 2016 .

- ^ "The Ocean Cleanup": Garbage collection on the sea begins. nzz.ch, September 9, 2018, accessed on September 10, 2018 .

- ↑ Sinan Recber: Breakdown in plastic catcher "Ocean Cleanup": Wilson can no longer . In: The daily newspaper: taz . January 3, 2019, ISSN 0931-9085 ( taz.de [accessed January 3, 2019]).

- ↑ Tina Baier: Nobody saves us from plastic waste. In: sueddeutsche.de . January 4, 2019, accessed January 4, 2019 .

- ↑ Gabriel Knupfer: Plastic in the oceans: High-tech is not a solution either. In: handelszeitung.ch . June 26, 2019, accessed July 9, 2019 .

- ↑ spiegel.de: Marcella Hansch wants to save the sea

- ↑ Home - Pacific Garbage Screening. Retrieved August 16, 2018 .

- ↑ handelsblatt.com: 25 women who are changing our world

- ^ Lutz Reidt: Plastic instead of fish in the stomach , Deutschlandradio Kultur, March 2, 2008.

- ↑ Manfred Lindinger: Plastic dissolves in sea water. FAZ , April 3, 2007, accessed on November 19, 2018 .

- ↑ Wolfgang W. Merkel: New plastic dissolves in sea water. Die Welt , March 28, 2007, accessed November 19, 2018 .

- ↑ Susan Selke, Rafael Auras, Tuan Anh Nguyen, Edgar Castro Aguirre, Rijosh Cheruvathur, Yan Liu: Evaluation of Biodegradation-Promoting Additives for Plastics. In: Environmental Science & Technology. 49, 2015, p. 3769, doi: 10.1021 / es504258u

- ↑ Imogen E. Napper, Richard C. Thompson: Environmental Deterioration of Biodegradable, Oxo-biodegradable, Compostable, and Conventional Plastic Carrier Bags in the Sea, Soil, and Open-Air Over a 3-Year Period. In: Environmental Science & Technology. 2019, doi: 10.1021 / acs.est.8b06984 .

- ↑ https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/DE/TXT/?uri=OJ:L:2019:155:TOC

- ↑ Fight plastic waste. In: bundesregierung.de . May 22, 2019, accessed May 30, 2019 .

- ↑ Anja Krieger: Weltzeit , Deutschlandradio Kultur , July 7, 2011, accessed on July 25, 2013.

- ↑ End of the line sea? The plastic waste project , museum-gestaltung.ch, July 25, 2013.

- ↑ https://www.plasticgarbageproject.org/

- ↑ trashedfilm.com