Pitcairn

| Pitcairn Island | |

|---|---|

| Pitcairn, satellite image | |

| Waters | Pacific Ocean |

| Archipelago | Pitcairn Islands |

| Geographical location | 25 ° 4 ′ 12 ″ S , 130 ° 6 ′ 25 ″ W |

| length | 3.5 km |

| width | 1.8 km |

| surface | 4.5 km² |

| Highest elevation | Pawala Valley Ridge 347 m |

| Residents | 50 (2020) 11 inhabitants / km² |

| main place | Adamstown |

| Map of Pitcairn | |

Pitcairn is the main island of the Pitcairn Islands ( English Pitcairn Islands ) and is located in the Pacific , about 5000 km from New Zealand and about 5400 km from South America . It is the only inhabited island in the archipelago . Other islands in the group are Oeno with its tiny Sandy Island , Henderson and the Ducie Atoll . In the Creole language, Pitcairn English , it is called Pitkern .

Pitcairn was discovered on July 2, 1767 by the midshipman Robert Pitcairn, son of the naval officer John Pitcairn , and has been a British crown colony or British overseas territory since 1838 . The Pitcairn Islands are the last British colony in the Pacific.

The inhabitants of the main island are in part descendants of the mutineers of the Bounty and their Polynesian wives. The first sustainable women's suffrage was introduced here in 1838 .

geography

The 4.5 km² island is isolated in the South Pacific. The closest inhabited islands are Easter Island in the east, 2000 km away, and in the west, the Gambier Islands , 500 km away.

Pitcairn is the remnant of a geologically young shield volcano , consisting of alkali olivin basalt , hawaiite , mugearite and trachyte . Today's island was formed in several eruption phases between approximately 0.93 million and 0.45 million years BP . In contrast to many other islands in the South Pacific, the surrounding coral fringe is missing , so that strong surf reaches the unprotected coast. The island base is narrow and drops abruptly to depths of over 3000 meters. The island's steep cliffs rise directly from the sea, there is no coastal plain or beach. Above that there is a strongly profiled plateau with the populated and cultivated areas. The highest point, Pawala Valley Ridge , is 347 meters above sea level.

Volcanic slag is what gives the soil its striking red color. The earth is fertile and the humid, subtropical climate with abundant rainfall favors lush growth. The amount of precipitation is around 1700 mm annually, about two to three times as high as in Germany; the monthly precipitation show considerable seasonal differences. In some summers, longer dry periods can occur. Depending on the season, temperatures are between 13 and 28 ° C.

All year round flowing streams, rivers and lakes are missing, so that the inhabitants are dependent on cisterns for water supply . In the meantime there has also been an attempt to drill for groundwater.

The only settlement is Adamstown , on the high plateau above Bounty Bay, where all the island's residents live.

Flora and fauna

flora

Large areas of Pitcairn are shaped by human intervention, bushy and covered with non-native flora. Other areas are laid out as agricultural cultivated areas and large areas of rose apple ( Syzygium jambos ) are planted, an evergreen myrtle bush that originally comes from Asia and can be up to 15 meters high. Native vegetation now covers less than 30 percent of the surface, mostly steep slopes and remote valleys. An investigation by staff of the Botanical Institute of Trinity College in Dublin from 2002 leads 81 domestic (including 10 endemic ), but 250, introduced by the human species of plants. 18 species are among the world's most threatened. The native flora of Pitcairn originally comes from south-east Polynesia, but due to its isolated location and the relatively young geological age of the island it is rather underdeveloped compared to that of other Polynesian islands .

The remnants of the local forest - which can be counted among the subtropical mountain cloud forests - are dominated by the endemic tree Homalium taypau , called Sharkwood Tree by the islanders , because the wood can be used to make carvings (sharks and dolphins). In remote, shady valley cuts, there is extensive vegetation with ferns . Endemic and meanwhile very threatened is Ctenitis cumingii, a member of the worm fern family ( Dryopteridaceae ) .

Another endemic plant is the composite flowers scoring ground cover Bidens mathewsii which mainly grows in the cliffs of the southeast coast.

In the north and east of the island, the bushy areas are interspersed with hibiscus and pandanus trees , the leaves of which are processed by the islanders into all kinds of wickerwork.

Cultivated plants include coconut palm , pineapple , citrus plants , banana , papaya , melon , guava (which has since been released into the wild), sugar cane , yams , taro , sweet potato and breadfruit .

fauna

The original fauna on land is limited to insects , snails and small reptiles . All other animals were introduced by humans. Since it was released into the wild and is no longer kept under controlled conditions as a food animal, a major plague has been the Pacific rat ( Rattus exulans ) introduced by the first Polynesian settlers . There are no dangerous animals or disease carriers for humans. The pigs that have been kept on the island since the mutiners colonized it were exterminated after Seventh-day Adventists , who consider pigs unclean, proselytized the islanders and baptized all of the residents at the end of 1890 .

Pitcairn has an interesting but not very diverse bird life. The Pitcairn's reed warbler ( Acrocephalus vaughani ), a land bird that belongs to the passerine birds and is endemic to Pitcairn, is both unique and threatened .

Numerous species of seabirds nest in large populations, especially on the offshore steep cliffs. A full inventory is still pending.

Due to the lack of a coral fringe, deep sea fish and reef dwellers predominate in the vicinity of Pitcairn. The irregularly appearing island newspaper "The Pitcairn Miscellany" lists meticulously which and how many fish the residents have caught. These include mainly sharks , sea bream , barracudas , red snapper , tuna and the occasional marlin . There is lobster and lobster on the shelf . Once a year humpback whales pass by on their migration through the Pacific.

history

prehistory

The prehistory of Pitcairn is largely in the dark. Today it is believed that Pitcairn was settled around 1000 AD from the northwestern island of Mangareva as part of the Polynesian expansion to the east. The legend of Mataki-te-rangi is told on Mangareva , an island in the south-east, which was colonized by the chiefs and planted with breadfruit trees. On entering Pitcairn Island in 1790, the mutineers from the Bounty actually found numerous breadfruit trees. The essential evidence of an earlier settlement by Polynesians, however, are carefully crafted stone tools made of black basalt , which are still occasionally found in the fields and are exhibited in the small museum in Pitcairn.

When the mutineers of the Bounty entered the island, traces of the indigenous people were still visible, including statues that, although less skilfully worked, were described as somewhat similar to sculptures from the Marquesas and Easter Island . The British explorer Frederick William Beechey was able to find remains of it when he visited Pitcairn in 1826 as part of a South Sea expedition. He writes about it:

“To the left of 'The Rope' is a hill of considerable height that towers over Bounty Bay [probably meaning St. Pauls Point]. Upon their arrival on this hill, the mutineers found four statues about six feet high on a platform, which - according to Adams' description - were not unlike the moais of Easter Island, but were much smaller. One of these statues, the only one still standing, was a rough image of a human up to the waist and carved out of a single piece of red lava. We were told that human bones and stone axes were occasionally unearthed near these figures, but we could only find two bones which we believed to be able to infer the stature of the indigenous people. These were a femur and part of a skullcap of unusual size and thickness. The stone axes, of which we found several specimens, were made from a compact basalt lava [which,] not unlike phonolite, is very hard and [is] well suited for polishing. "

The Belgian businessman and ethnologist Jacques-Antoine Moerenhout , who had the opportunity to speak to John Adams , the last surviving mutineer, apparently describes the same ceremonial platform, albeit in a much more dilapidated state:

“I reached the place where the temple was built and where the people, whose traces have now been blurred, worshiped their gods, about whom we no longer know anything. I saw nothing that convinced me that anything had been there in the past, except the remainder of a statue, a three and a half foot bust [approx. 1.20 m] length, whose facial features were barely visible, but whose head, shoulders and body were well proportioned. There was also a pile of stones, but nothing left any indication of where the 'marai' [ceremonial platform] was once built. "

Moerenhout also reports that he learned from conversations with the residents of Pitcairn that a skeleton had been found on the now destroyed platform, the skull of which was bedded on the shell of a large pearl oyster (which does not appear on Pitcairn). In addition, stone house foundations and stone-lined earth ovens were found on the island.

Katherine Routledge , who visited Pitcairn in August 1915, reports a total of three marae on Pitcairn. One of them, the remains of which she was able to find, was on St. Paul's Point on the east coast, a significant hill overlooking Bounty Bay. She describes the facility as an earthfill 4 m high, to which a rising earth ramp, 11 m long, clad with large beach pebbles, led. In this respect, there is a comparability with designs on Easter Island. According to the residents' reports, three stone statues should originally have stood on the platform.

In 1934/35 a Franco-Belgian expedition led by Alfred Métraux , who came from Easter Island, stayed on Pitcairn. The Belgian archaeologist Henri Lavachery , a member of this expedition, examined "Down-Rope", a bay in the south of the island with a deposit of obsidian used by the indigenous peoples , rock carvings depicting animals, people and graphic symbols. The petroglyphs in this inaccessible place, the name of which indicates that you had to abseil to get there, can still be found today. Lavachery also explored three locations of ceremonial platforms given to him by the islanders. However, only minor traces of the structures were visible. But under Norris Young's house he found a statue, a headless fragment 79 cm high and 30 cm in diameter made of porous tufa , which Young used as a support for the floor. The human torso ends below the navel , similar to the moai on Easter Island. The two oversized hands cover the abdomen , which also parallels the statues on Easter Island. Young had found the figure at the foot of the cliffs in Bounty Bay. It probably belonged to one of the ceremonial platforms described by Moerenhout and Routledge, which has since been destroyed. The sculpture is the only surviving sculptural work of the Pitcairn Islands' indigenous people and is now in the Otago Museum, Dunedin , New Zealand .

On the basis of the available reports it cannot be determined how many stone statues there were originally on Pitcairn. Lavachery guessed three or four. The archaeologist Arne Skjølsvold , who came to Pitcairn in 1956 with the "Norwegian Archaeological Expedition to Easter Island and the Eastern Pacific" from Thor Heyerdahl , assumes that there were originally significantly more.

The archaeologist Marshall Weisler from the University of Otago in New Zealand has established trade links between Mangareva, Pitcairn and Henderson in the course of recent research. His research shows the export of oyster shells for making jewelry and fishhooks from Mangareva to Pitcairn and Henderson on the one hand and the import of stone tools from Pitcairn and probably bird feathers and sea turtles from Henderson on the other. The densely populated Mangareva may have been the hub for this triangular trade, which also included the Tuamotu and Austral Islands . The trade relations ended around 1450 AD, the reasons for this can no longer be determined. The evolutionary biologist Jared Diamond suspects in his book Collapse a man-made ecological catastrophe on Mangareva as the cause; Weisler and Walter cite social tensions caused by overpopulation and lack of resources as reasons. Pitcairn was probably abandoned during the 17th century; when the island was first visited by Europeans, it was already uninhabited.

Discovery story

The first European ship to reach Pitcairn was the HMS Swallow under Captain Philipp Carteret in 1767 . He named the island after the midshipman Robert Pitcairn, who first sighted it.

“We continued our course westward until the evening of July 2nd when we discovered land to the north of us. When we approached the next day, it looked like a huge rock rising straight out of the sea, no more than five miles in circumference and apparently uninhabited. The rock was overgrown with trees, and we saw a narrow trickle of fresh water running down the side into the sea. I wanted to land, but the surf, which was particularly heavy at this time of year, made it seem impossible. I sailed a little less than a mile from the coast to the west side of the rock, there is sand and coral bottom at 25 fathoms . It is likely that when the weather is calm, landing here will not only be possible, but easy. We saw a multitude of seabirds prowling over the rocks, and there should be good fishing grounds about a mile from the coast. It is located at 20 ° 2 ′ south latitude and 133 ° 21 ′ west longitude and about 1000 leagues west of the American continent. It is so high that we could see it from 15 leagues away, and since the rock was first spotted by a young gentleman, son of Major Pitcairn of the Marines, who unfortunately went down with the Aurora , we named it PITCAIRN'S ICELAND. When we were near this island, the weather was extremely stormy, with long waves rolling in from the south, higher than anything I had seen before. "

The position given by Carteret is imprecise in terms of both latitude and longitude. As a result, the island was shown on the nautical charts, but far from its actual position.

James Cook had read Carteret's log and intended to find the island on his second expedition to the South Seas in 1773. However, the occurrence of scurvy on the escort ship Adventure prevented a lengthy search, and Cook went directly to Tahiti instead .

The mutineers of the Bounty

Fletcher Christian , the leader of the mutiny, also knew Carteret's report and thought the island was a suitable haven from the British ships the Admiralty would send to arrest the mutineers. The nine Europeans, six Polynesian men and twelve Polynesian women sighted the rocky island on January 15, 1790. The eight British who accompanied Christian were the midshipman Edward "Ned" Young, the sailors John Adams alias Alexander Smith, Isaac Martin, William McCoy, John Mills, Matthew Quintal, John Williams and the second gardener William Brown. However, due to the strong surf, they could only land in a dinghy three days later.

Christian explored the island with two companions for two days and found it uninhabited but habitable. There were coconut palms and breadfruit trees, and he found evidence of previous Polynesian settlement. Pigs, goats, chickens, yams and sweet potatoes were carried on the bounty . He found the only suitable landing site for the Bounty in what is now Bounty Bay . Equipment and usable ship parts were brought ashore in the following two days. Today's Adamstown emerged from the settlement that the mutineers built above Bounty Bay on the first day.

After lengthy debates, the seaman Matthew Quintal set fire to the ship on January 23, 1790 of his own accord in order to rule out a discovery. The coexistence of the settlers was based on the values of the Europeans, which caused conflicts from the start. Every European had a companion; the six Polynesians had to share the remaining three women and were treated more like slaves.

When the wife of the blacksmith John Williams died and he appropriated one of the three Polynesian women, the conflict escalated. On September 20, 1793, the Polynesians killed Williams and three other mutineers, and on October 3, they murdered Fletcher Christian. This act led to further acts of revenge. Soon all Polynesian men and one woman were killed. In 1794 only Young, who had since taken over the management, were still alive, Adams, Quintal, McCoy, ten women and their children.

The Scot McCoy began to make brandy from the sugary root of the club lily ( Cordyline fruticosa , Polynesian: ti ; the Polynesians made the tattoo ink from the burned leaves of this plant), became addicted to alcohol and died if he fell off the cliffs. After the alcohol-addicted, violent Quintal threatened to kill all the children, Young and Adams eliminated him together in 1799.

When Edward Young died of asthma on December 25, 1800 , John Adams was the only adult man left, along with ten Polynesians and now 23 European children. The Polynesian men had left no offspring. Shortly before his death, Young had taught the uneducated Adams to read from the Bounty's ship's Bible. Adams read the Bible daily, began a godly life, banned alcohol, and held regular services. On March 5, 1829, he died of natural causes as the respected head of the small community.

The Admiralty had sent the frigate HMS Pandora under Captain Edward Edwards in November 1790 to track down and arrest the mutineers. On the outward journey, Edwards came close to Pitcairn Island, but did not see it. He sailed to Tahiti and captured all fourteen Bounty crew members who were still there . On the return voyage, the ship crossed the Polynesian Islands further west in the unsuccessful search for more mutineers. On the Great Barrier Reef , off the northeast coast of Australia, the Pandora struck a coral reef in August 1791 and sank. Four of the prisoners drowned, the ten surviving men of the Bounty reached Timor in September and were brought from there to Portsmouth , where they were tried in September 1792. Three were hanged, the others acquitted or pardoned.

Rediscovery

Pitcairn was rediscovered by Mayhew Folger , an American seal hunter , who on his ship Topaz on February 6, 1808 sighted an island that was not supposed to exist in this position. From the description, he suspected that he had discovered Carteret's Island. However, he was amazed at the smoke on the island described as uninhabited. When the Topaz anchored in Bounty Bay, three young islanders rowed to the ship, who told followers in English that they were descendants of the Bounty mutiners. Folger was a guest in the 35-person colony for a few days and had long conversations with Adams. As a parting, Adams gave him the Bounty's compass and Kendall chronometer . Folger's report, which he sent to the British Admiralty on his return, met with little interest there because of the Napoleonic Wars .

Incorporation into the United Kingdom

On September 17, 1814, the two warships HMS Briton and HMS Tagus arrived off Pitcairn. Unaware of Folger's discovery six years earlier, Captains Staines and Pipon were impressed by the peaceful and godly fellowship they found. Adams volunteered to sail back to England and face the judge of the sea, but the residents begged the captains to leave him on the island. In his later report to the Admiralty, Staines wrote that it would have been an act of great cruelty to capture the last surviving mutineer.

There were further visits in the following years. Whalers took advantage of the opportunity to get fresh vegetables. In the reports that appeared sporadically in the press, the isolated community was romanticized and therefore pious donors provided Bibles, hymn and prayer books, but also household items and tools. In 1823 the ship's carpenter John Buffet was the first new settler to stay on the island after the mutinies; In 1828 came George Nobbs, allegedly the illegitimate son of a marquis who established himself as a preacher. In March 1831, all residents were evacuated to Tahiti. After several Pitcairners, including Fletcher Christian's son Thursday October, had died of infectious diseases there, 65 survivors returned to their isolated island in September 1831.

In October 1832, the American adventurer Joshua Hill landed on Pitcairn, pretended to be the British government's envoy and was proclaimed president of the small community. As a result, he exercised a dictatorial rule over the islanders and imposed harsh penalties for even minor offenses. After it was revealed that his claim to represent the British government was untrue, Hill had to leave the island and was deported to Valparaíso on a Royal Navy ship in 1837 .

Because of this experience and because of the increased attacks by whalers who landed on the island, the residents sought the protection of the British crown. With the help of the captain of the British Sloop Fly , Russell Elliott, they drafted a constitution for the island community, which was signed on November 30, 1838 on board the Fly . With the British Settlements Act of September 16, 1887, Pitcairn was also made subject to the British Kingdom de jure .

Emigration to the Norfolk Island

In 1856 Pitcairn already had 194 inhabitants, and the trend is increasing. Since after several natural disasters one had to fear that the island community, which had grown considerably in the meantime, could no longer feed itself, the island was evacuated again in 1856. This time were westernmost, residents on the 6000 km today Australia is part of Norfolk Island accommodated.

In January 1859, 16 emigrants returned under the leadership of Moses and Mayhew Young, and in 1864 four more families followed. The rest of them stayed on the island of Norfolk. Today a third of the local population consists of their descendants.

The very pious Pitcairnes had eagerly read the scriptures sent to them by the Seventh-day Adventists , and in 1886 the Adventist missionary John I Tay spent five weeks on the island. Therefore, an American mission ship arriving in 1890 was very welcome, and the economic support that went with the mission was certainly no less. All the residents were baptized, and their descendants are still Adventists today.

At the beginning of the twentieth century there was already a newspaper, school and kindergarten on the island thanks to worldwide donations from Adventists.

20th century

With the opening of the Panama Canal in 1914, the isolation ended because Pitcairn was on the shipping route to New Zealand . A ship visited the island almost every week. During World War II, the British Navy stationed radio monitors on Pitcairn. After the Second World War, the interests of Great Britain slackened, so that - in the absence of a port and an airport - a relative isolation set in again. Today Pitcairn is called at an average of four to six times a year by a container ship that brings the essential goods and mail. Occasionally a cruise ship also comes to visit.

Population development

Pitcairn has had a population of 50 to 60 people since the 1980s. The most meaningful sources on the island's particular demography are the census data.

- 1790: 27

- 1800: 34

- 1808: 36

- 1825: 66

- 1831: 65

- 1839: 106

- 1844: 119

- 1850: 106

- 1856: 194

- 1859: 16

- 1864: 43

- 1873: 70

- 1875: 85

- 1878: 90

- 1879: 90

- 1864: 43

- 1884: 105

- 1888: 112

- 1889: 127

- 1893: 136

- 1894: 130

- 1896: 132

- 1897: 142

- 1898: 142

- 1900: 136

- 1901: 126

- 1905: 169

- 1906: 104

- 1907: 160

- 1908: 150

- 1912: 148

- 1914: 165

- 1916: 163

- 1933: 190

- 1936: 200

- 1937: 233

- 1943: 163

- 1956: 161

- 1959: 143

- 1961: 126

- 1966: 96

- 1976: 74

- 1979: 61

- 1982: 55

- 1985: 58

- 1986: 68

- 1987: 59

- 1988: 55

- 1989: 55

- 1990: 59

- 1991: 66

- 1992: 54

- 1993: 57

- 1994: 54

- 1995: 55

- 1996: 43

- 1997: 40

- 1998: 66

- 1999: 46

- 2000: 51

- 2001: 44

- 2002: 48

- 2003: 59

- 2006: 65

- 2007: 64

- 2008: 66

- 2011: 67

- 2012: 48

- 2013: 49

- 2016: 54

- 2017: 49

- 2018: 50

- 2019: 50

Pitcairn today

politics

The Pitcairn Islands are the last British overseas territory in the South Pacific. The residents are British citizens ( British Overseas Territories Act 2002 ). Although the United Kingdom would like to change the status for reasons of cost, the residents have been successfully resisting it for years, as their stay on the island is only guaranteed with British support. The role of Governor of Pitcairn has been exercised by the British High Commissioner in New Zealand since 1970 . This position was previously held by the British High Commissioner for the Western Pacific (1898 to 1952) and the Governor of Fiji (1953 to 1970).

The city council and a mayor administer the Pitcairn Islands internally. From November to December 2004, a woman, Brenda Christian, administered the island for the first time as an interim solution. As of 2013, Shawn Christian was elected mayor. The legislature is formed by the Island Council, which also has judicial powers. It consists of ten people, four of whom are directly elected. The Auckland- based Pitcairn Islands Office acts as a link between the island's government and the governor . The PIO is headed by a commissioner appointed by the governor.

The mayor, who is in his second term in 2018, is Shawn Christian, a direct descendant of Fletcher Christian, who was convicted of the sexual abuse of minors.

economy

Pitcairn residents mostly import their groceries and essentials from New Zealand and buy them from visiting cruise lines when possible. Most of the food is kept in freezers and cabinets by the residents, a large number of which each household has, depending on the number of people, connected to the mains. These often old, partially defective freezers and cabinets represent the greatest strain on the local power grid and the income of the families. The diet is very much based on British and North American cuisine, i. H. deep fried, high in fat and sugar.

The jobs in the local administration are the main source of income for the population. Another profitable activity is selling low value handcrafted souvenirs, t-shirts and the like to cruise tourists. The Pitcairn Island Producers Cooperative ( PipCo for short ) sells island products such as honey, propolis tincture , soap, carvings and T-shirts made in the Far East and printed on Pitcairn via its online shop . In particular, the program launched in 1998 to promote beekeeping was successful; the sale of honey generates annual revenues of approximately NZ $ 200,000.

Tourism offers other employment opportunities. Around twelve cruise ships stop at Pitcairn every year, around half of which allow their passengers to take a trip to the island. Conversely, islanders go on board the cruise ships to sell their goods there. Some Pitcairners offer private accommodation for vacationers. The opportunities for development in tourism are limited because of the island's remoteness, the long and costly journey and the small number of attractions and activities.

Until the first half of the 1990s, Pitcairn was able to cover its financial needs from its own resources. High profits were made from the sale of collector's stamps; the generated surpluses flowed into the Pitcairn Island Investment Fund , whose income was sufficient to finance the costs of the island administration. From 1993 onwards, falling interest rates and capital withdrawals to cover budget deficits reduced this income, and in 2004 the fund had to be liquidated due to exhaustion. Profits from the sale of postage stamps have also fallen sharply, as shrinking sales and rising costs reduce profitability. Since at the same time the costs for public services and infrastructure (especially the charter fees for the vital ship connection) have risen sharply, Pitcairn can currently only generate a fraction of its budget itself and is dependent on budget support from the United Kingdom. The development of new sources of income has so far not been very successful; the income from the landing fees of the tourists, the coin trade and the marketing of the top-level domain .pn only cover a small part of the deficit. Tax revenues are minimal as Pitcairn citizens do not pay income tax or customs duties. In the 2015/16 financial year, self-generated income of around NZ $ 1.4 million (€ 850,000) was offset by subsidies of around NZ $ 6.5 million (€ 3.9 million).

Infrastructure

In the absence of year-round flowing water, Pitcairn has no central fresh water supply. Supplies are stored in cisterns, the houses have water tanks. A borehole has proven a fresh water supply, which however turned out to be not very productive. The installation of flush toilets in 2003, particularly public ones for the needs of the occasional cruise tourist, was perceived by residents as a major step forward.

Power is supplied by three diesel generators. The attempt to install a wind turbine was abandoned in 2013 after incurring significant costs without actually building.

The houses are connected to an island telephone in the VHF network. The installation of an international earthquake control station with the necessity of constant data transmission meant that worldwide e-mail and telephone communications are also possible via Inmarsat . The island's radio station operates official radio communications , but there are also amateur radio links on shortwave with Pitcairn.

The only paved road on the island has been the concrete path leading from the landing site up the Hill of Difficulties to Adamstown since 2005. The main means of transport are quads and motor tricycles , which are already used by the children.

Pitcairn has neither a port nor an airport. From time to time the construction of an air runway is discussed, but so far without concrete implementation. The entire supply is carried out by cargo ships, usually container ships in traffic between New Zealand and the Panama Canal. Since 2009 the Claymore II has been chartered for regular supply trips from New Zealand to Pitcairn and for ferry connections between Mangareva ( Gambier Islands ), 500 kilometers away , where a small regional airport is located, and Pitcairn . The ships are in the roadstead and the goods are transferred in often dangerous maneuvers with the two approximately twelve-meter-long aluminum workboats (longboats) of the Pitcairner. With funds from Great Britain and the EU, the boat landing site (The Landing) in Bounty Bay was renovated and expanded in 2005 as part of the improvement of the infrastructure . In addition, the Tedside bypass jetty on the western side of the island with a concrete riverside path and a new access road was put into operation.

The island school in a building that was newly built in 2006 is quite progressively equipped with a computer, video and DVD player. The teacher is hired for one year and is mostly from New Zealand. Children who have reached the age of twelve are sent to New Zealand to complete secondary education. They can then complete further training or attend university.

A few years ago the infirmary was modernized. The building below the village, which was newly constructed in the mid-1990s, houses a treatment room with X-ray equipment, a dental treatment room, a laboratory and medicine depot, as well as a hospital room. The British administration has tried to keep a general practitioner on the island at all times since 2004, which has improved health care significantly. Mostly British, New Zealand or Australian doctors are posted to Pitcairn for one to two years and are employed there by the Pitcairn Island Office. Some Pitcairners have trained as nurses. A particular health problem on the island is the incidence of diabetes mellitus . The reason for this is probably the combination of genetic predisposition and obesity, caused by an unhealthy, high-fat diet and a pronounced lack of exercise.

In a cooperatively operated shop, the islanders can buy goods that they cannot manufacture themselves. However, the supply is very limited, especially if the supply ship could not be unloaded due to unfavorable weather.

tourism

The remote and undeveloped Pitcairn is difficult to reach. The supply ships from New Zealand run irregularly and only take tourists with them in exceptional cases. Cruise ships visit Pitcairn several times a year, they lie in the roadstead in front of the island, and when the weather permits, the Pitcairn people come on board with their boats to sell souvenirs. Disembarking passengers is often too dangerous because of the strong surf, so that most cruise passengers have to be content with a circumnavigation of the island. Another way to get to the island is by chartering an ocean-going yacht in Tahiti or the Marquesas.

To enter the island, the permission of the magistrate is required, which is easily granted for cruise tourists, visitors who want to stay longer, but is usually denied after having had bad experiences with some dropouts in the past. There is a government guest house in Adamstown reserved for official visitors; other guests must stay privately.

The main attraction is probably the island itself with its inhabitants and the knowledge that you are one of the few people who have ever set foot in Pitcairn.

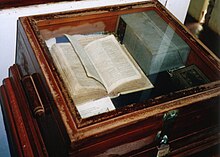

- In 2005 a small museum was set up. It shows finely crafted stone tools from the time of the Polynesian settlement, some relics of the Bounty , personal possessions of the mutineers, the ship's bible of the Bounty and a collection of the coveted postage stamps.

- Above Adamstown is Christian's Cave in a steep cliff, a shallow cave with an overwhelming view of the island and the sea. This is where Fletcher Christian is said to have withdrawn to look for British ships.

- On the northern edge of the village is the small cemetery, romantically weathered and overgrown with flowering creepers. Outside the cemetery, to the west of the village, is the grave of John Adams, who is buried next to his wives. It is the only surviving grave of a mutineer of the Bounty .

- The main square, a paved square in the center of the village, is framed by the church, the post office, the parish hall and the parish hall. An anchor and one of the bounty's four pounders are on display in front of the meetinghouse . Another cannon from the Bounty is in front of the Pitcairner Len Brown's house.

Last official figures from 2012 after 870 tourists visited the island.

The rape trial

In 1999, after rumors of rape and sexual abuse of minors, a British policewoman was sent to Pitcairn to investigate. After concrete allegations emerged, social workers were also brought in. The surveys led to criminal proceedings against seven of the then twelve adult men living on the island - including the incumbent mayor Steven Raymon (Steve) Christian. There were 55 indictments in total, dating back up to forty years.

The defendants initially fought for the right to have the trial held on the island instead of in New Zealand, as proposed by the British Parliament in 2002. In order to be able to hear witnesses from Norfolk and New Zealand via video transmission, the existing satellite transmission system was expanded. Further construction work was required, among other things, to cope with the doubling of the island's population during the seven-week negotiations. Most recently judges, court officials, police officers, defense lawyers and prosecutors were shipped to the island; six journalists also came. According to the New Zealand Press Association, the cost of the process was estimated at nearly $ 17 million on November 3, 2006.

The trial began on September 30, 2004. Defense lawyers argued that the island was not necessarily subject to British law; Sexual contact with minors corresponds to a customary law that has existed for more than 200 years.

On October 24, 2004, the court found the defendants guilty in 35 of the 55 cases examined. Two defendants who apologized to their victims during the trial were sentenced to 300 and 400 hours of community service, respectively. Four defendants were given three to six years' imprisonment. Only the former judge and later mayor Jay Warren was acquitted of the allegations. Defense counsel appealed, which was heard in the Supreme Court in Auckland , New Zealand, from April 18, 2005 , and dismissed on March 2, 2006. Most recently, the convicts called the British Privy Council (London), which finally rejected the applications in October 2006. In 2007, a prison was built for the convicts on Pitcairn, which is operated by guards from New Zealand.

Following the procedure, Britain and the European Union invested in the island. Telephone and internet connections were set up and the first paved road was built. In addition, a police officer, a social worker and a representative of the British government are now permanently on the island. Visiting children on the island was heavily regulated. Tourists are only allowed to bring children under the age of 16 to the island after prior coordination with the local administration. Officials working on behalf of the British Government are not allowed to take their children to the island for the duration of their employment.

Others

Until a few years ago, the Pitcairn people drove their two open aluminum boats (longboats) to the otherwise uninhabited island of Oeno , 140 kilometers away, to spend a few days of relaxation swimming and fishing, as there is no sandy beach on Pitcairn itself. For this purpose, several open, palm-leaf-roofed huts were built on Oeno for cooking and living. Due to a lack of maintenance and repairs, the longboats are in insufficient condition for ocean voyages. The most extensive loss of seafaring knowledge and skills has the consequence that trips outside the field of vision of the island are no longer possible.

In a political satire by Mark Twain , published in 1879 short story The Great Revolution in Pitcairn ( German A miniature empire in the ocean ), tells himself off the island population of the UK and calls a dodgy American from emperor.

language

Pitkern or Pitcairn English is the idiom spoken on the island to this day .

literature

- Caroline Alexander: The Bounty. The real story of the mutiny on the Bounty . Berlin Verlag, Berlin 2004, ISBN 3-8270-0163-3 .

- Dea Birkett: Snake in Paradise - my trip to the South Seas to the descendants of the mutineers on the Bounty . Albrecht Knaus Verlag, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-8135-0123-X (describes everyday life on the island from the perspective of an unpopular long-term visitor).

- Jared Diamond : Collapse - Why Societies Survive or Fall . S. Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2005, ISBN 3-10-013904-6 .

- Herbert Ford: Pitcairn Island as a port of call: a record, 1790-2010 . 2nd Edition. McFarland & Company, Jefferson, NC 2012, ISBN 978-0-7864-6604-7 (English, limited preview in Google Book Search - the author is the director of the Pitcairn Islands Study Center, Pacific Union College).

- Henri Lavachery : Contribution à l'étude de l'archéologique de l'Île de Pitcairn . In: Bulletin de la Société royale belge d'anthropologie et de préhistoire . tape 51 , 1936, ISSN 0304-1425 (French, results report of the Franco-Belgian archaeological expedition).

- David Marshall: Pitcairn. What became of the mutineers of the "Bounty" . 2nd Edition. Saatkorn-Verlag, Hamburg 1990, ISBN 3-8150-0815-8 .

- Robert Merle : The Island . 1st edition. Aufbau-Taschenbuch-Verlag, Berlin 2002, ISBN 3-7466-1221-7 (the story after the mutiny as a novel; first publication in French: 1962).

- Charles Bernard Nordhoff , James Norman Hall : The Mutiny on the Bounty - Volume 2: Sea Without Borders . Edition Maritim, Hamburg 2004, ISBN 3-89225-508-3 (the story of Pitcairn as a novel).

- Christian Schüle: The Parable of Pitcairn . In: mare . No. 58 . Mareverlag, October 2006, p. 104 ff . ( Text excerpt online ).

- Deborah Procter, Vincent Fleming (Eds.): Biodiversity: the UK Overseas Territories . Joint Nature Conservation Committee, Peterborough 1999, ISBN 1-86107-502-2 , 12: The Pitcairn Islands, pp. 88–95 (English, online [PDF; 733 kB ]).

- Reinhard Stegen: Mutiny on the Bounty. Pitcairn terminus. Documentary. kv Video, Grünwald 1997.

Web links

- The Government of the Pitcairn Islands. Pitcairn Government online portal.

- Country profile: Pitcairn Islands (British Overseas Territory). In: Foreign & Commonwealth Office: Travel & living abroad. The National Archives (archived November 12, 2009).

- Pitcairn Island. In: Pitcairn Islands Study Center. Pacific Union College (English).

- Karen Frankenstein, Ariane Huml: Pitcairn Island: Heirs to the Uprising. In: FAZ.Net . March 26, 2012.

- Julian McDonnell: Take me to Pitcairn - Full Documentary. Film report about a trip to Pitcairn. Joolzy Productions, 2009 (English).

Individual evidence

- ↑ Welcome to Pitcairn Islands Tourism - Pitcairn Stats. In: visitpitcairn.pn. Pitcairn Islands Tourism, accessed June 9, 2020 .

- ^ Robert A. Duncan, Ian McDougall , Robert M. Carter, Doug S. Coombs: Pitcairn Island - another Pacific hot spot? In: Nature . tape 251 , no. 5477 , October 25, 1974, p. 679-682 , doi : 10.1038 / 251679a0 (English).

- ↑ Pawala Valley Ridge, Pitcairn Iceland. In: peakbagger.com. Retrieved October 7, 2017 .

- ^ A b Naomi Kingston, Steve Waldren: The Plant Communities and Environmental Gradients of Pitcairn Island: The Significance of Invasive Species and the Need for Conservation Management . In: Annals of Botany . tape 92 , no. 1 , July 1, 2003, ISSN 0305-7364 , p. 31-40 , p. 32: Study area , doi : 10.1093 / aob / mcg106 (English).

- ^ Naomi Kingston, Steve Waldren: The Plant Communities and Environmental Gradients of Pitcairn Island: The Significance of Invasive Species and the Need for Conservation Management . In: Annals of Botany . tape 92 , no. 1 , July 1, 2003, ISSN 0305-7364 , p. 31-40 , p. 31: Abstract , doi : 10.1093 / aob / mcg106 (English).

- ^ Jacques Florence et al .: The flora of the Pitcairn Islands: a review . In: Biological Journal of the Linnean Society . tape 56 , no. 1-2 . Oxford University Press, September 1995, ISSN 0024-4066 , pp. 79-119 , p. 111: Aspidiaceae - Ctenitis cumingii Holttum , doi : 10.1111 / j.1095-8312.1995.tb01079.x (English).

- ^ Jacques Florence et al .: The flora of the Pitcairn Islands: a review . In: Biological Journal of the Linnean Society . tape 56 , no. 1-2 . Oxford University Press, September 1995, ISSN 0024-4066 , pp. 79-119 , p. 101: Asteraceae - Bidens mathewsii Sherff , doi : 10.1111 / j.1095-8312.1995.tb01079.x (English).

- ^ Herbert Ford: Pitcairn Island & Pacific Union College. The Pitcairn's First Voyage. Pitcairn Islands Stucy Center, accessed October 7, 2017 .

- ↑ Guillaume Molle, Aymeric Hermann: Pitcairn before the Mutineers: Revisiting the Isolation of a Polynesian Island . In: Sylvie Largeaud-Ortega (Ed.): The Bounty from the Beach. Cross-Cultural and Cross-Disciplinary Essays . ANU Press, Acton, Australia 2018, ISBN 978-1-76046-244-4 , chap. 2 , p. 67–94 , here pp. 71–74: The settlement of Pitcairn , doi : 10.22459 / BB.10.2018.02 (English).

- ↑ Guillaume Molle, Aymeric Hermann: Pitcairn before the Mutineers: Revisiting the Isolation of a Polynesian Island . In: Sylvie Largeaud-Ortega (Ed.): The Bounty from the Beach. Cross-Cultural and Cross-Disciplinary Essays . ANU Press, Acton, Australia 2018, ISBN 978-1-76046-244-4 , chap. 2 , p. 67–94 , here pp. 69–70: Traditional knowledge of the island , doi : 10.22459 / BB.10.2018.02 (English).

- ↑ Frederick William Beechey : Narrative of a voyage to the Pacific and Beering's strait, to co-operate with the polar expeditions: performed in His Majesty's ship Blossom, under the command of Captain FW Beechey, RN, FRS & c. in the years 1825, 26, 27, 28 . tape 1 . Henry Colburn and Richard Bentley, London 1831, Chapter IV, p. 96–136 , here p. 113 (English, full text ).

- ↑ Jacques-Antoine Moerenhout : Voyages aux îles du Grand Ocean . Tome premier. Arthus-Bertrand, Paris 1837, Chapitre Premier: Îles Pélagiennes - Section IV: Pitcaïrn, p. 33–84 , here p. 56 (French, full text of the 1959 reprint).

- ^ Katherine Routledge : The Mystery of Easter Island - The Story of an Expedition . 2nd Edition. Sifton, Praed & Co. Ltd., London 1920, Chapter XX: Pitcairn Island, p. 305-315 , here pp. 313-314 (English, full text ).

- ^ Andrew Howley: Pitcairn Islands Expedition: Remnants of a Lost Civilization. In: blog.nationalgeographic.org. National Geographic Society , March 30, 2012, accessed June 14, 2020 .

- ^ Henri Lavachery : Contribution à l'étude de l'archéologie de l'île de Pitcairn . In: Bulletin de la Société des Américanistes de Belgique . No. 19 . Brussels 1936, p. 3–42 (French).

- ^ Thor Heyerdahl , Edwin N. Ferdon: Reports of the Norwegian Archaeological Expedition to Easter Island and the East Pacific . tape 2 . London 1965, p. 3–7 (English).

- ^ Marshall I. Weisler: Henderson Island prehistory: colonization and extinction on a remote Polynesian island . In: Biological Journal of the Linnean Society . tape 56 , no. 1-2 , September 1995, ISSN 0024-4066 , pp. 377–404 , here p. 399–401: Long-distance Interaction , doi : 10.1111 / j.1095-8312.1995.tb01099.x (English).

- ↑ Guillaume Molle, Aymeric Hermann: Pitcairn before the Mutineers: Revisiting the Isolation of a Polynesian Island . In: Sylvie Largeaud-Ortega (Ed.): The Bounty from the Beach. Cross-Cultural and Cross-Disciplinary Essays . ANU Press, Acton, Australia 2018, ISBN 978-1-76046-244-4 , chap. 2 , p. 67–94 , here pp. 76–79: Exploitation of stone resources , doi : 10.22459 / BB.10.2018.02 (English).

- ↑ Guillaume Molle, Aymeric Hermann: Pitcairn before the Mutineers: Revisiting the Isolation of a Polynesian Island . In: Sylvie Largeaud-Ortega (Ed.): The Bounty from the Beach. Cross-Cultural and Cross-Disciplinary Essays . ANU Press, Acton, Australia 2018, ISBN 978-1-76046-244-4 , chap. 2 , p. 67–94 , here pp. 85–88: Tracing ancient inter-island mobility and exchange in south-east Polynesia , doi : 10.22459 / BB.10.2018.02 (English).

- ^ Marshal Weisler, Richard Walter: East Polynesian connectivity . In: Tamar Hodos et al. (Ed.): The Routledge Handbook of Archeology and Globalization . Routledge, Abingdon / New York 2017, ISBN 978-0-415-84130-6 , chap. 4.7, p. 369–386 , here pp. 376–379: The Mangareva-Pitcairn group: sustainability only with connectivity (English, limited preview in the Google book search).

- ↑ Guillaume Molle, Aymeric Hermann: Pitcairn before the Mutineers: Revisiting the Isolation of a Polynesian Island . In: Sylvie Largeaud-Ortega (Ed.): The Bounty from the Beach. Cross-Cultural and Cross-Disciplinary Essays . ANU Press, Acton, Australia 2018, ISBN 978-1-76046-244-4 , chap. 2 , p. 67–94 , here pp. 88–91: The abandonment of Pitcairn: Why, when and how? , doi : 10.22459 / BB.10.2018.02 (English).

- ^ Philip Carteret : An Account of a Voyage Round the World, in the Years MDCCLXVI, MDCCLXVII, MDCCLXVIII, and MDCCLXIX . In: John Hawkesworth (Ed.): An Account of the Voyages undertaken by the order of His Present Majesty for making Discoveries in the Southern Hemisphere . Vol. I. William Strahan and Thomas Cadell, London 1773, Chap. III. The Passage from Masafuero to Queen Charlotte's Islands; several Mistakes corrected concerning Davis's Land, and an Account of some small Islands, supposed to be the same that were seen by Quiros , S. 557-568 , here p. 561 (English, full text ).

- ↑ Caroline Alexander: The Bounty. The real story of the mutiny on the Bounty . Berlin Verlag, Berlin 2004, ISBN 3-8270-0163-3 , pp. 481 .

- ↑ Caroline Alexander: The Bounty. The real story of the mutiny on the Bounty . Berlin Verlag, Berlin 2004, ISBN 3-8270-0163-3 , pp. 442-447 .

- ^ History of Pitcairn Island. A Dictator Steps in 1832. In: Pitcairn Islands Study Center. Pacific Union College, accessed October 7, 2017 .

- ^ Robert W. Kirk: Paradise Past: The Transformation of the South Pacific, 1520-1920 . McFarland & Company, Jefferson, NC / London 2012, ISBN 978-0-7864-6978-9 , "The Mussolini of Pitcairn Island", pp. 63–64 (English, limited preview in Google Book Search).

- ^ Herbert Ford: Pitcairn Island as a port of call: a record, 1790-2010 . 2nd Edition. McFarland & Company, Jefferson, NC 2012, ISBN 978-0-7864-6604-7 , pp. 18 (English, limited preview in Google Book Search).

- ↑ a b Country profile: Pitcairn Islands (British Overseas Territory). Politics - Constitutional Status. In: Travel & living abroad. Foreign and Commonwealth Office , archived from the original on November 12, 2009 ; accessed on October 7, 2017 (English).

- ↑ Pitcairn's Population , accessed April 17, 2020.

- ↑ Census Data Pitcairn Island Study Center, accessed April 17, 2020.

- ↑ Pitcairn's History , accessed April 17, 2020.

- ↑ The People of Pitcairn Island , accessed April 17, 2020.

- ↑ Volgens opgave USSD , accessed April 17, 2020.

- ↑ Pitcairn Islands People 2020 , accessed April 17, 2020.

- ^ Pitcairn Islands Tourism: Welcome to Pitcairn Islands Tourisme. Pitcairn Islands Tourism, January 16, 2020, accessed January 16, 2020 .

- ↑ Country profile: Pitcairn Islands (British Overseas Territory). Administration. In: Travel & living abroad. Foreign and Commonwealth Office , archived from the original on November 12, 2009 ; accessed on October 7, 2017 (English).

- ^ Rob Solomon, Kirsty Burnett: Pitcairn Island Economic Review - Final Report. (PDF; 1.09 MB) Table 6: Estimates of annual household earnings. Pitcairn Islands Office, January 2014, p. 45 , accessed October 7, 2017 .

- ^ Pitcairn Island Pure Honey. In: Pitcairn Islands Products. Pitcairn Islands Office, accessed October 7, 2017 .

- ^ Rob Solomon, Kirsty Burnett: Pitcairn Island Economic Review - Final Report. (PDF; 1.09 MB) IV. Pitcairn Economic Development Potential - E. Apiculture. Pitcairn Islands Office, January 2014, pp. 32–33 , accessed October 7, 2017 .

- ^ Rob Solomon, Kirsty Burnett: Pitcairn Island Economic Review - Final Report. (PDF; 1.09 MB) IV. Pitcairn Economic Development Potential - B. Tourism. Pitcairn Islands Office, January 2014, pp. 25-28 , accessed October 7, 2017 .

- ^ Rob Solomon, Kirsty Burnett: Pitcairn Island Economic Review - Final Report. (PDF; 1.09 MB) III. Fiscal Situation - A. Investment Fund. Pitcairn Islands Office, January 2014, pp. 11–12 , accessed October 7, 2017 .

- ^ Pitcairn Single Programming Document - 10th European Development Fund. (PDF; 336 kB) European Cooperation Office , p. 10 , accessed on October 7, 2017 (English).

- ^ Rob Solomon, Kirsty Burnett: Pitcairn Island Economic Review - Final Report. (PDF; 1.09 MB) III. Fiscal Situation - C. Government Revenue - Stamp revenue. Pitcairn Islands Office, January 2014, pp. 14–15 , accessed October 7, 2017 .

- ^ Rob Solomon, Kirsty Burnett: Pitcairn Island Economic Review - Final Report. (PDF; 1.09 MB) Attachment 3: Fiscal Tables. Pitcairn Islands Office, January 2014, accessed October 7, 2017 .

- ↑ Summarized Accounts for 31 March 2016. (PDF; 430 kB) Pitcairn Islands Office, accessed on October 7, 2017 (English).

- ^ Daniel Martin: UK aid wasted on South Pacific windfarm fiasco: failed green energy scheme for only 55 people cost £ 250,000. In: MailOnline . Daily Mail and General Trust, April 7, 2013, accessed October 7, 2017.

- ^ Claymore II. In: shipstamps.co.uk. October 13, 2011, accessed October 7, 2017 .

- ↑ Minutes of the Public Meeting held at the Public Hall Commencting at 11amThursday 30th March 2017 Pitcairn Island Council, April 20, 2017.

- ^ Herbert Ford: Pitcairn Island as a Port of Call: A Record, 1790-2010 . 2nd edition 2014. McFarland, Jefferson 2012, ISBN 978-0-7864-6604-7 , pp. 6 .

- ^ Karsten Friedrich: A New Harbor for Pitcairn Island in 2015. In: Blogspot.com. January 2015, accessed on September 29, 2019 .

- ^ Pitcairn Island Immigration FAQ. The Government of the Pitcairn Islands. Retrieved March 27, 2019.

- ^ Assisting the UK's Overseas Territories: Child Sex Abuse on Pitcairn. In: About the FCO - FCO in Action. Foreign and Commonwealth Office , archived from the original on October 1, 2007 ; accessed on October 7, 2017 (English).

- ↑ Kathy Marks: Island slowly shrugs off infamy. In: The New Zealand Herald . January 24, 2011, archived from the original on September 5, 2012 ; accessed on October 7, 2017 (English).

- ^ Entry requirements - Pitcairn Island travel advice. Traveling with children. In: Foreign travel advice. Government of the United Kingdom, accessed October 7, 2017 .

- ↑ Mark Twain: The Great Revolution In Pitcairn . In: The Atlantic Monthly . Vol. XLIII, no. 255 , March 1879, p. 295–302 (English, online at UNZ.org).