fulmar

| fulmar | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Fulmar ( Fulmarus glacialis ) |

||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||

|

||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||

| Fulmarus glacialis | ||||||||||

| ( Linnaeus , 1761) |

The fulmar ( Fulmarus glacialis ) or North Atlantic fulmar belongs to the petrel family . As the only seagull petrel north of the equator, it spends most of its time over the open sea. It feeds on krill , fish , snails , crabs , cephalopods , molluscs and jellyfish . He also eats carrion and fish waste. During the breeding season, the fulmar defends itself against predators and nest robbers by spitting on them with its stomach oil. This bird was an important source of food for the Vikings .

description

The fulmar is 45–53 cm tall and weighs 650–1000 g. The wingspan is 101 to 117 cm. At the breeding colonies, the bird makes cackling, chuckling and nasal noises. On the high seas he is less cheerful.

In the adult fulmar the head, neck and underside are dark gray or white. The plumage on the top of the wings is gray-blue. The rump and tail are usually lighter gray, the latter is also rounded. The sexes are colored the same, males are usually slightly larger than females. The legs are short and yellowish green. Unlike many seagulls , the bird does not show black wing tips when in flight.

Taking into account the plumage dimorphism , a distinction is made between two groups: On the one hand, the populations of the gray or dark morph, which in the High Arctic and the Lower Arctic Bear Island have a share of almost 85 to 90 percent. On the other hand, the populations of the white morph that live in the boreal North Atlantic . In addition, populations of at least one percent gray birds can be found in the Lower Arctic West Greenland (including the High Arctic Thule region ) and in the High Arctic Jan Mayen . In addition, there are many more gray and dark individuals than white individuals in places on the Pacific coast near the Arctic .

The fulmar has dark eyes that are emphasized by a gray rein mark. The beak is short and strong. It is predominantly yellow in color, becomes darker towards the tip of the nose and varies between black mottling on and near the nostrils. As with all tubular noses, the nostrils are elongated like a tube. With regard to the beak lengths, three groups are distinguished: Short beaks (less than 37 mm) are found in the whole of the High Arctic, medium-long ones (38 to 39 mm) in the Lower Arctic, on Jan Mayen and Thule, and the long ones (more than 40 mm) in the boreal one North Atlantic.

The fulmar can briefly dive up to four meters deep. After a short run he rises from the water.

flight

The fulmar sails with rigidly spread wings and tilts the body sometimes to one side and sometimes to the other. Most of the time it flies close to the water. It aligns its flight with the rising and falling of the waves. Its wingbeats are quick and short. In the vicinity of cliffs, the updrafts allow him to glide.

distribution and habitat

The fulmar is common in the north of the Atlantic and Pacific and nests on rocky islands and along cliffs. During the breeding season it does not move more than 30 to 40 km away from its colonies. The rest of the year he roams the sea. It winters on the coasts, rarely inland.

There are 16 colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America . Five of them are on Newfoundland and Labrador . Another eleven colonies are spread across Arctic Canada , Baffin Island and Devon Island .

Also on Spitsbergen there are breeding colonies. These are mainly located on the west coast and on Bear Island .

In Europe there are colonies on Iceland, on the northern coast of Ireland , in Scotland and generally in Scandinavia , but also in Denmark , the Netherlands and on Heligoland and in northern France .

Way of life

nutrition

The fulmar feeds on krill , fish , snails , crabs , cephalopods , molluscs and jellyfish . He also eats carrion and fish waste. The food is picked or submerged from the surface of the water.

Fulmars often swallow plastic parts along the shipping routes of the North Sea . Stomach examinations show that these specimens are four times more contaminated than the birds of the Faroe Islands . The plastic waste in the North Sea has not decreased in recent years. 90% of the garbage consists of plastics. In 60% of the fulmars examined, more than 0.1 gram of plastic could be detected in the stomach.

behavior

The fulmar is diurnal and strictly territorial during the breeding season. The dispute over food is resolved by loud cackling. In places with a lot of food it forms swarms. Sometimes several thousand birds gather to feed on the drifting carcass of a whale . Fulmars drifting inattentively on the water can be caught and preyed by sharks as soon as they have learned the correct hunting technique. With the exception of an acute attack, the birds cannot be disturbed when they are resting or when they are looking for food.

Adult fulmars defend their territory against native and alien competitors. They seldom engage in dangerous fights against conspecifics. Most of the time, quarrels at the breeding site are fought out with aggressive threatening gestures, which end with the competitors snapping at the other's wings. If the loser does not withdraw, he will be spat on with stomach oil until he leaves.

The fulmar defends its nest by making coughing noises, falling against the intruder, and poking volleys of yellow stomach oil from its beak. The fulmar aims 50 to 100 cm, sometimes 200 cm. He can spit several times in a row, albeit in decreasing amounts. The oil has an unpleasantly sweet, fishy odor that has a repellent effect. The stomach oil is mostly used to defend against skuas and cats that are poaching , but it is also very effective against birds of prey and other sea birds (especially kittiwakes , puffins ). Due to sticky and damaged feathers, these birds often die. Even young birds can spew stomach oil against anyone who approaches them.

The fulmar can become contaminated with its own stomach oil, but it can be removed by bathing and preening its plumage. Because other birds are unable to dispose of the oil in the same way, there must be a mechanism in place that gives fulmars "immunity" to the effects of the oil. Fisher also reports that fulmars use small amounts of the stomach oil in cleaning their plumage to apply it to their feathers. Warham suspects that fulmars have a special feather structure.

The stomach oil consists mainly of triglycerides and unsaturated fatty acids . The oil has a low viscosity with a specific gravity of 0.88. It condenses into a wax at cool temperatures. The color varies from colorless to deep reddish brown, but is often clear yellow.

In addition to stomach oil, all fulmars have a characteristic musky odor , which penetrates the eggs and is believed to deter egg thieves. In old Icelandic it is called fūlmār because of this behavior or its own smell, which means "stinking gull". Sa: foul maa. [10] [6]

Reproduction and development

The fulmar begins its first brood between the ages of six and twelve. In spring and early summer it usually breeds near other sea birds. The colonies, which are often large, are usually found in rock walls above the surf up to a height of a few hundred meters. At the breeding site, the birds lie on their stomachs and push themselves under the edge of the rock in case of danger.

Courtship and mating

In the period from March to April the fulmars appear in front of the breeding rock, but initially do not go ashore. The males arrive first and courtship on the water, rhythmically lifting their bodies, flapping their wings and screaming. In the case of the populations in the Pacific, they also tear open the beak and show the partner the bright orange throat.

After successful courtship on the water, the male stays near the selected female. Some time later, the female cackles loudly and gently pokes her beak several times. At regular intervals it brings him food to show that he can support a family. After a while, copulation finally occurs . The couples stay together for a lifetime.

Brood care

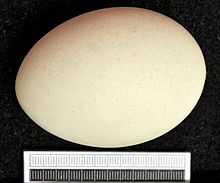

At the end of winter, the fulmars move into their nesting sites, but do not hatch the eggs until May. They nest on bare rock ledges, inaccessible ledges, in small caves on the top floors of the rock face. Some pairs also breed on the ground. The nest is a shallow hollow that is sometimes padded with grass or bordered with small stones. Between May and August, a single white egg is incubated by both parents for 48 to 57 days, which peel off every few days. If the egg is stolen or broken, the female will not lay a new one.

In the middle of June the young bird hatches, wearing a very thick down fur. The head, neck and lower half of the body are white and gray. The rest of the plumage is colored smoke gray. For the first two weeks, one parent warms the young while the other adult bird searches for food. The young bird is fed an oily pulp made from half-digested cephalopods , molluscs and jellyfish , so that it becomes noticeably fat. After two weeks he is left alone all day and only fed once a day. If someone approaches the nest in the absence of their parents, he spits oil on them as a defense. At the age of three weeks he can distinguish his parents from intruders for the first time. The nestling period lasts 41 to 57 days. After six to eight weeks of feeding time - as soon as the young bird moves a few steps out of the nest - the adult birds move back to the high seas and leave them to their own devices. When they are 50 to 60 days old, they fall off the rocks and float on the sea, unable to fly . It absorbs plankton from the surface and feeds on its fat reserves until the plumage has grown completely and it is able to fly.

The young birds leave the colony in July or August. The not yet sexually mature non-breeders spend their time on the high seas in autumn and winter. Between August and October, the adult birds do their moulting in European waters and overwinter there. Individual animals also remain in the nesting colonies.

Life expectancy is 20 years and more. The maximum age is around 90 years. The ages confirmed by the recovery of ringed animals are 43 years and 10 months as well as 36 years and 9 months for birds from the British Isles and 19 years and nine months for a bird ringed on Heligoland. The average life expectancy is 34 years, but there are often ages over 60 years.

Systematics

External system

The fulmar belongs to the subfamily of seagull petrels (Fulmarinae), which form a monophyletic group. They are grouped together based on typical features of their skull and particularly large nasal tubes.

The fulmar is significantly different from shearwater , although it is closely related to the shearwater species Puffinus .

The closest relative within the genus is the silver petrel ( F. glacialoides ), which colonizes the southern oceans.

Internal system

DNA studies show that fulmars from Atlantic Canada are mainly descended from birds from Greenland , Iceland and the British Isles . While there is an extreme variety of haplotypes there, there is only a small selection on Saint Kilda , which indicates isolation through distance.

The fulmar has three subspecies. The North Atlantic subspecies of Fulmarus glacialis tend to have heavier and more compact skulls and beaks, although narrow and short beaks (Greenland) are also found. High Arctic populations of the nominate form Fulmarus glacialis glacialis have smaller beaks, especially those from Baffin Island . Birds of both variants have been found in Nova Scotia . The distinctly slimmer Pacific subspecies Fulmarus g. rodgersii has a narrower beak and a less robust skull.

The Atlantic subspecies Fulmarus g. minor (Baffin Island) is recognized by ITIS, but not by other sources, as they are part of the nominate form . The predominantly boreal subspecies Fulmarus g. auduboni (larger beak) is not recognized by ITIS, but by the other sources mentioned above. The Pacific subspecies Fulmarus g. glupischa is no longer recognized.

Inventory and inventory development

The fulmar originally lived in the far north. The northernmost lake colony is on the northern tip of Greenland , near the pack ice border . In the past hundred years it has expanded its breeding area further south and multiplied rapidly. The fulmar first reproduced in Iceland around 1750 . In 1839 he reached the Faroe Islands and in 1878 the Shetland Islands . He then settled on the British and Irish islands, where there were cliffs. The fulmar was sighted for the first time in France in 1935 . They have been breeding on Heligoland since 1972 . There the population is steadily increasing. In 1996 there were 53 breeding pairs there, in 2001 there were 92 breeding pairs and in 2006 the number of pairs rose to 120. The total population is estimated at one million specimens.

The reason for the increase in the population is attributed, among other things, to the preferred diet of dead fish. The spread is thus attributed to the development of the whaling industry in northern waters and to the fact that ships have released worthless whale advice into the sea. This new and abundant source of food was preserved after the decline in whale catches due to the development of the fishing industry , as the fish on the ships were gutted and the leftovers thrown overboard.

Researchers have found that the massive spread of this species can only be explained by successful reproduction in the new colonies. This resulted in an extremely rapid reproduction of these animals in North America , which resulted in a migration across the North Atlantic. As a result, the number of birds in Europe continued to increase.

Fulmar and human

In the time of the Vikings , the fulmar was an important source of food. It is believed that they caught the young birds before they were fully fledged. Bones have been found along with items from the 9th century on the island of Saint Kilda on the Scottish coast. Carl von Linné called this bird the "gray petrel" and in 1761 gave it the Latin name Procellaria glacialis .

In 1900, the population in Iceland was so large that the locals there would catch 60,000 young birds a year to eat. The fulmar was a major reason for some North Atlantic island communities to settle there. On Saint Kilda, residents hunted 10,000 young birds per year from 1829 to 1911, which is an average of 115 birds per capita. The hunted birds served as food supplies for humans in winter. The fulmar eggs are still eaten in some areas today.

Although the strong fulmar odor seeped into their homes (and stayed there for at least 20 years after the buildings were abandoned), the birds provided some products to people. The eggs and meat were eaten, the stomach oil collected and burned in lamps, feathers used for beds, hooks made of bones, and cadavers used as bait.

Fulmars like to follow fishing boats and fight for the trash. Seafarers know that they will have to be patient when they see these birds before they can reach land. On the other hand , if they see seagulls , they know that they are close to land.

The fulmar is a strictly protected species in Germany in accordance with Section 10 (2) No. 5 and No. 11 BNatSchG .

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d J. Fisher: The Fulmar. Collins, London 1952.

- ↑ AllAboutBirds: Northern Fulmar

- ↑ What Bird: Northern Fulmar Dark Morph

- ↑ Northern Fulmar. ( Memento from October 7, 2007 in the web archive archive.today ) at: identify.whatbird.com

- ^ A b c Finn Salomonsen: The Geographical Variation of the Fulmar (Fulmarus glacialis) and the Zones of the Marine Environment in the North Atlantic. In: The Auk. Vol. 82, 1965, pp. 327-355. sora.unm.edu (PDF)

- ↑ a b c Rolf Stange: Spitzbergen | Svalbard . Ed .: Rolf Stange. 5th edition. Spitzbergen.de, 2015, ISBN 978-3-937903-24-8 , pp. 560 .

- ↑ direct spectrum: plastic waste threatens North Sea birds

- ↑ Status report on the North Sea shows need for action Olaf Lies: The federal government should campaign internationally for tracking devices on dangerous goods containers. In: Environment.niedersachsen.de . January 8, 2019, accessed January 14, 2019 .

- ↑ John P. Dumbacher, S. Pruett-Jones: Avian chemical defense. In: V. Nolan Jr, ED Ketterson (Eds.): Current Ornithology. Volume 13, Plenum Press, New York 1996, ISBN 0-306-45473-4 , pp. 137-174.

- ^ A b J. Warham: The petrels: their ecology and breeding systems . Academic Press, San Diego 1990.

- ↑ PJ Weldon, JH Rappole: A survey of birds odorous or unpalatable to humans: possible indications of chemical defense. In: Journal of Chemical Ecology. 23 (11), 1997, pp. 2609-2633.

- ↑ a b c J. Warham: The incidence, functions and ecological significance of petrel stomach oils. In: Proceedings of the New Zealand Ecological Society. 24, 1977, pp. 84-93.

- ↑ a b C. Swennen: Observations on the effect of ejection of stomach oil by the fulmar Fulmarus glacialis on other birds. In: Ardea. 62, 1974, pp. 111-117.

- ^ J. Warham, R. Watts, RJ Dainty: The composition, energy content and function of the stomach oils of petrels (Order Procellariiformes). In: Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology. 23, 1976, pp. 1-13.

- ^ J. Jacob: Stomach oils. In: DS Farner, JR King, KC Parkes (Eds.): Avian Biology. Volume VI, Academic Press, New York 1982, pp. 325-340.

- ^ J. Fisher: The Fulmar . Collins, London 1952.

- ↑ Kerri M. Skinner: Oil-spitting in fulmars: an example of chemical defense in birds? EN 570: Chemical Ecology, 1998. Weblink ( Memento of August 1, 2011 in the web archive archive.today )

- ↑ K. Hüppop, O. Hüppop: Atlas for bird ringing on Helgoland. In: Vogelwarte. 47, 2009, p. 213.

- ^ W. Fiedler, O. Geiter, U. Köppen: Messages from the ringing centers. In: Vogelwarte. 49, 2011, p. 35.

- ↑ M. Wink, P. Heidrich, U. Kahl, I. Swatschek, HH Witt, D. Ristow: Inter- and intraspecific variation of the nucleotide sequence of the cytochrome b gene in Cory's (Calonectris diomedea), Manx Shearwater (Puffinus puffinus ) and the Fulmar (Fulmarus glacialis). In: Journal of Nature Research C . 48, 1993, pp. 504-509 ( PDF , free full text). PMID 8363711

- ↑ TM Burg, J. Lomax, R. Almond, M. de L. Brooke, W. Amos: Unraveling dispersal patterns in an expanding population of a highly mobile seabird, the northern fulmar (Fulmarus glacialis) . The Royal Society, March 25, 2003. PMC 1691321 (free full text)

- ^ Birds of Nova Scotia: Northern Fulmar. ( Memento from July 10, 2012 in the web archive archive.today )

- ↑ TM Burg, J. Lomax, R. Almond, Mde L. Brooke, W. Amos: Unraveling dispersal patterns in an expanding population of a highly mobile seabird, the northern fulmar (Fulmarus glacialis). In: Proc Biol Sci. Vol. 270 (1518), 2003, pp. 979-984. PMID 12803914

- ↑ ITIS Report: Fulmarus glacialis (Linnaeus, 1761)

- ↑ Avibase Database: Fulmar (Fulmarus glacialis) (Linnaeus, 1761)

- ↑ Skulls Fulmars. ( Memento from September 26, 2007 in the web archive archive.today )

- ^ WWF: Nature Library. Nature in Germany. 4. Life on the coast and the sea. Weltbild Verlag, 2006, ISBN 3-89897-445-6 , p. 38 (-41, 45).

literature

- Einhard Bezzel : FSVO manual birds. BLV Buchverlag, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-8354-0022-3 .

- Michael Brooke: Albatrosses and Petrels across the World. Oxford University Press, 2004, ISBN 0-19-850125-0 .

- J. Fisher: The Fulmar. Collins, London 1952.

- KC Hamer, J. In Steele, S. Thorpe, K. Turekian: Birds: Procellariiformes. Encyclopedia of Ocean Sciences. Academic Press, London 2001, ISBN 0-12-227430-X .

- KC Hamer, DR Thompson: Provisioning and growth rates of nestling fulmars Fulmarus glacialis: stochastic variation or regulation? In: Ibis. 139, 1997, pp. 31-39.

- Josep del Hoyo et al: Handbook of the Birds of the World. Volume 1: Ostrich to Ducks. Lynx Edicions, 1992, ISBN 84-87334-10-5 .

- DN Nettleship, RD Montgomerie: The northern fulmar, Fulmarus glacialis, breeding in Newfoundland. In: Amer Birds. 28, 1974, p. 16.

- RA Phillips, KC Hamer: Growth and provisioning strategies of northern fulmars Fulmarus glacialis. In: Ibis. 142, 2000, pp. 435-445.

- RA Phillips, KC Hamer: Postnatal development of northern fulmar Fulmarus glacialis chicks: is growth limited by food provisioning or internal constraints? In: Physiological & Biochemical Zoology. 73, 2000, pp. 597-604.

- R. Stange: Spitzbergen | Svalbard. Arctic natural history in words and pictures. Backgrounds | Routes & Regions | Practical. Spitzbergen.de-Verlag, 5th edition, May 2015.

Web links

- Videos, photos and sound recordings of Fulmarus glacialis in the Internet Bird Collection

- Entry at round birds

- Entry on Birdguides

- Entry with New England Seabirds

- Fulmarus glacialis inthe IUCN 2012 Red List of Threatened Species . 2. Listed by: BirdLife International, 2012. Retrieved November 17, 2012.

- Fulmar's feathers

- Video: Fulmarus glacialis (Procellariidae) - landing on breeding rock . Institute for Scientific Film (IWF) 1970, made available by the Technical Information Library (TIB), doi : 10.3203 / IWF / E-1619 .